Abstract

Background

Understanding the source of newly detected human papillomavirus (HPV) in middle-aged women is important to inform preventive strategies, such as screening and HPV vaccination.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study in Baltimore, Maryland. Women aged 35–60 years underwent HPV testing and completed health and sexual behavior questionnaires every 6 months over a 2-year period. New detection/loss of detection rates were calculated and adjusted hazard ratios were used to identify risk factors for new detection.

Results

The new and loss of detection analyses included 731 women, and 104 positive for high-risk HPV. The rate of new high-risk HPV detection was 5.0 per 1000 woman-months. Reporting a new sex partner was associated with higher detection rates (adjusted hazard ratio, 8.1; 95% confidence interval, 3.5–18.6), but accounted only for 19.4% of all new detections. Among monogamous and sexually abstinent women, new detection was higher in women reporting ≥5 lifetime sexual partners than in those reporting <5 (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.2–4.2).

Conclusion

Although women remain at risk of HPV acquisition from new sex partners as they age, our results suggest that most new detections in middle-aged women reflect recurrence of previously acquired HPV.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, cervical neoplasia, epidemiology, sexual behavior, cervical cancer screening

New human papillomavirus (HPV) detection in adult women is a mixture of newly acquired infection and recurrent detection of past infection. These data are important for shared decision making regarding HPV screening and vaccination throughout the life span.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted virus [1]. The prevalence of HPV peaks shortly after sexual debut, and the risk of having a new HPV infection detected increases with increasing number of sexual partners [2, 3]. Most HPV infections become undetectable within 1–2 years, a phenomenon typically defined as viral clearance [4]; however, recent studies have suggested that the virus may not be completely eradicated but rather may enter a latent state in the basal cell layer of the cervical epithelium [5, 6], with subsequent loss of immune control possibly resulting in redetection of the virus [7, 8]. Thus, new HPV detection may represent a mixture of new acquisition and redetection of previously acquired infections, particularly in middle-aged women many years past sexual debut [9, 10].

We previously reported the rates of new HPV detection in an interim analysis of a large prospective cohort of well-screened, middle-aged women in Baltimore, Maryland [10]. In that analysis, relative risk of new detection by current and past sexual behavior was estimated using an infection-level analysis, which allows all women with HPV to be at-risk for new HPV genotypes. In the current analysis, we report (1) the risk of new high-risk (HR) HPV detection using complete follow-up time, from a clinical screening perspective, where women move from “HR HPV negative” to “HR HPV positive” and (2) a new loss-of-detection analysis to provide a more complete understanding of the woman-level transitions in HPV detectability by current and past sexual behavior.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We conducted a prospective cohort study in Baltimore, Maryland, from March 2008 to March 2011. Women were enrolled in the HPV in Perimenopause study if they were aged 35–60 years, had an intact cervix, and provided informed consent. Women were excluded if they were pregnant, had plans to become pregnant within the next 2 years, had a history of organ transplantation, or were seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Women were followed up every 6 months for 2 years. At baseline and every 6-month visit, a trained study physician or registered nurse collected an exfoliated cell sample from the cervix using the Digene HPV cervical brush. Information on sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive health, and sexual history was collected using questionnaires at baseline (administered via telephone) and at each follow-up visit (administered in person or by telephone).

All study protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. To conduct this analysis, additional approval was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Exfoliated cervical cell samples were HPV genotyped using the Roche HPV Linear Array polymerase chain reaction–based assay (Roche Diagnostics), as described elsewhere [10]. The Roche HPV Linear Array detects 37 distinct HPV types, including all HR HPV types. For the current analysis, “any HPV type” refers to any of the following 37 HPV types: 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 (MM9), 81, 82 (MM4), 83 (MM7), 84 (MM8), IS39, and CP6108; “any HR HPV type” refers to any of the following 13 types: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68; and “any nonvalent HPV type” refers to any of the following 2 low-risk or 7 HR HPV types: 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

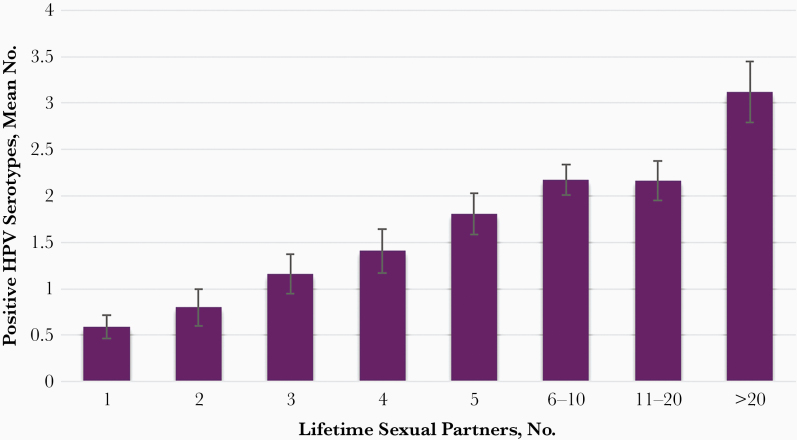

At enrollment, serum samples were collected to determine serostatus for 8 HPV types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, and 52) using a viruslike-particle based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as described elsewhere [11, 12]. Of women enrolled, a total of 719 (75.6%) had serum samples available, 447 (62.2%) of which had ≥1 HPV type detected. As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of HPV types detected by serology was positively correlated with the number of self-reported lifetime sexual partners (LTSPs), suggesting that this number can be used as surrogate measure of cumulative exposure to HPV. Based on these findings, we stratified previous exposure to HPV in 2 risk categories: 1–4 versus ≥5 LTSPs.

Figure 1.

Number of human papillomavirus (HPV) serotypes detected among women aged 35–60 years in Baltimore, Maryland, stratified by the number of lifetime sexual partners.

Statistical Analysis

For the current analysis, women were included if they had completed the baseline questionnaire, had valid HPV DNA results at baseline, and had ≥1 follow-up visit. In the analysis of new detections, women were considered at risk for a maximum of 37 HPV types. A woman would not be considered at risk for detection of any new HPV, any new HR HPV, or any new nonvalent HPV if she tested positive at baseline for an HPV type in a given group. Rates of new detection in a given group (ie, any HPV, any HR HPV, or any nonvalent HPV) were calculated by dividing the number of women with ≥1 new HPV detections by person-time at risk.

Women contributed time at risk starting at baseline (if negative for the relevant HPV types in the group analysis) and ending at the date of the first HPV detection in a given group or at the last study visit if they remained HPV negative. Loss of HPV detection was defined as 2 consecutive type-specific negative results or if HPV was undetectable at the last study visit. Rates of loss of detection were calculated by dividing the number of women with loss of detection by person-time at risk (HR HPV only). Women contributed time at risk starting on the date of HPV detection (new or prevalent) and ending at the date of loss of detection or at the last study visit. Infections detected at the last study visit did not contribute person-time to the loss of detection analysis.

If an HPV result was missing between 2 nonmissing results, the prior nonmissing HPV DNA result was carried forward. Results were similar when using carry-backward imputation. The cumulative probability of new HPV detection or loss of detection was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

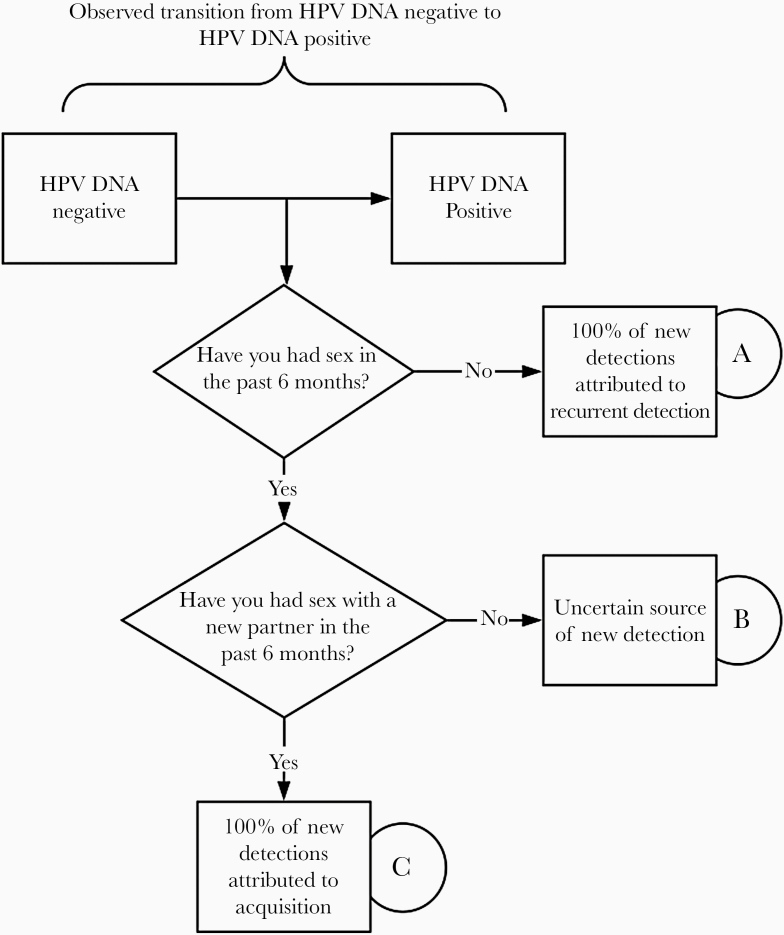

We calculated the relative risk of new HPV detection according to self-reported current sexual activity, as outlined in Figure 2. Group A included women with no sexual activity in the previous 6 months; group B, those with sexual activity with same partner as in the previous time period; and group C, those with sexual activity with a new partner in the past 6 months. For group A, we assumed that 100% of new HPV detections occurred as a result of recurrent detection of a previously acquired infection (ie, reactivation, autoinoculation, or increase in viral load to detectable limits). For group B, the source of new detection was considered uncertain because acquisition could have occurred through the unmeasured sexual behavior of the male partner, while new detection in group C was conservatively assumed to occur as a result of acquisition from the new partner.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model for estimating proportion of new human papillomavirus (HPV) detections attributed to new acquisition versus detection of recurrent, previously acquired infection (ie, reactivation).

We used the number of LTSPs as a surrogate measure of cumulative exposure to HPV infection and risk of harboring a latent infection (Figure 2). We calculated unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios of new HPV detection using group A (no sexual activity in the previous 6 months) as the reference group. To focus on the most parsimonious risk estimation for the primary exposures of sexual behavior, we adjusted only for variables that changed the point estimate by 10% (ie, marital status). Results were reported overall and stratified by the number of LTSPs (ie, <5 or ≥5), to determine whether risk of new HPV detection differed by cumulative HPV exposure. For simplicity, only results for HR HPV are reported in the text, unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were conducting using Stata 15 software (StataCorp).

RESULTS

A total of 951 women were enrolled in the study, 731 of whom were included in the new detection analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). The loss of detection analysis was restricted to 104 women who had ≥1 HR HPV type detected at baseline or during follow-up, excluding women who had HR HPV detected at the last study visit (n = 26). More than half of the women completed all study visits, 175 (23.9%) had ≥1 missing in-between visit, and 165 (22.6%) completed visits until loss to follow-up. Of these, 88 (12.0%) had only 1 follow-up visit. The median follow-up time was 24.5 months (interquartile range, 19.0–25.9 months. Frequency distributions of the cohort demographics, sexual, and reproductive characteristics overall and by age category are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic Characteristics of Study Cohort

| Women, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All Ages (n = 731) | Age 35–49 y (n = 466) | Age 50–60 y (n = 265) |

| Race | |||

| White | 548 (75.0) | 342 (73.4) | 206 (77.7) |

| Black | 132 (18.1) | 88 (18.9) | 44 (16.6) |

| Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 25 (3.4) | 19 (4.1) | 6 (2.3) |

| American Indian | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Not reported | 24 (3.3) | 16 (3.4) | 8 (3.0) |

| Highest educational level completed | |||

| High school | 117 (16.0) | 78 (16.7) | 39 (14.7) |

| Beyond high school | 164 (22.4) | 105 (22.5) | 59 (22.3) |

| College/postgraduate | 450 (61.6) | 283 (60.7) | 167 (63.0) |

| Yearly income | |||

| <$40 000 | 55 (7.5) | 34 (7.3) | 21 (7.9) |

| $40 000–$80 000 | 196 (26.8) | 131 (28.1) | 65 (24.5) |

| $80 000–$120 000 | 173 (23.7) | 116 (24.9) | 57 (21.5) |

| >$120 000 | 244 (33.4) | 151 (32.4) | 93 (35.1) |

| Unknown | 63 (8.6) | 34 (7.3) | 29 (10.9) |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never | 476 (65.1) | 307 (65.9) | 169 (63.8) |

| Former | 182 (24.9) | 106 (22.8) | 76 (28.7) |

| Current | 73 (10.0) | 53 (11.4) | 20 (7.6) |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Premenopausal | 467 (63.9) | 301 (64.6) | 166 (62.6) |

| Postmenopausal | 231 (31.6) | 146 (31.3) | 85 (32.1) |

| Missing | 33 (4.5) | 19 (4.1) | 14 (5.3) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 464 (63.5) | 291 (62.5) | 173 (65.3) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 133 (18.2) | 76 (16.3) | 57 (21.5) |

| Never married | 134 (18.3) | 99 (21.2) | 35 (13.2) |

| Lifetime sexual partners | |||

| <5 | 277 (37.9) | 162 (34.8) | 115 (43.4) |

| ≥5 | 453 (62.0) | 303 (65.0) | 150 (56.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sexual behavior | |||

| No recent sex | 112 (15.3) | 57 (12.2) | 55 (20.8) |

| Recent sex, same partner | 534 (73.1) | 349 (74.9) | 185 (69.8) |

| Recent sex, new partner | 85 (11.6) | 60 (12.9) | 25 (9.4) |

| Current hormone use | |||

| No | 554 (75.8) | 316 (67.8) | 238 (89.8) |

| Yes | 177 (24.2) | 150 (32.2) | 27 (10.2) |

| Any history of sexually transmitted infection (self-report)a | |||

| No | 412 (56.4) | 260 (55.8) | 152 (57.4) |

| Yes | 319 (43.6) | 206 (44.2) | 113 (42.6) |

| Any history of abnormal Papanicolaou test results (self-report) | |||

| No | 387 (52.9) | 242 (51.9) | 145 (54.7) |

| Yes | 336 (46.0) | 219 (47.0) | 117 (44.2) |

| Data missing | 8 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) |

aReport of ever receiving a diagnosis of chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, trichomonas, syphilis, chancroid, bacterial vaginosis, or genital warts.

At baseline, the overall prevalence of any HPV type was 18.6%, while the prevalences of any HR HPV and any nonvalent HPV type were 8.5% and 5.8%, respectively (Table 2). HPV-16 was the most prevalent HPV type. Crude prevalence rates were slightly higher in women aged 35–49 years than in those aged 50–60 years.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) at Baseline and Rates of New HPV Detection Among Middle-aged Women, Overall and Stratified by Age at Baseline

| Cumulative New Detections, % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Type by Age | Prevalence at Enrollment, % | Duration of Follow-up, Woman-Months | Incident Infections, No. | 12 mo | 24 mo | New Detections, No./1000 Woman-Months (95% CI) |

| Any type by age, y | ||||||

| All ages | 18.6 | 11 457 | 110 | 12.1 | 20.9 | 9.6 (8.0–11.6) |

| 35–49 | 20.4 | 7062 | 79 | 14.4 | 23.9 | 11.2 (9.0–14.0) |

| 50–60 | 15.5 | 4389 | 31 | 8.3 | 16.0 | 7.1 (5.0–10.0) |

| Any HR type by age, y | ||||||

| All ages | 8.5 | 13 745 | 68 | 5.4 | 11.8 | 5.0 (3.9–6.3) |

| 35–49 | 10.5 | 8539 | 47 | 6.4 | 13.2 | 5.5 (4.1–7.3) |

| 50–60 | 4.9 | 5206 | 21 | 3.6 | 9.5 | 4.0 (2.6–6.2) |

| Any nonvalent type by age, y | ||||||

| All ages | 5.8 | 14 311 | 54 | 3.9 | 9.1 | 3.8 (2.9–4.9) |

| 35–49 | 6.9 | 9007 | 37 | 4.3 | 10.2 | 4.1 (3.0–5.7) |

| 50–60 | 3.8 | 5304 | 17 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 3.2 (2.0–5.2) |

| Specific HPV type | ||||||

| 6 | 0.6 | 15 723 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 (.1–.7) |

| 11 | 0.1 | 15 819 | 0 | … | … | … |

| 16 | 1.6 | 15 353 | 15 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.0 (.6–1.6) |

| 18 | 1.0 | 15 555 | 10 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 (.4–1.2) |

| 31 | 0.4 | 15 699 | 7 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 (.2–.9) |

| 33 | 0.6 | 15 697 | 3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 (.1–.6) |

| 45 | 0.6 | 15 637 | 11 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 0.7 (.4–1.3) |

| 52 | 1.0 | 15 566 | 14 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 0.9 (.5–1.5) |

| 58 | 0.6 | 15 710 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 (.1–.7) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, high-risk.

Detection rates of new HPV were 9.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.0–11.6) per 1000 woman-months for any HPV type, 5.0 (3.9–6.3) per 1000 woman-months for any HR HPV type, and 3.8 (2.9–4.9) per 1000 woman-months for any nonvalent HPV type. HPV-16 was the most common newly detected HPV type, with a new detection rate of 1.0 (95% CI, .6–1.6) per 1000 woman-months (Table 2).

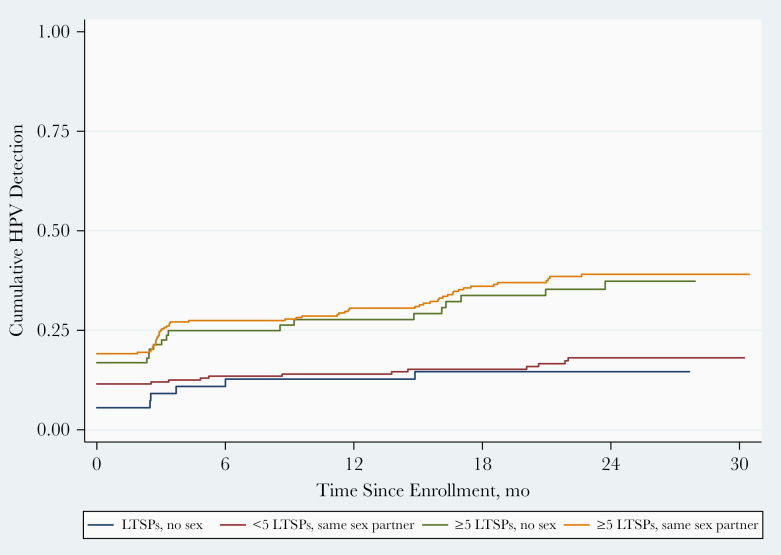

Among women with new HR HPV detections, 13 (19.4%) of detections occurred among women who reported having had a new sexual partner, 46 (68.7%) among monogamous women, and 8 (11.9%) among sexually abstinent women. Recent sexual activity with a new partner was associated with the highest rate of new HR HPV detection, regardless of past sexual behavior and age (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1). There was no significant difference in new HR HPV detection rates between women who reported no recent sex and those who reported having sex with the same partner (Figure 3). When exploring the impact of past sexual behavior on risk of new HR HPV detection among women who reported having no new sex partner, women with ≥5 LTSPs were 2.2-fold more likely to have HPV detected than those with <5 LTSPs (P < .001) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Rates of Any New High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Detection Among Middle-aged Women, Stratified by Recent and Previous Sexual Behavior and Age

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age and Sexual Behaviora | Duration of Follow-up, Woman-Months | New Detection Events, No. | New Detections, No./1000 Woman-Months (95% CI) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb |

| Age 35–49 y | |||||

| Same partner or no sex | |||||

| <5 LTSPs | 3094 | 8 | 2.6 (1.3–5.2) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| ≥5 LTSPs | 4943 | 31 | 6.3 (4.4–8.9) | 2.4 (1.1–5.2) | 2.2 (1.0–4.9) |

| New partner (<5 or ≥5 LTSPs) | 334 | 7 | 21.0 (10.0–44.0) | 8.1 (2.9–22.2) | 5.6 (2.0–16.3) |

| Age 50–60 y | |||||

| Same partner or no sex | |||||

| <5 LTSPs | 2356 | 4 | 1.7 (.6–4.5) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| ≥5 LTSPs | 2639 | 11 | 4.2 (2.3–7.5) | 2.4 (.8–7.5) | 1.9 (.6–6.3) |

| New partner (<5 or ≥5 LTSPs) | 149 | 6 | 40.3 (18.1–89.7) | 27.2 (7.5–98.4) | 14.11 (3.4–59.1) |

| All ages | |||||

| Same partner or no sex | |||||

| <5 LTSPs | 5450 | 12 | 2.2 (1.3–3.9) | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.0 (Reference) |

| ≥5 LTSPs | 7582 | 42 | 5.5 (4.1–7.5) | 2.5 (1.3–4.7) | 2.2 (1.2–4.2) |

| New partner (<5 or ≥5 LTSPs) | 483 | 13 | 26.9 (15.6–46.4) | 12.6 (5.8–27.7) | 8.1 (3.5–18.6) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTSPs, lifetime sexual partners.

aWomen reporting the same partner (group B) and those reporting no sex (group A) (both groups defined in Supplementary Figure 1) were combined, because we found no significant difference in rates of new HPV detection between the groups.

bHazard ratios adjusted for marital status.

Figure 3.

Rates of new human papillomavirus (HPV) detection by recent and past sexual behavior among women aged 35–60 years in Baltimore, Maryland. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating new detection rates for women who reported having sex with the same partner or no sex, stratified by the number of lifetime sexual partners (LTSPs).

With respect to the most commonly detected genotype, HPV-16, rates of new detection were highest in women reporting a new sex partner (3.1 [95% CI, .8–12.4] per 1000 woman-months), followed by women reporting sex with the same partner (1.0 [.6–1.8] per 1000 woman-months) and sexually abstinent women (0.6 [.2–2.4] per 1000 woman-months).

Among 104 women with a baseline or new HR HPV infection, 58 loss of detection events were observed (44.1 [95% CI, 34.1–57.1] per 1000 woman-months) (Table 4). The loss of detection rate (95% CI) was 33.3 (23.6–47.1) per 1000 woman-months for women with prevalent infections at baseline compared with 73.4 (50.0–107.8) per 1000 woman-months for women negative for HR HPV at baseline with new HR HPV detected during follow-up. Differences in loss of detection were observed across genotypes, with HPV-16 and HPV-45 having the lowest loss of detection rates and HPV-33 and HPV-58 the highest. The loss of detection rate was slightly lower in women aged 50–60 years than in those aged 35–49 years. We found no difference in loss of detection rates by past and recent sexual behavior (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4.

Loss of Detection of Any High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Among Middle-aged Women, Overall and Stratified by Age at Baseline

| Cumulative Loss of Detection, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Type | Duration of Follow-up, Woman-Months | Loss of Detection Events, No. | 12 mo | 24 mo | Loss of Detection Events, No./1000 Woman-Months (95% CI) |

| Any HR type | |||||

| All ages | 1315 | 58 | 46.9 | 64.6 | 44.1 (34.1–57.1) |

| Age 35–49 y | 951 | 45 | 50.3 | 68.2 | 47.3 (35.3–63.4) |

| Age 50–60 y | 364 | 13 | 38.4 | 54.4 | 35.7 (20.7–61.4) |

| Prevalent | 961 | 32 | 37.4 | 58.1 | 33.3 (23.6–47.1) |

| New detection | 354 | 26 | 61.8 | NAa | 73.4 (50.0–107.8) |

| Specific HPV type | |||||

| 6 | 45 | 3 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 67.2 (21.7–208.23) |

| 11 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 365 | 5 | 14.4 | 27.6 | 13.7 (5.7–32.9) |

| 18 | 184 | 5 | 39.2 | 38.2 | 27.2 (11.3–65.4) |

| 31 | 65 | 3 | 65.7 | NAa | 45.8 (14.8–142.1) |

| 33 | 55 | 4 | 50.0 | NAa | 72.4 (27.2–192.9) |

| 45 | 136 | 1 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.3 (1.0–52.1) |

| 52 | 149 | 4 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 26.8 (10.0–71.3) |

| 58 | 53 | 4 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 75.8 (28.4–201.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; HR, high-risk; NA, not available.

aWe were unable to calculate these estimates because we did not have enough follow-up time to look at 24-month cumulative loss of detection.

DISCUSSION

Middle-aged women with a recent new sexual partner have higher rates of new HPV detection, supporting the premise that individuals remain at risk for HPV acquisition throughout the life span. Given the high clearance rates observed from newly detected HPV, rapid control to undetectable levels appears to be the usual response. However, only 19% of all newly detected HR HPV infections occurred in women reporting a new sexual partner, while 12% occurred in sexually inactive women and 69% in women having sex with the same partner. Because the rates of new HR HPV detection in women reporting no sexual activity were similar to rates in women reporting sex with the same partner, new exposure from the unreported sexual behavior of the male partner appears to be minimal in this study population. Rates of new HR HPV detection in women without a new sexual partner were >2-fold higher among those reporting ≥5 LTSPs, who are at higher risk of harboring a nonproductive or latent HPV. Taken together, these data may suggest that a substantial proportion of new HR HPV detection in middle-aged women reflects recurrent detectability of a previously acquired infection.

These results confirm data from an interim analysis of the HPV in Perimenopause cohort [10], a higher-risk cohort of older women in Seattle, Washington [9], and data from a large cohort of unvaccinated men [13, 14]. Recurrent detection may reflect reactivation of infection from a latent state, autoinoculation from another epithelial site (eg, vulvovaginal or anal infection), or false-negative/false-positive test results. The differential risk in women with a higher number of LTSPs suggests that reactivation and autoinoculation are more likely explanations than misclassification of test results, which would be expected to be nondifferential by cumulative exposure risk. Data reporting high anal HPV prevalence and widespread infection in the vulvovaginal epithelium [15] would support the possibility of autoinoculation, while recent reports by Hammer et al [5] and others [16], as well as elegant animal papillomavirus models of latency [6, 8], support the possibility of focal latent infection of the cervix. High-density sampling of anal, vulvovaginal, and cervical HPV with daily sexual behavior data will be needed to differentiate these 2 mechanisms of recurrent detectability.

Our findings have several important clinical implications. First, as HPV testing becomes a routine part of early detection and treatment programs, women will be accumulating their own individual HPV natural history profiles. Our data may help with counseling sexually abstinent women and women in monogamous relationships who may be concerned about the source of new HPV infection. These data also reinforce the need for continued routine screening in sexually inactive or sexually monogamous women, even if their last screening result was HPV negative. Second, HPV vaccines are now approved by the US Food and Drug Association for use in individuals up to age 45 years [17], though most professional organizations, including the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have not made specific recommendations for vaccination in those aged 27–45 years; instead they recommend shared decision making between patient and provider to weigh risks and benefits on a case-by-case basis.

Although there is no definitive study to show whether prophylactic HPV vaccination may prevent recurrent detection, the significantly reduced population effectiveness in women receiving the vaccine in early adulthood, presumably after sexual debut [18, 19], suggests that the vaccine may have minimal benefit in reducing reactivation risk. On the other hand, some [20, 21] but not all [22, 23] studies have shown that vaccination of individuals after conization reduced risk of disease recurrence, suggesting some immunologic boosting or possible prevention of lateral spread of infection. Randomized controlled trials will be needed to confirm the benefit of reducing recurrent disease in treated individuals and evaluate whether this can be extended to increased control of latent infection in asymptomatic women.

The clinically important question is whether there is a differential risk of cervical precancer and cancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] 3+) in women with redetection compared with those with a newly acquired infection. Although our study was not designed or powered to evaluate this question, a previous study reported that potential reactivated infections were associated with similar risks of CIN2+ compared with newly acquired infections [24]. A recent study from a large US health system showed a substantial number of women with HPV testing patterns reflective of newly detected and reappearing infection [25]. These data show that an HPV-positive test result is strongly predictive of CIN3+ diagnosis, whether detected as a baseline screening test or preceded by positive or negative prior tests, with incidence rates of CIN3+ ranging from 792/100 000 in women with 3 prior negative tests to 2449/100 000 in women with 3 prior positive tests, and 1223/100 000 in women with intermittent HPV detection (compared with 18/100 000 in women with 4 consecutive negative HPV tests). In light of these results, it will be important to understand whether the higher cumulative exposure to HPV in post–sexual revolution birth cohorts will translate to an increased risk of positive screening tests in more recent birth cohorts currently entering menopause [26–28]. A proportionate increase in postmenopausal HPV-infected women is concerning, given the well-known limitations of morphologic screening and diagnosis after menopause [29, 30].

The impact of cohort effects and latency on cancer risk throughout the life span are currently not possible to estimate with empirical data. Many screening and vaccination recommendations are thus based on expert opinion and health decision models. However, most health decision models do not account explicitly for controlled (latent) HPV infection [31], owing to limited data on (1) the proportion of infections that become undetectable that are in fact in a latent state, (2) the transition risk for redetection of latent infections as a function of age, and (3) the relative risk of progression to precancer among redetected versus newly acquired infections. These unknowns may vary between populations, depending on differences in cell-mediated immunity.

Modeling efforts in recent years have evaluated the impact of including a “latent-reactivated transition” in the lifetime natural history in men and women, and they have largely concluded that inclusion of this transition improved model fit [28, 32]. Given the evidence that latency is part of the natural history of HPV infection [5, 6, 8, 16] and the present finding that there is likely to be heterogeneity in the risk of redetection in a population according to cumulative lifetime HPV exposure, it would be of great interest for health decision models to assess the potential impact of incorporating latency and redetection on policy decisions. The extent to which changes in model structure will be necessary depends in part on whether HPV incidence is directly estimated from current sexual behavior data or whether the models are agnostic regarding the source of newly detectable infections in older women (ie, whether acquired through recent, as opposed to past, sexual behavior).

It would be worth investigating whether models fully capture population heterogeneity in cumulative HPV exposure over the life span, and, if not, whether such heterogeneity might affect model predictions when evaluating interventions such as adult HPV vaccination and age at which to end screening. The impact of including latency and redetection in a model is likely to be most relevant for HPV transmission models that are used to evaluate HPV vaccination strategies involving middle-aged women. To evaluate proposed vaccination strategies involving middle-aged and older women, transmission models should consider whether distinguishing the new acquisition of HPV by age from reactivated infections by age leads to different policy conclusions. The overall impact of this distinction will also depend on the level of effectiveness of vaccination against reactivated infections, which remains uncertain. Given that most model-based analyses of vaccination have attributed detected HPV in older women to new infections, the results have been biased in favor of vaccinating middle-aged women [33–35]. Thereby, to the extent that HPV vaccines may not be efficacious against reactivated infections, results from current model-based analyses may have overestimated the benefit and cost-effectiveness of vaccinating middle-aged and older women.

We acknowledge some important limitations to this analysis. First, the HPV detection assay used is not a clinical assay, which may have resulted in slightly higher detection rates than with Food and Drug Administration–approved HPV screening tests, in which the sensitivity of the assay is attenuated to maximize the sensitivity and specificity of the test for detection of CIN2+. Second, because our results are based on a low-risk, well-screened population, new detection and loss of detection rates may not be representative of higher-risk populations. Third, we cannot exclude recall bias or social desirability bias, in that women who reported no new sex partner may have had a new partner, which may have resulted in underestimation of new detection rates among women who reported having a new sexual partner and overestimation of rates among those reporting no new partner. In addition, we cannot rule out an underreporting of the number of LTSPs, which may have resulted in an underestimation of rates among women with ≥5 LTSPs and an overestimation among those with <5 LTSPs. However, these results have been consistent across other populations of older, US women, suggesting that these biases are unlikely to completely explain our observations [14, 36].

In conclusion, the within-woman natural history of HPV infection appears to include dynamic transitions between detection and nondetection of immunologically controlled infections. Women with a higher risk of harboring latent infection (ie, those reporting a higher number of LTSPs) will have a higher risk of new detection in screening. Given that other studies suggest that risk of cervical precancer from recurrent HPV detection is similar to that from presumed newly acquired infection, sexual history may be an important consideration in deciding when to exit screening. Study findings are inconclusive regarding the benefit of HPV vaccination in preventing recurrent detection, and randomized trials are needed to more directly estimate the impact of prophylactic vaccination on control of latent infections and reduced risk of HPV persistence and progression to cervical precancer.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01CA123467) and the Danish Cancer Society (grant to A. H.).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. H has received speaker fees from Astra Zeneca, Denmark, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Syrjänen K, Hakama M, Saarikoski S, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and estimated life-time risk of cervical human papillomavirus infections in a nonselected Finnish female population. Sex Transm Dis 1990; 17:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202:1789–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burchell AN, Winer RL, de Sanjosé S, Franco EL. Chapter 6: epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection. Vaccine 2006; 24(suppl 3):52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2007; 370:890–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hammer A, de Koning MN, Blaakaer J, et al. Whole tissue cervical mapping of HPV infection: Molecular evidence for focal latent HPV infection in humans. Papillomavirus Res 2019; 7:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maglennon GA, McIntosh P, Doorbar J. Persistence of viral DNA in the epithelial basal layer suggests a model for papillomavirus latency following immune regression. Virology 2011; 414:153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu SH, Cummings DA, Zenilman JM, Gravitt PE, Brotman RM. Characterizing the temporal dynamics of human papillomavirus DNA detectability using short-interval sampling. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23:200–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maglennon GA, McIntosh PB, Doorbar J. Immunosuppression facilitates the reactivation of latent papillomavirus infections. J Virol 2014; 88:710–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fu TC, Carter JJ, Hughes JP, et al. Re-detection vs. new acquisition of high-risk human papillomavirus in mid-adult women. Int J Cancer 2016; 139:2201–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rositch AF, Burke AE, Viscidi RP, Silver MI, Chang K, Gravitt PE. Contributions of recent and past sexual partnerships on incident human papillomavirus detection: acquisition and reactivation in older women. Cancer Res 2012; 72:6183–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rettig EM, Fakhry C, Rositch AF, et al. Race is associated with sexual behaviors and modifies the effect of age on human papillomavirus serostatus among perimenopausal women. Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viscidi RP, Snyder B, Cu-Uvin S, et al. Human papillomavirus capsid antibody response to natural infection and risk of subsequent HPV infection in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ranjeva SL, Baskerville EB, Dukic V, et al. Recurring infection with ecologically distinct HPV types can explain high prevalence and diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:13573–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rositch AF, Patel EU, Petersen MR, Quinn TC, Gravitt PE, Tobian AAR. Importance of lifetime sexual history on the prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among unvaccinated adults in NHANES: implications for adult HPV vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 2020; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodman MT, Shvetsov YB, McDuffie K, et al. Sequential acquisition of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of the anus and cervix: the Hawaii HPV Cohort Study. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:1331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep 2016; 6:20847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old. Accessed 12 March 2020.

- 18. Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Lam JO, et al. Effectiveness of catch-up human papillomavirus vaccination on incident cervical neoplasia in a US health-care setting: a population-based case-control study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018; 2:707–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dehlendorff C, Sparen P, Baldur-Felskov B, et al. Effectiveness of varying number of doses and timing between doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against severe cervical lesions. Vaccine 2018; 36:6373–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kang WD, Choi HS, Kim SM. Is vaccination with quadrivalent HPV vaccine after loop electrosurgical excision procedure effective in preventing recurrence in patients with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2-3)? Gynecol Oncol 2013; 130:264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghelardi A, Parazzini F, Martella F, et al. SPERANZA project: HPV vaccination after treatment for CIN2. Gynecol Oncol 2018; 151:229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sand FL, Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Dehlendorff C. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse after conization in relation to HPV vaccination status. Int J Cancer 2020; 147:641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hildesheim A, Gonzalez P, Kreimer AR, et al. Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 and 18 vaccination on prevalent infections and rates of cervical lesions after excisional treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 215:212e1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodríguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al. Low risk of type-specific carcinogenic HPV re-appearance with subsequent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3. Int J Cancer 2012; 131:1874–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammer A, Demarco M, Campos N, et al. Study of the risks of CIN3+ detection after multiple rounds of HPV testing: results of the 15-year cervical cancer screening experience at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Int J Cancer 2020; 147:1612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ryser MD, Rositch A, Gravitt PE. Modeling of US human papillomavirus (HPV) seroprevalence by age and sexual behavior indicates an increasing trend of HPV infection following the sexual revolution. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gravitt PE, Rositch AF, Silver MI, et al. A cohort effect of the sexual revolution may be masking an increase in human papillomavirus detection at menopause in the United States. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brouwer AF, Meza R, Eisenberg MC. Integrating measures of viral prevalence and seroprevalence: a mechanistic modelling approach to explaining cohort patterns of human papillomavirus in women in the USA. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2019; 374:20180297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hammer A, Hee L, Blaakær J, Gravitt P. Temporal patterns of cervical cancer screening among danish women 55 years and older diagnosed with cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2018; 22:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammer A, Soegaard V, Maimburg RD, Blaakaer J. Cervical cancer screening history prior to a diagnosis of cervical cancer in Danish women aged 60 years and older—a national cohort study. Cancer Med 2019; 8:418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malagón T, Kulasingam S, Mayrand MH, et al. Age at last screening and remaining lifetime risk of cervical cancer in older, unvaccinated, HPV-negative women: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19:1569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Schalkwyk C, Moodley J, Welte A, Johnson LF. Estimated impact of human papillomavirus vaccines on infection burden: The effect of structural assumptions. Vaccine 2019; 37:5460–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Portnoy A, Campos NG, Sy S, et al. Impact and cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination campaigns. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2020; 29:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laprise JF, Chesson HW, Markowitz LE, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination through age 45 years in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172:22–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim JJ, Ortendahl J, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical cancer screening in women older than 30 years in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:538–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses 2017; 9:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.