Introduction

H syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that occurs because of mutations in the SLC29A3 gene, encoding the human equilibrative nucleoside transporter, which is a protein located in endosomes, lysosomes, and mitochondria.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 It was first named by Molho-Pessach et al in 2008.1 To date, fewer than 120 cases of this rare disease have been reported worldwide.5 It is characterized by the presence of hyperpigmented indurated patches with overlying hypertrichosis symmetrically involving the inner aspects of the thighs, which may extend to the posterior aspects of the lower limbs, abdomen, and back, while sparing the knees and buttocks. Other important features of H syndrome include sensorineural hearing loss, hyperglycemia/insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, heart anomalies, hypogonadism, low height (short stature), and hepatosplenomegaly.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Currently, many investigators consider H syndrome as a novel form of histiocytosis.4,7

In this case series, 3 cases are reported with findings consistent with H syndrome, in addition to new findings that have not been reported in the literature. All 3 of our patients have low bone mineral density associated with musculoskeletal pain, they also have hypovitaminosis D with secondary hyperparathyroidism, and they responded well to vitamin D supplements.

Case series

Patient 1

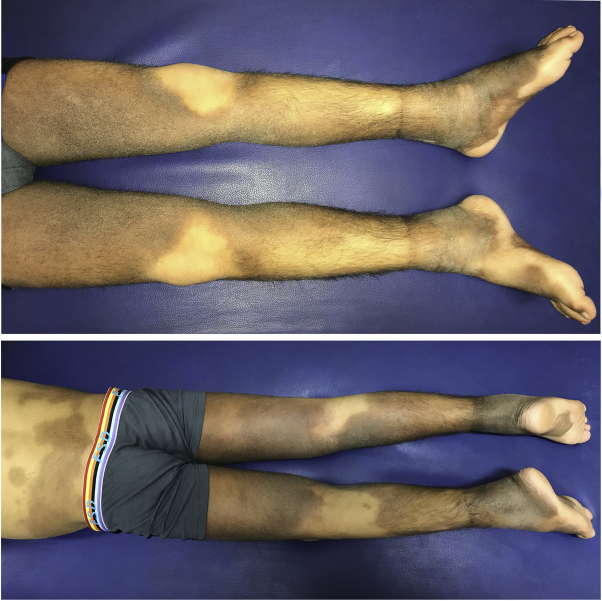

A 21-year-old Iraqi man, born of first-cousin healthy parents, was referred to our outpatient clinic at Al-Sadr Teaching Hospital for hyperpigmented indurated patches that were symmetrically distributed over the lower limbs, especially the inner aspects of the thighs. These patches were overlying with hypertrichosis (Fig 1). At the age of 16, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was diagnosed, and, according to the patient, skin lesions started to appear 1 year later on the calves, which spread within a span of 2 years to involve the inner aspects of the thighs, the ankles, and lower abdomen. The lesions were tender by palpation. The patient also had bilateral ankle joint swelling and pain, bilateral hallux valgus deformities, bone pain, and muscle pain. The family history showed that the patient has 2 brothers with the same complaints, the older of whom died at the age of 20 of renal failure; the other is patient 2 in this current case series. Palpation of the groin found tender lymphadenopathy. The patient has no hearing loss or cardiac problems. A dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan found low bone mineral density (BMD) (Z-score, −2.4). For summary of the clinical findings and laboratory test results, see Tables I and II.

Fig 1.

Hyperpigmented hypertrichotic patches symmetrically involving the inner aspects of the thighs, calves, and feet of patient 1.

Table I.

Summary of the clinical findings in all 3 patients

| Findings | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the patient at the time of evaluation, (y) | 21 | 17 | 17 |

| Weight (kg) | 48 | 27 | 49.2 |

| Weight for age (SD) | −2.49 | −4.35 | −1.64 |

| Height (cm) | 165 | 127 | 162 |

| Height for age (SD) | −1.61 | −6.32 | −1.58 |

| Hyperpigmented patches and hypertrichosis | + | + | + |

| Hallux valgus deformities/flexion contractures of fingers and toes | + | + | + |

| Ankle swelling and tenderness | + | + | + |

| Low BMD | + | + | + |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy | + | + | + |

| Hearing loss and speaking problems | − | + | + |

| Short stature | + | + | + |

| Hypogonadism and gynecomastia | − | + | + |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus | + | + | − |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | − | + | + |

| Exophthalmos and corneal arcus | − | + | + |

| Scrotal masses with a swollen and retracted penis | − | + | − |

| Abnormal ear shape | − | − | + |

SD, Standard deviation.

Table II.

Summary of the laboratory findings in all 3 patients

| Laboratory tests | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ESR (mm/h) (normal range, 0-15 mm/h) |

↑49 | ↑110 | ↑93 |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) (normal range, 11.5-16.5 g/dL) |

12.8 | ↓10.2 | ↓11.1 |

|

Vitamin D (ng/mL) (normal range, 30-100 ng/mL) |

↓16.2 | ↓8.2 | ↓17.3 |

|

Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) (normal range, 10-55 pg/mL) |

↑234 | ↑212 | ↑327 |

|

Phosphorus (mg/dL) (normal range, 2.3-4.7 mg/dL) |

4.67 | 4.62 | 4.2 |

|

Calcium (mg/dL) (normal range, 8.5-10.5 mg/dL) |

10.4 | 9.3 | 9.2 |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) collected in the morning (normal range at morning, 171-536 nmol/L) | ↑636.1 | 339.5 | ↑1030 |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) collected in the morning (normal range, 2.8-8 ng/mL) | 4.26 | ↓0.025 | ↓2.63 |

|

LH (mIU/mL) (normal range, 0.95-11.95 mIU/mL) |

7.08 | ↓0.09 | 5.6 |

|

Prolactin (ng/mL) (normal range, 2-18 ng/mL) |

8.22 | 16.17 | ↓0.3 |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | ↓28.5 (−2.7 SD) | ↓16.92 (−2.7 SD) | ↓32.4 (−2.58 SD) |

|

TSH (mU/L) (normal range, 0.51–4.3 mU/L) |

4.27 | 3.5 | 2.7 |

|

Fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) (normal range, 80–110 mg/dL) |

↑518 | ↑464.9 | 89.31 |

|

Urea (mg/dL) (normal range, 20-45 mg/dL) |

26 | 24 | 30.9 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) (normal range, 0.57-1.25 mg/dL) |

0.7 | 0.6 | 0.44 |

ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; LH, luteinizing hormone; SD, standard deviation; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Patient 2

A 17-year-old Iraqi boy, the youngest brother of the first patient, was referred to our outpatient clinic with the same skin findings as his older brother except that patient 2's skin lesion extended to the lower back (Fig 2). Skin lesions began at the age of 4 years. He also had bilateral ankle swelling and pain, bilateral hallux valgus deformities, musculoskeletal pain, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus that was diagnosed in early childhood. In addition, he has sensorineural hearing loss, gynecomastia, inguinal lymphadenopathy, corneal arcus, exophthalmos, and growth failure (height for age, −6.23 standard deviation; body mass index for age, −2.13 standard deviation). Examination of the genitalia found firm scrotal masses with a swollen and retracted penis. The patient declined scrotal biopsy. The patient had Tanner pubic hair stage 1. Abdominal ultrasonography found hepatosplenomegaly, and a DXA scan found low BMD (Z-score, −4.3). For summary of the clinical findings and laboratory test results, see Tables I and II.

Fig 2.

Hyperpigmented patches with overlying hypertrichosis symmetrically involving the feet, calves, thighs, and lower back of patient 2.

Patient 3

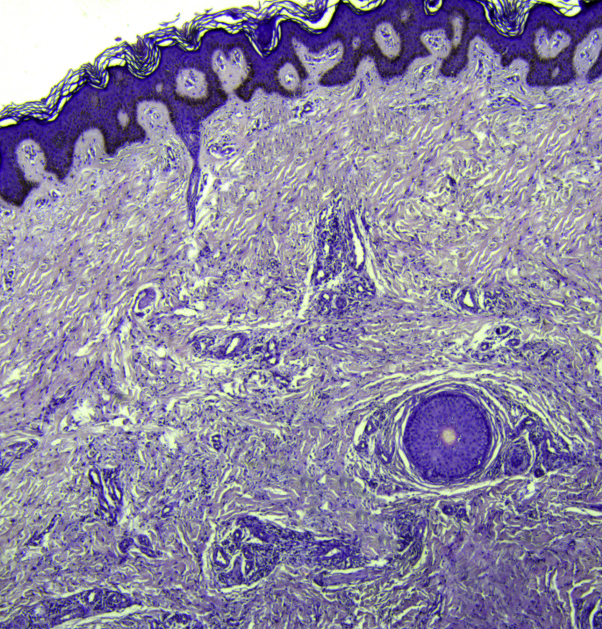

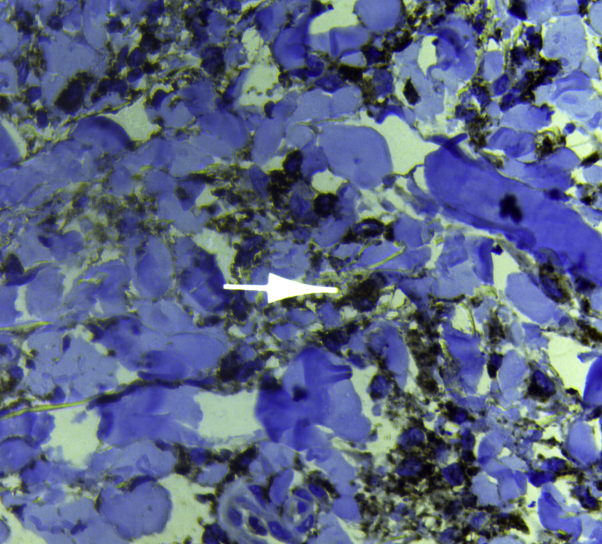

This patient was previously described by the authors,6 but that additional clinical information is reported herein. A 17-year-old Iraqi boy, the son of consanguineous healthy parents, presented to our outpatient clinic with hyperpigmented indurated patches with overlying hypertrichosis involving the inner aspects of the thighs, calves, and ankles (Fig 3) associated with bilateral ankle swelling and pain, hallux valgus, and flexion deformities in the toes (Fig 4) and little fingers. Severe deafness was evident, and the patient communicated by using sign language. He also had gynecomastia, musculoskeletal pain, corneal arcus, exophthalmos, bilateral optic disc swelling, premature graying of the hair, hypospadias, short stature (see Table I), and inguinal lymphadenopathy. According to the parents, the older brother of this patient has bilateral swelling of the feet and deformities of the toes but without skin lesions. A biopsy from the hyperpigmented patches found orthokeratosis, acanthosis, and basal-layer hyperpigmentation in addition to widespread fibrosis and thickened collagen bundles with mononuclear cell infiltrates in the dermis (Fig 5). Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse infiltration of CD68+ histiocytes in the dermis (Fig 6). An abdominal ultrasound examination found mild hepatosplenomegaly, and a DXA scan found low BMD (Z-score, −2.6). Brain magnetic resonance imaging was normal. For a summary of the clinical and laboratory findings, see Tables I and II.

Fig 3.

Hyperpigmented hypertrichotic patches symmetrically involving the inner aspects of the thighs of patient 3.

Fig 4.

Hallux valgus deformities and flexion contractures in the toes of both feet of patient 3. Note the hyperpigmented patches on both feet.

Fig 5.

A biopsy from the hyperpigmented patches of patient 3 shows orthokeratosis, acanthosis, and basal-layer hyperpigmentation, in addition to widespread fibrosis and thickened collagen bundles with mononuclear cell infiltrates in the dermis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain.)

Fig 6.

Immunohistochemistry stain shows diffuse infiltration of CD68+ histiocytes in the dermis.

Discussion

H syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive syndrome affecting multiple organ systems with pathognomonic skin findings.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Here we report on 3 Iraqi patients with characteristic clinical, histopathologic, and laboratory findings of H syndrome. All 3 patients have hyperpigmented indurated patches with overlying hypertrichosis symmetrically involving the lower half of the body associated with other features of H syndrome (Table I). Genetic testing was not performed in the 3 patients because their families refused it. Lack of genetic testing does not affect the diagnosis, as the condition can be diagnosed clinically based on pathognomonic skin findings supported by the presence of other features of this genodermatosis, typical histopathologic features, and the suggestive family history.6 Musculoskeletal abnormalities are prominent features in patients with H syndrome; flexion contractures of the fingers and toes represent the most common feature (affecting 56% of patients), followed by hallux valgus deformities (30%), flat foot/foot deformity (20%), bone fractures (9%), and arthritis (8%).9 In our 3 cases, we have also reported musculoskeletal pain, and low BMD.10 To date, fewer than 120 cases of H syndrome have been reported worldwide. Of these cases, the vitamin D level was only measured in a single case, and it was deficient.11 We have assessed the levels of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in all 3 of our patients. Interestingly, in all these patients, vitamin D levels were markedly decreased, and this decrease is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism (Table I). Furthermore, DXA scans found that all 3 patients have low BMD, which can be attributed to the increased parathyroid hormone levels. These increased levels usually lead to an increase in bone turnover and consequently may cause the loss of bone mass.12 Therefore, we hypothesize that hypovitaminosis D, complicated by secondary hyperparathyroidism may cause some of the musculoskeletal findings in patients with H syndrome, namely, musculoskeletal pain, low BMD, and bone fractures. Therefore, we prescribed vitamin D (ergocalciferol) for all 3 patients until normalization of the levels of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone were achieved after 3 months of treatment. Interestingly, we noticed improvement in some of the musculoskeletal signs and symptoms in all 3 patients. Marked improvement was noted in musculoskeletal pain, and an increase was noted in the bone mineral density documented by DXA scans. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with H syndrome may be caused by malabsorption, which occurs in about 15% of cases. Poor exposure to sunlight may also be a cause, which may result from the impact of the disease on the psychology of the patient and his outdoor physical activities.9,13,14 Chronic inflammation and impaired ability of the skin to produce vitamin D are also possibilities; however, further studies are required to determine the exact cause of vitamin D deficiency in these patients. In patients with H syndrome, vitamin D deficiency might relate to short stature, underlying bone defect, musculoskeletal pain, and low BMD and, if untreated, could cause worsening bony deformities and fractures. It is wise to assess vitamin D levels in all patients with H syndrome, as vitamin D replacement can improve some of their musculoskeletal problems. In patient 2, the low BMD and musculoskeletal pain may also be related to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (low luteinizing hormone and testosterone) or growth hormone deficiency. Furthermore, decreased levels of circulating insulin-like growth factor-1 in all 3 patients may directly affect bone growth and density.15 However, further studies with a larger sample size will be required to arrive at firm conclusions.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Molho-Pessach V., Agha Z., Aamar S. The H syndrome: a genodermatosis characterized by indurated, hyperpigmented, and hypertrichotic skin with systemic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom J.L., Lin C., Imundo L. H syndrome: 5 new cases from the United States with novel features and responses to therapy. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0204-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avitan-Hersh E., Mandel H., Indelman M. A case of H syndrome showing immunophenotye similarities to Rosai–Dorfman disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ee547c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molho-Pessach V., Lerer I., Abeliovich D. The H syndrome is caused by mutations in the nucleoside transporter hENT3. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yesudian P., Sarveswari K.N., Karrunya K.J. H syndrome: a case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:300–302. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_187_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hamdi K.I., Ismael D.K., Qais Saadoon A. H syndrome with possible new phenotypes. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(4):355–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emile J.F., Oussama A., Fraitag S. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672–2681. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-690636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tekin B., Atay Z., Ergun T. H syndrome: a multifaceted histiocytic disorder with hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:1021–1023. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molho-Pessach V., Ramot Y., Camille F. H syndrome: the first 79 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta S., Masatkar V., Mittal A., Khare A.K., Gupta L.K. The H syndrome. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2015;16:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meena D., Chauhan P., Hazarika N. H syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63(1):76. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_264_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serhan E., Holland M.R. Relationship of hypovitaminosis D and secondary hyperparathyroidism with bone mineral density among UK resident Indo-Asians. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(5):456–458. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.5.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simsek E., Simsek T., Eren M. Clinical, histochemical, and molecular study of three Turkish siblings diagnosed with H syndrome, and literature review. Horm Res Paediatr. 2019;91(5):346–355. doi: 10.1159/000495190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaouadi H., Zaouak A., Sellami K. H syndrome: clinical, histological and genetic investigation in Tunisian patients. J Dermatol. 2018;45(8):978–985. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakar S., Rosen C.J., Beamer W.G. Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(6):771–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI15463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]