Abstract

Background:

Current treatments for erectile dysfunction (ED) are ineffective in prostatectomy and diabetic patients due to cavernous nerve (CN) injury, which causes smooth muscle apoptosis, penile remodeling and ED. Apoptosis can occur via the intrinsic (caspase 9) or extrinsic (caspase 8) pathway.

Aim:

We examined the mechanism of how apoptosis occurs in ED patients and CN injury rat models, to determine points of intervention for therapy development.

Methods and Outcomes:

Immunohistochemical and western analyses for caspase 3-cleaved, −8 and −9 (pro and active forms) were performed in corpora cavernosal tissue from Peyronie’s, prostatectomy and diabetic ED patients (n=33), penis from adult Sprague Dawley rats that underwent CN crush (n=24), BB/WOR diabetic and control rats (n=8), and aged rats (n=9).

Results:

Caspase 3-cleaved was observed in corpora cavernosa from Peyronie’s patients, and at higher abundance in prostatectomy and diabetic tissues. Apoptosis takes place primarily through the extrinsic (caspase 8) pathway in penis tissue of ED patients. In the CN crushed rat, caspase 3 cleaved was abundant from 1–9 days after injury, and apoptosis takes place primarily via the intrinsic (caspase 9) pathway. Caspase 9 was first observed and most abundant in a layer under the tunica, and after several days was observed in the lining of and between the sinuses of the corpora cavernosa. Caspase 8 was observed initially at low abundance in the rat corpora cavernosa, and was not observed at later time points after CN injury. Aged and diabetic rat penis primarily exhibited intrinsic mechanisms, with diabetic rats also exhibiting mild extrinsic activation.

Clinical translation:

Knowing how and when to intervene to prevent the apoptotic response most effectively, is critical for development of drugs to prevent ED, morphological remodeling of the corpora cavernosa, and thus disease management.

Strengths and limitations:

Animal models may diverge from the signaling mechanisms observed in ED patients. While the rat utilizes primarily caspase 9, there is significant flux through caspase 8 early on, making it a reasonable model, as long as the timing of apoptosis is considered after CN injury.

Conclusions:

Apoptosis takes place primarily through the extrinsic caspase 8 dependent pathway in ED patients, and via the intrinsic caspase 9 dependent pathway in commonly used CN crush ED models. This is an important consideration for study design and interpretation that must be taken into account for therapy development and testing of drugs, and our therapeutic targets should ideally inhibit both apoptotic mechanisms.

Keywords: caspase, apoptosis, extrinsic, intrinsic, erectile dysfunction, cavernous nerve injury, peripheral nerve regeneration, penis

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a common and debilitating medical condition that affects 52% of men aged 40–701, and their partners. Risk factors include age, cardiovascular disease, smoking, dyslipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes and prostate cancer treatment including prostatectomy and radiation therapy. ED increases with advancing age, with 22% of men under 40 years affected2–3, compared to 70.2% of men aged 70 years or older4. Diabetic men have increased risk, as they are 3.5 times more likely to develop ED, and do so at an earlier age. The prevalence of ED in diabetics is 52%, but may range as high as 75%5–6. Men who undergo treatment for prostate cancer are also at high risk, with 16–82% of men undergoing prostatectomy developing ED, and 34% and 57% of radiation therapy patients developing ED at 1 and 5.5 years after treatment7–10. Current treatments, including oral therapy with phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (PDE5i) are ineffective in patients with neuropathy, including 16–82% of prostatectomy and 56–59% of diabetic patients7,11–12. Therefore novel therapies are needed that target these difficult to treat patients with CN injury.

When the cavernous nerve is injured, either from surgical insult during prostatectomy, or from peripheral neuropathy that occurs in diabetic and in aging men, the down stream tissue that is innervated by the CN, the corpora cavernosa, undergoes extensive morphological remodeling. The corpora cavernosa is the erectile tissue of the penis. It is riddled by a large number of sinusoidal spaces that fill with blood during an erection, and is composed of abundant smooth muscle, and endothelium, in a matrix of collagen, elastin, and fibroblasts, 13–15. In order for an erection to occur, smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa must relax in response to neurotransmitter signals from the CN16. When the CN becomes damaged, this instigates a cascade of signaling that results in extensive smooth muscle apoptosis, making the smooth muscle of the corpora cavernosa unable to relax in response to the normal neurotransmitter signals, and ED results17–20. The smooth muscle apoptosis is substantial, and has been documented in prostatectomy and diabetic patients to be as high as 50%.21 Apoptosis of primarily penile smooth muscle has been well documented in both ED patients and animal models of CN injury and diabetes18–20. A reduction in penile weight and DNA, accompanies CN injury,18 as does increased collagen, and decreased elastic fibers.22–26 A key regulator of the apoptotic response to loss of innervation is the SHH pathway, and efforts are underway to exploit aspects of its regulation for clinical application.19–20,27–29 However there has been little investigation into the apoptotic cascade that is active in the penis, including caspase signaling mechanisms, and this is a critical avenue for potential intervention to suppress the apoptotic response after CN injury, and thus 75 prevent development of ED.

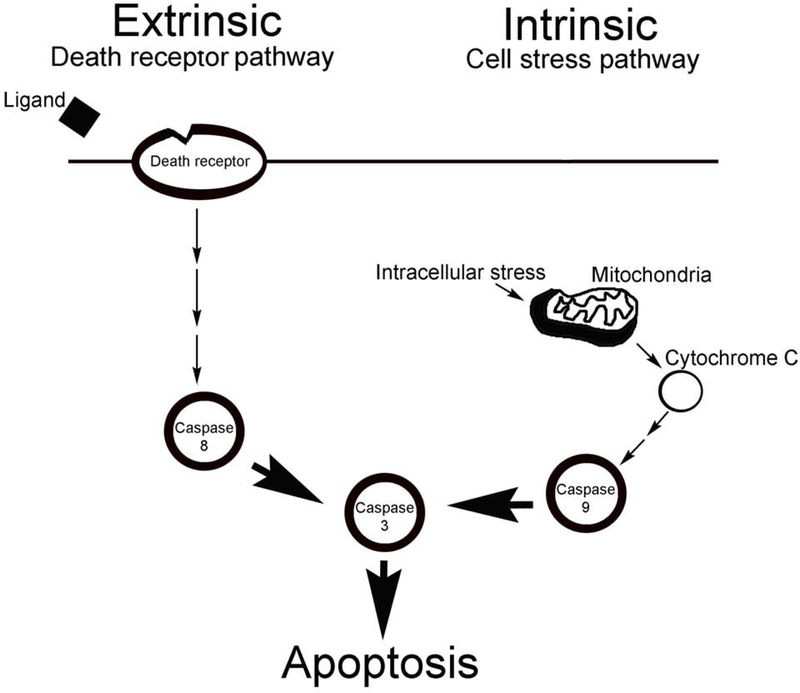

Understanding the mechanism of how apoptosis takes place after CN injury, would be highly useful for therapy development. Apoptosis is governed by a family of evolutionarily conserved cysteine-dependent endoproteases, called caspases, which consist of an amino-terminal domain of variable size followed by large and small catalytic subunits.30 Caspases can be categorized as initiator (Caspase 8, 9, and 10) or effector/execution (Caspase 3, 6, and 7) caspases. The amino-terminal regions of initiator caspases contain a caspase recruitment domain, or death effector domain, that promote their recruitment and activation in multiprotein complexes.31 The process of proximity-induced autoactivation of the caspase zymogen into the active protease is driven by dimerization-induced conformational changes.30 Executioner caspases lack an extended amino-terminal prodomain and require cleavage by initiator caspases for their activation.32 Caspases are activated through two distinct signaling mechanisms; (1) these are the cell-intrinsic pathway (mitochondrial pathway), initiated by internal sensors for severe distress (caspase 9 dependent), and (2) the cell-extrinsic pathway (caspase 8 dependent), triggered by extracellular ligands through cognate death receptors at the surface of target cells (Figure 1).33,31 In the intrinsic pathway, initiator caspase-9 undergoes proximity-induced autoactivation upon its recruitment into the apoptosome, a large caspase-activating complex.34 In the extrinsic pathway, the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex that is assembled at the cytosolic face of several members of the TNF receptor family supports caspase dimerization for activation of caspases 8.32 Once activated by caspase 8 or caspase 9, the executioner caspases are responsible for the characteristic morphological changes of apoptosis.32,35 Whether the intrinsic or extrinsic pathway is the underlying mechanism of how apoptosis occurs in ED patients and in animal CN injury models, is the focus of this work. These studies were performed to determine at what points of the apoptotic pathway that intervention to prevent apoptosis would be useful for therapy development, to prevent the smooth muscle apoptotic response to loss of penile innervation, secondary to prostatectomy or diabetes induced CN injury.

Figure 1:

Diagram of caspase dependent apoptotic mechanism. Caspases are activated through two distinct signaling mechanisms; (1) these are the cell-intrinsic pathway (mitochondrial pathway), initiated by internal sensors for severe distress (caspase 9 dependent), and (2) the cell-extrinsic pathway (caspase 8 dependent), triggered by extracellular ligands through cognate death receptors at the surface of target cells

Materials and Methods

Patients:

Human corpora cavernosal tissue was obtained from 33 patients who were undergoing penile prosthesis implant at Loyola University Medical Center, and at the University of Illinois at Chicago (Table 1). Eleven patients underwent previous prostatectomy surgery, ten patients had diabetes, and twelve patients were treated for Peyronie’s disease, and were considered controls. While Peyronie’s disease affects the tunica of the penis, the corpora cavernosal tissue maintains normal architecture.21 Exclusion criteria included men less than 18 years of age. The Institutional Review Board of Loyola University Medical Center, and the University of Illinois at Chicago, 130 approved the protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Table 1:

Patient information. The average age, time with ED, duration of diabetes, and IIEF score, are presented for Peyronie’s (control), prostatectomy, and diabetic patients.

| Patient group | Age (years) | Duration diabetes (years) | Time with ED (years) | IIEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peyronie’s | 59.9±11.4 | - | 1.8±1.5 | 13.4±8.5 |

| Prostatectomy | 65±8.3 | - | 8.3±7.5 | 3.6±3.1 |

| Diabetes | 61.9±8.1 | 13.8±7.4 | 10.8±5.1 | 5±2.5 |

Specimens for the control Peyronie’s group where taken from men during surgery for Peyronies disease correction in which tutoplast corporoplasties were performed. After gaining signed consent, tissue was obtained from men with Peyronie’s disease sufficiently severe that correction was recommended. Harvest of the corporal tissue was obtained after identification and incision of the tunica near the site(s) of curvature. Once a sufficient corrective corporotomy was made, nearby but un-diseased lacunar tissue, was harvested and immediately placed into fixative or immersed in liquid nitrogen for later study. The control group with Peyronie’s disease were carefully chosen by the self report of rigid erection, and not by their IIEF score, to ensure that the underlying lacunar tissue was as healthy as we could obtain. Men with Peyronie’s disease can have rigid erections that are curved or deformed, which impacts the overall IIEF score.

Animals:

33 adult and nine aged Sprague-Dawley rats postnatal day 115–120 (P115-P120, and P200-P329) were obtained from Charles River. P115–120 Sprague Dawley rats (n=9) that had not undergone surgery, were used as the control group for aged Sprague Dawley rats. Four BB/WOR diabetes prone (diabetic) and four age matched diabetes resistant (control) rats were obtained from an established breeding colony (Biomedical Research Models, Worcester, MA). The presence of diabetes was determined by examining blood glucose levels (Biomedical Research Models). This is a model of type I diabetes in which diabetes onset begins between 60 and 120 days after birth (mean, 96 days) and the rats were euthanized 160–190 days after birth, with approximately 70−−100 days of diabetes expression. Erectile dysfunction of the diabetic rats was previously verified in our laboratory by measuring ICP/BP19 and NOS1–3 protein levels were quantified by western analysis36. The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal care protocol was approved by the Office of Animal Care and Institutional Biosafety at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and animals were cared for in accordance with institutional approval.

Bilateral CN crush and sham surgical procedures:

The pelvic ganglia (PG) and CN were exposed and microforceps (size 0.02 X 0.06mm) were used to crush the CN bilaterally for 30 seconds, more than 5mm from the PG. Crush was performed so that a visible indent in the nerve was apparent, along with a change in color. This method of CN crush has commonly been used in the literature37–38 and the extent and reproducibility of crush injury were previously verified in our laboratory.28 Sham surgery was performed by exposing, but not crushing, the CN (n=6). Rats were euthanized after 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days.

Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC):

IHC was performed on frozen sections that were cut at 12μ, were post fixed in acetone for 15 minutes, and were blocked with 3% milk in PBS for one hour. Sections were incubated over night at 4°C with 1/100 rabbit caspase 3-cleaved (9661s), caspase 9 (9506s), caspase 9-cleaved (9505s) and mouse caspase 8 (9746s), and caspase 8-cleaved (9748s, Cell Signaling). After washing with 1X PBS three times, sections were incubated with the following secondary antibodies, chicken anti-rabbit 594, and goat anti-mouse 594 (1/100, Molecular Probes). IHC was also performed on sections in which the primary antibody was omitted; this was done for all secondary antibodies to ensure non-specific staining was not present. Fluorescent cells were observed using a Leica DM2500 microscope and photographed using a Qicam 1394 digital camera.

Western:

Western analysis was performed as described previously,21 assaying for rabbit caspase 9-cleaved (9505s), mouse caspase 8-cleaved (9748s, Cell Signaling) and mouse β-ACTIN (Sigma). Secondary antibodies were HRP conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (1/35,000, Sigma-Aldrich), and chicken anti-mouse (1/15,000, Santa Cruz). Protein bands were visualized using ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare) and were exposed to Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare). All samples were run in triplicate.

Results

Caspase signaling in penis of prostatectomy, diabetic and Peyronie’s ED patients:

IHC analysis was performed on corpora cavernosal tissue from ED patients with Peyronie’s (control, n=8), diabetes (n=7), and prostatectomy (n=7), assaying for caspase 3-cleaved (active form), caspase 8, caspase 8-cleaved (active form), caspas 9, and caspase 9-cleaved (active form). Caspase 3-cleaved was identified in corpora cavernosa of all three patient groups, but was more abundant in corpora cavernosa from the diabetic and prostatectomy patients, indicating increased apoptosis (Figure 2). Caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved were identified in penis of Peyronie’s patients, and were increased in penis of diabetic and prostatectomy patients, indicating extrinsic apoptotic signaling (Figure 2). Caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were not present in Peyronie’s and prostatectomy patients, and only a few cells were identified that stained positively for caspase 9 in the diabetic group (Figure 2), indicating that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway was not active. The absence of artifact staining was confirmed by omitting the rabbit (bottom left) and mouse (bottom right) primary antibodies (Figure 2). The extrinsic apoptotic pathway was primarily elevated in ED patients

Figure 2:

IHC analysis was performed on corpora cavernosal tissue from ED patients with Peyronie’s (control, n=8), diabetes (n=7), or prostatectomy (n=7), assaying for caspase 3-cleaved (active form), caspase 8, caspase 9, caspase 8-cleaved (active form), and caspase 9-cleaved (active form). Caspase 3-cleaved was identified in corpora cavernosa of all three patient groups, but was more abundant in corpora cavernosa from the diabetic and prostatectomy patients, indicating increased apoptosis. Caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved were identified in penis of Peyronie’s patients, and were increased in penis of diabetic and prostatectomy patients, indicating extrinsic apoptotic signaling. Caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were not present in Peyronie’s and prostatectomy patients, indicating that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway was not active. Only a few cells were identified that stained positively for caspase 9 in the diabetic group. The absence of artifact staining was confirmed by omitting the rabbit (bottom left) and mouse (bottom right) primary antibodies. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

Caspase signaling in penis of a Sprague Dawley rat CN crush injury ED model:

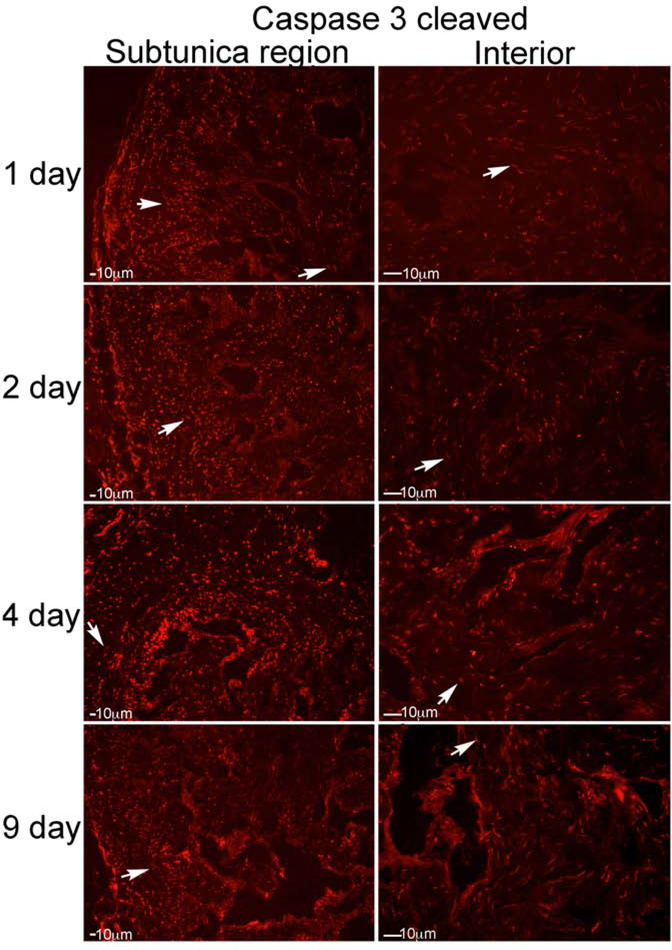

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 3-cleaved, caspase 8, caspase 8-cleaved, caspase 9, and caspase 9-cleaved on penis tissue from Sprague Dawley rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury. Caspase 3-cleaved was increased from 1–9 days after CN injury, indicating apoptosis was taking place (Figure 3). Staining for caspase is subcellular, and appears as small dots in the figures that are highlighted by arrows. Staining was first observed in a discreet subtunica layer, at one day after CN injury (Figure 3). At 2 days after CN injury, caspase 3-cleaved became abundant in the interior of the corpora cavernosa, in smooth muscle between the sinuses (Figure 3). By 4 days after CN injury, staining was abundant both in the subtunica region, in between the sinuses, and within the sinusoidal smooth muscle (Figure 3). By 9 days after injury, staining was decreased, indicating tapering of the apoptotic response (Figure 3). These results suggest a region specific response of the penis to loss of innervation.

Figure 3:

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 3-cleaved, on penis tissue from rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury (Left: subtunica region of corpora cavernosa, Right: interior of corpora cavernosa). Caspase 3-cleaved increased from 1–9 days after CN injury, indicating apoptosis was taking place. Staining was first observed in a discreet layer under the tunica, at one day after CN injury. At 2 days after CN injury, caspase 3-cleaved became abundant in the interior of the corpora cavernosa, in smooth muscle between the sinuses. By 4 days after CN injury, staining was abundant both under the tunica, in between the sinuses, and within the sinusoidal smooth muscle. By 9 days after injury, staining was decreased, indicating tapering of the apoptotic response. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

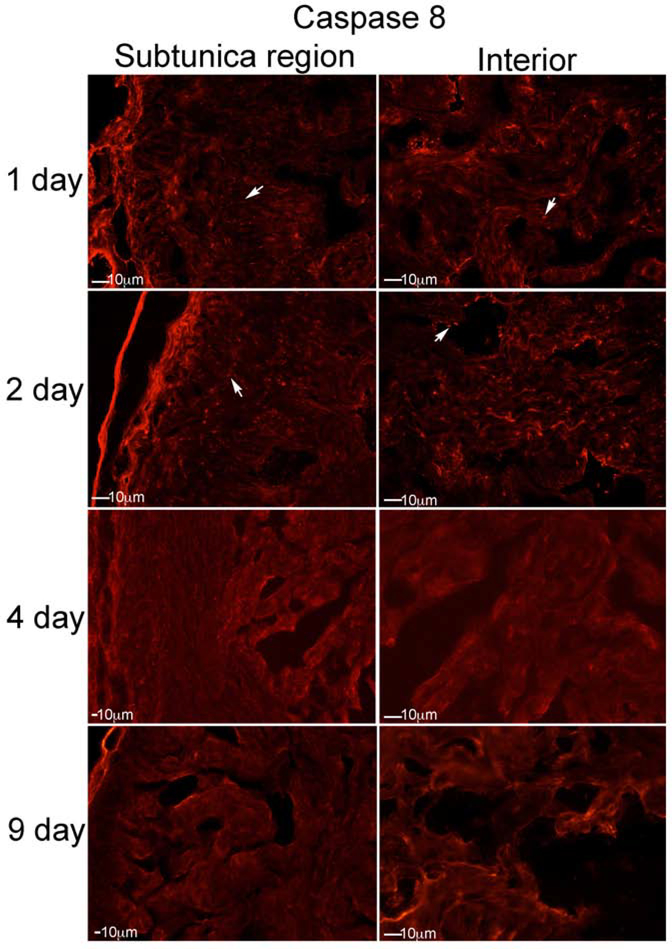

Caspase 8 was identified at low abundance after CN injury in our model. It was observed one day after CN injury, primarily in the subtunica region (Figure 4). Caspase 8 was most abundant at two days after CN injury, and was present both in the subtunica region and within the smooth muscle lining of the sinuses (Figure 4). Caspase 8 was not identified at 4 and 9 days after CN injury (Figure 4). Caspase 8-cleaved was identified at low abundance at 1 and 2 days after CN injury, was barely detectable by 4 days, and was not identified at 9 days after CN injury, indicating only a low, early response of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway in the commonly used rat CN injury model of ED (Figure 5).

Figure 4:

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 8, on penis tissue from rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury (Left: subtunica region of corpora cavernosa, Right: interior of corpora cavernosa). Caspase 8 was identified at low abundance after CN injury. It was observed one day after CN injury, primarily under the tunica. Caspase 8 was most abundant at two days after CN injury, and was present both under the tunica and within the smooth muscle lining of the sinuses. Caspase 8 was not identified at 4 and 9 days after CN injury. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

Figure 5:

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 8 cleaved (active form), on penis tissue from rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury (Left: subtunica region of corpora cavernosa, Right: interior of corpora cavernosa). Caspase 8 cleaved was identified at low abundance at 1 and 2 days after CN injury, was barely detectable by 4 days, and was not identified at 9 days after CN injury. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

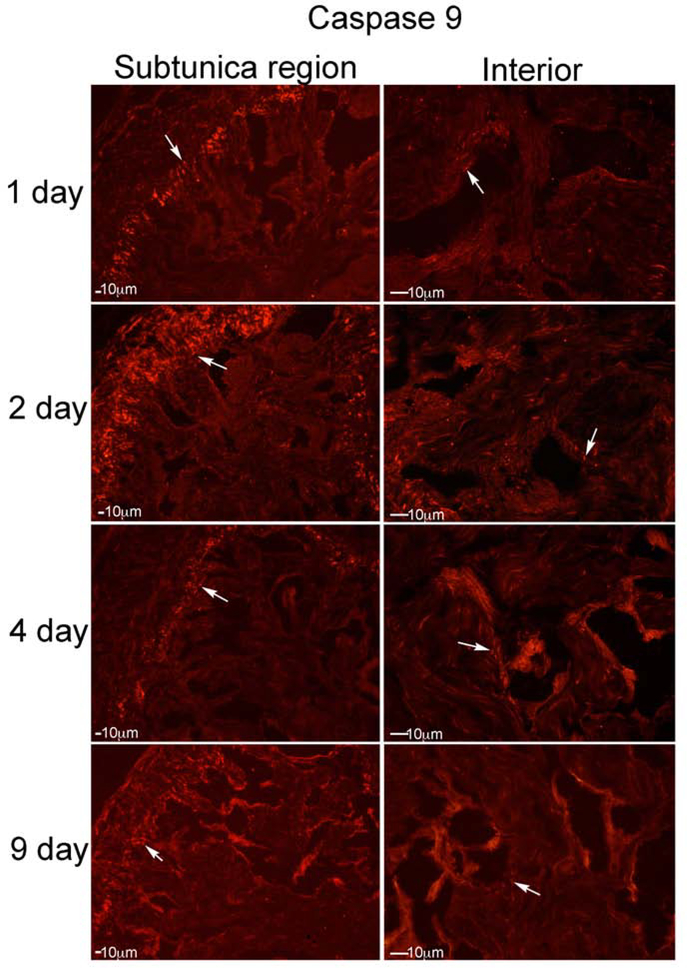

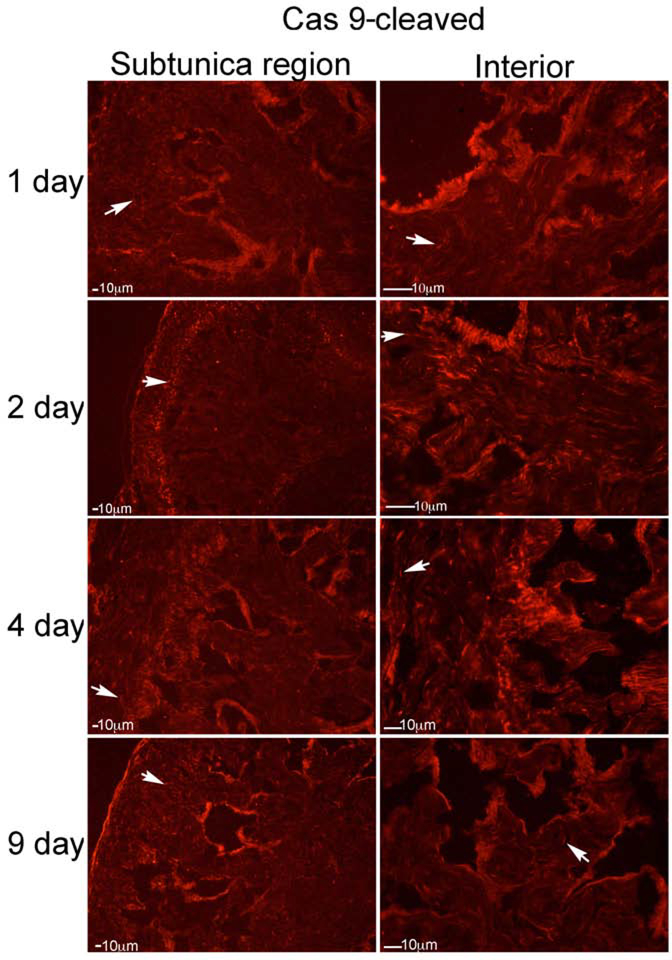

Caspase 9 was abundant in the rat penis after CN injury (Figure 6). It was identified primarily in the subtunica region of the corpora cavernosa at one day after CN injury (Figure 6), with limited staining within sinusoidal smooth muscle (Figure 6). Caspase 9 was most abundant at 2 days after CN injury, started decreasing by 4 days after CN injury, and was present at lower abundance by 9 days after CN injury (Figure 6). Caspase 9-cleaved was also identified in the subtunica region of the corpora cavernosa u at 1–9 days after CN injury, with highest abundance at 2 and 4 days after injury (Figure 7). However caspase 9-cleaved was also abundant in corpora cavernosal tissue between the sinuses, and within the sinusoidal lining (Figure 7), indicating significant intrinsic apoptotic activation in the rat with CN injury.

Figure 6:

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 9, on penis tissue from rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury (Left: subtunica region of corpora cavernosa, Right: interior of corpora cavernosa). Caspase 9 was abundant in the rat penis after CN injury. It was identified primarily in a region under the tunica of the corpora cavernosa at one day after CN injury, with limited staining within sinusoidal smooth muscle. Caspase 9 was most abundant at 2 days after CN injury, started decreasing by 4 days after CN injury, and was present at lower abundance by 9 days after CN injury. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

Figure 7:

IHC analysis was performed assaying for caspase 9-cleaved (active form), on penis tissue from rats that underwent CN crush and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury (Left: subtunica region of corpora cavernosa, Right: interior of corpora cavernosa). Caspase 9-cleaved was identified in the region of the corpora cavernosa under the tunica at 1–9 days after CN injury, with highest abundance at 2 and 4 days after injury. However caspase 9-cleaved was also abundant in corpora cavernosal tissue between the sinuses, and within the sinusoidal lining. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

Western analysis of caspase signaling in ED patients and in a Sprague Dawley rat CN injury model:

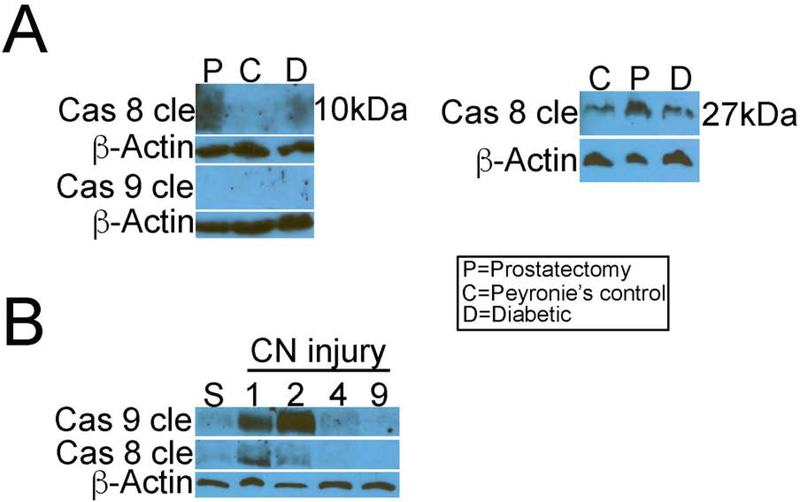

Western analysis for caspase 8-cleaved and caspase 9-cleaved (active form) were performed in corpora cavernosa from ED patients with Peyronie’s (control, n=4), prostatectomy (n=4) and diabetes (n=4). Caspase-8-cleaved was increased with prostatectomy and diabetes in comparison to Peyronie’s controls (Figure 8). Caspase 8 is synthesized as a precursor that is cleaved twice to yield two active fragments, which are shown in the western analysis. β-ACTIN was used as a housekeeper protein for comparison to ensure equal loading of proteins. Caspase 9-cleaved was not identified in human corpora cavernosal tissue (Figure 8).

Figure 8:

(A) Western analysis for caspase 8-cleaved and caspase 9-cleaved (active form) were performed in corpora cavernosa from ED patients with Peyronie’s (control, n=4), prostatectomy (n=4) and diabetes (n=4). Caspase 8 cleaved was increased with prostatectomy and diabetes in comparison to Peyronie’s controls. β-ACTIN was used as a housekeeper protein for comparison to ensure equal loading of proteins. Caspase 9-cleaved was not identified in human corpora cavernosal tissue. (B) Western analysis was performed for caspase 8-cleaved and caspase 9-cleaved in corpora cavernosal tissue from rats that underwent sham or CN crush surgery and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury. Caspase 9-cleaved was detectable at 1 day after CN injury, was most abundant at 2 days after CN injury, and remained identifiable at 4 days after injury. Caspase 8-cleaved was transiently expressed at low abundance at 1 day after CN injury, and was barely detectable by two days after CN injury. Legend: P=Prostatectomy, C=Peyronie’s, D=Diabetic.

Western analysis was also performed for caspase 8-cleaved and caspase 9-cleaved in corpora cavernosal tissue from adult Sprague Dawley rats that underwent sham or CN crush surgery and were euthanized 1 (n=5), 2 (n=5), 4 (n=4) and 9 (n=4) days after CN injury. Caspase 9-cleaved was detectable at 1 day after CN injury, was most abundant at 2 days after CN injury, and remained identifiable at 4 days after injury (Figure 8). Caspase 8-cleaved was transiently expressed at low abundance at 1 day after CN injury, and was barely detectable by two days after CN injury (Figure 8).

Caspase signaling in an aged Sprague Dawley rat model:

IHC analysis was performed for caspase 3-cleaved, caspase 9, caspase 9-cleaved, caspase 8, and caspase 8-cleaved in aged Sprague Dawley rats (P200–329, n=9), that had not undergone surgical CN injury, but 20% of aged Sprague Dawley rats exhibit neuropathy as part of the aging process.39 Uninjured adult rats (P115–120) were examined for comparison (n=9). Caspase 3-cleaved was elevated in aged rat penis in comparison to adult controls (Figure 9), indicating apoptosis was taking place. In a similar manner to what was observed in younger adult rats with CN injury (Figures 6 and 7), caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were increased in aged rat corpora cavernosa (Figure 9). Only a few cells stained for caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved (Figure 9), indicating that intrinsic apoptotic signaling is the main apoptotic mechanism in aged rat penis. Secondary artifact staining was not observed when the primary antibodies were omitted.

Figure 9:

IHC analysis was performed for caspase 3-cleaved, caspase 9, caspase 9-cleaved, caspase 8, and caspase 8-cleaved in aged Sprague Dawley rats (P200–329, n=9) and adult (P115–120, n=9) that had not undergone surgical CN injury. Caspase 3-cleaved was elevated without CN injury in aged rat penis, indicating apoptosis was taking place. Caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were increased in aged rat corpora cavernosa. Only a few cells stained for caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved. Secondary artifact staining was not observed when the primary antibodies were omitted. Arrows indicate staining. 200–400X magnification.

Caspase signaling in BB/WOR diabetic rat model of ED:

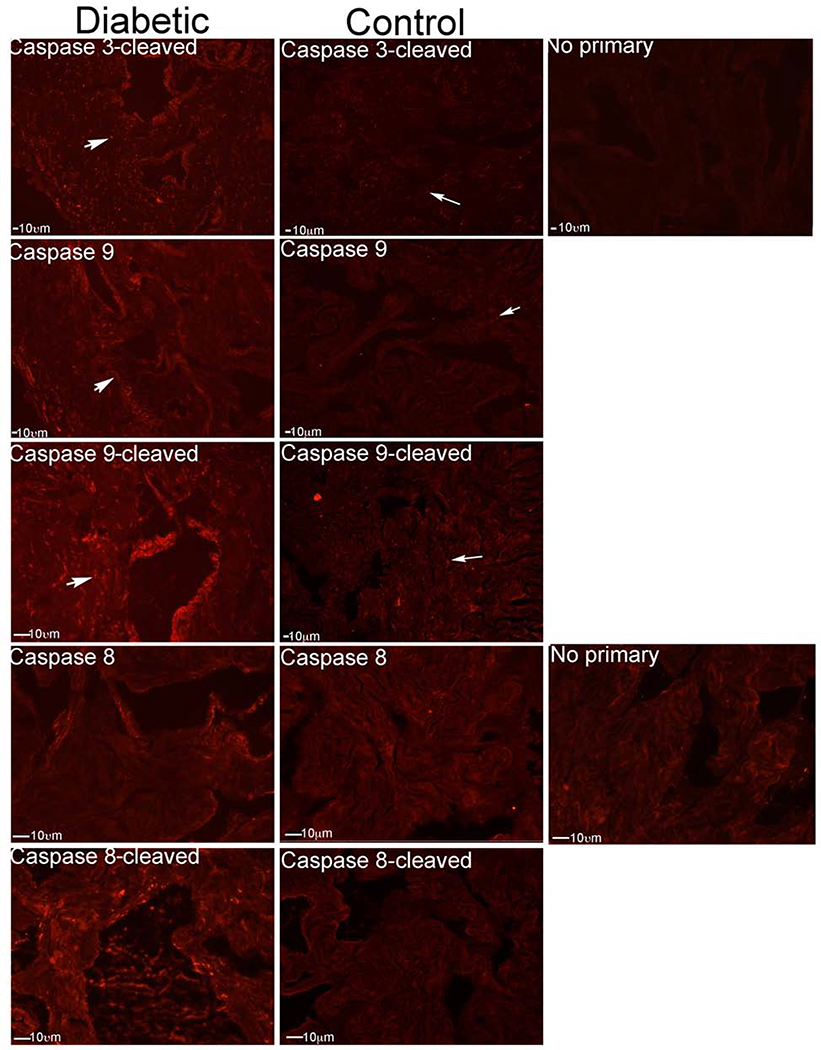

The BB/WOR rat is a naturally occurring mutation that results in a type I model of diabetes that exhibits profound neuropathy, and ED.40 As previously reported, the peak intracavernosal pressure/blood pressure was significantly decreased from an average of 0.91±0.11 in control diabetes resistant BB/WOR rats to 0.57±0.08 in diabetes resistant control penis (p=0.009)19, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase protein was significantly decreased in the pelvic ganglia and CN of diabetic BB/WOR rats in comparison to diabetes resistant controls (19.6 versus 46.7, p=0.036) 36. IHC analysis was performed for caspase 3-cleaved, caspase 9, caspase 9-cleaved, caspase 8, and caspase 8-cleaved in BB/WOR diabetic (n=4) and control (n=4) rat penis. Caspase 3-cleaved was elevated (Figure 9), indicating apoptosis was taking place. Caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were increased in the sinusoidal lining, and around the sinusoids of the corpora cavernosa in the diabetic penis (Figure 10). This is similar to the localization in aged rats (Figure 9). Caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved were also upregulated in a limited manner in the lining of the sinusoids and the tissue in between the sinuses (Figure 10). Previous studies from our group have localized apoptosis primarily to the smooth muscle of this region, and also to the sinusoidal endothelium.19 Controls without primary antibody did not exhibit artifact staining. Diabetic rats exhibit primarily intrinsic apoptotic signaling, but also mild extrinsic pathway activation. Caspase staining is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 10:

IHC analysis was performed for caspase 3-cleaved, caspase 9, caspase 9-cleaved, caspase 8, and caspase 8-cleaved in BB/WOR diabetic (n=) and control diabetes resistant BB/WOR (n=4) rat penis. Caspase 3-cleaved was elevated, indicating apoptosis was taking place. Caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved were increased in the sinusoidal lining, and around the sinusoids of the corpora cavernosa in the diabetic penis. Caspase 8 and caspase 8-cleaved were also upregulated in a limited manner in the lining of the sinusoids and the tissue in between the sinuses. No primary controls did not exhibit artifact staining. Arrows indicate staining. 200X magnification.

Table 2:

Summary of caspase staining. Caspase 3-cleaved, Caspase 8, Caspase8-cleaved, Caspase 9, and Caspase9-cleaved staining in ED patients (Peyronie’s, prostatectomy and diabetic), Sprague Dawley rat after CN injury (1–9 days), adult and aged rats, and BB/WOR control and diabetic rats.

| Cas3-cle | Cas 8 | Cas8-cle | Cas 9 | Cas9-cle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | |||||

| Peyronie’s | + | + | + | − | − |

| Prostatectomy | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| Diabetes | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Rat CN injury | |||||

| 1 day | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| 2 day | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| 4 day | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ |

| 9 day | + | − | − | + | + |

| Rat age | |||||

| Adult control | − | − | − | − | − |

| Aged adult | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ |

| Rat diabetes | |||||

| BB/WOR control | − | − | − | − | − |

| BB/WOR diabetic | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

Low level staining

High level staining

Little to no staining

Discussion

A consistent finding in studies of corpora cavernosal tissue in ED patients is that the remodeling of the corpora cavernosa, including smooth muscle apoptosis and deposition of collagen, making the tissue unable to respond to normal neurotransmitter signals and causing ED, continues over an extended period of time after onset of diabetes, and after prostatectomy. The tissue we assayed was from patients that were an average of 13.8 years post diabetes onset and 8.3 years post prostatectomy, indicating that the remodeling process is an on going phenomenon. In the most commonly used rat CN crush and resection models, there is an initial large surge of apoptosis in the first week after injury, followed by a low level response that continues over an extended period.18,20,41 If this initial apoptotic response can be suppressed, then smooth muscle and erectile function are preserved,20,29 and efforts for clinical intervention would be most effective to target this initial response and preserve as much smooth muscle as possible to maintain erectile function. It is known that the CN is injured during prostatectomy surgery and with peripheral neuropathy during diabetes, and it is assumed that there is a similar initial surge in apoptosis, followed by a longer, low level remodeling process, as observed in our animal models. This is supported by documented decease of penile smooth muscle, by as much as 50%, in prostatectomy and diabetic ED patients.21 However in the first few weeks after prostatectomy and onset of diabetes, it is not ethically possible to acquire human corpora cavernosal tissue to verify the initial response. Corpora cavernosal tissue can only be assayed in patients when the remodeling is already substantial enough to warrant prosthesis implant in the treatment of ED. However the ongoing remodeling that occurs in ED patients, provides ample opportunity for intervention and prevention, particularly if intervention occurs early prior to substantial smooth muscle loss.

Knowing how and when to intervene to prevent the apoptotic response most effectively, is critical for development of drugs to prevent ED, morphological remodeling of the corpora cavernosa, and thus disease management. In this study we’ve shown that apoptosis takes place in ED patients, primarily through a caspase 8 (extrinsic) apoptotic mechanism. The exception being a subset of diabetic patients in which significant caspase 9 (intrinsic) apoptosis was observed in addition to extrinsic activation. So the apoptotic response of prostatectomy and diabetic ED patients, is similar in most patients, but is not identical. It is unclear why only a subset of the diabetic patients exhibit the caspase 9 response, and further investigation is required to delineate any other underlying contributing factors. In the most commonly used rat CN injury model of ED, the primary pathway of apoptosis activation is caspase 9 dependent (intrinsic). However there is an initial, short, low level flux through the caspase 8 apoptotic mechanism, primarily on day one, but to a lower level on day two after CN injury. It is important to keep in mind when developing interventions to prevent ED that our animal models may diverge from the signaling mechanisms observed in humans, and this must be taken into account when considering therapy development and testing of drugs for preventing ED. While the rat utilizes primarily caspase 9 apoptotic mechanisms, there is significant flux through caspase 8 early on, thus making it a reasonable model for development of preventative strategies, as long as the time frame of apoptotic response after CN injury is considered.

It is possible that utilization of both apoptotic pathways in the rat may reflect apoptosis of specific cell types in the penis. In our animal models, there is a defined sequence of apoptotic events, which are tied to specific localizations within the penile tissue. Apoptosis appears most abundant initially in a concise, subtunica region. This is a proliferative layer, which primarily consists of fibroblasts and smooth muscle. After a day or two, apoptosis localization shifts to the more interior region of the corpora cavernosa, including smooth muscle and fibroblasts between the sinusoids, and within the smooth muscle lining of the sinuses. We have observed this same pattern repeatedly in response to CN injury in our crush and resection prostatectomy models. It is unclear if a similar pattern of apoptosis localization is present in ED patients since similar tissue acquisition in the early time frame after injury, is not possible with ED patients.

A similar trend in apoptosis localization was not observed in aged and diabetic rats that did not under go surgical nerve injury. In our aged Sprague Dawley rat model, in which the rats were 200 to 329 days old, a fair amount of apoptosis occurred without surgical insult, as evidenced by caspase 3-cleaved staining. Staining was evenly distributed in the region under the subtunica region, between the sinuses, and within the sinusoidal lining, suggesting the concise localization viewed in younger adult rats (P120) is in direct response to surgical nerve injury. Our previous studies localize the apoptosis to primarily penile smooth muscle in these areas.19–20 Similar to younger adult rats (P120), caspase 9 apoptotic mechanisms were the primary means of apoptosis, with caspase 9 and caspase 9-cleaved being abundant in the aged corpora cavernosa, particularly within the sinusoidal lining. Very low-level caspase 8 was observed in the aged rats. About 20% of Sprague Dawley rats exhibit neuropathy with aging, presumably as part of the aging process.38 Previously apoptosis was attributed to the loss of innervation that occurs with age. However the distribution of apoptosis suggests that with aging the loss of smooth muscle is more homogenous within the corpora cavernosa, and may reflect a more complex mechanism, or more advanced CN injury from naturally deriving peripheral neuropathy.

Conclusions

Apoptosis takes place primarily through the extrinsic caspase 8 dependent pathway in ED patients, and via the intrinsic caspase 9 dependent pathway in the commonly used CN crush, aging and diabetic rat models of ED. Knowing how and when to intervene to prevent the apoptotic response most effectively, is critical for development of drugs to prevent ED. Animal models may diverge from the signaling mechanisms observed in ED patients. While the rat utilizes primarily caspase 9, there is significant flux through caspase 8 early on after CN injury, making this a reasonable model, as long as the timing of apoptosis is considered after CN injury. The BB/WOR diabetic rat also exhibits significant extrinsic activation, and parallels the human condition with activation of both apoptotic mechanisms. This is an important consideration for study design and interpretation, must be taken into account for therapy development and testing of drugs, and our therapeutic targets should ideally inhibit both apoptotic mechanisms.

Statement of Significance:

Apoptosis takes place primarily through the extrinsic caspase 8 dependent pathway in ED patients, and via the intrinsic caspase 9 dependent pathway in commonly used CN crush ED models; Knowing how and when to intervene to prevent the apoptotic response most effectively, is critical for development of drugs to prevent ED, morphological remodeling of the corpora cavernosa, and thus disease management.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH/NIDDK Award number R01DK101536.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol 1994; 151: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heruti R, Shochat T, Tekes-Manova D, Ashkenazi I, Justo D (2004) Prevalence of erectile dysfunction among young adults: results of a large-scale 525 survey. J Sex Med 2004; 1: 284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen HMT, Gabrielson AT, Hellstrom WJG. Erectile dysfunction in young men-A review of the prevalence and risk factors. Sex Med Rev 2017; 5: 508–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. American J Medicine 2007; 120: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim LS, Goldstein I. Diabetic sexual dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1996; 25:379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouidrat Y, Pizzol D, Cosco T, Thompson T, Carnaghi M, Bertoldo A, Solmi M, Stubbs B, Veronese N. High prevalence of erectile dysfunction in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies. Diabetic Medicine 2017; 34: 1185–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendirci M, Hellstrom WJ (2004) Current concepts in the management of erectile dysfunction in men with prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer 3: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnick MJ, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368(5):436–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson E, et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2011; 12:891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanu JC, Avildsen IK, Nelson CJ. Erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: prevalence, medical treatments, and psychosocial interventions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016; 10: 102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perimenis P, Markou S, Gyftopoulos K, Athanasopoulos A, Giannitsas K, Barbalias G. Switching from long-term treatment with self-injections to oral sildenafil in diabetic patients with severe erectile dysfunction. European Urology 2002; 41: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Lopez DS, Chen M, Wang R. Penile rehabilitation therapy following radical prostatectomy: A meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2017; 14: 1496–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams-Ashman HG. Enigmatic features of penile development and functions. Perspect Biol Med 1990; 33: 335–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeson TS, Leeson CR. The fine structure of cavernous tissue in the adult rat penis. Invest Urol 1965; 3: 144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podlasek CA, Meroz CL, Korolis H, Tang Y, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2005; 11: 4011–4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett AL, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, Chang TS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science 1992; 257: 401–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein LT, Miller MI, Buttyan R, Raffo AJ, Burchard M, Dervis G., et al. Apoptosis in the rat penis after penile denervation. J Urol 1997; 158: 626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.User HM, Hairston JH, Zelner DJ, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Penile weight and cell subtype specific changes in a post-radical prostatectomy model of erectile dysfunction. J Urol 2003; 169: 1175–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podlasek CA, Zelner DJ, Harris JD, Meroz CL, Tang Y, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Altered sonic hedgehog signaling is associated with morphological abnormalities in the penis of the BB/WOR diabetic rat. Biology of Reproduction 2003; 69: 816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podlasek CA, Meroz CL, Tang Y, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Regulation of cavernous nerve injury-induced apoptosis by sonic hedgehog. Biol Reprod 2007; 76: 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angeloni NL, Bond CW, McVary KT, Podlasek CA. Sonic hedgehog protein is decreased and penile morphology is altered in prostatectomy and diabetic patients. PLOS ONE 2013; 8: e70985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacono F, Giannella R, Somma P, Manno G, Fussco F, Mirone V. Histological alterations in cavernous tissue after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2005; 173:1673–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atilgan D, Parlaktas BS, Uluocak N, Erdemir F, Markoc F, Saylan O, Erkorkmaz U. The effects of trimetazidine and sildenafil on bilateral cavernosal nerve injury induced oxidative damage and cavernosal fibrosis in rats. Sci World J 2014; 970363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrer JE, Velez JD, Herrera AM. Age-related morphological changes in smooth muscle and collagen content in human corpus cavernosum. J Sex Med 2010; 7: 2723–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klimachev VV, Neimark AI, Gerval’d V, Bobrov IP, Avdalian AM, Muzalevskaia NI, Geral’d IV, Aliev RT, Cherdantseva TM. Age changes of the connective tissue structures of human penis. Morfologiia 2011; 140: 42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choe S, Veliceasa D, Bond CW, Harrington DA, Stupp SI, McVary KT, Podlasek CA. Sonic hedgehog delivery from self-assembled nanofiber hydrogels reduces the fibrotic response in models of erectile dysfunction. Acta Biomateralia 2016; 32: 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bond CW, Angeloni NL, Harrington DA, Stupp SI, McKenna KE, Podlasek CA. Peptide amphiphile nanofiber delivery of sonic hedgehog protein to reduce smooth muscle apoptosis in the penis after cavernous nerve resection. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angeloni NL, Bond CW, Tang Y, Harrington DA, Zhang S, Stupp SI, McKenna KE, Podlasek CA. Regeneration of the cavernous nerve by Sonic hedgehog using aligned peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Biomaterials 2011; 32: 1091–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choe S, Kalmanek E, Bond C, Harrington D, Stupp SI, McVary KT, Podlasek CA. Optimization of sonic hedgehog delivery to the penis from self-assembling nanofiber hydrogels to preserve penile morphology after cavernous nerve injury. Nanomedicine 2019; 20: 102033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamkanfi M, Deciercq W, Kalai M, Saelens X, Vandenabeele P. Alice in caspase land. A phylogenetic analysis of caspases from worm to man. Cell Death Differ 2002; 9: 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan T-J, Han L-H, Cong R-S, Liang J. Caspase family proteases and apoptosis. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 2005; 37: 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramirez MLG, and Salvesen GS. A primer on caspase mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2018; 82: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair P, Lu M, Petersen S, Ashkenazi A. Apoptosis initiation through the cell-extrinsic pathway. Methods in Enzymology 2014; 544: 99–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorstyn L, Akey CW, Kumar S. New insights into apoptosome structure and function. Cell Death Differ 2018; 25: 1194–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opdenbosch NV, and Lamkanfi M. Caspases in cell death, inflammation, and disease. Immunity 2019; 50: 1352–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podlasek CA, Zelner D, Bervig TR, Gonzalez CM, McKenna KE, McVary KT. Characterization and localization of NOS isoforms in BB/WOR diabetic rat. Journal of Urology 2001; 166: 746–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullerad M, Donohue JF, Li PS, Scardino PT, Mulhall JP. Functional Sequelae of Cavernous Nerve Injury in the Rat: is There Model Dependency. J Sex Med 2006; 3: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nangle MR, Keast JR. Reduced Efficacy of Nitrergic Neurotransmission Exacerbates Erectile Dysfunction After Penile Nerve Injury Despite Axonal Regeneration. Exp Neurol 2007; 207: 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podlasek CA. 2016. Animal models for the study of erectile function and dysfunction. In: Kohler TS, and McVary KT (ed). Contemporary treatment of erectile dysfunction: A clinical guide, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer. ISBN: 978–3-319–31585-0 [Google Scholar]

- 40.McVary KT, Rathnau CH, McKenna KE. Sexual dysfunction in the diabetic BB/WOR rat: a role of central neuropathy. Am J Physiol 1997; 272: R259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angeloni N, Bond CW, Harrington D, Stupp S, Podlasek CA. Sonic hedgehog is neuroprotective in the cavernous nerve with crush injury. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 1240–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]