Abstract

Pathogen-specific immunity evolves in the context of the infected tissue. However, current immune correlates analyses and vaccine efficacy metrics are based on immune functions from peripheral cells. Less is known about tissue-resident mechanisms of immunity. While antibodies represent the primary correlate of immunity following most clinically approved vaccines, how antibodies interact with localized, compartment-specific immune functions to fight infections, remains unclear. Emerging data demonstrate a unique community of immune cells that reside within different tissues. These tissue-specific immunological communities enable antibodies to direct both expected and unexpected local attack strategies to control, disrupt, and eliminate infection in a tissue-specific manner. Defining the full breadth of antibody effector functions, how they selectively contribute to control at the site of infection may provide clues for the design of next-generation vaccines able to direct the control, elimination, and prevention of compartment specific diseases of both infectious and non-infectious etiologies.

Keywords: tissues, immunity, antibody-mediated immunity, antibodies, antibody effector function

Introduction

Pathogens have evolved elaborate mechanisms to establish infection and persistence in various tissues of the human body. In return, each tissue has evolved specialized countermeasures to recognize, control and eliminate foreign invaders1-4. These measures, however, must clear the pathogen without creating pathological side effects, thus, the immune functions within a tissue are delicately balanced to prevent pathogen invasion while also preserving the natural, local cellular and chemical environment5. Conversely, immunological responses that drastically change a tissue’s local milieu can be more acutely pathogenic than the infection itself. Thus, tissue resident immune cells provide the first line of compartment-specific defense. The local environment of a tissue also conditions cells that are recruited from circulation to take on novel programs, enabling them to respond to pathogens in a manner that is appropriate for the local tissue6-9. Understanding the distinct immune mechanisms of pathogen-attack within a tissue offers a new pathway for the rational design of next generation interventions that are poised to directly control pathogens at the site of entry.

The window of opportunity to prevent infection is remarkably short; from the moment the pathogen approaches and enters the body, until it takes residence and begins subverting the immune system. While antibodies able to block infection represent an aspirational goal in all vaccine development, mounting evidence suggests that antibodies may provide protection via additional means, through their ability to control and clear infection, rather than block infection. This second line of defense hinges on the ability of the antibody to work in collaboration with cells of the immune system to effectively recognize and eliminate infection10,11. To this end, antibodies coordinate an attack that leverages both tissue resident cells as well as non-resident cells recruited from other tissues. Moreover, depending on the tissue under attack, the local cellular composition also changes in response to pathogens, coordinating an extraordinary variety of local immune pathways that must work in concert to rapidly clear infection and restore balance.

Antibodies represent the primary correlate of immunity following most clinically approved vaccines12. Antibodies, as mentioned above, interfere with infection in two critical ways: 1) by blocking infection directly in a process termed “neutralization”, or 2) by recruiting the innate immune system to target, sequester, or eliminate pathogens. Neutralization is driven by an antibody’s ability to block pathogen attachment, infectiousness, or prevent virulence, functions or interactions that are required for infection or evasion13. Neutralization represents a critical mechanism of protection against a broad range of pathogens including HIV, Dengue virus, Ebola virus, and others14-16. However, for many infections and clinically approved vaccines, mechanisms beyond neutralization are key to protection. For example, while neutralization can provide protection against influenza viral infection in animal models, it is an incomplete metric of vaccine induced immunity in large human population studies17-21. Instead, the ability of influenza-specific antibodies to recruit natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity against infected cells, initiate phagocytic clearance of the virus and infected cell debris, and to direct complement-mediated destruction of virus particles have all been implicated in protection22. Thus, emerging data suggest that antibody-mediated immunity beyond neutralization, including additional effector functions able to leverage the innate immune system are critical for protection against a wide variety of pathogens. A deeper understanding of the precise antibody functions that naturally resolve infections may provide clues for the rational design of pathogen-targeted therapeutics and vaccines.

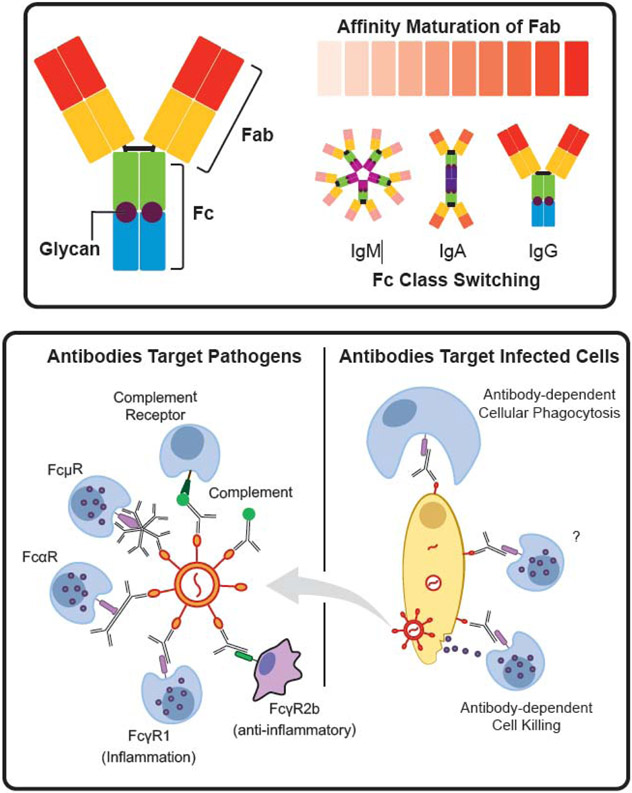

Antibodies are fascinating molecules with two distinct functional domains: the antigen binding domain (Fab) and the constant domain (Fc) (Figure 1, top). Although these domains are structurally independent, they can work together to drive cooperative functions. The Fab domain confers antigen-specificity, which is genetically diversified with remarkable speed through somatic hypermutation in germinal centers23. Through this adaptive process antibodies explore a near infinite evolutionary space in a guided fashion to achieve high affinity and specificity to the target antigen. While the Fab links the antibody and pathogen, the Fc domain connects the antibody to the innate immune system through canonical and non-canonical Fc receptors. Fc receptors are expressed on all innate immune cells24,25 collectively, embodying a truly exceptional breadth of potential functions that can be selectively leveraged by the humoral immune response (Figure 1, bottom). Like the Fab, the Fc-domain is also diversified during an immune response. However, unlike the Fab, the Fc evolves through combinatorial germ line rearrangements of antibody isotypes24 as well as through changes in post-translational glycosylation26 (Figure 1, top). Each Fc isotype and glycoform possesses a distinct combination of affinities for different Fc receptors (FcR), complement, or c-type lectins 10,24. Because these receptors are expressed in different combinations and patterns on cells of the innate immune system, the evolution of distinct Fc-profiles has the capacity to leverage a broad array of functions, depending on the combination of receptors and cells triggered during an immune response. Thus, the landscape of potential antibody effector functions is enormous, governed by a near infinite level of diversity in the Fab coupled to significant heterogeneity in the Fc, resulting in the potential to target pathogens and leverage innate immunity in a remarkably diverse manner.

Figure 1.

Antibody Structure, Diversity and Adaptor Functions. (top) Antibody molecules consist of a Fab region that recognizes the pathogen, an Fc region and a converved N-glycan site. Affinity maturation allows the Fab to explore a nearly infinite space of binding affinities and specificities. Class switching and glycans increase the depth of this variation by creating changes in Fc. The Fc portion bridges an antibody to a variety of effector functions (bottom). Antibodies bound directly to a pathogen (bottom left) can drive complement deposition, which can further connect to cellular responses through complement receptors. Fc receptors for each Fc class exist and are linked to different functions. For example, FcγR1 is activating while FcγR2b is inhibitory. Antibodies can also bind to infected cells (bottom right) and target those cells for destruction via phagocytosis or release of cytotoxic granules.

Moreover, during an immune response, billions of B cells are activated, resulting in the generation of highly diverse pools of antibody secreting cells, each secreting a distinct antibody Fab/Fc combination. Thus, these polyclonal antibody swarms offer additional variation, poised to recognize the pathogen at distinct sites with a multitude of Fc-binding capacities, resulting in the recruitment of the full armamentarium of local and circulating leukocytes to target, control, and clear infection. Importantly, the mechanism of polyclonal antibody action depends significantly on the cellular environment. The distinct community of immune cells that reside in a tissue is charged with supporting normal tissue function, in the absence of infection. However, upon infection, innate immune sentinels that recognize the presence of a pathogen initiate an immune response. Tissue resident immune cells deploy inflammatory signals, cytokines and chemokines, to drive rapid immune infiltrates, arming the tissue further to fight the infectious agent. Given unique cues and pathways that are permitted in specific tissues, the distinct repertoire of functions that may be deployed to fight infection may vary significantly. Thus, antibodies that provide protection against influenza may drive a completely different host of functions in the upper respiratory tract than in the lower respiratory tract, due to the presence of different innate immune cells at different sites of the respiratory mucosa27. Therefore, understanding the site at which antibodies confer protection may provide critical clues related to the specific innate immune mechanisms key to protective immunity.

Fc and Complement Receptors Connect Antibodies to A Broad Array of Innate Functions

Upon binding to a pathogen, antibodies form immune complexes, arrangements of antibodies, that can then be sensed by cell-surface FcRs to initiate a variety of inflammatory and suppressive programs in the cells that express them. In addition, the complement system, a host of secreted Fc sensors, can also interact with immune complexes10. Components of the classical complement pathway, C1q, rapidly bind to the Fc portion of antibody-opsonized immune complexes to initiate a cascade of enzymatic activities. These catalytic reactions not only lead to the deposition of C3b and C3d able to drive further complement deposition and the ultimate formation of the membrane attack complex, but also arm phagocytes for rapid immune complex uptake28,29. These C3, and later C5, decorated immune complexes can interact with complement receptors (CRs) found on nearly all phagocytes, innate immune cells, and even some adaptive immune cells30. However, conversion of C3 and the downstream C5 also lead to the release of C3a and C5a that drive inflammation and activation of immune cells28,29. With our emerging appreciation for the breadth of expression of C3- and C5-receptors across immune cells, complement-decorated immune complexes may have a much broader influence on shaping immunity than once thought 31.

Classical cell surface FcR belong to the immunoglobulin-super-family of receptors that interact with the antibody Fc-domain. In humans, FcRs exist for secreted antibody isotypes (IgG, IgA, IgE, and IgM)32-35. With respect to the IgG-binding FcRs, three major groups exist in humans: the high affinity FcγR1 and the low affinity FcγR2 and FcγR3 32. FcγR2 is further divided into three variants of which FcγR2a (expressed in all humans) and FcγR2c (expressed in only a fraction of the population) are activating, while FcγR2b is inhibitory. Similarly, two variants of FcγR3 exist, including a transmembrane activating FcγR3a and an activating GPI anchor variant, FcγR3b. High and low affinity polymorphic variants have been identified for both FcγR2a and FcγR3a36. In addition, the IgM-specific FcμR receptor, IgA-specific FcαR and IgE-specific FcεR are all activating and broadly expressed across leukocytes37-39, offering additional sensors to take advantage of isotype diversity in immune complex sensing.

Changes in N-linked glycosylation of the antibody Fc-domain can also lead to interactions with c-type lectins. DC-SIGN40, CD2241, CD2342,43 are all lectins that interact with immune complexes. While DC-SIGN is implicated in suppressing inflammation44, CD22 and CD23 are important in the regulation of B cell activation45,46. Changes in Fc glycosylation patterns, such as an increase in sialic acid, are able to alter interactions with these lectins and regulate inflammation and the regulation of antibody production. Additionally, changes in glycosylation of cell proteins, can alter the manner by which antibodies interact with Fc-binding receptors. For example, changes in FcR glycosylation modifies antibody-binding47-49, enabling the immune system to refine the sensitivity of the interaction with immune complexes in the setting of acute versus chronic inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, distinct glycosylation patterns of mucins, large glycan-rich polymers that line all of our mucosal tissues50,51, impact the rates at which immune complexes transit through mucus. By modifying viscosity and charge, glycan:glycan interactions on antibodies alter binding of antibodies and mucins, resulting in altered access of pathogens to the surface of the host52. Indeed, it is plausible that additional, undiscovered antibody receptors may exist that drive novel effector responses, similar to Trim21, an intracellular Fc receptor that was recently discovered53. Thus, a comprehensive definition of antibody sensors in the body may offer critical new insights into both the pathological and protective functions of antibodies in disease.

It is likely that only a fraction of the functions that can be mediated by antibodies has been uncovered. As noted above, antibodies never act alone, but instead form swarms of distinct Fc-domains able to interact differentially with classical and non-classical FcRs. Thus, clusters of FcRs are ligated within synapses on immune cells that lead to the activation of a variety of signal transduction pathways, integrated within the cell to drive anti-pathogen activity. While the level of variation across antibodies and receptors seems daunting to decipher, it provides a near infinite breadth of immune functions that can be explored during infection to fully and completely counteract invasion of the pathogen. For example, defining the number of FcγR2b:FcαR:CR1 receptors that must be ligated on a neutrophil to achieve the ultimate clearance of influenza versus the overall levels of FcμR:CR2:DC-Sign required for the efficient clearance of Streptococci by macrophages may provide critical clues for the design of more sophisticated monoclonal therapeutics or vaccines able to interdict these infections.

The Tissue Specificity of Innate Immune Cells

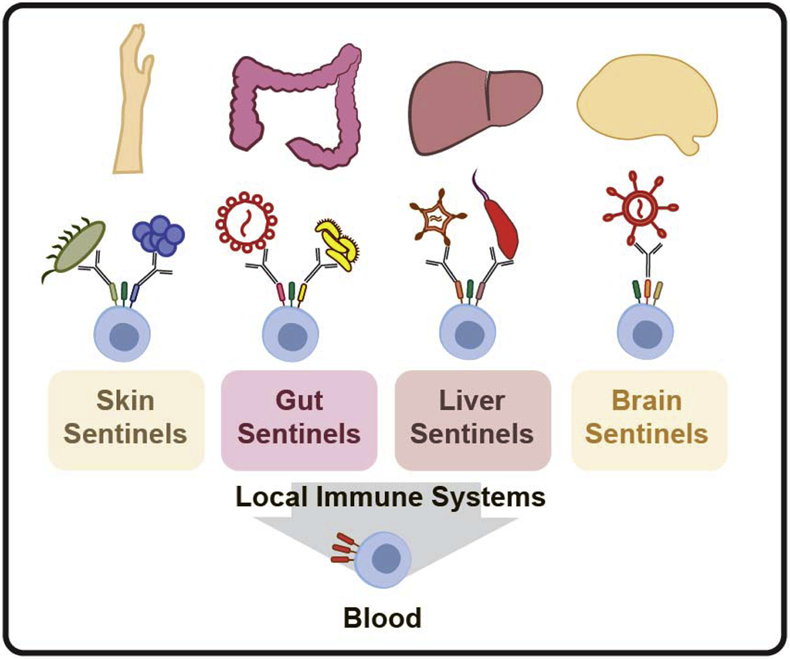

Pathogens invade through diverse tissues to which they have specifically adapted54,55 and in response, the immune system has evolved tissue-specific surveillance and attack strategies. Each tissue harbors functionally distinct innate immune sentinels, poised to detect and immediately respond (Figure 2). These cells are also essential in maintaining local homeostasis, repairing tissue and restoring balance when an inflammatory response is no longer needed. Some immune cells can move between compartments in response to inflammatory cues and then rapidly adapt to the local setting by changing their morphology, activation status, and expression profiles56,57. For example, monocytes migrate through the body in response to signs of infection. The epigenetic profile, phenotype and function of monocytes, however, depends on whether they are in the gut or the skin58. This property is important for mounting a tissue-appropriate response7,59. In the case of autoimmunity or when infection cannot be controlled, a tissue-appropriate response may devolve into a chaotic inflammatory response that overrides the local environment, driving unexpected pathology. Along these lines, dysregulated immune responses have been implicated as a trigger for chronic tissue damage and disease, as has been documented in ulcerative colitis60 and atopic dermatitis61,62. Thus, the immune system must regulate tissue specific functions, even in the face of a pathogen attack, aimed at maintaining tissue integrity and homeostasis.

Figure 2.

Local and peripheral immune responses. Innate tissue-resident sentienels represent the first-line of defense against pathogens. These sentinels express different combinations and levels of antibody Fc receptors that are distinct from innate immune cells in the blood, allowing these cells to mediate tissue-specific immune functions.

Our understanding of the immune correlates of protection against infection in humans is largely grounded in studies that analyze cells isolated from the blood, or the spleen and lymph nodes from mice, due to the convenience of obtaining these samples. This approach, however, does not fully interrogate the breadth of functions available to antibodies at the sites of infection. Because the composition of antibodies and leukocytes that make up the blood are not the same as those that make up the gut, skin, liver or brain, the peripheral correlates of immunity may provide clues, but potentially provide an incomplete mechanistic picture of the immune mechanism(s) required for effective pathogen control and elimination. While a growing body of work has begun to explore the unique mechanistic role of tissue-specific cellular immunity across compartments and diseases, less is known about the protective functional roles of antibodies in different tissues. In this review we discuss emerging research that highlights the importance of antibody effector functions and innate immunity in the context of the skin, gut, liver and brain tissues. Understanding how antibody effector functions bridge to these tissue-specific innate immune systems has the potential to reveal new insights for the next generation of immunotherapies that go beyond neutralization to incorporate tissue-specific innate effector functions.

Antibodies orchestrate immune responses in the skin

The skin is our largest interface between the immune system and the outside world. Skin resident cells must constantly discriminate between friend and foe while also supporting commensalization63,64. To prevent inflammatory responses against everything that passes by, skin immune sentinels generally work to suppress inflammatory cues and maintain tissue integrity65-67. At the same time, local and recruited immune cells perpetually scan the tissue to capture and clear potential invaders. Skin mononuclear phagocytes can be divided to Langerhans cells, the skin resident macrophages, and dermal dendritic cells68,69. Langerhans cells70 exclusively express FcγRII71 and lack expression of FcαR72, while dendritic cells express a wider range of Fc receptors that include FcγRII, FcγRIII25 and FcαR72. Dermal dendritic cells rapidly bind and internalize IgA-opsonized immune complexes through FcαR, resulting in activation and induction of T cell proliferation72-74.

Unique antibody repertoires and FcR expression patterns of skin resident cells create an environment poised to protect the skin against tissue specific pathogens75. The skin IgG repertoire is distinct from circulating IgG, as it includes IgG 1-3 subclasses, but is largely composed of IgG3, while circulating IgGs are predominantly IgG176. Moreover, comparison of heavy chain variable region sequences across the skin and the blood highlighted the unique repertoires of antibodies found across the compartments. Specifically, skin IgG preferentially used variable heavy chain region (VH) families 3 and 5, while circulating IgG were predominantly VH3 and VH4, pointing towards different specificities generated within the different compartments76. Additionally, some of the highest concentrations of IgA in the human body can be found at the skin mucosa, secreted by plasma cells present in cutaneous sebaceous glands and sweat glands77,78, contributing to the presence of unique and distinct antibody populations at the interface of the body’s interaction with microbes.

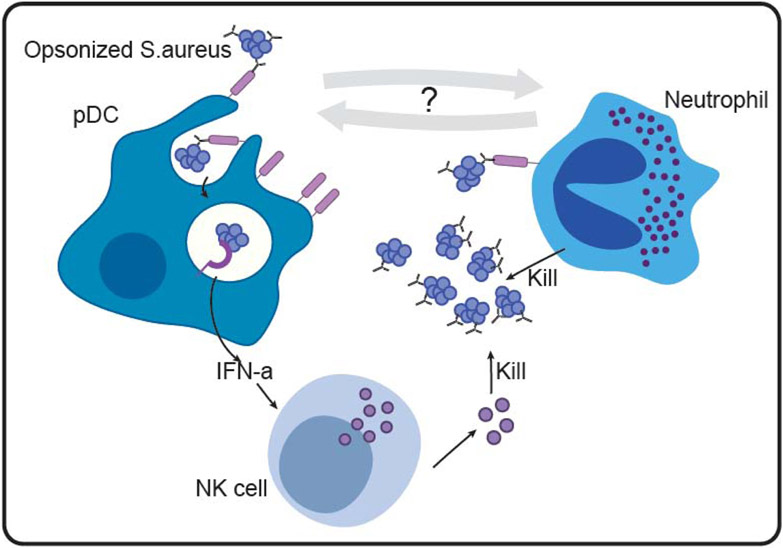

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the leading cause of skin and soft tissue infections, associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to emerging antibiotic resistance79. Antibodies are critical in protection against S.aureus infection, as purified IgG transferred from infected to naïve mice is sufficient for protection against S.aureus induced skin-tissue necrosis80. In contrast to canonical functions of IgG, typically involved in complement deposition or phagocytosis of pathogenic bacteria, IgG protect against S.aureus infection by engaging FcγRIIa expressing plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) that are abundant in healthy skin (Figure 3)81. S.Aureus - IgG complexes bind to FcγRIIa on the surface of pDC and are taken up by endocytosis. Within the endosomal compartment, bacterial nucleic acids bind to TLR7/9 and stimulate pDC activation and IFNα secretion82. IFNα, in turn, alerts NK cells and other immune cells within the tissue to respond and clear the invading pathogen83. In a complementary mechanism, IgA or IgG opsonized S.aureus bind to FcR on the surface of neutrophils to induce a respiratory burst and phagocytosis84. Additionally, IgA binding to Fcαr on the surface of neutrophils induces release of neutrophil extracellular traps that trap, neutralize and kill bacteria85,86. This collection of innate immune functions drive distinct mechanisms of antibody mediated recruitment and deployment of multiple tissue resident immune cell types, ensuring effective and rapid bacterial clearance and return to homeostasis. Whether antibodies deliberately recruit neutrophils and pDCs to collaborate actively in the effort to clear S.aureus infection remains to be studied, but could point to additional functions of antibodies aimed at coordinating attack in a deliberate manner.

Figure 3.

Antibodies orchestrate an effective immune response against S.aureus in the skin. Plasmacytoid DCs (left) bind opsonized S.aureus via FcRs on the cell surface. FcR binding leads to endocytosis and recognition by TLR7/9 within the endosome. TLR7/9 signaling promotes IFNα production and secretion by pDCs. IFNα activates NK cells to kill the pathogen. In parallel, neutrophils (right) sense opsonized S.aureus and are activated to clear the pathogen.

Auto-Inflammatory conditions of the skin, including Atopic Dermatitis (AD), provide direct evidence for the importance of tissue specific antibody mediated functions. AD is marked by chronic inflammation of the skin that is characterized by recurring S. aureus skin infections that contribute to disease severity87. Pathological features of the skin of AD patients include reduced IgA levels88, a lack of Plasmacytoid DCs81 and impaired neutrophil chemotaxis89. Although AD patients develop IgG specific to an array of S.aureus antigens90, they also harbor a distinct antibody profile with decreased S. aureus specific IgG2 and increased IgG491,92. Thus, antibody mediated control of S.aureus infection in AD patients is shifted due to altered antibody repertoires and altered skin-resident immune cell composition, leading to an imbalanced and inefficient antibacterial immune response. A better understanding of antibody mediated functions within the skin, as well as critical interactions of skin sentinels with antibodies, is required to begin to develop tissue appropriate interventions that will benefit AD patients.

In response to efficient antibody mediated protection raised by the host, S. aureus has evolved mechanisms to counteract antibody-mediated recognition and innate responses93. Specifically, protein A is a bacterially encoded FcR, expressed on the surface of S. aureus, that captures IgG with high stoichiometry94, preventing it from triggering immune function. Yet, in addition, S.aureus has also evolved a second antibody countermeasure. IgA-Fc binding is counteracted by staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 7 (SSL7) molecules that bind directly to FcαR and prevents IgA binding 95,96. Additionally, SSL7 suppresses leukocyte-mediated phagocytosis and inflammation by binding to the complement component C5 and interfering with the interaction of C5 with its specific convertase97, thus, preventing its cleavage to form C5a and C5b97. Thus, S. aureus has evolved a network of highly specialized molecules poised to interfere and counteract barrier-specific IgG, IgA and complement mediated immunity, pointing to an array of mechanisms that may be essential for survival in the face of a highly effective IgG and IgA antibody mediated response.

Thus, overall, antibodies protect the skin from infection using direct pathways while also leveraging the cells within the tissue to communicate and mount an appropriate immune response. Chronic skin disorders such as AD provide an opportunity to probe antibody functions within abnormal skin tissue. Namely, in the absence of specific cell types or activation pathways within the tissue, such as pDC or quiescent neutrophils in skin of AD patients, an appropriate immune response cannot be mounted. The measures that pathogens have evolved to escape the diverse mechanisms of the immune system further corroborate the importance of antibody effector functions in combatting infection. Dissecting the factors that confer immune protection within healthy and inflamed skin holds the potential for novel and effective interventions in these patients.

Dynamics of antibody functions in the intestinal tissue

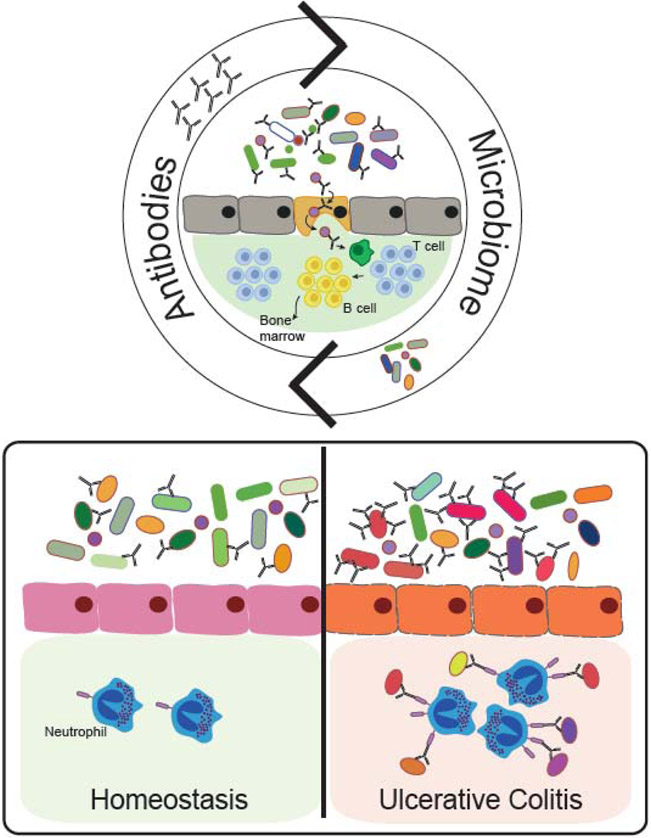

The gut harbors a diverse community of bacteria, fungi and viruses that are carefully pruned by antibody mediated functions throughout life98. Antibodies are constantly secreted into the gut lumen to bind, neutralize and sample microbiome components (Figure 4, Top). For example, IgA regulates gut colonization by directly binding Segmented Filamentous Bacteria (SFB) and limiting their adhesion to the intestinal epithelium99. Importantly, IgA mediated control of the microbiota is not limited to SFB, since 45% of luminal bacteria are IgA bound 100. Instead, emerging data suggest that IgA facilitates sampling and transport of bacteria from the lumen into peyer’s patches, intestinal lymphoid structures, allowing the immune system to perpetually survey the contents of the lumen and ensure the induction of microbiota-specific T cell responses101. Although less is known about microbiome specific-IgG102,103, new data argue that gut-IgG target a broad range of microbial antigens, mostly overlapping with IgA103. Rather, gut-IgG play an essential role in protection against numerous enteric pathogens, including Shigella sonnei, Shigella flexeneri104 and Salmonella typhi105,106.

Figure 4.

Antibody mediated immunity in the gut. Commensal bacteria and the host are in constant dialogue, and antibodies contribute to this conversation. IgA binds to 45% of commensal bacteria in the gut lumen, helping to distinguish friends from foes. The microbiota is continuously sampled by IgA and carried to Peyer’s patches. Within Peyer’s patches microbiota-specific B cells are matured and migrate to the bone marrow, populating the systemic immune response with immunity against enteric bacteria. Conversely, colitogenic bacteria are more densely coated with IgA (bottom panel), activating gut neutrophils and driving their activation and contribution to chronic inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis patients.

Beyond the role of IgA in supporting colonization, IgA-microbiome interactions shape overall gut health107, in part, by inducing microbiome specific IgA responses108,109 that are important both locally and systemically. Germ free mice harbor an immature immune system110,111, characterized by a significant reduction in numbers of intestinal IgA secreting plasma cells and decreased intestinal IgA levels108,112. IgA is locally induced by the microbiota, as fecal IgA levels of germ-free mice rise rapidly upon exposure to E.coli, as early as two weeks after colonization108. Systemically, proteobacteria-rich microbiota induces the generation of long-lived IgA producing plasma cells that home to the bone marrow (Figure 4, Top). These cells continuously produce specific IgA that bind and eliminate gut bacteria that invade the blood113. Overall, microbes and antibodies are involved in a constant dialogue in the gut, that results in a dynamic maintenance of tissue homeostasis.

In parallel to building and maintaining gut homeostasis, antibodies also play a critical role in protection from intestinal pathogens such as attaching and effacing (A/E) bacteria. Citrobacter rodentium is a member of the A/E bacteria family that infects mice and is a widely used model of bacterial infection114. In its pathogenic form, C.rodentium expresses virulence factors encoded within the Locus of Enterocyte Effacement (LEE), including factors that allow the bacterium to adhere and replicate near the epithelial layer114. Intimin is a LEE-encoded virulence factor that is present on the surface of pathogenic C.rodentium114. IgG recognizes and specifically opsonizes Intimin-expressing C.rodentium in the gut lumen. Further, it has been shown that neutrophils transmigrate into the gut lumen where they bind and engulf these opsonized IgG complexes. Interestingly, intestinal neutrophils are crucial for bacterial elimination, and their function cannot not be replaced by intestinal macrophages or monocytes115. However, antibody mediated neutrophil activation is not always beneficial and, in some cases, neutrophils promote inflammation (Figure 4, Bottom). For example, bacteria that are involved in colitis, otherwise known as colitogenic bacteria, are densely coated by IgA compared to commensal bacteria. Given the highly inflammatory nature of IgA-mediated FcαR-activation of neutrophils, these IgA-colitogenic immune complexes may stimulate inflammatory responses116. Indeed, these opsonized targets are rapidly engulfed by FcαR-expressing neutrophils newly recruited to sites of inflammation in the gut tissue117, prior to tissue tolerization, in the context of diseases such as ulcerative colitis118. As opposed to their beneficial role in pathogen clearance, neutrophils remain within colitic tissues, stimulated continuously by IgA-opsonized bacteria binding to Fcαr on their surface, causing tissue damage via net formation and contributing to chronic inflammation119. Thus, beyond their protective role, mis-directed antibodies play a central role in perpetuating the potentially hazardous immune functions of neutrophils within the tissue120,121.

Beyond the canonical functions of antibodies in driving bacterial opsonization, phagocytic uptake and neutrophil activation, IgGs also contribute to antibody mediated protection against enteric viruses through unexpected mechanisms122,123. While many pathogenic bacteria can survive for extended periods of time on host barriers, viruses persist for only short periods of times outside of host cells, clearly resulting in profoundly differing exposure to immune mechanisms of anti-pathogen activity. Thus soluble agents of the immune system, including antibodies and complement factors, must act rapidly to limit viral infection. Conversely, once intracellular, viruses are relatively protected from these soluble agents, however intracellular Fc functions may play a critical role in control of viral infection. For example, Rotavirus is a lethal enteric virus that causes death of ∼200,000 children under the age of 5 annually world-wide, mostly in developing countries124,125. In a neonatal mouse model of Rotavirus infection, IgG-Fc engagement enhanced antiviral protection by reducing Rotavirus-induced disease symptoms126. Namely, administration of a Rotavirus-specific IgG reduced symptom severity after challenge in mice, while mutations that abolished interactions of IgG with the neonatal Fc-receptor(FcRn) or the intracellular Fc-receptor Trim21, abrogated protection126. Despite its name, FcRn is functionally active in human adults127,128 Classically, FcRn is expressed at barrier tissues including the gut and the placenta, where it is involved in transcytosis of antibodies across the barrier. Within the immune system, FcRn is also widely expressed among antigen presenting cells129-131, contributing to antigen presentation to T cells129 implicated in protection against cancer progression132. Conversely, Trim21 is an intracellular FcR that recognizes antibody bound viruses and bacteria within the cytosol, and directs them to proteasomal degradation133,134. Thus, the protective efficacy of Rotavirus-specific IgG may be related to non-canonical FcRn-mediated translocation of antibodies into cytosolic compartments, where the antibodies may act on the virus via the cytosolic Fc-receptor, Trim21, the latter that may rapidly direct the virus for degradation, restriction, and elimination133,134. This proposed unusual axis may represent a unique non-canonical mechanism of antibody action driven by cooperation between FcRn and Trim21 that needs to be further dissected in both Rotavirus and other viral infection models.

Thus, antibodies play a critical role in the gut by shaping the commensal population while protecting against pathogens through both canonical and non-canonical mechanisms. The intestine harbors a distinct repertoire of antibodies poised to populate this unique interface between the host and our symbionts in a way that requires constant vigilance and discrimination between friends and foes. Microbiota composition dynamically shapes this antibody repertoire, setting the stage for potential engineered colonization strategies to guide intestinal innate immune cells towards improved maintenance of tissue health. Yet, as is proposed by possible FcRn/Trim21 cooperation in Rotavirus infection, we are just beginning to skim the surface in our understanding of both canonical and non-canonical mechanisms of protection of antibodies in the gut. Defining the landscape of intestinal Fc receptors, both canonical and non-canonical, and their mode of action in various infection models as well as in chronic inflammatory diseases will lead to improved vaccine development and innovative treatments.

Antibodies are critical mediators of control against liver pathogens

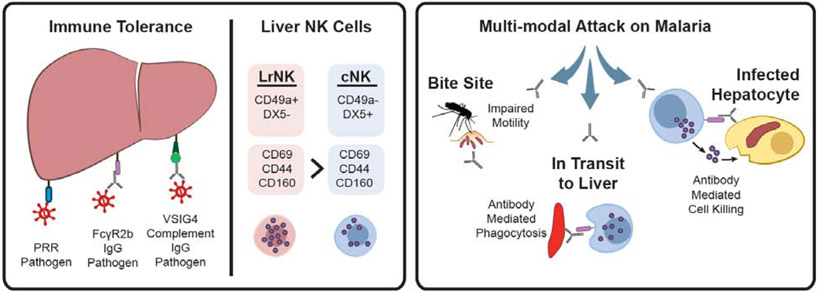

The first stop for nutrients and foreign materials that are absorbed by the gut is the liver, which functions to filter and eliminate waste and debris135. In the liver, a host of resident innate cells work with antibodies to filter out immune complexes without encouraging inflammation. For example, Kupffer cells are liver-resident macrophages that can directly identify the molecular patterns of pathogens and cell damage through pattern recognition receptors (PRR, toll-like receptors and scavenger receptors). Direct binding of antigens to PRRs (Figure 5, left) on both Kupffer cells and hepatocytes triggers phagocytosis without activating inflammatory programs136, thus, pathogens can be directly, and silently removed from circulation.

Figure 5.

Antibody-mediated Functions in the Liver. (left) The liver play a critical role in filtering foreign antigens and immune-complexes (left) through direct recognition by pattern recognition receptors (PRR) or by binding to antibodies or complement found within immune-complexes. The liver is one of the most prominent sites of inhibitory FcγR2b expression, which induces immune-complex uptake in the absence of inflammation, while the complement receptor VSIG4 on Kupffer cells also drives tolerogenic activity following immune-complex uptake. The liver is also host to a large population of natural killer (NK cells), divided into tolerogenic liver-resident NK cells (LrNK) or inflammatory NK cells (cNK), that are poised to respond to infection within the tissue under the correct activating signals. (right) Parasitic infection of the liver can be prevented by the malaria vaccine, RTS,S, via the induction of antibodies able to: recruit NK cell killing of the parasite, phagocytic clearance of the parasite, or the immobilization of the parasite.

Among the debris that is actively eliminated by the liver, the liver plays a central role in filtering IgG-opsonized antigens using the inhibitory FcγR2b receptor137,138 to dampen systemic inflammation (Figure 5, left). In fact, the liver is one of the most prominent sites of FcγR2b expression138,139 which is found on both Kupffer cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs)139. FcγR2b at the surface of LSECs has been shown to direct rapid BSA-DNP immune complex clearance, prior to recycling back to the cell surface in rats140, where it continues to filter additional complexes. Moreover, a four-fold reduction in the clearance of IgG-opsonized ovalbumin has been observed in FcγR2b−/− mice138. Additionally, immune complexes may also be decorated with components of the complement system that are filtered by binding to the V-set immunoglobulin domain 4 (VSIG4) receptor, a complement receptor expressed on Kupffer cells. Critically, binding to VSIG4 inhibits the activation of inflammatory programs through the PI3K/Akt-STAT3 pathway141,142. Thus, although the liver is constantly interacting with antibody/complement-coated immune complexes, canonical inflammatory programs are locally suppressed via interactions with FcγR2b and VSIG4.

In addition to housing its own community of cells that are tailored to silently remove immune complexes from the blood, the composition of leukocytes in the liver is also drastically different than that of the blood. For example, NK cells represent 30-50% of the lymphocytes found in the liver138 but only 13% of lymphocytes in the blood145. Half of these liver NK cells resemble canonical, circulating CD49a−/DX5+ NK (cNK) cells, while the other half are CD49a+/DX5 and specifically home to the liver upon transplantation in mice146,147 (Figure 5, left). These liver-resident NK (LrNK) cells express higher levels of inhibitory Ly48E and NKG2a receptors than cNK, suggesting that LrNK exhibit a tolerant phenotype despite higher levels of FcγRIIIa expression147. Based on this profile, LrNK are uniquely poised and ready for degranulation upon immune complex sensing, but this potential is heavily restrained through inhibitory receptors that prevent hyperactivity and tissue damage.

NK cells are important front-line responders against both liver-tropic viruses and parasites, such as malaria. Malaria is a mosquito-borne parasite causing over 400,000 deaths annually148. Malaria is transmitted to humans through a mosquito bite, where transmitted sporozoites from the mosquito can reside in the skin for as long as 15 minutes149 prior to trafficking to the liver, the primary site of initial parasitic infection. Interestingly, treatment with IgG1 monoclonal antibodies have been shown to provide protection in mice, simply by delaying motility and trapping parasites at the site of infection150 (Figure 5, right), representing a novel antibody function. However, antibodies have been implicated in protection against malaria infection at several additional stages of infection, both in the liver as well as in the blood, once the parasite enters the second stage of the infection as a merozoite.

Importantly, although antibodies have been implicated in protection at various stages of malaria infection, vaccines are likely to have the greatest impact at the bottleneck of infection, when the sporozoites infect the liver. The most advanced malaria vaccine, RTS,S, is a recombinant protein-based vaccine that targets the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) expressed on the surface of the sporozoite. The RTS,S vaccine confers 50-90% protection in naïve adult challenge experiments151-156. While antibody titers have been linked to protection 153, antibody levels alone do not explain all observed protection, particularly in children in field studies157-160. Conversely, comprehensive antibody functional profiling identified antibody-mediated recruitment of NK cell cytotoxicity and monocyte phagocytosis as key correlates of protection against malaria infection161 (Figure 5, right). Moreover, in vivo CSP-specific monoclonal mediated protection was compromised in the presence of a silenced Fc-domain, clearly implicating canonical Fc-mediated NK cell and monocyte functionality in limiting malaria infection. Whether these functions occur during sporozoite transit from the skin to the liver, or are mediated by resident Kupfer cells (liver resident macrophages) or cNK/LrNK cells remains unclear. However, the data point to the possibility that the induction of highly functional antibodies able to leverage the large proportion of liver resident NK cells and phagocytes in the liver could be ideal in fighting against liver pathogens. A careful understanding of how antibodies may tip the inflammatory balance, allowing the activation of tolerant LrNK and inflammatory cNK in the liver can reveal new pathways to develop an effective vaccine against malaria.

Thus the liver represents an organ loaded with innate immune effectors poised to respond to antibodies via both canonical and non-canonical FcRs. As the largest producer of complement, the liver is primed for antibody mediated destruction. However, cells within this tissue are heavily controlled, loaded with inhibitory receptors and residing in an anti-inflammatory milieu. Ultimately, strategies aimed at leveraging function within this unique immunological compartment may require unique solutions, and may unlock the remarkable armamentarium positioned in this tissue to battle both infections and oncogenic targets that may traffic through this critical organ.

Antibodies mediate both pathology and regeneration in the brain

The skin, gut, and liver are immunologically distinct tissues that present unique functional repertoires in response to pathogens. Antibodies and leukocytes that home to these tissues from circulation are also major players in local responses. The blood, however, is separated from brain tissue and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds the brain and spinal cord by two critical barriers. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) guards capillaries in the brain parenchyma and is composed of a layer of brain microvascular endothelia (BMVEC) encapsulated by astrocyte endfeet processes, which, together, tightly regulate the passage of material and nutrients into and out of the tissue162 (Figure 6, left). The blood-CSF barrier (BCSFB) can be found in the meninges and the choroid plexus, where CSF is produced. Unlike the BBB, the BCSFB is composed of fenestrated endothelia that permit the passage of materials from the blood into an interstitial space that is surrounded by choroid epithelia and tight junctions, which regulate the passage of materials into the CSF163. The brain, spinal cord and CSF that surrounds them are encapsulated by the meninges, a multi-layered tissue that houses its own interstitial CSF layer and BCSFB structures that regulate CNS transport.

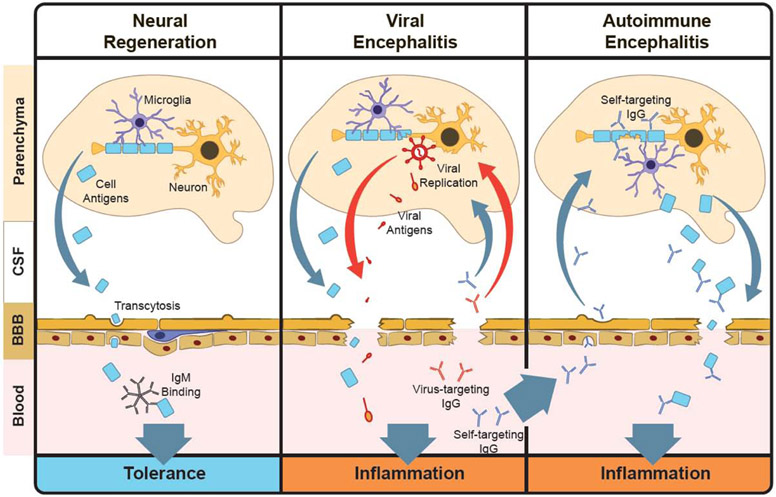

Figure 6.

Antibody-mediated Regeneration and Pathology in the Brain. (left) The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is separated from blood via a blood-brain barrier (BBB). Under normal conditions microglia remove cell debris from neurons and other cells. This debris leaks through the BBB into the blood, where it may be captured by low-affinity natural IgM, promoting immune tolerance. (middle) Viral encephalitis is an inflammation in the brain that is driven by viral replication. Debris from damaged cells, viral antigens, and inflammatory cytokines secreted by microglia leak through the BBB and induce inflammation. The resulting humoral response includes functional antibodies against both viral and self antigens, which promote BBB breakdown and perpetuates inflammation in the brain. (right) Self-targeting antibodies may be present in the humoral repertoire, where they can be activated later, in the absence of viral replication. These antibodies can mediate cell destruction and inflammation through microglia, resulting in BBB breakdown and igniting autoimmune encephalitis.

These barriers pose a major challenge for antibody therapies that need to target central nervous system (CNS) components. In healthy individuals, antibody concentrations in the CSF are >1000-fold lower than they are in the blood. For example, although intravenously delivered amyloid-targeting antibodies could be found in the CSF of mice, they comprised only 1/1000th of the original intravenous dose164,165. This is, partly, due to active export of antibodies from the CNS driven by Fc receptors like FcRn, where CSF clearance of IgG1 Fc variants depended on FcRn binding affinity166. Interestingly, BMVEC transcytosis, at the level of the BBB, has been shown to be inhibited by Fc sialic acid moieties in vitro, suggesting that some Fc-IgG1 variants may persist for longer periods in the brain parenchyma167. Although antibodies are not normally produced in the CNS, gut-derived IgA-secreting B cells have been shown to home to the dura matter of the venous sinuses, where secreted dimeric IgA have been implicated in protection of the CNS against invasion by gut flora168. Mechanisms of antibody transport into the CNS, however, have not yet been clearly defined, although recent evidence suggests an FcRn-independent mechanism of abluminal antibody transport into the BBB in vitro169. In agreement with this, antibody-opsonization has been shown to have a limited effect the transcytosis of HIV-1 particles across immortalized human cerebral microvascular endothelia monolayers in vitro170. Interestingly, both the brain microvascular endothelia of the BBB and choroid plexus epithelia of the BCSFB express FcRn {12067234}, thus, both are potential sites of antibody transfer into the CNS.

Neurological autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS) are driven by immune responses that target the myelin sheaths of axons, resulting in a loss of electrical conductivity and neuronal death. In addition to CNS-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells, antibody-dependent complement activity has also been implicated as a prominent mechanism of pathology in MS. A recent study showed that complement deposition mediated by myelin-targeting antibodies drives demyelination of neural axons in mouse brain tissue sections and in vitro171. Antibodies have also been implicated as key diagnostic markers of MS, as elevated levels of IgG in the CSF (>7ug/mL) are indicative of a neurological autoimmune disorder. Interestingly, these antibodies are oligoclonal, suggesting a specific repertoire of antibodies accumulate in the CSF that differ from circulating antibodies in the blood. These antibodies may be produced locally, as gut-derived IgA-secreting B cells have also recently been shown to home to the CNS during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice172. Moreover, recent phage display studies aimed at profiling both the specificity and the quality of these antibodies in 20 MS patients show that there was an enrichment of primarily IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses in CSF173 that may activate inflammation in microglia, the macrophages of the brain, which express FcγRI, FcγRIIB, and FcγRIII174, or by activating innate cells after efflux from the CSF to the blood. These IgG may accelerate inflammation in the brain by targeting intracellular proteins associated with cell damage173,175.

Antibodies can also be found in the CSF during viral infection. Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) primarily infects the trigeminal nerve, which extends from the brainstem and branches into three primary sections that, collectively, direct sensation and motor functions in the face. HSV1 infection results in a life-long latent infection that can reactivate to produce cold sores or, however, it can also reactivate in the brain resulting in HSV-induced encephalitis (HSVE). Replication in the brain induces local inflammatory responses that can damage and alter leukocyte recruitment and the permeability of the BBB176,177. CNS infection of mice with murine hepatitis virus (MHV) produces virus-specific memory and antibody-secreting B cells that cross these barriers and home to the CNS, after maturing in cervical lymph nodes178. Similarly, in humans, HSV replication in the CNS may be restrained by neutralizing IgG and IgA antibodies in the CSF, where HSV-specific IgG and IgA can be detected in the CNS Of some patients even a year after symptom onset179. Autoimmune encephalitis (AE) has been proposed to emerge following the concomitant flow of viral antigens, inflammatory signals and CNS antigens that leak across the permeated barriers from through draining lymph nodes (Figure 6, center) following HSV reactivation. In fact, HSVE is associated with a high, 27% risk of autoimmune encephalitis (AE), which can occur in as little as two months after the primary encephalitis180. Within days of HSVE symptoms, antibodies targeting the N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) expressed on neurons181 can be detected, suggesting that inflammatory responses against self-antigens develop in the context of an inflammatory response following viral reactivation (Figure 6, center) that may trigger AE after the virus has been cleared (Figure 6, right). Although NMDAR targeting antibodies include IgG, IgA and IgM classes, IgG is more specifically found in the CSF182 than in circulation, which may activate pathogenic functions in microglia through Fc-receptor binding. Understanding the functional nature of these CNS-localized antibodies and the cells that produce them may point to novel immunological pathways connecting HSV replication in the brain to autoimmune encephalitis.

Antibodies, however, also play a role in neural development and regeneration (Figure 6, left). Low affinity, autoreactive IgMs drive B cell tolerance and participate in tissue regeneration by targeting debris and damaged cells in both a direct and complement-mediated fashion183-185. Microglia express the IgM receptor, FcμR, which has been shown to mediate IgM and complement-dependent phagocytosis of bacteria in a microglia cell line186 Naturally produced, low affinity IgM with broad specificity, termed ‘natural IgM’, are ubiquitous and play an important role in humoral tolerance by recognizing self-antigens187. In a screen of patients with non-MS associated monoclonal gammopathy, a myelin-targeting IgM (rHIgM22) was isolated and shown to promote oligodendrocyte maturation and remyelination in vitro. This regenerative function was driven by microglia in an Fc and complement-dependent fashion188. Remarkably, rHIgM22 and several other monoclonal human IgMs that target CSF-specific antigens promote remyelination in mouse models of MS and viral infection189,190. Thus, while high affinity auto-reactive antibodies in the CSF are pathological indicators, low levels of self-reactive IgM may participate in neural regeneration.

The composition of the CSF is uniquely tailored to providing nutrients and maintaining the electrical conductivity in neurons, thus, highly selective barriers are needed to ensure that only the right components are extracted from the blood and deposited into the CSF. Understanding the mechanisms that differentiate between the regenerative role of natural IgM and the pathological role of IgG may reveal new strategies for driving therapeutic functions in the CNS.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Traditional vaccines have successfully conquered and even eliminated many pathogenic infectious diseases. However, vaccine development has fallen short against pathogens like tuberculosis, malaria and HIV. Novel, innovative approaches are urgently needed to combat these as well as novel emerging pathogens. A ‘one size fits all‘ vaccine modality is economical and simplifies production. However, a one size fits all solution may not be possible for all pathogens. While traditional strategies focusing on blocking infection have failed, our emerging appreciation for the unique and multi-faceted roles of antibodies in providing protection against infection offer new opportunities to develop next-generation therapeutics and vaccines. Thus, a better understanding of antibody mechanism of action, with a deeper appreciation for the cellular-milieu where the antibody must drive protection may offer design opportunities that will revolutionize therapeutic design.

Acknowledgement

We thank Nancy Zimmerman, Mark and Lisa Schwartz, an anonymous donor and Terry and Susan Ragon for their support. This work was supported by R37AI80289, R01AI146785, R01AI152158, U01CA260476 and the Ragon Institute. BB is a Zuckerman-CHE postdoctoral scholar.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Disclosures

Dr. Alter is the founder of Systems Seromyx Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Janeway CA Jr How the immune system protects the host from infection. Microbes Infect 3, 1167–1171 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matzinger P & Kamala T Tissue-based class control: the other side of tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol 11, 221–230 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okabe Y & Medzhitov R Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat Immunol 17, 9–17 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medzhitov R Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotas ME & Medzhitov R Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell 160, 816–827 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uderhardt S, Martins AJ, Tsang JS, Lämmermann T & Germain RN Resident Macrophages Cloak Tissue Microlesions to Prevent Neutrophil-Driven Inflammatory Damage. Cell 177, 541–555.e17 (2019).This paper shows how resident skin macrophages maintain tissue homeostasis by preventing infiltrating neutrophils from causing tissue damage.

- 7.Bain CC et al. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6C hi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 498–510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenne CN et al. Neutrophils recruited to sites of infection protect from virus challenge by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe 13, 169–180 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodward Davis AS, Bergsbaken T, Delaney MA & Bevan MJ Dermal-Resident versus Recruited γδ T Cell Response to Cutaneous Vaccinia Virus Infection. J. Immunol 194, 2260–2267 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM & Alter G Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 46–61 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruhns P & Jönsson F Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol Rev 268, 25–51 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plotkin SA Complex correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 56, 1458–1465 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL & Wilson IA Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science vol. 337 183–186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sok D & Burton DR Recent progress in broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV. Nat Immunol 19, 1179–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corti D et al. Tackling influenza with broadly neutralizing antibodies. Curr Opin Virol 24, 60–69 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Law M et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat Med 14, 25–27 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sicca F, Neppelenbroek S & Huckriede A Effector mechanisms of influenza-specific antibodies: neutralization and beyond. Expert Rev Vaccines 17, 785–795(2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Memoli MJ et al. Evaluation of Antihemagglutinin and Antineuraminidase Antibodies as Correlates of Protection in an Influenza A/H1N1 Virus Healthy Human Challenge Model. MBio 7, e00417–16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skowronski DM et al. Randomized controlled trial of dose response to influenza vaccine in children aged 6 to 23 months. Pediatrics 128, e276–89 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heikkinen T & Heinonen S Effectiveness and safety of influenza vaccination in children: European perspective. Vaccine 29, 7529–7534 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki S et al. Limited efficacy of inactivated influenza vaccine in elderly individuals is associated with decreased production of vaccine-specific antibodies. J Clin Invest 121, 3109–3119 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P & Ravetch JV Broadly neutralizing hemagglutin in stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20, 143–151 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng G & Papavasiliou FN Immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Genet 41, 107–120 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nimmerjahn F & Ravetch JV Fc-receptors as regulators of immunity. Adv Immunol 96, 179–204 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilliams M, Bruhns P, Saeys Y, Hammad H & Lambrecht BN The function of Fcγ receptors in dendritic cells and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol 14, 94–108 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang TT & Ravetch JV Functional diversification of IgGs through Fc glycosylation. J Clin Invest 129, 3492–3498 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renegar KB, Small PA, Boykins LG & Wright PF Role of IgA versus IgG in the Control of Influenza Viral Infection in the Murine Respiratory Tract. J. Immunol 173, 1978–1986 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V & Roumenina LT Complement System Part I - Molecular Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Front Immunol 6, 262 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merle NS, Noe R, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Fremeaux-Bacchi V & Roumenina LT Complement System Part II: Role in Immunity. Front Immunol 6, 257 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll MC The complement system in regulation of adaptive immunity. Nature Immunology vol. 5 981–986 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubbers R, van Essen MF, van Kooten C & Trouw LA Production of complement components by cells of the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol 188, 183–194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pincetic A et al. Type I and type II Fc receptors regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol 15, 707–716 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Egmond M et al. IgA and the IgA Fc receptor. Trends Immunol 22, 205–211 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutton BJ & Davies AM Structure and dynamics of IgE-receptor interactions: FcεRI and CD23/FcεRII. Immunol Rev 268, 222–235 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubagawa H et al. The old but new IgM Fc receptor (FcμR). Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 382, 3–28 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagelkerke SQ, Schmidt DE, de Haas M & Kuijpers TW Genetic Variation in Low-To-Medium-Affinity Fcγ Receptors: Functional Consequences, Disease Associations, and Opportunities for Personalized Medicine. Front Immunol 10, 2237 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubagawa H et al. Functional Roles of the IgM Fc Receptor in the Immune System. Front Immunol 10, 945 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breedveld A & van Egmond M IgA and FcαRI: Pathological Roles and Therapeutic Opportunities. Front Immunol 10, 553 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraft S & Kinet J-P New developments in FcepsilonRI regulation, function and inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 365–378 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X, Vasiljevic S, Mitchell DA, Crispin M & Scanlan CN Dissecting the molecular mechanism of IVIg therapy: the interaction between serum IgG and DC-SIGN is independent of antibody glycoform or Fc domain. J Mol Biol 425, 1253–1258 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang L et al. Identification of Siglec Ligands Using a Proximity Labeling Method. J Proteome Res 16, 3929–3941 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi J et al. Interaction of the low-affinity receptor CD23/Fc epsilonRII lectin domain with the Fc epsilon3-4 fragment of human immunoglobulin E. Biochemistry 36, 2112–2122 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhaliwal B et al. Crystal structure of IgE bound to its B-cell receptor CD23 reveals a mechanism of reciprocal allosteric inhibition with high affinity receptor FcεRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 12686–12691 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Karlsson MCI & Ravetch JV Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 19571–19578 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pezzutto A, Dörken B, Moldenhauer G & Clark EA Amplification of human B cell activation by a monoclonal antibody to the B cell-specific antigen CD22, Bp 130/140. J. Immunol 138, (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnefoy JY, Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Aubry JP, Gauchat JF & Graber P CD23 and B-cell activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol 7, 355–359 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wojcik I et al. Site-specific glycosylation mapping of Fc gamma receptor IIIb from neutrophils of individual healthy donors. Anal. Chem (2020) doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel KR, Nott JD & Barb AW Primary human natural killer cells retain proinflammatory IgG1 at the cell surface and express CD16a glycoforms with donor-dependent variability. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 18, 2178–2190 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayes JM et al. Glycosylation and Fc receptors. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology vol. 382 165–199 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGuckin MA, Lindén SK, Sutton P & Florin TH Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 9, 265–278 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V & McGuckin MA Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol 1, 183–197 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phalipon A et al. Secretory component: a new role in secretory IgA-mediated immune exclusion in vivo. Immunity 17, 107–115 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.James LC, Keeble AH, Khan Z, Rhodes DA & Trowsdale J Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 6200–6205 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woolhouse MEJ, Webster JP, Domingo E, Charlesworth B & Levin BR Biological and biomedical implications of the co-evolution of pathogens and their hosts. Nature Genetics vol. 32 569–577 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LEBARBENCHON C, BROWN SP, POULIN R, GAUTHIER-CLERC M & THOMAS F Evolution of pathogens in a man-made world. Mol. Ecol 17, 475–484 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luster AD, Alon R & von Andrian UH Immune cell migration in inflammation: Present and future therapeutic targets. Nature Immunology vol. 6 1182–1190 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beltman JB, Marée AFM & De Boer RJ Analysing immune cell migration. Nature Reviews Immunology vol. 9 789–798 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ginhoux F & Jung S Monocytes and macrophages: Developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nature Reviews Immunology vol. 14 392–404 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schridde A et al. Tissue-specific differentiation of colonic macrophages requires TGFβ receptor-mediated signaling. Mucosal Immunol. (2017) doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuchroo VK, Ohashi PS, Sartor RB & Vinuesa CG Dysregulation of immune homeostasis in autoimmune diseases. Nature Medicine vol. 18 42–47 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hijnen D et al. Cyclosporin A reduces CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T-cell numbers in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124, 856–858 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bilsborough J et al. IL-31 is associated with cutaneous lymphocyte antigen-positive skin homing T cells in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 117, 418–425 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belkaid Y & Segre JA Dialogue between skin microbiota and immunity. Science (80-. ). 346, 954–959 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naik S et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science (80-. ). 337, 1115–1119 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark RA & Kupper TS IL-15 and dermal fibroblasts induce proliferation of natural regulatory T cells isolated from human skin. Blood 109, 194–202 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flacher V et al. Murine Langerin+ dermal dendritic cells prime CD8+ T cells while Langerhans cells induce cross-tolerance. EMBO Mol Med 6, 1191–1204 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shklovskaya E et al. Langerhans cells are precommitted to immune tolerance induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 18049–18054 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kissenpfennig A et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity 22, 643–654 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaplan DH In vivo function of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Trends Immunol 31, 446–451 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doebel T, Voisin B & Nagao K Langerhans Cells - The Macrophage in Dendritic Cell Clothing. Trends Immunol 38, 817–828 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmitt DA et al. Human epidermal Langerhans cells express only the 40-kilodalton Fc gamma receptor (FcRII). J Immunol 144, 4284–4290 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geissmann F et al. A subset of human dendritic cells expresses IgA Fc receptor (CD89), which mediates internalization and activation upon cross-linking by IgA complexes. J Immunol 166, 346–352 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamre R, Farstad IN, Brandtzaeg P & Morton HC Expression and modulation of the human immunoglobulin A Fc receptor (CD89) and the FcR gamma chain on myeloid cells in blood and tissue. Scand J Immunol 57, 506–516 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bakema JE & van Egmond M The human immunoglobulin A Fc receptor FcαRI: a multifaceted regulator of mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunol 4, 612–624 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin J-Z & Nickoloff BJ Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 9, 679–691 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saul L et al. IgG subclass switching and clonal expansion in cutaneous melanoma and normal skin. Sci Rep 6, 29736 (2016).The authors analyze skin IgG repertoires in healthy donors and melanoma patients, comparing them to circulatory IgG.

- 77.Metze D et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of immunoglobulin A in human sebaceous and sweat glands. J Invest Dermatol 92, 13–17 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okada T, Konishi H, Ito M, Nagura H & Asai J Identification of secretory immunoglobulin A in human sweat and sweat glands. J Invest Dermatol 90, 648–651 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL & Fowler VG Jr Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 28, 603–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Montgomery CP et al. Protective immunity against recurrent Staphylococcus aureus skin infection requires antibody and interleukin-17A. Infect Immun 82, 2125–2134 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wollenberg A et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a new cutaneous dendritic cell subset with distinct role in inflammatory skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol 119, 1096–1102 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parcina M et al. Staphylococcus aureus-induced plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation is based on an IgG-mediated memory response. J Immunol 181, 3823–3833 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyaki E et al. Interferon alpha treatment stimulates interferon gamma expression in type I NKT cells and enhances their antiviral effect against hepatitis C virus. PLoS One 12, e0172412 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gorter A et al. IgA- and secretory IgA-opsonized S. aureus induce a respiratory burst and phagocytosis by polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Immunology 61, 303–309 (1987). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aleyd E et al. IgA enhances NETosis and release of neutrophil extracellular traps by polymorphonuclear cells via Fcα receptor I. J Immunol 192, 2374–2383 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Papayannopoulos V Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 134–147 (2018).This review describes the role of neutrophil extracellular traps in tissue damage associated with autoantibodies in autoimmune disease.

- 87.Park H-Y et al. Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Acute and Chronic Skin Lesions of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Ann Dermatol 25, 410–416 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imayama S et al. Reduced secretion of IgA to skin surface of patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 94,195–200 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhingra N et al. Attenuated neutrophil axis in atopic dermatitis compared to psoriasis reflects TH17 pathway differences between these diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132, 498–501.e3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Totté JEE et al. IgG response against Staphylococcus aureus is associated with severe atopic dermatitis in children. Br J Dermatol 179, 118–126 (2018).By analyzing IgG responses to 55 S.aureus antigens the authors define the humoral immune landscape of children with Atopic Dermatitis.

- 91.Mrabet-Dahbi S et al. Deficiency in immunoglobulin G2 antibodies against staphylococcal enterotoxin C1 defines a subgroup of patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy 35, 274–281 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Orfali RL et al. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B induces specific IgG4 and IgE antibody serum levels in atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol 54, 898–904 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Foster TJ Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat Rev Microbiol 3, 948–958 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Uhlén M et al. Complete sequence of the staphylococcal gene encoding protein A. A gene evolved through multiple duplications. J Biol Chem 259, 1695–1702 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wines BD, Wlloughby N, Fraser JD & Hogarth PM A competitive mechanism for staphylococcal toxin SSL7 inhibiting the leukocyte IgA receptor, Fc alphaRI, is revealed by SSL7 binding at the C alpha2/C alpha3 interface of IgA. J Biol Chem 281, 1389–1393 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ramsland PA et al. Structural basis for evasion of IgA immunity by Staphylococcus aureus revealed in the complex of SSL7 with Fc of human IgA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 15051–15056 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bestebroer J et al. Functional basis for complement evasion by staphylococcal superantigen-like 7. Cell Microbiol 12,1506–1516 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kubinak JL & Round JL Do antibodies select a healthy microbiota? Nat Rev Immunol 16, 767–774 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suzuki K et al. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 1981–1986 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van der Waaij LA, Mesander G, Limburg PC & van der Waaij D Direct flow cytometry of anaerobic bacteria in human feces. Cytometry 16, 270–279 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lécuyer E et al. Segmented filamentous bacterium uses secondary and tertiary lymphoid tissues to induce gut IgA and specific T helper 17 cell responses. Immunity 40, 608–620(2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen K, Magri G, Grasset EK & Cerutti A Rethinking mucosal antibody responses: IgM, IgG and IgD join IgA. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 427–441 (2020).This review highlights the role of antibody classes other then IgA in mucosal surfaces.

- 103.Fadlallah J et al. Synergistic convergence of microbiota-specific systemic IgG and secretory IgA. J Allergy Clin Immunol 143, 1575–1585.e4 (2019).Here the authors show that both serum IgA and IgG are microbiome specific, and their specificities overlap.

- 104.Robin G et al. Characterization and Quantitative Analysis of Serum IgG Class and Subclass Response to Shigella sonneiand Shigella flexneri2a Lipopolysaccharide following Natural ShigellaInfection. J. Infect. Dis 175,1128–1133 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee SJ et al. Identification of a common immune signature in murine and human systemic Salmonellosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 4998–5003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liang L et al. Immune profiling with a Salmonella Typhi antigen microarray identifies new diagnostic biomarkers of human typhoid. Sci. Rep 3,1–10(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Palm NW, de Zoete MR & Flavell RA Immune-microbiota interactions in health and disease. Clin Immunol 159,122–127 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hapfelmeier S et al. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Science (80-. ). 328, 1705–1709 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Koch MA et al. Maternal IgG and IgA Antibodies Dampen Mucosal T Helper Cell Responses in Early Life. Cell 165, 827–841 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL & Blumberg RS How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science (80-. ). 352, 539–544 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kennedy EA, King KY & Baldridge MT Mouse Microbiota Models: Comparing Germ-Free Mice and Antibiotics Treatment as Tools for Modifying Gut Bacteria. Front Physiol 9, 1534 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stefka AT et al. Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 13145–13150 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wilmore JR et al. Commensal Microbes Induce Serum IgA Responses that Protect against Polymicrobial Sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 23, 302–311.e3 (2018).In this paper the role of microbiome induced IgA in protection against sepsis was elegantly demonstrated

- 114.Collins JW et al. Citrobacter rodentium: infection, inflammation and the microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 12, 612–623 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kamada N et al. Humoral Immunity in the Gut Selectively Targets Phenotypically Virulent Attaching-and-Effacing Bacteria for Intraluminal Elimination. Cell Host Microbe 17, 617–627(2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Palm NW et al. Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 158, 1000–1010(2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fournier BM & Parkos CA The role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 5, 354–366 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van der Steen L et al. Immunoglobulin A: Fc(alpha)RI interactions induce neutrophil migration through release of leukotriene B4. Gastroenterology 137, 2013–2018(2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Muthas D et al. Neutrophils in ulcerative colitis: a review of selected biomarkers and their potential therapeutic implications. Scand J Gastroenterol 52, 125–135 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Weiss SJ Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med 320, 365–376 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Smith DJ Jr, Jones CS, Hull M, Robson MC & Kleinert HE Bioprosthesis in hand surgery. J Surg Res 41, 378–387(1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Westerman LE, McClure HM, Jiang B, Almond JW & Glass RI Serum IgG mediates mucosal immunity against rotavirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 7268–7273(2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chachu KA et al. Antibody Is Critical for the Clearance of Murine Norovirus Infection. J. Virol 82, 6610–6617 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Angel J, Franco MA & Greenberg HB Rotavirus immune responses and correlates of protection. Curr Opin Virol 2, 419–425 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Parashar UD & World Health Organization-Coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Global, Regional, and National Estimates of Rotavirus Mortality in Children <5 Years of Age, 2000-2013. Clin Infect Dis 62 Suppl 2, S96–S105 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]