Abstract

We present the case of a 23-year-old patient who developed a severe gastric ischemia after the ingestion of a single dose of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) orally. Emergency surgery confirmed extensive full thickness gastric necrosis, prompting a total gastrectomy. Histopathology showed kayexalate crystals in the gastric wall, suggesting SPS-related ischemic gastritis. After radical resection of the affected stomach, this young patient was able to fully recover. Although effective, the widespread use of SPS to treat hyperpotassemia remains a debated topic because of rare but serious adverse events like the forming of kayexalate crystal residues in the gastrointestinal tract. These crystal residues are mostly found in the large intestine and can lead to ulceration and necrosis. Physicians need to be aware of this rare but potentially devastating adverse effect of SPS ingestion.

INTRODUCTION

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) is a cation-exchange resin used in the treatment of hyperpotassemia. The drug was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1958, before the ‘Drug Efficacy Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act’ went into effect. Thus, at the time of approval, the use of SPS lacked support from well-designed drug safety and efficacy trials. Today, SPS is effectively used to treat mild hyperpotassemia [1]. Still, the use of SPS remains a debated topic [2, 3]. Current literature reports several cases of SPS-related gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers and necrosis, affecting primarily the large intestine [4–7].

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old, male medical student suffered from disease relapse 4 years after early T-cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia and allogenic stem cell transplantation (SCT). The patient received re-induction therapy, including local radiotherapy, systemic chemotherapy, nelarabine as well as triple intrathecal chemotherapy, and complete disease remission was achieved. After consolidation chemotherapy, the patient underwent his second allogenic SCT. Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine and methotrexate. On Day 5 post-transplantation, he developed mild oral mucositis. This was followed by headache and moderate abdominal discomfort by Day 10.

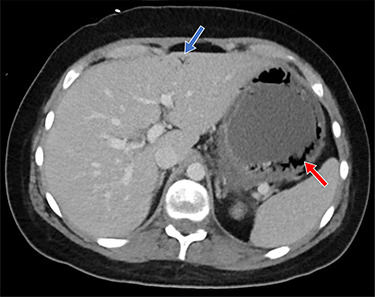

Clinical and laboratory examination revealed slightly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP, 71.1 mg/l [normal range < 10 mg/l]) and potassium (5.1 mmol/l [normal range 3.6–4.8 mmol/l]) levels. The cyclosporine dosage was reduced, causing initial improvement of symptoms. Because of recurrent hyperpotassemia of 5.5 mmol/l 12 days post-transplantation, the patient received 15 mg of SPS orally. The same day, the patient complained of progressive abdominal pain. His body temperature was 38.5°C, heart rate at 91 beats per minute, blood pressure at 126/80 mmHg, and peripheral oxygen saturation levels at 95% breathing ambient air. The abdomen was bloated without signs of peritonitis. White blood cell count was 1.03 × 109/l (normal range 3.50–10.00 × 109/l) and neutrophils 0.18 × 109/l (normal range 1.300–6.700 × 109/l). The CRP levels rose to 109 mg/l. Given the elevated CRP levels, combined with progressive abdominal discomfort and fever, a thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained. CT scan showed a thickened gastric wall with gastric pneumatosis (GP) accompanied by air in the hepatic portal vein system (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 .

Shown is air in the gastric wall (red arrow) and air in the hepatic portal venous system (blue arrow)

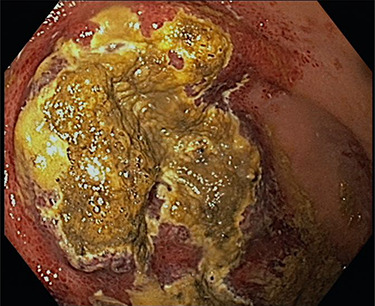

The decision was made to perform an upper GI endoscopy to evaluate the mucosa before potential surgery. Endoscopy revealed generalized mucosal erythema with intramucosal bleeding in the gastric fundus and corpus along the greater curvature of the stomach. Additionally, two massive areas of necrosis, measuring three and six centimeters in diameter, respectively, were found on the margin between fundus and body (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 .

Shown is a large necrotic area in the gastric fundus and corpus along the greater curvature

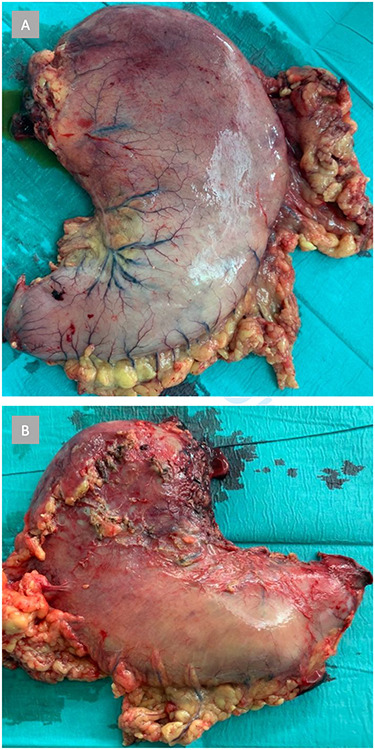

It was decided to perform an exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative findings confirmed a necrosis of the gastric wall, especially on the lateral aspect of the fundus and body. Because of the extent of the necrosis, a total gastrectomy with end-to-side esophago-jejunal stapler anastomosis was performed. After a short postoperative stay on the intensive care unit for pain-control, the patient was transferred back to the isolation ward where he recovered slowly under total parenteral nutrition and antibiotic therapy.

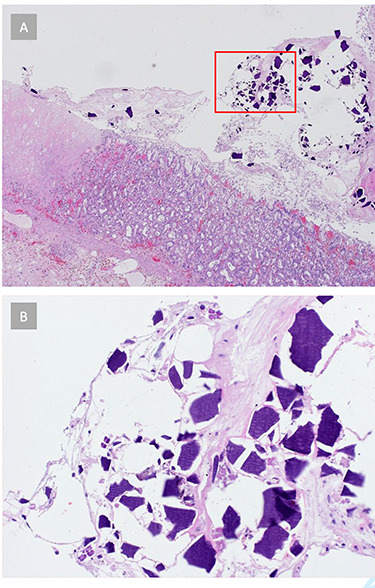

Histopathology showed a resected stomach with GP and circumscribed ischemic transmural necrosis, accompanied by purulent peritonitis (Fig. 3). Several light basophilic crystals in the necrotic gastric mucosa were detected and interpreted as kayexalate crystals (Fig. 4). There was no evidence of GvHD in the remaining gastric mucosa and no signs of a Helicobacter pylori infection. The resection margins were vital.

Figure 3 .

Shown is the resected stomach with extensive macroscopic signs of ischemic necrosis, primarily in the fundus and corpus. (A) Anterior view. (B) Posterior view

Figure 4 .

(A) Histopathology reveals signs of acute gastritis and ischemic tissue areas. Crystalline structures are found in the gastric tissue. (B) Gastric tissue crystals morphologically consistent with kayexalate crystals, suggesting SPS-related ischemic gastritis

On postoperative Day 7, an upper GI X-ray series showed a normal passage through the esophago-jejunostomy with no signs of leakage. Over the course of the further hospitalization, the patient fully recovered and was able to be discharged 30 days postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

Oral and GI mucositis are common toxic effects of chemotherapy and occur in many patients after SCT [8]. A common side effect of cyclosporine treatment is hyperpotassemia, caused by impaired renal potassium excretion [9]. Although the initial response to cyclosporine dose reduction and symptomatic therapy was satisfactory, a recurring hyperpotassemia was treated with SPS orally. The CT scan showed a GP combined with hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) as signs of possible necrosis. GP is an uncommon finding but associated with severe consequences such as necrosis of the mucosa or even the gastric wall and might result in peritonitis and sepsis with life-threatening complications for patients. GP is associated with significant comorbidity, surgical interventions and potential mortality [10]. Both GP and HPVG can be signs of GI tract necrosis secondary to GvHD. Acute GvHD occurs in up to 50% of patients after SCT and primarily affects the GI tract, liver and skin [11]. Up to 12% of GvHD cases involve the upper GI tract [12] but histopathology ruled out GvHD as the cause of pneumatosis in our case. Symptoms of GI tract infection and elevated liver enzyme and bilirubin levels can also be a sign of cytomegaly virus (CMV) infection, which occurs in up to 30% of patients after SCT [13]. However, in our patient, there were no signs of CMV infection in the blood and tissue samples.

The use of SPS has been associated with serious adverse GI events such as intestinal ulcers, thrombosis and ischemia [14]. A retrospective cohort study of 123,391 patients in 2012 found an incidence of colonic necrosis of 0.14% within 30 days of SPS prescription, as opposed to 0.07% in patients not prescribed SPS [15]. A systematic review from 2013 reported 58 cases of adverse events after ingestion with SPS, where the colon was with 76% the most common site of injury, and the stomach was involved in 3% of cases [14]. The histopathology of 62% of resected patient samples in that same study had shown transmural necrosis like in our case, and SPS crystals were found in 90% of affected GI segments, exposing the diagnosis. Such GI injuries are associated with high morbidity and mortality [14]. Thus, aggressive therapy is warranted in these cases. After radical resection of the affected stomach, our patient was able to fully recover and resume his studies to become a medical doctor. This is a rare case of isolated stomach necrosis related to SPS ingestion, and highlights the severity of consequences of a rare but potentially devastating adverse effect of SPS prescription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our patient, who was open-minded to publish his case. We wish him all the best for his recovery and that he will be an excellent medical doctor for his patients in the future. Furthermore, we thank our colleagues in radiology, especially Prof Daniel Boll, who immediately presented this case to us abdominal surgeons.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- 1. Mistry M, Shea A, Giguère P, Nguyen ML. Evaluation of sodium polystyrene sulfonate dosing strategies in the inpatient management of hyperkalemia. Ann Pharmacother 2016;50:455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kamel KS, Schreiber M. Asking the question again: are cation exchange resins effective for the treatment of hyperkalemia? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:4294–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: Are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:733–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oliveira AA, Pedro F, Craveiro N, Cruz AV, Almeida RS, Luís PP, et al. Rectal ulcer due to kayexalate deposition – an unusual case. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2018;64:680–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albeldawi M, Gaur V, Weber L. Kayexalate-induced colonic ulcer. Gastroenterol Rep 2014;2:235–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chou YH, Wang HY, Hsieh MS. Colonic necrosis in a young patient receiving oral kayexalate in sorbitol: case report and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2011;27:155–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, Rashid A, Wu TT. Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chaudhry HM, Bruce AJ, Wolf RC, Litzow MR, Hogan WJ, Patnaik MS, et al. The incidence and severity of oral mucositis among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: a systematic review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kahan BD. Cyclosporine nephrotoxicity: pathogenesis, prophylaxis, therapy, and prognosis. Am J Kidney Dis 1986;8:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spektor M, Chernyak V, McCann TE, Scheinfeld MH. Gastric pneumatosis: laboratory and imaging findings associated with mortality in adults. Clin Radiol 2014;69:e445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nassereddine S, Rafei H, Elbahesh E, Tabbara I. Acute graft versus host disease: a comprehensive review. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:1547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikiforow S, Wang T, Hemmer M, Spellman S, Akpek G, Antin JH, et al. Upper gastrointestinal acute graft-versus-host disease adds minimal prognostic value in isolation or with other graft-versus-host disease symptoms as currently diagnosed and treated. Haematologica 2018;103:1708–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azevedo LS, Pierrotti LC, Abdala E, Costa SF, Strabelli TMV, Campos SV, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. Clinics 2015;70:515–23.e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med 2013;126:264.e9–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watson MA, Baker TP, Nguyen A, Sebastianelli ME, Stewart HL, Oliver DK, et al. Association of prescription of oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate with sorbitol in an inpatient setting with colonic necrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;60:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]