Abstract

Drug abuse is a serious public health issue that may have irreversible consequences. Research has revealed that childhood psychological trauma can promote addictive behaviors in adulthood and that drugs are often used as a coping mechanism. Men are less likely to report trauma and seek help than women. The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the experience of men in Iceland who have abused drugs and experienced childhood psychological trauma, to increase knowledge and deepen the understanding of trauma and addiction. Participants were seven men who had both experienced childhood trauma and had a history of drug abuse. Two interviews were conducted with each participant. The main findings suggest that participants abused drugs as a coping mechanism due to the trauma experienced in childhood. For some participants, seeking companionship was a key component of their drug use. Participants were mostly dissatisfied with treatment resources in Iceland; waiting lists were long and too much focus was on religion. Five main themes were identified: emotional impact, self-medication for pain, gender expectations, impermanence of thoughts, and loss of a sense of wholeness. Increased societal and professional awareness of the linkage between trauma and drug abuse is needed, as are additional resources specific to men who have experienced childhood trauma and drug abuse. It is important to integrate trauma focused services into health-care settings to educate health-care professionals on trauma and the consequences thereof, in addition to utilizing screening tools such as the Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire for those seeking assistance.

Keywords: Drug abuse, childhood psychological trauma, coping mechanism, trauma focused service

Psychological Trauma in Childhood and Consequences

Drug abuse is a serious problem that adversely affects the health of consumers and can have irreversible consequences (Bryan, 2019; Fuchshuber et al., 2018). Abuse of alcohol and other drugs contributes to both morbidity and mortality. It is important to look at what drives people to abuse drugs and develop addiction. Previous research show that childhood trauma can lead to various problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Konkolÿ Thege et al., 2017) and drug abuse (Ai et al., 2016; Ertl et al., 2018).

Traumatic experiences are common among drug abusers, and studies have demonstrated up to 80%–90% prevalence (Barrett et al., 2015; Farley et al., 2004). Men’s trauma and drug abuse have been studied to some extent, although women seem to have gained much more attention from researchers (Gadie, 2017). While half of all children encounter violence in some form throughout their childhoods, only around half of the men who suffer from stress or other post-traumatic difficulties due to childhood trauma seek assistance upon reaching adulthood (Hillis et al., 2016; Sigurdardottir et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2005). Based on this information, men’s experience with trauma and drug abuse needs additional studying.

Effect on Mental Health Following Childhood Trauma and Gender Differences

Childhood trauma can cause physical, biological, and mental health problems (Afifi et al., 2016; Agorastos et al., 2014; Cowell et al., 2015). Long-term effects of childhood trauma are various, for example, suicide attempts, personality disorders, depression, PTSD, and poor quality of life. Under the influence of alcohol or other drugs, some individuals with drug addiction have reported improved mental health and subsequently felt as if they needed the substances to cope with everyday life (Ai et al., 2016; Choudhary et al., 2011; Ertl et al., 2016; Greger et al., 2015; Jansen et al., 2016; Tripodi & Pettus-Davis, 2013; Widom, 2014).

There appears to be a difference between genders when it comes to drug abuse as a result of trauma (Pace & Samet, 2016; Tolin & Foa, 2008). Although many encounter trauma throughout their lives, the type of trauma and resulting manifestations can vary between genders. Men are exposed to trauma as frequently as women, but their coping mechanisms are typically different than to those of women. Men are more likely than women to suppress their thoughts and feelings associated with traumatic experiences and to make attempts to ameliorate these manifestations, such as self-medicating with illicit drugs (Olff, 2017; Sigurdardottir et al., 2013). In addition, men seem to be less likely to report sexual trauma than women (Donne et al., 2018). It is important that health-care professionals understand the unique experiences and support needs of men and women (Cosden et al., 2015). Furthermore, it would be beneficial for providers of health-care services to adapt their programs so they are better suited to men, as it has been demonstrated that some processes are more likely to encourage them to seek help, such as structuring their content on positive male traits.

Trauma-Focused Service

Disclosure of psychological trauma is an important aspect in the process of healing, and it is important that people not suffer in silence with their experience (Furuta et al., 2018; Pfeiffer et al., 2018). Men are less likely than women to seek assistance for psychological trauma; they tend to rely more on themselves to deal with the trauma and are therefore often a hidden and vulnerable group (Masho & Alvanzo, 2010; Olff, 2017). Men are also more likely to exhibit self-harming behavior after trauma, such as participating in criminal activities or by abusing drugs (Schäfer et al., 2018).

Trauma-focused service is based on prevention, by screening for trauma and responding to the symptoms and consequences of those who have experienced trauma. It is important that the service is person centered and takes a holistic approach, looking into physical and mental factors as well as cultural and social aspects (Glennon et al., 2019; Rodríguez et al., 2019; Schäfer et al., 2018). When providing assistance to male clients, health-care professionals should evaluate their issues with regards to trauma. Failure to address traumatic experiences in the initial assessment can result in higher costs for the client and society as a whole (Greer et al., 2014).

Trauma screening is an important factor in trauma-focused care. It can provide the opportunity for disclosure, encouraging the individual to seek help and initiate their healing experience, and provide them with appropriate methods of treatment (Nillni et al., 2018; Sweeney et al., 2018). One method for trauma screening is the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) questionnaire, developed by Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda (Murphy et al., 2016). The list contains 10 Yes or No questions, with each Yes corresponding to one ACE score. People are asked about their experiences prior to the age of 18, including possible mental, physical, and sexual abuse, domestic violence, physical and emotional neglect, custody of a guardian, and parent’s mental health problems, addiction, time spent in prison, and divorce. It is estimated that approximately one in ten individuals has four or more ACEs. Six or more ACEs significantly increase the risk of suicide (Bellis et al., 2015; Felitti et al., 2004). Scores exceeding four points on the ACE suggest an increased likelihood of developing health issues in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998; Ho et al., 2019). Additionally, there appears to be a high correlation between ACE scores and substance dependence, in that the higher the ACE score, the more likely the individual relies on substances for the alleviation of trauma-related symptoms (Allem et al., 2015; Douglas, et al., 2010).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) based in the United Kingdom provides guidance on how to treat PTSD. Individual sessions of trauma-focused conversational therapy are recommended, either in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for 8–12 hr in total. Sessions are recommended to be at least once a week for 12 weeks, with the option of prolonging this time frame for clients in need of resolving multiple issues (NICE, 2005).

Table 1.

The 12 basic steps of the Vancouver School of Phenomenology.

| • Selecting dialogue partners (the sample). • First, there is silence (before entering a dialogue). • Participating in a dialogue (data collection). • Sharpened awareness of words (data analysis). • Beginning consideration of essences (coding). • Constructing the essential structure of the phenomenon for each case (individual case constructions). • Verifying the single case construction with the co-researcher. • Constructing the essential structure of the phenomenon from all the cases (metasynthesis of all the different case constructions). • Comparing the essential structure with the data. • Identifying the over-riding theme which describes the phenomenon (interpreting the meaning of the phenomenon). • Verifying the essential structure (the findings) with some research participants. • Writing up the findings. |

The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing post-traumatic symptoms has been demonstrated repeatedly. The principles of CBT appear to be most effective when applied during individual therapy, but can also have an impact when utilized in other trauma-focused therapy settings (Glennon et al., 2019; Sweeney et al., 2018).

Purpose of the Study and Research Question

The purpose of this study was to explore the experience of men in Iceland who have abused drugs and experienced childhood psychological trauma. The aim was to increase knowledge and deepen the understanding of the effects of traumatic childhood experiences on extensiveness of drug abuse in men. The research question was: What is the experience of men in Iceland who have abused drugs and experienced psychological trauma?

Method

Research Method

The Vancouver School of Phenomenology’s qualitative research method was considered most suited for the purposes of this study. The method is aimed at shaping the vision of each person according to the individual’s past experience (Halldorsdottir, 2000).

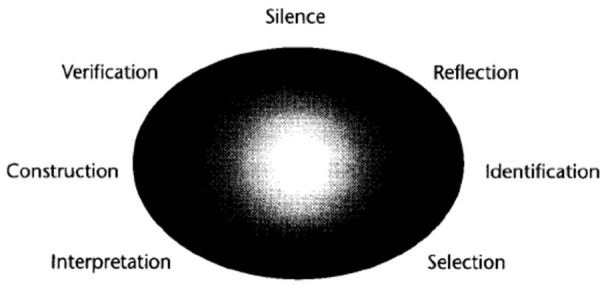

Data collection and analysis occurred during discussions between the participants and the researcher. The aim was to provide the researcher with a holistic view of the participants’ experience (Figure 1) (Halldorsdottir, 2000).

Figure 1.

The process of seven stages in the Vancouver School.

The research process involves seven stages that can be repeated when needed. The seven basic stages were silence, reflection, identification, selection, interpretation, construction, and verification. These stages are important in allowing the study to unfold as the research progresses (Halldorsdottir, 2000). The seven stages and 12 basic steps are mutually reinforcing and complementary aspects of the iterative research process.

The Research Process

The first step of the process involved the researchers selecting dialogue partners with personal experience in the subject matter. Their own experiences was the source of knowledge. In the second step, the researchers thoughtfully considered the phenomenon at hand. Utilizing silence from one of the seven stages, the researchers readied themselves for novel information and attempted to exclude any preconceived notions on what they might hear. The researchers also kept a journal throughout the entire research process to catalogue their thoughts while the study unfolded. The third step involved collecting data through dialogues. During this step, the researchers implemented in-depth interviews with the participants. The researchers had to be willing to listen to the experience of their dialogue partner and stay open to receiving new information.

According to the Vancouver School of Phenomenology, the dialogue should occur as in a normal conversation with a friend. The researchers must seek the truth and have the intention to understand the participant. In the fourth step, the dialogues that had been audiotaped during the third step were processed using Microsoft Word. The researchers then read through the transcripts multiple times to gain a sense of the experiences. The fifth step involved re-reading the transcripts and highlighting key statements or recurring themes. In the sixth step, the researchers grouped together the different themes portrayed in step five and constructed the phenomenon for each dialogue partner. During the seventh step, the researchers verified each case construction with each dialogue partner. The eighth step involved the search for common threads and differences throughout all cases collectively, as to locate the essential structure of the phenomenon. The researchers interpreted the words of the participants and attempted to convey what it was like to experience the phenomenon.

In the ninth step, the essential structure that had been identified was compared to the transcripts to confirm the findings. Dominant themes that best signified the phenomenon were identified during the tenth step; then, for the eleventh step, the analytic framework was presented to a selection of the participants to gauge whether the descriptions of their experiences were reflected accurately. For the twelfth and final step in the process, the findings were compiled, taking care to maintain the views of all participants and tell their stories using their own words (Halldorsdottir, 2000).

Participants and Recruitment

A purposive sample of seven Icelandic men participated in the study, all of which had a history of drug abuse and traumatic childhood experiences.

The criteria for participation were sobriety, that they were over the age of 18 years old, and male. There was no criteria for how long they had been sober. Participants were recruited through a Facebook advertisement placed on the January 31, 2019. Participants either responded directly to the researchers via email or were recommended by their acquaintances. No incentives or rewards were offered for participation. The average age of participants was 34 years.

Upon contacting the researchers, potential participants were questioned as to whether they fit the study’s criteria with regard to age, gender, and their history of childhood trauma and drug abuse. After being selected, participants decided on their preferred location for interview, where they were debriefed on the nature of the study, provided with contact information of a psychologist at their disposal, and a letter of consent. All participants were made aware of the fact that were no consequences should they wish to withdraw from the study at any point.

Ethics of the Study

All participants were given pseudonyms, and their identities kept from any of the data or reports related to the study. In addition, all personally identifiable data appearing in the interviews were withdrawn during transcription, and all recordings deleted immediately after being transcribed.

The permission of the Science Ethics Committee of Iceland was obtained, reference no: VSNb2018120002 / 03.01 with reference to the first paragraph, 12. gr. Act no. 44/2014 on scientific research in public health. In order to ensure none were forced into participation, participants were asked to contact the researcher voluntarily (Sigurdardottir et al., 2013). All participants were provided with information in the form of a leaflet prior to the interview and gave their signed consent prior to the interviews. Optional psychological assistance was made available to them following the interviews.

Validity and Reliability

Credibility was used to enhance fairness and reliability. Participants had no time limits to their interviews as to offer them unrestricted expression of their experiences. Data were reviewed thoroughly, and the accuracy of the data confirmed by participants. Data were also presented to students and supervisors both at the research stage and upon completion of the study (Sigurdardottir et al., 2013).

Results

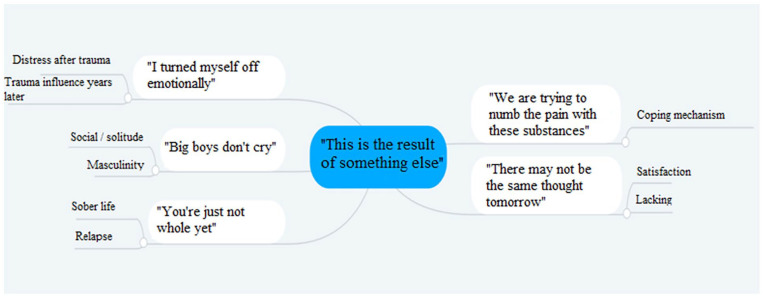

This study examined the experience of men who had abused drugs and experienced trauma. Data collection and analysis were conducted according the twelve steps as previously mentioned. Five main themes were identified and presented in an analysis model (Figure 2) with one to two subthemes. The main findings of the study indicate that the participants’ drug abuse was often the direct or indirect result of some other factor, or a coping mechanism, especially with regard to traumatic experiences. Findings also indicate a perceived lack of understanding within the health-care system and among the general public that trauma may be the underlying cause of drug abuse, and is thus often overlooked.

Figure 2.

Analysis model of identified main and subthemes.

“I Turned Myself Off Emotionally”

The first main theme refers to how the participants dealt with the trauma they experienced. This theme includes the following subthemes: distress after trauma, and trauma influence years later. All participants experienced mental health issues following the traumas they had experienced. The traumatic experiencing significantly impacted their daily lives, and the participants revealed they were still dealing with the consequences of the trauma to some extent at the time of the interviews.

Distress After Trauma

Immense distress was associated with the traumas. Steven spoke of his parents’ divorce having had a profound effect on him. He found it hard to trust people and shut himself out. After the violence that Oliver experienced in his youth, he said he distrusted everyone. He grew up in a home where he was subjected to mental, physical, and sexual abuse, which caused him tremendous anxiety. He said: “I did not sleep for weeks, except for a few minutes at a time, I was always on edge, I hardly slept.” Jack talked about the depression he experienced after growing up enduring violence from his parents. He had also experienced intense anxiety along with compulsion and obsession, and said:

. . . and instead of being comforted or asked if something was wrong, they just came into my room and screamed at me . . . with clenched teeth it was disgusting . . . it was naturally just worse, then I just cried more. . . but then I remember there was a term I heard often when I was a kid, it was . . . *father’s name* beat that boy.

After Peter’s traumatic experiences, he experienced suicidal thoughts. They were extreme and long lasting; he described it: “The will of life disappeared and really just ceased.” Suicidal thoughts following Gavin’s traumas were so bad that after a while he decided he wanted to end his life: “I had decided to just throw myself off the eighth floor.”

Traumas Still Have Effects Years Later

All participants mentioned that the effects of their traumatic experiences still followed them to some extent. John said: “I feel like I have been held back in life because of my upbringing, I have never been able to save money because I wanted to get out of the situation as soon as possible, the traumas I experienced shaped my life.”

Peter is still struggling with a great deal of mental difficulties, which he considered to be a direct consequence of his traumatic experiences. He said: “It takes a lot of time to process such trauma and it does not work to just be treated for addiction and get out of rehab cured. There is so much that needs to be worked on too, if you do not work on it, then it doesn’t go away.”

The traumatic experiences and their effects will, according to Oliver, follow him for the rest of his life. He revealed that men of a certain age were considered a threat to him. These men were of similar age to his foster father. Oliver was quick-tempered, and for many years following the early traumatic experiences, he exhibited violent behavior.

Henry stated that his thought processes had changed after experiencing trauma. He said: “Each individual’s story didn’t matter; everyone could die at any time. The biggest lesson I learned had been to just do what I liked and enjoyed.”

The traumatic experiences of Jack’s childhood were still affecting him, and he said he was afraid of any conflict. Violence used to be a regular thing for him, and if anyone made fun of him, he did not hesitate to beat them up:

I remember my mom was going to be violent with me and I just beat her to a pulp with a belt. Then all of a sudden I was the idiot . . . I remember . . . then they were going to put me in a psych ward because I was being violent . . . you know this made no sense to me, why can they beat me but when I hit them back I am an idiot, you know?

“You’re Just Not Whole Yet”

The second main theme of the findings involves sobriety and relapse, with the subthemes: sober life, and relapse and its causes.

Sober Life

All participants mentioned feeling better at the time of the interviews and that sobriety often accompanied an improvement in their mental well-being. They were all sober when the interviews took place. Henry said: “Each day is different, and today I feel good but differently tomorrow. I must stay busy to keep from feeling bad and relapsing.” In sobriety, Oliver said that he felt great and that he enjoyed having a lot to do. He had learned positive thinking, which he was introduced to him in CBT. Peter talked about everything going in the right direction; he had worked a lot on his mental difficulties in recent years. Jack spoke of feeling fine sober and that he did not experience bad feelings about not using drugs. However, the feeling varied from day to day.

Each day was different according to Steven, and he has his good days and bad days. However, he said: “I feel incredibly well after I started living without substances and over time it has become easier to stay away from drugs.” John described that how he felt wonderful sober and far better than he felt while using drugs. Gavin said:

I am feeling much better than I used to. The days don’t constantly revolve around looking at the clock, worrying about not reaching the liquor store before closure, or constantly trying to find a dealer, and that is something I am glad to be free of.

Relapse and Its Causes

Some of the participants talked about relapsing and the reasons for doing so. Neither John nor Oliver considered it a relapse if they used drugs occasionally; they said they had it under control. Other participants needed to completely stay away from drugs to avoid relapsing. Peter said: “I relapsed at one point, and it was followed by a great deal of depression and anxiety, first and foremost because you just have not recovered yet.” Steven said he had never relapsed after he completed his treatment for substance abuse. He said people tend to go back to the same group of friends after treatment, and that could be the main reason for the majority of relapses. Gavin had previously relapsed after being sober for some time, and he said that this had been accompanied by great distress. He considered it important to treat himself on his own terms because of his previous experiences:

. . . grabbed me and said you’re going to treatment my friend. That treatment I was really all in but . . .because it was not on my terms I think, I almost just relapsed right away . . . just two, three months after I got home.

Henry said that when he had relapsed before, he had experienced a great deal of misery and he said the thought of relapsing was very distressing. When he had relapsed, he felt like he had failed everyone and tried to isolate so that people wouldn’t notice it.

“We Are Trying to Numb the Pain With These Substances”

The third main theme refers to how the participants used the drugs as a coping mechanism as a result of the bad feelings they were experiencing after the trauma. The theme includes the coping mechanism subtheme.

Coping Mechanism

In his own words, Peter felt there was a direct connection between his mental distress and the initiation of his substance abuse, which continued for a prolonged period of time. He claimed his distress was the result of the traumatic experiences he had suffered. When he felt bad, the drugs brought him the relaxation he sought:

The reason is simply that . . . I . . . I used the drugs just to feel good. The reason is simply that I knew no other way. And just inadvertently found this way. Just basic just knew nothing else . . . didn’t know where to look, tried to look for something else, found nothing . . . but found this way . . . this was just clearly a way to get away from bad feelings. You felt good that evening or whatever you call it. It worked well for a few years. It just . . . just to turn off your head and relax and feel good. So yeah, direct connection between just bad feelings and naturally you know the discomfort comes naturally straight from . . . from these traumas.

Steven said it was often a matter of fighting oneself when one felt entitled to a reward for staying sober so long. He said it was astounding the lengths people would go to justify their own use: “Hey I’ve been sober for so long, I can totally have some now.”

“Big Boys Don’t Cry”

The fourth theme refers to how society and environment can influence the drug abuse in certain cases. This theme includes the following subthemes: social group/solitude, and masculinity. The participants all had some experience with environmental factors affecting their mental health and drug use, particularly with regard to societal influences and views on masculinity.

Social Group/Solitude

In Steven’s opinion, the social group he was a part of, contributed to his drug abuse: “I both gained more confidence around people when I was using drugs and it was difficult to say no to my friends when they offered.” John also spoke of his social group affecting his drug abuse; his friends smoked and the get-togethers proceeded to revolve around the drugs. Henry’s social group played a part in how he started using drugs. He said: “It was fun at first, but later it led to the use of stronger drugs, then it stopped being fun.” Jack avoided being at home with his family and tried to spend as much time as he could with his friends. Isolation from family and a normal social life led him into seeking out this social group, which in the end seemed to only revolve around the drugs.

Unlike the others, social groups did not play a role in Gavin’s or Peter’s misuse of drugs. Gavin mostly used drugs at home by himself. Peter said he hadn’t had any friends who used drugs and that he only used the drugs when he was alone at home: “My drug abuse only occurred in my home with me and my PlayStation computer.”

Masculinity

Society’s view of men had a huge impact on Peter when searching for alternatives to societal norms of masculinity: “The image of masculinity in society is too much about being a tough guy and not being able to talk about emotional issues.” In Jack’s opinion, this view of masculinity was worse a few years ago but seems to be advancing in a more positive direction nowadays.

Henry explained that he did not feel like society deterred men from discussing their mental well-being but rather believed that it had become ingrained in society for men to expect an adverse reaction when they did open up about such issues:

A lot of people say they just have to toughen up and . . . get through it and so . . . what happens? They hide the feelings inside . . . they develop depression, anxiety, you know and yes . . . more mental issues . . .

Oliver agreed there certainly was a group that thinks like this, but it does not come from other men or male groups of friends. This would be a certain group of women who criticize men if they try to express themselves. Steven said he was slightly affected by this social pressure, but he believed men were their own worst enemies. John said: “There was societal pressure on men not to talk about mental distress and bad feelings a few years ago, now there is much more discussion about this issue.” Gavin explained that he did not feel encouragement from others to confide on these matters.

“There May Not Be the Same Thought Tomorrow”

The fifth and final main theme refers to addiction treatment, and the opportunities and obstacles men face when encountering treatment options in Iceland. This theme includes the following subthemes: satisfaction with treatment options, and lack of treatment resources.

Satisfaction With Treatment Options

Steven’s experience with treatment for his drug addiction was reportedly good to some extent. In his opinion, the staff had been nice; everyone had been helpful, and the leisure time enjoyable. Jack learned several things during his stay in treatment, including skills that he incorporated into everyday life. Henry also learned a great deal from his treatment, and felt he had benefited from it. The time Gavin spent in treatment had been fine in his opinion: “Time seemed to slow down the first few days but then it went by very fast.” Peter claimed his treatment had been good and very informative. He had also taken advantage of the CBT made available to him.

Two of the participants had not gone to treatment. John realized that he either had to go to treatment or quit using himself: “It was either treatment or I would do something about it myself and I first decided to do something about it myself; today I am in control of my addiction and I am aware of it if I start to lose control.” Oliver explained that he had been able to stop using drugs on his own and had not felt the need for treatment. He had discovered the reasons for his drug misuse and that knowledge had helped him to give it up.

Lack of Treatment Resources

The participants mentioned that they found a few things lacking during their treatments. Jack had found a lack of staff with relevant qualifications in drug addiction and recovery. In addition, he felt there had been too much focus applied to religious work, which he had disliked.

According to Steven: “There was a lack of individualized treatment, I was placed in the same group as addicts who had been abusing drugs for much longer and I did not feel like part of that group.” He felt the worst part of his treatment had been the mandatory Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings, during which faith had been a frequent topic, but he was not a religious man.:

It is very difficult for . . . for individuals like me in this case who have never you know . . . never become homeless and been at the rock bottom that is sometimes talked about . . . that it is incredibly difficult to be . . . to have not experienced this and to be next to someone that has gone lower than the bottom and managed to climb up and just yeah I have it pretty good. . .

Henry believed he had little in common with other members in his group. He had not felt like he belonged in Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings, where he encountered a considerable amount of stigma and propaganda. He also believed the waiting lists for treatment were far too long which could sometimes make matters worse. Gavin said:

I wanted more psychologists in the treatment resources I sought, and it would be good to have more varied activities, there is a need for greater emphasis on mental well-being when it comes to drug treatment: “. . . because the root is often much, much, much deeper.”

Peter felt the most pressing concern had been the lack of information on how to maintain his sobriety post-treatment. He had not received any information on how to proceed in his recovery upon completion of his treatment. Too much focus had been on the addiction itself and not on finding the reasons or possible causes for the addiction; it was imperative to acknowledge that other factors could be at play. John did not go to treatment, explaining: “If I went to treatment, I would probably need a different way of thinking since faith-related treatment does not apply to me.” Oliver did not believe in some of the teachings imparted in his therapy, referring to AA and the accompanying religious work, of which treatment is often comprised.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore the experience of men in Iceland who have abused drugs and experienced childhood psychological trauma. The findings of the study revealed five main themes: emotional impact, self-medication for pain, gender expectations, impermanence of thoughts, and loss of wholeness. These findings are of importance as they expand on previous research and convey a deeper understanding of the effects of experiencing childhood trauma on subsequent drug abuse in men.

The high rate of occurrence of traumatic childhood experiences amongst all participants had not been anticipated. It was evident from the findings the importance for men to receive adequate psychological help for their traumatic experiences during their time in treatment. The participants had not found the available assistance to be sufficient in considering these factors, where addiction had been perceived to be the primary focus in treatment and no thought given to underlying causes such as traumatic experiences.

All participants reported feeling fine in general without the influence of drugs at the time of the interviews. Some had experienced relapses and believed them to have occurred due to their poor mental health. Individuals with a history of childhood trauma and subsequent drug abuse are predisposed to relapsing after a period of sobriety, when facing difficult and distressing situations. Previous research has repeatedly revealed the incentive for relapsing to be the desensitization of feelings when individuals have been subjected to a great deal of distress (Garami et al., 2018; Heffner et al., 2011; Wadsworth et al., 1995).

According to the participants, there seemed to be a certain level of silencing in the community regarding drug abuse as a result of trauma. Increased attention needed to be extended toward this issue in treatment options in Iceland, by seeking out the root causes of the problem and not only focusing on the addiction itself. All participants were alike in having used drugs as a coping mechanism for the distress originating from the trauma they had suffered in childhood.

Impact on Mental Health

The long-term effects of traumatic childhood experiences on the participants’ mental health were evident, as illustrated by their symptoms of depression, PTSD, and addiction. These findings are in line with previous research demonstrating an increased likelihood of experiencing poor mental health when individuals are violated or otherwise abused during childhood (Ai et al., 2016; Ertl et al., 2018).

Psychological traumas during childhood can exacerbate a variety of disorders later in life, such as addictive behavior (Ertl et al., 2018). This corresponds to the current study’s findings, where the traumatic experiences continue to have an effect on the participant’s lives many years later.

When the participants spoke of the causes for relapsing, it became apparent that their mental distress was associated with their relapses. They explained that relapses had been accompanied by a great deal of negative emotions, and it was evident that some of the participants felt they had failed their relatives and themselves, which is in accordance with findings from previous studies (Chauhan et al., 2018).

Drugs as a Coping Mechanism

According to studies by Ai et al. (2016) and Sanders et al. (2018), it is common for individuals who have experienced childhood traumas to use drugs as a form of coping mechanism. These findings are consistent with the results from the current study, where participants explained they had used drugs to calm their minds and experience relaxation without having to ruminate on distressing thoughts.

Using drugs as a remedy for distress can develop into a habit, and after a certain period of time, the individual begins to feel as though they need the substances in order to cope with everyday life (Ertl et al., 2018). The participants spoke of getting rid of the distress, escaping reality, and that while they were high, life revolved around easier things, which is also consistent with previous findings (Ertl et al., 2018).

Environmental Impact

Some of the participants revealed that their social groups were one of the reasons for their initial drug use; some had continued to use around their friends, while others had continued their use by themselves. Participants were however all in agreement that their continued use had been as a result of their mental distress. Previous research has reported on the influence of acquaintances with regard to drug use, but often the group’s attributes become the personality traits of the individual, who assumes the characteristics of the group (Dingle et al., 2015).

As was made evident in the current study, it appears to be a common occurrence for individuals to abuse drugs in solitude, increasing the likelihood of developing a daily habit that may also deter them from seeking assistance (Tam et al., 2018). The study revealed that the social male norms of the community may have contributed to the distress of some of the participants (Tryggvadottir et al., 2019). However, the majority agreed that views on the subject had advanced and restrictive gender norms had been more of a problem several years ago. This could be a sign of progress, as previous studies have reported a negative association between perceived male gender norms, mental health, and social functioning in men (Wang & Miller, 2017).

Opinion on Treatment and Trauma-Focused Service

The participants were dissatisfied with the religious aspect in treatment, with one participant explaining that he would have had to completely alter his mindset for it to apply to him, in accordance with the study by Tonigan et al. (2002). Religion in treatment facilities is a debatable course of action as some might consider it insensitive and problematic with regard to cultural differences (Matamonasa-Bennet, 2015). Waiting lists were also mentioned as an obstacle, and there was a lack of information on resources after treatment. Individuals who perceive treatment options as unavailable to them tend to be left with inadequate treatment options, or as this study shows, no treatment at all (Valdez et al., 2018). Post-treatment care should encourage ongoing recovery and individuals often find it helpful to meet other people in similar post-treatment situations (Pulford et al., 2010).

Detoxification is the most common method used in treatment resources in Iceland and in many other countries (Luty, 2003). Luty (2003) revealed that this method of sudden withdrawal is ineffective and that other methods would achieve more success in helping people to attain sobriety, such as motivational interviewing.

Trauma-focused services should be considered when health-care professionals are providing assistance to those with health problems and a history of substance abuse, by screening for possible traumatic experiences and providing those who have experienced trauma with the help they need. As previously mentioned, trauma-focused services are based on prevention, providing an ideal method on how to respond to the symptoms of those who have experienced trauma, in addition to potentially reducing the likelihood of these individuals turning to substance abuse as a coping mechanism (Glennon et al., 2019; Greer et al., 2014); Rodríguez et al., 2019; Schäfer et al., 2018).

Limitations and Future Research

Due to the small number of participants, the results of this study are not suited to reflecting the general public. Furthermore, full comprehension and immersion of the participant’s experiences may not have been achieved, as only two interviews were concluded with each participant.

Exploring this issue with a higher number of participants would provide a deeper and greater understanding on the subject of traumatic childhood experiences and drug abuse. A quantitative study in Iceland could better illuminate the link between childhood trauma and drug abuse. Further research on treatment center waiting lists and their influence on sobriety would be informative, as would evaluating the association between length of time spent waiting for treatment and substance abuse.

Five out of the seven men in the study had managed to abstain from using drugs at the time of the interviews post-treatment, and the remaining two had taken control of their drug use without the need for treatment. The length of time post-treatment and whether it influences improvements in mental health, in addition to considering the reasons why some people manage to completely abstain from relapsing while others relapse repeatedly, are all interesting matters warranting further investigation. The participants of this study all spoke of daily nuances to their recovery, with the challenges they faced varying on a daily basis.

Conclusions

From these findings, it can be concluded that there is a perceived lack of understanding amongst professionals and throughout the community of the underlying causes for men’s drug abuse. The results suggest that those who abuse drugs are not necessarily doing it only based on the desire for the substance itself, but rather in hopes of the substance providing them with a sense of relief from memories, thoughts, and feelings they find difficult to process. Based on the results from this study, it is imperative that individuals who have encountered traumatic experiences be provided with individualized trauma-focused care.

It is not uncommon to hear of individuals or relatives who have lost their lives due to excessive drug abuse. Unfortunately, these tragedies occur as frequently in Iceland as elsewhere. Individuals resorting to substance abuse in order to improve their mental well-being is a sad realization, but it is imperative that steps be taken to better understand and assist those who see no alternative options. When substance abuse has developed into a desperate attempt at escaping distress, it appears obvious that the drugs have stopped being the main incentive for use. No one should be in a situation where they consider their only choices to be either numbing themselves into oblivion or taking their own lives.

Utilization of Research Findings

Innovations: The research findings expand on previous knowledge and deepen the understanding of the consequences of childhood trauma. Important information regarding the possible underlying causes of drug abuse emerged from the study which should be considered in future research.

Utilization: As traumatic experiences are often a reason for subsequent drug abuse, it is imperative that trauma-focused services be included in treatments for drug addiction.

Knowledge: The results of the study can serve as a basis for conversations with those who have experienced trauma and those in treatment for drug addiction.

Impact on Health-Care Professionals: Health-care workers should provide appropriate treatment for individuals seeking assistance, and provide them with information on available treatments. Contributing to the awareness of health-care professionals on the effects of childhood trauma is critical, along with the consideration of trauma-focused approaches when assisting those with a history of substance abuse.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Margret Torshamar Georgsdottir  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9394-5991

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9394-5991

Sigrun Sigurdardottir  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2898-3240

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2898-3240

References

- Afifi T. O., MacMillan H. L., Boyle M., Cheung K., Taillieu T., Turner S., Sareen J. (2016). Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Reports, 27(3), 10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agorastos A., Pittman J. O. E., Angkaw A. C., Nievergelt C. M., Hansen C. J., Aversa L. H., Parisi S. A., Barkauskas D. A., Marine Resiliency Study Team, & Baker D. G. (2014). The cumulative effect of different childhood trauma types on self-reported symptoms of adult male depression and PTSD, substance abuse and health-related quality of life in a large active-duty military cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 58, 46–54. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ai A., Lee J., Solis A., Yap C. (2016). Childhood abuse, religious involvement, and substance abuse among Latino-American men in the united states. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(6), 764–775. 10.1007/s12529-016-9561-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem J., Soto D. W., Baezconde-Garbanati L., Unger J. B. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and substance use among Hispanic emerging adults in Southern California. Addictive behaviors, 50, 199–204. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. L., Teesson M., Chapman C., Slade T., Carragher N., Mills K. (2015). Substance use and mental health consequences of childhood trauma: An epidemiological investigation. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 146, e217–e218. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.059 [DOI]

- Bellis M. A., Hughes K., Leckenby N., Hardcastle K. A., Perkins C., Lowey H. (2015). Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: A national survey. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 37(3), 445–454. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan R. H. (2019). Getting to why: Adverse childhood experiences’ impact on adult health. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(2), 157. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.09.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan V. S., Nautiyal S., Garg R., Chauhan K. S. (2018). To identify predictors of relapse in cases of alcohol dependence syndrome in relation to life events. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 27(1), 73–79. 10.4103/ipj.ipj_27_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary E., Smith M., Bossarte R. M. (2011). Depression, anxiety, and symptom profiles among female and male victims of sexual violence. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(1), 28–36. 10.1177/1557988311414045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosden M., Larsen J. L., Donahue M. T., Nylund-Gibson K. (2015). Trauma symptoms for men and women in substance abuse treatment: A latent transition analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 50, 18–25. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell R. A., Cicchetti D., Rogosch F. A., Toth S. L. (2015). Childhood maltreatment and its effect on neurocognitive functioning: Timing and chronicity matter. Development and Psychopathology, 27(2), 521. 10.1017/S0954579415000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle G. A., Stark C., Cruwys T., Best D. (2015). Breaking good: Breaking ties with social groups may be good for recovery from substance misuse. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(2), 236–254. 10.1111/bjso.12081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donne M. D., DeLuca J., Pleskach P., Bromson C., Mosley M. P., Perez E. T., Mathews S. G., Stephenson R., Frye V. (2018). Barriers to and facilitators of help-seeking behavior among men who experience sexual violence. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(2), 189–201. 10.1177/1557988317740665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K. R., Chan G., Gelernter J., Arias A. J., Anton R. F., Weiss R. D., Brady K., Poling J., Farrer L., Kranzler H. R. (2010). Adverse childhood events as risk factors for substance dependence: Partial mediation by mood and anxiety disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 35(1), 7–13. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl V., Preusse M., Neuner F. (2018). Are drinking motives universal? Characteristics of motive types in alcohol-dependent men from two diverse populations. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 38. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley M., Golding J. M., Young G., Mulligan M., Minkoff J. R. (2004). Trauma history and relapse probability among patients seeking substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(2), 161–167. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J., Anda R. F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D. F., Spitz A. M., Edwards V., Koss M. P., Marks J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J., Dube S. R., Williamson D. F., Thompson T. J., Loo C. M., Giles W. H. (2004). The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 771–784. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchshuber J., Hiebler-Ragger M., Kresse A., Kapfhammer H., Unterrainer H. F. (2018). Depressive symptoms and addictive behaviors in young adults after childhood trauma: The mediating role of personality organization and despair. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 318. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M., Horsch A., Ng E. S. W., Bick D., Spain D., Sin J. (2018). Effectiveness of trauma-focused psychological therapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women following childbirth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadie R. (2017). A call to action for health disparities in boys and men: Innovative research on addiction, trauma and related comobidities. Journal of Arts Writing by Students, 3(1), 3–4. 10.1386/jaws.3.1-2.3_2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami J., Valikhani A., Parkes D., Haber P., Mahlberg J., Misiak B., Frydecka D., Moustafa A. (2018). Examining perceived stress, childhood trauma and interpersonal trauma in individuals with drug addiction. Psychological Reports, 122, 433–450. 10.1177/0033294118764918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon A., Pruitt D. K., Polmanteer R. S. R. (2019). Integrating self-care into clinical practice with trauma clients. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(1), 48–56. 10.1080/10911359.2018.1473189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer D., Grasso D. J., Cohen A., Webb C. (2014). Trauma-focused treatment in a state system of care: Is it worth the cost? Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41(3), 317–323. 10.1007/s10488-013-0468-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger H., Myhre A., Lydersen S., Jozefiak T. (2015). Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 122–134. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldorsdottir S. (2000). The Vancouver School of doing Phenomenology. In Fridlund og B., Hildingh C. (Eds.), Qualitative methods in the service of health (bls. 47–81). Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner J. L., Blom T. J., Anthenelli R. M. (2011). Gender differences in trauma history and symptoms as predictors of relapse to alcohol and drug use. American Journal on Addictions, 20(4), 307–311. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S., Mercy J., Amobi A., Kress H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079. 10.1542/peds.2015-4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho G. W. K., Chan A. C. Y., Chien W., Bressington D. T., Karatzias T. (2019). Examining patterns of adversity in chinese young adults using the Adverse Childhood Experiences—International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 179–188. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen K., Cardoso T. A., Fries G. R., Branco J. C., Silva R. A., Kauer-Sant’Anna M., Kapczinski F., Magalhaes P. V. S. (2016). Childhood trauma, family history, and their association with mood disorders in early adulthood. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134, 281–286. 10.1111/acps.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkolÿ Thege B., Horwood L., Slater L., Tan M. C., Hodgins D. C., Wild T. C. (2017). Relationship between interpersonal trauma exposure and addictive behaviors: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 164. 10.1186/s12888-017-1323-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luty J. (2003). What works in drug addiction? BJPsych Advances, 9(4), 280–287. 10.1192/apt.9.4.280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masho S. W., Alvanzo A. (2010). Help-seeking behaviors of men sexual assault survivors. American Journal of Men’s Health, 4(3), 237–242. 10.1177/1557988309336365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamonasa-Bennet A. (2015). “The poison that ruined the nation”: Native American men-alcohol, identity, and traditional healing. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 1142–1154. 10.1177/1557988315576937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A., Steele H., Steele M., Allman B., Kastner T., Dube S. R. (2016). The clinical adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaire: Implications for trauma-informed behavioral healthcare. Integrated Early Childhood Behavioral Health in Primary Care, 7–16. 10.1007/978-3-319-31815-8_2 [DOI]

- NICE. (2005). Post-traumatic stress disorder: Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg26/chapter/1-Guidance#the-treatment-of-ptsd

- Nillni Y. I., Mehralizade A., Mayer L., Milanovic S. (2018). Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 136–148. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: An update. European Journal of Psychotraumatologhy, 8(4). 10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C. A., Samet J. H. (2016). Substance use disorders. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(7), ITC49. 10.7326/AITC201604050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E., Sachser C., Rohlmann F., Goldbeck L. (2018). Effectiveness of a trauma-focused group intervention for young refugees: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(11), 1171–1179. 10.1111/jcpp.12908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulford J., Black S., Wheeler A., Sheridan J., Adams P. (2010). Providing post-treatment support in an outpatient alcohol and other drug treatment context: A qualitative study of staff opinion. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(3), 471–481. 10.1007/s11469-009-9218-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez R. R, Palacios A., Alonso T. J., Pérez P., Álvarez E., Coca A., Mencía S., Marcos A., Mayordomo-Colunga J., Fernández F., LIorente A. (2019). Burnout and posttraumatic stress in paediatric critical care personnel: Prediction from resilience and coping styles. Australian Critical Care, 32(1), 46–53. 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J., Hershberger A. R., Kolp H. M., Um M., Aalsma M., Cyders M. A. (2018). PTSD symptoms mediate the relationship between sexual abuse and substance use risk in juvenile justice–involved youth. Child Maltreatment, 23(3), 226–233. 10.1177/1077559517745154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer I., Hopchet M., Vandamme N., Ajdukovic D., El-Hage W., Egreteau L., Javakhishvili J. D., Makhashvili N., Lampe A., Ardino V., Kazlauskas E., Mouthaan J., Sijbrandij M., Dragan M., Lis-Turlejska M., Figueiredo-Braga M., Sales L., Arnberg F., Nazarenko T., . . .Murphy D. (2018). Trauma and trauma care in europe. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1). 10.1080/20008198.2018.1556553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir S., Halldorsdottir H., Bender S. S. (2013). Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: Gender similarities and differences. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42(3), 278–286. 10.1177/1403494813514645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney A., Filson B., Kennedy A., Collinson L., Gillard S. (2018). A paradigm shift: Relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Advances, 24(5), 319–333. 10.1192/bja.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam C. H., Kwok S. I., Lo T. W., Lam S. H., Lee G. K. (2018). Hidden drug abuse in hong kong: From social acquaintance to social isolation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 457. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D. F., Foa E. B. (2008). Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, S(1), 37–85. 10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan J. S., Miller W. R., Schermer C. (2002). Atheists, agnostics and alcoholics anonymous. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 534–541. 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi S. J., Pettus-Davis C. (2013). Histories of childhood victimization and subsequent mental health problems, substance use, and sexual victimization for a sample of incarcerated women in the US. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36(1), 30–40. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryggvadottir E. D., Sigurdardottir S., Halldorsdottir S. (2019). ‘The self-distruction force is so strong’: Male survivors’ experience of suicidal thoughts following sexual violence. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 33(4), 995–1005. https://doi.org/10.1111.scs.12698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez L. A., Garcia D. O., Ruiz J., Oren E., Carvajal S. (2018). Exploring structural, sociocultural, and individual barriers to alcohol abuse treatment among Hispanic men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1948–1957. https://doi.org/1177/1557988318790882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth R., Spampneto A. M., Halbrook B. M. (1995). The role of sexual trauma in the treatment of chemically dependent women: Addressing the relapse issue. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(4), 401–406. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01772.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. S., Lane M., Olfson M., Pincus H. A., Wells K. B., Kessler R. C. (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 629–640. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Miller K. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 80–93. 10.1037/cou0000176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom C. S. (2014). The 2013 Sutherland address: Varieties of violent behavior. Criminology, 52(3), 313–344. 10.1111/1745-9125.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]