Summary

Ablation of Slc22a14 causes male infertility in mice, but the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Here, we show that SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter localized at the inner mitochondrial membrane of the spermatozoa mid-piece and show by genetic, biochemical, multi-omic, and nutritional evidence that riboflavin transport deficiency suppresses the oxidative phosphorylation and reprograms spermatozoa energy metabolism by disrupting flavoenzyme functions. Specifically, we find that fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) is defective with significantly reduced levels of acyl-carnitines and metabolites from the TCA cycle (the citric acid cycle) but accumulated triglycerides and free fatty acids in Slc22a14 knockout spermatozoa. We demonstrate that Slc22a14-mediated FAO is essential for spermatozoa energy generation and motility. Furthermore, sperm from wild-type mice treated with a riboflavin-deficient diet mimics those in Slc22a14 knockout mice, confirming that an altered riboflavin level causes spermatozoa morphological and bioenergetic defects. Beyond substantially advancing our understanding of spermatozoa energy metabolism, our study provides an attractive target for the development of male contraceptives.

Keywords: SLC22A14 transporter, male infertility, riboflavin, fatty acid β-oxidation, energy metabolism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Slc22a14 deficiency results in decreased sperm motility and male infertility

-

•

Slc22a14 ablation disrupts fatty acid β-oxidation and flavoenzyme activity

-

•

Slc22a14 is a riboflavin transporter located at inner mitochondrial membrane in sperm

Long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation is an important energy source during epididymal maturation of spermatozoa. Kuang et al. show that Slc22a14 is a riboflavin transporter located at the inner mitochondrial membrane. Slc22a14 deficiency in the spermatozoa mid-piece disrupts the riboflavin transport and subsequently alters flavoenzyme-mediated bioenergetic metabolism, resulting in male infertility.

Introduction

Increasing evidence has indicated that solute carrier (SLC) family transporters are critical in cellular nutrient and metabolite homeostasis and contribute to the regulation of energy production (Chen et al., 2014; César-Razquin et al., 2015; Nigam, 2015; Yoneshiro et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Song et al., 2019; Koepsell, 2020). Among them, SLC22A14 has been characterized as an organic cation transporter-like protein and is one of the candidate genes for male fertility (Runkel et al., 2008). Work on SLC22A14 demonstrates its expression in the spermatozoa principal piece and shows that Slc22a14 ablation induces male infertility in mice (Maruyama et al., 2016). Medically, ejaculated spermatozoa samples of idiopathic asthenozoospermia patients have revealed significantly lower SLC22A14 levels than fertile control individuals (Huo et al., 2017). These manifestations together support that SLC22A14 critically participates in male fertility. However, the specific biological function and substrate of SLC22A14 have not yet been elucidated, and this protein has been referred to as an “orphan” transporter (Koepsell, 2013).

Spermatozoa are highly motile, and their continuous motility indicates an exceptionally high demand for adenosine triphosphate (ATP), both in epididymal and ejaculated spermatozoa (Piomboni et al., 2012). ATP is generated in the compartmentalized metabolic pathways by both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in spermatozoa, with glycolysis occurring in the fibrous sheath of the principal piece and head, and OXPHOS occurring in mitochondria that are localized exclusively in the mid-piece of flagellum (Buffone et al., 2012; Ferramosca and Zara, 2014). In spermatozoa, the glycolytic enzymes are localized at the fibrous sheath of the principal piece, which is relatively closer than the mid-piece to the site of motility-related ATP utilization. However, there are great controversies about which pathway may represent the primary route used by spermatozoa for ATP production. Although many studies have examined glycolysis as an energy source for mammalian spermatozoa motility (Turner, 2006; Storey, 2008; Mukai and Travis, 2012; Ferramosca and Zara, 2014), when glycolysis is inhibited or spermatozoa from many species stays in sugar-free media, proper functioning and motility of spermatozoa remains intact, although the sustainability and vigor of such motility may not be adequate for optimal fertilization (Amaral et al., 2013a, Ford, 2006; du Plessis et al., 2015), implying that other energy sources beside glycolysis or carbohydrate must be available to support spermatozoa energy production.

To establish a contribution for OXPHOS in motility-related ATP production, it would be useful to prove whether the ATP generated in the mitochondria of mid-piece can be conveyed rapidly and in sufficient quantity down the entire length of the principal piece. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that pure diffusion from the mitochondrion is likely to be adequate for species with relatively small spermatozoa (Ford, 2006; du Plessis et al., 2015). It is also notable that mitochondria membrane potential is positively correlated with both spermatozoa motility and fertilization ability (Paoli et al., 2011). Beside glycolysis, fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) is also implicated in energy production during spermatozoa maturation in the epididymis (Chauvin et al., 2012; Asghari et al., 2017). Fatty acids and long polyenes can be effectively transported from Sertoli cells to germ cells in the testis of rats (Rato et al., 2012). One study characterized the subcellular proteome of human spermatozoa tails and revealed that fatty acid metabolism might be more predominant than previously thought (Amaral et al., 2013b); another study using metabolomics approaches has indicated that not only the carbohydrate pathway but also lipid and lipoprotein pathways are the most significantly enriched ones in human spermatozoa (Paiva et al., 2015). Thus, fatty acid metabolism may actively participate in spermatozoa energy metabolism and motility. Nevertheless, any specific contribution of FAO and/or relevant modulators in spermatozoa remains uncharacterized, and few studies have examined the roles of FAO in spermatozoa quality and male fertility.

In the present study, we characterized the essential functions of SLC22A14 in bioenergetic pathways of epididymal spermatozoa. After observing that Slc22a14 deficiency causes spermatozoa motility defects and male infertility, we found that Slc22a14 knockout (KO) spermatozoa exhibited severely reduced ATP levels. We subsequently discovered the impacts of SLC22A14 on bioenergetic pathways generally and fatty acid metabolism in particular, based on untargeted metabolomics, lipidomics, and isotope-labeling experiments. Specifically, we detected elevated free fatty acid (FFA) and triacylglyceride (TAG) accumulation in Slc22a14-deficient spermatozoa. Biochemically, we found that SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) of spermatozoa and established that disruption of riboflavin transport by SLC22A14 caused decreased flavoenzyme activity, which explained the metabolic reprogramming and defective FAO in our untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics analyses. Finally, and orthogonally confirming the essentiality of riboflavin to normal spermatozoa development, spermatozoa from wild-type (WT) mice fed a riboflavin-deficient diet had similar defects in motility, morphology, and bioenergetic metabolism with Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. Thus, our study suggests that Slc22a14 KO in the spermatozoa mid-piece disrupted the riboflavin transport and subsequently altered flavoenzyme-mediated bioenergetic metabolism, resulting in male infertility.

Results

Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa show reduced motility and angulated flagellum and result in infertility of male mice

Slc22a14 is specifically expressed in testis of both human and mouse (Figure 1A), and the protein this gene encodes is highly conserved among diverse mammalian species (Figure S1A). The Slc22a14 mRNA level in testis peaks at the sexually mature stage (Figure S2A). To elucidate the physiological functions of SLC22A14, we generated a mouse model for male infertility based on CRISPR-Cas9 KO of the Slc22a14 locus (Figures 1B and S2B). Although infertile (Figure 1C), Slc22a14 KO male mice exhibited normal sexuality (Figures S2C and S2D) and testis development (Figure S2E). Spermatozoa flagellum deformation occurred in the caudal epididymal stage in 77% of the Slc22a14 KO mice (Figures S2F and S2G). To better characterize the observed morphology of Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were conducted. Consistently, spermatozoa from Slc22a14 KO mice showed angulated flagellum at the junction of mid-piece and principal piece (Figure 1D). Transverse sections of two flagellar pieces enclosed by the same flagellar membrane mark the presence of hairpin bending in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 1E). Notably, and consistent with a previous report about Slc22a14 KO mice (Maruyama et al., 2016), we detected no overt abnormalities in spermatogenesis or in spermatozoa counts (Figures S2H and S2I).

Figure 1.

Slc22a14 KO results in dysregulated spermatozoa motility, deformities, and infertility in male mice

(A) Slc22a14 mRNA levels in mouse and human tissues.

(B) Map of Slc22a14 KO mouse.

(C) Fertility was analyzed by mating males with WT females using standard methods (n = 8).

(D) SEM (i and iii) and TEM (ii and iv) imaging of spermatozoa showing the morphology of normal spermatozoa flagellum (top), in contrast to the angulated flagellum (bottom) in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa.

(E) TEM imaging of caudal epididymis showing a mature flagellum (blue arrows) of a WT spermatozoa in comparison with a hairpin bending (red arrows) of Slc22a14 KO flagellum.

(F and G) IVF with cumulus-intact oocytes (F). Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa cannot fertilize cumulus-intact oocytes, even when exposed to zona pellucida with artificial assistance; they cannot penetrate the zona pellucida (G).

(H) The IVF success rates of male mice were analyzed with cumulus cells (n = 3).

(I) Birth rates assessed by ICSI test (n = 4).

(J) Immunofluorescence staining of sp56, an acrosome marker of epididymal spermatozoa. Blue, DAPI; red, sp56.

(K) A CASA system was used to measure spermatozoa motility parameters. VAP, average path velocity; VSL, straight-line velocity; VCL, curvilinear velocity; ALH, amplitude of lateral head displacement; BCF, beat cross frequency; STR, straightness of cell track; LIN, linearity of cell track (n = 5).

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

See also Figures S1–S3.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) testing revealed that spermatozoa from Slc22a14 KO males were unable to penetrate and disperse cumulus cells efficiently (Figure 1F). Even though Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa can touch the zona pellucida in the two-cell stage, these spermatozoa cannot successfully penetrate the zona pellucida to fertilize the oocytes (Figures 1G and 1H). Furthermore, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) analysis indicated that Slc22a14 KO induced no obvious DNA damage in spermatozoa (Figure 1I). It is known that at least two critical events propel spermatozoa to disperse the cumulus cells, namely, release of acrosin from intact acrosome (Ferrer et al., 2016) and motility of the spermatozoa flagellum (Kim et al., 2008). We, therefore, conducted co-immunofluorescent staining in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa and found no significant defects in spermatozoa acrosome formation (Figures 1J and S3A). Besides, spermatozoal acrosome reaction (AR) was also assessed in vitro, indicating a normal development of acrosome function in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figures S3B–S3D). However, an analysis based on the computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) system revealed that caudal epididymal spermatozoa motility is severely reduced in Slc22a14 KO mice (Figure 1K).

Slc22a14 KO disrupts spermatozoa energy metabolism by reducing TCA cycle activity and yet increasing glycolytic pathway activity

Moreover, calcein-AM/propidium iodide (Pi) double staining results showed a high viability of 94.46% ± 1.39% in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa, with no significant difference compared to that of 94.49% ± 1.95% in WT (Figures 2A and S3E). Recalling the exceptionally high energy demands for spermatozoa motility, it is highly conspicuous that we observed significantly reduced ATP levels in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with those in the WT (Figure 2B). Further suggesting disrupted energy metabolism, 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining revealed significant elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figures 2C and S3F). As mitochondria are the predominant source for both cellular energy and ROS, we measured mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) based on JC-1 staining and found that compared with WT, the MMP was significantly lower in the Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figures 2D and S3G), although there were no obvious morphological defects in spermatozoal mitochondria (Figure S3H). These results collectively support the hypothesis that SLC22A14 might function in spermatozoa energy metabolism.

Figure 2.

Knockout of Slc22a14 disrupts spermatozoa energy production, resulting in reduced TCA cycle but elevated glycolytic pathway activity

(A) The rates of undamaged (calcein [+]/ Pi [−]), damaged (calcein [+]/ Pi [+]), and dead spermatozoa (calcein [−]/ Pi [+]) were calculated and analyzed. Quantification of calcein/Pi double staining in spermatozoa (n = 3).

(B) ATP generation from caudal epididymal spermatozoa (n = 4).

(C) Intracellular ROS levels in spermatozoa were assayed using the dye DCFH-DA and analyzed (n = 5).

(D) The MMP of spermatozoa was determined using JC-1 probes and analyzed (n = 4).

(E and F) The significant differential (p < 0.05) metabolite profile was analyzed by the pathway analysis of MetaboAnalyst, suggesting a strong perturbation of energy-related metabolic pathways in spermatozoa (Slc22a14 KO versus WT); increased (E), decreased (F).

(G and H) Changes of metabolites in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with WT. (G) glycolysis. (H) TCA cycle (n = 3).

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

We next conducted an untargeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based metabolomics analysis of non-capacitated WT and Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. A principal-component analysis (PCA) was performed for the 125 identified metabolites (Figure S4A), and the clear separation of the sample groups in the scores plot indicated obvious differences in WT and Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa metabolomes. The significantly up- and downregulated metabolites in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with those in the WT group (i.e., p < 0.05, Student’s t test; fold change cutoff: >1.2 or <0.8) were analyzed for pathway analysis to identify energy-related metabolic pathways that were likely altered in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. Glycolysis was upregulated in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 2E), and in contrast, the TCA cycle was downregulated (Figure 2F). The detailed intermediates involved in glycolysis and TCA cycle were illustrated in bar graphs (Figures 2G and 2H). To fertilize, spermatozoa require capacitation in the female tract or in vitro during which spermatozoa metabolism changed significantly. We then conducted metabolomic analysis of capacitated WT and Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa that showed similar metabolite alternation patterns as non-capacitated ones (Figures S4B and S4C; Table S1).

Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa have enhanced glycolysis

We next used [U-13C6]-glucose to trace label carbon in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 3A). Compared with WT spermatozoa, the Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa showed an increase in 13C incorporation throughout glycolytic metabolism (Figure 3B); this increase was accompanied by reduced levels of 13C-containing TCA intermediates in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 3C), which is highly consistent with the metabolomic data above. We further confirmed this elevation of glycolytic metabolism in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa by measuring glucose uptake (Figure 3D) and production of the end product lactate (Figure 3E), of which both were significantly increased in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the metabolic regulation of glucose in Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa

(A) Scheme outlining the path of [U-13C6]-glucose in glycolysis and the TCA cycle.

(B and C) Significantly changed spermatozoa metabolites involved in 13C-labeled metabolic flux (in glycolysis, B; the TCA cycle, C) (n = 3). m+1 means 13C-labeled compound, m+2 means two 13C-labeled compounds, and m+3 means three 13C-labeled compounds.

(D) Spermatozoa glucose uptake was measured using 2-deoxy-2-((7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino)-D-glucose (2-NBDG), a D-glucose analog, diluted in glucose-free BWW medium. Results are presented as geometric mean fluorescence intensity of live cells measured by flow cytometry (n = 4).

(E) Spermatozoa lactate production was examined using an L-lactate assay kit (n = 6).

(F) ECAR was measured using a Seahorse XF96 analyzer. Each data point represents the mean (±SEM) of three independent spermatozoa samples. A total of 10 mM glucose, 1 μM oligomycin, and 50 mM 2-DG were injected sequentially to the sample plate at the time points indicated (n = 4).

(G) ECAR values are presented as a bar graph, normalized to spermatozoa counts.

(H) OCR was measured using a Seahorse XF96 analyzer. Each data point represents the mean (±SEM) of three independent spermatozoa samples. A total of 1 μM oligomycin, 1 μM FCCP, and 4 μM antimycin with rotenone were injected sequentially to the sample plate at the time points indicated (n = 4).

(I) OCR values are presented as a bar graph, normalized to spermatozoa counts.

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

We also examined metabolic activity quantitatively by directly measuring the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR). The mean ECAR of Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa was significantly higher than that of WT spermatozoa when glucose was added, indicating elevated glycolytic activity (Figures 3F and 3G). Moreover, we found that the ECAR increase in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa was sensitive to the presence of the hexokinase inhibitor 2-G (2-Deoxyglucose), confirming that the detected increase is directly linked to glycolysis (Figures 3F and 3G). Notably, our investigations also revealed that the basal and maximal oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa were much lower than those in WT spermatozoa (Figures 3H and 3I), suggesting a disruption of energy production owing to defective mitochondrial respiration. Together, these results show that Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa reprogram their metabolism and switch from OXPHOS to glycolysis.

The lipid composition of Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa is enriched with TAG and FFA

Recalling that our KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway enrichment analysis of untargeted metabolomic data indicated downregulation of FAO in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 2F), FAO-related short-chain acyl-carnitines were significantly increased (Figure 4A), whereas long-chain acyl-carnitines were decreased in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (Figure 4B). Consistently, acyl-carnitines were significantly increased both in HEK293 Flp-in (HEK293F) cells stably overexpressing human SLC22A14 (HEK-hSLC22A14) and mouse Slc22a14 (HEK-mSlc22a14) compared with empty-vector-transfected controls (HEK-EV) (Figures S4D and 4C). This finding motivated us to carefully investigate fatty acid metabolism in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. Total lipids were extracted, and the analysis identified a total of 325 structurally diverse lipid molecules (Table S2). PCA of all detected lipids emphasized the presence of clear differences between the WT and Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa lipidomes (Figure S4E).

Figure 4.

Knockout of Slc22a14 causes lipid accumulation in spermatozoa resulting from suppressed FAO

(A) LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics analysis showing that short-chain acylcarnitine levels were significantly increased in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with WT (n = 3).

(B) LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics analysis showing that long-chain acylcarnitine levels were significantly reduced in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with WT (n = 3).

(C) LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics analysis showing that acylcarnitine levels were significantly elevated in HEK-SLC22A14 cells compared with control group. All p < 0.05 (n = 4).

(D) Bar graph illustrating the lipidome of Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa.

(E) Saturated long-chain FFA contents significantly altered in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with WT (n = 3).

(F) ATP levels of spermatozoa treated with 640 μM etomoxir, 25 mM 2-DG, and combined usage of two agents. Eto, etomoxir (n = 3).

(G) Radioactive 14CO2 measurements revealed significantly reduced FAO in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa (n = 5).

(H) Radioactive 14CO2 measurements revealed significantly increased FAO in HEK-overexpressing SLC22A14 cells compared with control group (n = 3).

(I and J) OCR in Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa. Each data point represents the mean (±SEM) of three independent samples. Where presented, 40 μM etomoxir and 1 μM oligomycin were added. The summary data are shown at the right (J) (n = 4).

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

See also Figure S4.

The levels of 99 lipids were significantly different in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with those in the WT. The differentially accumulated lipids included phospholipids (5 phosphatidylcholines [PCs], 7 phosphatidylethanolamines [PEs], 1 phosphatidylinositols [PIs], 5 phosphatidic acids [PAs], 3 phosphatidylglycerols [PGs], and 4 phosphatidylserines [PSs]), 7 cardiolipins (CLs), 1 lyso-phosphatidylinositol (LPI), 2 lyso-phosphatidic acids (LPAs), 2 ceramides (Cers), 3 sphingomyelins (SMs), 3 free fatty acids (FFAs), and 56 triglycerides (TAGs) (Table S2). Both TAG and FFA levels were significantly elevated in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa compared with those in the WT (Figures 4D, S4F, and S4G). Of particular note, among the FFAs, the FFA 16:0 and FFA 18:0 levels were significantly higher in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa than in WT (Figures 4E and S4G).

FAO is suppressed in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa

Next, to supplement our metabolomics and lipidomics-based findings, we also conducted LC-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS)-based proteomics analysis of caudal epididymal spermatozoa and identified 2,937 proteins (data not shown). Among them, fatty-acid-oxidation-related proteins such as Hadha, Hadhb, and Cpt were highly expressed although without significant differences in protein levels between WT and Slc22a14 KO mice (Figure S4H; Table S3), highlighting a contribution of FAO in spermatozoa ATP production. In vitro validation was done by treating spermatozoa with etomoxir, a known small molecule inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1). It suppressed ATP production significantly compared with untreated controls, supporting the contribution of FAO in sperm ATP production. Moreover, we observed a further reduction to nearly undetected levels upon co-treatment with etomoxir and the aforementioned hexokinase inhibitor 2-DG (Figure 4F). Together, these results indicated that FAO and glycolysis are both active for supplying ATP in spermatozoa.

To further examine the functional importance of FAO, we next used two approaches to investigate it. First, we used 14C-labeled palmitic acid (FFA 16:0) to examine overall FAO. The level of 14C-CO2, the end product of FAO, was significantly lower in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa than that in WT (Figure 4G). Accordingly, we found that overexpression of hSLC22A14 and mSlc22a14 in HEK293F cells induced significant increases of 14C-CO2 production compared with control ones (Figure 4H). Second, monitoring OCR by using CPT1 inhibitor in vitro assays showed that the extent of the etomoxir-induced OCR decrease was less pronounced in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa than that in WT (Figures 4I and 4J). Together, these results indicate that the detected Slc22a14-KO-induced reduction in ATP levels may be mediated by FAO blockade.

SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter localized at the IMM of spermatozoa

To characterize the subcellular localization of the SLC22A14 protein, we established two HEK293T cell lines transiently expressing fusion proteins, namely, EGFP-hSLC22A14 and EGFP-mSlc22a14. Immunofluorescence staining with subcellular organelle markers (Figures S5A–S5C) showed that SLC22A14 was specifically co-localized with mito-tracker red (Figure 5A). We also directly detected the presence of the SLC22A14 protein in mitochondria isolated from HEK-hSLC22A14, HEK-mSlc22a14, and HEK-EV cell lines. Briefly, we extracted total mitochondrial proteins and conducted the LC-MS/MS analysis. We identified six unique peptides for hSLC22A14 and two unique peptides for mSlc22a14 in the mitochondrial proteome (Table S4). As expected, no unique peptides for hSLC22A14 or mSlc22a14 were detected in the extracts prepared from HEK-EV cells. The representative MS/MS properties and amino acid modifications of unique peptides were illustrated in Figure 5B for hSLC22A14 and Figure 5C for mSlc22a14. We further isolated different parts from mice epididymal spermatozoa (Figures S6A and S6B), and unique peptides for Slc22a14 were identified only in mitochondria but not in the spermatozoal “head and tail” (Figure 5D; Table S4). To further confirm the endogenously expressed Slc22a14 protein in spermatozoa, by using a customized Slc22a14 antibody, we validated the KO efficiency and showed that Slc22a14 was localized to the mid-piece of sperm flagellum (mitochondrial sheath) (Figures 5E, S6C, and S6D).

Figure 5.

SLC22A14 is localized at the inner membrane of spermatozoa mitochondria

(A) SLC22A14 subcellular co-localization with mito-tracker red in HEK293T cells overexpressing the EGFP-SLC22A14 fusion protein.

(B and C) Identification of hSLC22A14 (B) and mSlc22a14 (C) in mitochondria from HEK-hSLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14 cells. The MS spectra of representative peptides are presented.

(D) Identification of mSlc22a14 in mitochondria isolated from spermatozoa. The MS characteristics of representative peptides are presented.

(E) Immunofluorescent staining of Slc22a14 in epididymal spermatozoa showed a mid-piece localization of Slc22a14. Blue, DAPI; red, Slc22a14 antibody.

(F) Super resolution confocal images of mitochondria isolated from HEK293T cells overexpressing a FLAG-SLC22A14 fusion protein. The FLAG-SLC22A14 fusion protein was labeled with an anti-FLAG-tag antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green); inner membranes were labeled with an anti-COX-IV antibody and visualized with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (red); outer membranes were labeled with an anti-TOMM20 antibody and visualized with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (blue).

(G) Plot profile of the COX-IV, FLAG-tag, and TOMM20 fluorescence intensity along the axis (line with arrow in F).

(H) Super resolution confocal images of single mitochondria in HEK293T cells. FLAG-SLC22A14 fusion protein was labeled with an anti-FLAG-tag antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green); IMM was labeled with an anti-COX-IV antibody and visualized with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (red); outer mitochondrial membranes were labeled with anti-TOMM20 antibody and visualized with a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (blue).

(I) Plot profile of the COX-IV, FLAG-tag, and TOMM20 fluorescence intensity along the axis (line with arrow in H).

See also Figures S5–S7.

We also applied structured illumination microscopy (SIM) to obtain super resolution images to more precisely define SLC22A14 localization. Specifically, we established two HEK293T cell lines stably expressing FLAG-hSLC22A14 or FLAG-mSlc22a14 fusion proteins. Immunofluorescent staining with an anti-FLAG antibody (green) based on isolated mitochondria co-localized well with the signal for the IMM marker anti-COX-IV antibody (red) (Figures 5F and S6E), and there was a clear overlap of the green and red fluorescence in the fluorescence intensity profile data (Figures 5G and S6F). Accordingly, super resolution confocal images of single mitochondria in HEK293T cells also demonstrated IMM localization of SLC22A14 (Figures 5H, 5I, S6G–S6J). These results further confirmed that SLC22A14 is localized at the spermatozoa IMM.

We next explored potential substrate(s) for SLC22A14 by performing an untargeted metabolomics analysis of mitochondria isolated from HEK-hSLC22A14, HEK-mSlc22a14, and HEK-EV cells. Notably, we identified four riboflavin-metabolism-related (riboflavin, ribitol, flavin adenine dinucleotide [FAD], and flavin mononucleotide [FMN]) metabolites among the top-ranking enriched metabolites present in HEK-SLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14 mitochondrial lysates (Figures 6A; Table S5). In contrast, the riboflavin level showed a significantly decrease in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoal mitochondria compared with the of the WT (Figure 6B). Radioactive 3H-riboflavin uptake assay in whole cells showed that overexpression of SLC22A14 induced significant increases of riboflavin content in HEK293F cells (Figure 6C). Meanwhile, overexpressing Slc22a14 increased the metabolic capacity of HEK293F cells (Figure S7A). Furthermore, we conducted homology modeling to predict the overall structures of SLC22A14 (Figures 6D and 6E), and we used 3D structural models of human and mouse SLC22A14 generated with Robetta to explore the docking of riboflavin based on the protein-ligand docking software GOLD v5.6.3 (Jones and Bubb, 2000). Also, the docking poses assessed as CHEMPLP fitness scores were 73.01 for hSLC22A14 and 66.27 for mSlc22a14 (Table S6). Isotopic uptake assays in mitochondria isolated from cells expressing hSLC22A14 or mSlc22a14 showed that SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter exhibiting high capacity but low affinity; for hSLC22A14, the Vmax for riboflavin transport was 1.185 ± 0.05614 pmol/mg protein/min and Km was 777.8 ± 107.7 nM. For mSlc22a14, the Vmax was 1.797 ± 0.07862 pmol/mg protein/min and the Km was 922.9 ± 112.9 nM (Figure 6F). To rule out the biophysical disruption of the IMM by gross overexpression, we generated mutations based on the highly conserved region and binding importance in the structural models of both hSLC22A14 and mSlc22a14 to disrupt the binding sites of riboflavin serving as a catalytically dead control (Figure S7B; Table S7). Our data showed that riboflavin levels were greatly reduced in the triple mutants from both hSLC22A14 (Y395A, R487A, and W388A) and mSlc22a14 (S394A, H275A, and S391A) compared with WT ones (Figure 6G), indicating that the uptake activity by SLC22A14 is not due to the potential IMM damage by protein overexpression.

Figure 6.

SLC22A14 is identified as a riboflavin (Rf) transporter

(A) Levels of Rf and Rf-derivative compounds in the mitochondrial metabolome of HEK-SLC22A14 cell lines (n = 3).

(B) Rf content of spermatozoal mitochondria was measured (n = 4).

(C) Uptake of radioactive Rf by HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14, and HEK-mSlc22a14 cells (n = 3).

(D and E) Homology-based 3D structural model of human SLC22A14 (D) and mouse Slc22a14 (E) based on PDB: 6H7D as the template, shown in ribbon representation. The transmembrane regions of the N domains of human (i) and mouse (iv) models are colored darker, and their respective C domains are colored lighter. Cut-through section of human SLC22A14 (ii) and mouse Slc22a14 (v) models depicted in surface representation showing the protein in an outward-occluded conformation, docked with Rf and the residues comprising the binding pocket. Close-up view of the central binding pocket showing a docked pose of Rf in the human SLC22A14 (iii) and mouse Slc22a14 (vi) model, also showing the SLC22A14 binding site for Rf.

(F) Kinetics of Rf uptake by mitochondria isolated from HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14, and HEK-mSlc22a14 cells (n = 3).

(G) Uptake of radioactive Rf by HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14, and HEK-mSlc22a14 and triple-mutated HEK-hSLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14 cells (n = 3).

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

Knockout of Slc22a14 reduces the activity of spermatozoa flavoenzymes, and riboflavin-deficient diet induces similar phenocopies in WT spermatozoa as those of Slc22a14 KO ones

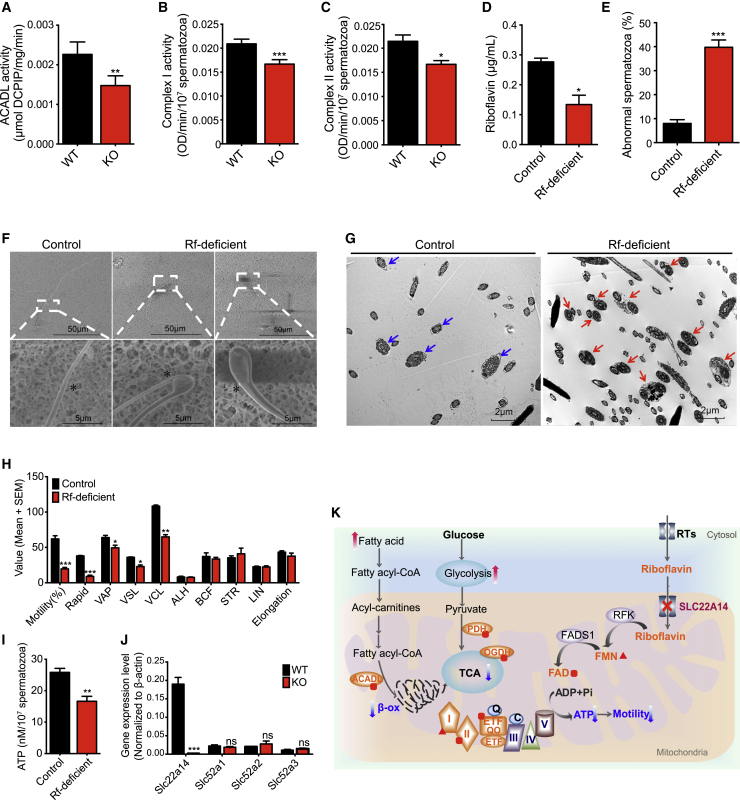

As riboflavin is well known as an essential co-factor for enzymes of both FAO and electron transfer chains (ETCs) (Barile et al., 2016), we therefore examined the activity of the long-chain FAO enzyme, long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADL), and complex I and complex II of the ETC (Figures 7A–7C). The activities of these three flavoenzymes from spermatozoa extracts were significantly decreased in Slc22a14 KO mice compared with those of the WT. Thus, beyond confirming that SLC22A14 is a high-capacity riboflavin transporter localized to the IMM, our results show that Slc22a14 KO causes reduced FAO-related flavoenzyme activity in spermatozoa.

Figure 7.

Knockout of Slc22a14 reduces the activity of spermatozoa flavoenzymes, and a Rf-deficient diet induces Slc22a14-KO-like phenotypes in WT spermatozoa

(A) Activity of ACADL in Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa (n = 4).

(B) Enzymatic activity of complex I in Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa (n = 4).

(C) Enzymatic activity of complex II in Slc22a14 KO and WT spermatozoa (n = 3).

(D) Rf levels in testis were measured using ELISA (n = 3).

(E) Spermatozoa abnormalities were categorized based on flagellum angulation (n = 4).

(F) SEM imaging of spermatozoa showing the morphology of normal spermatozoa flagellum in contrast to the angulated flagellum in Rf-deficient spermatozoa. The asterisks indicate the bending point of the spermatozoa flagellum.

(G) TEM imaging of caudal epididymis tissue showing a mature flagellum (blue arrows) of a normal spermatozoon in comparison with an Rf-deficient flagellum (red arrows).

(H) Spermatozoa motility was analyzed using the CASA system (n = 3).

(I) ATP generation from caudal epididymal spermatozoa (n = 3).

(J) Gene expression levels (mRNA) of testicular Rf transporters and Slc22a14 (n = 8).

(K) A proposed working model for SLC22A14. Rf is the precursor of FMN and FAD, which are coenzymes of many enzymes in the TCA cycle (FAD: OGDH), complex I (FMN: NADH dehydrogenase), and complex II (FAD: succinate dehydrogenase) of the ETC and in FAO (FAD: ACADL). Ablation of Slc22a14 disrupts Rf transport into the mitochondrial matrix, leading to FMN and FAD depletion and inactivity of flavoenzymes. Consequently, ATP generation from both FAO and OXPHOS are toned down, resulting in compensatory glycolysis upregulation. However, the increase of glycolysis pathway activity is insufficient to compensate for spermatozoa energy needs, resulting in spermatozoa disfunction and male infertility. Red dot, FAD; red triangle, FMN.

Student’s t test; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; error bars, SEM.

See also Figure S7.

To further confirm the role of riboflavin in spermatozoa, we treated 8-week-old male mice with riboflavin-deficient diet. After 8 weeks on this diet, we did detect reduced body weights compared with control animals with normal diet (data not shown). Although there was no obvious change in the testis weight/body weight ratio (Figure S7C), mice on the riboflavin-deficient diet had significantly reduced riboflavin content in their testis (Figure 7D) and obvious deformation in 53% of their spermatozoa flagellum (Figures 6E and S7D). Consistent with the aforementioned morphological defects we initially observed in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa, spermatozoa from the riboflavin-deficient diet group of mice exhibited similar flagellar deformation at the junction of mid-piece and principal piece (Figures 7F and 7G). Also, CASA revealed severely reduced motility and ATP generation for spermatozoa from the riboflavin-deficient diet mice (Figures 7H and 7I), which phenocopies Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. Additionally, ROS production was significantly elevated, whereas the MMP was significantly lower in riboflavin-deficient diet spermatozoa (Figures S7E and S7F). It is notable that a qPCR-based analysis of three riboflavin transporters in the Slc52 family along with Slc22a14 indicated that Slc22a14 is apparently the major transporter for riboflavin in testis (Figure 7J). Finally, these findings suggest that SLC22A14, as a spermatozoal riboflavin transporter, critically participates in energy production and fertility inside spermatozoa.

Discussion

This study sought to clarify the underlying mechanism of Slc22a14-ablation-induced male infertility. We found that SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter localized at the inner membrane of spermatozoa mitochondria. Slc22a14 ablation resulted in a pronounced spermatozoal FAO defect, which in turn caused reduced ATP production and elevated accumulation of FFAs and TAGs. Specifically, we showed that these elevations result from suppression of the activity of enzymes in FAO, the ETC, and the TCA cycle (Figure 7K). We demonstrated that SLC22A14-mediated riboflavin transport is essential for spermatozoa motility and fertility. These findings greatly enhance our understanding of energy metabolism related to both spermatozoa quality and male fertility.

Flagellar movement of the principal piece is known to be the main force-generating action propelling spermatozoa cells through viscous media, and glycolysis in the spermatozoa tail is thought to serve as the predominant energy source for spermatozoa motility in human and mice (du Plessis et al., 2015). However, growing evidence has suggested the potential importance of fatty acid metabolism in spermatozoa energy production (Ng et al., 2004; Chauvin et al., 2012; Amaral et al., 2013b). We showed that Slc22a14 null spermatozoa (with their reduced motility and ATP production) are unable to penetrate the zona pellucida to fertilize oocytes, whereas ICSI assays indicated similar fertility levels between WT and Slc22a14 KO mice; these results clearly imply that the infertility caused by Slc22a14 KO mainly results from the decreased motility of spermatozoa. Our further investigations found that the level of ATP is significantly reduced in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa, confirming that SLC22A14 somehow participates in energy metabolism in spermatozoa. Subsequently, metabolomics and confirmatory isotopic-labeling experiments showed that Slc22a14-deficient spermatozoa have significantly rewired bioenergetic pathways, with elevated glycolysis and downregulated OXPHOS. We noted that the increase of glycolysis pathway activity is insufficient to compensate for spermatozoa energy needs (i.e., inadequate to rescue ATP production and motility).

In contrast to our observations about metabolites in glycolysis, we found that numerous long-chain acyl-carnitine species are significantly decreased in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. Our analysis of the spermatozoa lipidome suggested that FFAs comprise around 25% of the total lipids (Table S2; Figure S4F); the proteomic data revealed that proteins known to be involved in FAO are highly abundant in spermatozoa, again strongly supporting that fatty acids are indeed used as an energy source by spermatozoa (Figures 4F and 4G; Table S3). Notably, a previous study reported that the accumulation of large lipid droplets inside spermatozoa induced male sterility in both humans and mice, which is related to some lipid metabolism defects (Jiang et al., 2014). Our lipidomic assay on caudal spermatozoa uncovered that both FFAs and TAGs are markedly accumulated in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa; we proposed that these elevated fatty acid levels may result from reduced FAO activity. A study has reported that spermatozoa with low motility exhibited correlations for the enrichment of saturated fatty acids (Am-in et al., 2011). We noted that although FAO accounts only for about 35% of the total ATP production in epididymal spermatozoa, it is indispensable for spermatozoa motility and fertility. Mammalian spermatozoa carry very low levels of (if any) intracellular glycogen (Buffone et al., 2012) and thus, in the absence of extracellular carbohydrate, must rely on endogenous lipids to support respiration by OXPHOS. Our work supports the idea that even though glycolysis functions as the major ATP generation pathway in spermatozoa, Slc22a14-mediated FAO through mitochondrial respiration does function in spermatozoa; thus, future studies should not underestimate this source of spermatozoa energy generation when designing experiments and/or modeling spermatozoa metabolic activity.

As several commercially available antibodies gave different cues about the localization of SLC22A14 by immunostaining (Figures S7G–S7J), we used multiple analyses based on MS, SIM, and immunostaining with customized antibody to confirm that SLC22A14 is present in the IMM of the spermatozoa mid-piece. Contrary to Maruyama et al. (2016), our results clearly indicate that SLC22A14 is a riboflavin transporter localized in the IMM, but we could not exclude other potential substrate(s) that SLC22A14 might transport considering that many transporters have multiple substrates (Nigam, 2015).

Riboflavin is the precursor of FMN and FAD, which are cofactors of many energetic enzymes in FAO, the TCA cycle, the complex I and II of the ETC (Figure 7K; Barile et al., 2016). Furthermore, as an antioxidant, riboflavin can also protect cells from oxidative damage (Saedisomeolia and Ashoori, 2018). Knockout of Slc22a14 disrupts riboflavin transport into the mitochondrial matrix, leading to FMN and FAD depletion and inhibition of the activity of a number of energetic flavoenzymes (Figure 7K). Consequently, both FAO and OXPHOS are tuned down, causing insufficient ATP generation. Moreover, we showed that both glucose and fatty acid metabolic pathways are reprogrammed in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa, resulting in enhanced glycolysis to compensate for the shortfall of ATP production. Supporting these findings in a WT genetic context, we showed that feeding WT mice a riboflavin-deficient diet induces similar spermatozoa phenocopies as in Slc22a14 KO spermatozoa. These findings together validate the functional role of riboflavin in maintaining spermatozoa quality.

Unlike somatic cells, spermatozoa undergo a maturation process that proceeds by moving along the epididymis from the caput to caudal region, and a large quantity of energy is needed to drive this process. Given potential limits in energy storage dynamics for developing sperm cells and recalling that spermatozoa carry little-to-no glycogen (Buffone et al., 2012), it is possible that the ATP generated from OXPHOS using FAO may serve as a unique metabolic process required alongside or even in place of glycolysis; that is, it seems plausible that spermatozoa may require both fatty acids and carbohydrates to concertedly power the needed motility and maturation of spermatozoa along the epididymis and toward fertilization. On the other hand, multiple-metabolite alternations caused by Slc22a14 deficiency might also result in the morphological and structural defects partially during epididymal maturation, which need to be investigated further.

Medically, our work confirms that the dysregulation of SLC22A14, a riboflavin transporter localized at the IMM in the spermatozoa mid-piece that promotes FAO energy metabolism, can cause infertility in male mice but not female mice and emphasizes that such infertility is not accompanied by disruption of hormone levels or sexual ability. As common contraceptives use modes of action based on female reproductive physiology, there is a strong bias wherein women are perceived to be solely responsible for fertility management, leaving them to face the brunt of pharmacological side effects and causing societal bias issues (Amory, 2020). The development of male contraceptives is now widely recognized as an unmet need for birth control (Matzuk et al., 2012). Our work should motivate efforts to identify male contraceptive agents, perhaps by screening for specific inhibitors against SLC22A14.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti COX-IV | Proteintech | Cat #60251-1-Ig; RRID:AB_2881372 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti TOMM20 | Abcam | Cat #Ab186735; RRID:AB_2889972 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti Calmodulin | Proteintech | Cat #10541-1-AP; RRID:AB_2069442 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti SLC22A14 | Abcam | Cat #Ab84063; RRID:AB_1861304 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti SLC22A14 | Abcam | Cat #Ab179645; |

| Rabbit Polyclonal anti Slc22a14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| Anti-Flag-tag mAb (Alexa Fluor 488) | MBL | Cat #M185-A48; RRID:AB_11126533 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (Alex Fluro 594) | Abcam | Cat #Ab150116; RRID:AB_2650601 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluro 647) | Abcam | Cat# ab150079; RRID:AB_2722623 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti sp56 | QED Bioscience | Cat #55101; N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 2-DG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat #D8375 |

| Oligomycin A | Selleck | Cat #s1478 |

| Prolong gold anti-fade reagent | Life Technologies | Cat #P10144 |

| Lyso-Tracker Red | Beyotime | Cat #C1046 |

| ER-Tracker Red | Beyotime | Cat #C1041 |

| Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos | Beyotime | Cat #C1049 |

| DAPI | Beyotime | Cat #C1005 |

| DCFH-DA | Yeasen | Cat #50101ES01 |

| 2-NBDG | Cayman | Cat #11046 |

| [U-13C6]-glucose | Cambridge isotope laboratories | Cat #CLM-1396-1 |

| [1-14C] palmitic acid | Perkin Elmer | Cat #NEC075H050UC |

| 3H-riboflavin | Moravek | Cat #2880-33-1 |

| Riboflavin-(dioxopyrimidine-13C4,15N2) | Sigma-aldrich | Cat #S705292 |

| NC(non-capacitated)-BWW medium (Biggers, Whitten, and Whittingham medium) | Genmed | Cat #GMS14001.3 |

| BWW medium | Genmed | Cat #GMS14001.1 |

| Bovine albumin (fatty acid-free) | Harveybio | Cat #HZB1156 |

| Etomoxir | Macklin | Cat #E833096 |

| Riboflavin elisa kit | Cloud-clone | Cat #CED054Ge |

| Concanavalin A | Harveybio | Cat #HZB1310-25 |

| DiL, cell plasmembrane probe | Beyotime | Cat #C1036 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Enhanced ATP Assay Kit | Beyotime | Cat #S0027 |

| XF cell mito stress test kit | Seahorse Bioscience | Cat #Cat#103015-100 |

| Total RNA purification kit | GeneMark | Cat #TR01 |

| L-lactate assay kit | Cayman | Cat #600450 |

| BCA protein assay kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat #23227 |

| Bradford assay kit | Beyotime | Cat #P0006C |

| Cell mitochondria isolation kit | Beyotime | Cat #C3601 |

| ACADL activity assay kit | Genmed | Cat #GMS50119.1.3.1 |

| Complex I activity assay kit | Cayman | Cat #700930 |

| Complex II activity assay kit | Cayman | Cat #700940 |

| JC-1 assay kit | Beyotime | Cat #C2006 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| HEK293 Flp-In | Bailong Xiao Lab | Tsinghua |

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Animal facility at Tsinghua University | N/A |

| Slc22a14 knock out mouse | This manuscript | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Genotyping primers for Slc22a14 KO mouse | This manuscript | N/A |

| Foward:CGTTCACAGGGGTGGCA CATCAG |

N/A | |

| Reverse:CTGCTCACAAAGGCTGT TCCGAA |

N/A | |

| q-PCR Primers for human SLC22A14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| Foward:TGGAGATGCTGTTACGCAGAT | N/A | |

| Reverse:CTGGAATGTGCCAAACTCCC | N/A | |

| q-PCR Primers for mouse Slc22a14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| Foward:TGGTATGTCAGTCGTGTTCCT | N/A | |

| Reverse:AGCCCCATCGCAGAGAAGT | N/A | |

| q-PCR Primers for mouse β-actin | This manuscript | N/A |

| Foward:GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | N/A | |

| Reverse:CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | N/A | |

| q-PCR Primers for human β-actin | This manuscript | N/A |

| Forward:TCATGAAGTGTGACGT GGACATC |

N/A | |

| Reverse:CAGGAGGAGCAATGAT CTTGATCT |

N/A | |

| Primers for mutated human SLC22A14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| S394A-forward:ggtttaccgtcagttacatcGC ttttacactgaacc |

N/A | |

| S394A-reverse:ggttcagtgtaaaagcgatgta actgacggtaaacc |

N/A | |

| S391A-forward:tggctgtgtgtggtttaccgtc GCTtacatcag |

N/A | |

| S391A-reverse:ctgatgtaAGCgacggt aaaccacacacagcca |

N/A | |

| H275A-forward:gccgtcatcctgcagGCCagctt cctca |

N/A | |

| H275A-reverse:tgaggaagctGGCctgcagga tgacggc |

N/A | |

| Primers for mutated mouse Slc22a14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| Y395A-forward:accgtcagttacaccGcttttac gttgagcc |

N/A | |

| Y395A-reverse:ggctcaacgtaaaagCggtgtaa ctgacggt |

N/A | |

| W388A-forward:ttggtgatgagctgtgtgGCGtttaccg tcagttacac |

N/A | |

| W388A-reverse:gtgtaactgacggt aaaCGCcacacagctcatcaccaa |

N/A | |

| R487A-forward:ttggtgctcatgctcGCAgagttcagcct | N/A | |

| R487A-reverse:aggctgaactcTGCgagcatgag caccaa |

N/A | |

| Recombinant DNA | N/A | |

| pcDNA5/FRT-hSLC22A14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| pcDNA5/FRT-mSlc22a14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| pEGFP-C1-hSLC22A14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| pEGFP-C1-mSlc22a14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| pFLAG-CMV2-hSLC22A14 | This manuscript | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Flow Jo_v10 | Flowjo | https://www.flowjo.com |

| GraphPad Prism 6 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer | Seahorse bioscience | Chicopee |

| CASA systemHamilton Thorne | IVOS II | N/A |

| Stimulated emission of depletion microscopy | LEICA | TCS SP8 gSTED 3X |

| Confocal microscope | Ziess | LSM780 |

| Transmitting electron microscope | Hitachi | H-7650 |

| Environmental scanning electron microscope | FEI | Quanta 200 FEG |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and request for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ligong Chen (ligongchen@tsinghua.edu.cn).

Materials availability

Newly generated items (mice model and antibody) are described in manuscript and listed in the Key resources table. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the corresponding author.

Data and code availability

The datasets supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository yet because all data in this study are included in this published article or Supplemental information (proteomics and lipidomics).

Experimental model and subject details

Animals

The Slc22a14 KO mice were generated and maintained on C57BL/6J background using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Cyagen Biosciences Inc., Suzhou, China). Briefly, 5′-GGGCTGACTGTGTTCCTGTC-3′ was chosen as target site to knock out nucleotides in exon 2 of Slc22a14. Injected plasmid Cas021Am-Slc22a14-gRNA-Cas9 with gRNA 5′-GGGCTGACTGTGTTCCTGTCAGG-3′(Sequences underlined are proto-spacer adjacent motif) was constructed. After in vitro transcription, Slc22a14 gRNA and cas9 mRNA were micro-injected into C57BL/6J zygotes to obtain F0 positive (−8 bp) mice identified by PCR and DNA sequencing using following primers: 5′-CGTTCACAGGGGTGGCACATCAG-3′ (Forward), 5′-CTGCTCACAAAGGCTGTTCCGAA-3′ (Reverse), fragment size of 635 bp. Mating F0 with WT mice to obtained F1 mice. F2 mice were obtained by mating heterozygous F1 litters. Heterozygous male and female mice were used for subsequent breeding and mating. Homozygous twelve-week Slc22a14 KO and WT (control group) male mice were used for experiments. Mice were housed in a temperature and light regulated room in a SPF facility and received food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed following guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Research Center of Tsinghua University. The laboratory animal facility has been licensed by the Science and Technology Commission of Beijing Municipality (SYXK-2014-0024) and accredited by Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tsinghua University.

Cell Culture and Spermatozoa Collection

HEK293T (CRL-3216) cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and HEK293F was given as a present by Prof. Bailong Xiao (Tsinghua University). All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 IU/ml penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2. Spermatozoa were removed from the caudal epididymis region by tearing the tissue into small pieces and incubated in non-capacitating BWW medium (Genmed, GMS14001.3) or other appropriate medium described in specific experiments at 37°C, 10 min for swim out. Then spermatozoa were purified by filtration with 25 μm nylon mesh and washed by PBS. The spermatozoa pellets were collected by centrifugation at 500 g, 5 min for further experiments.

Method details

Real-time PCR analysis

For q-PCR analysis of Slc22a14 mRNA level in mice and human tissues. Human cDNA samples from normal tissues were purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). Different mice tissues were removed from 8-week male mice (n = 3). Total RNA extraction using trizol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026), reverse transcription and SYBR green quantitative real-time PCR were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primers for human Slc22a14 were as follows: Forward primer: TGGAGATGCTGTTACGCAGAT; Reverse primer: CTGGAATGTGCCAAACTCCC. Primers for mouse Slc22a14 were as follows: Forward primer: TGGTATGTCAGTCGTGTTCCT; Reverse primer: AGCCCCATCGCAGAGAAGT. Gene expression level was normalized to β-actin. Primers for human β-actin were as follows: Forward primer: TCATGAAGTGTGACGTGGACATC; Reverse primer: CAGGAGGAGCAATGATCTTGATCT. Primers for mouse β-actin were as follows: Forward primer: GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG; Reverse primer: CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT.

Fertility test and in vitro fertilization

For fertility test, each Slc22a14 KO male mouse was caged with two WT females for 8 weeks to monitor the pregnancy. At the same time, vaginal plugs were checked for copulation every morning. For in vitro fertilization test, to prepare preheated TYH capacitating drop, 200 μL; HTF fertilization drop, 200 μL; egg-picking drop, 80 μL at 37°C. 12-week male mice (6 WT and 5 KO) were sacrificed and spermatozoa was released in TYH capacitating drop for 1 h. Eggs from 9-12 weeks female mice were freed into a new fertilization drop. 3-10 μL sperm droplets with high motility isolated from upstream were added into the fertilizing drop. The mixed droplets of sperm and egg were placed in cell incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 3-4 h. Fertilization was observed under microscope and the fertilized eggs were collected and cultured overnight. 2-cell embryos were observed under microscope and counted the next morning.

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

8 to 12-week C57BL/6J female mice were used as egg donors. PMSG (pregnant horse serum) was injected into female mice; At the same time, the caudal epididymis was removed from adult male mice, teared into pieces and incubated in M2 medium to release sperm. 15-20 mature eggs were added into 1 mL M2 medium (containing 5 μg/mL cytochalasin B) and incubation for 5 min. Then 10 μL sperm suspension were added to the medium above. Sperm head and tail were separated using micro injection needle, and the head was injected into the egg. After injection, the embryos were transferred to M16 medium and cultured at 37.5°C overnight. The next day, two-cell embryos were transferred into the uterus of C57BL/6J pseudo pregnant mice. After 19 days, the birth rate was assessed.

Computer Assisted Sperm Analysis

The sperm were released in PBS for 10 min under 37°C,5% CO2 for immediately analysis by CASA system. Briefly 10 μL spermatozoa suspension was add to macroslides. A CASA system (IVOS II; Hamilton Thorne, America) was carried out to analyze spermatozoa motility parameters. Sperm motility (%) was quantified, and motion parameters including VAP, average path velocity; VSL, straight-line velocity; and VCL, curvilinear velocity; ALH: amplitude of lateral head displacement; BCF: beat cross frequency; STR: straightness of cell track; LIN: linearity of cell track were measured.

Fluorescence Imaging

For spermatozoa imaging, spermatozoa were fixed using 4% PFA on slide at 4°C for 30 min, permeated by 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 min and washed in PBS. Then spermatozoa were blocked using 3% BSA and incubated with primary antibody to sp56 (QED Bioscience, 55101), Slc22a14 (Figures S7G and S7H; Abcam, Ab84063), Slc22a14 (Figures S7I and S7J; Abcam, Ab179645) or Slc22a14 (Rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated peptide of mouse Slc22a14, 40LKAIDARRDDKFASC53) (GenScript, Piscataway, USA) overnight at 4°C. After three PBS washes, spermatozoa were incubated with secondary antibody or 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), away from light. Following three PBS washes, spermatozoa were covered with prolong gold anti-fade reagent (Life Technologies, P10144). Images were obtained with a confocal microscope (LSM780; Zeiss, Italy).

For SLC22A14 subcellular localization, an EGFP-SLC22A14 fusion protein was successfully expressed in HEK293T cells. After separately incubations with 1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiL, cell plasmembrane probe, Beyotime, C1036), Lyso-Tracker Red (lysosome probe, Beyotime, C1046), ER-Tracker Red (endoplasmic reticulum probe, Beyotime, C1041), Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos (mitochondria probe, Beyotime, C1049) and DAPI (Beyotime, C1005) following manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications. Images were obtained confocal microscope (LSM780; Zeiss, Italy)

For SLC22A14 ‘sub-organelle’ localization, FLAG-SLC22A14 fusion protein was expressed in HEK293T cells. Briefly, cells were fixed in 3.7% PFA and then permeated by 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min and washed in PBS. After a blocking of 2% BSA for 1 h, cells were incubated in primary antibodies to TOMM20 (Abcam, Ab186735) and COX-IV (Proteintech, 60251-1-Ig) overnight at 4°C. After three PBS washes, cells were incubated with secondary antibody, Alex Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam, Ab150116) and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, ab150079) away from light for 1h. Following three PBS washes, cells were incubated in anti-Flag-tag mAb-Alexa Fluor 488 (MBL, M185-A48) overnight at 4°C. Following three PBS washes, cells were covered with PBS for imaging. Images were obtained using SIM (N-SIM; Nikon, Japan) and processed using NIS-Elements (Nikon, Japan) software.

Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

PAS staining was performed as previously described (Shang et al., 2017). Briefly, testis was fixed by Bouin’s fixatives (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) and embedded by paraffin. The paraffin sections were routinely dewaxed and put into periodic acid solution for 10-15 min. Then slides were stained with Schiff reagent for 10 min. After a wash with water and dehydration (50%–70%-90%-anhydrous ethanol-xylene), slices were covered with paraffin for further observation using the microscope.

Transmitting Electron Microscopy

Spermatozoa were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde with 2% PFA (pH 7.2) overnight, at 4°C. The fixed spermatozoa pellets were washed in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2-7.4) for 10 min, three times, followed by further fixation in 1.0% OsO4 (1.5% potassium hexacyanoferrate in 0.1 M PBS) in ice for 1 h. After three washes in PBS and purified water for 10 min, spermatozoa were then stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 h at room temperature away from light. Dehydration was performed by going through 30%–100% ethanol for 10 min, three times in each concentration. The dehydration was blocked by further process: incubation in 100% propylene oxide (PO) twice, 10 min; infiltration with PO: Eponate 812 2:1 for 30 min, RT, twice and eponate alone overnight. Then eponate was replaced by fresh eponate for 3 h, three times. After sample was embedded in oven at 60°C, 24 h and sliced, examination and photography were performed with a transmitting electron microscope (H-7650; Hitachi, Japan).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Spermatozoa were fixed in cold 4% PFA and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at 4°C, overnight. The fixed spermatozoa suspension was re-filtered with 25 μm nylon mesh and 0.45 μm millipore filter. The millipore filter with adherent spermatozoa were rinsed with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2-7.4) three times and further fixed in 1.0% OsO4 for 1 h at room temperature (Rodriguez and Stewart, 2007). After a thorough wash with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, graded dehydration was performed by 50%–100% ethanol for 10 min in each concentration. Then spermatozoa were rinsed twice and submerged in tert-butyl alcohol for lyophilization. Photography was performed using an environmental scanning electron microscope (Quanta 200 FEG; FEI, Netherlands) after a 60 s spurt of platinum.

ATP Determination

Spermatozoa ATP was determined using enhanced ATP assay kit (Beyotime, S0027). Briefly, fluorescein can be catalyzed to generate fluorescence by luciferase. When both fluorescein and luciferase are excessive, the production of fluorescence is proportional to the concentration of ATP within a certain concentration range of 0.1 nM to 10 μM. For ATP measurement of non-capacitated spermatozoa, spermatozoa from a pair of caudal epididymis from each mouse were released in PBS and incubated under 37°C for 10 min. Spermatozoa were filtered by 25 μm nylon mesh, then spermatozoa suspension was transferred to a new tube after a centrifugation under 4°C, 12000 rpm for 5 min and the cell precipitation was collected for ATP content determination.

For ATP measurement of spermatozoa after FAO or glycolysis inhibitor treatment, preparation of incubation solution A: XF Base medium, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 50 mM carnitine. Spermatozoa isolated from a pair of caudal epididymis were placed in different incubation solutions and incubated under 37°C for 30 min. Group1: solution A; group 2: solution A, 640 μM etomoxir; group 3: solution A with 25 mM 2-DG; group 4: solution A, 640 μM etomoxir and 25 mM 2-DG. Spermatozoa suspension was transferred to a new tube after a centrifugation at 4°C, 12000 rpm for 5 min and the cell precipitation was lysed by 200 μL ATP detection lysis solution.

For ATP measurement of HEK293T cells, HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14 cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone, SH30243.01, containing 1.0 μM) or DMEM supplemented with 5 μM riboflavin under 37°C, 5% CO2 for 6 h, then cells were washed by PBS and collected by centrifugation. The cell participation was lysed using ATP detection lysis solution. After centrifugation under 4°C, 12000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was collected for ATP content determination based on a standard ATP curve normalized to total protein or cell counts according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Flow Cytometry Measurements

For Calcein-AM/propidium iodide (Pi) double staining, spermatozoa were released in PBS containing 2 μM Calcein-AM (Beyotime, C2012) and 4 μM Pi (Beyotime, ST511) for 15 min, at 37°C in dark. Then spermatozoa were filtered with 25 μm nylon mesh and collected by centrifugation at 500 g, 5 min. Spermatozoa pellet were washed three times using PBS to remove excess dye and resuspended in PBS for detection by flow cytometry.

ROS generation was measured by incubating spermatozoa in PBS with 10 μM 2′,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Yeasen, 50101ES01) for 30 min at 37°C in dark. After centrifuged at 500 g, 3 min, spermatozoa were washed three times with PBS and analyzed using flow cytometry. 2′,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence was recorded at 525 nm following sequential excitation at 480 nm and normalized to spermatozoa counts.

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1 (Beyotime, C2006). Briefly, spermatozoa were incubated in JC-1 working solution for 20 min at 37°C in dark. After a centrifugation at 500 g and three washes using JC-1 buffer solution, spermatozoa pellets were resuspended for further analysis using flow cytometry according to manufacturer’s protocol.

For glucose uptake measurement, spermatozoa were incubated in glucose-free BWW medium containing 100 μg/ml 2-deoxy-2-((7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) amino)-D-glucose (2-NBDG; Cayman, 11046) for 30 min at 37°C in dark. Then spermatozoa were centrifuged at 500 g, 5 min and resuspended in PBS for analysis by flow cytometry. The fluorescence of 2-NBDG was recorded at 540 nm following sequential excitation at 465 nm and normalized to spermatozoa counts.

For lactate production measurement, spermatozoa were incubated in Toyoda-Yokoyama Hoshi (TYH) medium (lactate- and pyruvate- free) for 1 h, at 37°C. After spermatozoa were centrifuged at 13000 rpm, 5 min, the supernatant was measured as an indirect measurement of glycolysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman, 600450).

Assessment of Acrosome Reaction

The status of acrosome reaction was examined using Concanamycin A-FITC (Con A-FITC, Genetex, GTX01505) staining method. Con A-FITC binds specifically to glucose or mannose in spermatozoal acrosome membrane after AR induction. Briefly, Caudal epididymal spermatozoa were released in capacitating BWW medium (Genmed, GMS14001.1) for 1.5 h, at 37°C. For AR induction group, spermatozoa were treated with 1 μg/ml streptolysin O (SLO) for 5 min at room temperature, after a incubation at 4°C for 15 min, spermatozoa were transferred to 37°C for 15 min. Then capacitated spermatozoa were treated with 0.58 mM CaCl2 for 15 min to induced acrosome reaction. Following a chelation of calcium using 1 mM EDTA, AR induced and uninduced spermatozoa were collected and fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min. After washed three times with PBS, spermatozoa were stained with 5 μg/ml Con A-FITC for 10 min away from light. After washed three times with PBS, spermatozoa were stained with DAPI. Following three PBS washes, spermatozoa were covered with prolong gold anti-fade reagent. Images were obtained with a confocal microscope (LSM780; Zeiss, Italy).

[U-13C6]-glucose Labeled Glycolysis Flux Assay

Spermatozoa were released in glucose-free BWW medium containing 5.56 mM [U-13C6]-glucose (Cambridge isotope laboratories, CLM-1396-1) for 2 h, at 37°C. Then spermatozoa were filtered with 25 μm nylon mesh and collected by centrifugation at 4°C, 500 g for 5 min. Intracellular metabolites were extracted as described above. Spermatozoa were normalized to protein concentration by Bradford assay (Beyotime, P0006C).

OCR and ECAR analysis

Spermatozoa OCR and ECAR were measured using a seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse bioscience, Chicopee, MA) as previously described with some modifications (Tourmente et al., 2015) Briefly, XF96 plastic microplate was previously coated with 2 μL 0.5 mg/mL concanavalin A and dried at 37°C. Spermatozoa from caudal epididymis were released in XF base medium for 5 min at 37°C,5% CO2 and purified by filtration with 25 μm nylon mesh. The spermatozoa pellets were collected by centrifugation at 500 g, 3 min and resuspended in XF base medium and counted using a hemocytometer. Then spermatozoa were added into precoated XF96 microplate as 106 sperm per well for 2 min with equal volume of XF base medium containing no spermatozoa as black control well. After two centrifugations forward and backward of plate at 1200 g, 2 min to enhance sperm adhesion, the supernatant XF base medium was removed and replaced by assay medium. For OCR measurement, spermatozoa were covered with 175 μL assay medium (XF base medium (Seahorse, 102353), 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10 mM glucose). Port injections were performed with 1 μM oligomycin, 1 μM FCCP, 1 μM antimycin and 1 μM rotenone. For ECAR measurement, spermatozoa were covered with 175 μL assay medium (XF base medium). Port injections were performed with 10 mM glucose, 1 μM oligomycin and 50 mM 2-DG. For FAO assessment, spermatozoa were incubated in assay medium (XF base medium, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine and 50 mM carnitine). Port injections were performed with 40 μM etomoxir and 1 μM oligomycin.

Sample Preparation and Quantitative Proteomic Analysis

Spermatozoa were lysed using 8 M urea and protein concentrations were measured using the BCA method. Equal amounts of proteins from WT and Slc22a14 KO samples were separated by 1D SDS-PAGE, respectively. The gel bands of interest were excised from the gel and subsequent procedure were performed as previously described (Huo et al., 2016) with slight modification.

Spermatozoa Sample Preparation and Lipidomic Analysis

Spermatozoa pellets were collected and stocked in dry ice until lipid extraction and further mass spectrometric analysis as Lam et al. (2014) reported. Briefly, spermatozoa lipids were extracted using chloroform: methanol (1:1). The analysis was carried out using Exion UPLC-QTRAP 6500 PLUS (Sciex) liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in electrospray ionization (ESI) mode under the following conditions: curtain gas = 20, ion spray volume = 5500 V, temperature = At 400°C, ion source gas 1 = 35, ion source gas 2 = 35. Free cholesterol, sterols and esters were analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mode (APCI). Cholesteryl-2,2,3,4,4,6-d6 octadecanate and cholesterol-26,26,26,27,27,27-d6 were used as internal standards to quantify CE and Cho respectively.

Chloroform: methanol: 0.1 M ammonium acetate (100:100:4) was used as the flow equality elution to separate the lipids above on the phenomenex kinetex 2.6 μm C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm). The flow rate was 160 μL/min and the analysis time was 20 min. Based on the neutral loss MS/MS technology, d5-DAG (1,3-16:0) and d5 DAG (1,3-18:1) were used as internal standards to quantify DAG. D5-TAG (16:0)3, d5-TAG (14:0)3 and d5-TAG (18:0)3 were used as internal standards to quantify TAG.

The polar lipids were separated by NP-HPLC using phenomenex Luna 3 μm silica gel column (150 × 2.0 mm) under the following conditions: mobile phase A (chloroform: methanol: ammonium hydroxide, 89.5:10:0.5) and mobile phase B (chloroform: methanol: ammonium hydroxide: water, 55:39:0.5:5.5). Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) conversion was established for comparative analysis of polar lipids. The quantification of lipids was carried out by adding internal standards as follows: d31-16:0, d8-20:4, Cer-d18:1/17:0, GluCer-d18:1/8:0, SM-d18:1/17:0, PC-d31(16:0/18:1), DMPC, PE-d31(16:0/18:1), DMPE, PI-d31(16:0/18:1), di-C8-PI, PS-d31(16:0/18:1), DMPS, PA-d31(16:0/18:1), PA(17:0/17:0), PG-d31(16:0/18:1), DMPG, CL22:1(3)-14:1, LPC-17:0, LPI-17:1, LPE-17:1, LPA-17:0, LPS-17:1, Cholesteryl-2,2,3,4,4,6-d6 Octadeconate, Cholesterol-26,26,26,27,27,27-d6.

Radioactive FAO Measurements

Caudal epididymal spermatozoa were incubated in assay solution (XF Base medium + 2 mM glutamine + 1 mM sodium pyruvate + 50 mM carnitine + 1 μCi/mL [1-14C] palmitic acid (Perkin Elmer, NEC075H050UC) at 37°C for 4 h. At the same time, 14CO2 was collected to filter paper soaked with 0.1 M hexamethylammonium hydroxide solution. At the end of the experiment, 12% perchloric acid solution was added to end the experiment. The content of radioactive substances adsorbed on filter paper was detected using liquid scintillation counter normalized to cell counts.

Mitochondria Isolation and LC-MS/MS Analysis

Spermatozoa mitochondrial sheath isolation was performed as previously described (Hrundka, 1978) with modification and validated purity by western blot using anti-COX-IV antibody (Proteintech, 60251-1-Ig) as mitochondria marker and anti-Calmodulin (CaM) antibody (Proteintech, 10541-1-AP) as acrosome and principal piece (‘head and tail’) marker. Briefly, spermatozoa from one hundred male mice were incubated in 2 mL solution B (0.1 N HCl + 0.3 M sucrose + 60 mg/mL pepsin) for 20 min at 37°C. Following a centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 3 min, spermatozoa pellet was collected and resuspended with solution A (0.02 N HCl + 0.3 M sucrose + 30 mg/mL pepsin) at room temperature. After homogenization, 0.5 M Tris base was added to end the reaction. Supernatant was transferred to a new tube after a centrifugation at 3000 rpm and the sediment contains spermatozoa ‘head and tail’ except mitochondria. Following a centrifugation of 13000 rpm, spermatozoa ‘mid-piece’ (mitochondria) was collected as the sediment. HEK293F cell mitochondria were isolated using cell mitochondria isolation kit (Beyotime, C3601) as manufacturer’s introduction.

The protein lysates of spermatozoa ‘head and tail’, sperm ‘mid-piece’ and cell mitochondria were separated by SDS-PAGE. Gel bands of SLC22A14 proteins were excised for in-gel digestion, and proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. Briefly, proteins were disulfide reduced with 25 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide. In-gel digestion was performed using sequencing grade-modified trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37°C overnight. The peptides were extracted twice with 1% trifluoroacetic acid in 50% acetonitrile aqueous solution for 30 min. The peptide extracts were then centrifuged in a SpeedVac to reduce the volume.

For LC-MS/MS analysis, peptides were separated by a 120 min gradient elution at a flow rate 0.300 μL/min with a Thermo-Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system, which was directly interfaced with the Thermo Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer. The analytical column was a homemade fused silica capillary column (75 μm ID, 150 mm length; Upchurch, Oak Harbor, WA) packed with C-18 resin (300 A, 5 μm; Varian, Lexington, MA). Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B consisted of 100% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. The Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent acquisition mode using Xcalibur3.0 software and there is a single full-scan mass spectrum in the Orbitrap (350-1550 m/z, 120,000 resolution) followed by 3 s data-dependent MS/MS scans in an Ion Routing Multipole at 30% normalized collision energy (Higher-energy Collisional Dissociation, HCD). The MS/MS spectra from each LC-MS/MS run were searched against the selected database using Proteome Discovery searching algorithm (version 1.4).

Sample Preparation and Metabolomic Analysis

For whole spermatozoa sample, spermatozoa from a pair of caudal epididymis were released in non-capacitating BWW medium for 10 min under 37°C and collected as previously described. Then sperm pellets were resuspended in 500 uL precooled 80% MeOH/H2O (v/v),disintegrated by sonication for 4 min and 30 min on ice. After a centrifugation of 13000 rpm, 4°C, 20 min, the supernatant was transferred to a LoBind tube for vacuum evaporation. Sample dry powder were stock in −80°C fridge until further analysis. For cell mitochondria sample, SLC22A14 overexpressed mitochondria (HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14) were isolated using cell mitochondria isolation kit (Beyotime, C3601). The metabolites were extracted as described above. For spermatozoa mitochondria sample, the mitochondria sheath were isolated as previously described. Following washes of PBS and a centrifugation of 13000 rpm, spermatozoa ‘mitochondria’ was collected. Then metabolites (riboflavin) were extracted by 80% MeOH/H2O (v/v) containing 1% methane acid. The spermatozoa and mitochondria sediment were lysed in 0.1 M KOH and protein concentration were measured using BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 23227). For pathway enrichment analysis, we conducted pathway analysis on metaboanalyst website (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca) matching the Small Molecule Pathway Database (SMPDB) database.

Riboflavin Transport Assay in Cells and Mitochondria

Human SLC22A14 and mouse Slc22a14 DNA were cloned in to pcDNA5/FRT vector (Invitrogen) and transfected into HEK293F cells to establish cell lines stably overexpressing hSLC22A14 or mSlc22a14, named as HEK-hSLC22A14 and HEK-mSlc22a14 as previously described (Chen et al., 2010). And pcDNA5/FRT empty vector (EV) was transfected into HEK293F cells as control, named HEK-EV. Human SLC22A14 triple mutant recombinant plasmid was generated by QuickMutation site-directed mutagenesis Kit (Beyotime, D0206) with the primers 5′-GGTTTACCGTCAGTTACATCGCTTTTACACTGAACC-3′ (S394A

-forward), 5′-ggttcagtgtaaaagcgatgtaactgacggtaaacc-3′ (S394A-reverse), 5′-tggctgtgtgtggtttaccgtcGCTtacatcag-3′ (S391A-forward), 5′-ctgatgtaAGCgacggtaaaccacacacagcca-3′ (S391A-reverse), 5′-gccgtcatcctgcagGCCagcttcctca-3′ (H275A-forward) and 5′-tgaggaagctGGCctgcaggatgacggc-3′ (H275A-reverse) which generated triple mutations of the predicted riboflavin binding sites, named as SLC22A14-Mut. Human SLC22A14 triple mutant recombinant plasmid was generated with the primers 5′-accgtcagttacaccGcttttacgttgagcc-3′(Y395A-forward), 5′-ggctcaacgtaaaagCggtgtaactgacggt-3′(Y395A-reverse), 5′-ttggtgatgagctgtgtgGCGtttaccgtcagttacac-3′ (W388A-forward), 5′-gtgtaactgacggtaaaCGCcacacagctcatcaccaa-3′ (W388A-reverse), 5′-ttggtgctcatgctcGCAgagttcagcct-3′ (R487A-forward) and 5′-aggctgaactcTGCgagcatgagcaccaa-3′ (R487A-reverse) which generated triple mutations of the predicted riboflavin binding sites, named as SLC22A14-Mut. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

HEK-EV, HEK-hSLC22A14, HEK-mSlc22a14, HEK-hSLC22A14-Mut and HEK-mSlc22a14-Mut cells were incubated in FBS-free DMEM medium containing 0.25 μCi/mL 3H-riboflavin (Moravek, 2880-33-1) for 10 min, at 37°C. Then cells were collected by centrifugation at 13000 rpm, 5 min at 4°C. After three washes using PBS, cell radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting and normalized to cell count.