Abstract

Celiac disease (CD) is characterized by clinical polymorphism, with classic, asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic, and extra-intestinal forms, which may lead to diagnostic delay and exposure to serious complications. CD is a multidisciplinary health concern involving general medicine, pediatric, and adult gastroenterology, among other disciplines. Immunology and pathology laboratories have a fundamental role in diagnosing and monitoring CD. The diagnosis consists of serological testing based on IgA anti-transglutaminase (TG2) antibodies combined with IgA quantification to rule out IgA deficiency, a potential misleading factor of CD diagnosis. Positive TG2 serology should be corroborated by anti-endomysium antibody testing before considering an intestinal biopsy. Owing to multiple differential diagnoses, celiac disease cannot be confirmed based on serological positivity alone, nor on isolated villous atrophy. In children with classical signs or even when asymptomatic, with high levels of CD-linked markers and positive HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8 molecules, the current trend is to confirm the diagnosis on basis of the non-systematic use of the biopsy, which remains obligatory in adults. The main challenge in managing CD is the implementation and compliance with a gluten-free diet (GFD). This explains the key role of the dietitian and the active participation of patients and their families throughout the disease-management process. The presence of the gluten in several forms of medicine requires the sensitization of physicians when prescribing, and particularly when dispensing gluten-containing formulations by pharmacists. This underlines the importance of the contribution of the pharmacist in the care of patients with CD within the framework of close collaboration with physicians and nutritionists.

Keywords: Celiac disease, diagnosis, gluten-free diet, gluten-free drugs

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated systemic disorder triggered by gluten consumption, occurring in genetically predisposed individuals.1–3 Gluten refers to insoluble cereal proteins, including prolamins found in wheat (gliadins), rye (secalins), barley (hordein), and oats (avenins). However, the amino acid sequences inducing CD-associated immune reactions are less prevalent in avenins, which explains the tolerance of small amounts of oats by patients with CD.4

Unlike CD, recently described gluten sensitivity is characterized by negative serological tests and the absence of villous atrophy, and despite the presence of intestinal or extra-intestinal symptoms, it can be resolved by a gluten-free diet (GFD).5,6

In spite of the classical symptoms strongly suggestive of CD, the last decades have seen the emergence of asymptomatic, oligosymptomatic, or extra-intestinal often misleading forms; hence, the diagnostic delay and the risk of potentially serious complications7–10 can be avoided by implementing GFD.8,11 In addition to medical care for patients with CD, the role of the nutritionist is essential in initiating and adhering to implementing GFD. Physicians and pharmacists often fail to check for gluten when prescribing and dispensing medications; yet, it is frequently a component in the solid phase of certain galenic forms. Therefore, these drugs represent a potential source of hidden gluten.12

The aim of this review is to shed light on the diagnostic, nutritional, and medicinal aspects of CD with an emphasis on practical issues in the management of celiac patients.

Epidemiological data

The overall prevalence of CD among the general population varies from region to region; it fluctuates between 0.5% and 1% in Europe and North America,6,13,14 and surprisingly ranges from 2% to 3% in Finland and Sweden.15 High rates are recorded in North Africa, Middle East, and Asia-pacific regions.16 Similarly, the prevalence of the disease is reported to be high in Arab countries, reaching 3.2% in Saudi Arabia, due to dietary habits such as excessive consumption of barley and wheat, and to a higher frequency of DR3-DQ2 haplotypes.17 It is probably underestimated in South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, and is almost unknown in many other countries.18

The disease is more prevalent, with large discrepancies between series in the so called high risk groups, such as type 1 diabetes (1–12%);19,20 auto-immune thyroid disease (2–6%);16,21 Down syndrome (2–6%);22,23 auto-immune hepatitis (3–7%);24,25 Turner syndrome (4–5%);26,27 CD first-degree family members (10–20%);28,29 individuals with iron deficiency anemia (3–15%);29,30 patients with osteoporosis (1–3%),29 and many other clinical conditions.16,28

In addition, The incidence of CD has significantly increased over the past 30 years, from 2–3 to approximately 9–13 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year.31 This likely reflects a fortuitous discovery of non-classic and asymptomatic forms of the disease through serological testing.10,13,29 Indeed, sero-epidemiological studies suggest that for each diagnosed CD case, there could be 3–7 undiagnosed cases.32

Immunopathologic aspects

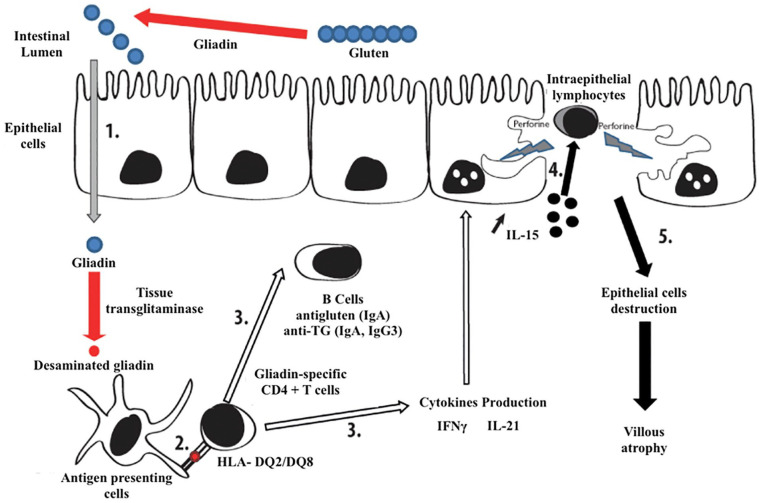

The pathogenic process of CD, as described in Figure 1, takes place in five main steps: (1) the glutamine residues of the ingested gliadin are converted into glutamates by tissue transglutaminase. (2) The modified gliadin is taken up by antigen-presenting cells carrying Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-DQ2 or DQ8, thus activating gliadin-specific CD4+ T cells. (3) These cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-15, IL-21, and interferon-gamma (IFNγ), and allow specific anti-gliadin and anti-transglutaminase responses. (4 and 5) IFNγ and IL-21 induce a massive release of IL-15, which leads to the proliferation and survival of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), the activation of which alters epithelial cells, thus provoking villous atrophy.7,33

Figure 1.

Simplified immunopathological mechanism of celiac disease (adapted from7).

The new face of CD

CD status has gradually changed from a rare enteropathy to a common systemic disease, and as a clinical chameleon, the CD presents in symptomatic, asymptomatic, potential, and refractory forms affecting all age groups.34

In its classic form, the disease usually starts at the age of 6 months, a few weeks after introducing gluten into the diet. It manifests as chronic diarrhea with abundant stools, accompanied by anorexia and apathy. Other clinical symptoms such as recurrent vomiting, anorexia, chronic constipation, growth or puberty delay, short stature, and irritability, are fairly characteristic and require prompt screening for the disease.35 Physical examination often shows abdominal meteorism, signs of undernutrition, loss of muscle and fat tissues, a break in the weight curve, and sometimes, slower growth in height. However, non-classic forms are more frequent than classic ones, with extra-intestinal symptoms (Table 1), thus suggesting CD.36,37 Even obese children may have CD, which undoubtedly contributes to the failure and delay of diagnosis.38

Table 1.

| Digestive disorders | Extra-digestive disorders | Associated pathologies |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic diarrhea Irregular stools Malabsorption Abdominal bloating Chronic constipation (more common in children) Recurrent abdominal pain Irritable bowel syndrome Poor weight gain Decreased appetite Anorexia vomiting Gastro-esophageal reflux |

Refractory iron deficiency anemia Vitamin or mineral deficiencies: Vit B12, Vit B6, Vit D, folate, zinc Hypoplasia of tooth enamel Growth retardation Chronic fatigue Puberty delay Amenorrhea Early menopause Unexplained liver cytolysis Bone pain, Fractures on osteopenia Osteoporosis Recurrent aphthous stomatitis Peripheral neuropathy Ataxia Unexplained hemorrhagic syndrome Herpetiform dermatitis Hyposplenism |

CD in first degree relative Type I diabetes IgA deficiency Sjögren syndrome Autoimmune thyroiditis Autoimmune liver diseases Down syndrome Turner syndrome Williams syndrome CVID (common variable immune deficiency) Neurologic disorders (neuropathy, ataxia, migraine, epilepsy, headache, abnormal EEG*) Sleep disordered breathing |

Electroencephalography abnormalities: spike/sharp wave discharges, especially in the occipital lobes and in the central-temporal sites, and in diffuse distribution.

In adults, most patients with CD do not present with diarrhea, but rather “atypical or extra-intestinal” symptoms such as anemia, osteoporosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, abdominal pain, and neurological disorders.45 Furthermore, in children and adults alike, serological testing should be routinely ordered in the presence of clinical conditions with a high potential for association with CD (Table 1).

The classical forms of CD are characterized by different laboratory findings such as anemia due to iron and/or folate deficiency, hypoprotidemia, hypoalbuminemia, decreased prothrombin time, and vitamin K-dependent factors, and lowered cholesterol mainly related to lipid leakage in the stool.46,47 In fact, biological abnormalities, such as hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia with decreased alkaline phosphatase owing to vitamin D malabsorption, or hypertransaminasemia, may be the only suggestive signs of CD.48–50

Immunoserological tests

Immunoserological tests are excellent diagnostic and monitoring tools for CD; they allow for the identification of patients at risk of developing the disease, better selection of patients requiring intestinal biopsy, and monitoring adherence to GFD.47,49,51 These tests aim to detect auto-antibodies recognizing two main antigens:

- Transglutaminase 2: targeted by anti-tissue transglutaminase 2 (anti-TG2) and anti-endomysium (EmA) Abs, which are very sensitive and specific for CD.51–54

- Gliadin: targeted by the conventional anti-gliadin Abs, which are now obsolete owing to their low sensitivity and specificity. However, Abs against deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP) perform just as well as anti-TG2.55,56

Immunobiological diagnostic approach

In daily practice, when CD is suspected, whether symptomatic or not, or in high-risk individuals, the first line of screening is based on the detection of IgA anti-TG2, followed if positive by EmA, a highly specific marker, which improves the positive predictive value (PPV) of serological tests.57–60 Indeed, the simultaneous positivity of several tests makes the diagnosis of CD very likely.61,62 In addition, a combination of IgA anti-TG2 with IgG anti-TG2 allows the exclusion of CD potentially occulted by IgA deficiency.57,58,63 Additionally, the PPV of these tests in populations at low risk for CD depends on antibody titers. Low titers (less than three times the cut-off) in asymptomatic patients should be retested after 3–6 months under a gluten-rich diet before considering endoscopy and biopsies.2,57 Moreover, the sensitivity of these tests is lower in children under 2 years of age; therefore, besides IgA anti-TG2, IgA DGP testing is recommended for this age group.39,64

As a reproducible, non-invasive, and highly sensitive test, the salivary anti-transglutaminase testing is a promising screening tool for CD.65,66

Notably, serological tests can be falsely negative in certain circumstances as listed in Box 1.

Box 1.

Possible false negative serological tests in celiac disease.39

| • Age <2 years |

| • Selective IgA deficiency |

| • Reduction or elimination of gluten in the diet |

| • Use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents |

| • Possible laboratory error |

Rapid test screening for CD

Physiologically present in the intracellular compartment of erythrocytes,67 TG2 made it possible to develop rapid tests based on a chromatographic method using an endogenous TG obtained from the erythrocytes of patients. However, the performance of the rapid tests remains slightly lower than that of serological tests.68,69 Several studies have demonstrated an interest in rapid tests showing a relatively good correlation with whole blood tests, and good positive and negative predictive values for ambulatory CD screening, particularly in the pediatric population.70 They could, therefore, be used for diagnostic purposes by the physician, even in an office setting.68

Role of the general practitioner in the management of CD

In their daily practice, general practitioners (GP) often encounter patients with CD, regardless of their location. These doctors must rely on specific diagnostic criteria; however, this is difficult because of the wide range of clinical manifestations that patients present with.39

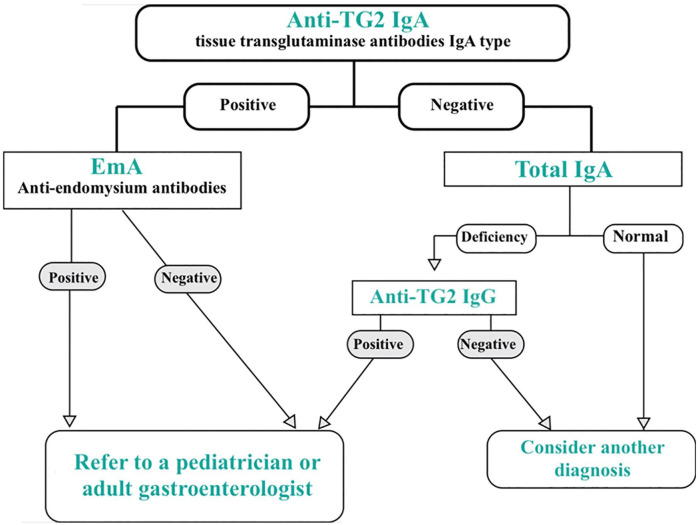

GPs must know which serological screening tests to order, how to interpret the results, and which patients are to be referred to a specialist.39 Thus, according to the diagnostic algorithm proposed in Figure 2, they must refer to a pediatrician or adult gastroenterologist, any patient whose serological tests are positive, for further evaluation.

Figure 2.

Immunoserological diagnosis procedure of CD.

Indeed, the presence of specific antibodies in patients with CD-like symptoms is not sufficient to establish diagnosis owing to many clinical and laboratory circumstances (Box 2) mimicking CD.40,71

Box 2.

| • Anorexia nervosa | • Cystic fibrosis |

| • Autoimmune enteropathies | • Cow’s milk protein intolerance |

| • Intestinal microbial swelling | • Tropical sprue |

| • Collagen sprue | • Whipple’s disease |

| • Crohn’s disease | • Zolliger-Ellison syndrome |

| • Giardiasis | • Eosinophilic gastroenteritis |

| • HIV enteropathy | • Alpha chain disease |

| • Hypogammaglobulinemia | • Graft versus host disease |

| • Infectious gastroenteritis | • Intestinal transplant rejection |

| • Intestinal lymphoma | • Malnutrition |

| • Post-radiation enteritis | • Enteritis (rotavirus, adenovirus, cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, strongyloidosis) |

| • Ischemic enteritis | • Microvillous atrophy |

| • Intestinal tuberculosis | • Epithelial dysplasia |

| • Lactose intolerance | • Abetalipoproteinemia |

| • CVID | • Post-drug enteropathy (ex. Olmesartan) |

| • IgA deficiency |

HLA typing

CD is linked to a strong genetic predisposition, chiefly represented by the HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 systems, which have a high negative predictive value. In fact, less than 1% of patients with CD are negative for both HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, as these are present in approximately 95% and 5% of the cases, respectively, and sometimes both molecules are found in patients.2,72,74 HLA typing cannot be performed as a CD diagnosis tool, since approximately 30–40% of the general population carry HLA-DQ2 and/or DQ8 molecules, and only about 4% of them will develop CD.74–76 On the other hand, HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 typing can be useful when the results of the biopsy are uninformative, or in patients who had initiated GFD on their own prior to serologic testing. CD can also be ruled out in symptomatic patients with negative serological tests as well as in patients considered at high risk, such as first-degree relatives of a patient with CD.74,77

Histopathological diagnosis of CD

Pathologic diagnosis is established or confirmed according to the modified Marsh-Oberhuber and Corazza-Villanacci classifications, with different scales based on the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt hyperplasia, and villous atrophy78,79 (Table 2). The Corazza score has less variability and benefits from more agreement between pathologists.77

Table 2.

Summary of the histological classifications commonly used for CD diagnosis.72

| March modified-Oberhuber | Histological criterion | Corazza-Villanacci | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes* | Crypt hyperplasia | Villous atrophy | ||

| Type 0 | No | No | No | None |

| Type 1 | Yes | No | No | Grade A |

| Type 2 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Type 3a | Yes | Yes | Yes (partial) | Grade B1 |

| Type 3b | Yes | Yes | Yes (subtotal) | |

| Type 3c | Yes | Yes | Yes (total) | Grade B2 |

>40 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 enterocytes for Marsh Modified (Oberhuber).

>25 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 enterocytes for Corazza.

In order to appropriately assess the histological abnormalities of CD according to commonly used criteria, it is recommended to correctly orient the endoscopic sampling (four to six staged biopsies of the bulb and/or the second duodenum) and to repeat levels of biopsy sections. In fact, an imperfectly oriented sample can give a false appearance of villous atrophy (VA).5,80

The major histological criteria of CD include VA of varying degrees with an increased number of IEL. These two signs, although nonspecific, strongly suggest CD and are associated with crypt hyperplasia and increased chorion cell density.81,82 However, VA and increased IEL can be associated with various pathologies, as listed in Box 2.83 In addition, patients with an isolated increase in IEL with positive serological tests are considered as potential candidates for CD as an asymptomatic latent form, while in the majority of cases, the presence of lonely intraepithelial lymphocytosis does not correspond to CD.84

On the other hand, almost all VAs associated with IEL, crypt compensatory hyperplasia, chorion hypercellularity (increased density of inflammatory cells and IgA plasma cells), and positive serological tests, correspond to silent forms of CD.81,85

What can we do without the intestinal biopsy?

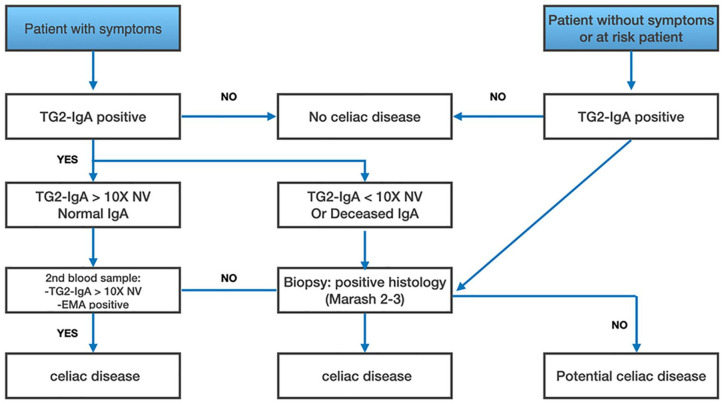

In children with suspected CD, the current trend is the unsystematic use of intestinal biopsy.86 Notably, the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition has proposed a biopsy-free approach in symptomatic children meeting the following four criteria: typical clinical signs, anti-TG2 10-fold or more the upper limit of normal (ULN), positive EmA, and positive HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8.87,88

More recently, a group of experts assume that even asymptomatic children can be accurately diagnosed with CD without biopsy, but only on basis of high titers of IgA anti-TG2 (10-fold or more the ULN), positive EmA tests on 2 blood samples. They also consider that HLA analysis is not required for accurate diagnosis.89 Conversely, intestinal biopsy becomes necessary in the event of clinical manifestations suggestive of CD with negative or discordant serological tests, associated with the positivity of HLA DQ2/8 typing.2,37,90,91 In addition, patients at risk of CD with positive anti-TG2 testing cannot be exempted from the intestinal biopsy.86 In accordance with the above-mentioned guidelines, Husby et al.86 highlighted situations where intestinal biopsy is unnecessary to diagnose CD, particularly in children (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proposal for a CD diagnostic approach to overcome intestinal biopsy in symptomatic children with positive anti-TG2 (TG2-IgA) and EMA testing. In asymptomatic or at-risk children, the positivity of TG2-IgA antibodies should lead to a biopsy and histological analysis. Adapted from.86

In all cases, the decision to perform or not biopsies in this category should be made collegially with the parent (s) and, if applicable, with the child.92

In adults, the positivity of serological tests is insufficient to establish the diagnosis of CD, since false-positive cases are frequent in this group.93 It is, therefore, necessary to complement the serological testing with an intestinal biopsy to confirm the disease before initiating a lifelong GFD.94–96

Diet and gluten-free products

GFD can only be prescribed once the diagnosis of CD has been made with certainty.97 Rigorous adherence to the GFD results in the absence of functional symptoms within a few days and rapid weight gain. The diet also leads to the decrease or even the disappearance of the VA, thus, avoiding the occurrence of complications.97

In general, GFD consists of excluding the four categories of cereals that contain gluten and any food derived from them. Patients with CD must, therefore, systematically exclude bread, pasta, pizza, pies, cakes, and other pastries made from wheat flour as well as industrial food products and preparations, whose composition may contain gluten.98,99 Moreover, patients should be encouraged to consume whole grain gluten-free foods (e.g. quinoa, gluten-free oats, and teff) and avoid gluten-free cereals (e.g. white rice and ground corn).100

The GFD which seems easy in theory, is in fact complicated and difficult to follow, especially in nurseries and schools, restaurants, and even at home.101 Gastroenterologists, pediatricians, and GPs must therefore convince the patient to follow this diet and emphasize the importance of its lifelong compliance.97,98 In this regard, the involvement of the dietitian in the care of patients with CD is fundamental.

When to refer a patient with CD to a dietitian

After confirmation of CD, the clinical conditions listed below (Box 3) require a systematic referral of the patient to an experienced dietitian as part of a collaborative approach.

Box 3.

Clinical conditions justifying the referral of celiac patient to the dietitian.100

| - At the time of diagnosis: initial assessment, followed by 2–3 visits during the first year, then 1–2 annual visits |

| - Suspected gluten exposure (positive serology after 1 or more years of GFD) |

| - Lactose intolerance |

| - Fructose intolerance |

| - Food allergy |

| - Constipation/Diarrhea/Gastroesophageal reflux |

| - Weight fluctuations (gain and loss) |

| - Deficits or toxicity of Micronutrients |

| - Gastroparesis |

| - Hypercholesterolemia |

| - Type 1 diabetes |

| - Refractory celiac disease |

Role of the dietitian in the care of a patient with CD

The initiation of a GFD should preferably be entrusted to an experienced dietitian who is perfectly familiar with this type of diet that requires clear and detailed explanations, with particular attention to its pitfalls.9,100

During the first consultation, the dietitian explains the GFD and insists on the importance of complete and definitive exclusion of gluten from the diet.97,98

The ubiquitous character of gluten in foods requires providing the patients and their families with the most exhaustive possible list of authorized and prohibited foods. Table 3 presents the main categories of foods containing gluten that the dietitian should explain to the celiac patient and/or to his family.

Table 3.

| Food | Allowed | Prohibited |

|---|---|---|

| Milk and dairy products | - Whole milk, semi-skimmed, skimmed, growth milk - Sweetened or unsweetened condensed milk - Fresh, pasteurized, powder, UHT sterilized milk - Goat and sheep milk - Plain fermented milk - Yogurts, flavored white cheeses - Soft, hard, cooked, melted cheeses |

- Flavored milk - Cereal and fiber yogurts and dairy products - Fruit yogurts - Fool Epi Cheese - Industrial milk-based preparations (custards, creams, gelling agents, desserts, foam, etc.) - Mold and spread cheeses - Cereal-based dairy desserts |

| Meats | - All fresh meats, natural frozen, or natural canned - Ground beef “pure beef” |

- Commercial ready-made preparations based on meat or poultry - Breaded, crusted, or flaky preparations |

| Eggs | - All | - Industrial scrambled eggs |

| Fish | - All fresh, smoked, frozen fish, canned fish - Natural crustaceans and mollusks - Fish roe |

- Breaded or floured fish - Commercial preparations based on fish or fish butter - Fish dumplings - Surimi |

| Cold meat | - White ham or country ham - Cooked shoulder - Unbreaded ham - Salted or smoked breast, bacon - Rillettes - Candied and natural foie gras - Plain sausage meat - Sausages from Strasbourg, Morteau, Frankfurt, Montbéliard - Mortadella, head cheese, snout - Andouille and andouillette - Tripe |

- Breaded ham - Meat stuffing - Foams and foie gras cream - Dough and galantine - Pies, sweets, quiches, queen bites - Dry sausages - Garlic sausages, dry sausages, salami, chorizo, cervelas, dumplings - White and Caribbean sausages - Black pudding |

| Cereals and starchy foods | - Rice and rice products: rice cream, pure rice semolina, rice cakes - Corn and derivatives: maizena, semolina - - Cassava and derivatives: tapioca, tapiocaline - Buckwheat and pure buckwheat flour (without wheat flour) - Soy and soy flour - Sorghum - Millet - Sesame - Quinoa - Maranta - Sweet potatoes - Yam - Plantain - Gluten-free infant flour - Certain breakfast cereals made only from rice and/or corn and without malt |

• Wheat or wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelled, kamut, triticale, and their derivatives:

- Flour - Semolina - Pasta, vermicelli, ravioli, gnocchi - Bulgur - Flakes• All types of bread: - White, rye, bran, crumb, brioche, toast, Swedish bread - Rusks, biscotti - Breadcrumbs - Any breaded food• Shortcrust pastry, shortbread, puff pastry, puff pastry • All sweet and savory cakes and cookies: - All aperitif cookies - All products sold in bakeries - All the commercial pastries - All the pastries - Unleavened bread |

| Vegetables and dried vegetables | - Potato and potato starch - All fresh green vegetables, canned or frozen naturally, cooked under a vacuum - All dried vegetables - Small jars of homogenized vegetables mentioned gluten-free |

- All commercial cooked vegetables (canned, frozen, catering) - Soups in sachets or in boxes - Dauphine potatoes, duchess potatoes (check the coating of the hazelnut apples and pre-cooked fries) - Flavored crisps - Instant mashed potato |

| Fruits | - Fresh or natural frozen fruit - Fruits in syrup - Frozen or canned compotes - Chestnuts, natural chestnuts - Oilseeds not dry roasted (nuts, hazelnuts, peanuts, almonds) - Small jars of homogenized fruit without cereals |

- Dried figs (flour that can be used for drying) - Glazed chestnuts and candied fruit (handling possible with floured fingers) - Dry grilled oil seeds |

| Fat | - Oil, butter, fresh cream, Vegetal, margarine, Bacon, bacon, tallow, goose fat | - Wheat germ oil - Low-fat butters or margarines |

| Sweet products | - White sugar, brown sugar, cane, vanilla - Jelly, jam, pure fruit chestnut cream - Honey - Pure, tablet, dark, or milk chocolate - Pure cocoa - Sour candies and lollipops - Pure vanilla extract - Pure licorice |

- Nougat - Sugared - Banania chocolate powder - All loose candy - Eskimos and ice cream in cornet - Packaged candy - Commercial ice creams and sorbets - Filled chocolates - Icing sugar - Chocolate powders |

| Drinks | - Tea, coffee, chicory, infusions - Fruit juice, fruit syrup - Sodas and lemonade |

- Beers (most are made from malt and, therefore, germinated barley) - Plume - Instant drink powders |

| Condiments and various | - Aromatic herbs, pure spices, salt, pepper - Garlic, onion, shallot, pickle - Some mustards - Baker's yeast - Sodium carbonate to replace baking powder |

- Spice mixes - All other commercial condiments and sauces - (Curry, soy sauce, mayonnaise, etc.) - Savora mustard - Baking powder |

At the second consultation (scheduled 1 month after the first), the dietitian will answer questions related to any difficulties the patient may encounter, and ensure that a balanced diet is maintained and the weight is regained. The dietitian must also inquire about the social integration of the patient into the new lifestyle, and about the implementation of meals, particularly in nurseries, schools, and in the workplace.

The following consultations are usually coupled with a medical follow-up of the patient at 3 and 6 months, and then once a year. However, they can be more frequent depending on patient needs.98

To ensure smooth progress of GFD, the dietitian is in charge of educating the patient or his family to:

- 1- Avoid the risk of contamination by gluten-containing products through the following precautions

- Gluten-free products should be meticulously separated from those containing gluten, reserving an appropriate space in the pantry and the refrigerator

- Work surfaces, appliances, toasters or bread makers, cooking utensils, and dishes used to prepare other meals should be thoroughly cleaned before use, or should preferably not be used

2- Read the product labeling carefully:

Patients with CD should be encouraged to routinely read product labels to check for the presence of cereals containing gluten; some ingredients may even change over time. It is also necessary to be vigilant toward foods sold in bulk or catering products.99,103

In addition, terms found on the labels of many products indicate that some ingredients contain gluten and should not be consumed; for example, starch from wheat, barley, rye, or oats; unleavened bread (wheat flour); kamut (ancient wheat), bulgur; malt, and others. A precise list of terms appearing in the composition of a product, which indicate the presence or absence of gluten must also be made available to the patients and their families.4,97,103 A comprehensive list of ingredients and additives that may contain gluten is provided in Table 4, making it easy to identify gluten in food products through their labels.

Table 4.

List of ingredients and names indicating the presence or absence of gluten on product labels.4,103,104

| Presence of gluten | Absence of gluten |

|---|---|

| • Starch from prohibited cereals (wheat, barley, rye, oats) • Starchy material • Vegetable proteins from prohibited cereals • Vegetable protein binder • Malt or malt “extract” • Anti-Caking agents in fruit pastes certain thickeners in light products • Unleavened Bread (wheat flour); wheat, spelled • Kamut (old wheat) • Bulgur • Oatmeal (preparation of cereal grains), vegetable amino acids (without further details) • Gelling agents (without further details) • Plant polypeptides or proteins • Protein binder (without further details) • Triticale (wheat and rye hybrid) |

• Starch from authorized cereals • Flavor of malt • Dextrin • Maltodextrin • Glucose syrup • Glutamate • Gelatin • Lecithin • Plant amino acids • Vegetable protein binders • Thickeners (carob, xanthan gum) • Texturing agents (alginates, carrageenan) |

| Additives which may contain gluten (E1400 to 1451) | All E + 3-digit additives |

| • E1400: Dextrins, roasted starch • E1401: Acid-treated starch • E1402: Starch treated with alkalis • E1403: Bleached starch • E1404: Oxidized starch • E1405: Starches treated with enzymes • E1410: Starch phosphate • E1411: Diamidon glycerol • E1412: Diamidon phosphate • E1413: Phosphate of diamidon phosphate • E1414: Acetylated diamidon phosphate • E1420: Acetylated starch • E1421: Acetylated vinyl acetate starch • E1422: Acetylated diamidon adipate • E1413: Acetylated diamidon glycerol • E1440: Hydroxypropylated starch • E1442: Hydroxypropylateddiamidon phosphate • E1443: Hydroxypropylateddiamidon glycerol |

• E 620 to 625: Glutamate (flavor enhancer) • E 406: Agar agar • E 407: Carrageenans • E 410: Carob seed flour • E 412: Guar gum • E 440a: Pectins • E 460: Cellulose • E 413: Eraser, tragacanth • E 414: Gum arabic • E 415: Xanthan gum • E411: Oat gum (not suitable for gluten intolerant) • All E+3 digits+1 letter additives |

Medical follow-up for patients with CD

A strict follow-up and a multi- disciplinary approach are needed to ensure harmonious growth and prevent CD-related complications.38 As summarized in Table 5, the medical follow-up is generally based on clinical evaluation, serological testing, nutritional assessment, bone density measurement, liver and thyroid exploration, intestinal biopsy and cancer screening.

Table 5.

Guidelines for medical monitoring of patients with celiac disease.40

| Test | Time interval | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation | Annually or if recurring symptoms | |

| Serology | Every 3–6 months until normalization | Normal titers are insensitive to continuous exposure to gluten or enteropathy. The continuous increase in titers indicates significant exposure to gluten. |

| Then every 1–2 years | ||

| Nutritional assessment | Every 3–6 months until normalization | Iron deficiency, 25-OH vitamin D, vitamin B12, folate, and zinc. Monitoring of weight gain, low fiber intake, and constipation. |

| Then every 1–2 years | ||

| Bone density | Once during the first 2 years | Significant increases in bone density are often seen during the first year after diagnosis. Several experts therefore recommend the test 1 year after the GFD. |

| Liver transaminases (ALT/AST) | At the time of diagnosis | Increased levels of ALT and AST are common during celiac disease. Their constant increase indicates an associated hepatic co-morbidity. |

| Then every 1–2 years | ||

| Functional exploration of the thyroid | At the time of diagnosis | Autoimmune thyroiditis is the most common autoimmune disorder found in approximately 15%–20% of celiac adults. |

| Then every 1–2 years | ||

| Intestinal biopsy | To be considered 1–2 years after diagnosis | Repeated biopsies to assess healing are frequently performed. However, their interest remains controversial in celiac patients responding well to GFD with a good clinical course. |

| Cancer screening | As for the general population | Even if the rate of certain cancers is high, they are not frequent enough to justify a specific systematic screening. |

Patients with CD should be examined at least twice during the first year after diagnosis, to monitor clinical and biological manifestations, nutritional status, body mass index (BMI), serological tests, and to assess compliance with GFD.2,72,74 BMI can be a reliable reflection of the impact of GFD on the nutritional status of celiac patients: underweight patients typically gain weight and overweight or obese patients lose weight.38 The efficiency of a GFD is thus attested by clinical and biological improvement (1–3 months), the negativity of specific Ab tests, and the regression of histological abnormalities (12 months).3,105,106 Regular monitoring of serology makes it possible to detect diet deviations, whether voluntary or not; and patients whose serological tests do not improve should be reassessed for continued exposure to gluten.40,72,97

One of the most controversial aspects of CD is the value and the timing of the intestinal biopsy when monitoring the disease. To better appreciate the evolution of intestinal damage, a biopsy is generally recommended 1–2 years after GFD initiation. However, intestinal healing is often slow, incomplete, and age-dependent.70,107 Moreover, intestinal biopsy remains essential if symptoms persist.70

In general, the management of CD must include a nutritional assessment in order to detect deficiencies such as autoimmune thyroiditis (T3, T4, TSH, anti-thyroperoxidase, and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies) and justify replacement therapy (hemoglobin, albumin, calcium, folate, vitamin B12, zinc, magnesium, and vitamin D).9

It is also recommended to evaluate bone mineral density during the first year of follow-up, using densitometry.9,72

In the pediatric population, the late childhood is particularly critical for the conduct of GFD. In fact, this diet impacts daily life and can be a source of frustration or even depression, and often experienced as “dissocializing,” especially among adolescents.101,108 Closer follow-up by both the specialist and the dietitian is, therefore, necessary to re-explain the disease and its complications, to understand the difficulties of the adolescent in accepting the diet, and to help them overcome social or academic constraints, thus, preventing potential abandonment of the diet.109

On the other hand, the transition to adulthood is often a period of slackening during follow-up, and sometimes of GFD. Consequently, the orientation toward the adult specialist becomes necessary to ensure continuity in care and avoid the insidious installation of serious complications, mainly, osteopenia and fracture osteoporosis, increased risk of autoimmune diseases (type I diabetes, thyroiditis, and others), hypofertility, or even sterility, neuropathies, and particularly the risk of cancers such as adenocarcinomas and intestinal lymphomas.3,11,108

Medicines are a potential source of gluten concealment, which is commonly introduced into the solid phase of drugs such as tablets and pills when the starch used is extracted from wheat, rye, and/or barley, serving as a diluent or binder.12,103 Starch is also used as a carrier for controlled or sustained-release dosage forms as well as to form nanoparticles, nanogels, and microcapsules.110 The excipients of some drugs may also contain gluten in small quantities, especially those based on wheat starch, wheat germ oil, wheat bran, wheat flour, barley bran, and vegetable amylase, which can be extracted from barley.104 The type of excipients can also be different between generic and branded drugs, and those with a known effect (lactose and gluten) must be indicated in the leaflet intended for patients.111 Thus, even if the brand name is determined to be gluten-free, the gluten-free status of each generic must be verified by the pharmacist and the celiac patient as well.

Unfortunately, drug manufacturers may not disclose the source of the starch used or indicate whether their products are free from gluten contamination.12 Indeed, all medicines can be made gluten-free since alternatives to starch can be used during production. This highlights the importance of adopting a new policy for the manufacture of gluten-free drugs by pharmaceutical companies and excipient producers.12

Since 2017, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a draft guidance on Gluten in Drug Products and Associated Labeling, recommending to drug manufacturers a statement to include in their labeling when truthful and properly supported: “Contains no ingredient made from a gluten-containing grain (wheat, barley, or rye)”.112

Hence, the pharmacist has an essential role in the management of gluten-intolerant patients. He must check whether the medicine contains gluten, even in very small quantities, especially in excipients. The following components indicate the presence of gluten in the drug: starch, glycerol starch, starch glycolate, carboxymethyl starch, partial hydrolysate of hydrogenated starch, modified/soluble/pregelatinized starch, precooked/processed wheat germ oil, wheat bran, barley, and vegetable amylase. An exception is made for the specialties of Maxilase® or Megamylase® (possibly extracted from barley), which have been authorized by the French association of gluten intolerants after investigations in pharmaceutical laboratories.113 Box 4 reports a non-exhaustive list of medications containing gluten, drawn from the Vidal dictionary, indicating both the generic and the brand name. A complementary list of drugs that may or may not contain gluten depending on the concentration and formulation of the drug is displayed in Table 6. Indeed, the generic name of drugs may differ depending on the country of origin and distribution. These lists must also be regularly updated with the development of new generic drugs. Thus, both pharmacists and patients with CD should constantly check the composition of the drugs.113 Determining the gluten status of generic drugs is challenging owing to changes in manufacturers, drug shortages, and wholesale product variability. These factors make identifying the gluten content in generic medications difficult, even for the manufacturers themselves.114 Additionally, even low gluten intake can irritate sensitive individuals.104 In contrast, the ointment forms, effervescent tablets, drinkable drops, oral solutions, eye drops, suppositories, nasal drops, and injectable ampoules are gluten-free regardless of the specialty name.113 Some medications are the only ones to contain the active principle, and the benefit/risk ratio of these drugs must therefore be evaluated by the prescriber before use or exclusion in any therapy.104,114

Box 4.

Pharmaceutical specialties containing gluten or marked “wheat starch” in their composition.104,113 (Brand names of drugs are put between brackets).

| • ABUFENE (Beta-alanine) 400 mg tablet • ACEBUTOLOL WINTHROP (acebutolol) 200 mg coated tablet • ACEBUTOLOL ZENTIVA (acebutolol) 400 mg coated tablet • ADENYL (Adenosine phosphate) 60 mg tablet • ADIAZINE (Sulfadiazine) 500 mg tablet • ALFATIL (Céfaclor) 250 mg/5 ml powder for oral suspension • ALLOPURINOL ARROW (allopurinol) 100 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL ARROW (allopurinol) 200 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL ARROW (allopurinol) 300 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL EG (allopurinol) 100 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL EG (allopurinol) 200 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL EG (allopurinol) 300 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL SANDOZ (allopurinol) 100 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL SANDOZ (allopurinol) 200 mg tablet • ALLOPURINOL SANDOZ (allopurinol) 300 mg tablet • APAROXAL (phenobarbital) 100 mg tablet • ARTANE (trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride) 2 mg tablet • ARTANE (trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride) 5 mg tablet • ARTICHAUD BOIRON (Cynara scolymus) capsule • ATHYMIL (mianserin hydrochloride)10 mg coated tablet • ATHYMIL (mianserin hydrochloride) 30 mg coated tablet • ATHYMIL (mianserin hydrochloride) 60 mg coated tablet • ASPIRINE RICHARD (aspirin) 500 mg tablet • BECILAN (pyridoxine hydrochloride) 250 mg coated tablet • BELUSTINE (lomustine) 40 mg capsule • BENEMIDE (probenecid)500 mg tablet • BEVITINE (thiamine hydrochloride) 250 mg coated tablet • BI-PROFENID LP (ketoprofen) 100 `mg tablet • BOURDAINE BOIRON (frangula alnus) capsule • BUFLOMEDIL ARROW (buflomedil) 150 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL ARROW (buflomedil) 300 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL EG (buflomedil) 150 mg coated tablet • BUFLOMEDIL EG (buflomedil) 300 mg coated tablet • BUFLOMEDIL GNR (buflomedil) 150 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL GNR (buflomedil) 300 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL IREX (buflomedil) 150 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL IREX (buflomedil) 300 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL RPG (buflomedil) 150 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL RPG (buflomedil) 300 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL RATIOPHARMA (buflomedil) • BUFLOMEDIL TEVA (buflomedil) 150 mg coated tablet • BUFLOMEDIL TEVA (buflomedil) 300 mg tablet • BUFLOMEDIL ZYDUS (buflomedil) 150 mg tablet • CANTABILINE (hymecromone) 400 mg tablet • CERIS (trospium chloride) 20 mg coated tablet • CASSIS BOIRON (ribes nigrum) capsule • CLARITHROMYCINE SANDOZ (clarithromycin) 50 mg/ml powder for oral suspension • CHLORHYDRATE D'HEPTAMINOL RICHARD (Heptaminol hydrochloride) 187.8 mg tablet • CIRKAN (Hesperidin Methyl Chalcone) coated tablet • COLIMYCINE (colistimethate sodium) 1.5 M UI tablet • CYNOMEL (liothyronine sodium) 25 µg tablet • DANTRIUM (dantrolene sodium) 100 mg capsule • DANTRIUM (dantrolene sodium) 25 mg capsule • DENSICAL VITAMINE D3 (cholecalciferol) powder for oral suspension • DESINTEX (sodium thiosulphate) coated tablet • DEXAMBUTOL (ethambutol) 500 mg coated tablet |

| • DIAMOX (acetazolamide) 250 mg tablet • DICYNONE (tranexamic acid) 500 mg tablet • DI-HYDAN (phenytoin sodium) 100 mg tablet |

| • DISULONE (dapsone) tablet • DOLIPRANE LIB (paracetamol) 500 mg tablet • DOLIRHUME (paracetamol + pseudoephedrine) 500 mg/30 mg tablet • DOLIRHUMEPRO (paracetamol, pseudoephedrine & doxylamine) tablet • DOXYLAMINE (doxylamine) tablet • ENTECET (germinated barley + amylase) coated tablet • ENTEROPATHYL (sulfaguanidine) 500 MG • ENZYMICINE (Neomycin) cone for dental use • ESIDREX (hydrochlorothiazide) 25 mg tablet • EXACYL (tranexamic acid) 500 mg coated tablet • FAGOPYRUM ESCULENTUM • FLAGYL (metronidazole) 250 mg coated tablet • FLAGYL (metronidazole) 500 mg coated tablet • FURADANTINE (nitrofurantoin) 50 mg capsule • FURADOINE (nitrofurantoin) 50 mg tablet • GARDENAL (phenobarbital) 10 mg tablet • GARDENAL (phenobarbital) 50 mg tablet • GARDENAL (phenobarbital) 100 mg tablet • GINSENG BOIRON (ginseng) capsule • GLUTAMINOL B6 (glutamic acid + Pyroxidine) tablet • HEPTAMYL 187.8 (heptaminol) mg tablet • HEXASTAT (altrétamine) 100 mg capsule • IMOVANE (zopiclone) 3.75 mg coated tablet • IMOVANE (zopiclone) 7.5 mg coated tablet • INSADOL (corn) 35 mg coated tablet • ISOPRINOSINE (inosine acedoben dimepranol) 500 mg tablet • KETOPROFENE ZENTIVA LP (ketoprefen) 100 mg tablet • LARGACTIL (chlorpromazine hydrochloride) 100 mg coated tablet • LARGACTIL (chlorpromazine hydrochloride) 25 mg coated tablet • LEGALON (silymarin) 70 mg coated tablet • LIORESAL (baclofen) 10 mg coated tablet • MALOCIDE (pyriméthamine) 50 mg tablet • MEGAMAG (magnesium) 45 mg capsule • MEPROBAMATE RICHARD (meprobamate) 400 mg tablet • METHOTREXATE BELLON (methotrexate) 2.5 mg tablet • MODUCREN (timolol maleate + amiloride chlorhydrate + hydrochlorothiazide) tablet • MUCITUX (eprazinone dihydrochloride) 50 mg coated tablet • NEO-CODION (codeine) coated tablet • NEOCONES (neomycin sulfate + benzocaine) cone for dental use • NEULEPTIL (propériciazine) 25 mg coated tablet • NIVAQUINE (Chloroquine) 100 mg tablet • NORDAZ (Nordazepam) 15 mg tablet • NORDAZ (Nordazepam) 7.5 mg tablet • NOTEZINE (diethylcarbamazine) 100 mg tablet • NOZINAN (levomepromazine) 100 mg coated tablet • NOZINAN (levomepromazine) 25 mg coated tablet |

| • PARACETAMOL SANDOZ (paracetamol) 1 g tablet • PARACETAMOL SANDOZ (paracetamol) 500 mg tablet • PARACETAMOL ZYDUS (paracetamol) 500 mg tablet • PASSIFLORE BOIRON (passiflora) capsule • PEFLACINE (pefloxacin) 400 mg coated tablet • PEFLACINE MONODOSE (pefloxacin) 400 mg coated tablet • PERUBORE INHALATION (plant essences) inhalation tablet • PHENERGAN (promethazine) 25 mg coated tablet • PHOLCODYL (pholcodine) liquid mixture • PIPORTIL (pipotiazine) 10 mg coated tablet • PIPRAM FORT (piperacillin + tazonactum) 400 mg coated tablet • PRAZINIL (carpipramine) 50 mg coated tablet • PREVISCAN (fluindione) 20 mg tablet • PROFEMIGR (ketoporofen) 150 mg tablet |

| • PYOREX (sodium ricinoleate + thacridine) toothpaste • PYOSTACINE (pyostacine) 250 mg coated tablet • PYOSTACINE (pyostacine) 500 mg coated tablet • QUININE CHLORHYDRATE LAFRAN (quinine) 224.75 mg tablet • QUININE CHLORHYDRATE LAFRAN (quinine) 449.50 mg tablet • QUININE SULFATE LAFRAN (quinine) 217.2 mg tablet • QUININE SULFATE LAFRAN (quinine) 434.4 mg tablet • RASILEZ HCT (hydrochlorothiazide) 150 mg/12.5 mg coated tablet • RASILEZ HCT (hydrochlorothiazide) 300 mg/12.5 mg coated tablet • RASILEZ HCT (hydrochlorothiazide) 300 mg/25 mg coated tablet • REINE DES PRES BOIRON (spiraea ulmaria) capsule • RHUMAGRIP (acetaminophen + pseudoephedrine) tablet • RITALINE (methylphenidate) 10 mg tablet • RUBOZINC (zinc) 15 mg capsule • SECTRAL (acebutolol) 200 mg coated tablet • SECTRAL (acebutolol) 400 mg coated tablet • SPASFON (phloroglucinol) coated tablet • SPOTOF (tranexamic acid) 500 mg coated tablet • SULFARLEM (anetholtrithione) 12.5 mg coated tablet • SULFARLEM S (anetholtrithione) 25 mg coated tablet • SURMONTIL (trimipramine) 100 mg coated tablet • SURMONTIL (trimipramine) 25 mg tablet • TANGANIL (acetylleucine) 500 mg tablet • TARDYFERON B9 (iron + folic acid) coated tablet • TARDYFERON B9 (iron + folic acid) coated tablet • TERALITHE (lithium) 250 mg tablet • TERCIAN (cyamemazine) 100 mg coated tablet • TERCIAN (cyamemazine) 25 mg coated tablet • TERGYNAN (metronidazole + neomycin sulfate + nystatin) vaginal tablet • THERALENE (ternidazole + neomycin sulfate + nystatin) coated tablet • TONILAX (frangula alnus) coated tablet • TOPREC (ketoprofen) 25 mg tablet • TRIHEXY RICHARD (trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride) 2 mg tablet • TRIHEXY RICHARD (trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride) 5 mg tablet • TRIMEBUTINE BIOGARAN (trimebutine) 100 mg tablet • TRIMEBUTINE MERCK (trimebutine) 100 mg tablet • TRIMEBUTINE MYLAN (trimebutine) 100 mg tablet • TRIMEBUTINE QUALIMED (trimebutine) 100 mg tablet • TRINITRINE SIMPLE LALEUF (nitroglycerin) 0.15 mg coated pill • VIBTIL (dry extract of lime sapwood) 250 mg coated tablet • VISCERALGINE (tiemonium Iodide) 50 mg coated tablet • VITAMINE B6 RICHARD (piroxidin) 250 mg tablet • VITATHION (ascorbic acid + thiamine + inositocalcium) effervescent granule • VOGALENE (metopimazine) 15 mg capsule • ZOPICLONE ZENTIVA or RPG (zopiclone) 7.5 mg coated tablet |

Table 6.

Gluten status of medications (adapted from114).

| Drug (Manufacturer) | Strength and formulation | Gluten status |

|---|---|---|

| - Allopurinol (Mylan) - Amino acid solution (B. Braun) - Azacitadine (Celgene) - Barium sulfate contrast dye (EZ EM CANADA) - Dextrose solution (Hospira) - Diphenoxylate /atropine (Mylan) - Doxycycline hyclate (Mylan) - Endure handsoap (Ecolab) |

- 300 mg tablet - 10% and 15% injections - 100 mg injection - 9.5 g in 23.5 g suspension - 5% injection - 2.5 mg/0.025 mg tablet - 100 mg tablet - Not applicable |

- Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free |

| - Levocetirizine (Dr. Reddy’s) - Linezolid (Pfizer) - Lipid emulsion (Fresenius kabi) - Loperamide (Mylan) - Losartan (Mylan) - Magnesium oxide (McKesson Packaging) - Menthol/camphor (Geritrex) - Metaxalone (Amneal) - Morphine (Hospira) - Pomalidomide (Celgene) - Prochlorperazine (Mylan) - Rosuvastatin (AstraZeneca) - Salsalate(Amneal) - Acetaminophen (McNeil) - Acetaminophen (McNeil) - Acyclovir (Teva) - Acyclovir (Teva) - Allopurinol (Watson) - Amlodipine (Teva) - Amoxicillin (Sandoz) - Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Sandoz) - Apixaban (Bristol-Meyers Squibb) - Aripiprazole (Otsuka) - Atazanavir (Bristol-Meyers Squibb) - Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine (Qualitest) - Celecoxib (Pfizer) - Cephalexin (Teva) - Ciprofloxacin (Watson) - Clindamycin (Watson) - Dabigatran (BoehringerIngelheim) - Darunavir (Janssen) - Darunavir (Janssen) - Dextran/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (Alcon) - Diphenhydramine (Major) - Diphenhydramine (Qualitest) - Diphenoxylate/atropine (Greenstone) - Emtricitabine/tenofovir (Gilead) - Ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel (Watson) - Ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone (Watson) - Ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate (Janssen) - Ethinyl estradiol/norgestimate (Watson) - Ethinyl estradiol/norgestrel (Watson) - Etravirine (Janssen) - Fluconazole (Teva) - Hydrocortisone cream (Fougera) - Hydrocortisone cream (Wyeth) - Hydrocortisone sodium succinate (Pfizer) - Intravenous immune globulin (CSL Behring) - Levofloxacin (Lupin) - Linezolid (Pfizer) - Lopinavir/ritonavir (AbbVie) - Lopinavir/ritonavir (AbbVie) - Magnesiumtrisalicylate (Silarx) - Maraviroc (ViiV Healthcare) - Multivitamin with fluoride (Qualitest) - Nimodipine (Arbor) |

- 5 mg tablet - 100 g/5 mL suspension- 10%, 20%, and 30% injections - 2 mg capsule - 25 and 50 mg tablets - 400 mg tablet - 0.5%/0.5% lotion - 800 mg tablet - 2 and 4 mg injections - 1, 2, 3, and 4 mg capsules - 5 mg tablet - 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg tablets - 500 and 750 mg tablets - 325 mg tablet - 500 mg caplet - 200 mg capsule - 400 mg tablet - 300 mg tablet - 5 mg tablet - 400 mg/5 mL suspension - 500 and 875 mg tablets - 2.5 and 5 mg tablets - 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 mg tablets - 150, 200, and 300 mg capsules - 325 mg/50 mg/40 mg tablet - 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg capsules - 500 mg capsule - 250 and 500 mg tablets - 150 mg capsule - 75 and 150 mg capsules - 75, 150, 400, 600, and 800 mg tablets - 100 mg/mL suspension - 0.1%/ 0.3% ophthalmic solution - 25 and 50 mg tablets - 12.5 mg/5 mL liquid - 2.5 mg/0.02 mg tablet - 200 mg/300 mg tablet - 0.03 mg/0.15 mg tablet - 0.035 mg/1 mg tablet - Varies - Varies - 0.03 mg/0.3 mg tablet - 25, 100, and 200 mg tablets - 400 mg tablet - 0.5% cream - 1% cream - 100 mg injection - 3, 6, and 12 g injections - 250 and 500 mg tablets - 600 mg tablet - 100 mg/25 mg and 200 mg/50 mg - 80 mg/20 mg/mL solution - 500 mg solution - 150 and 300 mg tablets - 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg chewable tablets - 3 mg/mL solution |

- Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Gluten free - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten |

| - Oxycodone immediate release (Actavis) - Pantoprazole (Dr. Reddy’s) - Potassium chloride (Upsher-Smith) - Rabeprazole (Eisai) - Ritonavir (AbbVie) - Ritonavir (AbbVie) - Ritonavir (AbbVie) - Rivaroxaban (Janssen) - Saquinavir (Genentech) - Sitagliptin (Merck) - Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim DS (Amneal) - Telmisartan (BoehringerIngelheim) - Tramadol (Mylan) - Triazolam (Greenstone) - Valsartan (Novartis) - Vancomycin (Baxter) - Nebivolol (Forest) - Tramadol (Amneal) |

- 15 and 30 mg tablets - 20 and 40 mg tablets - 20 meq tablet - 20 mg tablet - 100 mg tablet - 100 mg tablet - 80 mg/mL solution - 10, 15, and 20 mg tablets - 200 and 500 mg capsules - 25, 50, and 100 mg tablets - 800 mg/160 mg tablet - 20, 40, and 80 mg tablets - 50 mg tablet - 0.125 and 0.25 mg tablets - 40, 80, 160, and 320 mg tablets - 1 g injection - 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg tablets - 50 mg tablet |

- Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Possibly contains gluten - Contains gluten - Contains gluten |

To sum up, this overview suggested an integrated approach to the main practical aspects of CD (clinical and laboratory diagnosis; implementation and monitoring of gluten-free diet; delivering and use of gluten-free medications), which represent concerns for physicians, biologists, nutritionists and pharmacists during the process of CD management. However, as limitations, some aspects have not been or insufficiently developed, such as the role of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of CD, the comparative performance of serological testing, the seronegative and refractory CD and possible immunotherapeutic approaches. We have also been faced to the scarcity of scientific data related to drugs and gluten.

Conclusion

Despite its polymorphism with many differential diagnoses, CD benefits from a standardized diagnostic approach based on serology, intestinal biopsy, and possibly HLA typing. The management of CD is a multidisciplinary concern, involving general practitioners, different clinical and biological specialists, as well as dietitians and pharmacists.

The implementation and monitoring of GFD remains a challenge, which reflects the incontestable role of the dietitian as well as that of the pharmacist, considering the risk of the existence or concealment of gluten in the various stages of drug manufacturing.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Brahim Admou  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3255-8220

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3255-8220

References

- 1. Roujon P, Sarrat A, Contin-Bordes C, et al. (2013) Diagnostic sérologique de la maladie cœliaque. Pathologie Biologie 61: e39–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, et al. (2012) European society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 54: 136–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malamut G, Cellier C. (2010) Celiac disease. La Revue de Médecine Interne 31: 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tounian P, Sarrio F. (2011) Prise en charge diététique de certaines pathologies. In: Masson E. (ed.) Alimentation De L’enfant De 0 à 3 Ans. Collection Pédiatrie au Quotidien, Elsevier, pp.73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruneau J, Cheminant M, Khater S, et al. (2018) Importance of histopathology in coeliac disease diagnosis and complications. Revue Francophone des Laboratoires 2018: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fasano A, Catassi C. (2012) Clinical practice. Celiac disease. The New England Journal of Medicine 367: 2419–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Godat S, Velin D, Aubert V, et al. (2013) An update on celiac disease. Revue Médicale Suisse 9: 1584–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malamut G, Verkarre V, Suarez F, et al. (2010) The enteropathy associated with common variable immunodeficiency: The delineated frontiers with celiac disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 105: 2262–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lepers S, Couignoux S, Colombel J-F, et al. (2004) La maladie cœliaque de l’adulte : Aspects nouveaux. La Revue de Médecine Interne 25: 22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riznik P, De Leo L, Dolinsek J, et al. (2021) Clinical presentation in children with coeliac disease in Central Europe. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 72(4): 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I. (2013) Complications of celiac disease. Pathologie Biologie 61: e21–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shah AV, Serajuddin ATM, Mangione RA. (2018) Making all medications gluten free. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 107: 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nenna R, Tiberti C, Petrarca L, et al. (2013) The celiac iceberg: Characterization of the disease in primary schoolchildren. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 56: 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. (2018) Coeliac disease. Lancet 391: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. (2010) The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: Results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Annals of Medicine 42: 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashtari S, Najafimehr H, Pourhoseingholi MA, et al. (2021) Prevalence of celiac disease in low and high risk population in Asia–Pacific region: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 11: 2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Metwally A, Toivola P, AlAhmary K, et al. (2020) The epidemiology of celiac disease in the general population and high-risk groups in Arab Countries: A systematic review. BioMed Research International 2020: 6865917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gujral N, Freeman HJ, Thomson ABR. (2012) Celiac disease: Prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology 18: 6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costa Gomes R, Cerqueira Maia J, Fernando Arrais R, et al. (2016) The celiac iceberg: From the clinical spectrum to serology and histopathology in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and Down syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 51: 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oujamaa I, Sebbani M, Elmoumou L, et al. (2019) The prevalence of celiac disease-specific auto-antibodies in type 1 diabetes in a Moroccan population. International Journal of Endocrinology 2019: 7895207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minelli R, Gaiani F, Kayali S, et al. (2018) Thyroid and celiac disease in pediatric age: A literature review. Acta Biomedica 89: 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Du Y, Shan L-F, Cao Z-Z, et al. (2018) Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with Down syndrome: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 9: 5387–5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pavlovic M, Berenji K, Bukurov M. (2017) Screening of celiac disease in Down syndrome-old and new dilemmas. World Journal of Clinical Cases 5: 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoffmanová I, Sánchez D, Tučková L, et al. (2018) Celiac disease and liver disorders: From putative pathogenesis to clinical implications. Nutrients 10: 892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Najafi M, Sadjadei N, Eftekhari K, et al. (2014) Prevalence of celiac disease in children with autoimmune hepatitis and vice versa. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics 24: 723–728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Sanctis V, Khater D. (2019) Autoimmune diseases in Turner syndrome: An overview. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis 90: 341–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kılınç S. (2019) Associated clinical abnormalities among patients with Turner syndrome. Nothern Clinics Of Istanbul 7: 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumral D, Syed S. (2020) Celiac disease screening for high-risk groups: Are we doing it right? Digestive Diseases and Sciences 65(8): 2187–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dubé C, Rostom A, Sy R, et al. (2005) The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: A systematic review. Gastroenterology 128: S57–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mahadev S, Laszkowska M, Sundström J, et al. (2018) Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with iron deficiency anemia—A systematic review with meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 155: 374–382.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, et al. (2007) Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 26: 1217–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rewers M. (2005) Epidemiology of celiac disease: What are the prevalence, incidence, and progression of celiac disease? Gastroenterology 128: S47–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ettersperger J, Montcuquet N, Malamut G, et al. (2016) Interleukin-15-dependent T-cell-like innate intraepithelial lymphocytes develop in the intestine and transform into lymphomas in celiac disease. Immunity 45: 610–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rampertab SD, Pooran N, Brar P, et al. (2006) Trends in the presentation of celiac disease. The American Journal of Medicine 119: 355.e9–355.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, et al. (2005) Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 40: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mouterde O, Hariz MB, Dumant C. (2008) Le nouveau visage de la maladie cœliaque. Archives de Pédiatrie 15: 501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fasano A. (2005) Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric population. Gastroenterology 128: S68–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nenna R, Mosca A, Mennini M, et al. (2015) Coeliac disease screening among a large cohort of overweight/obese children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 60: 405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rashid M, Lee J. (2016) Serologic testing in celiac disease: Practical guide for clinicians. Canadian Family Physician 62: 38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kelly CP, Bai JC, Liu E, et al. (2015) Advances in diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 148: 1175–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nion-Larmurier I, Cosnes J. (2009) Celiac disease. Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique 33: 508–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bushara KO. (2005) Neurologic presentation of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 128: S92–S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nenna R, Petrarca L, Verdecchia P, et al. (2016) Celiac disease in a large cohort of children and adolescents with recurrent headache: A retrospective study. Digestive and Liver Disease 48: 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parisi P, Pietropaoli N, Ferretti A, et al. (2015) Role of the gluten-free diet on neurological-EEG findings and sleep disordered breathing in children with celiac disease. Seizure 25: 181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF, Green PHR. (2015) Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ 351: h3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ehsani-Ardakani MJ, Nejad MR, Villanacci V, et al. (2013) Gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal presentation in patients with celiac disease. Archives of Iranian Medicine 16: 78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Olives JP. (2001) Nouvelles stratégies diagnostiques de la maladie cœliaque. Archives de Pédiatrie 8: 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vajro P, Maddaluno S, Veropalumbo C. (2013) Persistent hypertransaminasemia in asymptomatic children: A stepwise approach. World Journal of Gastroenterology 19: 2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sharma M, Singh P, Agnihotri A, et al. (2013) Celiac disease: A disease with varied manifestations in adults and adolescents. Journal of Digestive Diseases 14: 518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Admou B, Essaadouni L, Krati K, et al. (2012) Atypical celiac disease: From recognizing to managing. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2012: 637187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hill ID. (2005) What are the sensitivity and specificity of serologic tests for celiac disease? Do sensitivity and specificity vary in different populations? Gastroenterology 128: S25–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bai JC, Fried M, Corazza GR, et al. (2013) World Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines on celiac disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 47: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bossuyt X. (2014) Le diagnostic de la maladie cœliaque au laboratoire: Recommandations actuelles. Revue Francophone des Laboratoires 2014: 15–20.32288817 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Meensel B, Hiele M, Hoffman I, et al. (2004) Diagnostic accuracy of ten second-generation (human) tissue transglutaminase antibody assays in celiac disease. Clinical Chemistry 50: 2150–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Volta U, Granito A, Parisi C, et al. (2010) Deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies as a routine test for celiac disease: A prospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 44: 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Agardh D. (2007) Antibodies against synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides and tissue transglutaminase for the identification of childhood celiac disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 11: 1276–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Webb C, Norström F, Myléus A, et al. (2015) Celiac disease can be predicted by high levels of anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in population-based screening. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 60: 787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sandström O, Rosén A, Lagerqvist C, et al. (2013) Transglutaminase IgA antibodies in a celiac disease mass screening and the role of HLA-DQ genotyping and endomysial antibodies in sequential testing. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 57: 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, et al. (2005) The diagnostic accuracy of serologic tests for celiac disease: A systematic review. Gastroenterology 128: S38–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Giersiepen K, Lelgemann M, Stuhldreher N, et al. (2012) Accuracy of diagnostic antibody tests for coeliac disease in children: Summary of an evidence report. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 54: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sugai E, Hwang HJ, Vázquez H, et al. (2015) Should ESPGHAN guidelines for serologic diagnosis of celiac disease be used in adults? A prospective analysis in an adult patient cohort with high pretest probability. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 110: 1504–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oyaert M, Vermeersch P, De Hertogh G, et al. (2015) Combining antibody tests and taking into account antibody levels improves serologic diagnosis of celiac disease. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine 53: 1537–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rashtak S, Ettore MW, Homburger HA, et al. (2008) Combination testing for antibodies in the diagnosis of coeliac disease: Comparison of multiplex immunoassay and ELISA methods. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 28: 805–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hoerter NA, Shannahan SE, Suarez J, et al. (2017) Diagnostic yield of isolated deamidated gliadin peptide antibody elevation for celiac disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 62: 1272–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Condò R, Costacurta M, Docimo R. (2013) The anti-transglutaminase auto-antibodies in children’s saliva with a suspect coeliac disease: Clinical study. ORAL & implantology 6: 48–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bonamico M, Nenna R, Montuori M, et al. (2011) First salivary screening of celiac disease by detection of anti-transglutaminase autoantibody radioimmunoassay in 5000 Italian primary schoolchildren. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 52: 17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bergamini CM, Dean M, Matteucci G, et al. (1999) Conformational stability of human erythrocyte transglutaminase. Patterns of thermal unfolding at acid and alkaline pH. European Journal of Biochemistry 266: 575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Korponay-Szabo I, Nemes E, Vecsei Z, et al. (2008) Rapid bedside detection of humoral IgA deficiency and celiac disease antibodies from capillary blood. In: 2008 World congress of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition,Chutes d’Iguazu, Brésil, 16–20, Bologna: Medimond Iternational Proceedings, https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Documents/WorldCongress2008abstracts.pdf

- 69. Raivio T, Kaukinen K, Nemes É, et al. (2006) Self transglutaminase-based rapid coeliac disease antibody detection by a lateral flow method. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 24: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Costa S, Astarita L, Ben-Hariz M, et al. (2014) A point-of-care test for facing the burden of undiagnosed celiac disease in the Mediterranean area: A pragmatic design study. BMC Gastroenterology 14: 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. da Silva TSG, Furlanetto TW. (2010) Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira 56: 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al. (2013) ACG clinical guidelines: Diagnosis and management of celiac disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 108: 656–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ramos ATP, Figueirêdo MM, de Aguiar APB, et al. (2016) Celiac disease and cystic fibrosis: Challenges to differential diagnosis. Folia Medica (Plovdiv) 58: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, et al. (2014) Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British society of gastroenterology. Gut 63: 1210–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB, et al. (2011) Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annual Review of Immunology 29: 493–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. (2006) American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 131: 1981–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shannahan S, Leffler DA. (2017) Diagnosis and updates in celiac disease. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 27: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McCarty TR, O’Brien CR, Gremida A, et al. (2018) Efficacy of duodenal bulb biopsy for diagnosis of celiac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy International Open 6: E1369–E1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Adelman DC, Murray J, Wu T-T, et al. (2018) Measuring change in small intestinal histology in patients with celiac disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 113: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pais WP, Duerksen DR, Pettigrew NM, et al. (2008) How many duodenal biopsy specimens are required to make a diagnosis of celiac disease? Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 67: 1082–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Verkarre V, Brousse N. (2013) Le diagnostic histologique de la maladie cœliaque. Pathologie Biologie 61: e13–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Patey-Mariaud De, Serre N, Verkarre V, Cellier C, et al. (2001) Etiological diagnosis of villous atrophy. Annales de Pathologie 939: 301–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pallav K, Leffler DA, Tariq S, et al. (2012) Noncoeliac enteropathy: The differential diagnosis of villous atrophy in contemporary clinical practice. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 35: 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Aziz I, Key T, Goodwin JG, et al. (2015) Predictors for celiac disease in adult cases of duodenal intraepithelial lymphocytosis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 49: 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schmitz J, Garnier-Lengliné H. (2008) Celiac disease diagnosis in 2008. Archives de Pédiatrie 15: 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. (2019) AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—Changing utility of serology and histologic measures: Expert review. Gastroenterology 156: 885–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bouteloup C. (2016) Digestive diseases related to wheat or gluten: Certainties and doubts. Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 51: 248–258. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Catassi C, Fasano A. (2010) Celiac disease diagnosis: Simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. The American Journal of Medicine 123: 691–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Werkstetter KJ, Korponay-Szabó IR, Popp A, et al. (2017) Accuracy in diagnosis of celiac disease without biopsies in clinical practice. Gastroenterology 153: 924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gidrewicz D, Potter K, Trevenen CL, et al. (2015) Evaluation of the ESPGHAN celiac guidelines in a North American pediatric population. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 110: 760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Murch S, Jenkins H, Auth M, et al. (2013) Joint ESPGHAN and coeliac UK guidelines for the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease in children. Archives of Disease in Childhood 98: 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. (2020) European society paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 70: 141–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Leffler DA, Schuppan D. (2010) Update on serologic testing in celiac disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 105: 2520–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rahmati A, Shakeri R, Sohrabi M, et al. (2014) Correlation of tissue transglutaminase antibody with duodenal histologic marsh grading. Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases 6: 131–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Alessio MG, Tonutti E, Brusca I, et al. (2012) Correlation between IgA tissue transglutaminase antibody ratio and histological finding in celiac disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 55: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zanini B, Magni A, Caselani F, et al. (2012) High tissue-transglutaminase antibody level predicts small intestinal villous atrophy in adult patients at high risk of celiac disease. Digestive and Liver Disease 44: 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Tounian P, Sarrio F. (2017) Prise en charge diététique de certaines pathologies. In : Alimentation De L’enfant De 0 à 3 Ans, 3rd edn. Paris, France: Elsevier Masson, pp.97–116. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9782294748530/alimentation-de-lenfant-de-0-a-3-ans [Google Scholar]

- 98. Fayet L, Guex E, Bouteloup C. (2011) Gluten free diet: The practical points. Nutrition Clinique et Métabolisme 25: 196–198. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cegarra M. (2006) Gluten-free diet: A challenging follow-up. Archives de Pédiatrie 13: 576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Simpson S, Thompson T. (2012) Nutrition assessment in celiac disease. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 22: 797–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Schmitz J. (2013) Le régime sans gluten chez l’enfant. Pathologie Biologie 61: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Faure S, Pineau S, Amar É, et al. (2012) Pathologies et régimes alimentaires. Actualités Pharmaceutiques 51: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Battu C. (2017) L’accompagnement nutritionnel d’un patient souffrant d’une maladie cœliaque. Actualités Pharmaceutiques 56: 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Weber AL. (2012) La maladie cœliaque: physiopathologie et traitement. ”Guide” de conseils pour le pharmacien d’officine. Université de lorraine. Available at: https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-01733878 (accessed 14 March 2018). [Google Scholar]