Abstract

Background: Bisphenol A (BPA), a reprotoxic and endocrine-disrupting chemical, has been substituted by alternative bisphenols such as bisphenol F (BPF) and bisphenol S (BPS) in the plastic industry. Despite their detection in placenta and amniotic fluids, the effects of bisphenols on human placental cells have not been characterized. Our objective was to explore in vitro and to compare the toxicity of BPA to its substitutes BPF and BPS to highlight their potential risks for placenta and then pregnancy. Methods: Human placenta cells (JEG-Tox cells) were incubated with BPA, BPF, and BPS for 72 h. Cell viability, cell death, and degenerative P2X7 receptor and caspases activation, and chromatin condensation were assessed using microplate cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. Results: Incubation with BPA, BPF, or BPS was associated with P2X7 receptor activation and chromatin condensation. BPA and BPF induced more caspase-1, caspase-9, and caspase-3 activation than BPS. Only BPF enhanced caspase-8 activity. Conclusions: BPA, BPF, and BPS are all toxic to human placental cells, with the P2X7 receptor being a common key element. BPA substitution by BPF and BPS does not appear to be a safe alternative for human health, particularly for pregnant women and their fetuses.

Keywords: human placental toxicity, bisphenol A, bisphenol F, bisphenol S, P2X7 receptor, inflammasome, apoptosis

1. Introduction

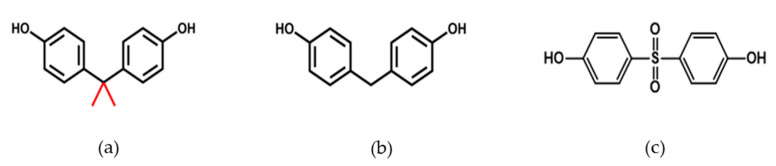

Bisphenol A (BPA; 4,4′-(propane-2,2-diyl)diphenol) is a phenolic compound discovered in the late nineteenth century, used in the manufacturing of polycarbonates, epoxyresins, and other polymers. It is therefore found in a wide range of products such as food and beverage containers, compact discs, personal protective equipment, sport equipment, and medical equipment, leading to multiple sources of exposure for the entire population. In humans, BPA is detected in the blood and urine, but it is also found in the placenta and amniotic fluid [1,2,3]. BPA has been listed as a substance of very high concern (SVHC) under the registration, evaluation, authorization and restriction of chemicals (REACh) legislation, first because of its reprotoxic properties and then because of its endocrine-disrupting properties. Its use has been limited and banned in baby bottles in Canada (2008), France (2010), and European Union (2011). In France, since January 2015, BPA has been forbidden in food and beverage packaging. These restrictions led manufacturers to use alternative bisphenols such as bisphenol F (BPF; bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)methane); Figure 1b) and bisphenol S (BPS; bis[4-hydroxyphenyl]sulfone; Figure 1c). According to the European Agency (ECHA), 187 kilotons of BPS-based thermal paper were placed on the EU market in 2019. By 2022, it is expected that 61% (or 307 kilotons) of all thermal paper in the EU will be BPS-based. However, despite the increasing use of BPA structural analogs, there is limited information on the potential placental and fetal toxicity of these molecules.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of: (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS.

The placenta is a crucial organ for pregnancy, acting as an endocrine organ and being an interface between the mother and the fetus. Consequently, it plays a central role in the health of the fetus, and has a lifelong impact on their future wellbeing. Disordered placental development is the primary defect in the majority of pregnancy diseases, such as preeclampsia (considered the leading cause of maternal and fetal death worldwide), fetal growth restriction, recurrent miscarriage, and stillbirth [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The link between preeclampsia and BPA exposure has not been clearly established yet, but concentrations of BPA are higher in women suffering from preeclampsia [3,11]. It has also been published that BPA affects the placenta in mice and therefore alters fetal programming [12]. Benachour et al. showed in vitro that even very low concentrations of BPA are able to induce apoptosis, necrosis, and inflammation in human trophoblastic cells [13]. The question that we raise is: Could BPA analogs also be at the origin of preeclampsia through the induction of trophoblast death? At the cell level, it has been suggested that preterm birth [14] and preeclampsia [15] are triggered by P2X7 receptor activation. The activation of the P2X7 receptor, expressed by placental cells [16], leads to different pathways that are implicated in preeclampsia, including apoptosis and necrosis [17], and inflammation with NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 activation [18]. In light of the above, the P2X7 receptor seems to be a good marker of placental toxicity.

Our aim was to compare bisphenol A toxicity to its substitutes, bisphenol F and bisphenol S, on their ability to induce in vitro cell death in human placental cells, at concentrations that can be found in the placenta, in order to highlight the potential risks for the placenta and then pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents. Cell culture reagents: Minimum essential medium (MEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA 0.05%, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were provided by Gibco (Paisley, U.K.), and cell culture material such as flasks and microplates by Corning (Schiphol-Rijk, The Netherlands). YO-PRO-1®, CellEventTM Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent and Hoechst 33342 probes were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), while Caspase-Glo® 1 Inflammasome Assay, Caspase-Glo® 8 Assay, and Caspase-Glo® 9 Assay were from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France).

Bisphenol A, bisphenol F, and bisphenol S were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxyde (DMSO). Stock solutions were stored at −20 °C and work solutions were obtained after a 1/1000 dilution in culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO on cells was less than or equal to 0.1%.

Human placental cell culture. JEG-3 cells were selected in our study for several reasons. Primary cultures of human placental cells, in addition to being difficult to obtain and maintain in culture, may have been exposed to BPA, BPF, and BPS or other chemicals during pregnancy, which would lead to bias in data analysis. Several human placental cell lines are available in international collections such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Previous studies have shown that the JEG-3 cell line provides an appropriate model to detect placental toxicity [19,20]. JEG-3 cells are furthermore able to synthesize and secrete hormones [20,21]. For BPA, being an endocrine disrupting chemical, JEG-3 cells are the best option to compare human placental toxicity of bisphenols.

The JEG-3 human trophoblast cell line was obtained from ATCC (HTB-36). Cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin in 75 cm2 polystyrene flasks. Cell cultures were maintained in a cell culture incubator (37 °C, saturated humidity, and 5% CO2). When the JEG-3 cells reached subconfluency, they were detached using trypsin-EDTA and counted. The cellular suspension was diluted and seeded in 96-well microplates at a cellular density of 80,000 cells/mL (200 µL/well), then kept at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were incubated for 72 h with BPA, BPF, and BPS in MEM supplemented with 2.5% FBS according to Olivier et al.’s protocol that describes the JEG-Tox model [20].

Cell viability: Neutral Red assay. The Neutral Red solution at 0.4% (m/v in water) was diluted in cell culture medium to obtain a working concentration of 50 μg/mL. Neutral Red working solution was distributed in the plates for a 3 h incubation time at 37 °C. The cells were then rinsed with PBS and lysed with a solution of ethanol–water–acetic acid (50.6/48.4/1, v/v/v). After homogenization, the fluorescence signal was scanned (λexc = 540 nm and λem = 600 nm) using a Spark® microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

P2X7 receptor expression: Western blot technique. Cell lysates were prepared by washing the cells twice in cold PBS, lysing them in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min on ice, and then, the obtained lysates were sonicated for 30 s. The total protein concentration was determined using the Pierce® microBCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofisher Scientific). Protein sample buffer and reducing agent were added and the samples were boiled at 70 °C for 10 min. Then, 40 μg of these samples was loaded and electrophoretically separated on 4–12% polyacrylamide gels (BoltTM Bis-Tris Plus, Thermofisher Scientific), before being transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (iBlot™ 2 Transfer Stack, 0.2 μm Nitrocellulose, ThermoFisher Scientific) using iBlot™ 2 Gel transfer device (ThermoFisher Scientific). Blots were incubated first using a primary polyclonal rabbit anti-P2X7 at 1:1000 (overnight, catalog #PA5-25581, ThermoFisher Scientific) and then a secondary DyLight 800 Fluor-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody at 1:15,000 for 1 h (ThermoFisher Scientific). Actin was used as a housekeeping protein for the normalization of data using an anti-actin polyclonal antibody at 1:1000 (catalog #PA5-11570, ThermoFisher Scientific). Blots were scanned using Odyssey® Imaging System (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Quantitation of bands was performed using ImageJ software.

Cell death P2X7 receptor activation: YO-PRO-1® assay. P2X7 cell death receptor activation was evaluated using the YO-PRO-1® assay [22]. YO-PRO-1® probe only enters into cells after pore opening induced by P2X7 receptor activation, and binds to DNA, emitting fluorescence. A 1 mM YO-PRO-1® stock solution was diluted at 1/500 in PBS just before use and distributed in the wells of the microplate. After a 10 min incubation time at room temperature, the fluorescence signal was read (λex = 485 nm and λem = 531 nm) using a Spark® microplate reader.

Caspase-1, -8, and -9 activity: Caspase-Glo® Assays. Caspase-1, -8, and -9 activity was evaluated using the Caspase-Glo® 1, 8, and 9 Assay Kits, respectively. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was quantified using a Spark® microplate reader.

Caspase 3 activity: CellEventTM Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent. Caspase-3 activity was evaluated using the CellEventTM Caspase3/7 Green Detection Reagent. Cell EventTM Caspase-3/7 Green Detection reagent was diluted in PBS with 2.5% FBS to a final concentration of 8 μM. The cells were incubated with the reagent for 30 min and then rinsed with PBS. The cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy and pictures were taken (Evos FL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of chromatin condensation: Hoechst 33342 assay. Chromatin condensation was evaluated using the Hoechst 33342 assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Illkirch, France). Hoechst 33342 fluorescent probe enters and intercalates into DNA in living and apoptotic cells. The fluorescent signal is proportional to chromatin condensation, and the nuclei of living cells are blue, while the nuclei of apoptotic cells are bright [20,23,24]. A 0.5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 solution was distributed in the wells of the microplate. The fluorescence signal was read after a 30 min incubation time at room temperature (λex = 350 nm and λem = 450 nm) using a Spark® microplate reader, and the cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy and pictures were taken (Evos FL, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Results exploitation and statistical analysis. The results are expressed in percentage or fold change compared to control cells and presented as means of at least three independent experiments ± standard errors of the mean.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). A one-way analysis of variance for repeated measures followed by a Dunnett’s test with risk α set at 5% were performed. Thresholds of significance were **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05 compared to control cells.

3. Results

3.1. Cell Viability

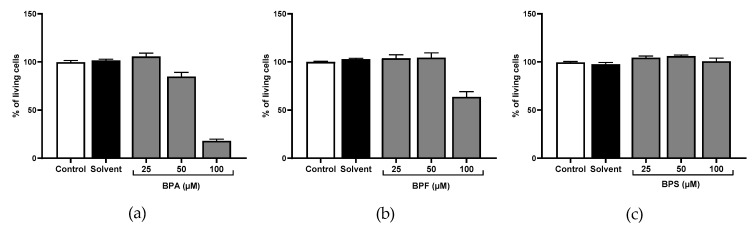

We investigated JEG-Tox cell viability after incubation with bisphenols using the Neutral Red assay. Any concentration inducing a loss of cell viability greater than or equal to 30% was considered as cytotoxic (ISO 2009). Therefore, no statistical analysis was performed.

No loss of cell viability was observed after 72 h with BPS up to 100 μM (Figure 2c). In contrast, BPA and BPF at 100 μM reduced cell viability to 18% and 64%, respectively (Figure 2a,b), and were thus cytotoxic at 100 μM. To evaluate subcytotoxic concentrations, BPA and BPF at 100 μM were suppressed in the rest of the study.

Figure 2.

Cell viability was evaluated using the Neutral Red assay after (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of four independent experiments.

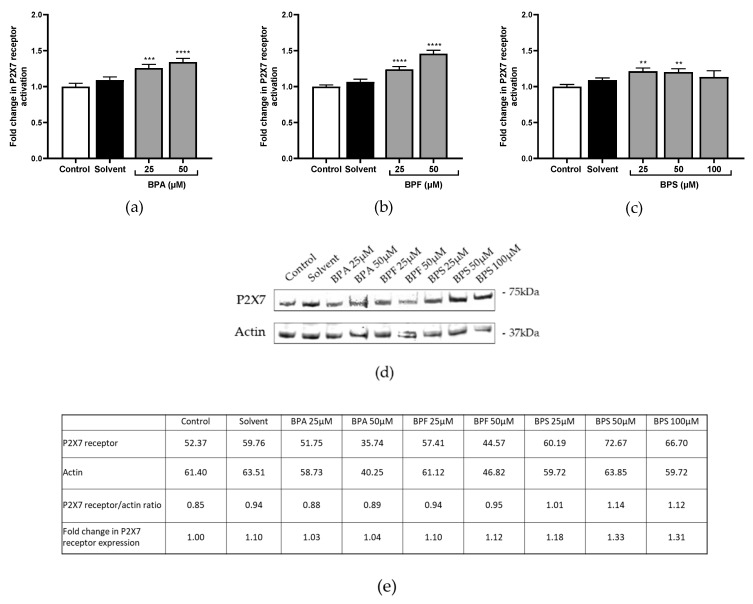

3.2. P2X7 Receptor Activation and Expression

P2X7 pore opening, reflecting P2X7 receptor activation, was assessed using the fluorescent YO-PRO-1® assay. P2X7 receptor was significantly activated by the three tested bisphenols. BPA and BPF induced similar levels of P2X7 activation in a concentration-dependent manner (×1.26 at 25 μM and ×1.34 at 50 μM in Figure 3a; ×1.24 at 25 μM and ×1.46 at 50 μM compared to the control in Figure 3b). BPS induced slighter activation than the two other bisphenols (×1.21 and ×1.20 at 25 μM and 50 μM, respectively; Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

(a–c) P2X7 receptor activation was evaluated after (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ±SEM of four independent experiments. The significance thresholds were **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.001, and ** p < 0.01 compared to the control. (d,e) P2X7 receptor expression was assessed after BPA, BPF, and BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells (d) using the Western blot technique, and (e) quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software. β-actin was used as a control.

P2X7 receptor expression was investigated after incubation with bisphenols using the Western blot technique. Only BPS enhanced P2X7 receptor expression compared to the control (×1.18 at 25 μM, ×1.33 at 50 μM, and ×1.31 at 100 μM; Figure 3d).

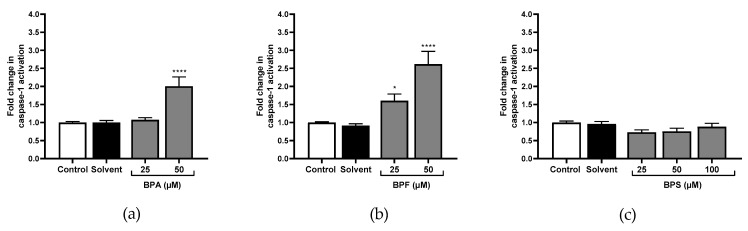

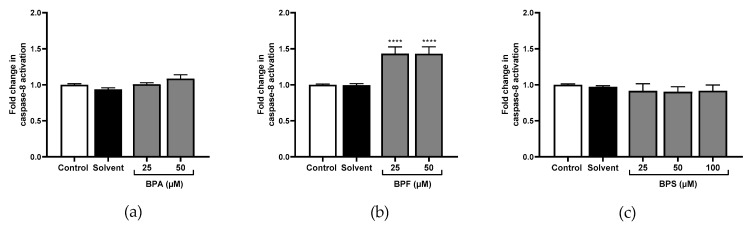

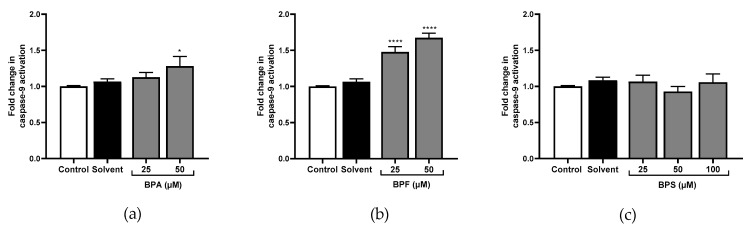

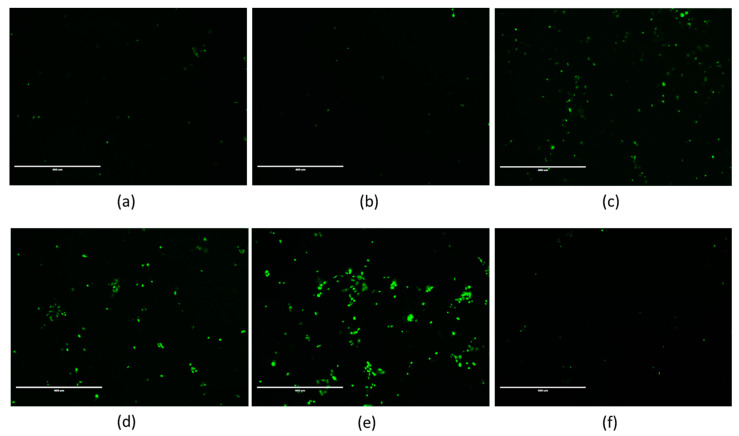

3.3. Caspase-1, Caspase-8, Caspase-9, and Caspase-3 Activity

The bioluminescent Caspase-Glo® 1 inflammasome, Caspase-Glo® 8, and Caspase-Glo® 9 assays were used to quantify caspase-1, caspase-8, and caspase-9 activity, respectively, and the fluorescence CellEvent® Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent was used to analyze caspase-3 activity by microscopy.

Only the highest concentration of BPA significantly activated caspase-1 (×1.57 at 50 μM; Figure 4a). No effect was observed for caspase-8 (Figure 5a). However, caspase-9 (×1.28; Figure 6a), and caspase-3 (Figure 7c) were significantly activated by the highest concentration of BPA.

Figure 4.

Caspase-1 activity cells was evaluated in JEG-Tox after incubation with (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. The significance thresholds were **** p < 0.0001 and * p < 0.05 compared to the control.

Figure 5.

Caspase-8 activity cells was evaluated in JEG-Tox after incubation with (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ±SEM of four independent experiments. The significance threshold was **** p < 0.0001compared to the control.

Figure 6.

Caspase-9 activity cells was evaluated in JEG-Tox after incubation with (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. The significance thresholds were **** p < 0.0001 and * p < 0.05 compared to the control.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence microscopy images of JEG-Tox cells stained for caspase-3/7 activity. After 72 h of incubation with (a) the control, (b) solvent, (c) 50 μM of BPA, (d,e) 25 μM and 50 μM of BPF, respectively, and (f) 100 μM of BPS, the cells were stained using Caspase-3/7 Green Detection Reagent. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. The images were captured under the same acquisition parameters by Evos FL fluorescence microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

All tested concentrations of BPF significantly activated caspase-1 compared to the control (×1.60 and ×2.61 at 25 μM and 50 μM respectively; Figure 4b). Caspase-8 was also significantly activated at 25 μM and 50 μM of BPF (×1.43; Figure 5b), and so was caspase-9 (×1.47 and ×1.67, respectively; Figure 6b). Caspase-3 activity was higher with 25 μM and 50 μM of BPF than the control (Figure 7d,e).

BPS had no effect on caspase-1 (Figure 4c), caspase-8, or caspase-9 activities (Figure 5c and Figure 6c), nor caspase-3 activities (Figure 7f).

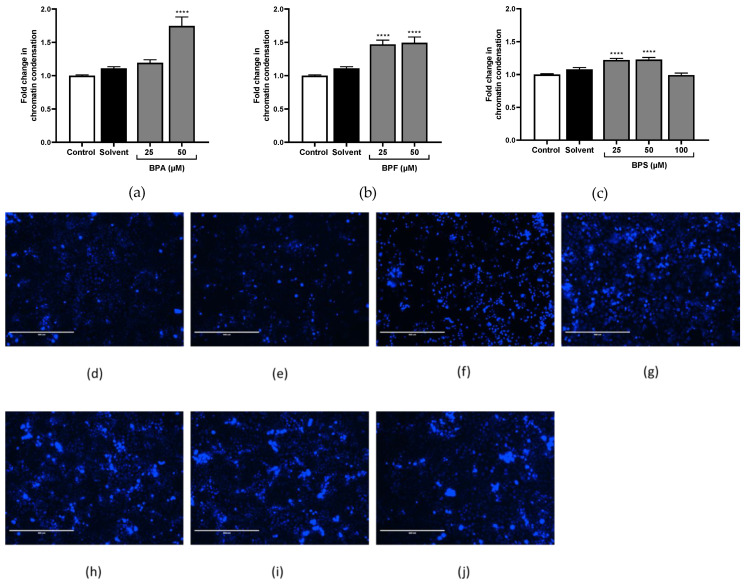

3.4. Chromatin Condensation

The three tested bisphenols condensed significantly the chromatin. BPA induced the most chromatin condensation, but only at 50 μM (×1.79; Figure 8a,f). BPF triggered chromatin condensation at two tested concentrations (×1.47 and 1.49 at 25 μM and 50 μM, respectively; Figure 8b,g,h). BPS induced slighter activation than two other bisphenols, but from 25 μM (×1.22 at 25 μM and 1.23 at 50 μM; Figure 8c,i,j).

Figure 8.

Quantification and qualification of chromatin condensation using Hoechst 33,342 assay. (a–c) Chromatin condensation quantification was assessed after (a) BPA, (b) BPF, and (c) BPS incubation for 72 h in JEG-Tox cells. Data correspond to the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. The significance threshold was **** p < 0.0001 compared to the control. (d–j) Chromatin condensation observation under fluorescence microscopy in JEG-Tox cells after incubation for 72 h with (d) the control, (e) solvent, (f) 50 μM of BPA, (g,h) 25 μM and 50 μM of BPF, respectively, and (i,j) 25 μM and 50 μM of BPS, respectively. The pictures are representative of three independent experiments and were captured under the same acquisition parameters.

4. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to explore and compare the toxicity of BPA to its substitutes BPF and BPS in a human placental cell line to highlight their potential risks for pregnancy.

In humans, BPA is detected in amniotic fluid, neonatal blood, and the placenta at levels of nanograms/mililiter [1,2,3,25,26]. During fetal development, BPA can be accumulated in the placenta and amniotic fluid; indeed, a 5-fold higher concentration was revealed in amniotic fluid than in maternal plasma [25]. BPA was reported to significantly affect fetal development and to increase the risk of adverse health consequences. Associations between BPA exposure and reproductive dysfunction [27,28], obesity [29,30], developmental behavioral problems [31,32], cancers [33,34,35], and placental disorders [3,12,36] have been reported. For all of these reasons, the use of BPA has been limited or banned in several countries, leading to its substitution by analogs, mainly BPF and BPS. Are BPF and BPS truly safe alternatives to BPA? That is a fair question, since BPF is also detected in urine, the uterus, the placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetuses [37,38,39], and BPS in urine, maternal plasma, cord plasma, and placenta samples [38,39,40,41,42], both at levels of nanograms/mililiter [38]. BPS concentrations in the placenta are significantly higher than in maternal plasma [42], suggesting BPS accumulation in the placenta, just like BPA [25,43]. The concentrations of bisphenols used in this study are of the same order of magnitude as those levels.

The present study is the first to demonstrate that BPA, BPF, and BPS are all toxic to placental cells, but with different impacts. In particular, cell viability, P2X7 receptor activation, caspases activation, and chromatin condensation are differently affected by these three bisphenols, despite their structural homology. Previous studies comparing BPF and BPS were focused either on the quantification in the human placenta [42], on the potential transfer across the human placental barrier [44,45,46,47,48], or on their toxic effects in animal models [37,45,46,47,48]. None of them compared the effects of BPA, BPF, or BPS on human placental cell survival. It is of great importance to use human models to study placental toxicity, because the placenta is very different from species to species in terms of form, structure, and endocrine secretion [49].

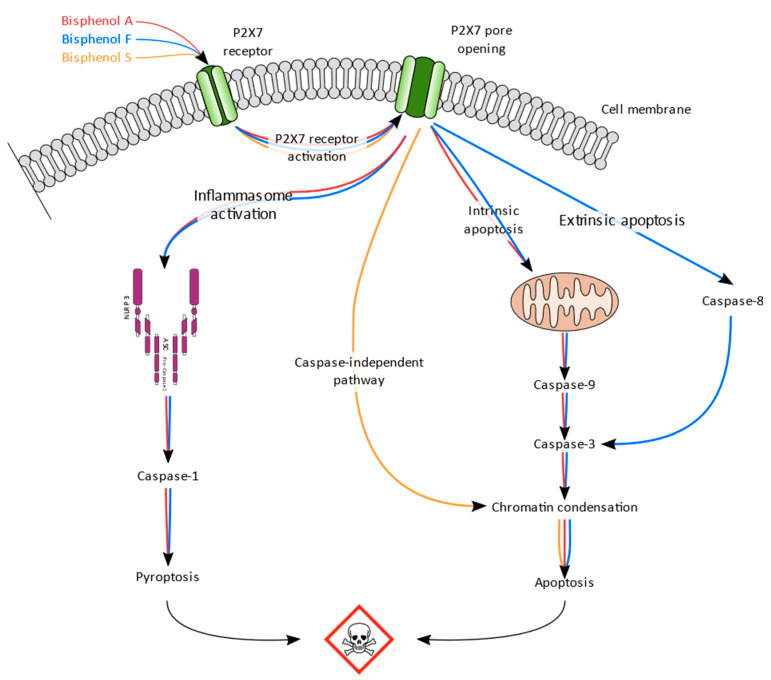

BPA and BPF induced similar levels of P2X7 receptor activation, BPF being slightly more potent than BPA. BPS induced lower activation than both BPA and BPF, but is the only bisphenol that enhanced P2X7 receptor expression. The P2X7 receptor plays a key role in inflammation by NLRP3-inflammasome formation, leading to caspase-1 activation [50,51]. In our model, BPA and BPF significantly activated caspase-1, suggesting their implication in inflammasome induction. Prolonged activation of P2X7 receptor has been linked to apoptosis [52,53]. Depending on the cleaved caspase, apoptosis can be initiated via the extrinsic receptor mediated pathway through caspase-8 activation [54,55] or via the mitochondria-mediated pathway, resulting in caspase-9 activation [53]. Both pathways can be triggered by P2X7 receptor and lead to caspase-3 activation [56], followed by chromatin condensation [57]. Caspase-9 and caspase-3 were significantly activated by BPA and BPF, but only BPF enhanced caspase-8 activity. All tested bisphenols induced chromatin condensation. BPF seems to induce both extrinsic apoptosis mediated by caspase-8 and intrinsic apoptosis mediated by caspase-9, leading to caspase-3 activation and chromatin condensation. BPA only induces intrinsic apoptosis (caspase-9), also leading to caspase-3 activation and chromatin condensation. Contrary to BPA and BPF, BPS enhanced chromatin condensation without activation of caspase 8 or caspase 9, suggesting a caspase-independent mechanism [58].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest that BPA, BPF, and BPS induce toxicity in human placental cells. Despite their structural homology, the induced pathways are different, but they all share P2X7 receptor activation as the key starting event, reported to trigger preeclampsia in clinics (Scheme 1). BPF and BPS are therefore susceptible to inducing the same toxic effects in pregnant women, including preeclampsia, as BPA. BPA substitution by BPF and BPS is not safe for human health, particularly for pregnant women and their fetus.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis scheme of the BPA, BPF, and BPS effects in human placental cells (JEG-Tox cells).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adebiopharm ER67 for their financial support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F., M.D., and E.O.; methodology, S.F.; investigation, S.F. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; writing—review and editing, S.F., M.D., E.O., and P.R.; supervision, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schönfelder G., Wittfoht W., Hopp H., Talsness C.E., Paul M., Chahoud I. Parent Bisphenol A Accumulation in the Human Maternal-Fetal-Placental Unit. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110:A703–A707. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandenberg L.N., Chahoud I., Heindel J.J., Padmanabhan V., Paumgartten F.J.R., Schoenfelder G. Urinary, Circulating, and Tissue Biomonitoring Studies Indicate Widespread Exposure to Bisphenol A. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:1055–1070. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leclerc F., Dubois M.-F., Aris A. Maternal, Placental and Fetal Exposure to Bisphenol A in Women with and without Preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy. 2014;33:341–348. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2014.892607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman-Wohl D., Yagel S. Regulation of Trophoblast Invasion: From Normal Implantation to Pre-Eclampsia. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187:233–238. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebire N.J., Foskett M., Fisher R.A., Rees H., Seckl M., Newlands E. Risk of Partial and Complete Hydatidiform Molar Pregnancy in Relation to Maternal Age. BJOG. 2002;109:99–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.t01-1-01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton G.J., Jauniaux E. Placental Oxidative Stress: From Miscarriage to Preeclampsia. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2004;11:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball E., Bulmer J.N., Ayis S., Lyall F., Robson S.C. Late Sporadic Miscarriage Is Associated with Abnormalities in Spiral Artery Transformation and Trophoblast Invasion. J. Pathol. 2006;208:535–542. doi: 10.1002/path.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duley L. The Global Impact of Pre-Eclampsia and Eclampsia. Semin. Perinatol. 2009;33:130–137. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carty D.M., Delles C., Dominiczak A.F. Preeclampsia and Future Maternal Health. J. Hypertens. 2010;28:1349–1355. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a39d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brosens I., Pijnenborg R., Vercruysse L., Romero R. The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” Are Associated with Disorders of Deep Placentation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;204:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantonwine D.E., Meeker J.D., Ferguson K.K., Mukherjee B., Hauser R., McElrath T.F. Urinary Concentrations of Bisphenol A and Phthalate Metabolites Measured during Pregnancy and Risk of Preeclampsia. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016;124:1651–1655. doi: 10.1289/EHP188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tait S., Tassinari R., Maranghi F., Mantovani A. Bisphenol A Affects Placental Layers Morphology and Angiogenesis during Early Pregnancy Phase in Mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015;35:1278–1291. doi: 10.1002/jat.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benachour N., Aris A. Toxic Effects of Low Doses of Bisphenol-A on Human Placental Cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;241:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsimis M.E., Lei J., Rosenzweig J.M., Arif H., Shabi Y., Alshehri W., Talbot C.C., Baig-Ward K.M., Segars J., Graham E.M., et al. P2X7 Receptor Blockade Prevents Preterm Birth and Perinatal Brain Injury in a Mouse Model of Intrauterine Inflammation. Biol. Reprod. 2017;97:230–239. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fodor P., White B., Khan R. Inflammation-The Role of ATP in Pre-Eclampsia. Microcirculation. 2020;27:e12585. doi: 10.1111/micc.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts V.H.J., Greenwood S.L., Elliott A.C., Sibley C.P., Waters L.H. Purinergic Receptors in Human Placenta: Evidence for Functionally Active P2X4, P2X7, P2Y2, and P2Y6. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;290:R1374–R1386. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00612.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barakonyi A., Miko E., Szereday L., Polgar P.D., Nemeth T., Szekeres-Bartho J., Engels G.L. Cell Death Mechanisms and Potentially Cytotoxic Natural Immune Cells in Human Pregnancies Complicated by Preeclampsia. Reprod. Sci. 2014;21:155–166. doi: 10.1177/1933719113497288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirasuna K., Karasawa T., Takahashi M. Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Preeclampsia. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020;11:80. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakx A., Regazzetti A., Dargère D., Auzeil N., Gil S., Evain-Brion D., Laprévote O., Rat P. New in Vitro Biomarkers to Detect Toxicity in Human Placental Cells: The Example of Benzo[A]Pyrene. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2016;32:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivier E., Wakx A., Fouyet S., Dutot M., Rat P. JEG-3 Placental Cells in Toxicology Studies: A Promising Tool to Reveal Pregnancy Disorders. Anat. Cell Biol. 2020 doi: 10.5115/acb.20.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daoud G., Barrak J., Abou-Kheir W. Assessment Of Different Trophoblast Cell Lines As In Vitro Models For Placental Development. FASEB J. 2016;30:1247.18. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.30.1_supplement.1247.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rat P., Olivier E., Tanter C., Wakx A., Dutot M. A Fast and Reproducible Cell- and 96-Well Plate-Based Method for the Evaluation of P2X7 Receptor Activation Using YO-PRO-1 Fluorescent Dye. J. Biol. Methods. 2017;4:e64. doi: 10.14440/jbm.2017.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chazotte B. Labeling Nuclear DNA with Hoechst 33342. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011;2011:pdb.prot5557. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spagnol S.T., Dahl K.N. Spatially Resolved Quantification of Chromatin Condensation through Differential Local Rheology in Cell Nuclei Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. PLoS ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikezuki Y., Tsutsumi O., Takai Y., Kamei Y., Taketani Y. Determination of Bisphenol A Concentrations in Human Biological Fluids Reveals Significant Early Prenatal Exposure. Hum. Reprod. 2002;17:2839–2841. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.11.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Z.-R., Xu X.-L., Deng S.-L., Lian Z.-X., Yu K. Oestrogenic Endocrine Disruptors in the Placenta and the Fetus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1519. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caserta D., Di Segni N., Mallozzi M., Giovanale V., Mantovani A., Marci R., Moscarini M. Bisphenol a and the Female Reproductive Tract: An Overview of Recent Laboratory Evidence and Epidemiological Studies. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014;12:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng M.J., Wu X.Q., Li J., Ding L., Wang Z.Q., Shen Y., Song Z.C., Wang L., Yang Q., Wang X.P., et al. [Relationship between daily exposure to bisphenol A and male sexual function-a study from the reproductive center] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39:836–840. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legeay S., Faure S. Is Bisphenol A an Environmental Obesogen? Fundam Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;31:594–609. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu B., Lehmler H.-J., Sun Y., Xu G., Liu Y., Zong G., Sun Q., Hu F.B., Wallace R.B., Bao W. Bisphenol A Substitutes and Obesity in US Adults: Analysis of a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e114–e122. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roen E.L., Wang Y., Calafat A.M., Wang S., Margolis A., Herbstman J., Hoepner L.A., Rauh V., Perera F.P. Bisphenol A Exposure and Behavioral Problems among Inner City Children at 7–9 Years of Age. Environ. Res. 2015;142:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbuckle T.E., Davis K., Boylan K., Fisher M., Fu J. Bisphenol A, Phthalates and Lead and Learning and Behavioral Problems in Canadian Children 6–11 Years of Age: CHMS 2007–2009. Neurotoxicology. 2016;54:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seachrist D.D., Bonk K.W., Ho S.-M., Prins G.S., Soto A.M., Keri R.A. A Review of the Carcinogenic Potential of Bisphenol A. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016;59:167–182. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leung Y.-K., Govindarajah V., Cheong A., Veevers J., Song D., Gear R., Zhu X., Ying J., Kendler A., Medvedovic M., et al. Gestational High-Fat Diet and Bisphenol A Exposure Heightens Mammary Cancer Risk. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2017;24:365–378. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu F., Wang X., Wu N., He S., Yi W., Xiang S., Zhang P., Xie X., Ying C. Bisphenol A Induces Proliferative Effects on Both Breast Cancer Cells and Vascular Endothelial Cells through a Shared GPER-Dependent Pathway in Hypoxia. Environ. Pollut. 2017;231:1609–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pergialiotis V., Kotrogianni P., Christopoulos-Timogiannakis E., Koutaki D., Daskalakis G., Papantoniou N. Bisphenol A and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:3320–3327. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1368076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cabaton N., Chagnon M.-C., Lhuguenot J.-C., Cravedi J.-P., Zalko D. Disposition and Metabolic Profiling of Bisphenol F in Pregnant and Nonpregnant Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:10307–10314. doi: 10.1021/jf062250q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehmler H.-J., Liu B., Gadogbe M., Bao W. Exposure to Bisphenol A, Bisphenol F, and Bisphenol S in U.S. Adults and Children: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2014. ACS Omega. 2018;3:6523–6532. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y.-X., Liu C., Shen Y., Wang Q., Pan A., Yang P., Chen Y.-J., Deng Y.-L., Lu Q., Cheng L.-M., et al. Urinary Levels of Bisphenol A, F and S and Markers of Oxidative Stress among Healthy Adult Men: Variability and Association Analysis. Environ. Int. 2019;123:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ihde E.S., Zamudio S., Loh J.M., Zhu Y., Woytanowski J., Rosen L., Liu M., Buckley B. Application of a Novel Mass Spectrometric (MS) Method to Examine Exposure to Bisphenol-A and Common Substitutes in a Maternal Fetal Cohort. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018;24:331–346. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2017.1381831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu L.-H., Zhang X.-M., Wang F., Gao C.-J., Chen D., Palumbo J.R., Guo Y., Zeng E.Y. Occurrence of Bisphenol S in the Environment and Implications for Human Exposure: A Short Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;615:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan Y., Deng M., Li J., Du B., Lan S., Liang X., Zeng L. Occurrence and Maternal Transfer of Multiple Bisphenols, Including an Emerging Derivative with Unexpectedly High Concentrations, in the Human Maternal-Fetal-Placental Unit. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:3476–3486. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta R., Gupta R. Developmental Toxicology. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. Placental Toxicity; pp. 1301–1325. Chapter 68. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J., Li J., Wu Y., Zhao Y., Luo F., Li S., Yang L., Moez E.K., Dinu I., Martin J.W. Bisphenol A Metabolites and Bisphenol S in Paired Maternal and Cord Serum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:2456–2463. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b05718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grandin F.C., Lacroix M.Z., Gayrard V., Viguié C., Mila H., de Place A., Vayssière C., Morin M., Corbett J., Gayrard C., et al. Is Bisphenol S a Safer Alternative to Bisphenol A in Terms of Potential Fetal Exposure? Placental Transfer across the Perfused Human Placenta. Chemosphere. 2019;221:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gingrich J., Pu Y., Roberts J., Karthikraj R., Kannan K., Ehrhardt R., Veiga-Lopez A. Gestational Bisphenol S Impairs Placental Endocrine Function and the Fusogenic Trophoblast Signaling Pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2018;92:1861–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2191-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Da Silva B.S., Pietrobon C.B., Bertasso I.M., Lopes B.P., Carvalho J.C., Peixoto-Silva N., Santos T.R., Claudio-Neto S., Manhães A.C., Oliveira E., et al. Short and Long-Term Effects of Bisphenol S (BPS) Exposure during Pregnancy and Lactation on Plasma Lipids, Hormones, and Behavior in Rats. Environ. Pollut. 2019;250:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao J., Jain A., Denslow N.D., Nouri M.-Z., Chen S., Wang T., Zhu N., Koh J., Sarma S.J., Sumner B.W., et al. Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S Disruptions of the Mouse Placenta and Potential Effects on the Placenta-Brain Axis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:4642–4652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919563117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt A., Morales-Prieto D.M., Pastuschek J., Fröhlich K., Markert U.R. Only Humans Have Human Placentas: Molecular Differences between Mice and Humans. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2015;108:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. The Inflammasome: A Molecular Platform Triggering Activation of Inflammatory Caspases and Processing of ProIL-Beta. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogura Y., Sutterwala F.S., Flavell R.A. The Inflammasome: First Line of the Immune Response to Cell Stress. Cell. 2006;126:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng L.M., Zychlinsky A., Liu C.C., Ojcius D.M., Young J.D. Extracellular ATP as a Trigger for Apoptosis or Programmed Cell Death. J. Cell Biol. 1991;112:279–288. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackenzie A.B., Young M.T., Adinolfi E., Surprenant A. Pseudoapoptosis Induced by Brief Activation of ATP-Gated P2X7 Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33968–33976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrari D., Los M., Bauer M.K., Vandenabeele P., Wesselborg S., Schulze-Osthoff K. P2Z Purinoreceptor Ligation Induces Activation of Caspases with Distinct Roles in Apoptotic and Necrotic Alterations of Cell Death. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:71–75. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aguirre A., Shoji K.F., Sáez J.C., Henríquez M., Quest A.F.G. FasL-Triggered Death of Jurkat Cells Requires Caspase 8-Induced, ATP-Dependent Cross-Talk between Fas and the Purinergic Receptor P2X(7) J. Cell Physiol. 2013;228:485–493. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q., Wang L., Feng Y.-H., Li X., Zeng R., Gorodeski G.I. P2X7 Receptor-Mediated Apoptosis of Human Cervical Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1349–C1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00256.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Porter A.G., Jänicke R.U. Emerging Roles of Caspase-3 in Apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sunilkumar D., Drishya G., Chandrasekharan A., Shaji S.K., Bose C., Jossart J., Perry J.J.P., Mishra N., Kumar G.B., Nair B.G. Oxyresveratrol Drives Caspase-Independent Apoptosis-like Cell Death in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells through the Induction of ROS. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;173:113724. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]