Introduction

Oropharynx squamous cell cancer (OPSCC) is increasing in incidence in the United States (U.S.) [1] and worldwide [2]. In light of these epidemiologic trends and the significant long-term morbidity and mortality of HPV-related OPSCC (HPV-OPSCC), there is interest in screening [2–4]. Screening for oncogenic oral HPV, the precursor for HPV-OPSCC [5], poses an intriguing possibility as there is growing literature that persistent oral HPV infection is a surrogate for microscopic HPV-OPSCC [6]. In cervical cancer, another HPV-related malignancy that has been studied for longer and has served as a paradigm for other HPV-related cancers, the presence of any oncogenic cervical HPV type is currently used for screening [7].

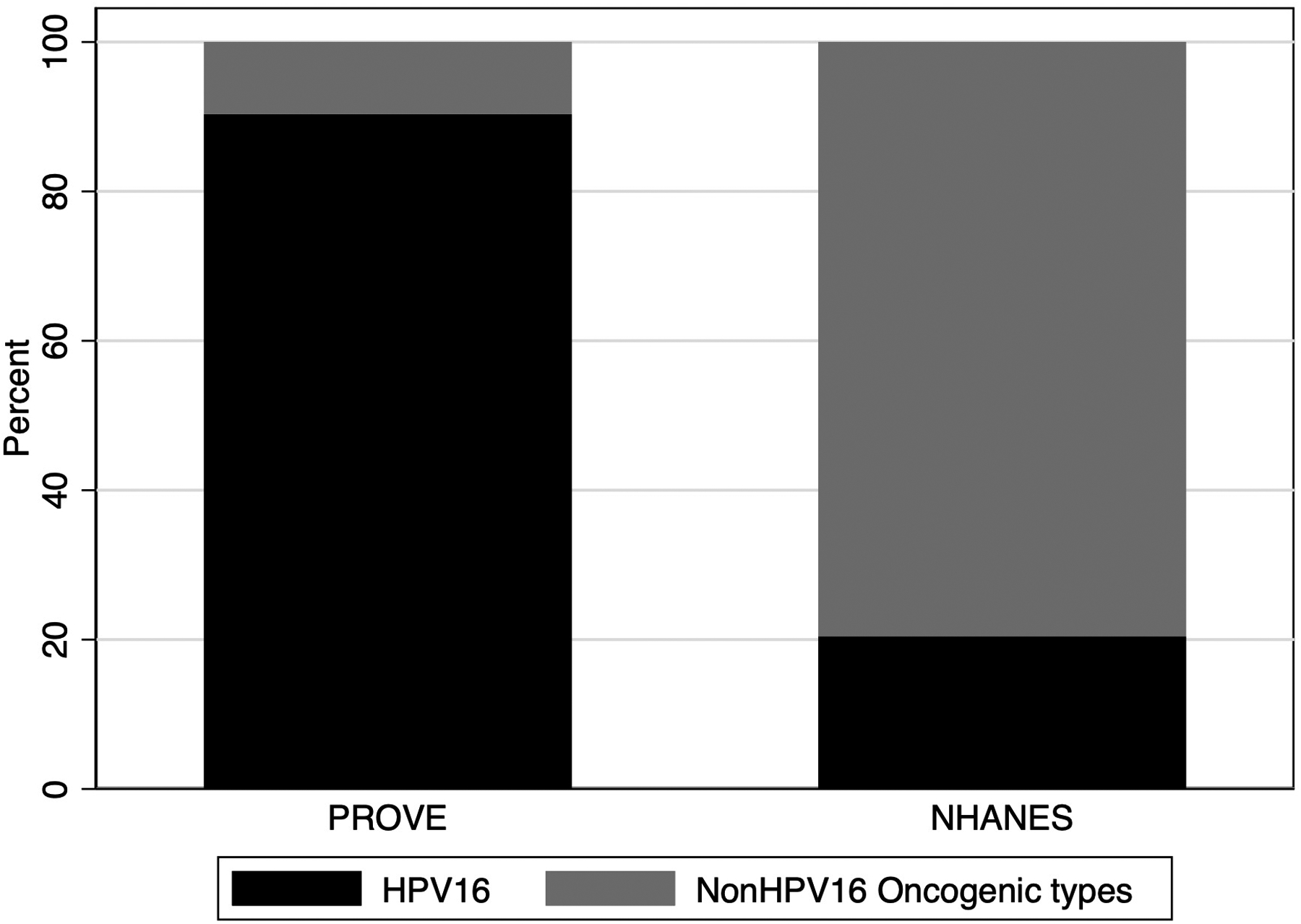

HPV16 causes 90–97% of HPV-OPSCC [2]. Current HPV-OPSCC screening studies [8,9] test for multiple oncogenic oral HPV types and provide a result of the presence of any oncogenic type, consistent with cervical HPV testing.

Seeing as HPV16 is the predominant type in HPV-related OPSCC, we examined whether non HPV16 oncogenic types are relevant in a screening scenario by comparing the HPV type distribution in tumors of people with HPV-related OPSCC to that observed in oral rinse samples in healthy individuals without cancer.

Methods

Data for this analysis came from two study populations; a general U.S. population National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and a cohort of HPV-related OPSCC cases Papillomavirus Role in Cancer Viral Etiology (PROVE).

NHANES Population

This study included individuals 20–69 years of age who participated in NHANES 2009–2016. Participants with HPV oral rinse data (n=18,526) who were positive for any oncogenic HPV type were included (n=779). Written consent was obtained from participants and NHANES was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics institutional review board (IRB).

PROVE Population

Participants with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas were enrolled 2013–2018 in an IRB- approved multicenter, prospective case-control study [10]. Eligibility for the present analysis was restricted to 145 HPV-OPSCCs.

HPV Testing

For this analysis detection of any oncogenic HPV was defined in both study datasets as any of the following types: 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82. Oncogenic HPV was measured in oral exfoliated cells in NHANES via PCR amplification using the PGYM09/11 primers and line-blot assay for 37 HPV types [11]. In PROVE, centralized tumor testing for HPV16 E6/E7 RNA situ hybridization (ISH, RNAscope®, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA) and p16 immunohistochemistry (MTM Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany) was performed first. In cases that were p16-positive but HPV16 RNA ISH-negative, additional testing was done using a E6/E7 RNA ISH probe (RNAscope, Advanced Cell Diagnostics) that included 18 high-risk HPV types (listed above) to identify nonHPV16 oncogenic types (i.e. negative for HPV16 RNA ISH and positive for HPV HR probe E6/E7 RNA ISH).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report proportions for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Characteristics were compared in HPV-OPSCC cases (from PROVE) and healthy people with oncogenic oral HPV DNA detected in the general U.S. population (from NHANES) using Pearson’s chi-square tests and 2-sample student’s t-tests for categorical and continuous variables respectively. Analysis was performed with Stata/IC version 15.1 for Windows.

Results

Among healthy individuals with detectable oncogenic oral HPV infection in NHANES, HPV16 was the most common oncogenic type detected (present in 20.4% (n=159) of those with an oncogenic HPV infection). This included 17.3% with only HPV16 and 3.1% with multiple oncogenic HPV types including HPV16. The next most common oncogenic HPV infections were HPV66 (14.0% of infections), HPV59 (10.4%) and HPV53, HPV51 and HPV35 (7–9% each).

The type distribution of oncogenic oral infections among healthy individuals was significantly different than those detected in tumors of HPV-OPSCC (Figure 1; p<0.001). While 20.4% were HPV16-positive in NHANES, 90.3% of HPV-OPSCC were HPV16-positive. This highlights that while most oncogenic oral HPV infections among healthy people are nonHPV16 oncogenic types, the converse is true in cancers where the overwhelming majority of oncogenic infections are HPV16.

Figure 1.

Proportion of oncogenic oral HPV infections that are HPV16 versus other non-HPV16 oncogenic types among OPSCC cancer patients (PROVE study) and the general US populations ages 18–69 (NHANES) Databases. Non-HPV16 oncogenic types included 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82.

Next, we compared characteristics of healthy individuals with oral HPV16 infection to those with HPV16-positive OPSCC. Healthy individuals were more likely to be younger, non-white, and to report current alcohol and tobacco use (each p<0.001). Lifetime number of vaginal, oral and any sex partners were similar for both groups.

Discussion

Although HPV16 is the most common oncogenic oral HPV infection among healthy individuals, there is no predominant type. In contrast, in the relevant cancer, HPV16 is the predominant type, responsible for the overwhelming majority of cancers in this study and in the literature [12–14]. This suggests that while many oncogenic HPV types are detected in the general population, HPV16 has the most relevance for screening, as most nonHPV16 oncogenic infections do not progress to cancer.

Testing for all oncogenic types would be inappropriate in an oropharyngeal screening scenario for multiple reasons. First, nonHPV16 oncogenic infections represent the majority of oncogenic oral infections (77.6%) in healthy people but are responsible for few (<10%) HPV-OPSCCs. HPV16 appears to be more persistent than other nonHPV16 oral infections [15]. Secondly, in a screening scenario, identification of any oncogenic type would necessitate a second step (increasing cost) to specify the HPV type to avoid overestimating risk in those identified by the combined probe. Third, the psychological harm introduced by screening individuals having low likelihood of developing cancer (nonHPV16 oncogenic infections) needs contemplation. Lastly, one of the purposes of a screening test is to enrich for an at-risk population; this analysis suggests HPV16 infection may be the ideal way of doing this, whether by testing orally, plasma or other means.

This analysis also informs whether the characteristics of healthy individuals with oral HPV16 are similar to those with HPV16-positive OPSCC, as risk factors for both are expected to overlap. While the sexual behaviors are similar, they have some distinct phenotypic differences in tobacco and alcohol use. Understanding what risk factors influence the shift from precursor oral HPV16 to cancer is of importance and may permit targeted oral HPV16 screening in specific populations.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics among patients diagnosed with HPV16 positive-oropharynx cancer (PROVE study) and healthy individuals with detectable oral HPV16 DNA (NHANES). IQR = Interquartile range.

| Patient Characteristics | HPV16-OPC n = 131 |

Oral HPV16 in healthy individuals n = 159 |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age (in years): | < 0.001 | ||||

| 18 – 29 | 1 | 0.8 | 25 | 15.7 | |

| 30 – 39 | 3 | 2.3 | 30 | 18.9 | |

| 40 – 49 | 25 | 19.1 | 34 | 21.4 | |

| 50 – 59 | 60 | 45.8 | 38 | 23.9 | |

| 60 – 69 | 42 | 32.1 | 32 | 20.1 | |

| Sex | 0.99 | ||||

| Male | 112 | 85.5 | 136 | 85.5 | |

| Female | 19 | 14.5 | 23 | 14.5 | |

| Race and Ethnicity | < 0.001 | ||||

| White non-Hispanic | 116 | 88.5 | 83 | 52.2 | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 8 | 6.1 | 35 | 22.0 | |

| Hispanic any race | 4 | 3.1 | 31 | 19.5 | |

| Other | 3 | 2.3 | 10 | 6.3 | |

| Cigarette Use | (n = 157) | < 0.001 | |||

| Never | 62 | 47.3 | 59 | 37.6 | |

| Current | 9 | 6.9 | 66 | 42.0 | |

| Former | 60 | 45.8 | 32 | 20.4 | |

| Alcohol Use | (n = 111) | (n = 159) | < 0.001 | ||

| Never | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Current | 57 | 51.4 | 121 | 76.1 | |

| Former | 52 | 46.8 | 36 | 22.6 | |

| Ever Illegal Drug Use | (n = 130) | (n = 145) | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 25 | 19.2 | 95 | 65.5 | |

| Yes | 105 | 80.8 | 50 | 34.5 | |

| Lifetime Sex Partners | (n = 144) | 0.06 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 20 (8 – 45) | 15 (6 – 35) | |||

| Lifetime Oral Sex Partners | (n = 112) | 0.17 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (4 – 25) | 8.5 (3 – 25.5) | |||

| Lifetime Vaginal Sex Partners | (n = 125) | (n = 109) | 0.1 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 20 (8 – 35) | 15 (6 – 30) | |||

Funding Acknowledgement

This work was made possible by support from National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [P50DE019032, R35DE026631].

Role of the funding source

Funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this paper.

References

- [1].Fakhry C, Krapcho M, Eisele DW, D’Souza G. Head and neck squamous cell cancers in the United States are rare and the risk now is higher among white individuals compared with black individuals. Cancer. 2018. 15;124(10):2125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2015. October 10;33(29):3235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].D’Souza G, McNeel TS, Fakhry C. Understanding personal risk of oropharyngeal cancer: risk-groups for oncogenic oral HPV infection and oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2017. December 1;28(12):3065–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].D’Souza G, Clemens G, Troy T, Castillo RG, Struijk L, Waterboer T, et al. Evaluating the Utility and Prevalence of HPV Biomarkers in Oral Rinses and Serology for HPV-related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. 2019;12(10):689–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Agalliu I, Gapstur S, Chen Z, Wang T, Anderson RL, Teras L, et al. Associations of Oral α-, β-, and γ-Human Papillomavirus Types With Risk of Incident Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016. May 1;2(5):599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, Xiao W, Jiang B, Agrawal A, et al. Association of Oral Human Papillomavirus DNA Persistence With Cancer Progression After Primary Treatment for Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019. July 1;5(7):985–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schiffman M, Kinney WK, Cheung LC, Gage JC, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, et al. Relative Performance of HPV and Cytology Components of Cotesting in Cervical Screening. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2017. November 14 [cited 2020 Jul 5]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6279277/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Men and Women Offering Understanding of Throat HPV - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 19]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03644563

- [9].MD Anderson Cancer Center. HOUSTON HPV Trial [Internet]. MD Anderson Cancer Center. [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/prevention-screening/manage-your-risk/hpv/houston-hpv-trial.html [Google Scholar]

- [10].D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, van Zante A, Wentz A, Kluz N, et al. Differences in the Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancers by Sex, Race, Anatomic Tumor Site, and HPV Detection Method. JAMA Oncol. 2017. February 1;3(2):169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].NHANES. NHANES 2013–2014: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) - Oral Rinse Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 13]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/ORHPV_H.htm

- [12].Goodman MT, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, Steinau M, Hernandez BY, Lynch CF, et al. Human Papillomavirus Genotype and Oropharynx Cancer Survival in the United States. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990 [Internet]. 2015. December [cited 2020 Jul 5];51(18):2759–67. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4666760/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mazul AL, Rodriguez-Ormaza N, Taylor JM, Desai DD, Brennan P, Anantharaman D, et al. Prognostic significance of non-HPV16 genotypes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol [Internet]. 2016. October [cited 2020 Jul 5];61:98–103. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5072454/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bratman SV, Bruce JP, O’Sullivan B, Pugh TJ, Xu W, Yip KW, et al. Human Papillomavirus Genotype Association With Survival in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016. June 1;2(6):823–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].M D’Souza G, Clemens G, Strickler HD, Wiley DJ, Troy T, Struijk L, et al. Long term persistence of oral HPV over 7 years of follow-up. JNCI Cancer Spectr [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 19]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jncics/article/doi/10.1093/jncics/pkaa047/5851842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]