Abstract

Mincle agonists have been shown to induce inflammatory cytokine production, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha the (TNF) and promote the development of a Th1/Th17 immune response that may be crucial to development of effective vaccination against pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. As an expansion of our previous work, a library of 6,6΄-amide and sulfonamide α,α-d-trehalose compounds with various substituents on the aromatic ring were synthesized efficiently in good to excellent yields. These compounds were evaluated for their ability to activate the human C-Type Lectin Receptor Mincle by the induction of cytokines from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. A preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR) of these novel trehalose diamides and sulfonamides revealed that aryl amide-linked trehalose compounds demonstrated improved activity and relatively high potency cytokine production compared to the Mincle ligand trehalose dibehenate adjuvant (TDB) and the natural ligand trehalose dimycolate (TDM) inducing dose-dependent and human Mincle specific stimulation in a HEK reporter cell line.

Keywords: Adjuvant, Mincle, Vaccine, Tuberculosis, TH-17, Trehalose

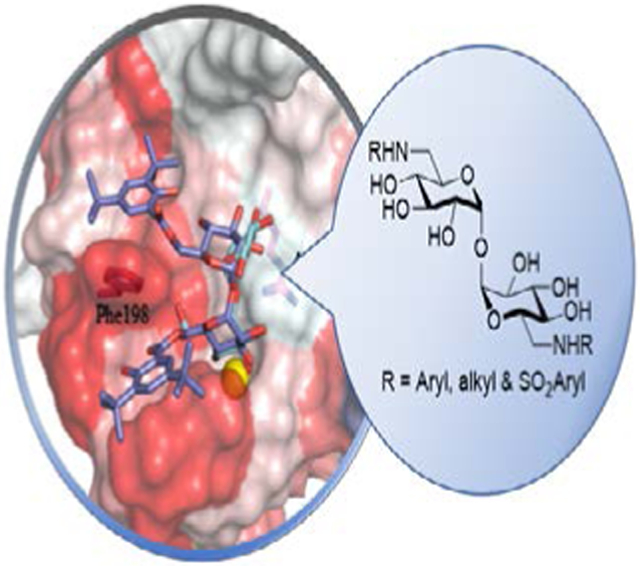

Graphical Abstarct

The discovery of novel adjuvants capable of eliciting a Th17 adaptive immune as a correlate of protection in vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a potential avenue toward addressing the global impact of this pathogen. We report the preparation of a library of amide linked aryl trehalose compounds capable of activating Mincle selective cytokines and demonstrate a sulfonamide linker is not tolerated.

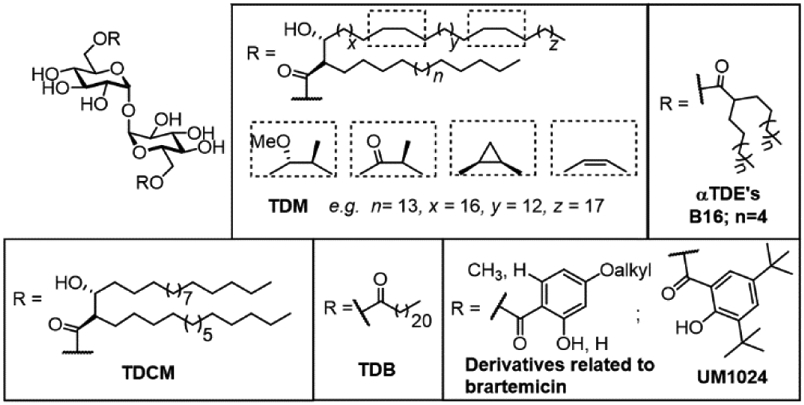

Vaccination against infectious pathogens is perhaps the most promising and potentially effective tool in combating global morbidity/mortality and health disparity from infectious diseases. Notwithstanding the great success of vaccines, the development of new, safe, and effective vaccine is still required for emerging new pathogens, re-emerging pathogens, and the inadequate protection conferred by some existing vaccines.1 Newly arising immunization approaches such as subunit vaccines have increased the need for potent and selective adjuvants, particularly adjuvants inducing cell-mediated immune responses.2 A breakthrough was the identification of the macrophage inducible C-type lectin (Mincle, Clec4e, or Clecf9) as a pattern recognition receptor (PRR) on the surface of macrophages and dendritic cells activated through ligation of trehalose dimycolate (TDM), the major component of Mycobacterium cell wall and its synthetic analogues trehalose-6,6’-dicorynomycolate (TDCM) and trehalose dibehenate (TDB) (Figure 1). 3,4 TDM and TDB have the ability to stimulate the innate and early adaptive immune response that has led to an interest in the potential of these molecules as adjuvants.5 In particular, TDB has shown promise as a vaccine adjuvant for both tuberculosis and HIV when formulated in the CAF01 liposome system.6 TDM, TDB, and TDCM7a, demonstrated that these glycolipids are potent agonists,7 although TDM and TDCM have proven to be too reactogenic for human vaccine applications.8 The development of TDB and other trehalose diesters (TDEs),9,10,11 has partially met the need for new adjuvants although the physiochemical properties of these adjuvants, being very lipophilic with limited aqueous solubility, limits their application to complex liposomal formulations.12 Brartemicin, a trehalose-based natural product, has been reported as a high-affinity ligand of the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) of the C-type lectin Mincle.13 In recent years several lipidated diaryl derivatives have been described to elicit Th17 cytokines in a Mincle-dependent fashion with improved adjuvant activity and physical properties over TDB.10b,14 The synthesis and evaluation of the first relatively small 6, 6΄-aryl ester trehalose (UM1024; Figure 1) was recently reported, with demonstrated ability to promote a Th1/Th17 immune response invitro and invivo.15 The results reported here further explore the structural basis for the activity of this new class of Mincle signaling compounds and identify structural motifs responsible for immune activation with the potential to improve physiochemical properties, in particular solubility, for use as vaccine adjuvants. Also, evaluation of Mincle crystal structures16 suggested improved calcium metal/ligand affinity in the proposed binding pocket in addition to improved interactions of adjacent glutamine and arginine moieties through the replacement of the 6,6′-ester with amide or sulfonamide functionality.

Figure 1.

Representative Mincle ligands: Trehalose Dimycolates (TDM), α-Trehalose Diesters (αTDE’s, B16), Trehalose Dicorynomycolates (TDCM), Trehalose dibehenate (TDB), Brartemicin analogues, and UM1024.

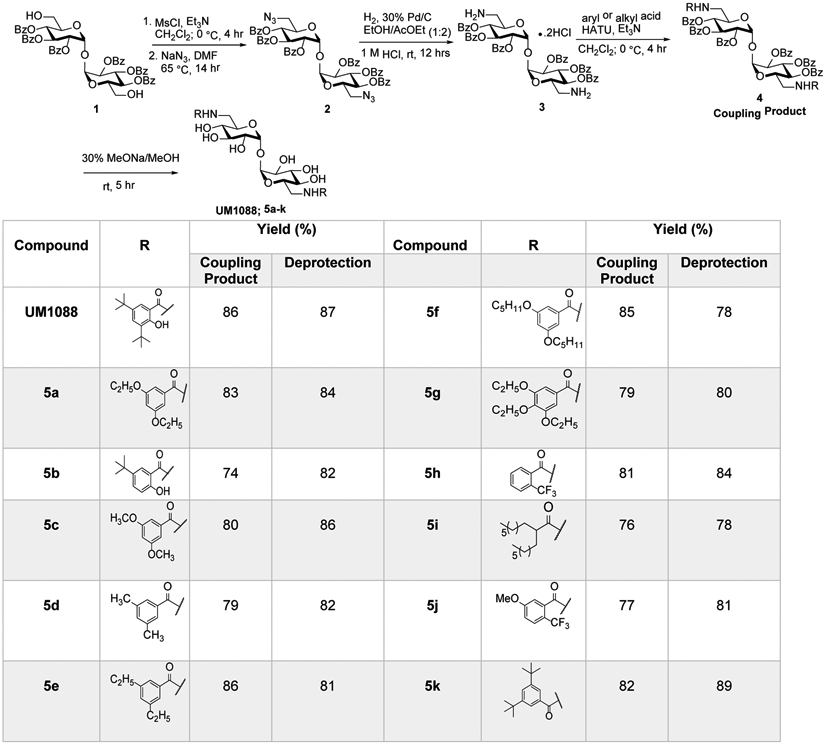

As our continued interest in exploring the potential utility of 6,6΄-aryl α,α-D-trehalose analogues on Mincle-binding and cytokine signaling as vaccine adjuvants have generated several novel compounds with improved potency and solubility over the currently available Mincle ligands such as TDB and TDM.13,14,17,18 The natural extension of structure-activity studies is the synthesis of 6,6΄-aryl amide α,α-D-trehalose and 6,6΄-aryl sulfonamide α,α-D-trehalose analogues related to previously prepared ester analogues17b to investigate the impact of the aryl-trehalose linkage on Mincle selective cytokine signaling. 6,6’-diamino trehalose (3) is a key intermediate for the synthesis of the targeted trehalose diamides (TDA’s) was obtained as shown in Figure 2. Mesylation of primary alcohols of Hexa-O-benzolated trehalose18a (1) followed by azidation under standard conditions furnished the diazide in good yield. In the catalytic hydrogenation of diazide (2), the presence of hydrochloride is necessary to block the well-known oxygen-to-nitrogen benzoyl migration. Alkoxy aryl acids that were not commercially available were prepared from the corresponding hydroxy arylbenzoates. Methyl 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate and methyl 3,4,5-dihydroxybenzoate were alkylated using requisite alkyl bromides followed by ester hydrolysis providing the desired benzoic acid derivatives in excellent yields over two steps.19 Similarly, the aliphatic branched carboxylic acid (B16) was synthesized starting from diethyl malonate over 4 steps in good yield.8a The trehalose diamide derivatives were then assembled via HATU mediated amidation of 6,6΄-diamino trehalose (3) with carboxylic acid (2.5 equiv. per 1 equiv. of OBz-protected trehalose). Having accomplished the synthesis of the protected diamides (4), all that remained was the global deprotection of benzoyl groups using conventional NaOMe in MeOH conditions to obtain the target compounds (UM1088, 5a-k; Figure 2) that were fully characterized by spectroscopic techniques (see Supplementary Methods for details).

Figure 2:

Synthesis of a focused library of 6,6’diaryl and alkyl amide trehalose Mincle signaling compounds

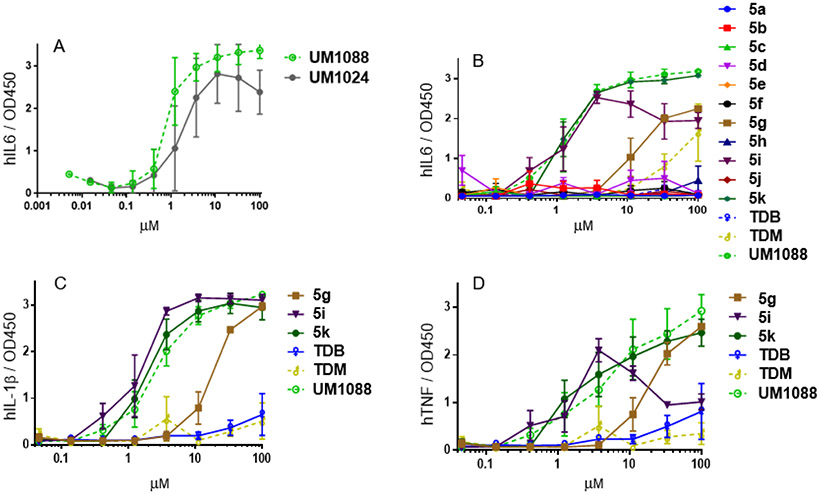

Mincle agonists have been shown to induce inflammatory cytokine production, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha the (TNF), and promote the development of a Th1/Th17 immune response that is associated with and dependent on induction of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23.20 Therefore, for preliminary screening, the synthesized compounds were assayed for IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β production in human PBMC’s (Figure 3).8a,21 Briefly, compounds were serially diluted in ethanol, applied to tissue culture plates and the solvent was evaporated. Freshly isolated human PBMCs were added and incubated with the compound for 18-24 hours. Supernatants were collected and evaluated for IL-6 levels by ELISA. TDB and TDM, which are Mincle ligands,5 were used as a positive control in the assay. Recently, Lang and co-workers22 demonstrated IL-6 production by stimulation of isolated APCs with TDM and TDB. The experiments reported here use PBMCs and thus the IL-6 levels are lower than reported in the literature for these Mincle ligands. In addition, the solvent used for plate coating greatly influences the responsiveness of PBMCs to these compounds (data not shown). Here, we used ethanol as the solvent whereas other reports in the literature have used isopropyl alcohol or other solvents. Ethanol was selected to maximize the in vitro activity of our synthetic compounds and may not be optimal for the activity of TDM or TDB. We presume this difference is due to conformation obtained in the drying process of the compound which is critical for the activity/activation of these PRR’s. Studies are ongoing to further explore the tertiary structural requirements of Mincle receptor binding and activation by what we presume to be nanoparticles.

Figure 3: Cytokine production of UM1024, TDB, TDM, UM1088, 5a-k.

Cytokine production from primary human mononuclear cells in response to stimulation with synthetic trehalose diamide compounds. (A) and (B) The indicated compound was dissolved in ethanol, serially diluted, and then dried to the bottom of a tissue culture plate. Fresh PBMCs were purified, applied to the compound-coated plates, and incubated at 37°C; the supernatant was harvested 24 h later. (C) and (D) Selected IL-6 positive compounds were subsequently analyzed for TNF, IL-1β via an ELISA. Graphs are mean values from 3 donors +/− SEM.

Initially, we investigated the ability of aryl amide analogue UM1088 for the production of IL-6 in comparison with our previously reported potent relatively small Mincle Signaling compound UM1024 (Figure 1; Figure 3A).17b UM1088 was observed to be equipotent to UM1024 and surprisingly did not exhibit a decline in potency at high concentrations as observed for UM1024 and most other Mincle ligands tested to date. Currently, we are postulating that compound aggregation at high concentrations is responsible for this observation as we do not observe activation-induced cell death at high compound concentrations of UM1024 and we observe a similar profile for compounds such as 5h.

Analysis of the remaining library of compounds containing amide functionality was tested for IL-6 production with Mincle signaling compounds, TDB, TDM, and UM1088 a positive controls (Figure 3B). Compounds containing the sterically bulky group, i-e tert-butyl group, at 3 and 5 positions (5k) led to significant production of IL-6 as compared to less sterically hindered groups at 3 and 5 positions. For example, 5d or ethyl at 3 and 5 position (5e) resulted in a loss of activity. In the same way, 3,5 diether derivatives with the extension of the hydrocarbon chain, methyl (5c), ethyl (5a), and pentyl (5f), gave little to no response. In contrast, 3,4,5-triether compound (5g) resulted in modest production of IL-6. From our previous studies in synthesizing the aryl trehalose compounds, analogues with methyl or more importantly a trifluoromethyl group at the 2-position of the aromatic ring resulted in strong IL-6 production from human PBMCs21 but with amide linkage, the compound containing trifluoromethyl group at 2-position (5h and 5j) had little to no IL-6 production from human PBMCs. Additionally, it was found that moving the tert-butyl group to the 5-position (5b) resulted in a loss of activity.

In addition to IL-6, we investigated the production of the inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-1β using the IL-6 active compounds (5g, 5i and 5k) to determine if indeed we are potentially driving a Th1 or Th17 biased adaptive immune response. As illustrated, these compounds produce appreciable quantities of TNF and IL-1β (Figure 3c & d). 5i demonstrated similar cytokine levels and potency to that of reported Th17-inducing vaccine adjuvant candidate α-TDE compound B16.8a Further investigations into immunomodulatory properties, adjuvant activity and mode of action of 5i are currently underway.

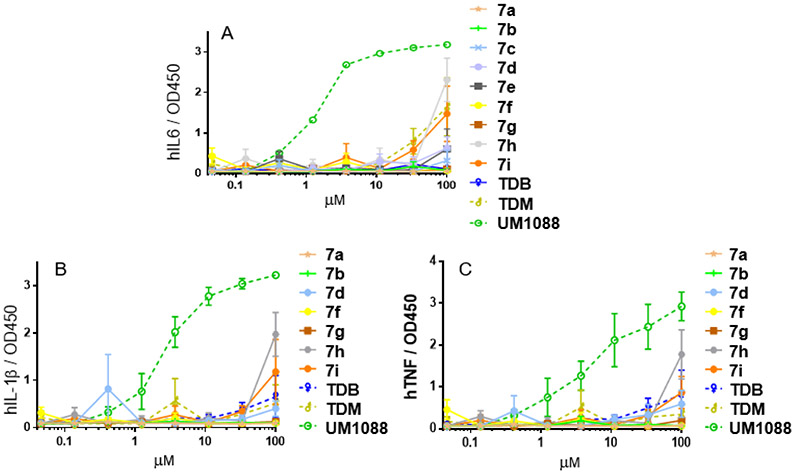

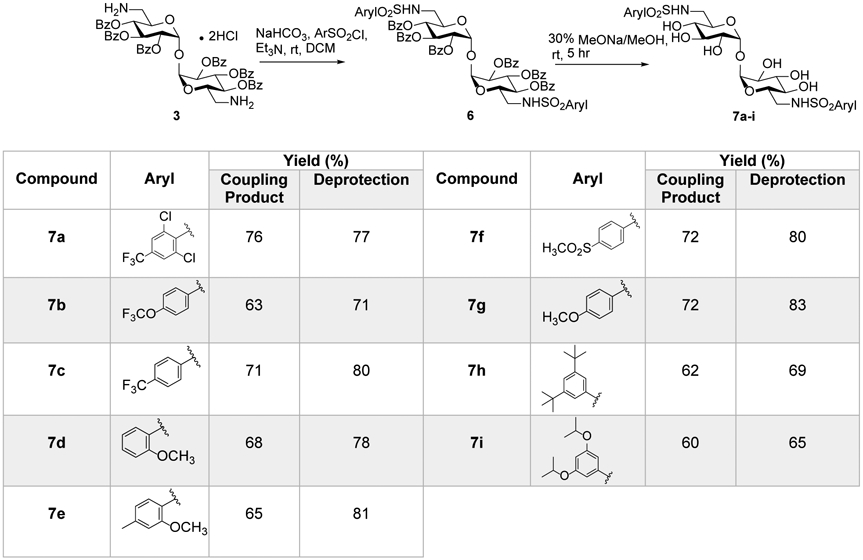

Sulfonamides have been a central functional group in molecules with a wide spectrum of biological activities.24 With the observation that incorporation of the amide linker potentially improved activity versus an ester linkage we decided to introduce a very polar sulfonamide functional group for the preparation of a diverse selection of new compounds (Figure 4). The synthesis of sulfonamide analogues was easily investigated using commercially available sulfonyl chlorides and our advanced intermediate 6,6’-amine (3). The free base form of trehalose diamine was generated in situ using solid NaHCO3 and reacted with aryl sulfonyl chlorides in CH2Cl2 solution in the presence of Et3N to provided amide intermediates in good to excellent yields.25 Standard global benzoyl deprotection with NaOMe/MeOH gave the target compounds (7a-i) as solids in good yields (Figure 4). The compounds were fully characterized by 1H, 13C NMR, and high-resolution mass spectrometry. From previous work and the trehalose amide derivatives presented here, we hypothesized that Mincle activity was very sensitive to aryl substitution patterns and a high degree of hydrophobicity may not be required to maintain activity, but a high degree of steric bulk at 3 and 5 positions markedly improves IL-6 cytokine production. Therefore, the sulfonyl linked analogue of UM1088 and 5k were prepared. The 3,5 tert-butyl substituted aryl sulfonyl chlorides are not commercially available but we were able to synthesize these using the reported method of Huntress, et. al.26 These sulfonyl chlorides were then used in coupling reactions under optimized reaction conditions followed by deprotection to isolate the derivatives. After several attempts, we were not able to isolate the corresponding sulfonamide analogue of UM1088 but we were able to synthesize 7h, the sulfonamide analogue of 5k. These compounds were assayed for the secretion of inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 in human PBMC’s.5 Surprisingly, compounds bearing the sulfonamide functional group did not promote IL-6 production from human PBMCs (Figure 5) with the exception of low- level activity observed for plate coated 7h and 7i. The response was verified through the observed mild production of TNF and IL-1β only at the high concentrations.

Figure 4:

Synthesis of a focused library of 6,6’diaryl sulfonamide trehalose compounds.

Figure 5: Cytokine production of UM1088, TDB, TDM, and 7a-i.

Cytokine production from primary human mononuclear cells in response to stimulation with synthetic trehalose diamide compounds. (A) The indicated compound was dissolved in ethanol, serially diluted, and then dried to the bottom of a tissue culture plate. Fresh PBMCs were purified, applied to the compound-coated plates, and incubated at 37°C; the supernatant was harvested 24 h later. (B) and (C) Selected IL-6 positive compounds were subsequently analyzed for TNF, IL-1β via a ELISA. Graphs are mean values from 3 donors +/− SEM.

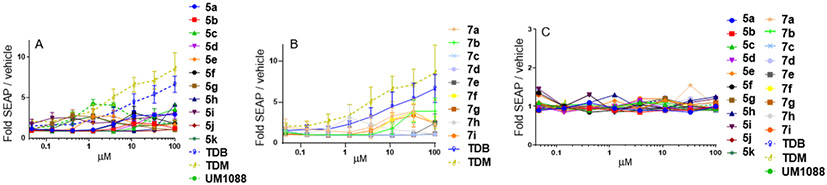

To confirm the demonstrated cytokine activity was Mincle specific the compounds were evaluated for their ability to signal through human Mincle using human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK) cells expressing the human Mincle receptor along with an NF-κB-driven secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter (see Supplementary Methods for details). Several of the analogues were observed to induce the production of SEAP in a dose-dependent manner. HEK null cells (HEK cells containing the NF-κB reporter without Mincle receptor) were used as negative controls to confirm receptor specificity of the compounds (Figure 6). In a similar fashion to UM1024, UM1088 demonstrated a strong dose-response in the hMincle HEK reporter cells. Similarly, 5a and 5c showed a moderate dose-dependent increase in SEAP production from hMincle HEK cells.

Figure 6: Activation of human Mincle in response to TDM, TDB, and synthesized trehalose 6,6’diaryl amide trehalose derivatives.

A) and B) The indicated compounds were plate coated and hMincle HEK NF-κB-SEAP reporter cells were incubated with the compounds for 24 h followed by assessment of the supernatants for SEAP levels. C) results in HEK null cells Data are represented as fold change in OD650 over vehicle-treated cells. Graphs are mean values from three independent experiments ± SEM.

The rest of the compounds with different substitutions on the aromatic ring were unable to induce measurable SEAP production from hMincle HEK reporter cells. Surprisingly, several of the sulfonamide analogues were able to induce the production of SEAP in a dose-dependent manner. However, the ability of sulfonamide to signal through hMincle was lower than their amide counterparts. Further investigations into immunomodulatory properties and mode of action of these TDAs are currently underway.

In summary, the systematic expansion of our recent report on the synthesis and evaluation of the novel and very potent Mincle active compound UM1024 has demonstrated the exchange of an amide for ester linker markedly improved responses for the most active compounds. However, incorporation of the sulfonamide in this scaffold appears to be deleterious to Mincle activity. This study reinforces our previous findings that a high degree of steric bulk at the 3 and 5 positions drastically improves Mincle specific cytokine production specifically for the ester and amide scaffolds. While it was surprising that analogues bearing the sulfonamide were relatively inactive this finding suggests a crucial interaction of the linker in the receptor and we intend to further the understanding of these interactions using molecular dynamics simulations. Extension of SAR and biological activity of these and similar molecules are ongoing in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a NIAID Adjuvant Discovery Program Contract (HHSN272201400050C). The authors acknowledge University of Montana Core Services of the Center for Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics (CBSD) and the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry supported by the National Institutes of General Medical Science (NIH CoBRE grant P20GM103546) for NMR and MS instrumentation. The authors acknowledge the University of Montana Office of Research and Creative Scholarship for support.

Footnotes

Institute and/or researcher Twitter usernames: @umontana

References

- 1.a) Lee S, Nguyen MT, Immune Netw., 2015, 15, 51–57; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) L-Roels G, Vaccine, 2010, 28S, C25–C36. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riese P, Schulze K, Ebensen T, Prochnow B, Guzman CA, Current Top. Med. Chem, 2013, 13 (20), 2562–2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Matsumoto M, Tanaka T, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Akira S, J. Immunol, 1999, 163, 5039–5048; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Foster AJ, Nagata M, Lu X, Lynch AT, Omahdi Z, Ishikawa E, Yomasaki S, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, J. Med. Chem, 2018, 61, 3, 1045–1060; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Matsunaga I, Moody DB, J. Exp. Med, 2009, 206, 2865–2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Fomsgaard A, Karlsson I, Gram G, Schou C, Tang S, Bang P, Kromann I, Andersen P, Andreasen LV, Vaccine 2011, 29 , 7067–74; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schoenen H, Bodendorfer B, Hitchens K, Manzanero S, Werninghaus K, Nimmerjahn F, Agger EM, Stenger S, Andersen P, Ruland J, Brown GD, Wells C, Lang R, J. Immunol, 2010, 184 , 2756–2760; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ishikawa E, Ishikawa T, Morita YS, Toyonaga K, Yamada H, Takeuchi O, Kinoshita T, Akira S, Yoshikai Y, Yamasaki S, J. Exp. Med, 2009, 206 , 2879–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird JH, Khan AA, Nishimura N, Yamasaki S, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, J. Org. Chem, 2018, 83, 7593–7605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottenhoff TH, Doherty MT, van Dissel JT, Bang P, Lingnau K, Kromann I, Andersen P, Human Vaccines, 2010, 6, 1007–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) van der Peet PL, Gunawan C, Torigoe S, Yamasaki S, Williams SJ, Chem. Comm, 2015, 51, 5100–5103; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nisihizawa M, Yamamoto H, Imagawa H, -Chassefiere VB, Petit E, Azuma I, -Garcia DP, J. Org. Chem, 2007, 72, 1627–1633; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shenderov K, Barber DL, Mayer-Barber KD, Gurcha SS, Jankovic D, Feng CG, Oland S, Hieny S, Caspar P, Yamasaki S, Lin X, Ting JP, Trinchieri G, Besra GS, Cerundolo V, Sher A, J. Immunol 2013, 190, 5722–5730; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Werninghaus K, Babiak A, Gross O, Holscher C, Dietrich H, Agger EM, J Exp Med., 2009, 206, 89–97; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hunter RL, Olsen MR, Jagannath C, Actor JK, Ann Clin Lab Sci., 2006; 36, 371–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Smith AJ, Miller SM, Buhl C, Child R, Whitacre M, Schoener R, Ettenger G, Burkhart D, Ryter K, Evans JT, Front. Immunol, 2019, 10, 338; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Christensen D, Chapter 17 - Development and Evaluation of CAF01 A2 - Schijns, Virgil EJC In Immunopotentiators in Modern Vaccines (Second Edition), O'Hagan DT, Ed. Academic Press: 2017; pp 333–345; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson DA, Carbohydrate Research, 1992, 237, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Mohanraj M, Sekar P, Liou H-H, Chang S-F, Lin W-W, Molecular Neurobiology, 2019, 56, 1167–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamamoto H, Oda M, Nakano M, Watanabe N, Yabiku K, Shibutani M, Inoue M, Imagawa H, Nagahama M, Himeno S, Setsu K, Sakurai J, Nishizawa M, J. Med. Chem, 2013, 56, 381–385; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Khan AA, Chee SH, Mclaughlin RJ, Harper JL, Kamena F, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, ChembioChem, 2011, 12, 2572–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Foster AJ, Bird JH, Timmer MSM,Stocker BL, “The ligands of C-Type lectins” In C-Type Lectin Receptors in Immunity; Yamasaki S, Ed., Ch. 13, Springer: Japan, 2016; [Google Scholar]; b) Braganza C, Teunissen T, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, Front. Immunol 2018, 8, 1940; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Foster AJ, Kodar K, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2020, 18, 1095–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidsen J, Rosenkrands I, Christensen D, Vangala A, Kirby D, Perrie Y, Agger EM, Andersen P, Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2005, 1718 , 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobsen KM, Keiding UB, Clement LL, Schaffert ES, Rambaruth DS, Johannsen M, Drickamer K, Poulsen TB, Med. Chem. Commun, 2015, 6, 647–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Stocker BL, Kodar K, Wahi K, Foster AJ, Harper JL, Mori D, Yamasaki S, Timmer MSM, Glycoconj. J, 2019, 36, 69–78; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khan AA, Kodar K, Timmer MSM, Stocker BL, Tetrahedron, 2018, 74, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y-L, Tang L-Q, Miyanaga S, Igarashi Y, Saiki I, Liu ZP, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2011, 21, 1089–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Feinberg H, et al. J. Biol. Chem, 2013, 288(40): 28457–28465; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Furukawa A, et al. "Structural analysis for glycolipid recognition by the C-type lectins Mincle and MCL." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110, 17438–17443; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jegouzo SAF, et al. Glycobiology, 2014, 24, 1291–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Burkhart D, Ettenger G, Evans J, Ryter KT, Smith A, PCT Int. Appl, 2019, 131pp., WO2019165114; [Google Scholar]; b) Ryter KT, Ettenger G, Rasheed OK, Buhl C, Child R, Miller SM, Holley D, Smith AJ Evans JT, J. Med. Chem, 2020, 63, 309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Jiang Y-L, Li S-X, Liu Y-L, Ge L-P, Han X,-Z, Liu Z-P, Chem. Bio & Drug Des, 2015, 86, 5, 1017–1029; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khan AA, Stocker BL, Timmer MSM, Carbohydr. Res, 2012, 356, 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Perec V, Wilson DA, Leowanawat P, Wilson CJ, Hughes AD, Kaucher MS, Hammer DA, Levine DH, Kim AJ, Bates FS, Davis KP, Lodge TP, Klein ML, Devane RH, Aqad E, Rosen BM, Argintaru AO, Sienkowska MJ, Rissanen K, Nummelin S, Ropponen J, Science, 2010, 328, 1009–1014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roder N, Marzalek T, Limbach D, Pisula W, Detert H, ChemPhysChem, 2019, 20, 463–469; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kikkawa Y, Nagasaki M, Koyama E, Tsuzuki S, Hiratan K, Chem. Com, 2019, 3955–3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desel C, Werninghaus K, Ritter M, Jozefowski K, Wenzel J, Russkamp N, Schleicher U, Christensen D, Wirtz S, Kirschning C, Agger EM, Prazeres da CC, Lang R, PLoS One, 2013, 8 , e53531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Srenathan U, Steel K, Taams LS, Immunology Lett., 2016, 178, 20–26; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kimura A, Kishimota T, Eur. J. Immunol, 2010, 40, 1830–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostrop J, Jozefowski K, Zimmermann S, Hofmann K, Strasser E, Lepenies B, Lang R, J. Immunol, 2015, 2417–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasheed OK, Ettenger G, Buhl C, Child R, Miller SM, Evans JT, Ryter KT, Bioorg. & Med. Chem, 2020, 28, 115564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Chen Y, Synthesis, 2016, 2483–2522; [Google Scholar]; b) Thota N, Makam P, Rajbongshi KK, Nagiah S, Abdul NS, Chuturgoon AA, Kaushik A, Lamichhane G, Somboro AM, Kruger HG, Govender T, Naicker T, Arvidsson PI, ACS Med. Chem. Lett, 2019, 10, 1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose JD, Maddry JA, Comber RN, Suling WJ, Wilson LN, Reynolds RC, Carb. Res 2002, 337, 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a) Huntress EH, Carten FH, J. Am. Chem, 1940, 62, 511–514; [Google Scholar]; b) Bovino MT, Chemler SR, Ang. Chem. Int, 2012, 51, 3923–3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.