Keywords: apoptosis, functional recovery, inflammatory response, long non-coding RNA, neuroprotection, NF-κB signaling pathway, RNA sequencing, spinal cord injury

Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious traumatic event to the central nervous system. Studies show that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play an important role in regulating the inflammatory response in the acute stage of SCI. Here, we investigated a new lncRNA related to spinal cord injury and acute inflammation. We analyzed the expression profile of lncRNAs after SCI, and explored the role of lncRNA Airsci (acute inflammatory response in SCI) on recovery following acute SCI. The rats were divided into the control group, SCI group, and SCI + lncRNA Airsci-siRNA group. The expression of inflammatory factors, including nuclear factor kappa B [NF-κB (p65)], NF-κB inhibitor IκBα and phosphorylated IκBα (p-IκBα), and the p-IκBα/IκBα ratio were examined 1–28 days after SCI in rats by western blot assay. The differential lncRNA expression profile after SCI was assessed by RNA sequencing. The differentially expressed lncRNAs were analyzed by bioinformatics technology. The differentially expressed lncRNA Airsci, which is involved in NF-κB signaling and associated with the acute inflammatory response, was verified by quantitative real-time PCR. Interleukin (IL-1β), IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) at 3 days after SCI were measured by western blot assay and quantitative real-time PCR. The histopathology of the spinal cord was evaluated by hematoxylin-eosin and Nissl staining. Motor function was assessed with the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan Locomotor Rating Scale. Numerous differentially expressed lncRNAs were detected after SCI, including 151 that were upregulated and 186 that were downregulated in the SCI 3 d group compared with the control group. LncRNA Airsci was the most significantly expressed among the five lncRNAs involved in the NF-κB signaling pathway. LncRNA Airsci-siRNA reduced the inflammatory response by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, alleviated spinal cord tissue injury, and promoted the recovery of motor function in SCI rats. These findings show that numerous lncRNAs are differentially expressed following SCI, and that inhibiting lncRNA Airsci reduces the inflammatory response through the NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby promoting functional recovery. All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jining Medical University (approval No. JNMC-2020-DW-RM-003) on January 18, 2020.

Chinese Library Classification No. R459.9; R364; R741

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) can lead to severe dysfunction of the limbs below the damaged segment, which not only affects the physical and mental health and quality of life of patients, but also imparts a huge economic burden on families and society (Kumar et al., 2018; Jung et al., 2019). The pathogenesis of SCI is complex, involving two stages of primary and secondary injury (Cao and Krause, 2020). After the occurrence of primary injuries such as fracture and compression, a series of secondary injuries such as inflammation, hypoxia, neuronal necrosis and apoptosis, and local microenvironmental changes further aggravate the SCI, resulting in severe loss of sensory and motor functions (Dai et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019b; Lv et al., 2019). At present, clinical therapeutics for SCI are limited and the pathogenesis of SCI still needs to be further studied.

It has been shown that the inflammatory response plays a key role in the pathogenesis of SCI (do Espírito Santo et al., 2019; He et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2020). Dysregulation of the inflammatory response after SCI causes a cascade effect, inducing apoptosis, edema, oxidative stress, and other reactions that aggravate tissue damage (Gao et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019). Early anti-inflammatory treatment can improve the clinical prognosis of patients with SCI (Gensel and Zhang, 2015). It has also been found that stem cell transplantation in the acute inflammatory phase can provide better functional recovery (Nishimura et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2017). Therefore, an in-depth study of the molecular mechanisms of SCI, including the dysregulation of the inflammatory response, may provide new molecular targets for the diagnosis and treatment of SCI.

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) is a type of RNA with a transcript length of over 200 nt and no protein-coding function (Rui et al., 2018). LncRNAs are widely expressed in organisms and have important regulatory functions (McDonel and Guttman, 2019; Qian et al., 2019). The main functions of lncRNAs include participating with competitive endogenous RNAs, interacting with proteins, regulating mRNA shearing, chromatin and histone remodeling, and transcriptional regulation (Shi et al., 2018). Preliminary studies show that lncRNAs play a critical role in the regulation of the molecular mechanisms involved in the acute phase of inflammatory dysregulation in SCI (Shao et al., 2020). LncRNA LOC685699-OT1 is a new transcript of gene LOC685699 (ENSRNOG00000043358), located on chromosome X:23419209–23467865. No studies on lncRNA LOC685699-OT1 in SCI have been found to date. Therefore, we named this lncRNA Airsci (acute inflammatory response in SCI) according to the rules of the Hugo Gene Naming Committee (HGNG) naming guidelines. Here, we found that lncRNA Airsci had the most significantly differential expression after SCI in rats, and its expression was significantly up-regulated during the acute inflammatory phase. Hence, exploring the molecular functions of lncRNA Airsci in SCI may provide new therapeutic targets and intervention strategies for treatment and rehabilitation following SCI.

Materials and Methods

Animals

A total of 105 healthy and specific pathogen-free adult (6–7-week-old) male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, weighing 250–280 g, were purchased from Jinan PengYue Experimental Animal Breeding Co., Ltd (Jinan, Shandong Province, China). The rats were kept at 25 ± 0.5°C in the SPF Experimental Animal Center of Jining Medical University. The light/dark cycle was altered for 12 hours. To examine the regulatory function of lncRNA Airsci in SCI rats, we divided the rats into the control group, SCI group, and SCI + lncRNA Airsci-siRNA group. Control group: only laminectomy, no SCI; SCI group: no intervention after SCI; SCI + lncRNA Airsci-siRNA group: The pLKO.1-sh Airsci small interfering RNA gene silencing plasmid was constructed. After transformation and identification, the plasmid was amplified using the plasmid extraction kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The plasmid was packaged with lentivirus and transfected in 293T cells according to 750 mL OPTI medium + 1 μg pMD2.G (envelope plasmid) + 2 μg pCMV-r8.74 (packaging plasmid) + 3 μg pLKO.1-sh Airsci to collect the lentivirus solution (Genechem, Shanghai, China). The filtered and purified lentivirus solution (0.5 mL) was injected into the SCI site to inhibit the expression of lncRNA Airsci. All procedures involving animals concurred with the Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines, and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jining Medical University (approval No. JNMC-2020-DW-RM-003) on January 18, 2020.

Establishment of the rat SCI model

The SCI model was established using the modified Allen technique (Lu et al., 2016). Pentobarbital sodium (Germany, Solarbio) was used for intraperitoneal injection anesthesia at a dose of 65 mg/kg. After anesthesia, the skin was prepared and disinfected in the back operation area. A 2–3 cm skin incision was made to separate the fascia and muscle, exposing the spinous process and lamina of T9–11. The ligaments and muscles on both sides of the T9–10 spinous process were detached to expose the T9–10 spinous process and transverse process, and the T9–10 spinous process and lamina were removed to expose the spinal cord fully. Using a spinal cord strike machine, a small 15 g blunt metal stick was allowed to fall freely from a height of 30 mm to produce blunt spinal cord contusion. After successful modeling, the wound was sewn up layer by layer. The postoperative manifestations of the rats were paralysis of the lower limbs and bladder distension. The rats were given bladder massage once in the morning and once in the evening for artificial urination.

Sample collection

Rats were sacrificed with 25% CO2 asphyxiation on days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 and 28 after SCI. Cardiac perfusion was performed using 10% formaldehyde solution for fixation. The surrounding segmental lamina were removed to fully expose the injured spinal cord tissues. The lesioned spinal cord tissues were cut 6 mm from the top to the bottom of the lesion site, and the tissue was preserved in liquid nitrogen for subsequent western blot assay, qPCR, and RNA-sequencing.

Western blot assay

Three days after SCI, the T9–11 spinal cord tissues were dissected out and homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured, and electrophoreses and membrane transfer were carried out. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB (p65), 1:500, Cat# ab16502, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-phosphorylated NF-κB inhibitor (p-IκBα, 1:1000, Cat# ab109300, Abcam), anti-IκBα (1:1000, Cat# ab109300, Abcam), anti-interleukin (IL-1β, 1:500, Cat# ab200478, Abcam), anti-IL-6 (1:500, Cat# ab9324, Abcam), anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α, 1:1000, Cat# ab109322, Abcam), anti-β-actin (1:1000, Cat# ab8226, Abcam). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:2000, Cat# ab6721 and ab6789, Abcam) at room temperature for 2 hours. Images were obtained by continuous exposures with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) imaging system (Tanon Imager, Shanghai, China). The final results were semi-quantitatively analyzed relative to the optical density of β-actin.

RNA-sequencing

From the western blot results, we found that 3 days after SCI was the critical time point during the acute inflammatory response period (Figure 1). Therefore, rats were divided into the control group and SCI 3d group for RNA-sequencing. After pentobarbital sodium anesthesia, spinal cord tissues of 3 mm length at each end of the head and tail of the rats were excised (the same parts were taken from the control group) with the injury point as the center, and total RNA was extracted with the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The RNA samples were tested, and then, a specific library was constructed after removing ribosomal RNA. The library was initially quantified by Qubit 2.0 (Shanghai, China) and diluted to 1.5 ng/μL. Then, the insert size (length of the sequence between the pair adapters) was analyzed on an Agilent 2100 (Shanghai, China). Once the insert size was satisfactory, the effective concentration of the library (greater than 3 nM) was accurately quantified by qRT-PCR to ensure library quality. Then, Illumina PE150 sequencing was conducted after pooling of the library according to the coverage required (sequencing was conducted by Shanghai Jikai Gene Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

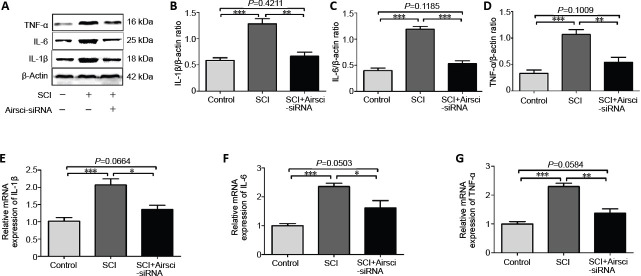

Figure 1.

NF-κB signaling pathway expression before and after SCI.

(A) Western blot assay was performed to analyze changes in expression of the inflammatory proteins NF-κB (p65), p-IκBα and IκBα, which are associated with the NF-κB signaling pathway, at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days after SCI. (B–E) The optical density analysis of NF-κB(p65), p-IκBα, IκBα protein, and the p-IκBα/IκBα ratio at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days after SCI. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. IκBα: NF-κB inhibitor; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; p-IκBα: phosphorylated IκBα; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Screening of lncRNAs by bioinformatics technology

We used RNA-sequencing to detect changes in lncRNA expression in the spinal cord tissues of rats in the control group and the SCI 3d group, and obtained the expression profile heat map of lncRNAs. Then, bioinformatics technology was used to screen the differential lncRNAs in the SCI 3d group that were related to the inflammatory response. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.kegg.jp/) is a database for the systematic analysis of relationships, gene function and gene information between genes and their encoded products. To identify lncRNAs associated with acute inflammation, we first screened lncRNAs according to the set fold change (over 10 times) and the significance level of expression difference (< 0.05) between the SCI 3 days and control groups. Next, target gene prediction and KEGG function enrichment analysis were performed. Finally, the lincRNA Airsci, which is involved in the NF-κB signaling pathway and associated with the acute inflammatory response, was selected for further analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to measure the expression levels of related genes in each group 3 days after SCI. Total RNA in tissues (40–50 mg) was extracted by the Trizol method (Invitrogen). The purity and quantity of RNA were determined with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (SYNERGY H1, BioTek, USA) and then diluted with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). cDNA was then synthesized according to the instructions in the TaKaRa RNA PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan). qRT-PCR parameters were as follows: 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles (amplification) of 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation), 60°C for 40 seconds (annealing), and 72°C for 20 seconds (extension). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene, and the relative quantification of gene expression levels was performed using the 2–ΔΔCt method. The sequences of all primers used for the qRT-PCR experiments are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR primers

| Primers | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| LOC685699-OT1 | F: TCG GAC TGT GGG AGG CTT ATT ACC | 24 |

| R: GGT GAA ATG GTC CAG GTC GAG TTG | 24 | |

| AABR07015057.1-OT11 | F: GCC GCC ACA AGC CAG TTA TCC | 21 |

| R: TAT CCG CAG CAG GTC TCC AAG G | 22 | |

| LINC5298 | F: ACT TCT CTA AGG CCC TCA CCA G | 22 |

| R: AAG TCC ACC CAC AGG CAG AA | 20 | |

| AABR07000398.1-OT18 | F: CTT GGC TGC TCG TCG GTG TTG | 21 |

| R: GCG TGA TCC CTC CTC GTA CTC G | 22 | |

| AABR07055878.1-OT1 | F: TCA GAA ACC AGG TGC CCA CTT AAC | 24 |

| R: TCG ACC TCT CTG GCT GGA TGA AG | 23 | |

| IL-1β | F: CCT TGT GCA AGT GTC TGA AGC | 21 |

| R: CCC AAG TCA AGG GCT TGG AA | 20 | |

| IL-6 | F: GGC CCT TGC TTT CTC TTC G | 19 |

| R: ATA ATA AAG TTT TGA TTA TGT | 21 | |

| TNF-α | F: CTC CAG CTG GAA GAC TCC TCC CAG | 24 |

| R: CCC GAC TAC GTG CTC CTC ACC | 21 | |

| GADPH | F: AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG | 21 |

| R: TGT AGA CCA TGT AGT TGA GGT CA | 23 |

F: Forward; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IL: Interleukin; R: reverse; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α.

Hematoxylin-eosin and Nissl staining

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and Nissl staining were used to evaluate the histopathology of the spinal cord in each group at 3 days after SCI. The collected tissues were paraffin-embedded, sectioned into 10 μm sections, and then HE and Nissl staining were performed. HE staining: The sections were stained with hematoxylin for 1 minute, and washed with water. Then, they were immersed in 1% hydrochloric acid/ethanol for 5 seconds and rinsed with water. Sections were then treated with ammonia water for 5 minutes and rinsed with water. Eosin staining was conducted for 1 min and rinsed with water. Sections were then dehydrated sequentially with 80%, 95% and anhydrous ethanol for 10 seconds each. Nissl: The sections were immersed overnight in an equal volume of anhydrous ethanol and chloroform solution. On the next day, they were immersed in anhydrous ethanol, 95% ethanol, and distilled water. The sections were then placed in 0.1% methylphenol solution at 40°C for 10 minutes and washed quickly with distilled water. We observed the tissue morphology of HE staining sections with an optical microscope (OLYMPUS, Jinan, China) and measured the proportional spinal cord tissue lesion size with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, USA). We observed the neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and performed count analysis with the optical microscope (five animals were included; counting was performed at 400× magnification; results were expressed as averages).

Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan Locomotor Rating Scale assessment

The motor function of rat hind limbs was measured by the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan Locomotor Rating Scale (BBB) score (All et al., 2020) at different time points (0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 days) after SCI. BBB scores ranged from 0 to 21 points. The minimum number of points (0) indicates complete paralysis and the maximum number of points (21) represents normal function. Three uninformed researchers assessed the motor function of rats. As the score increased, the motor function improved.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and expressed as the mean ± SD. Western blot, qPCR, HE and Nissl staining differences among multiple groups were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test. BBB scores were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The NF-κB signaling pathway is activated after SCI in rats

Western blot results showed that NF-κB (p65) and p-IκBα protein expression increased initially and then decreased between 1 and 28 days after SCI (Figure 1). The p-IκBα/IκBα ratio initially increased and reached a peak at 3 days after SCI, and thereafter decreased (Figure 1).

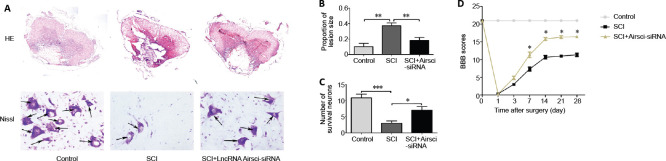

lncRNAs are differentially expressed after SCI in rats

RNA-sequencing results showed that lncRNAs were differentially expressed at 3 days after SCI (Figure 2A). Compared with the control group, 151 lncRNAs were upregulated and 186 lncRNAs were downregulated in the SCI 3d group (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

LncRNA expression profile after SCI (RNA-sequencing).

(A) Heat map of differentially expressed lncRNAs in the SCI 3 d group compared with the control group. X-axis shows the control samples and SCI 3 d samples; Y-axis shows the differentially expressed lncRNAs (P < 0.05). Expression increases are shown as change from blue to red. (B) Differential lncRNA volcano map. X-axis represents the fold change of gene expression between different samples or comparison combinations (log2 FoldChange); Y-axis indicates the significance level of the expression difference. The upregulated lncRNAs are represented by red dots, the down-regulated lncRNAs are represented by green dots, and the blue dots are lncRNAs that have not changed significantly. The number of differentially expressed lncRNAs varied, and compared with the control group, 151 lncRNAs were upregulated and 186 lncRNAs were downregulated in the SCI 3 d group. lncRNA: Long non-coding RNA; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Screening of lncRNA Airsci and examining its effect on the NF-κB signaling pathway

KEGG functional enrichment analysis of lncRNA expression profiles at 3 days after SCI revealed a variety of signaling pathways, including the NF-κB signaling pathway (Figure 3A). Bioinformatics was used to screen for lncRNAs involved in the NF-κB signaling pathway and associated with the acute inflammatory response. The screen identified the following five lncRNAs: LOC685699-OT1 (Airsci), AABR07015057.1-OT11, LINC5298, AABR07000398.1-OT18 and AABR07055878.1-OT1. All five lncRNAs were verified by qRT-PCR, and the differences were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05), consistent with the results of RNA-sequencing. Among these, the expression of lncRNA Airsci increased significantly after SCI (Figure 3B). Accordingly, we divided the rats into the control group, SCI group and SCI + lncRNA Airsci-siRNA group, and western blot was used to detect the expression levels of NF-κB (p65), phospho-IκBα and IκBα (Figure 3C). Inhibition of lncRNA Airsci significantly reduced the protein expression levels of NF-κB (p65) and p-IκBα, and reduced the p-IκBα/IκBα ratio (Figure 3D–G).

Figure 3.

Screening of lncRNA Airsci 3 days after SCI and regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

(A) KEGG functional enrichment analysis of lncRNA expression profiles revealed the involvement of multiple signaling pathways. Y-axis represents differential signaling pathways; X-axis represents the proportion of significantly differentially expressed genes in the corresponding signaling pathway to all genes in the signaling pathway. The size of the circle represents the number of genes enriched in the corresponding signaling pathway; the larger the circle, the more genes enriched in the pathway. The color represents the significance of enrichment—the closer to red, the more significant. (B) The five lncRNAs involved in the NF-κB signaling pathway and associated with the acute inflammatory response were validated by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) Western blot was used to detect the NF-κB signaling pathway-related inflammatory proteins NF-κB (p65), p-IκBα and IκBα in the control group, SCI group and the SCI + lncRNA Airsci-siRNA group. (D–G) The optical density analysis of NF-κB(p65), p-IκBα, IκBα protein and the p-IκBα/IκBα ratio. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Airsci: Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord injury; IκBα: NF-κB inhibitor; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; p-IκBα: phosphorylated IκBα; SCI: spinal cord injury.

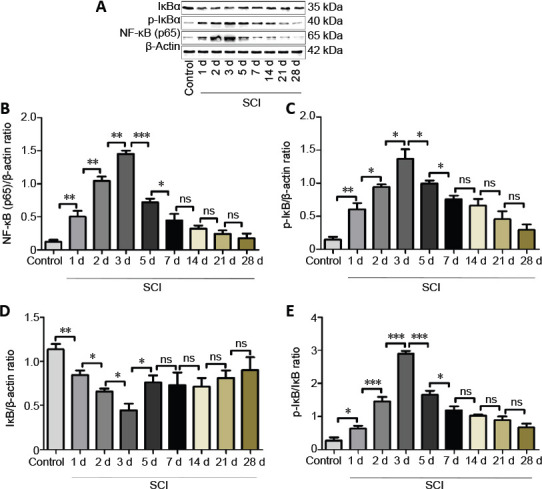

Inhibiting lncRNA Airsci reduces the inflammatory response after SCI in rats

Western blot and qRT-PCR results showed that the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were dramatically increased in the SCI group at 3 days after SCI compared with the control group. Inhibition of lncRNA Airsci significantly reduced the protein and mRNA expression levels of the inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LncRNA Airsci regulates the inflammatory response at 3 days after SCI.

(A–D) The protein (A; western blot) and mRNA (E–G; qRT-PCR) levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) in the control, SCI and SCI + Airsci-siRNA groups. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Airsci: Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord injury; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; IL-6: interleukin-6; IκBα: NF-κB inhibitor; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; p-IκBα: phosphorylated IκBα; SCI: spinal cord injury.

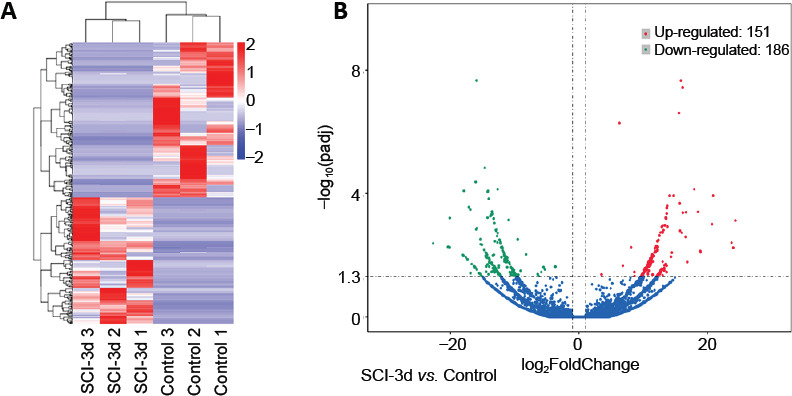

Inhibiting lncRNA Airsci ameliorates histopathological changes in the spinal cord and promotes the recovery of motor function in rats

HE staining was performed to assess the histopathology of the spinal cord tissues 3 days after SCI (Figure 5A). The proportional lesion size was larger in the SCI group compared with the control group. In comparison, the proportional lesion size was smaller in the Airsci-siRNA group than in the SCI group (Figure 5B). Nissl staining was used for counting spinal cord motor neurons and for detecting neuronal injury (Figure 5A). The number of Nissl-positive cells in the anterior horn of the spinal cord was less in the SCI group compared with the control group. Airsci-siRNA dramatically increased the number of Nissl-positive cells compared with the SCI group (Figure 5C). The BBB score was used to assess motor function after SCI (Figure 5D). The BBB score in the SCI group decreased significantly compared with the control group. Notably, the score was markedly higher in the Airsci-siRNA group than in the SCI group at 7 days after SCI.

Figure 5.

LncRNA Airsci regulates histopathological changes in spinal cord tissue and motor function in rats.

(A) The histopathology (hematoxylin-eosin staining, original magnification 50×) and neuronal death (Nissl staining, original magnification 400×) in spinal cord tissue in the control, SCI and SCI + Airsci-siRNA groups at 3 days after SCI. Arrows indicate healthy large-diameter Nissl-positive neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. (B) The proportional lesion size was measured with ImageJ software. Y-axis represents the ratio of the injured area to the total area of the spinal cord; X-axis represents the different groups. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test). **P < 0.01. (C) The quantitative analysis of motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, one-way analysis of variance and the least significant difference test). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (D) The recovery of motor function in SCI rats (BBB score; *P < 0.05, vs. control and SCI groups). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 6, Mann-Whitney U test). Airsci: Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord injury; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; SCI: spinal cord injury; siRNA: small interfering RNA.

Discussion

SCI is a serious traumatic event to the central nervous system (Kleene et al., 2019). The inflammatory response plays an important role in the pathophysiology of SCI and affects recovery and functional outcome (Lemmens et al., 2019; Şaker et al., 2019). Studies have shown that lncRNAs play an important role in regulating the inflammatory response in the acute stage of SCI (Zhou et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2019). Therefore, further study of the molecular mechanisms underpinning lncRNA function may provide new ideas and methods for the treatment of SCI.

In this study, our major findings are as follows: (1) The NF-κB signaling pathway is significantly activated after SCI, and the inflammatory response is significantly increased, with the most significant increase at 3 days after SCI; (2) The expression of lncRNA after SCI is significantly different and plays a pivotal role in the pathological mechanism of SCI; (3) LncRNA Airsci is involved in the regulation of the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway; (4) Inhibiting lncRNA Airsci reduces the inflammatory response, lessens the area of spinal cord tissue damage, reduces the death of neurons, and promotes the recovery of motor function.

Current studies demonstrate that lncRNAs are significantly differentially expressed after SCI, and play an important regulatory role in the process of tissue repair (Zhang et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019). For example, lncRNA MALAT1 inhibits autophagy and apoptosis of neurons and promotes SCI repair by regulating the Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (Liu et al., 2019). In vitro studies of PC12 cells show that lncRNA Mirt2 inhibits the p38MAPK signaling pathway by downregulating miRNA-429 and reducing apoptosis (Li et al., 2019a). Unfortunately, these studies on lncRNA in SCI are mainly focused on neuronal proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy, and few studies have been conducted on the regulatory function of lncRNAs in the acute phase of SCI (Ren et al., 2019).

Preliminary research has shown that lncRNA MALAT1 promotes the inflammatory response in the SCI acute phase by regulating miRNA-199b, demonstrating that lncRNA plays an important role in the regulation of the molecular mechanisms of the acute inflammatory response (Zhou et al., 2018). However, in-depth studies of the expression profile of lncRNAs in the SCI acute phase are lacking. Further study, including additional screening of lncRNAs, may clarify their important regulatory functions in the SCI acute inflammatory response, and may provide new ideas and methods for SCI treatment.

A modified Allen’s apparatus was used to produce the rat SCI model, and we assessed changes in NF-κB(p65), p-IκBα, IκBα and the p-IκBα/IκBα ratio at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days after SCI. We found that the NF-κB signaling pathway reached peak activation on the third day after SCI. We used RNA-sequencing to detect changes in lncRNA expression in spinal cord tissues after SCI, and found that different lincRNAs were expressed. Compared with the control group, 151 lincRNAs were upregulated and 186 lincRNAs were downregulated in the SCI 3d group. To identify lincRNAs involved in the NF-κB signaling pathway and associated with the acute inflammatory response, we screened the lncRNAs through bioinformatics analysis and then verified them by qRT-PCR. Among the five lncRNAs of interest, lncRNA Airsci was significantly upregulated during the SCI acute inflammatory phase. We hypothesized that exploring the role and mechanism of lncRNA Airsci in SCI may provide new therapeutic targets and intervention strategies for the treatment and rehabilitation of SCI. We found that inhibiting lncRNA Airsci expression suppressed the NF-κB signaling pathway, decreased the inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, and ameliorated spinal cord tissue damage and improved motor function. Therefore, we speculated that inhibiting the expression of lncRNA Airsci could reduce the inflammatory response through NF-κB signaling and promote functional recovery in SCI rats. However, the underlying mechanisms still need to be elucidated, and will be the focus of upcoming studies.

In summary, the pathological progression of SCI is closely related to the regulation of the inflammatory response, as well as the differential expression of lncRNAs (Ding et al., 2020). We screened lncRNAs by bioinformatics and verified candidates by qRT-PCR. LncRNA Airsci was significantly upregulated during the SCI acute inflammatory phase. Notably, inhibition of lncRNA Airsci reduced the inflammatory response through the NF-κB signaling pathway and promoted functional recovery. Therefore, we speculate that lncRNA Airsci mediates the inflammatory response after SCI in rats through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Our further studies will perform expression analysis on the brain and spinal cord by tissue hybridization to provide insight into the expression profile of Airsci in the CNS in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dong-Mei Shi from Department of the Key Laboratory of Fungi in the Jining First People’s Hospital, China for providing valuable technical assistance in this work.

Footnotes

C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editors: Li CH; L-Editors: Patel B, Li CH, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81801906; to KG) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (No. ZR2018PH024; to KG).

Institutional review board statement: All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jining Medical University (approval No. JNMC-2020-DW-RM-003) on January 18, 2020. All experimental procedures described here were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement: Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81801906; to KG) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (No. ZR2018PH024; to KG).

References

- 1.All AH, Al Nashash H, Mir H, Luo S, Liu X. Characterization of transection spinal cord injuries by monitoring somatosensory evoked potentials and motor behavior. Brain Res Bull. 2020;156:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao Y, Krause JS. Estimation of indirect costs based on employment and earnings changes after spinal cord injury: an observational study. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:908–913. doi: 10.1038/s41393-020-0447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng I, Park DY, Mayle RE, Githens M, Smith RL, Park HY, Hu SS, Alamin TF, Wood KB, Kharazi AI. Does timing of transplantation of neural stem cells following spinal cord injury affect outcomes in an animal model. J Spine Surg. 2017;3:567–571. doi: 10.21037/jss.2017.10.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai J, Yu GY, Sun HL, Zhu GT, Han GD, Jiang HT, Tang XM. MicroRNA-210 promotes spinal cord injury recovery by inhibiting inflammation via the JAK-STAT pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:6609–6615. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201810_16135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding L, Fu WJ, Di HY, Zhang XM, Lei YT, Chen KZ, Wang T, Wu HF. Expression of long non-coding RNAs in complete transection spinal cord injury: a transcriptomic analysis. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:1560–1567. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.274348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.do Espírito Santo CC, da Silva Fiorin F, Ilha J, Duarte MMMF, Duarte T, Santos ARS. Spinal cord injury by clip-compression induces anxiety and depression-like behaviours in female rats: The role of the inflammatory response. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;78:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao K, Zhang T, Wang F, Lv C. Therapeutic potential of Wnt-3a in neurological recovery after spinal cord injury. Eur Neurol. 2019;81(3-4):197–204. doi: 10.1159/000502004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gensel JC, Zhang B. Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2015;1619:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Z, Zang H, Zhu L, Huang K, Yi T, Zhang S, Cheng S. An anti-inflammatory peptide and brain-derived neurotrophic factor-modified hyaluronan-methylcellulose hydrogel promotes nerve regeneration in rats with spinal cord injury. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:721–732. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S187854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang LJ, Li G, Ding Y, Sun JH, Wu TT, Zhao W, Zeng YS. LINGO-1 deficiency promotes nerve regeneration through reduction of cell apoptosis, inflammation, and glial scar after spinal cord injury in mice. Exp Neurol. 2019;320:112965. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia H, Ma H, Li Z, Chen F, Fang B, Cao X, Chang Y, Qiang Z. Downregulation of LncRNA TUG1 inhibited TLR4 signaling pathway-mediated inflammatory damage after spinal cord ischemia reperfusion in rats via suppressing TRIL expression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78:268–282. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung JH, Lee HJ, Cho DY, Lim JE, Lee BS, Kwon SH, Kim HY, Lee SJ. Effects of combined upper limb robotic therapy in patients with tetraplegic spinal cord injury. Ann Rehabil Med. 2019;43:445–457. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleene R, Loers G, Jakovcevski I, Mishra B, Schachner M. Histone H1 improves regeneration after mouse spinal cord injury and changes shape and gene expression of cultured astrocytes. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2019;37:291–313. doi: 10.3233/RNN-190903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar R, Lim J, Mekary RA, Rattani A, Dewan MC, Sharif SY, Osorio-Fonseca E, Park KB. Traumatic spinal injury: global epidemiology and worldwide volume. World Neurosurg. 2018;113:e345–363. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemmens S, Nelissen S, Dooley D, Geurts N, Peters E, Hendrix S. Stress pathway modulation is detrimental or ineffective for functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2019:37. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Xu Y, Wang G, Chen X, Liang W, Ni H. Long non-coding RNA Mirt2 relieves lipopolysaccharide-induced injury in PC12 cells by suppressing miR-429. J Physiol Biochem. 2019a;75:403–413. doi: 10.1007/s13105-019-00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li JL, Liang YL, Wang YJ. Knockout of ALOX12 protects against spinal cord injury-mediated nerve injury by inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019b;516:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Yu G, Song G, Zhang Q. Green tea polyphenols protect PC12 cells against H2O2-induced damages by upregulating lncRNA MALAT1. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2019;33:2058738419872624. doi: 10.1177/2058738419872624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Lu GB, Niu FW, Zhang YC, Du L, Liang ZY, Gao Y, Yan TZ, Nie ZK, Gao K. Methylprednisolone promotes recovery of neurological function after spinal cord injury: association with Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1816–1823. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lv ZC, Cao XY, Guo YX, Zhang XD, Ding J, Geng J, Feng K, Niu H. Effects of MiR-146a on repair and inflammation in rats with spinal cord injury through the TLR/NF-κB signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:4558–4563. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201906_18031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonel P, Guttman M. Approaches for understanding the mechanisms of long noncoding RNA regulation of gene expression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11:a032151. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura S, Yasuda A, Iwai H, Takano M, Kobayashi Y, Nori S, Tsuji O, Fujiyoshi K, Ebise H, Toyama Y, Okano H, Nakamura M. Time-dependent changes in the microenvironment of injured spinal cord affects the therapeutic potential of neural stem cell transplantation for spinal cord injury. Mol Brain. 2013;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh JY, Hwang TY, Jang JH, Park JY, Ryu Y, Lee H, Park HJ. Muscovite nanoparticles mitigate neuropathic pain by modulating the inflammatory response and neuroglial activation in the spinal cord. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:2162–2168. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.282260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian X, Zhao J, Yeung PY, Zhang QC, Kwok CK. Revealing lncRNA structures and interactions by sequencing-based approaches. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44:33–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren XD, Wan CX, Niu YL. Overexpression of lncRNA TCTN2 protects neurons from apoptosis by enhancing cell autophagy in spinal cord injury. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9:1223–1231. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rui X, Xu Y, Jiang X, Ye W, Huang Y, Jiang J. Long non-coding RNA C5orf66-AS1 promotes cell proliferation in cervical cancer by targeting miR-637/RING1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1175. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Şaker D, Sencar L, Yılmaz DM, Polat S. Relationships between microRNA-20a and microRNA-125b expression and apoptosis and inflammation in experimental spinal cord injury. Neurol Res. 2019;41:991–1000. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2019.1652014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao M, Jin M, Xu S, Zheng C, Zhu W, Ma X, Lv F. Exosomes from Long Noncoding RNA-Gm37494-ADSCs Repair Spinal Cord Injury via Shifting Microglial M1/M2 Polarization. Inflammation. 2020;43:1536–1547. doi: 10.1007/s10753-020-01230-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Z, Pan B, Feng S. The emerging role of long non-coding RNA in spinal cord injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:2055–2061. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Zhang L, Ndong JC, Hettinghouse A, Sun G, Chen C, Zhang C, Liu R, Liu CJ. Progranulin deficiency exacerbates spinal cord injury by promoting neuroinflammation and cell apoptosis in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:238. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Wang W, Li N, Li P, Liu M, Pan J, Wang D, Li J, Xiong Y, Xia L. LncRNA DGCR5 suppresses neuronal apoptosis to improve acute spinal cord injury through targeting PRDM5. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:1992–2000. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1509622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou HJ, Wang LQ, Wang DB, Yu JB, Zhu Y, Xu QS, Zheng XJ, Zhan RY. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 contributes to inflammatory response of microglia following spinal cord injury via the modulation of a miR-199b/IKKβ/NF-κB signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;315:C52–C61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00278.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou HJ, Wang LQ, Wang DB, Yu JB, Zhu Y, Xu QS, Zheng XJ, Zhan RY. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 contributes to inflammatory response of microglia following spinal cord injury via the modulation of a miR-199b/IKKβ/NF-κB signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;315:C52–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00278.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]