Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is common in Metabolic Syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2DM), driven by energy imbalance, saturated fats and simple carbohydrates. NAFLD requires screening and monitoring for late complications. Liver fat indices may predict NAFLD avoiding expensive or invasive gold-standard methods, but they are poorly validated for use in interventional settings. Recent data indicate a particular insensitivity to weight-independent liver fat reduction. We evaluated 31 T2DM patients, completing a randomized intervention study on isocaloric high-protein diets. We assessed anthropometric measures, intrahepatic lipid (IHL) content and serum liver enzymes, allowing AUROC calculations as well as cross-sectional and longitudinal Spearman correlations between the fatty liver index, the NAFLD-liver fat score, the Hepatosteatosis Index, and IHL. At baseline, all indices predicted NAFLD with moderate accuracy (AUROC 0.731–0.770), supported by correlation analyses. Diet-induced IHL changes weakly correlated with changes of waist circumference, but no other index component or the indices themselves. Liver fat indices may help to easily detect NAFLD, allowing cost-effective allocation of further diagnostics to patients at high risk. IHL reduction by weight-independent diets is not reflected by a proportional change in liver fat scores. Further research on the development of treatment-sensitive indices is required.

Trial registration: The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02402985.

Subject terms: Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Gastrointestinal diseases, Metabolic disorders, Nutrition disorders

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common metabolic disorder with increasing prevalence1. Paralleling its epidemiological development with type 2 diabetes (T2DM), both manifestations of the Metabolic Syndrome are mainly driven by a low energy expenditure and non-proportionally high energy intake2.

Hepatosteatosis may progress further to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), hepatic fibrosis, hepatic cirrhosis, and primary hepatic malignoma, highlighting the need for prevention and therapy3.

To detect early NAFLD, ultrasound sonography may be helpful, but requires experienced examining personnel and good imaging quality4. Sonoelastography can amplify a first diagnosis by adding information about liver tissue density, but not all causes of liver fibrosis are necessarily linked to high liver fat content allowing misinterpretation5,6. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance-(MR)-based techniques are expensive techniques and either accommodated by x-ray exposure or contraindications to due magnetic fields. Both, CT and MRI (before the era of multi-echo Dixon assessment of proton density fat fraction) provide an only moderate sensitivity and specificity for NAFLD detection and graduation7.

On the other hand, proton MR spectroscopy (1H-MRS) indeed measures tissue lipid content, but is mainly used in clinical studies due to high instrumental costs. Liver biopsies provide a highly specific measurement of intrahepatic lipid (IHL) amount, but are prone to misinterpretation in cases of heterogeneous fat distribution. Also, there is a significant risk of liver injury, bleeding, bile leakage and further complications.

To assess and monitor NAFLD with low costs in every subject at risk, several NAFLD scores have been developed. The fatty liver index (FLI) uses markers of obesity (body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference), dyslipidemia (triglycerides (TG)), and liver injury (gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and correlates with liver fat content, predicting the majority of NAFLD cases8. However, waist circumference and visceral obesity seem to be the main factors in its prediction models9,10. The NAFLD-liver fat score (NAFLD-LFS) requires assessment of fasting insulin and transaminases as well as the subjects’ classification regarding the Metabolic Syndrome. The prediction quality of the NAFLD-LFS is comparable to the FLI11 and both indices are designed and validated for Caucasian populations. Genetic markers such as P184L in the Patatin-Like Phospholipase Domain-Containing Protein 3 (PNPLA3) gene have been shown to improve their power11,12. In Asian cohorts, the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) was demonstrated as a suitable NAFLD prediction tool13, but ethnicity appears to be a relevant factor of those prediction models14. This led to the development of some more indices in the past, focusing on various ethnicities15–17.

These three indices have been shown to be useful in a population-wide perspective in order to estimate NAFLD-associated mortality18.

All NAFLD scores are only moderate in sensitivity and specificity, with respect to the also-flawed sonography19 and under validation by biopsy20. NAFLD in children is possibly easier to predict, as adiposity and metabolic disorder are more purely involved in disease progression in this sub-group, excluding ageing and long-term toxicity of specific environmental factors21,22. Sonography examination is highly dependent on examiner’s expertise and ranks inferior to liver fat indices23. Also, no serum marker has been demonstrated to outrank conventional liver fat indices24,25.

As an important factor, sex affects some components of NAFLD indices, implying differences in the predictive quality for men and women26,27. However, only the HSI accounts for these differences13.

Additionally, HSI and FLI seem to fail to sufficiently predict NAFLD in subjects with overt T2DM, possibly due to interactions with typical medications in these patients, wide-range daily fluctuations of fasting glucose or lower discriminative range of the HSI. This is plausible, as literally all subjects with overt T2DM fulfill a major criterion of the index with no regard to their liver status13.

Furthermore, there is almost no published data on the value of NAFLD indices in longitudinal settings. It is unclear, whether changes in NAFLD scores mirror changes in actual liver fat content. Lipid parameters are not yet sufficiently investigated to be of use during the monitoring process21. NAFLD-LFS and FLI showed an only weak to moderate performance as monitoring tools within low-fat lifestyle intervention trials12,28,29. On the other hand, their usefulness within a low-carb diet could not be shown29. Missing correlation between change of liver fat indices and change of actual IHL was attributed to the missing correlation between weight change and liver fat reduction. Similar effects need to be expected from glitazones, but also from dietary approaches with poly-unsatured fatty acids, which act independently of weight loss30. A recent short-term trial on high-protein diets has demonstrated, that this approach is another way to reduce liver fat without relevant loss in body weight31,32.

As liver fat reduction does not require weight loss, more data is needed to evaluate, if liver fat scores can reflect changes of IHL content independently of the therapeutic approach.

Therefore, we investigate the statistical relation between changes in three liver fat scores in a human lifestyle intervention trial, featuring two isocaloric diets. For our analysis, assessments of liver fat content by 1H-MRS and liver fat scores on the basis of anthropometric measurements and fasted blood samples are available.

Methods

Data for this publication are extracted from the lifestyle intervention trial, registered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02402985 (submitted on 4th February 2015, first posted on 31st March 2015). This randomized parallel-designed trial compared two isocaloric six-week dietary interventions with either plant- or an animal-based high-protein diet in subjects with T2DM. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of the University of Potsdam approved the study protocol. Recruitment for this study started in September 2013 and was completed in March 2015. All subjects provided their informed consent prior to participation. Data from the trial, including a detailed section about the study protocol, was already published elsewhere31,32.

At baseline, the participants of the study underwent fasting blood sampling, a mixed meal tolerance test, full anthropometry (body weight, height, abdominal circumferences, bio-impedance analysis) and medical examination. Study volunteers were also subjected to liver 1H-MRS on a 1.5 T whole body imager (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) according to pre-published specifications33. In brief, a single voxel STimulated Echo Acquisition Mode (STEAM) technique with short echo time (TE = 10 ms) and long repetition time (TR = 4 s) was applied and the volume of interest (30 × 30 × 20 mm3) was placed in the posterior part of segment 7. Ratio of the integral of methylene and methyl resonances (lipids) and water + lipids was calculated to determine IHL.

Data from this publication is restricted to subjects with complete data sets on liver fat content and liver fat scores (per-protocol analysis on diet phase completers with no respect to dietary in-/compliance). Subjects with severe cardiopulmonary, hepatic, metabolic, psychiatric, infectious or inflammatory disease are excluded from the entire study. Also, participants with increased ethanol intake (men: above 30 g per day; women: above 20 g per day) are not part of the presented data set.

After screening, inclusion and baseline assessment with 1H-MRS, subjects were 1:1-randomised to one of two dietary regimes with comparable isocaloric nutrient distribution of 25–30% relative energy intake (EI%) of protein, 40 EI% of carbohydrates, 30–35 EI% of fat, but differing in their protein source: animal protein (dairy/meat) or legumes. Randomisation was done by non-clinical personnel by group matching for age, sex, body mass index, hemoglobin A1c, and glucose-lowering drugs using a random number generator. Dietary intervention (supplementation with neutrally labelled high-protein food products of similar appearance) was conducted for 6 weeks. All assessments from the baseline visit were repeated after that time period.

Subjects were instructed not to change physical activity.

Animal and plant protein diet showed a comparable outcome with respect to overall performance including liver fat reduction, both diet groups were treated as combined cohort for this analysis31,32.

Statistical analysis entails calculation of area-under-the-responder-operator-curves (AUROC) for the prediction of NAFLD by FLI, NAFLD-LFS and HSI at baseline. FLI, NAFLD-LFS and HSI were calculated according to their first publication8,11,13. Also, Spearman correlations were used to evaluate cross-sectional prediction of NAFLD at baseline and longitudinal monitoring of NAFLD during the diet phase.

Additional correlation analyses were performed to elucidate potential reasons or mechanisms for diet-dependent results. SPSS 25.0 was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

31 subjects of the study with full data on IHL and liver fat indices were selected for the presented data set. Baseline characteristics for the cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Parameter | (n = 31) |

| Age (years) | 65 ± 6 |

| Sex (male/female) | 19 m/12 f |

| Liver fat content (MR-S; %) | 15.4 ± 9.8 |

| FLI | 74 ± 23 |

| NAFLD-LFS | 0.54 ± 1.16 |

| HSI | 40 ± 4 |

| Body weight (kg) | 89.4 ± 14.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.6 ± 3.7 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 102.9 ± 10.9 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 9.48 ± 6.29 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.70 ± 0.59 |

| AST (U/ml) | 25 ± 9 |

| ALT (U/ml) | 28 ± 10 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| GGT (U/ml) | 44 ± 26 |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase, FLI fatty liver index, HSI Hepatosteatosis Index, NAFLD-LFS Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-liver fat score; no significant differences between both groups.

NAFLD prediction and correlation at baseline

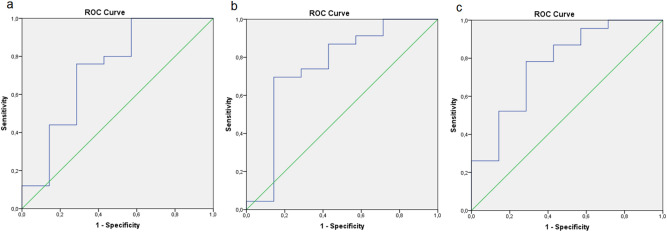

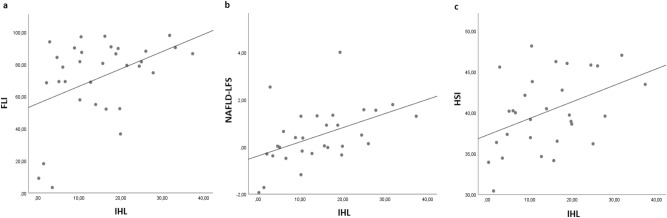

NAFLD prediction by FLI, NAFLD-LFS and HSI is comparable to their first publication8,11,13, resulting in AUROC values of 0.731 for FLI, 0.752 for NAFLD-LFS and 0.770 for HSI in the entire cohort, respectively (Fig. 1A–C). Accordingly, correlations between IHL and each of the three liver fat indices were significant at baseline (Fig. 2A–C).

Figure 1.

AUROC representation of NAFLD prediction by FLI (a), NAFLD-LFS (b) and HSI (c); the analyses show AUROC values of 0.731 (FLI), 0.752 (NAFLD-LFS) and 0.770 (HSI).

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis between liver fat indices and IHL at baseline; FLI = fatty liver index, HSI = Hepatosteatosis Index, IHL = intrahepatic lipids, NAFLD-LFS = non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-liver fat score; (a) IHL ~ FLI; rho = 0.351. p = 0.049; (b) IHL ~ NAFLD-LFS; rho = 0.537, p = 0.002; (c) IHL ~ HSI; rho = 0.393, p = 0.032.

Correlations between change of index values and interventional 1H-MRS data

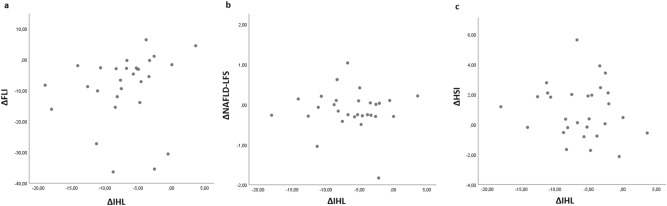

As reported in our previous publication, liver fat reduction in these 31 subjects was very strong (6.7 ± 5.0%-pts.), but was hardly explained by the very limited weight loss of 2.1 ± 1.7 kg31. In this interventional perspective there was no significant correlation between changes of IHL and changes of NAFLD-LFS or HSI, but we report a weak, trendwise association between change of IHL and change of FLI. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis with changes of liver fat indices and IHL; FLI = fatty liver index, HSI = Hepatosteatosis Index, IHL = intrahepatic lipids, NAFLD-LFS = non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-liver fat score; (a) IHL ~ FLI; rho = 0.342. p = 0.069; (b) IHL ~ NAFLD-LFS; rho = − 0,058, p = 0.765; (c) IHL ~ HSI; rho = − 0.049, p = 0.800.

Correlations between changes of index parameters and 1H-MRS based IHL data

Correlation analysis between change of actual IHL content and change of single elements of the liver fat scores revealed just one significant correlation—for the reduction of waist circumference. The similarly weak correlation with weight loss failed to achieve statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis on interventional changes.

| Correlation between change of liver fat content (MR-S) and change of … | (n = 31) |

| Body weight (kg) | Rho = 0.347, p = 0.056 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | Rho = 0.409, p = 0.022 * |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | Rho = − 0.026, p = 0.890 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | Rho = 0.299, p = 0.103 |

| AST (U/ml) | Rho = 0.091, p = 0.626 |

| ALT (U/ml) | Rho = 0.200, p = 0.298 |

| AST/ALT ratio | Rho = − 0.133, p = 0.490 |

| GGT (U/ml) | Rho = 0.219, p = 0.254 |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Splitting any of the above-mentioned analyses by diet group did not lead to numerically different results (data not shown).

Discussion

Liver fat scores are an easy and cheap tool to assess NAFLD status in metabolic research, but also in clinical practice. These tools might save time, monetary personal and technical resources, as they are suitable for any kind of patient and do not require expensive body imaging.

However, previous data on the prediction quality of these scores show a limited predictive performance34. Within the present study, there is additional support for the use of these indices in cross-sectional settings.

Similar to a recent publication on a hypocaloric high-protein low-carb diet, the current analysis in subjects undergoing an isocaloric high-protein diet also reveals poor performance in a longitudinal approach29. Liver fat reduction by this particular diet, independently of weight loss, is not reflected by any liver fat score with satisfying precision. IHL reduction in low-fat diets—with a consistent dependency of metabolic improvement on weight loss—seems to be the only dietary NAFLD treatment, that can be monitored by liver fat scores12,28.

By correlation analysis we showed in our T2DM sample, that combined liver fat scores do not sufficiently reflect the actual change in IHL. While the FLI may provide a weak correlation in a larger data set, both NAFLD-LFS and HSI completely failed to mirror the changes in liver fat content. Apparently, the FLI outranks these indices as all FLI elements—body weight, waist circumference, triglycerides and GGT—are those single parameters which are most strongly connected to change of IHL. Among all liver enzymes, GGT is the most sensitive liver parameter for prediction of NAFLD and its sequelae35–37 Insulin levels—being part of the badly performing NAFLD-LFS—may not necessarily reflect a metabolic improvement, especially in the context of T2DM patients with primarily reduced insulin secretion capacity, who often lack NAFLD11,38. The HSI was developed for patients of Asian ethnicity, maybe limiting its application to Caucasian patients13.

Most individual index parameters do not correlate with 1H-MRS derived change of liver fat. The strongest connection between change of liver fat and other single anthropometabolic outcomes was seen with waist circumference. Apparently, in our high-protein setting, both visceral and hepatic fat depots are reduced simultaneously31. However, change in body weight does not relevantly correlate with change in IHL in the present cohort. As measures of obesity are a major component of all liver fat scores, limited weight loss might be the crucial factor in missing correlation between change of liver fat scores and change of IHL. In our data set of the isocaloric LeguAN study, we observed a rather minor weight loss of 2.1 ± 1.7 kg over an intervention period of six weeks. Most possibly, the same finding as ours could be present in isocaloric diets with improved dietary fat composition or in pharmaceutical treatments (glitazones, gliflozines), which have been shown to reduce liver fat independently of weight loss. As a strength of our analysis, the observed liver fat reduction is marked, especially given the very moderate weight loss. Thus, we can clearly show the dissociation of adiposity and NAFLD as metabolic outcomes of the study, but also as aspects of liver fat indices.

In comparison to a recently published analysis on IHL monitoring in a low-carb diet, correlations with several metabolic parameters in our cohort were at least similar in direction, if not magnitude. Especially changes in ALT and IHL reduction correlated under low-carb, but not low-fat conditions29. High-protein diets seem to beneficially affect lipid levels, including triglycerides, and all transaminase levels. Missing correlation between these changes and change of IHL might indicate additional actions beyond mere steatosis. Possibly, transaminase levels in these patients do also reflect a certain degree of inflammation (NASH) or fibrosis, which is improved in parallel. The possibility of dietary effects even on high-stage fibrosis has been discussed recently39.

New prediction scores might include parameters with higher prediction quality and specificity, such as ferritin40.

Some limitations have to be addressed for the present study. Our data set provides a moderate statistical power compared to other studies on this issue. However, it is the first publication on subjects with overt T2DM.

Further, we are unable to fully clarify the reasons for missing comparability of longitudinal correlations between liver fat scores and MR-based liver fat values in different diets. As shown in recent publications, liver fat reduction can be achieved in accompaniment of highly variable metabolic improvements, depending on type of diet. This diet-specific interaction also entails linkage of IHL reduction and total weight loss in low-fat diets, but not low-carb or high-protein diets29.

Conclusively, with the present study, we underline the good predictive properties of FLI, NAFLD-LFS and HSI before a dietary intervention in subjects with overt T2DM by both AUROC analysis and Spearman correlation. However, liver fat reduction is not accompanied by correlating liver fat scores.

Liver fat indices need to be used cautiously, especially when assessing changes in different interventional settings. More research is needed to elaborate effects of specific diets on metabolic components and blood parameters that could be used for the design of a liver fat index.

Acknowledgements

We thank our participants, our technical assistants and study nurses, both in the clinical ward as well as in the laboratories, for their help in the acquisition of the study data and their crucial work with the participants.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMBF

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (German Federal Ministry for Education and Research)

- BMEL

Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (German Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture)

- BMI

Body-mass index

- CT

Computed tomography

- DZD

Deutsches Zentrum für Diabetesforschung (German Center for Diabetes Research)

- EI

Energy intake

- FLI

Fatty liver index

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyltransferase

- HSI

Hepatic steatosis index

- IHL

Intrahepatic lipids

- MRS

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NAFLD-LFS

NAFLD-liver fat score

- NASH

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PNPLA3

Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3

- STEAM

STimulated echo acquisition mode

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TG

Triglycerides

Author contributions

S.K. and M.M. wrote the paper, M.M. and S.S. conducted the experiments by dietary consultation, collected and interpreted according data, S.H. performed medical examinations and supervision for the participants, collected and interpreted according data, J.M., S.R. and J.H. collected and interpreted data with respect to specific laboratory analyses and MR spectroscopy, S.K. and M.M. performed the statistical analysis, S.H., O.P.R. and A.F.H.P. designed the study, all authors read and revised the manuscript, contributed to discussion and approved the final version of this paper. S.K. is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole and serves as guarantor of this work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. General funding for this study was provided by the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), which itself is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), and by the German Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture (BMEL). The funding parties were not involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and writing of this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Stefan Kabisch and Mariya Markova.

References

- 1.Tomah S, Alkhouri N, Hamdy O. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: where do Diabetologists stand? Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;6:9. doi: 10.1186/s40842-020-00097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruissen MM, Mak AL, Beuers U, Tushuizen ME, Holleboom AG. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multidisciplinary approach towards a cardiometabolic liver disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183:R57–R73. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grazia P, Ciro C, Antonia G, Federica S, Salvatore P. The relevance of noninvasive tools to assess fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020;26:3928–3938. doi: 10.2174/1381612826666200521133307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraioli G, Soares Monteiro LB. Ultrasound-based techniques for the diagnosis of liver steatosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019;25(40):6053–6062. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i40.6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Lugari S, Lonardo A, Francica G. A critical appraisal of the use of ultrasound in hepatic steatosis. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;13(7):667–681. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1621164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pu K, Wang Y, Bai S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) as a non-invasive test for steatosis in suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0961-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwenzer NF, Springer F, Schraml C, Stefan N, Machann J, Schick F. Non-invasive assessment and quantification of liver steatosis by ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance. J. Hepatol. 2009;51(3):433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedogni G, Bellentani S, Miglioli L, Masutti F, Passalacqua M, Castiglione A, Tiribelli C. The Fatty liver index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motamed N, Sohrabi M, Ajdarkosh H, Hemmasi G, Maadi M, Sayeedian FS, Pirzad R, Abedi K, Aghapour S, Fallahnezhad M, Zamani F. Fatty liver index vs waist circumference for predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22(10):3023–3030. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grotti Clemente AP, Molin Netto BD, Ganen AP, et al. Cut-off values of visceral adiposity to predict NAFLD in Brazilian obese adolescents. J. Nutr. Metabol. 2013;2013:724781. doi: 10.1155/2013/724781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A, Sevastianova K, Bergholm R, Johansson LM, Lundbom N, Rissanen A, Ridderstråle M, Groop L, Orho-Melander M, Yki-Järvinen H. Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):865–872. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantartzis K, Rettig I, Staiger H, Machann J, Schick F, Scheja L, Gastaldelli A, Bugianesi E, Peter A, Schulze MB, Fritsche A, Häring HU, Stefan N. An extended fatty liver index to predict non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43(3):229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, Lee CH, Yang JI, Kim W, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Cho SH, Sung MW, Lee HS. Hepatic steatosis index: a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010;42(7):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia MF, Yki-Järvinen H, Bian H, Lin HD, Yan HM, Chang XX, Zhou Y, Gao X. Influence of ethnicity on the accuracy of non-invasive scores predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0160526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Xu C, Xun Y, Lu Z, Shi J, Yu C, Li Y. ZJU index: a novel model for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16494. doi: 10.1038/srep16494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatt SP, Misra A, Nigam P, Guleria R, Pasha MA. Phenotype body composition and prediction equations (Indian Fatty liver index) for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-diabetic asian indians: a case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birjandi M, Ayatollahi SM, Pourahmad S, Safarpour AR. Prediction and diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and identification of its associated factors using the classification tree method. Iran Red Crescent Med. J. 2016;18(11):e32858. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.32858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Liver fat scores predict liver disease mortality in the United States population. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;48(9):1003–1016. doi: 10.1111/apt.14967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahl S, Straßburger K, Nowotny B, Livingstone R, Klüppelholz B, Keßel K, Hwang JH, Giani G, Hoffmann B, Pacini G, Gastaldelli A, Roden M. Comparison of liver fat indices for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedchuk L, Nascimbeni F, Pais R, Charlotte F, Housset C, Ratziu V. LIDO Study Group. Performance and limitations of steatosis biomarkers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;40(10):1209–1222. doi: 10.1111/apt.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang HX, Xu XQ, Fu JF, Lai C, Chen XF. Predicting hepatic steatosis and liver fat content in obese children based on biochemical parameters and anthropometry. Pediatr. Obes. 2015;10(2):112–117. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koot BG, van der Baan-Slootweg OH, Bohte AE, Nederveen AJ, van Werven JR, Tamminga-Smeulders CL, Merkus MP, Schaap FG, Jansen PL, Stoker J, Benninga MA. Accuracy of prediction scores and novel biomarkers for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(3):583–590. doi: 10.1002/oby.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantero I, Elorz M, Abete I, et al. Ultrasound/elastography techniques, lipidomic and blood markers compared to magnetic Resonance Imaging in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease adults. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019;16(1):75–83. doi: 10.7150/ijms.28044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orešič M, Hyötyläinen T, Kotronen A, Gopalacharyulu P, Nygren H, Arola J, Castillo S, Mattila I, Hakkarainen A, Borra RJ, Honka MJ, Verrijken A, Francque S, Iozzo P, Leivonen M, Jaser N, Juuti A, Sørensen TI, Nuutila P, van Gaal L, Yki-Järvinen H. Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty-liver disease and liver fat content by serum molecular lipids. Diabetologia. 2013;56(10):2266–2274. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2981-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guiu B, Crevisy-Girod E, Binquet C, Duvillard L, Masson D, Lepage C, Hamza S, Krausé D, Verges B, Minello A, Cercueil JP, Hillon P, Petit JM. Prediction for steatosis in type-2 diabetes: clinico-biological markers versus 1H-MR spectroscopy. Eur. Radiol. 2012;22(4):855–863. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirkalali B, Poustchi H, Keyvani H, Khansari MR, Ajdarkosh H, Maadi M, Sohrabi MR, Zamani F. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its predictors in North of Iran. Iran J. Public Health. 2014;43(9):1275–1283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim G, Lee Y, Park YM, et al. Use of a diabetes self-assessment score to predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Medicine. 2015;94(27):e1103. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keating SE, Parker HM, Hickman IJ, Gomersall SR, Wallen MP, Coombes JS, Macdonald GA, George J, Johnson NA. NAFLD in clinical practice: Can simple blood and anthropometric markers be used to detect change in liver fat measured by 1H-MRS? Liver Int. 2017;37(12):1907–1915. doi: 10.1111/liv.13488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabisch S, Bäther S, Dambeck U, Kemper M, Gerbracht C, Honsek C, Sachno A, Pfeiffer AFH. Liver fat scores moderately reflect interventional changes in liver fat content by a low-fat diet but not by a low-carb diet. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):E157. doi: 10.3390/nu10020157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjermo H, Iggman D, Kullberg J, Dahlman I, Johansson L, Persson L, Berglund J, Pulkki K, Basu S, Uusitupa M, Rudling M, Arner P, Cederholm T, Ahlström H, Risérus U. Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat lipoproteins and inflammation in abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;95(5):1003–1012. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markova M, Pivovarova O, Hornemann S, Sucher S, Frahnow T, Wegner K, Machann J, Petzke KJ, Hierholzer J, Lichtinghagen R, Herder C, Carstensen-Kirberg M, Roden M, Rudovich N, Klaus S, Thomann R, Schneeweiss R, Rohn S, Pfeiffer AF. Isocaloric diets high in animal or plant protein reduce liver fat and inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):571–585.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sucher S, Markova M, Hornemann S, Pivovarova O, Rudovich N, Thomann R, Schneeweiss R, Rohn S, Pfeiffer AFH. Comparison of the effects of diets high in animal or plant protein on metabolic and cardiovascular markers in type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017;19(7):944–952. doi: 10.1111/dom.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machann J, Thamer C, Schnoedt B, Stefan N, Haring HU, Claussen CD, Fritsche A, Schick F. Hepatic lipid accumulation in healthy subjects: a comparative study using spectral fat-selective MRI and volume-localized 1H-MR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55(4):913–917. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahl S, Straßburger K, Nowotny B, et al. Comparison of liver fat indices for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii H, Doi H, Ko T, Fukuma T, Kadono T, Asaeda K, Kobayashi R, Nakano T, Doi T, Nakatsugawa Y, Yamada S, Nishimura T, Tomatsuri N, Sato H, Okuyama Y, Kimura H, Kishimoto E, Nakabe N, Shima T. Frequently abnormal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity is associated with future development of fatty liver: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01369-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajput R, Ahlawat P. Prevalence and predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in prediabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(5):2957–2960. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Noninvasive fatty liver markers predict liver disease mortality in the U.S. population. Hepatology. 2016;63(4):1170–1183. doi: 10.1002/hep.28390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, Strom A, Bönhof GJ, Karusheva Y, Antoniou S, Bódis K, Markgraf DF, Burkart V, Müssig K, Hwang JH, Asplund O, Groop L, Ahlqvist E, Seissler J, Nawroth P, Kopf S, Schmid SM, Stumvoll M, Pfeiffer AFH, Kabisch S, Tselmin S, Häring HU, Ziegler D, Kuss O, Szendroedi J, Roden M. German Diabetes Study Group. Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):684–694. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yki-Järvinen H. Nutritional modulation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Nutrients. 2015;7(11):9127–9138. doi: 10.3390/nu7115454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jung JY, Shim JJ, Park SK, Ryoo JH, Choi JM, Oh IH, Jung KW, Cho H, Ki M, Won YJ, Oh CM. Serum ferritin level is associated with liver steatosis and fibrosis in Korean general population. Hepatol Int. 2019;13(2):222–233. doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9892-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]