Abstract

This study aimed to establish a rapid in vitro plant regeneration method from rhizome buds of Kaempferia parviflora to obtain the valuable secondary metabolites with antioxidant and enzyme inhibition properties. The disinfection effect of silver oxide nanoparticles (AgO NPs) on rhizome and effects of plant growth regulators on shoot multiplication and subsequent rooting were investigated. Surface sterilization of rhizome buds with sodium hypochlorite was insufficient to control contamination. However, immersing rhizome buds in 100 mg L−1 AgO NPs for 60 min eliminated contamination without affecting the survival of explants. The number of shoots (12.2) produced per rhizome bud was higher in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 8 µM of 6-Benzyladenine (6-BA) and 0.5 µM of Thidiazuron (TDZ) than other treatments. The highest number of roots (24), with a mean root length of 7.8 cm and the maximum shoot length (9.8 cm), were obtained on medium MS with 2 µM of Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). A survival rate of 98% was attained when plantlets of K. parviflora were acclimatized in a growth room. Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was used to determine the chemical profile of K. parviflora leaf extracts. Results showed that several biologically active flavonoids reported in rhizomes were also present in leaf tissues of both in vitro cultured and ex vitro (greenhouse-grown) plantlets of K. parviflora. We found 40 and 36 compounds in in vitro cultured and ex vitro grown leaf samples, respectively. Greenhouse leaves exhibited more potent antioxidant activities than leaves from in vitro cultures. A higher acetylcholinesterase inhibitory ability was obtained for greenhouse leaves (1.07 mg/mL). However, leaves from in vitro cultures exhibited stronger butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory abilities. These results suggest that leaves of K. parviflora, as major byproducts of black ginger cultivation, could be used as valuable alternative sources for extracting bioactive compounds.

Keywords: micropropagation, silver oxide nanoparticles, flavonoids, antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibition, Kaempferia parviflora

1. Introduction

Black ginger (Kaempferia parviflora Wall. Ex Baker), a medicinal plant of the family Zingiberaceae, is native to Thailand. Black ginger rhizome is used in traditional medicine to cure colic disorder, weakness, lower blood glucose, male impotence, and ulcers [1,2,3]. It possesses antioxidant [4], anti-allergenic [5], anticancer [6], antimicrobial [1], anticholinesterase [7], anti-inflammatory [8], anti-obesity [9], and antimutagenic [10] properties. Phytochemical analysis of black ginger rhizome extracts has confirmed the presence of flavonoids [1,11], methoxyflavones [5,7,10,12,13,14], phenolic glycosides [15,16], and terpenoids [17]. Leaf extract of Kaempferia galanga has been reported to exhibit antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory [18], and sedative [19] properties. However, the biological activity and phytochemical profile of K. parviflora leaves have not been reported yet.

Multiple uses of K. parviflora have necessitated its mass collection as a raw material for pharmaceuticals purposes, leading to the depletion of this wild resource and generating pressure on K. parviflora populations [20]. Therefore, a sustainable cultivation method is needed to prevent the depletion of natural populations of K. parviflora and meet the growing demand from the pharmaceutical market. K. parviflora can be propagated using its rhizomes [20,21]. However, the availability of its rhizome is limited because of its use for extracting commercial metabolites and for preparing K. parviflora products. In addition, time (12 months) is required to obtain mature rhizomes [22]. Moreover, the yield and content of bioactive metabolites in K. parviflora are often affected by climatic change, abiotic factors, and biotic factors. In this regard, in vitro propagation technologies have been implemented for the mass propagation of various medicinal plants [22,23,24]. The establishment of efficient in vitro cell and plant regeneration techniques is essential for genetic improvement and mass production of valuable K. parviflora metabolites. In vitro production of biologically active phytochemicals through cell and organ culture as a reliable method is essential for generating cultures within a short period throughout the year.

In vitro plant regeneration [20,21], microrhizome formation [20,25], and cell suspension-based culturing [26] of K. parviflora have been reported. Axillary shoot multiplication has been achieved using terminal shoot buds [21] or rhizomatous buds [20]. The authors used 35.52 µM of 6-BA (6-Benzyladenine) to obtain maximal shoot production [20,21]. Cell suspension of K. parviflora can be established the best with liquid Murashige and Skoog [27] (MS) nutrient medium containing 1.0 mg L−1 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) [26]. However, the authors did not evaluate phytochemical compositions/contents or biological activities of the shoot, callus, or cell suspension cultures of K. parviflora [20,21,26]. Surface sterilization of plant materials obtained from wild-growing plants is essential before in vitro cultivation because bacteria and fungi grow faster in culture media than isolated explants [28]. The elimination of microorganisms attached to the surface of the rhizome is often difficult. In the meantime, the use of multiple chemicals has adverse effects on the survival of explants. Researchers have attempted to use nanoparticles (NPs) such as silver (Ag NPs), zinc (Zn NPs), and titanium dioxide (TiO2 NPs) to solve the contamination issue in plant tissue culture. However, the effectiveness of NPs on the reduction or elimination of contamination depends on their physical properties, concentrations, and exposure time [28].

The goals of this current study were (1) to establish a rapid in vitro plant regeneration method from rhizome buds of K. parviflora and (2) phytochemical analysis, antioxidant studies, and enzyme inhibition studies. The disinfection effect of AgO NPs on rhizome and effects of plant growth regulators (PGRs) on shoot multiplication and subsequent rooting were investigated. Gradient reversed-phase ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) separations with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection (in both positive and negative ion modes) were used for the identification of compounds in leaf extracts. The results showed that several biologically active flavonoids reported in rhizomes were also present in both in vitro cultured and ex vitro (greenhouse)-grown leaf tissues of plantlets of K. parviflora. Its leaf extracts also exhibited significant free radical scavenging and enzyme inhibitory abilities in in vitro assays. Therefore, the leaves of K. parviflora as major byproducts of black ginger cultivation could be used as valuable alternative sources for extracting bioactive compounds.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. In Vitro Micropropagation

2.1.1. Surface Sterilization

In vitro micropropagation is an effective and applicable method for preserving biodiversity and mass production of important plants [29,30,31]. The surface disinfection of in vivo plant materials is a prerequisite for initiating in vitro plant cultures. The initiation of sterile culture using explants obtained from underground parts is tricky because numerous microbes are attached to the surface of explants [22,28]. Previous studies have shown that surface disinfection of rhizome buds with mercuric chloride can reduce contamination in Kaempferia angustifolia [32], K. galanga [23,24], K. parviflora [22], and Kaempferia rotunda [23]. In our preliminary experiment, surface sterilization of K. parviflora rhizome buds with mercuric chloride yielded about 65% sterile culture. However, it negatively affected the organogenesis and viability of explants. Silver nitrate and antibiotics have been applied to eliminate contamination in a plant in vitro cultures [33]. Several NPs have been reported to have excellent antimicrobial activities [34]. Silver NP is comparatively free of decontaminators adverse effects, with less toxicity profile and good tissue tolerance [35]. It has been reported that Ag NPs can enter microbial cells and induce changes in intracellular structures, nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids, leading to cell death [36]. Recently, it has been shown that Ag NPs can reduce or eliminate microbial contamination in a wide range of plants, such as almond × peach rootstock [35], Araucaria excelsa [37], Capparis decidua [38], and Valeriana officinalis [39]. In this study, rhizome buds of K. parviflora were subjected to surface disinfection using AgO NPs. Rhizome buds treated with sodium hypochlorite served as controls. Decontamination and explant survival rates were significantly (p = 0.001) affected by AgO NP concentration, exposure time, and their interaction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of Ag nanoparticles (NPs) on decontamination and survival of rhizome bud explants of K. parviflora after 3 weeks of incubation.

| Ag NPs (mg L−1) | Duration (min) | Decontamination (%) | Explant Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Control) | 15.2 ± 3.3 j | 100 ± 0.0 a | |

| 25 | 30 | 23.7 ± 4.6 i | 100 ± 0.0 a |

| 50 | 44.2 ± 3.3 f | 100 ± 0.0 a | |

| 100 | 64.6 ± 4.9 c | 100 ± 0.0 a | |

| 200 | 94.9 ± 3.1 b | 73.7 ± 2.6 d | |

| 25 | 60 | 31.1 ± 4.6 h | 100 ± 0.0 a |

| 50 | 49.7 ± 3.9 e | 100 ± 0.0 a | |

| 100 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 100 ± 0.0 a | |

| 200 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 65.2 ± 3.6 f | |

| 25 | 90 | 38.1 ± 3.3 g | 91.7 ± 2.5 b |

| 50 | 56.7 ± 4.8 d | 85.2 ± 2.9 c | |

| 100 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 67.8 ± 3.1 e | |

| 200 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 44.3 ± 2.5 g | |

| Mean | 62.93 | 86.7 | |

| R-Square Coefficient of variation |

0.9896 | 0.9889 | |

| 5.34 | 2.28 | ||

| F-value | |||

| F-test | Conc | 27086.7 | 1775.4 |

| Duration | 251.4 | 1149.6 | |

| Conc * Duration | 53.4 | 89.0 | |

| p-value | |||

| Conc | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Duration | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Conc * Duration | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT).

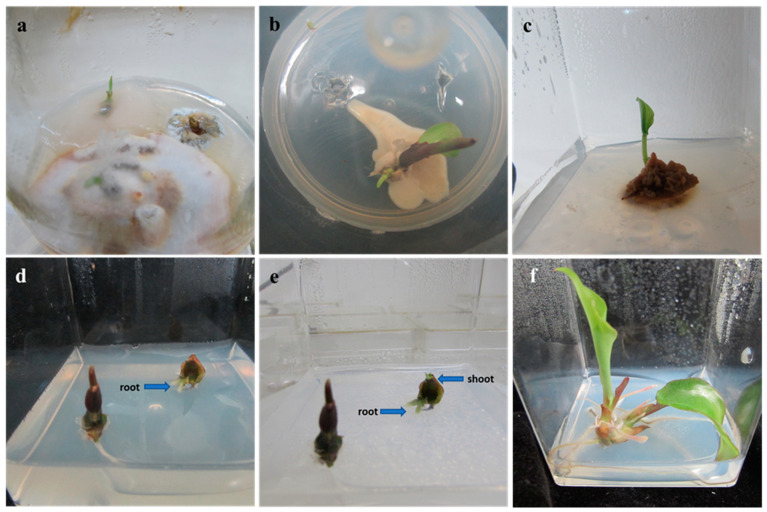

Surface sterilization of rhizome buds with sodium hypochlorite was insufficient to control the contamination (Figure 1a). However, the soaking of predisinfected rhizome buds in different AgO NPs significantly inhibited contaminants compared to the control. Treating explants with 25 mg L−1 or 50 mg L−1 AgO NPs was insufficient to control surface contaminants (Figure 1b,c). A high level of AgO NPs (200 mg L−1) harmed explants survival (Table 2). It is well known that doses of decontaminators and exposure period can affect the morphogenetic potential and survival of explants [28,38]. Increasing the concentration and duration of exposure of AgO NPs also increased the rate of decontamination. However, the reverse was observed for the survival rate of K. parviflora explants (Table 2). With increasing doses, decontamination and survival rates of explants were increased and decreased, respectively. Among the AgO NPs treatments evaluated, immersing rhizome buds for 60 min in 100 mg L−1 AgO NPs eliminated contamination without affecting the survival of explants (Table 1). Similar results have been reported for almond × peach rootstock [35], A. excelsa [37], C. decidua [38], and V. officinalis [39].

Figure 1.

Photograph showing contamination in (a) sodium hypochlorite-treated explants, (b) 25 mg L−1 AgO NPs-treated explants, and (c) 50 mg L−1 AgO NPs-treated explants. (d) Root initiation after 9 days of culture, (e) shoot induction after 17 days of culture, (f) multiple plantlets regeneration after 42 days of culture.

Table 2.

Effect of concentrations of AgO NPs and exposure time on decontamination and survival of K. parviflora rhizome bud explants.

| Factors | Decontamination (%) | Explant Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 25 mg L−1 | 30.9 d | 97.2 a |

| 50 mg L−1 | 50.2 c | 95.1 b |

| 100 mg L−1 | 88.2 b | 89.3 c |

| 200 mg L−1 | 98.3 a | 61.1 d |

| LSD | 1.82 | 1.11 |

| 30 min | 56.8 c | 93.4 a |

| 60 min | 70.2 b | 91.3 b |

| 90 min | 73.7 a | 72.3 c |

| LSD | 1.58 | 0.96 |

Means within a column, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

2.1.2. Shoot Multiplication

Rhizome buds of K. parviflora were cultured on MS nutrient medium containing 0–12 µM of cytokinin for shoot multiplication (Table 3). Roots first appeared after 9 days (Figure 1d) and shoots appeared after 17 days (Figure 1e) of cultivation. K. parviflora rhizome buds produced multiple plantlets within 42 days (Figure 1f) of cultivation. These rhizome bud explants (22.6%) produced shoots (1.2) and roots (2.3) together after 56 days on a PGR-free medium. The addition of 6-BA, 6-furfuryladenine (6-KN), or Thidiazuron (TDZ) at 1–12 µM increased the rate of regeneration, number of shoots per K. parviflora rhizome bud, and number of roots per shoot. Cytokinins are important PGRs that can promote axillary shoot multiplication [29,31,40], somatic embryogenesis [41], and adventitious shoot regeneration [42] in numerous plants. However, the application of cytokinin often adversely affects in vitro rhizogenesis [31]. In this study, simultaneous regeneration of both shoots and roots was attained using medium MS even with a high cytokinin level. Similar results have been disclosed earlier for K. galanga [43], K. parviflora [21], Hedychium coronarium [44,45], Globba marantina [46], and Hosta minor [40]. Cytokinin, concentration, and cytokinin × concentration interaction had significant effects on the regeneration rate and the number of shoots. Although cytokinin had no significant (p = 0.306) effect on the number of roots per shoot, the concentration of cytokinin (p = 0.001) and cytokinin × concentration interaction (p = 0.028) significantly affected the induction of roots (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of cytokinins on shoot multiplication from rhizome bud explants of K. parviflora after 8 weeks of incubation.

| Cytokinin | Conc (µM) | Response (%) | No. of Shoots/Explant | No. of Roots/Shoot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (MS) | 0 | 22.6 ± 2.2 k | 1.2 ± 0.4 h | 2.3 ± 0.9 gh |

| 6-BA | 1 | 34.0 ± 3.0 i | 1.4 ± 0.5 gh | 4.3 ± 1.3 b–f |

| 2 | 53.9 ± 2.7 f | 2.6 ± 0.9 efg | 5.3 ± 1.0 b | |

| 4 | 64.1 ± 2.9 c | 4.2 ± 1.6 bc | 3.6 ± 1.0 c–f | |

| 8 | 78.8 ± 3.1 a | 6.3 ± 1.6 a | 4.6 ± 1.0 bcde | |

| 12 | 70.2 ± 4.7 b | 3.1 ± 1.1 cdef | 2.9 ± 0.9 fgh | |

| 6-KN | 1 | 23.0 ± 1.8 k | 1.3 ± 0.5 h | 3.2 ± 1.2 d–f |

| 2 | 29.4 ± 2.9 j | 2.8 ± 1.2 def | 6.6 ± 1.6 a | |

| 4 | 46.6 ± 3.1 g | 3.7 ± 1.3 bcde | 4.8 ± 1.5 bc | |

| 8 | 57.7 ± 2.9 e | 2.3 ± 1.0 fgh | 3.8 ± 1.3 c–f | |

| 12 | 61.1 ± 3.7 d | 3.4 ± 1.1 cdef | 1.9 ± 0.6 h | |

| TDZ | 1 | 39.7 ± 2.7 h | 2.9 ± 0.8 def | 3.1 ± 1.5 efgh |

| 2 | 67.8 ± 2.3 b | 4.7 ± 1.3 b | 5.0 ± 1.9 bc | |

| 4 | 49.2 ± 2.8 g | 3.8 ± 1.0 bcd | 4.7 ± 2.3 bcd | |

| 8 | 53.3 ± 2.7 f | 3.0 ± 1.5 def | 3.7 ± 1.5 c–f | |

| 12 | 32.7 ± 1.6 i | 2.6 ± 0.5 efg | 2.1 ± 1.3 h | |

| Mean | 49.0 | 3.08 | 3.87 | |

| R-Square | 0.9741 | 0.5997 | 0.4839 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 5.93 | 35.68 | 35.30 | |

| F-value | ||||

| F-test | Cyto | 378.49 | 6.72 | 1.20 |

| Conc | 405.83 | 14.33 | 20.83 | |

| Cyto * Conc | 192.41 | 10.61 | 2.26 | |

| p-value | ||||

| Cyto | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.306 | |

| Conc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Cyto * Conc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.028 | |

Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

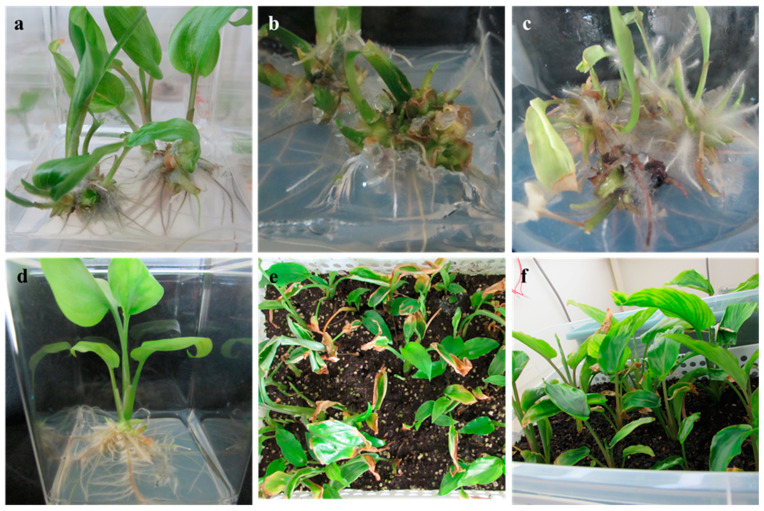

Shoot formation rate, number of shoots per rhizome bud, and number of roots per shoot varied from 34.0% to 78.8%, 1.4 to 6.3, and 2.9 to 5.3, respectively, when the medium MS was added with 1–12 µM of 6-BA. Rhizome buds of K. parviflora (78.8%) produced multiple shoots (6.3) and roots (4.6) on medium MS containing 8 µM of 6-BA (Figure 2a, Table 3). Shoots formed on medium MS added with 2 µM of 6-BA developed maximal roots (5.3). Explant response, shoot production, and root production were decreased on medium MS containing 12 µM of 6-BA. In contrast, terminal buds of K. parviflora produced a maximum of 7.16 shoots on medium MS added with 35.52 µM of 6-BA [21]. Shooting response, number of shoots per rhizome bud, and number of roots per shoot varied from 23.0% to 61.1%, 1.3 to 3.7, and 1.9 to 6.6, respectively, when the medium MS was added with 1–12 µM of 6-KN. The best shoot formation (61.1%), number of shoots (3.7), and number of roots (6.6) were noticed on medium MS added with 12 µM, 4 µM, and 2 µM of 6-KN, respectively (Table 3). The response of rhizome buds, number of shoots per rhizome bud, and number of roots per shoot varied from 32.7% to 67.8%, 2.6 to 4.7, and 2.1 to 5.0, respectively, when the medium MS was added with 1–12 µM of TDZ. The maximal response (67.8%), number of shoots (4.7), and number of roots (5.0) were noticed for medium MS added with 2 µM of TDZ (Table 3). Regeneration response, shoot production, and root production was found to be meager on medium MS added with 12 µM of TDZ. Detrimental effects of TDZ at a high dose on shoot production have also been disclosed for K. parviflora [21]. Among the cytokinins evaluated, 6-BA yielded the best explant response (60.2%), followed by TDZ (48.5%) and 6-KN (43.6%). Advantages of 6-BA on plant regeneration in vitro have been disclosed for K. parviflora [20,21] and other Zingiberaceae members such as Curcuma angustifolia [47], H. coronarium [44], and K. galanga [43]. However, a significant difference in the number of roots was not found among cytokinins (Table 4). Among all concentrations (1–12 µM) evaluated, 8 µM produced a higher shooting rate (63.3%) than other levels. However, 6-BA at a concentration of 2 µM, 4 µM, or 8 µM had a similar impact (p = 0.05) on K. parviflora shoot production (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Micropropagation of Kaempferia parviflora. (a) Rhizome buds cultivated on Murashige and Skoog (MS) nutrient medium with 8 µM 6-BA; (b) rhizome buds cultivated on MS nutrient medium with 8 µM 6-BA and 0.5 µM Thidiazuron (TDZ); (c) rhizome buds cultivated on MS nutrient medium with 8 µM 6-BA, 0.5 µM TDZ, and 1 µM Naphthalene-1-acetic acid (NAA); (d) well-developed plantlet cultivated on nutrient medium MS with 2 µM Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA); (e,f) acclimatization.

Table 4.

Effect of cytokinin types and their concentration on shoot multiplication from rhizome bud explants of K. parviflora.

| Factors | Response (%) | No. of Shoots/Explant | No. of Roots/Shoot |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-BA | 60.2 a | 3.5 a | 4.13 a |

| 6-KN | 43.6 b | 2.7 b | 4.07 a |

| TDZ | 48.5 c | 3.4 a | 3.71 a |

| LSD | 1.23 | 0.47 | 0.58 |

| 1 µM | 32.2 d | 1.9 c | 3.6 c |

| 2 µM | 50.4 c | 3.3 ab | 5.7 a |

| 4 µM | 53.3 b | 3.9 a | 4.3 b |

| 8 µM | 63.3 a | 3.9 a | 4.0 bc |

| 12 µM | 54.7 b | 3.0 b | 2.3 d |

| LSD | 1.59 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

Means within a column, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

Several works have shown that a combination of PGRs can boost the regeneration of multiple shoots for Zingiberaceae members [43,44,46,47]. Chithra et al. [43] used a combination of 11.4 µM silver nitrate, 8.8 µM 6-BA, and 2.46 µM Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) to induce maximal axillary buds (8.3) and roots (6.7) for K. galanga. Mohanty et al. [44] used a combination of 8.8 µM 6-BA and 2.7 µM NAA to obtain maximal axillary buds (3.6) and roots (4) for H. coronarium. Parida et al. [46] used a combination of 14.1 µM 6-KN and 2.7 µM Naphthalene-1-acetic acid (NAA) to induce 9.5 axillary shoots and 4.5 roots for G. marantina. Jena et al. [47] used 135.7 µM adenine sulfate, 13.3 µM 6-BA, and 5.7 µM Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) to obtain higher shoots (14.1) and roots (7.6) for C. angustifolia. In the present study, rhizome bud explants were placed on OM (optimal medium: MS plus 8 µM 6-BA) combined with other PGRs (Table 5) to produce roots and shoots within 14 days of cultivation. Supplementation of 2 µM and 4 µM of 6-KN to OM enhanced the explant response (89%) and number of shoots (9.2). Similarly, supplementation of 0.5–2 µM TDZ to OM enhanced the explant response (83.6–97.2%). The number of shoots (12.2) was higher in OM added with 0.5 µM TDZ after 56 days (Figure 2b, Table 5). The addition of 1–4 µM of NAA to OM containing 0.5 µM TDZ resulted in the maximum explant response (100%). However, shoot production was decreased (Figure 2c, Table 5). The number of roots increased as NAA level increased from 1–4 µM. Prathanturarug et al. [21] also reported that NAA and cytokinin (6-BA, TDZ) in combination cannot increase shoot regeneration for K. parviflora.

Table 5.

Effect of combinations of PGRs on shoot multiplication from rhizome bud explants of K. parviflora after 8 weeks of incubation.

| PGRs (µM) | Response (%) | No. of Shoots/Explant | No. of Roots/Shoot | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-BA | 6-KN | TDZ | NAA | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.6 ± 2.2 g | 1.2 ± 0.4 g | 2.3 ± 0.9 e |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 89.0 ± 3.7 c | 7.8 ± 1.1 cde | 5.3 ± 1.4 cd |

| 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 86.1 ± 5.2 d | 9.2 ± 1.3 b | 4.2 ± 1.0 d |

| 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 76.2 ± 2.2 f | 6.2 ± 1.4 f | 2.8 ± 0.7 e |

| 8 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 97.2 ± 1.8 b | 12.2 ± 1.8 a | 4.3 ± 1.2 d |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 90.9 ± 2.5 c | 8.1 ± 1.3 bcd | 2.7 ± 1.0 e |

| 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 83.6 ± 2.8 e | 6.4 ± 1.7 ef | 3.0 ± 1.1 e |

| 8 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 8.8 ± 1.6 bc | 6.3 ± 1.4 c |

| 8 | 0 | 0.5 | 2 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 6.8 ± 1.5 def | 8.1 ± 1.2 b |

| 8 | 0 | 0.5 | 4 | 100 ± 0.0 a | 5.9 ± 1.2 f | 9.7 ± 1.4 a |

| Mean | 84.6 | 7.3 | 4.9 | |||

| R-Square | 0.9878 | 0.8113 | 0.8255 | |||

| Coefficient of variation | 3.07 | 18.89 | 23.59 | |||

| F-value | 719.82 | 38.22 | 42.07 | |||

Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

2.1.3. Rooting and Acclimatization

Although rhizome buds of K. parviflora developed both shoots and roots on OM alone or in combination with 0.5 µM TDZ, adventitious roots failed to develop lateral roots even after 56 days of cultivation (Figure 2a,b). Several studies have shown that cytokinins have detrimental effects on lateral root induction (reviewed by Jing and Strader [48]). In general, auxin is often included in a rooting medium to induce rhizogenesis of cultured shoots. IBA is a notable auxin that can stimulate rhizogenesis of diverse plant species [29,31,40]. Therefore, shoot buds (4 weeks old) were transferred to basal medium MS added with IBA (0–12 µM) to induce and develop roots. The addition of IBA to rooting medium MS improved the rooting quality (Figure 2d). Medium MS added with 2 µM of IBA resulted in the highest number of roots (24) with a mean root length of 7.8 cm and the maximum shoot length (9.8 cm) (Table 6). Shoot buds of K. parviflora on medium MS added with 4 µM of IBA developed longer roots (8.9 cm) than those in other treatments. Plantlets of K. parviflora were acclimatized well in a growth room, having a survival rate of 98% (Figure 2e,f).

Table 6.

Effect of IBA on in vitro rooting of K. parviflora after 6 weeks of cultivation.

| IBA (µM) | Number of Roots/Shoot | Root Length (cm) | Shoot Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.9 ± 1.5 f | 4.7 ± 1.3 d | 5.8 ± 0.5 c |

| 1 | 11.0 ± 1.7 d | 5.6 ± 0.4 c | 6.1 ± 0.4 c |

| 2 | 24.0 ± 2.5 a | 7.8 ± 0.5 b | 9.8 ± 0.5 a |

| 4 | 15.8 ± 2.4 b | 8.9 ± 0.5 a | 6.6 ± 0.4 b |

| 8 | 13.2 ± 1.5 c | 5.8 ± 0.5 c | 4.4 ± 0.3 e |

| 12 | 8.9 ± 1.1 e | 3.2 ± 0.7 e | 5.3 ± 0.4 d |

| Mean | 13.29 | 5.99 | 6.3 |

| R-Square | 0.9096 | 0.8911 | 0.9499 |

| Coefficient of variation | 14.02 | 11.69 | 6.45 |

| F-Value | 96.55 | 78.53 | 182.02 |

Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

2.2. Phytochemical Compositions

Phenolic compounds are considered as leading contributors to the biological activities of plant extracts. In the present study, we determined total amounts of phenolics and flavonoids in K. parviflora extracts. Results are presented in Table 7. Leaves from the greenhouse (18.28 mg GAE/g extract) contained higher phenolics levels than leaves from in vitro cultures (14.07 mg GAE/g extract). However, levels of total flavonoids in leaves from in vitro cultures (1.55 mg RE/g extract) were higher than those from greenhouse ones (0.96 mg RE/g extract). These results indicate that in vitro culture conditions could enhance levels of flavonoids. Previously published papers have also indicated that levels of total flavonoids are changed under in vitro culture conditions [49,50,51]. Krongrawa et al. [52] reported that levels of total phenolics and flavonoids in K. parviflora are 17.88–19.07 mg GAE/g and 15.90–16.68 mg QE/g, respectively, after gamma radiation. In addition, Choi et al. [53] reported that the contents of total phenolics in different fractions of K. parviflora are 19.48–92.26 mg GAE/g extract. These different levels of total phenolics could be due to different factors, including in vitro culture conditions, extraction methods, and solvents. On the other hand, spectrophotometric measurements have some drawbacks. Most phytochemists do not use them to perform content analysis. For example, recent papers have shown that the Folin–Ciocalteu assay measures reducing power instead of total phenolics content [54]. To obtain more accurate levels of total phenolics, at least one chromatographic technique has been suggested recently [55,56,57]. In this sense, the chemical profile of K. parviflora extracts was identified by LC-MS/MS.

Table 7.

Total phenolic and flavonoid contents in the tested extracts.

| Sources of Leaves | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g) |

Total Flavonoid Content (mg RE/g) |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro cultures | 14.07 ± 0.09 | 1.55 ± 0.07 |

| The greenhouse | 18.28 ± 0.20 | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

Samples were analyzed by UHPLC to obtain chromatographic profiles of more polar portions of extracts known to mainly contain phenolic and flavonoid compounds.

All characterized compounds with their chromatographic data, MS data (retention times, protonated or deprotonated molecular ions, fragment ions), and assigned identities are shown in Table 8 and Table 9. Compounds were numbered by their elution order in a 56-day-old in vitro sample. These same numbers were used in a 90-day-old ex vitro sample. We found 40 and 36 compounds in in vitro and in vivo samples, respectively. Both samples showed a similar chromatographic profile. A wide range of compounds, mainly flavonoids, were characterized.

Table 8.

Chemical composition of the black ginger leaves from in vitro cultures.

| No. | Name | Formula | Rt | [M + H]+ | [M − H]− | Fragment 1 | Fragment 2 | Fragment 3 | Fragment 4 | Fragment 5 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 15.22 | 179.03444 | 135.0438 | 107.0492 | |||||

| 2 | Vicenin-2 (Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucoside) | C27H30O15 | 19.39 | 595.16630 | 577.1575 | 559.1442 | 457.1131 | 325.0707 | 295.0601 | ||

| 3 1 | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 19.94 | 193.05009 | 178.0261 | 149.0600 | 137.0226 | 134.0360 | 121.0278 | ||

| 4 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 1 | C26H28O14 | 20.37 | 565.15574 | 547.1459 | 511.1239 | 427.1029 | 409.0923 | 295.0602 | ||

| 5 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 2 | C26H28O14 | 20.77 | 565.15574 | 547.1455 | 511.1242 | 427.1030 | 379.0814 | 295.0602 | ||

| 6 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 3 | C26H28O14 | 21.13 | 565.15574 | 547.1458 | 511.1236 | 469.1133 | 379.0813 | 295.0602 | ||

| 7 1 | Rutin (Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside) | C27H30O16 | 23.54 | 611.16122 | 465.1043 | 303.0499 | 129.0549 | 85.0289 | 71.0497 | [15] | |

| 8 | Lumichrome | C12H10N4O2 | 24.45 | 243.08821 | 216.0769 | 200.0820 | 198.0665 | 172.0870 | 145.0761 | ||

| 9 1 | Cosmosiin (Apigenin-7-O-glucoside) | C21H20O10 | 24.50 | 433.11347 | 271.0601 | 153.0185 | 119.0493 | ||||

| 10 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (Narcissin) | C28H32O16 | 25.55 | 623.16122 | 315.0513 | 314.0432 | 299.0202 | 271.0243 | 243.0300 | [15] | |

| 11 | Tamarixetin-3-O-rutinoside | C28H32O16 | 25.74 | 623.16122 | 315.0513 | 314.0435 | 299.0198 | 271.0250 | 243.0294 | [16] | |

| 12 | Syringetin-3-O-rutinoside | C29H34O17 | 25.96 | 653.17178 | 345.0616 | 344.0539 | 329.0303 | 315.0151 | 301.0363 | [16] | |

| 13 | Acacetin-7-O-glucoside (Tilianin) | C22H22O10 | 29.06 | 447.12913 | 285.0757 | 270.0523 | 269.0444 | 242.0579 | [16] | ||

| 14 | Methoxy-trihydroxy(iso)flavanone | C16H14O6 | 30.20 | 303.08687 | 193.0499 | 167.0340 | 163.0390 | 145.0285 | |||

| 15 1 | Apigenin (4’,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O5 | 30.29 | 269.04500 | 225.0547 | 201.0548 | 151.0026 | 149.0233 | 117.0331 | ||

| 16 | Isokaempferide (3-Methoxy-4’,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) | C16H12O6 | 30.97 | 299.05556 | 284.0329 | 256.0371 | 255.0297 | 227.0342 | |||

| 17 | Undecanedioic acid | C11H20O4 | 31.36 | 215.12834 | 197.1176 | 153.1272 | 125.0955 | 57.0331 | |||

| 18 | 3,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone or 3’,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O6 | 32.44 | 343.11817 | 328.0942 | 327.0862 | 314.0793 | 313.0707 | 285.0765 | [11] | |

| 19 | Pinocembrin (5,7-Dihydroxyflavanone) | C15H12O4 | 32.77 | 255.06573 | 213.0547 | 151.0023 | 145.0645 | 107.0124 | 83.0122 | ||

| 20 | 3,3’,4’,5,7-Pentamethoxyflavone | C20H20O7 | 32.92 | 373.12873 | 358.1046 | 357.0968 | 343.0810 | 327.0863 | 312.0990 | [11] | |

| 21 | Kaempferide (4’-Methoxy-3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) | C16H12O6 | 33.09 | 299.05556 | 284.0328 | 256.0378 | 227.0340 | 151.0030 | |||

| 22 | Dihydroxy-methoxy(iso)flavone-O-acetylhexoside | C24H24O11 | 33.21 | 489.13969 | 285.0758 | 270.0522 | 269.0442 | 242.0564 | |||

| 23 | Dimethoxy-trihydroxy(iso)flavone | C17H14O7 | 33.35 | 329.06613 | 314.0434 | 299.0198 | 271.0249 | 227.0338 | |||

| 24 | Dodecanedioic acid | C12H22O4 | 33.81 | 229.14399 | 211.1334 | 167.1433 | |||||

| 25 | 5,7-Dimethoxyflavanone | C17H16O4 | 33.82 | 285.11268 | 181.0497 | 166.0261 | 138.0317 | 131.0494 | 103.0548 | [15] | |

| 26 1 | Chrysin (5,7-Dihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O4 | 33.85 | 255.06573 | 209.0595 | 153.0184 | 129.0340 | 103.0547 | 67.0185 | ||

| 27 | 5,7-Dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O4 | 34.13 | 283.09704 | 268.0729 | 267.0652 | 239.0703 | 238.0622 | 225.0538 | [11] | |

| 28 1 | Galangin (3,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O5 | 34.75 | 271.06065 | 242.0572 | 215.0701 | 165.0181 | 153.0184 | 105.0336 | ||

| 29 | 4’,5,7-Trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O5 | 34.81 | 313.10760 | 298.0837 | 297.0761 | 269.0809 | 255.0649 | 227.0711 | [11] | |

| 30 | 3,5,7-Trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O5 | 34.98 | 313.10760 | 298.0836 | 297.0758 | 280.0729 | 279.0652 | 252.0778 | [11] | |

| 31 | Dihydroxy-methoxy(iso)flavone | C16H12O5 | 35.05 | 283.06065 | 268.0375 | 267.0294 | 239.0344 | 211.0393 | |||

| 32 | Ayanin (3’,5-Dihydroxy-3,4’,7-trimethoxyflavone) | C18H16O7 | 35.20 | 345.09743 | 330.0733 | 329.0661 | 315.0499 | 287.0551 | 259.0602 | [15] | |

| 33 | 3,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone or 3’,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O6 | 35.44 | 343.11817 | 328.0940 | 327.0862 | 310.0837 | 285.0760 | 282.0886 | [11] | |

| 34 | Dihydroxy-dimethoxy(iso)flavone | C17H14O6 | 35.60 | 315.08686 | 300.0628 | 299.0548 | 272.0680 | 271.0602 | 257.0445 | ||

| 35 | Retusin (5-Hydroxy-3,3’,4’,7-tetramethoxyflavone) | C19H18O7 | 37.10 | 359.11308 | 344.0890 | 343.0812 | 329.0655 | 301.0706 | [11] | ||

| 36 | Pinostrobin (5-Hydroxy-7-methoxyflavanone) | C16H14O4 | 37.14 | 271.09704 | 229.0864 | 173.0599 | 167.0339 | 131.0494 | 103.0547 | [15] | |

| 37 | Tectochrysin (5-Hydroxy-7-methoxyflavone) | C16H12O4 | 38.08 | 269.08138 | 254.0573 | 226.0624 | 167.0338 | [11] | |||

| 38 | 4’,7-Dimethoxy-5-hydroxyflavone | C17H14O5 | 38.75 | 299.09195 | 284.0678 | 256.0728 | [11] | ||||

| 39 | 5-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O5 | 38.94 | 299.09195 | 284.0678 | 283.0601 | 256.0728 | 255.0649 | 241.0496 | [11] | |

| 40 | 5-Hydroxy-3,4’,7-trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O6 | 39.39 | 329.10252 | 314.0784 | 313.0707 | 299.0552 | 285.0756 | 271.0598 | [11] |

1 Confirmed by standard.

Table 9.

Chemical composition of the black ginger leaves from greenhouse.

| No. | Name | Formula | Rt | [M + H]+ | [M − H]− | Fragment 1 | Fragment 2 | Fragment 3 | Fragment 4 | Fragment 5 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 15.19 | 179.03444 | 135.0438 | 107.0488 | |||||

| 2 | Vicenin-2 (Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucoside) | C27H30O15 | 19.38 | 595.16630 | 577.1556 | 559.1453 | 457.1132 | 325.0707 | 295.0602 | ||

| 3 1 | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 19.95 | 193.05009 | 178.0261 | 149.0596 | 137.0231 | 134.0360 | 121.0278 | ||

| 4 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 1 | C26H28O14 | 20.43 | 565.15574 | 547.1460 | 511.1242 | 427.1027 | 409.0920 | 295.0602 | ||

| 5 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 2 | C26H28O14 | 20.78 | 565.15574 | 547.1451 | 511.1239 | 427.1030 | 379.0813 | 295.0601 | ||

| 6 | Apigenin-C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 3 | C26H28O14 | 21.14 | 565.15574 | 547.1455 | 511.1245 | 469.1141 | 379.0813 | 295.0602 | ||

| 7 1 | Rutin (Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside) | C27H30O16 | 23.53 | 611.16122 | 465.1033 | 303.0499 | 129.0549 | 85.0290 | 71.0498 | [15] | |

| 8 | Lumichrome | C12H10N4O2 | 24.46 | 243.08821 | 216.0767 | 200.0819 | 198.0662 | 172.0869 | 145.0760 | ||

| 10 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (Narcissin) | C28H32O16 | 25.55 | 623.16122 | 315.0512 | 314.0433 | 299.0203 | 271.0254 | 243.0298 | [15] | |

| 11 | Tamarixetin-3-O-rutinoside | C28H32O16 | 25.74 | 623.16122 | 315.0512 | 314.0440 | 299.0192 | 271.0250 | 243.0288 | [16] | |

| 12 | Syringetin-3-O-rutinoside | C29H34O17 | 25.97 | 653.17178 | 345.0618 | 344.0536 | 329.0306 | 315.0142 | 301.0355 | [16] | |

| 13 | Acacetin-7-O-glucoside (Tilianin) | C22H22O10 | 29.06 | 447.12913 | 285.0757 | 270.0522 | 269.0443 | 242.0567 | [16] | ||

| 15 1 | Apigenin (4’,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O5 | 30.29 | 269.04500 | 225.0555 | 201.0546 | 151.0019 | 149.0230 | 117.0330 | ||

| 41 | Dihydroxy-methoxy(iso)flavone isomer 1 | C16H12O5 | 30.85 | 283.06065 | 268.0377 | 240.0423 | 239.0346 | 211.0394 | |||

| 16 | Isokaempferide (3-Methoxy-4’,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) | C16H12O6 | 30.97 | 299.05556 | 284.0328 | 256.0379 | 255.0297 | 227.0341 | |||

| 17 | Undecanedioic acid | C11H20O4 | 31.37 | 215.12834 | 197.1175 | 153.1272 | 125.0959 | 57.0331 | |||

| 18 | 3,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone or 3’,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O6 | 32.45 | 343.11817 | 328.0943 | 327.0863 | 314.0783 | 313.0707 | 285.0760 | [11] | |

| 19 | Pinocembrin (5,7-Dihydroxyflavanone) | C15H12O4 | 32.78 | 255.06573 | 213.0556 | 151.0024 | 145.0649 | 107.0121 | 83.0123 | ||

| 20 | 3,3’,4’,5,7-Pentamethoxyflavone | C20H20O7 | 32.93 | 373.12873 | 358.1045 | 357.0966 | 343.0811 | 327.0863 | 312.0991 | [11] | |

| 22 | Dihydroxy-methoxy(iso)flavone-O-acetylhexoside | C24H24O11 | 33.20 | 489.13969 | 285.0757 | 270.0523 | 269.0440 | 242.0566 | |||

| 24 | Dodecanedioic acid | C12H22O4 | 33.81 | 229.14399 | 211.1332 | 167.1425 | |||||

| 25 | 5,7-Dimethoxyflavanone | C17H16O4 | 33.82 | 285.11268 | 181.0496 | 166.0258 | 138.0316 | 131.0493 | 103.0545 | [15] | |

| 26 1 | Chrysin (5,7-Dihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O4 | 33.85 | 255.06573 | 209.0596 | 153.0182 | 129.0341 | 103.0546 | 67.0185 | ||

| 27 | 5,7-Dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O4 | 34.14 | 283.09704 | 268.0730 | 267.0650 | 239.0702 | 238.0626 | 225.0549 | [11] | |

| 28 1 | Galangin (3,5,7-Trihydroxyflavone) | C15H10O5 | 34.76 | 271.06065 | 242.0576 | 215.0700 | 165.0183 | 153.0182 | 105.0339 | ||

| 29 | 4’,5,7-Trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O5 | 34.82 | 313.10760 | 298.0836 | 297.0761 | 269.0808 | 255.0662 | 227.0694 | [11] | |

| 30 | 3,5,7-Trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O5 | 35.00 | 313.10760 | 298.0839 | 297.0757 | 280.0730 | 279.0654 | 252.0782 | [11] | |

| 31 | Dihydroxy-methoxy(iso)flavone isomer 2 | C16H12O5 | 35.03 | 283.06065 | 268.0377 | 267.0294 | 239.0345 | 211.0394 | |||

| 32 | Ayanin (3’,5-Dihydroxy-3,4’,7-trimethoxyflavone) | C18H16O7 | 35.21 | 345.09743 | 330.0733 | 329.0653 | 315.0499 | 287.0549 | 259.0601 | [15] | |

| 33 | 3,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone or 3’,4’,5,7-Tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O6 | 35.45 | 343.11817 | 328.0944 | 327.0863 | 310.0835 | 285.0754 | 282.0886 | [11] | |

| 34 | Dihydroxy-dimethoxy(iso)flavone | C17H14O6 | 35.60 | 315.08686 | 300.0629 | 299.0552 | 272.0679 | 271.0602 | 257.0436 | ||

| 35 | Retusin (5-Hydroxy-3,3’,4’,7-tetramethoxyflavone) | C19H18O7 | 37.10 | 359.11308 | 344.0890 | 343.0815 | 329.0656 | 301.0706 | [11] | ||

| 36 | Pinostrobin (5-Hydroxy-7-methoxyflavanone) | C16H14O4 | 37.14 | 271.09704 | 229.0859 | 173.0598 | 167.0339 | 131.0494 | 103.0546 | [15] | |

| 37 | Tectochrysin (5-Hydroxy-7-methoxyflavone) | C16H12O4 | 38.09 | 269.08138 | 254.0571 | 226.0626 | 167.0342 | [11] | |||

| 39 | 5-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone | C17H14O5 | 38.94 | 299.09195 | 284.0680 | 283.0602 | 256.0729 | 255.0650 | 241.0494 | [11] | |

| 40 | 5-Hydroxy-3,4’,7-trimethoxyflavone | C18H16O6 | 39.38 | 329.10252 | 314.0784 | 313.0707 | 299.0550 | 285.0757 | 271.0602 | [11] |

1 Confirmed by standard.

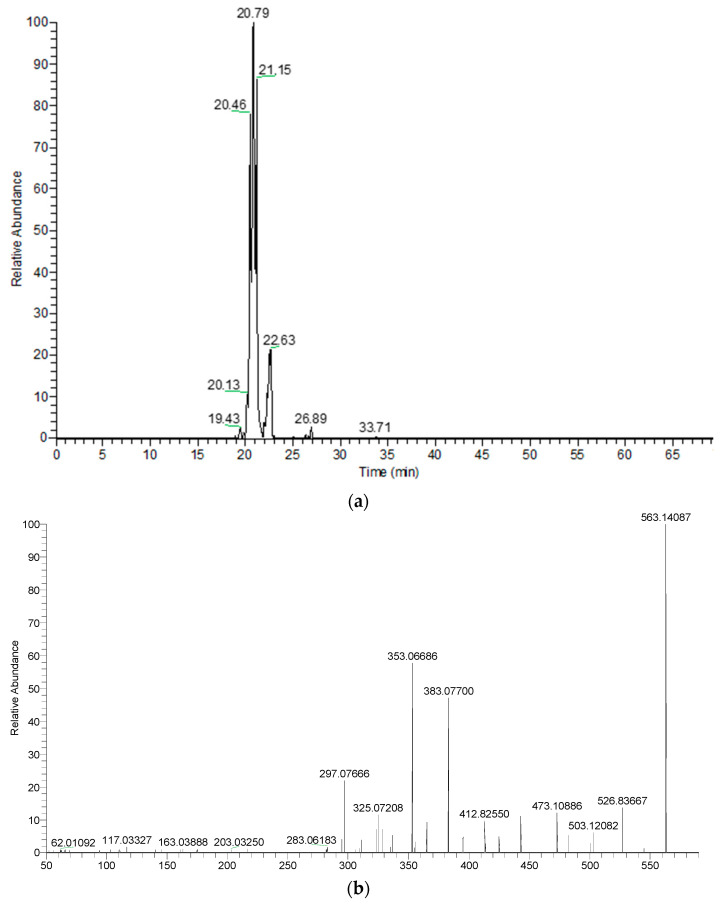

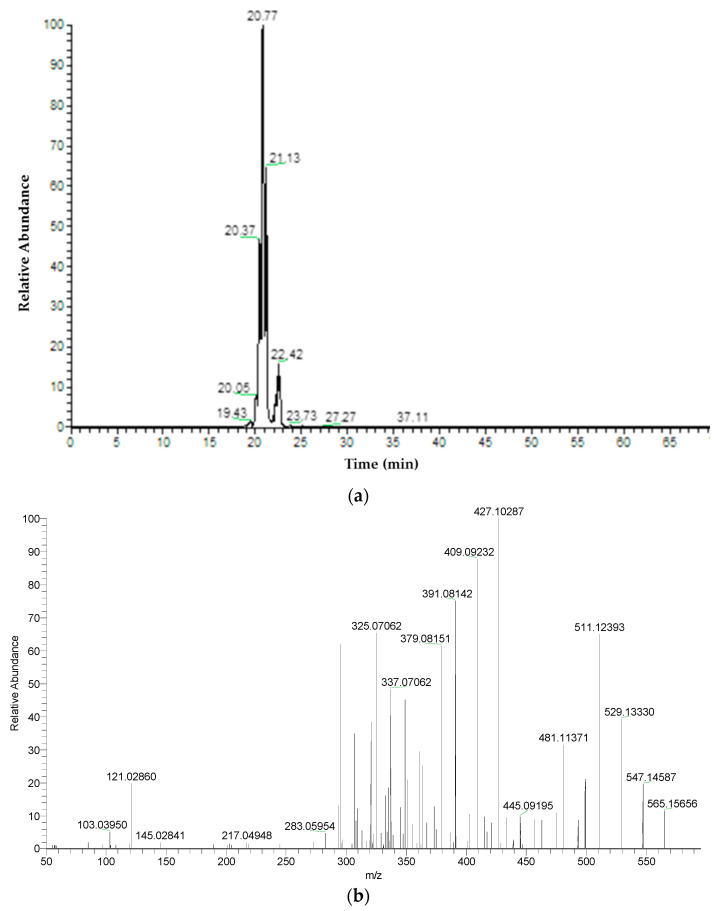

The lowest molecular mass component was caffeic acid (1) (rt: 15.19 min, MW: 180.04226). Compound 12 had the highest molecular mass. It was characterized as syringetin-3-O-rutinoside (MW: 654.17960). Compound 2 at rt: 19.38 min was confirmed as vicenin-2 (apigenin 6,8-di-C-glucoside). Characteristic fragments confirmed the substitution of two C-glucosides at positions 6 and 8 in compound 2. Compounds at rt: 20.46 min, 20.79 min, and 21.15 min were identified as apigenin C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomers (4–6) with [M − H]− at m/z 563.1409, showing ion fragments at m/z 473.1089 corresponding to [M − H-90]−, m/z 443.0974 corresponding to [M − H-120]−, m/z 383.0770 corresponding to [M − H-180]−, and m/z 353.0669 corresponding to [M − H-120-90]− in the MS/MS spectrum (Figure 3a,b). The positive ion mode was a powerful complementary tool of the negative ion mode for compounds’ structural characterization by electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS. In compound 4–6, more fragment ions were detected in the positive mode (Figure 4a,b).

Figure 3.

(a) Extracted ion chromatogram of apigenin C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomers (m/z: 563.14087) in negative ion mode (56-day-old in vitro sample). (b) MS2 spectrum of apigenin C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 1 in negative mode at a retention time of 20.52 min (56-day-old in vitro sample).

Figure 4.

(a) Extracted ion chromatogram of apigenin C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomers (m/z: 565.15574) in positive ion mode (56-day-old in vitro sample). (b) MS2 spectrum of apigenin C-hexoside-C-pentoside isomer 1 in positive mode at a retention time of 20.41 min (56-day-old in vitro sample).

2.3. Antioxidant Ability

To detect the antioxidant potential of K. parviflora in the present study, we used six assays. Antioxidant compounds are closely linked to positive effects on human health. They can minimize the negative effects of free radicals that are instable and very active. Scavenging of free radicals (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)) was tested. Results are given as IC50 values. As shown in Table 10, K. parviflora leaf extracts exhibited low DPPH scavenging abilities, with IC50 values >3 mg/mL. Regarding ABTS scavenging abilities, greenhouse leaves exhibited more potent activities than leaves from in vitro cultures. However, these tested extracts had weaker scavenging abilities compared to Trolox (IC50: 0.06 mg/mL for DPPH and 0.09 mg/mL for ABTS). Their reducing abilities were evaluated by cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. In both assays, greenhouse leaves possessed higher abilities (CUPRAC and FRAP: 2.07 mg/mL and 1.52 mg/mL, respectively). Reducing power assays reflect the electron-donating abilities of plant extracts and antioxidant compounds. Phosphomolybdenum assay is based on Mo (VI) transformation to Mo (V) by antioxidant compounds at an acidic condition. Both leaves samples had weak ability in phosphomolybdenum assays. Their IC50 values were higher than 3 mg/mL. In the last assay, the metal chelating abilities of leaf extracts were determined. Results showed that leaves from in vitro cultures had higher metal-chelating abilities, with an average IC50 value of 0.59 mg/mL. However, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was a better chelator. Several studies have reported antioxidant properties of K. parviflora extracts or fractions. For example, Krongrawa et al. [52] demonstrated antioxidant properties of K. parviflora extracts using DPPH and FRAP assays. In their study, IC50 values ranged from 129.08 µg/mL to 165.26 µg/mL in the DPPH assay. The reducing power in FRAP assay was found to be 11.96–12.48 mg ascorbic acid equivalent/g extract. Thao et al. [4] reported antioxidant abilities for peroxyl radicals and cupric reducing power of K. parviflora rhizomes. Choi et al. [53] disclosed that the ethyl acetate fraction of K. parviflora has the strongest DPPH, ABTS, and ferric reducing power. As can be seen in earlier papers, few reports are available on the antioxidant properties of K. parviflora. Thus, the results of the present study provide valuable scientific knowledge of K. parviflora.

Table 10.

Antioxidant properties of the tested samples (IC50 (mg /mL)).

| Sources of Leaves and Standards | DPPH | ABTS | CUPRAC | FRAP | PBD | Chelating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro cultures | >3 b | 2.99 ± 0.20 c | 2.82 ± 0.03 c | 1.94 ± 0.01 c | >3 b | 0.59 ± 0.01 b |

| The greenhouse | >3 b | 2.20 ± 0.05 b | 2.07 ± 0.01 b | 1.52 ± 0.02 b | >3 b | 0.70 ± 0.09 c |

| Trolox | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.52 ± 0.02 a | nt |

| EDTA | nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | 0.02 ± 0.001 a |

nt: Not tested. PBD: Phosphomolybdenum. Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

2.4. Enzyme Inhibitory Effects

Although the world is a healthier place today, humanity still faces global health problems. Several infectious diseases, including polio, Ebola, and smallpox, have been eliminated by some effective treatment strategies over the centuries. However, the prevalence of some noncommunicable diseases is almost epidemic all over the world. For example, about 500 million people are affected by diabetes mellitus [58]. In this sense, we need effective therapeutic tools to overcome the burden. Many studies have demonstrated that enzymes are effective drug targets [59]. According to this approach, inhibition of some clinical enzymes is linked to the alleviated symptoms observed. For example, inhibition of amylase and glucosidase as main hydrolyzing enzymes of carbohydrates can control blood glucose levels after a carbohydrate-rich diet [60]. Thus, enzyme inhibitors are among the most common topics in medical and pharmaceutical areas. Researchers have attempted to use several chemicals for this purpose. However, these chemicals have produced unpleasant effects, including toxicity and gastrointestinal disturbances [61,62]. Taken together, these findings suggest that we need to replace synthetics with safe and effective ones from natural resources.

In the current paper, we tested the enzyme inhibiting properties of K. parviflora leaves. Results are given as IC50 values (Table 11). The best AChE inhibitory ability was obtained for leaves from greenhouse-grown K. parviflora (1.07 mg/mL). However, leaves from in vitro cultures exhibited stronger BChE inhibitory abilities than leaves from the greenhouse. Regarding tyrosinase inhibitory activity, both leaves had some potential, with an average IC50 value of 0.71 mg/mL. Finally, the best amylase inhibition ability was obtained for leaves from the greenhouse, with an IC50 value of 1.37 mg/mL. However, inhibitor standards were more active than tested extracts in all assays performed. Observed enzyme inhibitory abilities might be explained by the presence of some compounds in these leaf extracts. For example, some phenolic acids such as caffeic [63,64,65] and ferulic acids [66,67,68] have been shown to possess significant inhibitor properties in earlier studies. Again, flavonoids including rutin [69,70] and quercetin [69,71] have been reported as effective enzyme inhibitors. Thus, K. parviflora leaves could be useful as sources of natural enzyme inhibitors for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications.

Table 11.

Enzyme inhibitory properties of tested samples (IC50 (mg /mL)).

| Sources of Leaves and Standards | AChE | BChE | Tyrosinase | Amylase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro cultures | 1.15 ± 0.04 b | 0.95 ± 0.10 c | 0.71 ± 0.01 b | 1.41 ± 0.01 b |

| The greenhouse | 1.07 ± 0.10 b | 1.67 ± 0.11 b | 0.71 ± 0.01 b | 1.37 ± 0.05 b |

| Galantamine | 0.003 ± 0.001 a | 0.007 ± 0.002 a | nt | nt |

| Kojic acid | nt | nt | 0.08 ± 0.001 a | nt |

| Acarbose | nt | nt | nt | 0.68 ± 0.01 a |

nt: Not tested. Means ± SDs, followed by the same letters within a column, were not significantly different p < 0.05 by DMRT.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. In Vitro Micropropagation

3.1.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Oxide Nanoparticles (AgO NPs)

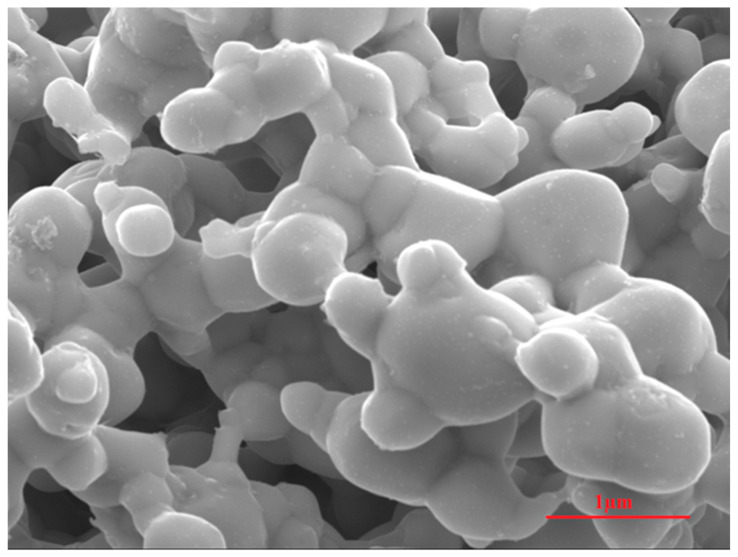

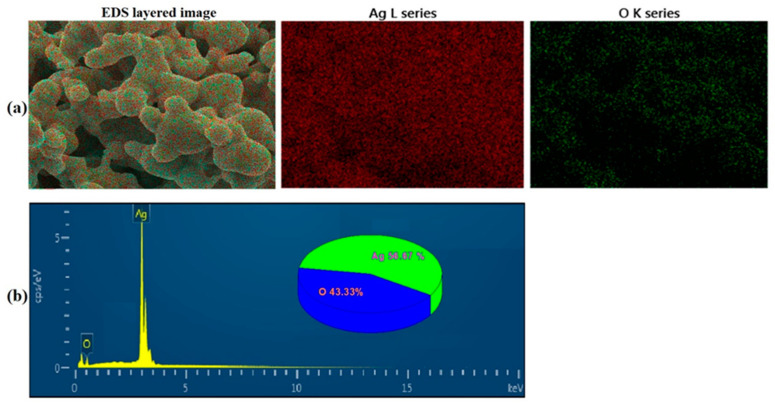

Silver oxide nanoparticles were synthesized with the hydrothermal method using polyethylene glycol and silver nitrates purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For the synthesis of AgO nanoparticles, 25 g of polyethylene glycol (PEG) was dissolved in 1 L of deionized (DI) water and stirred unceasingly for 1 h at 60 °C. After complete dissolution as a homogeneous solution, 1 g of silver nitrate salt was added into the aqueous PEG solution under constant stirring for another 1 h. After a set period, formed AgO nanoparticles were filtered using a membrane filter (0.2 μm, Millipore). These filtered particles were washed several times with DI water. After washing with ethanol, they were then dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight [72]. These dried AgO nanoparticles were characterized by a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) attached with an energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDAX) setup to determine their morphological and composition properties. A Hitachi Ultrahigh Resolution SEM (S-4800) attached with an EDAX module was used for morphological and compositional characterization of silver oxide nanoparticles. For SEM characterization, synthesized particles were spread onto adhesive conductive carbon tapes. The platinum metal was then used to coat these particles.

SEM images of hydrothermally synthesized silver oxide nanoparticles are presented in Figure 5, showing that these AgO particles were spherical in shape with different sizes due to the highly agglomerated nano-crystallite gains of AgO. The surface of these agglomerated particles clearly showed nanocrystalline grains, confirming the nano-nature of the synthesized AgO. The compositions of these synthesized AgO particles are presented in Figure 6, showing the EDX mapping (Figure 6a) and EDX spectrum (Figure 2b) of the product. EDX mapping displayed a uniform distribution for both Ag and O elements. The composition levels are shown in Figure 6b. The results confirmed a stoichiometric formation of AgO nanoparticles through hydrothermal synthesis.

Figure 5.

Field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) image of synthesized AgO nanoparticles.

Figure 6.

(a) Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping and (b) spectrum of AgO nanoparticles.

3.1.2. Plant Materials and Surface Decontamination

Rhizomes of K. parviflora harvested from field-grown plants were cleaned under running tap water, planted in plastic trays containing a mixture of autoclaved perlite/peat moss (1:1, v/v), and kept in a growth room in darkness at 24 ± 1 °C. After 3 weeks, rhizome developing buds were isolated, soaked in detergent solution (0.01%, v/v) for 5 min, and then thoroughly washed under tap water for 45 min. These rhizome buds were sterilized in sodium hypochlorite (2.5% v/v) for 12 min and rinsed several times with sterilized distilled water. These rhizome buds were again immersed in 0–200 mg L−1 AgO NPs suspension for 30 min, 60 min, or 90 min and rinsed 6 times with sterilized distilled water. These buds were excised from sterilized rhizomes and placed on MS nutrient medium containing 2.0 µM Thidiazuron (TDZ), 3% sucrose, and 0.8% plant agar (pH 5.6–5.8). Cultures were kept at 24 ± 1 °C for 21 days with a 16h/8h light/dark photoperiod (40–45 µmol m−2 s−1) provided by cool white fluorescent tubes. Experiments were conducted with as a completely randomized design (CRD). In each treatment, 20 rhizome buds were used with 3 replications. All experiments were performed twice. The decontamination rate was recorded at 7 days after incubation, and the survival rate of explants was determined at 3 weeks after incubation.

3.1.3. Shoot Multiplication

Buds were excised from 100 mg L−1 Ag2O NPs treated K. parviflora rhizomes cultured on MS nutrient medium containing 0–12 µM TDZ, 6-furfuryladenine (6-KN), or 6-BA and 8 µM 6-BA. The basal medium was then combined with 2 µM, 4 µM, and 6 µM 6-KN; 0.5 µM, 1 µM, and 2 µM TDZ; or 0.5 µM TDZ and 1 µM, 2 µM, or 4 µM Naphthalene-1-acetic acid (NAA) to induce multiple shoots. These cultures were kept for 8 weeks at 24 ± 1 °C with a 16 h/8 h light/dark photoperiod (40–45 µmol m−2 s−1) provided by cool white fluorescent tubes. Experiments were conducted as a CRD (20 rhizome buds were used in each treatment, 3 replications). All experiments were performed twice. Regeneration rate, number of shoots per rhizome bud, and number of roots per induced shoot were assessed after 8 weeks of incubation.

3.1.4. Rooting and Acclimatization

Four-week-old in vitro-induced shoots (≥2–3 cm in height) were obtained from shoot clusters and cultivated on nutrient medium MS containing 0–12 µM Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) to induce the growth of shoots and roots. After 6 weeks, the number of roots, lengths of roots, and lengths of shoots were recorded. Plantlets were removed from the medium MS containing 2 µM IBA, cleaned with tap water, and transplanted into plastic trays containing sterile soilless substrates composed of 40% peat moss, 30% perlite, and 30% vermiculite based on volume. They were kept in a growth room at 24 ± 1 °C with a 16 h/8 h light/dark photoperiod (90 µmol m−2 s−1) and irrigated at 3-day intervals. The survival of plants was recorded after 5 weeks. Experiments were conducted as a CRD (50 shoots or plantlets for each treatment with three replications). All experiments were performed twice.

3.2. Phytochemical Analysis

3.2.1. Extract Preparation

Leaves of K. parviflora were collected from in vitro cultured plantlets (56 days old) and greenhouse-grown plants (90 days old), minced, stored at −70 °C for 12 h, and lyophilized. Dried leaf powder samples of K. parviflora (50 mg) were extracted with 80% methanol using an Ultraturrax at 6000 g for 30 min. After filtration, extracts were dried using a rotary vacuum evaporator and kept at 4 °C until further investigation.

3.2.2. Estimation of Total Phenolics Content (TPC) and Flavonoids Content (TFC)

TPC of K. parviflora leaf extract was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu assay described by Slinkard and Singleton [73] and calculated as mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE). TFC of K. parviflora leaf extract was determined using the aluminum chloride (AlCl3) technique according to Zengin et al. [74] and expressed as mg of rutin equivalent (RE).

3.2.3. Chemical Characterization

Chromatographic separation was accomplished with a Dionex Ultimate 3000RS UHPLC instrument equipped with a Thermo Accucore C18 (100 mm × 2.1 mm i. d., 2.6 μm) analytical column for separation of compounds. Water (A) and methanol (B) containing 0.1% formic acid were employed as mobile phases. The total run time was 70 min. The elution profile and exact analytical conditions have been published [75]. Electrospray ionization (ESI) was performed in both negative and positive ion modes to obtain more data. Mass spectra were recorded between m/z 100 and 1500 atomic mass units using a Q-Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Chemical constituents were identified by comparison with authentic standards and their MS/MS spectra as well as fragmentation patterns. Peaks and spectra were processed using the TraceFinder software and tentatively identified by comparing their (Rt) retention time and mass spectrum based on reported data and library search.

3.3. Biological Activities of K. parviflora Leaf Extracts

3.3.1. Antioxidant Assay

Several antioxidant assays, such as 2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC), ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), metal chelating ability (MCA), and phosphomolybdenum (PBD), were carried out to determine the antioxidant potential of K. parviflora leaf extract using published methods [76]. Assays were performed in triplicate.

3.3.2. Enzyme Inhibition Assay

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), amylase, and butylcholinestrase (BChE), and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of K. parviflora leaf extract were conducted in triplicates according to procedures described by Uysal et al. [76].

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC, USA). Significant difference among means was determined by analysis of variance and Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT).

4. Conclusions

Treatment of K. parviflora rhizome buds with AgO NPs solution resulted in excellent surface sterilization. Among all cytokinins (6-BA, 6-KN, TDZ) and their concentrations (1–12 µM) evaluated, 8 µM of 6-BA yielded the best explant response. The supplementation of 6-KN (2 µM and 4 µM) or TDZ (0.5–2 µM) to medium MS containing 8 µM 6-BA enhanced the explant response and the number of shoots. The addition of IBA to rooting medium MS improved rooting quality. Higher levels of phenolics and flavonoids were found in leaves from the greenhouse and in vitro cultures, respectively. Leaf extracts exhibited free radical scavenging and enzyme inhibitory activities in in vitro assays. Phytochemical and biological activities of K. parviflora leaf extracts are reported in this study for the first time. Further studies are needed to quantify individual flavonoids in leaf tissues. The micropropagation protocol optimized in the current study can be used for mass-clonal propagation of K. parviflora.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by the KU Research Professor Program of Konkuk University.

Author Contributions

H.-Y.P., K.S., D.-H.K., and I.S. designed the research, I.S., K.S., K.A., G.A., G.Z., Z.C., and J.J. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript, K.-S.K. analyzed the data, H.-Y.P., D.-H.K., K.A., G.A., G.Z., and I.S. edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yenjai C., Prasanphen K., Daodee S., Wongpanich V., Kittakoop P. Bioactive flavonoids from Kaempferia parviflora. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rujjanawate C., Kanjanapothi D., Amornlerdpison D., Pojanagaroon S. Anti-gastric ulcer effect of Kaempferia parviflora. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:120–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akase T., Shimada T., Terabayashi S., Ikeya Y., Sanada H., Aburada M. Antiobesity effects of Kaempferia parviflora in spontaneously obese type II diabetic mice. J. Nat. Med. 2011;65:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11418-010-0461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thao N.P., Luyen B.T.T., Lee S.H., Jang H.D., Kim Y.H. Anti-osteoporotic and antioxidant activities by rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora wall. Ex Baker. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2016;22:13–19. doi: 10.20307/nps.2016.22.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi S., Kato T., Azuma T., Kikuzaki H., Abe K. Anti-allergenic activity of polymethoxyflavones from Kaempferia parviflora. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;13:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paramee S., Sookkhee S., Sakonwasun C., Na Takuathung M., Mungkornasawakul P., Nimlamool W., Potikanond S. Anti-cancer effects of Kaempferia parviflora on ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;18:178. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2241-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawasdee P., Sabphon C., Sitthiwongwanit D., Kokpol U. Anticholinesterase activity of 7-methoxyflavones isolated from Kaempferia parviflora. Phytother. Res. 2009;23:1792–1794. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tewtrakul S., Subhadhirasakul S., Karalai C., Ponglimanont C., Cheenpracha S. Anti-inflammatory effects of compounds from Kaempferia parviflora and Boesenbergia pandurata. Food Chem. 2009;115:534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshino S., Awa R., Miyake Y., Fukuhara I., Sato H., Ashino T., Tomita S., Kuwahara H. Daily intake of Kaempferia parviflora extract decreases abdominal fat in overweight and preobese subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018;11:447–458. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S169925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azuma T., Kayano S.-I., Matsumura Y., Konishi Y., Tanaka Y., Kikuzaki H. Antimutagenic and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of constituents from Kaempferia parviflora. Food Chem. 2011;125:471–475. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutthanut K., Sripanidkulchai B., Yenjai C., Jay M. Simultaneous identification and quantitation of 11 flavonoid constituents in Kaempferia parviflora by gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1143:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakao K., Murata K., Deguchi T., Itoh K., Fujita T., Higashino M., Yoshioka Y., Matsumura S.-I., Tanaka R., Shinada T. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities and crystal structures of methoxyflavones from Kaempferia parviflora rhizome. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011;34:1143–1146. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horigome S., Maeda M., Ho H.-J., Shirakawa H., Komai M. Effect of Kaempferia parviflora extract and its polymethoxyflavonoid components on testosterone production in mouse testis-derived tumour cells. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;26:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochiai W., Kobayashi H., Kitaoka S., Kashiwada M., Koyama Y., Nakaishi S., Nagai T., Aburada M., Sugiyama K. Effect of the active ingredient of Kaempferia parviflora, 5, 7-dimethoxyflavone, on the pharmacokinetics of midazolam. J. Nat. Med. 2018;72:607–614. doi: 10.1007/s11418-018-1184-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azuma T., Tanaka Y., Kikuzaki H. Phenolic glycosides from Kaempferia parviflora. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2743–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaipech S., Morikawa T., Ninomiya K., Yoshikawa M., Pongpiriyadacha Y., Hayakawa T., Muraoka O. Structures of two new phenolic glycosides, kaempferiaosides A and B, and hepatoprotective constituents from the rhizomes of Kaempferia parviflora. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2012;60:62–69. doi: 10.1248/cpb.60.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pripdeevech P., Pitija K., Rujjanawate C., Pojanagaroon S., Kittakoop P., Wongpornchai S. Adaptogenic-active components from Kaempferia parviflora rhizomes. Food Chem. 2012;132:1150–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sulaiman M.R., Zakaria Z.A., Duad I.A., Hidayat M.T. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of the aqueous extract of Kaempferia galanga leaves in animal models. J. Nat. Med. 2008;62:221–227. doi: 10.1007/s11418-007-0210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali M.S., Dash P.R., Nasrin M. Study of sedative activity of different extracts of Kaempferia galanga in Swiss albino mice. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2015;15:158. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0670-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labrooy C.D., Abdullah T.L., Abdullah N.A.P., Stanslas J. Optimum shade enhances growth and 5,7-dimethoxyflavone accumulation in Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2016;213:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2016.10.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prathanturarug S., Apichartbutra T., Chuakul W., Saralamp P. Mass propagation of Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker by in vitro regeneration. J. Hort. Sci. Biotechnol. 2007;82:179–183. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2007.11512217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labrooy C., Abdullah T.L., Stanslas J. Influence of N6-benzyladenine and sucrose on in vitro direct regeneration and microrhizome induction of Kaempferia parviflora Wall. ex Baker, an important ethnomedicinal herb of Asia. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2020;31:123–139. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2020.31.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chirangini P., Sinha S.K., Sharma G.J. In vitro propagation and microrhizome induction in Kaempferia galanga Linn. and K. rotunda Linn. Indian J. Biotech. 2005;4:404–408. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohanty S., Parada R., Singh S., Joshi R.K., Subudhi E., Nabak S. Biochemical and molecular profiling of micropropagated and conventionally grown Kaempferia galanga. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011;106:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9891-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuraida A.R., Izzati K.F.L., Nazreena O.A., Omar N. In vitro microrhizome formation in Kaempferia parviflora. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2015;5:460–467. doi: 10.9734/ARRB/2015/13950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuraida A.R., Nazreena O.A., Izzati K.F.L., Aziz A. Establishment and optimization growth of shoot buds-derived callus and suspension cell cultures of Kaempferia parviflora. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014;5:2693. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2014.518284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murashige T., Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim D.H., Gopal J., Sivanesan I. Nanomaterials in plant tissue culture: The disclosed and undisclosed. RSC Adv. 2017;7:36492–36505. doi: 10.1039/C7RA07025J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D.H., Enkhtaivan G., Saini R.K., Keum Y.S., Kang K.W., Sivanesan I. Production of bioactive compounds in cladode culture of Turbinicarpus valdezianus (H.Moeller) Glass & R. C. Foster. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019;138:111491. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang H., Kang K.W., Kim D.H., Sivanesan I. In vitro propagation of Gastrochilus matsuran (Makino) Schltr., an endangered epiphytic orchid. Plants. 2020;9:524. doi: 10.3390/plants9040524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song K., Sivanesan I., Ak G., Zengin G., Cziáky Z., Jekő J., Rengasamy K.R.R., Lee O.N., Kim D.H. Screening of bioactive metabolites and biological activities of calli, shoots, and seedlings of Mertensia maritima (L.) Gray. Plants. 2020;9:1551. doi: 10.3390/plants9111551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haque S.M., Ghosh B. Micropropagation of Kaempferia angustifolia Roscoe: An aromatic, essential oil yielding, underutilized medicinal plant of Zingiberaceae family. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2018;21:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s12892-017-0051-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leifert C., Cassells A.C. Microbial hazards in plant tissue and cell cultures. In vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant. 2001;37:133–138. doi: 10.1007/s11627-001-0025-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L., Hu C., Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2017;12:1227–1249. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S121956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arab M., Yadollahi M., Hosseini-Mazinani A., Bagheri S. Effects of antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles on in vitro establishment of G × N15 (hybrid of almond × peach) rootstock. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2014;12:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McShan D., Ray P.C., Yu H. Molecular toxicity mechanism of nanosilver. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014;22:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarmast M., Salehi H., Khosh-Khui M. Nano silver treatment is effective in reducing bacterial contaminations of Araucaria excelsa R. Br. var. glauca explants. Acta Biol. Hung. 2011;62:477–484. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.62.2011.4.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahlawat J., Sehrawat A.R., Choudhary R., Yadav S.H. Biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles eclipse fungal and bacterial contamination in micropropagation of Capparis decidua (FORSK.) Edgew: A substitute to toxic substances. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2020;58:336–343. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdi G., Salehi H., Khosh-Khui M. Nano silver: A novel nanomaterial for removal of bacterial contaminants in valerian (Valeriana officinalis L.) tissue culture. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2008;30:709–714. doi: 10.1007/s11738-008-0169-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song K., Kim D.H., Sivanesan I. Effect of plant growth regulators on micropropagation of Hosta minor (Baker) Nakai through shoot tip culture. Propag. Ornam. Plants. 2020;20:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D.H., Sivanesan I. Somatic embryogenesis in Hosta minor (Baker) Nakai. Propag. Ornam. Plants. 2019;19:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arigundam U., Variyath A.M., Siow Y.L., Marshall D., Debnath S.C. Liquid culture for efficient in vitro propagation of adventitious shoots in wild Vaccinium vitis-idaea ssp. minus (lingonberry) using temporary immersion and stationary bioreactors. Sci. Hortic. 2020;264:109199. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chithra M., Martin K.P., Sunandakumari C., Madhusoodanan P.V. Protocol for rapid propagation and to overcome delayed rhizome formation in field established in vitro derived plantlets of Kaempferia galanga L. Sci. Hortic. 2005;104:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2004.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohanty P., Behera S., Swain S.S., Barik D.P., Naik S.K. Micropropagation of Hedychium coronarium (J.) Koenig through rhizome bud. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2013;19:605–610. doi: 10.1007/s12298-013-0199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Behera S., Kamila P.K., Rout K.K., Barik D.P., Panda P.C., Naik S.K. An efficient plant regeneration protocol of an industrially important plant, Hedychium coronarium J. Koenig and establishment of genetic and biochemical fidelity of the regenerants. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;126:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.09.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parida R., Mohanty S., Nayak S. In vitro plant regeneration potential of genetically stable Globba marantina L., Zingiberaceous species and its conservation. Proc. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B. 2018;88:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s40011-016-0759-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jena S., Ray A., Sahoo A., Sahoo S., Kar B., Panda P.C., Nayak S. High-frequency clonal propagation of Curcuma angustifolia ensuring genetic fidelity of micropropagated plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018;135:473–486. doi: 10.1007/s11240-018-1480-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jing H., Strader L.C. Interplay of auxin and cytokinin in lateral root development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:486. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ionkova I. Optimization of flavonoid production in cell cultures of Astragalus missouriensis Nutt. (Fabaceae) Pharmacogn. Mag. 2009;5:92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiao J., Gai Q.Y., Wang X., Qin Q.P., Wang Z.Y., Liu J., Fu Y.J. Chitosan elicitation of Isatis tinctoria L. hairy root cultures for enhancing flavonoid productivity and gene expression and related antioxidant activity. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;124:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gharari Z., Bagheri K., Danafar H., Sharafi A. Enhanced flavonoid production in hairy root cultures of Scutellaria bornmuelleri by elicitor induced over-expression of MYB7 and FNSП2 genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020;148:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krongrawa W., Limmatvapirat S., Saibua S., Limmatvapirat C. Effects of gamma irradiation under vacuum and air packaging atmospheres on the phytochemical contents, biological activities, and microbial loads of Kaempferia parviflora rhizomes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020;173:108947. doi: 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2020.108947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi M.H., Kim K.H., Yook H.S. Antioxidant activity and development of cosmetic materials of solvent extracts from Kaempferia parviflora. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018;47:414–421. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2018.47.4.414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bibi Sadeer N., Montesano D., Albrizio S., Zengin G., Mahomoodally M.F. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety—Chemistry, applications, strengths, and limitations. Antioxidants. 2020;9:709. doi: 10.3390/antiox9080709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arumugam R., Sarikurkcu C., Mutlu M., Tepe B. Sophora alopecuroides var. alopecuroides: Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory activity of the methanolic extract of aerial parts, flowers, leaves, roots, and stems. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan Z., Wang Y., Yang M., Cao J., Khan A., Cheng G. UHPLC-ESI-HRMS/MS analysis on phenolic compositions of different E Se tea extracts and their antioxidant and cytoprotective activities. Food Chem. 2020;318:126512. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mocan A., Moldovan C., Zengin G., Bender O., Locatelli M., Simirgiotis M., Atalay A., Vodnar D.C., Rohn S., Crișan G. UHPLC-QTOF-MS analysis of bioactive constituents from two Romanian Goji (Lycium barbarum L.) berries cultivars and their antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, and real-time cytotoxicological evaluation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;115:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaiser A.B., Zhang N., Van Der Pluijm W. Global prevalence of type 2 diabetes over the next ten years (2018-2028) Diabetes. 2018;67(Suppl. 1):202. doi: 10.2337/db18-202-LB. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramsay R.R., Tipton K.F. Assessment of enzyme inhibition: A review with examples from the development of monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibitory drugs. Molecules. 2017;22:1192. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papoutsis K., Zhang J., Bowyer M.C., Brunton N., Gibney E.R., Lyng J. Fruit, vegetables, and mushrooms for the preparation of extracts with α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition properties: A review. Food Chem. 2020;338:128119. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun L., Wang Y., Miao M. Inhibition of α-amylase by polyphenolic compounds: Substrate digestion, binding interactions and nutritional intervention. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;104:190–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mishra P., Kumar A., Panda G. Anti-cholinesterase hybrids as multi-target-directed ligands against Alzheimer’s disease (1998–2018) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019;27:895–930. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agunloye O.M., Oboh G. Modulatory effect of caffeic acid on cholinesterases inhibitory properties of donepezil. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2017;15:20170016. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2017-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oboh G., Agunloye O.M., Akinyemi A.J., Ademiluyi A.O., Adefegha S.A. Comparative study on the inhibitory effect of caffeic and chlorogenic acids on key enzymes linked to Alzheimer’s disease and some pro-oxidant induced oxidative stress in rats’ brain-in vitro. Neurochem. Res. 2013;38:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oboh G., Agunloye O.M., Adefegha S.A., Akinyemi A.J., Ademiluyi A.O. Caffeic and chlorogenic acids inhibit key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (in vitro): A comparative study. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015;26:165–170. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2013-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng Y.X., Tian J.H., Yang W.H., Chen S.G., Liu D.H., Fang H.T., Zhang H.L., Ye X.Q. Inhibition mechanism of ferulic acid against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 2020;317:126346. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shahwar D., Rehman S.U., Raza M.A. Acetyl cholinesterase inhibition potential and antioxidant activities of ferulic acid isolated from Impatiens bicolor Linn. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010;4:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu J., Yang H., Chen Y., Lin H., Li Q., Mo J., Bian Y., Pei Y., Sun H. Synthesis, pharmacology and molecular docking of multifunctional tacrine–ferulic acid hybrids as cholinesterase inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018;33:496–506. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1430691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ademosun A.O., Oboh G., Bello F., Ayeni P.O. Antioxidative properties and effect of quercetin and its glycosylated form (Rutin) on acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase activities. J. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016;21:11–15. doi: 10.1177/2156587215610032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dubey S., Ganeshpurkar A., Ganeshpurkar A., Bansal D., Dubey N. Glycolytic enzyme inhibitory and antiglycation potential of rutin. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;3:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fjps.2017.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martinez-Gonzalez A.I., Díaz-Sánchez Á.G., de La Rosa L.A., Bustos-Jaimes I., Alvarez-Parrilla E. Inhibition of α-amylase by flavonoids: Structure activity relationship (SAR). Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;206:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yong N.L., Ahmad A., Mohammad A.W. Synthesis and characterization of silver oxide nanoparticles by a novel method. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013;4:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slinkard K., Singleton V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1977;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zengin G., Sarikurkcu C., Aktumsek A., Ceylan R. Sideritis galatica Bornm.: A source of multifunctional agents for the management of oxidative damage, Alzheimer’s’s and diabetes mellitus. J. Funct. Foods. 2014;11:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zengin G., Uysal A., Diuzheva A., Gunes E., Jekő J., Cziáky Z., Picot-Allain C.M.N., Mahomoodally M.F. Characterization of phytochemical components of Ferula halophila extracts using HPLC-MS/MS and their pharmacological potentials: A multi-functional insight. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 2018;60:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uysal S., Zengin G., Locatelli M., Bahadori M.B., Mocan A., Bellagamba G., De Luca E., Mollica A., Aktumsek A. Cytotoxic and enzyme inhibitory potential of two Potentilla species (P. speciosa L. and P. reptans Willd.) and their chemical composition. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:290. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]