Abstract

Vaccines based on mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) pioneered by Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman at the University of Pennsylvania are a promising new vaccine platform used by two of the leading vaccines against coronavirus disease in 2019 (COVID-19). However, there are many questions regarding their mechanism of action in humans that remain unanswered. Here we consider the immunological features of LNP components and off-target effects of the mRNA, both of which could increase the risk of side effects. We suggest ways to mitigate these potential risks by harnessing dendritic cell (DC) biology.

Current Opinion in Virology 2021, 48:65–72

This review comes from a themed issue on Anti-viral strategies

Edited by Richard Plemper

For complete overview about the section, refer Engineering for Viral Resistance

Available online 24th April 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2021.03.008

1879-6257/© 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction

LNPs have grown in popularity as a delivery and adjuvant system for mRNA vaccines. An abundance of preclinical animal studies have shown the promise of this platform [1] and human clinical trials by Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech of mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines reported above 90% protection rates. The advantages of using LNPs for vaccines are numerous. In addition to being a safer alternative to viral vectors for the delivery of mRNA vaccines, LNPs are self-adjuvating and highly customizable. Furthermore, the LNP-mRNA platform can be manufactured on a large scale and adapted easily to emerging pathogens. Also, the recent development of thermostable variants [2•] will overcome the necessity of cold-chain storage, which is required to different degrees for the current mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. However, because this is a new approach for human vaccination, with different levels of reported side-effects [3•,4•,5•,6•], there remain many unknowns and caveats that should be considered.

Immunological features of LNPs

LNPs are ∼100 nm size carriers that consist of different ratios of phospholipids, cholesterol, PEGylated lipids and cationic/ionizable lipids. The LNPs’ phospholipid and cholesterol components have structural and stabilizing roles, whereas the PEGylated lipids support prolonged circulation [7•]. Cationic/ionizable lipids are included to allow complexation of the negatively charged mRNA molecules and to enable the exit of the mRNA from the endosome to the cytosol for translation [7•].

Innate immune features of LNPs

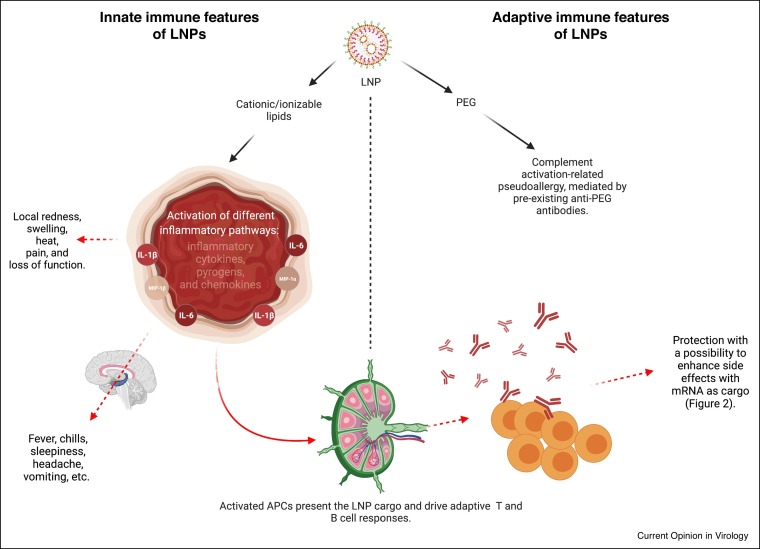

The phospholipid and cholesterol components of the LNPs also occur naturally in the mammalian cell membranes. Thus, they are unlikely to trigger any significant innate immune recognition and inflammatory responses. A less natural component of the LNPs is the cationic/ionizable lipid. Some cationic/ionizable lipids can induce inflammation by activating TLR pathways [8, 9, 10,11•] and cell toxicity [7•]. The LNPs that were widely used in preclinical vaccine studies and similar in composition to the ones used for the human SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were shown to have adjuvant effect when complexed with mRNA [12]. However, the potentially inflammatory nature of this mRNA-LNPs platform has not been assessed [1,12]. The LNP component in this platform contains proprietary ionizable lipid and supports the induction of robust humoral immune responses [12]. Humans receiving the mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines often presented with typical side effects of inflammation, such as pain, swelling, and fever [3•]. Since the mRNA of these platforms are nucleoside modified to decrease innate immune recognition and activation [13], we hypothesized that this mRNA-LNP platform’s adjuvant activity could stem from the LNPs’ inflammatory properties. Indeed, we recently reported that the LNP component of the mRNA-LNP platform used in preclinical studies is highly inflammatory [14]. Intradermal injection of these LNPs alone or in combination with non-coding poly-cytosine mRNA led to rapid and robust innate inflammatory responses, characterized by neutrophil infiltration, activation of diverse inflammatory pathways, and production of various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The same dose of LNP delivered intranasally led to similar inflammatory responses in the lung and resulted in a high mortality rate. As expected, based on previous literature [7•], the inflammatory nature of these proprietary LNPs was dependent on the ionizable lipid component. Furthermore, LNPs lacking the ionizable lipid failed to support the generation of adaptive immune responses (manuscript under review). Thus, these LNPs’ potent adjuvant activity and reported superiority comparing to other adjuvants in supporting the induction of adaptive immune responses could stem from the inflammatory nature of the ionizable lipid component. These preclinical LNPs assessed by us are similar to those used for human vaccines. Thus, the inflammatory milieu induced by the LNPs could be partially responsible for reported side effects of mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in humans, and are possibly contributory to their reported high potency for eliciting protective immunity (Figure 1 ). Whether with repeated injections, innate memory responses [15] to the ionizable lipid component of the LNPs will form and contribute to the adaptive immune responses’ and side effects' modulation remains to be determined.

Figure 1.

Immunological features of LNPs.

The cationic/ionizable lipid component of the LNP can trigger highly inflammatory responses through the activation of different innate immune sensing pathways. The resulting inflammatory milieu can support local and systemic side effects and help develop adaptive immune responses. The adaptive immune responses are dependent on the innate inflammatory environment induced by the cationic/ionizable lipids. The generated adaptive immune responses will protect from subsequent infections and might contribute to the development of side effects, as detailed in Figure 2. The PEG component of the LNP can support the development of complement activation-related pseudoallergy.

Adaptive immune features of LNPs

A growing number of reports show that polyethylene glycol (PEG) can be immunogenic, and repeat administration of PEG can induce anaphylactoid, complement activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA) reaction [16,17•,18]. Humans are likely developing PEG antibodies because of exposure to everyday products containing PEG. Therefore, some of the immediate allergic responses observed with the first shot of mRNA-LNP vaccines might be related to pre-existing PEG antibodies (Figure 1). Since these vaccines often require a booster shot, anti-PEG antibody formation is expected after the first shot. Thus, the allergic events are likely to increase upon re-vaccination.

Off-target effects of vaccine mRNA

Based on the current mRNA-LNP vaccine design, LNPs can be taken up by almost any cell type, near or far from the site of injection, transfecting them with the antigen-encoding mRNA [19]. Moreover, the mRNA used in these vaccines are nucleoside-modified to decrease inflammatory responses [13] and increase its stability in vivo, allowing extended periods of mRNA translation [20,21]. Also, a significant portion of the mRNA can be re-packaged and expelled from transfected cells in extracellular vesicles (EVs) [22••]. These vesicles could reach cells far from the injection site, further increasing the number of cells translating the antigen and extending the duration of its expression.

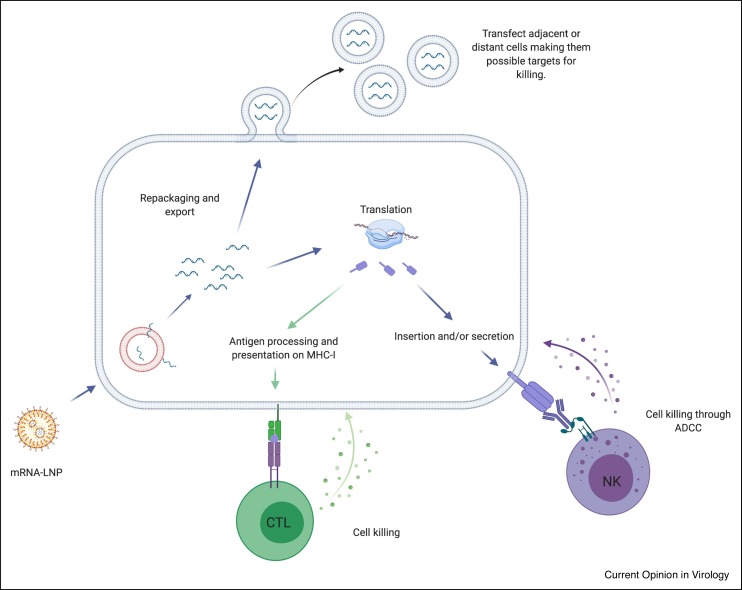

Long-term mRNA translation in non-professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) might lead to unanticipated cell killing. Similar to any other self-proteins, synthesized vaccine proteins have access to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on any nucleated cells [23]. Thus, any cell presenting antigenic determinants from the vaccine could become a target of T cell-mediated killing. The so called ‘Covid-arm’, a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, that develops in some patients several days after vaccination [24•], could be indeed an indication of effector CD8+ T cell responses targeting the cells expressing the vaccine-derived peptides. Furthermore, if vaccine-derived proteins become inserted into the plasma membrane or secreted and associated with the cell membrane, these cells could become targets of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [25]. Both CD8+ T cell-mediated killing and ADCC should become evident after an adaptive immune response has been generated and may be accentuated upon secondary immunization in the presence of memory cells and preformed antibodies (Figure 2 ). In line with this, systemic adverse events from the mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were indeed more common after the second vaccination, particularly with the highest dose [3•]. Strategies that allow delivery of the mRNA exclusively to DCs may limit the possible off-target effects. For this purpose LNPs should be conjugated to DC-targeting antibodies or ligands, such as anti-Langerin, anti-CLEC9A, anti-DEC205, mannose, and so on [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33].

Figure 2.

Possible off-target effects of the mRNA-LNP platform.

The mRNA reaching the cytosol can have different fates. They can be re-packaged in EVs that can transfect adjacent or distant cells, making them target of the immune response induced by the vaccine. The intact antigen coded by the mRNA can in theory reach the plasma membrane marking the cells for killing through ADCC. The ADCC should become evident after the antibodies specific to this antigen are formed. Since all the nucleated cells express MHC-I, the translated protein can be processed and presented, like any other self-proteins, on MHC-I to CD8 T cells. This can lead to cell killing after the effector T cells are formed. The killing should be accentuated upon booster shot when the tissue memory T cells are also present.

Considering DC biology

The success of mRNA-LNP vaccines depends not only on cellular internalization of the LNPs but on the release of mRNA from the endosomal compartment, to enable translation. It is thought that, in most cells, the ionizable lipid component becomes protonated in the progressively acidic environment of the endosome, leading to endosome destabilization and mRNA release [7•]. However, DCs have specific biology that may interfere with this process. Specifically, DCs have been reported to retain intact protein antigens for days [29,34] in mildly acidic endosomal compartments [34]. This likely allows DCs more time to display antigenic determinants to T cells and intact antigens to B cells [29,35, 36, 37]. However, the low acidity environment of the DC endo-lysosomal compartment may inhibit the endosomal escape of mRNA by failing to ionize the lipids in the LNPs. While it remains to be tested, lipid carriers that fuse with the plasma membrane and release their mRNA cargo into the cytosol might be preferred when it comes to aiding mRNA translation and subsequent antigen presentation in DCs.

Considering pre-existing inflammation

It has been shown that mRNA-LNP vaccines have an altered tissue distribution, dynamics, and uptake in animals that have been pre-exposed to inflammatory agents [7•]. These findings suggest that people with pre-existing inflammatory conditions might show altered immune responses to these vaccines and might present with more severe side-effects.

Considering vaccine delivery route

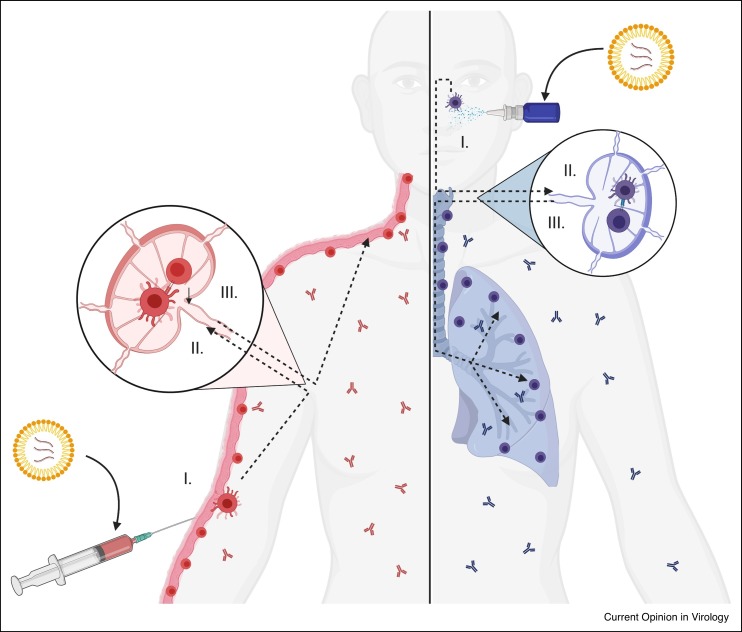

The route of vaccine delivery determines which tissue will be protected by the cellular immunity. Peripheral DCs program antigen-specific T cells in the lymphoid organs to migrate to and reside in the DC’s tissue of origin [38]. However, most current vaccines, including the mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, are delivered into the muscle. This delivery route is expected to support the formation of antibodies that provide systemic protection and T cells that patrol these organs but not the site of natural exposure and infection, the airway epithelium. The presence of virus-specific T cells in the right tissue would be highly desirable because these cells can also provide cross-protection across different strains of viruses [39, 40, 41, 42, 43]. Therefore, we would propose tailoring the vaccine’s route of administration to the pathogen’s natural route of infection and developing intranasal vaccines for respiratory viruses such as influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Route of immunization determines tissue protection by T cells.

DCs upon migration to the draining lymph nodes imprint the antigen-specific T cells to migrate and reside at their tissue of origin. Thus, vaccines administrated in the skin will imprint the T cells in the skin draining LNs to migrate to the skin and reside there as tissue-resident memory cells; while DCs, from the airway epithelia upon intranasal immunization, will instruct the T cells in the local LNs to populate the airways including the lung tissue. These cells would then confer protection at these sites upon exposure to the pathogen. The DCs will also initiate antibody responses that through lymph and bloodstream can provide systemic protection.

Broadening vaccine-induced T cell responses

Our knowledge of immune mechanisms of mRNA-LNP vaccines is still very limited. Vaccine-derived mRNAs are expected to be translated and presented by MHC class I but largely excluded from MHC class II [23]. Yet, the existing mRNA-LNP vaccination studies clearly show that both CD8+ T cell and CD4+ T cell responses are induced [1].

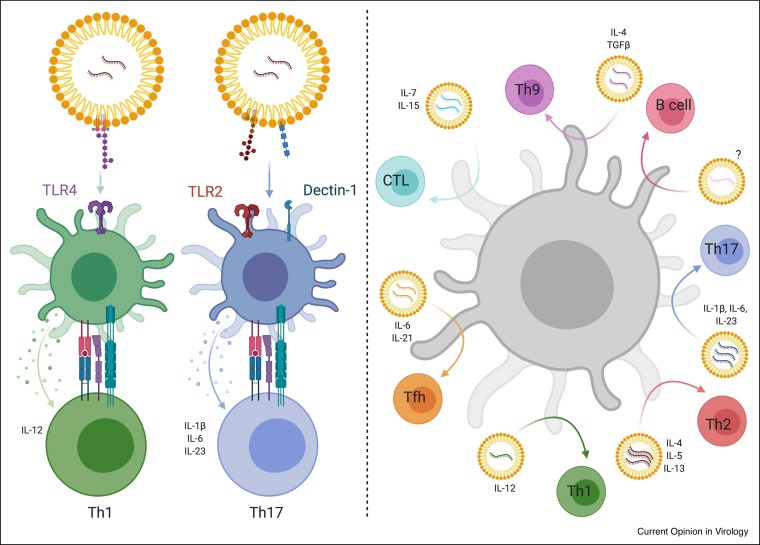

The type of Th cell response induced depends on the DC subsets and pattern-recognition receptor (PRR) pathways engaged [44]. So far, the mRNA-LNP platform has been reported to induce Th1 and T follicular helper cells, likely through the engagement of TLRs by cationic lipids [7•,11•]. To induce other Th cell subsets with the mRNA-LNP platform, we propose two strategies. First, PRR ligands could be included in the LNPs and, second, mRNAs encoding T cell-polarizing cytokines could be added to the LNPs. The first option is more restrictive as not all DC subsets express the same PRR repertoire, and thus not all DC subsets will be able to respond to the stimuli carried by the LNPs. Delivering mRNAs encoding polarizing cytokines would overcome this problem and would allow any DC subset, independent of its PRR profile, to polarize naive CD4+ T cells towards the desired lineage (Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

Strategies to exploit DC biology with the mRNA-LNP platform.

Here we present two not mutually exclusive strategies to use the mRNA-LNP platform to support a variety of different adaptive immune responses by targeting DCs. On the left panel, we present a strategy that takes into consideration that not all DC subsets express the same PRR repertoire, thus they are more functionally specialized. In this case, we can have the LNPs containing different PRR ligand(s). By changing the ligands and targeting certain DC subsets we can achieve again a variety of different adaptive responses. In this case the engagement of different PRRs will lead to secretion of distinct polarizing cytokines by the DCs. On the right panel, we propose to have mRNAs coding for certain polarizing cytokines along with the antigen (protein or mRNA coding for the antigen) delivered to all the DCs. By changing the polarizing cytokines, we could make any DC subset to support different adaptive immune responses.

Thus, with mRNA technology, there is almost no limit to modifying DC biology to match our needs.

Conclusion and future perspectives

The mRNA-LNP platform is very versatile, and as we have seen with the recent pandemic, it can provide us with a vaccine candidate in a matter of weeks. However, being a relatively new vaccine platform, as presented above, there are many unknowns and possible caveats that should be addressed before we label it safe for human use. Therefore, the discussed possible off-target effects of the mRNAs should be addressed. The LNPs can support very robust adaptive immune responses in animal models compared to other FDA-approved adjuvants. However, their higher efficacy probably relies on their highly inflammatory nature. The presentation of self-antigens in a highly inflammatory environment could lead to a break in tolerance [45]. Therefore, we believe more careful characterization of LNPs is needed to balance positive adjuvant and harmful inflammatory properties as LNP-associated vaccines move forward. Some DC subsets at optimized antigen dose can induce protective antibody responses in the absence of inflammatory agents [29,31,46]. These data suggest that LNP-based vaccine platforms that lack inflammatory cationic/ionizable lipids could be a viable option to induce protective antibody responses if targeted to specific DC subsets. The LNPs, unlike other adjuvants, can serve a dual purpose, as both delivery vehicles for different cargos and as an adjuvant. Therefore, the adjuvant properties of these LNPs should certainly be further exploited as a platform in combination with proteins, subunit vaccines, or even in combination with existing attenuated vaccines [47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52].

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease R01AI146420 to B.Z.I. Figures were generated using BioRender.

References

- 1.Alameh M.-G., Weissman D., Pardi N. 2020. RNA-Based Vaccines Against Infectious Diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2•.Zhang N.N., Li X.F., Deng Y.Q., Zhao H., Huang Y.J., Yang G., Huang W.J., Gao P., Zhou C., Zhang R.R., et al. A thermostable mRNA vaccine against COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First report on thermostable mRNA vaccine platform.

- 3•.Jackson L.A., Anderson E.J., Rouphael N.G., Roberts P.C., Makhene M., Coler R.N., McCullough M.P., Chappell J.D., Denison M.R., Stevens L.J., et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920–1931. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2022483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical trial data on mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

- 4•.Sahin U., Muik A., Derhovanessian E., Vogler I., Kranz L.M., Vormehr M., Baum A., Pascal K., Quandt J., Maurus D., et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature. 2020;586:594–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical trial data on mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

- 5•.Walsh E.E., Frenck R.W., Falsey A.R., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Neuzil K., Mulligan M.J., Bailey R., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical trial data on mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

- 6•.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., Diemert D., Spector S.A., Rouphael N., Creech C.B., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical trial data on mRNA-LNP based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

- 7•.Samaridou E., Heyes J., Lutwyche P. Lipid nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery: current perspectives. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;154–155:37–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive review on LNPs.

- 8.Lonez C., Bessodes M., Scherman D., Vandenbranden M., Escriou V., Ruysschaert J.M. Cationic lipid nanocarriers activate Toll-like receptor 2 and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways. Nanomedicine. 2014;10:775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka T., Legat A., Adam E., Steuve J., Gatot J.S., Vandenbranden M., Ulianov L., Lonez C., Ruysschaert J.M., Muraille E., et al. DiC14-amidine cationic liposomes stimulate myeloid dendritic cells through toll-like receptor 4. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1351–1357. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonez C., Vandenbranden M., Ruysschaert J.M. Cationic lipids activate intracellular signaling pathways. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Verbeke R., Lentacker I., De Smedt S.C., Dewitte H. Three decades of messenger RNA vaccine development. Nano Today. 2019;28:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2019.100766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive review on mRNA vaccines.

- 12.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Naradikian M.S., Parkhouse K., Cain D.W., Jones L., Moody M.A., Verkerke H.P., Myles A., Willis E., et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1571–1588. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karikó K., Buckstein M., Ni H., Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndeupen S., Qin Z., Jacobsen S., Estanbouli H., Bouteau A., Igyártó B.Z. The mRNA-LNP platform’s lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.04.430128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Netea M.G., Quintin J., Van Der Meer J.W.M. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a new class of drug-induced acute immune toxicity. Toxicology. 2005;216:106–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Kozma G.T., Shimizu T., Ishida T., Szebeni J. Anti-PEG antibodies: properties, formation, testing and role in adverse immune reactions to PEGylated nano-biopharmaceuticals. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;154–155:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive review on anti-PEG antibodies in driving adverse immune reactions.

- 18.Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a stress reaction in blood triggered by nanomedicines and biologicals. Mol Immunol. 2014;61:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardi N., Tuyishime S., Muramatsu H., Karikó K., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Madden T.D., Hope M.J., Weissman D. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J Control Release. 2015;217:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Welsh F.A., Ludwig J., Kato H., Akira S., Weissman D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1833–1840. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Ludwig J., Weissman D. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Maugeri M., Nawaz M., Papadimitriou A., Angerfors A., Camponeschi A., Na M., Hölttä M., Skantze P., Johansson S., Sundqvist M., et al. Linkage between endosomal escape of LNP-mRNA and loading into EVs for transport to other cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12275-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides evidence that significant amounts of mRNA can be repackaged and expelled from the cells.

- 23.Blum J.S., Wearsch P.A., Cresswell P. Pathways of antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:443–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Blumenthal K.G., Freeman E.E., Saff R.R., Robinson L.B., Wolfson A.R., Foreman R.K., Hashimoto D., Banerji A., Li L., Anvari S., et al. Delayed large local reactions to mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1273–1277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2102131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Report on delayed-type, likely T-cell–mediated hypersensitivity after vaccination with mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

- 25.Gómez Román V.R., Murray J.C., Weiner L.M. Antibody Fc: Linking Adaptive and Innate Immunity. 2013. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vangasseri D.P., Cui Z., Chen W., Hokey D.A., Falo L.D., Huang L. Immunostimulation of dendritic cells by cationic liposomes. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:385–395. doi: 10.1080/09687860600790537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulze J., Rentzsch M., Kim D., Bellmann L., Stoitzner P., Rademacher C. A liposomal platform for delivery of a protein antigen to langerin-expressing cells. Biochemistry. 2019;58:2576–2580. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R.J.E., Hogervorst T.P., Achilli S., Bruijns S.C.M., Spiekstra S., Vivès C., Thépaut M., Filippov D.V., van der Marel G.A., van Vliet S.J., et al. Targeting of the C-type lectin receptor langerin using bifunctional mannosylated antigens. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouteau A., Kervevan J., Su Q., Zurawski S.M., Contreras V., Dereuddre-Bosquet N., Le Grand R., Zurawski G., Cardinaud S., Levy Y., et al. DC subsets regulate humoral immune responses by supporting the differentiation of distinct TFH cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romani N., Thurnher M., Idoyaga J., Steinman R.M., Flacher V. Targeting of antigens to skin dendritic cells: possibilities to enhance vaccine efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:424–430. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J., Ahmet F., Sullivan L.C., Brooks A.G., Kent S.J., De Rose R., Salazar A.M., Reis e Sousa C., Shortman K., Lahoud M.H., et al. Antibodies targeting Clec9A promote strong humoral immunity without adjuvant in mice and non-human primates. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:854–864. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granot-Matok Y., Kon E., Dammes N., Mechtinger G., Peer D. Therapeutic mRNA delivery to leukocytes. J Control Release. 2019;305:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benteyn D., Heirman C., Bonehill A., Thielemans K., Breckpot K. mRNA-based dendritic cell vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;14:161–176. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.957684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutz M.B., Rovere P., Kleijmeer M.J., Rescigno M., Assmann C.U., Oorschot V.M., Geuze H.J., Trucy J., Demandolx D., Davoust J., et al. Intracellular routes and selective retention of antigens in mildly acidic cathepsin D/lysosome-associated membrane protein-1/MHC class II-positive vesicles in immature dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3707–3716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heath W.R., Kato Y., Steiner T.M., Caminschi I. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells for B cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2019;58:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Igyártó B.-Z., Magyar A., Oláh I. Origin of follicular dendritic cell in the chicken spleen. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neely H.R., Guo J., Flowers E.M., Criscitiello M.F., Flajnik M.F. “Double-duty” conventional dendritic cells in the amphibian Xenopus as the prototype for antigen presentation to B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48:430–440. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sigmundsdottir H., Butcher E.C. Environmental cues, dendritic cells and the programming of tissue-selective lymphocyte trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:981–987. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clemens E.B., Van de Sandt C., Wong S.S., Wakim L.M., Valkenburg S.A. Harnessing the power of T cells: the promising hope for a universal influenza vaccine. Vaccines. 2018;6:18. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koutsakos M., Illing P.T., Nguyen T.H.O., Mifsud N.A., Crawford J.C., Rizzetto S., Eltahla A.A., Clemens E.B., Sant S., Chua B.Y., et al. Human CD8 + T cell cross-reactivity across influenza A, B and C viruses. Nat Immunol. 2019;5:613–625. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mateus J., Grifoni A., Tarke A., Sidney J., Ramirez S.I., Dan J.M., Burger Z.C., Rawlings S.A., Smith D.M., Phillips E., et al. Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science (80-) 2020;370:89–94. doi: 10.1126/science.abd3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., Mateus J., Dan J.M., Moderbacher C.R., Rawlings S.A., Sutherland A., Premkumar L., Jadi R.S., et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181:1489–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Bert N., Tan A.T., Kunasegaran K., Tham C.Y.L., Hafezi M., Chia A., Chng M.H.Y., Lin M., Tan N., Linster M., et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature. 2020;584:457–462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2550-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janeway C.A., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charles A., Janeway J., Travers P., Walport M., Shlomchik M.J. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. edn 5. 2001. Self-tolerance and its loss. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao C., Zurawski S.M., Jarrett E.S., Chicoine B., Crabtree J., Peterson E.J., Zurawski G., Kaplan D.H., Igyártó B.Z. Skin dendritic cells induce follicular helper T cells and protective humoral immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1387–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martins S., Sarmento B., Ferreira D.C., Souto E.B. Lipid-based colloidal carriers for peptide and protein delivery - liposomes versus lipid nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2:595–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swaminathan G., Thoryk E.A., Cox K.S., Smith J.S., Wolf J.J., Gindy M.E., Casimiro D.R., Bett A.J. A tetravalent sub-unit dengue vaccine formulated with ionizable cationic lipid nanoparticle induces significant immune responses in rodents and non-human primates. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–17. doi: 10.1038/srep34215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernasconi V., Norling K., Gribonika I., Ong L.C., Burazerovic S., Parveen N., Schön K., Stensson A., Bally M., Larson G., et al. A vaccine combination of lipid nanoparticles and a cholera toxin adjuvant derivative greatly improves lung protection against influenza virus infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;14:523–536. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shirai S., Shibuya M., Kawai A., Tamiya S., Munakata L., Omata D., Suzuki R., Aoshi T., Yoshioka Y. Lipid nanoparticles potentiate CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide-based vaccine for influenza virus. Front Immunol. 2020;10:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Debin A., Kravtzoff R., Santiago J.V., Cazales L., Sperandio S., Melber K., Janowicz Z., Betbeder D., Moynier M. Intranasal immunization with recombinant antigens associated with new cationic particles induces strong mucosal as well as systemic antibody and CTL responses. Vaccine. 2002;20:2752–2763. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swaminathan G., Thoryk E.A., Cox K.S., Meschino S., Dubey S.A., Vora K.A., Celano R., Gindy M., Casimiro D.R., Bett A.J. A novel lipid nanoparticle adjuvant significantly enhances B cell and T cell responses to sub-unit vaccine antigens. Vaccine. 2016;34:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]