Abstract

Eleven withanolides including six previously undescribed compounds, 16β-hydroxyixocarpanolide, 24,25-dihydroexodeconolide C, 16,17-dehydro-24-epi-dioscorolide A, 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A, 16-deoxyphiladelphicalactone C, and 4-deoxyixocarpalactone A were isolated from aeroponically grown Physalis philadelphica. Structures of these withanolides were elucidated by the analysis of their spectroscopic (HRMS, 1D and 2D NMR, ECD) data and comparison with published data for related withanolides. Cytotoxic activity of all isolated compounds was evaluated against a panel of five human tumor cell lines (LNCaP, ACHN, UO-31, M14 and SK-MEL-28), and normal (HFF) cells. Of these, 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A, withaphysacarpin, philadelphicalactone C, and ixocarpalactone A exhibited cytotoxicity against ACHN, UO-31, M14 and SK-MEL-28, but showed no toxicity to HFF cells.

Keywords: Physalis philadelphica, Solanaceae Aeroponic, cultivation Chemical, investigation, Withanolides, Cytotoxic activity

1. Introduction

The genus Physalis (Solanaceae) contains over 75 species some of which are used as foods and medicines (Whitson and Manos, 2005; Kindscher et al., 2012). Of these, the most widely distributed and cultivated species is Physalis philadelphica Lam. (Solanaceae) also known as tomatillo (Wang et al., 2012). Tomatillo is one of the basic ingredients of fresh and cooked Mexican and Central American green sauces. In South American traditional medicine, the fruits of P. philadelphica are used to relieve fever, cough, and amygdalitis, the leaves as a remedy for gastrointestinal disorders, and the calices for the treatment of diabetes (Maldonado et al., 2011). Plants of the genus Physalis have also received considerable attention because of their constituent withanolides, a class of polyoxygenated steroids based on C28 ergostane skeleton (Glotter, 1991). Withanolides, which also occur in other genera of Solanaceae including Acnistus, Datura, Dunalis, Jaborosa, and Withania are classified into two main classes, one containing the parent skeleton of withaferin A (group I) and the other with a modified skeleton (group II) (Yang et al., 2016). Many withanolides belonging to group I contain a 2,3-enone moiety in ring A and a δ-lactone moiety in their side chains. Based on their oxygenation patterns and the orientation of the side chain, group I withanolides belong to four basic classes to include withaferin A, withanolide A, withanolide D, withanolide E and their structural analogues. Among these, only those of withanolide E class contain an α oriented side chain and a β-hydroxy group at C-17 and are referred to as 17β-hydroxywithanolides.

Withanolides have been reported to exhibit a variety of biological activities including cytotoxic, anti-feedant, insecticidal, trypanocidal, leishmanicidal, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, phytotoxic, cholinesterase inhibitory and immune-regulatory activities, and effects on neurite outgrowth and synaptic reconstruction (Chen et al., 2011). Among these, the most widely investigated are cytotoxic and other activities related to their potential use as anticancer agents. These studies have suggested that unlike the most extensively investigated withanolide, withaferin A, withanolides belonging to withanolide E (13) class (17β-hydroxywithanolides) were selectively cytotoxic to only certain cancer cell lines and that these two classes of withanolides may have different molecular targets (Xu et al., 2015, 2017; Tewary et al., 2017). Thus, it was of interest to investigate the cytotoxic activity of withanolides belonging to different structural types.

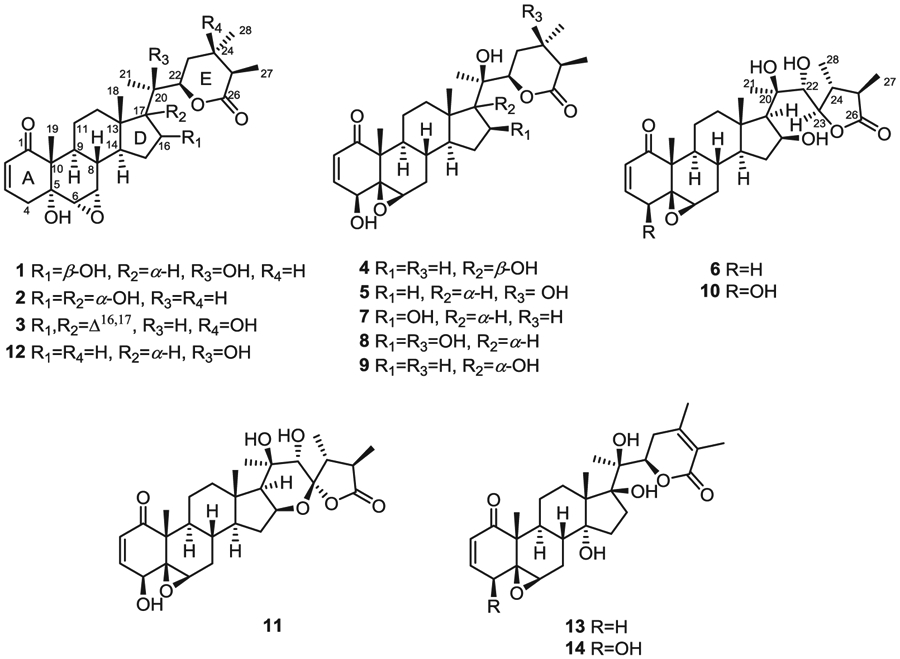

Previous phytochemical investigations of P. philadelphica, also known as P. ixocarpa Brot. (Hudson, 1986), have resulted in the isolation of several withanolides, including physalin B (Subramanian and Sethi, 1973), withaphysacarpin (Subramanian and Sethi, 1973; Kennelly et al., 1997; Su et al., 2002), ixocarpalactone A (Kirson et al., 1979; Su et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2003; Maldonado et al., 2011), ixocarpalactone B (Kirson et al., 1979; Su et al., 2002), ixocarpanolide (Abdullaev et al., 1986; Maldonado et al., 2011), 2,3-dihydro-3-methoxywithaphysacarpin and 24,25-dihydrowithanolide D (Kennelly et al., 1997), philadelphicalactone A (Su et al., 2002; Maldonado et al., 2011), philadelphicalactone B, 18-hydroxywithanolide D and withanone (Su et al., 2002), philadelphicalactone C (Maldonado et al., 2011), philadelphicalactone D (Maldonado et al., 2011), 2,3-dihydro-3β-methoxyisocarpalactone A (Gu et al., 2003), 2,3-dihydro-3β-methoxyisocarpalactone B and 4β,7β,20R-trihydroxy-1-oxowitha-2,5-dien-22,26-olide (Gu et al., 2003). In our continuing interest on new and/or biologically active withanolides (Wijeratne et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015, 2016, and 2017), we have investigated aeroponically grown P. philadelphica and herein we report the isolation, identification, and cytotoxic activity of six new and five known withanolides, some of which have not been encountered in wild-crafted plants. The new withanolides were identified as 16β-hydroxyixocarpanolide (1), 24,25-dihydroexodeconolide C (2), 16,17-dehydro-24-epi-dioscorolide A (3), 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A (4), 16-deoxyphiladelphicalactone C (5), and 4-deoxyixocarpalactone A (6). Comparison of spectroscopic data with those reported led to the identification of the known withanolides as withaphysacarpin (7) (Kennelly et al., 1997; Su et al., 2002), philadelphicalactone A (8) (Su et al., 2002; Maldonado et al., 2011), philadelphicalactone C (9) (Maldonado et al., 2011), and ixocarpalactones A (10) and B (11) (Kirson et al., 1979; Su et al., 2002).

2. Results and discussion

The aerial parts of aeroponically grown P. philadelphica were extracted with methanol and the resulting extract was fractionated by solvent-solvent partitioning with hexanes and 80% aq. methanol followed by 50% aq. methanol and chloroform to obtain hexanes, 50% aq. methanol and chloroform fractions. Of these only the chloroform fraction was found to contain withanolides. Thus, the chloroform fraction was further fractionated by silica gel and reversed phase column chromatography followed by preparative HPLC to afford withanolides 1–11 (see Fig. 1) as white amorphous powders.

Fig. 1.

Structures of withanolides 1–11 from aeroponically grown P. philadelphica, ixocarpanolide (12), withanolide E (13), and 4β-hydroxywithanolide E (14).

2.1. Structure elucidation of the new withanolides 1–6

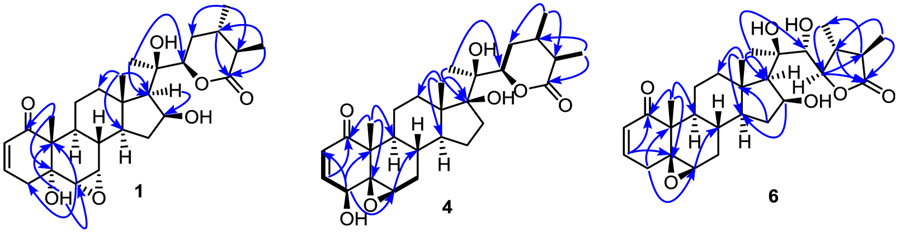

The 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of withanolides 1–3 (Tables 1 and 2) suggested that these are structurally related to each other and contain a carbon skeleton bearing 2,3-enone, 5α-hydroxy, 6α,7α-epoxy moieties in rings A/B and δ lactone moiety in the side chain similar to ixocarpanolide (12) (Abdullaev et al., 1986). Withanolide 1 possessed a molecular formula of C28H40O7 as determined by its HRMS and NMR data and indicated nine degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (Table 1) displayed signals due to three methyl groups attached to non-protonated carbons [δH 1.18 (3H, s, H3-19)], 1.19 (3H, s, H3-18), and 1.32 (3H, s, H3-21)], two methyl groups on protonated carbons [δH 1.14 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-28) and 1.23 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-27)], two vicinal protons of an epoxide moiety [δH 3.04 (1H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, H-6β), 3.31 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 4.0 Hz, H-7β)], two overlapping oxygenated methines [δH 4.61 (2H, m, H-16 and H-22)], and two vicinal vinyl protons [δH 5.83 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 10.0 Hz, H-2), 6.58 (1H, ddd, J = 2.0, 5.2, 10.0 Hz, H-3)]. Its 13C NMR spectrum (Table 2) exhibited 28 signals corresponding to five methyls (δC 14.2, 14.7, 14.8, 21.1, and 22.3), 2,3-enone moiety [δC 129.0 (C-2), 139.7 (C-3), 203.1 (C-1)], two oxygenated methines [δC 73.4 (C-16) and 81.2 (C-22)], two oxygenated carbons of an epoxide moiety [δC 56.3 (C-6) and 57.1 (C-7)], two oxygenated tetrasubstituted carbons [δC 73.2 (C-5) and 78.4 (C-20)], and a carbonyl carbon of a δ lactone [δC 175.9 (C-26)]. The presence of the 5α-hydroxy-6α,7α-epoxy moiety in rings A and B of 1 was inferred from the characteristic methine resonances at δC 56.3 (C-6) and 57.1 (C-7), and that due to oxygenated carbon at δC 73.2 (C-5) (Yu et al., 2017). The planar structure of 1 was established by the analysis of its HMBC spectrum which showed key correlations for H3-19/C-1, H3-19/C-5, H-6/C-4 (δC 36.7), and H-6/C-10 (δC 51.0) for the A/B ring system, H3-18/C-14 (δC 49.6), H3-18/C-17 ((δC 58.3), H3-18/C-12 (δC 40.6), H-17/C-16, and H3-21/C-17 for the C/D ring system, H3-27/C-26, H3-28/C-23 (δC 31.3), and H3-21/C-22 for the ring E (Fig. 2). The NOESY correlations (Fig. 3) of H3-19/H-4β [δH 2.68 (brd, J = 18.8 Hz)], H3-19/H-8β (δH 1.84, m), H-4α [δH 2.52 (dd, J = 5.2, 18.8 Hz)]/H-6β, H-6β/H-7β, and H-7β/H-8β confirmed the orientation of the 6,7-epoxide group as α. The orientations of H-14, OH-16 and H-17 were confirmed to be α, β, and α respectively, by the NOESY correlations of H-7β/H-15α [δH 2.42 (dt, J = 12.4, 7.6 Hz)], H-15α/H-16α, H-16α/H-14α (δH 1.23, m), H-16α/H-17α (δH 1.28, m), and H3-21/H-12β (δH 2.13, m). The ECD spectrum of 1 exhibited a negative Cotton effect at 335 nm confirming the configuration and the trans-linkage of A and B rings (Begley et al., 1976), and a positive Cotton effect at 242 nm confirming the R configuration of C-22 (Abdullaev et al., 1986). Almost the same 13C NMR chemical shifts observed for C-20 and the carbons of D and E rings of 1 and withaphysacarpin (7) (Kennelly et al., 1997), also encountered in this work, suggested that the configuration of C-20 of 1 is the same as that of 7. Thus, the structure of 1 was elucidated as 16β-hydroxyixocarpanolide [(20R,22R,24S,25R)-5α,16β,20-trihydroxy-6α,7α-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2-enolide].

Table 1.

1H NMR (400 MHz) spectroscopic data for withanolides 1–6 (CDCl3, δ in ppm, J in Hz).a

| Position | 1 | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5b | 6b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 5.83 dd (2.4, 10.0) | 5.78 dd (2.0, 10.0) | 5.83 dd (2.0, 10.0) | 6.16 d (10.0) | 6.11 d (10.0) | 5.97 dd (2.8, 10.0) |

| 3 | 6.58 ddd (2.0, 5.2, 10.0) | 6.54 ddd (2.0, 4.8, 10.0) | 6.57 ddd (2.0, 4.8, 10.0) | 6.89 dd (2.0, 10.0) | 6.89 dd (2.4, 10.0) | 6.80 ddd (2.0, 6.0, 10.0) |

| 4 α | 2.52 dd (5.2, 18.8) | 2.46 dd (4.8, 19.0) | 2.51 m | 3.70 dd (2.0, 5.6) | 3.59 dd (2.4, 5.6) | 1.85 dd (6.0, 18.8) |

| β | 2.68 brd (18.8) | 2.62 dt (19.0, 2.0) | 2.67 brd (18.8) | 2.93 brd (18.8) | ||

| 6 | 3.04 d (4.0) | 2.98 d (3.6) | 3.02 d (3.6) | 3.18 brs | 3.10 brs | 3.08 d (2.4) |

| 7 | 3.31 dd (2.0, 4.0) | 3.19 dd (2.0, 3.6) | 3.36, dd (2.0, 3.6) | 1.25 m | 1.18 m | 1.18 m |

| 2.15 ddd (2.4, 3.6, 14.8) | 2.06 ddd (2.4, 3.6, 14.8) | 1.99 m | ||||

| 8 | 1.84 m | 1.64 m | 1.94 m | 1.58 m | 1.40 m | 1.62 m |

| 9 | 1.54 m | 1.52 dt (3.2, 11.8) | 1.65 dt (3.2, 10.4) | 0.95 m | 0.79 m | 1.06 m |

| 11 | 1.37 m | 1.18 m | 1.40 m | 1.45 m | 1.37 m | 1.48 m |

| 2.74 ddd (3.6, 7.4, 13.2) | 2.67 ddd (3.6, 6.8, 13.2) | 2.85 ddd (3.2, 6.8, 13.2) | 1.81 m | 1.62 m | 1.99 m | |

| 12 | 1.28 m | 1.63 m | 1.49 m | 1.65 m | 1.07 m | 1.15 m |

| 2.13 m | 1.77 m | 1.72 m | 1.89 m | 1.88 m | 2.05 m | |

| 14 | 1.23 m | 2.13 m | 1.73 m | 1.52 m | 1.45 m | 0.72 m |

| 15 | 1.55 m | 1.63 m | 2.03 m | 1.36 m | 1.08 m | 1.28 m |

| 2.42 dt (12.4, 7.6) | 1.80 m | 2.28 ddd (14.6, 6.4, 3.2) | 1.62 m | 1.57 m | 2.16 m | |

| 16 | 4.61 m | 4.24 brd (7.6) | 5.51 brs | 1.66 m | 1.49 m | 4.39 m |

| 2.05 m | 1.83 m | |||||

| 17 | 1.28 m | 0.86 m | 1.27 m | |||

| 18 | 1.19 s | 0.79 s | 0.85 s | 0.87 s | 0.73 s | 1.09 s |

| 19 | 1.18 s | 1.11 s | 1.19 s | 1.37 s | 1.31 s | 1.20 s |

| 20 | 2.11 m | 2.45 dq (7.2, 6.0) | ||||

| 21 | 1.32 s | 0.96 d (7.2) | 1.08 d (7.2) | 1.25 s | 1.13 s | 1.28 s |

| 22 | 4.61 m | 4.62 ddd (3.2, 4.0, 10.8) | 4.29 ddd (4.1, 6.0, 11.6) | 4.64 brd (8.8) | 4.02 dd (5.2, 11.2) | 3.94 brs |

| 23 | 1.54 m | 1.63 m | 1.92 dd (11.6, 14.6) | 1.65 m | 1.75–1.85 m | 4.41 m |

| 1.98 m | 1.85 m | 2.05 dd (4.1, 14.6) | 2.03 m | |||

| 24 | 1.83 m | 1.62 m | 1.71 m | 2.23 m | ||

| 25 | 2.22 dq (9.6, 6.8) | 2.15 m | 2.55 q (7.2) | 2.12 m | 2.40 q (6.8) | 2.62 m |

| 27 | 1.23 d (6.8) | 1.15 d (6.8) | 1.24 d (7.2) | 1.17 d (6.8) | 1.12 d (6.8) | 1.11 d (6.8) |

| 28 | 1.14 d (6.8) | 1.07 d (7.2) | 1.38 s | 1.08 d (6.8) | 1.26 s | 1.17 d (6.8) |

Assignments based on 1H-1H-COSY, HSQC, HMBC and NOESY data.

CDCl3/CD3OD (100:1) was used as solvent.

Table 2.

13C NMR (100 MHz) spectroscopic data for withanolides 1–6 and 9 (CDCl3, δ in ppm).a

| Position | 1 | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5b | 6b | 9b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 203.1, C | 203.6, C | 203.1, C | 202.1, C | 202.5, C | 203.6, C | 202.2, C |

| 2 | 129.0, CH | 128.8, CH | 129.1, CH | 132.4, CH | 132.3, CH | 129.2, CH | 132.4, CH |

| 3 | 139.7, CH | 139.9, CH | 139.5, CH | 141.9, CH | 142.7, CH | 144.5, CH | 142.5, CH |

| 4 | 36.7, CH2 | 36.6, CH2 | 36.7, CH2 | 69.8, CH | 69.7, CH | 32.8, CH2 | 69.8, CH |

| 5 | 73.2, C | 73.2, C | 73.4, C | 63.9, C | 63.8, C | 62.1, C | 63.9, C |

| 6 | 56.3, CH | 56.1, CH | 56.0, CH | 62.1, CH | 61.1, CH | 63.2, CH | 61.3, CH |

| 7 | 57.1, CH | 56.9, CH | 57.4, CH | 31.2, CH2 | 30.9, CH2 | 30.9, CH2 | 31.0, CH2 |

| 8 | 34.7, CH | 35.5, CH | 34.5, CH | 30.6, CH | 29.1, CH | 28.9, CH | 29.4, CH |

| 9 | 35.6, CH | 34.9, CH | 36.1, CH | 43.6, CH | 43.9, CH | 44.6, CH | 43.4, CH |

| 10 | 51.0, C | 50.9, C | 51.2, C | 47.7, C | 47.7, C | 48.4, C | 47.7, C |

| 11 | 21.6, CH2 | 21.2, CH2 | 21.5, CH2 | 22.2, CH2 | 21.1, CH2 | 23.1, CH2 | 21.0, CH2 |

| 12 | 40.6, CH2 | 32.9, CH2 | 34.6, CH2 | 33.4, CH2 | 39.3, CH2 | 40.1, CH2 | 31.7, CH2 |

| 13 | 44.,1 C | 49.3, C | 47.7, C | 50.0, C | 42.4, C | 43.1, C | 46.9, C |

| 14 | 49.6, CH | 44.0, CH | 52.7, CH | 51.3, CH | 56.3, CH | 54.1, CH | 50.3, CH |

| 15 | 36.2, CH2 | 34.7, CH2 | 30.6, CH2 | 25.1, CH2 | 23.6, CH2 | 36.9, CH2 | 22.8, CH2 |

| 16 | 73.4, CH | 75.2, CH | 123.6, CH | 34.8, CH2 | 21.8, CH2 | 72.9, CH | 31.8, CH2 |

| 17 | 58.3, CH | 82.3, C | 155.6, C | 87.4, C | 54.4, CH | 57.5, CH | 89.9, C |

| 18 | 14.8, CH3 | 14.8, CH3 | 16.5, CH3 | 16.7, CH3 | 13.3, CH3 | 14.6, CH3 | 15.8, CH3 |

| 19 | 14.7, CH3 | 14.6, CH3 | 14.9, CH3 | 17.2, CH3 | 16.5, CH3 | 14.9, CH3 | 16.5, CH3 |

| 20 | 78.4, C | 42.8, CH | 36.3, CH | 78.9, C | 74.9, C | 79.1, C | 75.7, C |

| 21 | 22.3, CH3 | 9.6, CH3 | 17.2, CH3 | 19.9, CH3 | 19.7, CH3 | 22.2, CH3 | 22.0, CH3 |

| 22 | 81.2, CH | 77.3, CH | 77.3, CH | 81.0, CH | 79.8, CH | 72.9, CH | 80.8, C |

| 23 | 31.3, CH2 | 32.7, CH2 | 41.6, CH2 | 31.8, CH2 | 39.2, CH2 | 78.4, CH | 30.0, CH2 |

| 24 | 31.1, CH | 31.2, CH | 71.0, C | 31.2, CH | 70.1, C | 41.7, CH | 30.7, CH |

| 25 | 40.7, CH | 40.5, CH | 44.9, CH | 40.4, CH | 44.9, CH | 40.0, CH | 40.2, CH |

| 26 | 175.9, C | 177.2, C | 174.1, C | 175.1, C | 175.3, C | 180.9, C | 175.1, C |

| 27 | 14.2, CH3 | 14.1, CH3 | 8.8, CH3 | 14.1, CH3 | 8.4, CH3 | 14.0, CH3 | 13.8, CH3 |

| 28 | 21.1, CH3 | 20.8, CH3 | 29.0, CH3 | 21.0, CH3 | 28.2, CH3 | 12.9, CH3 | 20.8, CH3 |

Assignments based on DEPT, HSQC and HMBC data.

CDCl3/CD3OD (100:1) was used as solvent.

Fig. 2.

Key HMBC (→) correlations of withanolides 1, 4, and 6 and key 1H–1H COSY (−) correlations of 4.

Fig. 3.

Key NOESY correlations of withanolides 1, 4, and 6.

The HRMS and NMR data of withanolide 2 indicated that it has the same molecular formula (C28H40O7) as that of 1. Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 1 and 2 suggested that they had closely related structures and contained the 2,3-enone, OH-5α, 6α,7α-epoxide and ring E δ lactone moieties. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 (Table 1) analyzed with the help of 1H–1H COSY data displayed three CH3–CH moieties instead of two in 1, suggesting that C-20 in 2 is a methine carbon. Analysis of the HMBC spectrum of 2 (see Figs. S9 and S35, Supplementary data) revealed that both H3-21 [δH 0.96 (3H, d, J = 7.2 Hz)] and H3-18 [δH 0.79 (3H, s)] showed correlations with an oxygenated tetrasubstituted carbon at δ 82.3, suggesting that C-17 is oxygenated. The presence of OH-16 in 2 was deduced from the HMBC correlations of H-16 [δH 4.24 (1H, brd, 7.6 Hz)]/C-14 (δC 44.0) and H-16/C-20 (δC 42.8). The α orientations of OH-16 and OH-17 were determined by the NOESY correlations of H3-18/H-20 and H3-18/H-16. The ECD spectrum of 2 exhibited a negative Cotton effect at 336 nm confirming the configuration and the trans-linkage of A and B rings (Begley et al., 1976), and a positive Cotton effect at 242 nm confirming the R configuration of C-22 (Abdullaev et al., 1986). Thus, withanolide 2 was identified as 24,25-dihydroexodeconolide C [(20S,22R,24S,25R)-5α,16α,17α-trihydroxy-6α,7α-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2-enolide].

The molecular formula of withanolide 3 was determined as C28H38O6 using a combination of HRMS and 13C NMR data and indicated ten degrees of unsaturation. Analysis of its 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data suggested that it contained 2,3-enone, OH-5α, 6α,7α-epoxide and ring E δ lactone moieties as in 1 and 2. However, proton splitting patterns and carbon chemical shifts of those belonging to rings D and E of 3 were found to be different from those of 1 and 2. A broad singlet proton signal at δH 5.51 suggested that 3 contained an additional double bond bearing an olefinic proton. This double bond in 3 was found to be at C-16(17) based on the HMBC correlations of H3-18 [δH 0.85 (3H, s)]/C-17 (δC 155.6), H3-21 [δH 1.08 (3H, d, J = 7.2 Hz)]/C-17, H-16/C-13 (δC 47.7), and H-16/C-14 (δC 52.7) (see Figs. S15 and S35, Supplementary data). Among the five methyl proton signals in the 1H NMR spectrum of 3, three appeared as singlets (δH 1.38, 1.19, and 0.85) and two as doublets [δH 1.24 (d, J = 7.2 Hz) and 1.08 (d, J = 7.2 Hz)] suggesting that either C-24 or C-25 should be hydroxylated. The attachment of OH to C-24 was established by the HMBC correlations of H3-27 [δH 1.24 (3H, d, J = 7.2 Hz)]/C-26 (δC 174.1), H3-27/C-24 (δC 71.0), and H-22 [δH 4.29 (1H, m)]/C-24. The orientation of the methyl groups at C-24 and C-25 were found to be same (α and α, respectively) as those in 1 and 2, by the NOESY correlations of H3-28/H-22α and H3-28/H-25 [δH 2.55 (1H, m)] (see Figs. S17 and S35, Supplementary data). Similar to 1 and 2, the ECD spectrum of 3 exhibited a negative Cotton effect at 336 nm confirming the configuration and the trans-linkage of A and B rings (Begley et al., 1976), and a positive Cotton effect at 242 nm confirming the R configuration of C-22 (Abdullaev et al., 1986). Accordingly, withanolide 3 was identified as 16,17-dehydro-24-epi-dioscorolide A [(20S,22R,24R,25R)-5α,24-dihydroxy-6α,7α-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2,16-dienolide].

The HRMS and NMR data of withanolide 4 were consistent with the molecular formula C28H40O7 indicating nine degrees of unsaturation. Its 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1) exhibited typical resonances of withanolides belonging to the group I type (Yang et al., 2016) comprising of two olefinic protons [δH 6.89 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 10.0 Hz, H-3), 6.16 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz, H-2)], two oxygenated methines [δH 3.70 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 5.6 Hz, H-4), 4.64 (1H, brd, J = 8.8 Hz, H-22)], a proton of the 5β,6β-epoxide [δH 3.18 (1H, brs, H-6)], and five methyl groups [δH 0.87 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.37 (3H, s, H3-19), 1.25 (3H, s, H3-21), 1.17 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-27), 1.08 d (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-28)]. The 13C NMR data (Table 2) indicated the presence of 28 carbons including two carbonyls of 2,3-enone (δC 202.1, C-1) and δ-lactone (δC 175.1, C-26)] moieties, two oxygenated methines (δC 69.8, C-4; 81.0, C-22), two oxygenated tertiary carbons (δC 87.4, C-17; 78.9, C-20), oxygenated carbons of the 5β,6β-epoxide moiety (δC 63.9, C-5; 62.1, C-6), two quaternary carbons (δC 47.7, C-10; 50.0 C, C-13), together with five methylene and five methyl carbons. The HMBC data for 4 (Fig. 2) together with the above 1H and 13C NMR data suggested that its planar structure is the same as that of philadelphicalactone A (9) previously encountered in soil-grown P. philadelphica (Su et al., 2002) and also found to co-occur in this extract (see below). The orientations of OH-4 and 5,6-epoxide in 4 were shown to be β by the NOESY correlations of H3-19/OH-4 [δH 2.99 (1H, brs)] and H-4/H-6. The NOESY correlations of H3-18 [δH 0.87 (3H, s)]/OH-17 [δH 3.13 (1H, brs)] and H3-21 [δH 1.25 (3H, s)/H2-12 [δH 1.65 (1H, m) and 1.89 (1H, m)] suggested that OH-17 is β-oriented. The orientations of the methyl groups at C-24 and C-25 of ring E were found to be α and β respectively, similar to those of 1 and 2 and the known withanolides 7, 9, and 12 based on the NOESY correlations of H3-28 [δH 1.08 (d, J = 6.8 Hz)]/H-22α and H-22α/H-25. The ECD spectrum of 4 exhibited positive Cotton effects at 339 and 242 nm, indicating the configuration and the cis linkage of the A and B ring systems (Begley et al., 1976) and the R absolute configuration of C-22 (Abdullaev et al., 1986), respectively. The foregoing data suggested that 4 and 9 were identical to each other except for the orientation of OH-17. Since the structure of 9 has been confirmed by X-ray analysis and the orientation of OH-17 has been shown to be α (Su et al., 2002), OH-17 in 4 should be β oriented. Previous studies have demonstrated applicability of the 13C NMR γ-gauche effects on the chemical shifts of C-12, C-18, and C-21 to determine the orientation of OH-17 in a number of withanolides containing epimeric OH-17β and OH-17α groups including perulactone B (17β-OH) and perulactone H (17α-OH) (Fang et al., 2012), withanolide E (17β-OH) and 17-isowithanolide E (17α-OH) (Gottlieb and Kirson, 1981), and 17-epi-withanolide K (17β-OH) (Choudhary et al., 1995) and withanolide K (17α-OH) (Gottlieb and Kirson, 1981). The 13C NMR data for these isomeric pairs of 17-hydroxywithanolides have suggested that the change in orientation of OH-17 from β to α caused a decrease (up-field shift) in the chemical shifts of C-12 and C-18, and an increase (down-field shift) in the chemical shift of C-21 due to the γ-gauche effect. The chemical shift differences observed for 4 and 9 (Δ = δ9−δ4) were found to be −1.7 ppm for C-12, −0.9 ppm for C-18, and +2.1 ppm for C-21, further confirming the orientation of OH-17 in 4 to be β. Based on the foregoing evidence the structure of withanolide 4, named as 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A, was determined as (20R,22R,24S,25R)-4β,17β,20-trihydroxy-5β,6β-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2-enolide (4). To the best of our knowledge, this constitutes the first report of the occurrence of a 17β-hydroxywithanolide in P. philadelphica.

The molecular formula of withanolide 5 was determined as C28H40O7 by a combination of HRMS and 13C NMR data and indicated nine degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR data of 5 (Table 1) showed characteristic signals for H-2 [δH 6.11 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz)] and H-3 [δH 6.89 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 10.0 Hz)] of 2,3-enone, H-4 [δH 3.59 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 5.6 Hz)] of 4β-hydroxymethine, H-6β of 5β,6β-epoxide [δH 3.10 (1H, brs)], H-22 [δH 4.02 (1H, dd, J = 5.2, 11.2 Hz)], H3-18 [δH 0.73 (3H, s)], H3-19 [δH 1.31 (3H, s)], and H3-21 [δH 1.13 (3H, s)], in addition to the two methyl signals at δH 1.12 (3H, d, J = 6.8) and 1.26 (3H, s). These data suggested that one of the methyl groups in the δ lactone side chain of 5 is attached to a protonated carbon and the other to an oxygenated carbon. This oxygenated carbon was determined to be C-24 by the HMBC correlations of H3-27/C-24 (δC 70.1), H3-27/C-26 (δC 175.3), H3-28/C-25 (δC 44.9), and H3-28/C-23 (δC 39.2) (see Figs. S27 and S35, Supplementary data). The orientations of OH-4 and 5,6-epoxide moiety in 5 were determined to be β by NOESY correlations of H-6α/H2-7 [δH 1.18 (1H, m), 2.06 (1H, ddd, J = 2.4, 3.6, 14.8 Hz)], and H-6α/H-4α (see Fig. S29, Supplementary data). The orientation of the side chain was deduced to be β by the NOESY correlation of H3-18/H3-21. The NOESY correlations observed for H-22α/H3-28 and H3-28/H-25 [δH 2.40 (1H, q, J = 6.8 Hz)] suggested that CH3-27 is β oriented whereas CH3-28 is α oriented as in withanolides 1–4 found to co-occur in this extract. The ECD spectrum of 5 exhibited positive Cotton effects at 339 and 242 nm, confirming the configuration and the cis linkage of A and B rings (Begley et al., 1976) and the R absolute configuration of C-22 (Abdullaev et al., 1986), respectively. Thus, withanolide 5 was identified as 16-deoxyphiladelphicalactone C [(20R,22R,24R,25R)-4β,20,24-trihydroxy-5β,6β-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2-enolide].

The HRMS and NMR data of withanolide 6 were consistent with the molecular formula C28H40O7 and indicated nine degrees of unsaturation. The 1H NMR data of 6 (Table 1) exhibited resonances due to two olefinic protons [δH 6.80 (1H, ddd, J = 2.0, 6.0,10.0 Hz, H-3), 5.97 (1H, dd, J = 2.8, 10.0 Hz, H-2)], three oxygenated methines [δH 4.39 (1H, m, H-16), 4.41 (1H, m, H-23), 3.94 (1H, brs, H-22)], and five methyls [δH 1.09 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.20 (3H, s, H3-19), 1.28 (3H, s, H3-21), 1.11 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-27), 1.17 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz, H3-28)]. The 13C NMR spectrum of 6 (Table 2), assigned with the help of HSQC data, supported the presence of 2,3-enone (δC 203.6, C-1; 129.2 C-2; 144.5, C-3), 5β,6β-epoxide (δC 62.1, C-5; 63.2, C-6), and lactone carbonyl (δC 180.9) moieties similar to ixocarpalactone A (10) (Su et al., 2002) with a ring E γ-lactone side chain moiety. Comparison of the NMR data of 6 with those of 10 and the analysis of its HMBC data (Fig. 2) indicated that the CHOH-4 in 10 was replaced by a CH2-4 in 6. The orientation of the 5,6-epoxide of 6 was confirmed by 1D NOESY correlations of H3-18/H-4β and H-4α/H-6α (Fig. 3). The orientation of the side chain in 6 was found to be β as in 10 by the NOESY correlations of H-23/H3-28 and H3-28/H-25 [δH 2.62 (1H, m)]. A positive Cotton effect at 361 nm in the ECD spectrum of 6 confirmed the configuration and cis-linkage of A and B rings (Begley et al., 1976). Based on the foregoing evidence, the structure of withanolide 6 was determined as 4-deoxyixocarpalactone A [(20R,22R,23R,24R,25R)-16β,20,22-trihydroxy-5β,6β-epoxy-1-oxowitha-2-en-23,26-olide].

2.2. Cytotoxic activities of withanolides

Previous studies by us and others have shown interesting cytotoxic activity for a number of withanolides, some exhibiting selectivity for certain cancer cell lines (Chen et al., 2011; Maldonado et al., 2011; Wijeratne et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015, 2016 and 2017). Most noteworthy is the potency and selectivity shown by some 17β-hydroxywithanolides against prostate cancer cell lines, LNCaP and PC-3 (Xu et al., 2015). Withanolides 1–11 encountered in this study were evaluated for their cytotoxic activity in a panel of five selected tumor cell lines consisting of LNCaP (androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma), ACHN (human renal adenocarcinoma), UO-31 (human kidney carcinoma), M14 (human melanoma), SK-MEL-28 (human melanoma), and normal HFF (human foreskin fibroblast) cells. Withanolide E (13) and 4β-hydroxywithanolide E (14), the 17β-hydroxywithanolides which we have previously shown to exhibit selective and potent activity for LNCaP cells (Xu et al., 2017), were included for comparison purposes. The IC50 data for the active withanolides are presented in Table 3. Of those tested, withanolides 4, 7, 9, and 10 showed selective cytotoxicity against human renal and kidney carcinoma, and melanoma cell lines compared to normal HFF cells. It is noteworthy that all active withanolides contain 2,3-enone and 5β,6β-epoxide moieties in rings A and B. However, ixocarpalactone B (11) with these moieties had no cytotoxic activity up to concentration of 10.0 μM suggesting the importance of side chain structure for this activity. The lack of activity of the 17β-hydroxywithanolide, 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A (4), for LNCaP cells up to a concentration of 2.0 μM compared to its analogue 14 (IC50 0.16 ± 0.40), with 24,25-ene moiety and OH-14α further supports our previous finding that the reduction of the 24,25-double bond of the side chain and/or absence of OH-14α lead to a decrease in cytotoxic activity (Xu et al., 2017).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity data for withanolides 4, 7, 9 and 10 from aeroponically cultivated P. philadelphica, withanolide E (13) and 4β-hydroxywithanolide E (14) against a panel of selected tumor cell lines and normal cells.a

| Compound | Cell linesb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNCaP | ACHN | UO-31 | M14 | SK-MEL-28 | HFF | |

| 4 | >2.0 | 6.9 ± 0.0 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | >10.0 | >10.0 | >10.0 |

| 7 | >2.0 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | >10.0 |

| 9 | >2.0 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | >10.0 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | >10.0 |

| 10 | >2.0 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.4 | >10.0 |

| 13 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | NT | >2.0 | >2.0 | >10.0 |

| 14 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | >2.0 | NT | >2.0 | >2.0 | >10.0 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | NT | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

Results are expressed as IC50 values in μM. Doxorubicin and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls. Withaferin A (13) and withanolide E (14) were used for comparison purposes. NT = not tested. Withanolides 1–3, 5–6, 8, and 11 had no activity up to 10 μM.

Key: ACHN = human renal adenocarcinoma; UO-31 = human kidney carcinoma; M14 = human melanoma; SK-MEL-28 = human melanoma; HFF = human foreskin fibroblast.

3. Conclusions

Chemical investigation of aeroponically grown P. philadelphica led to the isolation of six new and five known withanolides further demonstrating the applicability of this environmentally-controlled cultivation technique for their efficient production. One of the new natural products encountered, 17-epi-philadelphicalactone A (4), belongs to 17β-hydroxywithanolide group of withanolides known to have potent and selective cytotoxicity to certain cancer cell lines and it is significant that this is the first report of the occurrence of this group of withanolides in P. philadelphica. When evaluated for cytotoxic activity, withanolides 4, 7, 9, and 10 exhibited selective cytotoxicity against human renal carcinoma (ACHN), kidney carcinoma (UO-31), and melanoma (M14 and SK-MEL-28) cell lines compared to normal human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells. These findings provide additional support that investigation of withanolide producing plants and application of aeroponic technique for their cultivation may lead to the discovery of new withanolide analogues with potent and selective cytotoxicity to some tumor cell lines.

4. Experimental

4.1. General experimental procedures

Optical rotations were measured at 25 °C with a JASCO Dip-370 digital polarimeter using MeOH as solvent. UV spectra were recorded in MeOH using a Shimadzu UV-1601 UV–Vis spectrometer. ECD spectra were recorded in MeOH on a Jasco 810 spectrometer at 25 °C, using a quartz cell with 1.0 mm optical path length. The 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 NMR instrument at 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz for 13C NMR. Chemical shift values (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm), and the coupling constants are in Hz. Low-resolution and high-resolution MS were recorded on Shimadzu LCMS-QP8000α and Agilent G6224A TOF mass spectrometers, respectively. Normal phase column chromatography was performed using Baker silica gel 40 μm flash chromatography packing (J.T. Baker) and reversed phase chromatography was carried out using BAKERBOND C18 40 μm preparative LC packing (J.T. Baker). Analytical and preparative thin-layer chromatography (TLC) were performed on pre-coated plates (0.20 mm thickness) of silica gel 60 F254 (Merck) and RP-18 F254S (Merck). The HPLC purifications were carried out on a Phenomenex Luna 5 μm C18 column (10 × 250 mm) with a Waters Delta Prep system consisting of a PDA 996 detector. The MM2 energy minimizations of possible conformations of compounds were performed using Chem3D 15.0 from PerkinElmer Inc.

4.2. Aeroponic cultivation and harvesting of P. philadelphica

The seeds of Physalis philadelphica Lam. (Solanaceae) obtained from Trade Wind Fruit (P.O. Box 1102, Windsor, CA 95492) were germinated in 1.0 inch Grodan rock-wool cubes in a Barnstead LabLine growth chamber kept at 28 °C with 16 h of fluorescent lighting and 25–50% humidity. After ca. 4 weeks in the growth chamber, seedlings with an aerial length of ca. 5.0 cm were transplanted to aeroponic cultivation boxes in green houses at the University of Arizona Natural Products Center, 250 E. Valencia Rd., Tucson, AZ 85706 (GPS coordinates: Latitude 32.132620, Longitude −110.965136) for further growth, as described previously for Withania somnifera (Xu et al., 2011) and Physalis crassifolia (Xu et al., 2016). A herbarium sample was deposited at the University of Arizona Natural Products Center (accession number NPCDB-11/6/10). Aerial parts of areoponically grown plants were harvested when fruits were almost mature (ca. 2 months under aeroponic growth conditions). Harvested plant materials were dried in the shade, powdered, and stored at 5 °C prior to extraction.

4.3. Extraction and isolation

The dried and powdered aerial parts of aeroponically grown P. philadelphica (300 g) were extracted with MeOH (2.0 L) in an ultrasonic bath at 25 °C for 2 h, allowed to stand for 8 h and filtered. The resulting filtrate was concentrated to afford the crude MeOH extract (62.8 g). The crude extract was subjected to solvent-solvent partitioning between hexanes and 80% aqueous MeOH. The 80% aqueous MeOH layer was diluted with H2O to provide 50% aqueous MeOH solution, which was further extracted with CHCl3. Investigation of the hexanes, CHCl3 and 50% aqueous MeOH fractions by TLC suggested that only the CHCl3 fraction contained withanolides. The CHCl3 fraction (9.8 g) was therefore subjected to column chromatography over RP C18 (80 g), and eluted with 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% aqueous MeOH and MeOH (300 mL each) to give eight fractions (A–H) according to their TLC profiles. The fraction B (116 mg) was subjected to further fractionation by RP C18 HPLC by eluting with 55% aqueous MeOH. Five sub-fractions (B-1–B-5) corresponding to the peaks at retention times (tRs) 20.5, 22.7, 32.0, 37.6, and 44.7 min were collected. The sub-fraction B-1 (14.1 mg) was further separated by a silica gel (6 g) column chromatography by eluting with 1:1 (v/v) EtOAc-CHCl3 to give 9 (9.8 mg). The sub-fraction B-2 (31.9 mg) was further separated by a silica gel (6 g) column chromatography by eluting with 1:1 and 2:1 (v/v) EtOAc-CHCl3 to give 4 (31.4 mg) and 1 (0.7 mg). The sub-fraction B-3 (4.1 mg) was further purified by a silica gel (6 g) column chromatography eluted with 2:1 (v/v) EtOAc-CHCl3 to give 3 (1.0 mg). The sub-fraction B-4 (2.6 mg) was purified by a preparative silica gel TLC [95:5 (v/v) CHCl3-MeOH] to give 6 (1.3 mg, Rf = 0.3), and the B-5 (3.2 mg) was purified by a silica gel (6 g) column chromatography by eluting with 95:5 (v/v) CHCl3-MeOH to give 2 (2.9 mg). The fraction C (215 mg) was subjected to a RP C18 HPLC byeluting with 52% aqueous MeOH, and 7 (19.8 mg, tR = 29.0 min) was obtained. A portion of fraction D (100 mg from total of 289 mg) was subjected to a RP C18 HPLC to afford 10 (57.5 mg, tR = 25.0 min, 55% aqueous MeOH). The fraction E (571 mg) was crystallized in MeOH to afford the colorless crystals of 11 (272 mg) and a mother liquid, which was subjected to a RP C18 HPLC eluted with 50% MeOH to give 5 (36.8 mg, tR = 27.1 min, 50% aqueous MeOH) and additional amount of 11 (31.6 mg, tR = 29.5 min, 50% aqueous MeOH). The fraction F (145 mg) was fractionated again on a RP C18 (10 g) column eluted with 50% aqueous MeOH to afford four sub-fractions, F-1–F-4. The sub-fraction F-2 (32.1 mg) was crystallized in MeOH to give 8 (9.1 mg).

4.3.1. 16β-hydroxyixocarpanolide (1)

White amorphous powder; (c 0.07, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 223 (3.66) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ] + 1173 (242 nm), −5340 (335 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 511.2657 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O7Na, 511.2667).

4.3.2. 24,25-Dihydroexodeconolide C (2)

White amorphous powder; (c 0.29, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 225 (3.80) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ] + 694 (242 nm), −5877 (336 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 511.2687 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O7Na, 511.2667).

4.3.3. 16,17-Dehydro-24-epi-dioscorolide A (3)

White amorphous powder; (c 0.10, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 227 (3.67) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ]) 426 (242 nm), −5875 (336 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 493.2557 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H38O6Na, 493.2561).

4.3.4. 17-Epi-philadelphicalactone A (4)

White amorphous powder; (c 2.7, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 217 (3.67) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ] + 1930 (243 nm), +4458 (339 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 511.2668 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O7Na, 511.2667).

4.3.5. 16-Deoxyphiladelphicalactone C (5)

White amorphous powder; (c 1.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 215 (3.85) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ] + 3157 (232 nm), +3938 (340 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 511.2676 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O7Na, 511.2667).

4.3.6. 4-Deoxyixocarpalactone A (6)

White amorphous powder; (c 0.13, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 222 (3.71) nm; ECD (MeOH) [θ] – 779 (241 nm), +403 (276 nm), +666 (361 nm); 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2, respectively; positive HRESIMS m/z 511.2681 [M+Na]+ (calcd for C28H40O7Na, 511.2667).

4.4. Cytotoxicity assay

The ACHN (human renal adenocarcinoma), M14 (human melanoma), SK-MEL-28 (human melanoma) and UO-31 (human kidney carcinoma) cells were all obtained from the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) (NCI, Frederick, MD). LNCaP (androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma) and HFF (human foreskin fibroblast) cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cell lines were maintained as recommended by the source institution. Cell numbers were estimated using the MTS dye assay (Promega, Madison, WI) (Brooks et al., 2010). The MTS dye assay was used for evaluating cytotoxicity of withanolides 1–11, 13 and 14 against LNCaP, ACHN, UO-31, M14 and SK-MEL-28 cell lines, and HFF cells. Doxorubicin and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. For LNCaP, ACHN, UO-31 and HFF cells, the assay was performed in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) medium with 5% FCS, 2.0 mM l-glutamine, 1 × nonessential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid] and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. For M14 and SK-MEL-28 cells, DMEM (Dulecco's Modified Eagle) medium replaced RPMI medium. Briefly, 10,0 cells (LNCaP) or 5000 cells (ACHN, UO-31, M14, SK-MEL-28, and HFF) were incubated overnight at 37 °C in 96-well microtiter plates. Serial dilutions of compounds in DMSO or vehicle control (DMSO) were added to triplicate wells and the microtiter plates were incubated for a further 72 h. Viable cell number was determined by the addition of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay solution (MTS), plates were incubated for 2 h and then the absorbance at 490 nm was measured. Cytotoxicity was calculated as in the following formula: % Cytotoxicity = [(AMedia-ATreatment)/AMedia)]*100. The IC50 values and standard deviations (±) were determined using Microsoft Excel software from dose-response curves obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission [grant number ADHS-16-162515]. The project was also funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the gs2:National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [contract number HHSN26120080001E] and [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of NIH, Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research. We thank Mr. Daniel Bunting for his help with germination and aeroponic cultivation of P. philadelphica used in this work. Ashley Babyak and Hanna Marks are also thanked for their technical assistance in conducting cytotoxicity assays. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.04.018.

References

- Abdullaev ND, Vasina OE, Maslennikova VA, Abubakirov NK, 1986. Withasteroids of Physalis VI. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of withasteroids ixocarpalactone A and ixocarpanolide. Chem. Nat. Compd 22, 300–305. [Google Scholar]

- Begley MJ, Crombie L, Ham PJ, Whiting DA, 1976. A new class of natural steroids, with ring D aromatic, from Nicandra physaloides (solanaceae). X-Ray analysis of Nic-10, and the structures of Nic-1 (‘nicandrenone’), -12, and -17. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1, 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AD, Jacobsen KM, Li W, Shanker A, Sayers TJ, 2010. Bortezomib sensitizes human renal cell carcinomas to TRAIL apoptosis through increased activation of caspase-8 in the death-inducing signaling complex. Mol. Cancer Res 8, 729–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-X, He H, Qiu F, 2011. Natural withanolides: an overview. Nat. Prod. Rep 28, 705–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary MI, Dur-e-Shahwa, Parveen Z, Jabbar A, Ali I, Atta-Ur-Rahman, 1995. Antifungal steroidal lactones from Withania coagulance. Phytochemistry 40, 1243–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang ST, Liu JK, Li B, 2012. Ten new withanolides from Physalis peruviana. Steroids 77, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotter E, 1991. Withanolides and related ergostane-type steroids. Nat. Prod. Rep 8, 415–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb HE, Kirson I, 1981. 13C NMR spectroscopy of the withanolides and other highly oxygenated C28 steroids. Org. Magn. Reson 16, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gu J-Q, Li W, Kang Y-H, Su B-N, Fong HHS, van Breemen RB, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD, 2003. Minor withanolides from Physalis philadelphica: structures, quinone reductase induction activities, and liquid chromatography (LC)-MS-MS investigation as artifacts. Chem. Pharm. Bull 51, 530–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WD Jr., 1986. In: D'Arcy WG (Ed.), Domesticated and Wild Physalis Philadelphica in Solanaceae, Biology and Systematics. Columbia University Press, pp. 416–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly EJ, Gerhäuser C, Song LL, Graham JG, Beecher CWW, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD, 1997. Induction of quinone reductase by withanolides isolated from Physalis philadelphica (Tomatillos). J. Agric. Food Chem 45, 3771–3777. [Google Scholar]

- Kindscher K, Long Q, Corbett S, Bosnak K, Loring H, Cohen M, Timmermann BN, 2012. The ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology of wild tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related Physalis species: a review. Econ. Bot 66, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kirson I, Cohen A, Greenberg M, Gottlieb HE, Glotter E, Varenne P, Abraham A, 1979. Ixocarpalactones A and B, two unusual naturally occurring steroids of the ergostane type. J. Chem. Res 103. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado E, Pérez-Castorena AL, Garcés C, Marténez M, 2011. Philadelphicalactones C and D and other cytotoxic compounds from Physalis philadelphica. Steroids 76, 724–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B-N, Misico R, Park EJ, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar AD, Fong HHS, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD, 2002. Isolation and characterization of bioactive principles of the leaves and stems of Physalis philadelphica. Tetrahedron 58, 3453–3466. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SS, Sethi PD, 1973. Steroidal lactones of Physalis ixocarpa leaves. Indian J. Pharm 35, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tewary P, Gunatilaka AAL, Sayers TJ, 2017. Using natural products to promote caspase-8-dependent cancer cell death. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 66, 223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li Z, He C, 2012. Transcriptome-wide mining of the differentially expressed transcripts for natural variation of floral organ size in Physalis philadelphica. J. Exp. Bot 63, 6457–6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson M, Manos PS, 2005. Untangling Physalis (solanaceae) from the physaloids: a two-genes phylogeny of the physalinaeae. Syst. Bot 30, 216–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne EMK, Xu Y, Scherz-Shouval R, Marron MT, Rocha DD, Liu MX, Costa-Lotufo LV, Santagata S, Lindquist S, Whitesell Luke, Gunatilaka AAL, 2014. Structure-activity relationships for withanolides as inducers of the cellular heat-shock response. J. Med. Chem 57, 2851–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Gao S, Bunting DP, Gunatilaka AAL, 2011. Unusual withanolides from aeroponically grown Withania somnifera. Phytochemistry 72, 518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Liu MX, Grunow N, Wijeratne EMK, Paine-Murrieta G, Felder S, Kris RM, Gunatilaka AAL, 2015. Discovery of potent 17β-hydroxywithanolides for castration-resistant prostate cancer by high-throughput screening of a natural products library for androgen-induced gene expression inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 58, 6984–6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Bunting DP, Liu MX, Bandaranayake HA, Gunatilaka AAL, 2016. 17β-Hydroxy-18-acetoxywithanolides from aeroponically grown Physalis crassifolia and their potent and selective cytotoxicity for prostate cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod 79, 821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Wijeratne EMK, Babyak AL, Marks HR, Brooks AD, Tewary P, Xuan L, Wang W, Sayers TJ, Gunatilaka AAL, 2017. Withanolides from aeroponically grown Physalis peruviana and their selective cytotoxicity to prostate cancer and renal carcinoma cells. J. Nat. Prod 80, 1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B-Y, Xia Y-G, Pan J, Liu Y, Wang Q-H, Kuang H-X, 2016. Phytochemistry and biosynthesis of δ-lactone withanolides. Phytochem. Rev 15, 771–797. [Google Scholar]

- Yu M-Y, Zhao G-T, Liu J-Q, Khan A, Peng X-R, Zhou L, Dong J-R, Li HZ, Qiu M-H, 2017. Withanolides from aerial parts of Nicandra physalodes. Phytochemistry 137, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.