Abstract

Objectives:

To understand healthcare team perceptions of the role of professional interpreters and interpretation modalities during end of life and critical illness discussions with patients and families who have limited English proficiency in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Methods:

We did a secondary analysis of data from a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews of 16 physicians, 12 nurses, and 12 professional interpreters from 3 ICUs at Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

Results:

We identified 3 main role descriptions for professional interpreters: 1) Verbatim interpretation; interpreters use literal interpretation; 2) Health Literacy Guardian; interpreters integrate advocacy into their role; 3) Cultural Brokers; interpreters transmit information incorporating cultural nuances. Clinicians expressed advantages and disadvantages of different interpretation modalities on the professional interpreter’s role in the ICU.

Conclusion:

Our study illuminates different professional interpreters’ roles. Furthermore, we describe the perceived relationship between interpretation modalities and the interpreter’s roles and influence on communication dynamics in the ICU for patients with LEP.

Practice implications:

Patients benefit from having an interpreter, who can function as a cultural broker or literacy guardian during communication in the ICU setting where care is especially complex, good communication is vital, and decision making is challenging.

Keywords: Critical care, Critical illness, Limited English proficiency, Patient care team, Patient care, Interpreter, End-of-life, Decision making, Interpreter modality, Interpreter mode

1. Introduction

Globally, immigration has risen in recent years, resulting in increasing numbers of patients experiencing language barriers in the healthcare systems within their destination countries.[1-9] Language barriers are a leading cause of health disparities.[10-15] and negative health outcomes as well as decreased patient satisfaction.[16-26]

In the United States, over 25 million people have limited English proficiency (LEP) and that number continues to increase.[27] Research in the US has demonstrated that professional interpreters in healthcare can reduce language barriers, improve patient-clinician interactions, and also provide emotional support to patients and families.[28, 29] Interpretation over time has been perceived as a “simple one-to-one machine-like process”,[30] however the literature highlights the importance of interpreters as part of the clinical team to overcome health disparities and improve the quality of care for patients with LEP.[31-36] When interpreters are involved, communication errors decrease, and cultural awareness, patient understanding as well as satisfaction with communication increase.[37-39] As well as benefitting patients, interpretation also offers clinical teams the opportunity to expand their knowledge and understanding of a range of cultural and social perspectives.[40] The literature characterizes interpreters as communication support, interlocutors, information providers, mediators, finally creators of safe environments for patients.[35, 41-46] In practice, professional interpreters are not always neutral and they may actively contribute as co-constructors during clinical interactions.[41, 47]

Alternative interpreting modalities may be used in situations when in-person professional interpreters are not available. These modalities include videoconference, telephone interpreters, family members, and bilingual staff who may be used to “get by”. [48-52] There is overwhelming evidence that in-person professional interpreters are the preferred and recommended choice, however many studies indicate that they are underutilized in practice.[6, 21, 37, 38, 53-64]

Communication and decision making may be one of the most important components of ICU clinical practice.[65] Ideally decision making should be a collaborative endeavor in the ICU setting but often it is not.[66]

ICU patients are usually too ill or sedated to express actively their treatment preferences and values, therefore, family members play an important role in decision making in the ICU setting.[67] Even among those with language proficiency studies have shown that physician-family communication in the ICU was complicated and often incomplete. Language barriers magnify this issue further.[68]

Previous research conducted in the ICU setting describes differences in care for ICU patients who have LEP.[69, 70] A study done by Zurca et al. about communication with families with LEP in the pediatric intensive care unit, described how having a professional interpreter during rounds helped families understand the information provided.[71] Although studies showed the benefits of professional interpreters, some studies done in the ICU setting have shown that despite professional interpreters, content alterations during interpretation occur and have consequences such as miscommunication during family conferences, as well as reduced emotional support and information exchange.[72, 73] These studies did not consider the positive aspects of interpretation alterations that may enhance communication with LEP patients in the ICU setting, and potential alternative approaches to the role of professional interpreters.

There is a gap in the literature exploring different interpreter roles and contributions within the ICU setting and during end of life discussions with patients and families with LEP.

The objective of this study was to understand the perspectives of ICU physicians and nurses as well as interpreters about what they viewed as the professional interpreter’s role during end of life and critical illness discussions with patients and families who have LEP in the ICU. Furthermore we gathered physicians’, nurses’, and interpreters’ perceptions about the advantages and disadvantages of diverse interpretation modalities on the interpreter’s role when communicating with patients and families who have LEP in the ICU.

2. Methods:

2.1. Study Design

Using methodology guided by grounded theory, we conducted a secondary analysis of semi-structured interviews of interpreters, ICU bedside nurses, and ICU physicians, who initially described their perceptions about the factors that influence decision making about end of life for patients and family members with limited English proficiency in the ICU.[74] The findings are reported in accordance with the COREQ guidelines.[75]

The study was implemented at a single center tertiary care hospital. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and oral consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Participants

As described elsewhere,[74] interpreters included were adults (≥ 18 years) who reported working in a general medical or surgical ICU. We did purposive sampling to recruit participants. We used email distribution lists to invite participants to participate in the study (113 physicians, 195 nurses, and 65 interpreters were contacted via email). We enrolled 16 physicians, 12 nurses and 12 interpreters. The 40 people are all those who responded affirmatively to the email sequentially within their professional group. We had more than 40 people respond to the email looking for participants. We did not record the exact number of positive responses to our invitations, although we estimate the number was 45-50. There were no recruitment difficulties and we cancelled scheduled interviews after thematic saturation was achieved.

2.3. Data Collection

The interview guide was developed by a multidisciplinary team (AKB, CJ, and MW) based on literature review, expert opinion, and clinical experience. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions and was pilot tested with the assistance of a qualitative researcher who was not directly involved with the study (Appendix 1). Between November 2017 and April 2018, members of the study team (AKB, CAN, CJ) conducted one-on-one, in-person, semi-structured interviews which lasted approximately 15 minutes with nurses to over 60 minutes with some interpreters and physicians. We audio recorded the interviews, transcribed them verbatim, and the resulting transcripts were anonymized. Data collection ceased once we reached data saturation, and no new themes were emerging based on our original interview questions.[76]

2.4. Qualitative analysis

For our first cycle of coding, we used line by line descriptive coding. The interview guide questions were not originally formulated to describe or explore the interpreter's role however this rich theme became evident during our initial coding procedures. After we identified the interpreter’s roles description, we proceed with secondary axial coding, as part of grounded theory (Codebook Appendix 2) complemented with an exploratory coding method called hypothesis coding to further understand the interpreter role and interpretation modalities (Appendix 3).[74, 77] During that phase two, study team members (MUS, NES) coded in duplicate and met to reach consensus on each interview.

After the first cycle of coding was complete, we initiated our second cycle of coding, using axial coding we linked categories and subcategories in order to find relationships between the interpreter role and interpreting modalities.[77] Two study team members (NES, MUS) met to examine the codes looking for tendencies and patterns using memory cards and mapping analysis.[78] We were also guided during analysis by the framework of barriers to end-of-life decision making and care for patients with LEP obtained from previous qualitative work done.[74] Following these phases, the researchers (MUS, NES) developed overarching themes and selected representative quotes. Two other researchers (AKB, MW) reviewed the themes to guarantee reliability and credibility; using triangulation through multiple analysts.[79] We utilized NVivo software Version 11 (QSR Intl Inc; Burlington, MA) to manage and analyze data. We did not do formal member checking.

3. Results:

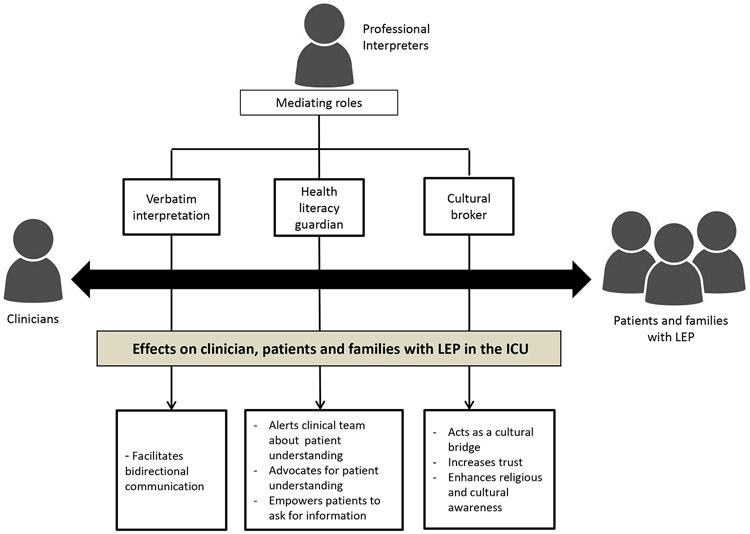

A total of 40 interviews were conducted. Participants’ baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. We identified two themes to describe the views of the interpretation during end of life and critical illness discussions with patients and families who have LEP in the ICU: First, we describe three main roles for the interpreter (Table 2): Verbatim interpretation, Health literacy guardianship, and Cultural brokerage. Second, we present two sub-themes of interpretation modalities (Table 3): Advantages and disadvantages. We describe how different interpretation modalities relate to the interpreter’s roles and influence communication dynamics with patients and families who have LEP in the ICU. Figure 1 illustrates our first theme representing how professional interpreters’ roles mediate effects on clinicians, as well as patients and families with LEP. Appendix 4 represents the frequency in which respondents (physicians, nurses, professional interpreters) associated with themes and sub-themes to describe different disciplinary/role/modalities perspectives.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Interpreter (N=12) |

Nurse (N=12) | Physician (N=16) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 10 (83) | 11 (92) | 5 (31) |

| Age Range | 30-65 | 20-35 | 30-65 |

| Nationality | |||

| US born, n (%) | 1 (8) | 12 (100) | 9 (56) |

| Languages Interpreted | NA | NA | |

| Spanish | 5 (42) | NA | NA |

| Somali | 1 (8) | NA | NA |

| Arabic | 3 (25) | NA | NA |

| Mandarin Chinese | 1 (8) | NA | NA |

| Lao | 1(8) | NA | NA |

| Hmong | 1 (8) | NA | NA |

| Time in ICU practice or working as interpreter | 2-20 years | 2 months-11 Years | 4-30 years |

Table 2.

Interpreter Role

| Interpreter Role | Quote |

|---|---|

| Verbatim interpretation | |

| Role definition | 2.1."As a medical interpreter, we just basically interpret everything the provider says [or what] the patient or the family says. We’re not supposed to provide any personal opinion." (Interpreter) 2.2."We’re not supposed to say anything regarding any of the medical appointments or provide any opinions or advice." (Interpreter) 2.3. "We can do is all basically just facilitate the communication. There are lots of things we cannot do [explain and give advice], but we actually are the front line to interact with the patient and providers." (Interpreter) 2.4. "We don’t want to make the patient make the decision, because that’s not my job." (Interpreter) |

| Role conflict/dilemma | 2.5."[As interpreters], we can probably [be] more helpful than we are now. But [with] our job limitations, we cannot say or do anything besides interpretation. That’s one thing that’s a dilemma for us." (Interpreter) 2.6."Our rules as interpreters [are] very strict … You have to translate the message in English … In very rare cases, we have to advise or to say something more. [and we should be able to say more if needed]." (Interpreter) 2.7. “Then you just feel really, really difficult, because, on one hand, you want to help [the patient and family], but on the other hand, you’re not supposed to.” (Interpreter) |

| Clinical team perspectives | 2.8. "[When interpreters adapt the interpretation], I try to clarify … by saying [to the interpreter] it’s okay to just translate [exactly what the patient is saying] rather than adding something from [your] perspective--which taints things in terms of what the patient or their family might be wanting to say … Most of our in-person interpreters do a very good job of repeating exactly what you’re saying." (Physician) 2.9. "[Sometimes patients and interpreters] might start having a conversation on their own … Then I start wondering what’s going on there because [the interpreters and patients] shouldn’t be doing that." (Physician) 2.10. "The translator might automatically be simplifying, or the translator might automatically be condensing what they say [to the patient] into 'medicalese'--and I don’t know what—how much the translator is altering the sophistication of [the patient's] language". (Physician) |

| Health literacy guardian | |

| Role definition | 2.11. "If I have information [patient related] maybe affecting a decision or the diagnosis or maybe in the benefit of the patient, absolutely I step up and say [to the clinical team], “Please, I have something to say.” (Interpreter) 2.12. "They’ll [interpreter] pull you [physician] aside and they’ll alert you about any family member who might be driving the conversation, who might not be as astute or sophisticated." (Physician) 2.13. "If you see there’s some cultural barrier or communication barrier, that you thought the provider and the patient had some misunderstanding with each other—yes, then that’s our interpreter’s job to intervene. Intervening—we’re not supposed to do too often—just when really, really necessary.” (Interpreter) |

| Clinical team and interpreter perspectives | 2.14. "The interpreter should be empowered to intervene if they notice there’s something wrong (with understanding)." (Physician) 2.15. “We… have to empower [patients and families] to really ask what they don’t understand and really help them communicate so they have a better understanding of what’s going on.” (Interpreter) 2.16. “When I see that patients really want an interpreter and they’re not getting one, [I] at least try to advocate for that right for them to be able to communicate their needs." (Interpreter) 2.17. "I [physician] want to say I think that the interpreters here do a very good job of advocating for patients.” (Physician) 2.18. "As the interpreter, since we know what this patient’s … difficulty will be … sometimes we suggest that the provider, 'Can you please write down the name [of the medication], the dose, how to take that?” (Interpreter) 2.19. “We have to explain the provider and say, “Hey, at this time right now, the patient doesn’t understand exactly what is going on.” (Interpreter) |

| Cultural Broker | |

| Role definition | 2.20. "I understood my role here—to facilitate communication between the patient, the family, and the providers… taking in consideration our cultures, habits, and everything." (Interpreter) |

| Clinical team and interpreter perspectives | 2.21. “An interpreter usually understands both cultures [patients and clinical team] and tries to translate the cultural differences.” (Physician) 2.22. "If we [identify that] .… or sense something could be a misunderstanding for cultural reasons, [we] try to get the provider or patient to identify that and get on the same page.” (Interpreter) 2.23. “[Beyond the role of interpreting is the role of] cultural ambassador to the patient—somebody who knows not just the language, but could give you some insight into some of the cultural reasons." (Physician) |

| Trust builder | 2.24. “For [patients and families, the interpreter] is a familiar face, in a sense—someone who [patients and families] can connect with better than they can connect with someone who doesn’t speak their language.” (Nurse) |

Table 3.

Interpretation modality

| Modality | Modality advantages |

|---|---|

| In-person | 3.1. “… So my experience tells me that this [Interpretation] is best done face-to-face, best done with an interpreter who understand the cultural norms for that particular group, and the interpreter can oftentimes give cues to the team or providers, things to establish this relationship, which is the cornerstone for effective care”. (Physician) 3.2. …“Because, oftentimes, they [Interpreters] have cultural understandings that I don’t know. Then sometimes then they’ll ask me, “I’d like to say this to the family. Does this make sense to you?” and so it can be a little bit—not just a direct translation, but also help with cultural interpretation”. (Physician) 3.3. “It would be nice to actually have a relationship with an interpreter … I think having an in-person interpreter and having the cultural background would probably be the best”. (Nurse) 3.4. “I think the in-person interpreter for them [patients and families with LEP], it’s a familiar face. Someone who they can connect with better than they can connect with someone who doesn’t speak their language or understand their culture”. (Nurse) 3.5. “Only certain interpreters can be there during that time [end of life conversations]. It will give great support for the doctors, for the nurses, for the family, that bridge for everyone. You really have to have that cultural expert”. (Interpreter) 3.6 “You [healthcare team] have the interpreter here, and then you have the cultural broker, who is an interpreter, but plays more at a cultural”. (Interpreter) 3.7. “I’ve been seeing that the in-person interpreter is better than the iPad interpreter. Cuz this person can translate sometimes the emotions of the family, and also can resurrect any doubts, concerns or anything that probably being an English speaker we could not understand. I think that’s helpful”. (Physician) 3.8 “I know when we got an in-person interpreter, things got better as far as understanding, especially the family understanding a little bit more what was going on”. (Nurse) |

| Videoconferencing interpretation | 3.9. “With the iPad, really they’re available 24/7. It’s much easier to use for interpretation. I do find myself using it all the time. Does that still impair communication? I’m sure it does”. (Physician) 3.10. “I would say in the past, waiting for the interpreter was not very easy. Now, we have a tool for communication and interpretation [iPad] at our disposal that we should not even think about not using it”. (Physician) 3.11. “I mean it’s been a lot more helpful having the iPad interpreter, because its pretty much 24/7, for the most part, for most of the languages anyway that we see up here”. (Nurse) |

| Family members | 3.12. “We [Healthcare team] are often – maybe even overly – reliant on that family member to either translate for the patient or to communicate what they believe the patient’s wishes would be. I think oftentimes for convenience sake, unfortunately, and for time sake, we utilize those family members”. (Physician) 3.13. “There are some advantages to using family because they have insight into the patient and culture. The disadvantage is that sometimes you’re getting their filtered view and not the parent, or whatever, the family member’s view. (Physician) 3.14. “I think they [Patients and families with LEP] engage the best when there’s actually a family member there to be the arbiter back and forth to the patient. Because like I’ve said before, some of the personal issues and nuances can get lost in the translation because the patient is speaking with somebody who is a stranger to them”. (Nurse) |

| Modality | Modality disadvantages |

| In-person | 3.15. “I will always use an interpreter if I can for [verbatim] interpretation. Or an iPad interpreter or the phone, or something. Realistically, we use family more than I wish we did, because sometimes it’s the middle of the night, or sometimes you’re popping into the room for five minutes and you’ve got 15 other patients to see. You don’t have time to wait for an interpreter to be paged and to come. (Physician) 3.16. “I think that we need more availability of in-person interpreters. In-person interpreter’s availability for interpretation… I find it very difficult”. (Physician) 3.17. “I’ve found in the past that the interpreter can—the in-person interpreter can be hard to get a hold of and be frequently late. They’re hard to schedule correctly for interpretation. (Nurse) |

| Videoconferencing interpretation | 3.18. “The in-person interpreters, I think, generally do a better job interpreting than the iPad interpreters, particularly with the fact that the ICU is noisy, a lot of background noise, oxygen, et cetera”. (Physician) 3.19. “Sometimes, of course, you [Healthcare team] have to use the iPad for translation, which still works way better than the phone, but still, they’re [Interpreters] not in the room. They’re not sensing maybe the tension or the lack of tension or understanding the dynamics”. (Physician) 3.20. “Especially if we [Healthcare team] have the iPad interpreter we can always use, but they’re not always the kind of cultural interpreter that might be necessary”. (Nurse) 3.21. “The availability of interpreters is beneficial. If we could have more and have them more readily available, that would be ideal. Because like I was saying, the iPad interpreter doesn’t necessarily help with the cultural context of things”. (Nurse) 3.22. “For the ICU and end of life, I will never recommend use of the iPad for interpretation. That will be something—I will not say it’s bad, but it’s not very nice. We’re talking and interpreting about death and dying situations, and just having the machine here sounds to me not very personal, however, it has been done many times”. (Interpreter) 3.23. “I feel like a lot of our Spanish speaking patients aren’t quite prepared for the fact that their loved one could actually die there in the hospital. I think a lot of that is due to the fact that they don’t get an interpreter consistently or maybe they try to use the iPad”. (Interpreter) |

| Family members | 3.24. “Even when they [Patients with LEP] have a family member there who speaks fluent English, I still try to have an interpreter as much as possible to make sure that they’re not just covering up with their English”. (Physician) 3.25. “I don’t really feel like that's a great thing to use family as interpreters just in case, again, I don't know what they're saying, and if they're truly telling what I'm saying, and repeating what the patient's saying back. (Nurse) 3.26. “Sometimes staff doesn’t call the interpreters. They use a family member. They think that the family's speak and understand more English than they actually do. That could lead to many misunderstandings. Maybe even false information”. (Interpreter) |

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of Professional interpreter’s role effects on clinician, patients and families with LEP in the ICU

Interpreter Roles

Verbatim interpretation

Verbatim interpretation describes strict linguistic interpretation of the clinician’s words. Most of the interpreters described their role as verbatim interpreters. Interpreters were comfortable in this role and some rejected any modification or expansion of that role (quotes 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4). However, some interpreters expressed frustration about the limits of simple verbatim interpretation (quote 2.5, quote 2.6 and 2.7).

Our results indicate that among physicians, the concept of the professional interpreters’ role as verbatim translators remains strong. We observed that the majority of physicians gave a straightforward description of the interpreter’s role as verbatim translators; in contrast with one nurse who referenced this role description. Physicians expressed mixed views about the verbatim interpreter role; some preferred this approach and others were less comfortable with it. (quote 2.8). Physicians also mentioned experiencing situations when tangential conversations occurred between the interpreter and patient or family member from which they felt excluded and did not understand what was discussed. (quote 2.9). Other physicians had a sense that sometimes the information relayed to the patient or family member was inadequate or incomplete. (quote 2.10).

Health literacy guardian

Physicians and nurses described the health literacy guardian role as important to alert clinicians when communication and understanding might be threatened. Participants highlighted the importance of this role in making sure patients and the clinical team understood each other including intervening beyond normal interpreting during discussions (quote 2.11, 2.12, 2.13). Interpreters were also seen as information advocates, especially when they empowered patients and families to ask questions when information was needed (quote 2.14). Interpreters also underscored patients’ and families’ right to be able to use an interpreter when needed (quote 2.15 and 2.16). Finally, interpreters provided practical information to improve understanding and outcomes (quote 2.17).

Clinicians and interpreters supported the view that interpreters should intervene if they thought patients or families did not fully understand the situation, potentially secondary to health literacy issues or some cultural or communication barrier. (quote 2.18 and 2.19)

Cultural Broker

Participants unanimously described the interpreter as functioning as a cultural broker acting as a bridge between diverse cultures, with diverse beliefs, medical systems, preferences, and ideologies. Interpreters viewed their role as a way to “break through some of the cultural barriers” or facilitating communication that incorporated background and patient’s habits and preferences (quote 2.20). Interpreters also acknowledged the importance of their role to explain and clarify cultural differences between patient’s expectations of the ICU environment and the actual ICU professional and institutional culture (quote 2.21). Sometimes interpreters needed to intervene when they detected cultural misunderstandings (quote 2.22 and 2.23).

One nurse voiced an opinion about the value of the interpreter as a person who could connect with patients, building trust and advising the clinical team. (quote 2.24)

Interpretation Modality

During the interviews participants described different examples representing how the different interpretation modalities positively or negatively influenced the interpreter’s role during communication in the ICU with patients and families with LEP and the beneficial or harmful impact of these influences on the interactions with those patients and families. We found that participants referenced the effects of particular modalities on the three interpreter roles previously described.

Modalities advantages

Participants listed the advantages of having in-person professional interpreters during communication with patients and families with LEP in the ICU. Physicians and nurses equally discussed the positive effects of in-person professional interpretation for cultural brokerage to increase understanding of cultural norms (quote 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5 and 3.6). Finally, participants affirmed the positive influence of in-person interpreters to resolve doubts/uncertainty and foster understanding among patients and families with LEP, within the health literacy guardianship role (quote 3.7 and 3.8).

Participants also stated the advantages of using other interpretation modalities and remarked that the immediate round the clock availability and broad language accessibility of video chat verbatim interpretation was useful. (quote 3.9, 3.10 and 3.11). Finally, some clinicians mentioned the benefits of using family members for Interpretation. The descriptions included the timeliness, accessibility, understanding of culture and trustworthiness for the patient. (quote 3.12, 3.13 and 3.14)

Modalities disadvantages

Participants referred to the limitations and concerns about the use of in-person interpreters, such as their limited availability which affects their participation and contribution for communicating with patients and families with LEP (quote 3.15, 3.16 and 3.17). Physicians mentioned the risk of technological difficulties with video chat remote interpretation that might affect the interpretation process with patients and families with LEP (quote 3.18 and 3.19). Nurses described the negative effects of remote interpretation related to the lack of cultural contextualization and the difficulties for building rapport (quote 3.20 and 3.21). Interpreters also noted that building rapport was harder with videoconferencing interpretation, and therefore it was unlikely that an interpreter could function as a health literacy guardian using this modality. (quote 3.22 and 3.23).

When mentioning family members as interpreters, some participants, highlighted the inaccuracy and uncertainty of family member’s verbatim interpretation during the communication process (quote 3.24, 3.25 and 3.26)

4. Discussion:

4.1. Discussion

The purpose of this work was to describe the healthcare team perceptions of the role of in-person professional interpreters, and the influence of different interpretation modalities on the interpreter’s role when communicating with patients and families with LEP in the ICU.

Our results highlighted a range of outlooks about the in-person professional interpreter role. Despite professional interpreters’ role mediating provider-patient interactions, interpreters continue to be trained following the conduit model; which assumes that the ideal interpretation is the same for all interpreters, the interpreters’ understanding is irrelevant, emotions should not be expressed, the interpreter’s attitude must be neutral and interactions with other team members or family members must be avoided. We noted in our sample that this role generated contradictory feelings, some interpreters conveyed satisfaction and ease with their verbatim role whereas other interpreters found this role frustrating.[80-83] We found evidence from our sample that prioritizing patient understanding required interpreters to step outside of their usual role, showing an initiative to extend their role and this was often supported by physicians and nurses.

Hsieh who interviewed clinicians in general hospital settings, noted that clinicians and interpreters had conflicts when clinicians worry about interpreters controlling the narratives and disrespecting role boundaries.[84] Our study highlights the existence of these conflicts in the ICU setting as well. Furthermore as the ICU treats critically ill and dying patients, these concerns may be exacerbated compared to other settings due to the complexity of disease, need for timely communication and often difficult decision making.[67]

Our study underscored the role of interpreters as health literacy guardians, primed to avoid negative consequences from ill-informed decision making or misunderstandings. Within this role, there was also an opportunity to improve the quality of care delivered and to empower patients. Although advocacy has been cited as a potential function of interpreters it is possible that the prominence of this role theme in the ICU setting is due to the environmental and medical complexity where advocacy becomes even more important. [37, 49, 85]

Cultural brokering has been described in the literature previously, by clinicians referring to professional interpreters as helping clinicians to provide culturally sensitive care,[48, 86] and interpreters outlining their role as mediators between cultures.[41] Cultural brokerage empowered interpreter’s sense of their role and its fundamental value to the patients, families and clinical team. Although we traditionally conceive of this as assisting clinicians in understanding patient and family backgrounds, in fact this is bidirectional and interpreter cultural brokering can assist patients in familiarizing themselves with the ICU culture and practice, which can be complex, unpredictable and time pressured; making interpreters “ICU cultural ambassadors”.[87]

Among professional interpreters, conflict about what role they should adopt reflects training and professional codes of conduct. The International Medical Interpreter Association and the National Code of Ethics on Interpreting in Health Care guide interpreters to abide by the principles of beneficence, respect and fidelity for cultural relevance and patients’ dignity and well-being.[88] According to these guidelines interpreters’ need to intervene to protect patients from harm when necessary.[89, 90] However, there are situations in which ambiguity in their role arises. [84, 90, 91]

Participants in our study discussed the influence of different interpretation modalities on the interpreter’s role. Participants described the benefits of in-person professional interpreters for communication with patients and families with LEP. Other work by Hadziabdic supported in-person interpreters for elderly patients facing end of life communication challenges.[92] Others have described the importance of paralinguistic clues that an in-person interpreter can elicit as helpful for supporting strong patient-clinician relationships.[81]

Remote interpretation modalities were also mentioned by many participants in our study. The participants in our study acknowledged the benefits of using video chat interpretation, but concerns related to the negative impact on communication during end of life discussions in critically ill patients still exist. Another study that evaluated about the use of video conference for interpretation services demonstrated that having access to videoconference interpreters is acceptable to patients and physicians, however that study was in an outpatient setting.[93]

Family members as interpreters were considered less useful for improving the communication process. This is important to take into consideration because the English proficiency of family members is not formally evaluated and if lacking could potentially contribute to interpretation mistakes and misunderstanding.[81, 82].

Limitations:

This study has several limitations. First, we conducted the study in a tertiary care academic medical center in the Midwest. Furthermore, the languages spoken by the patients in our ICUs are primarily Arabic and Spanish and our findings may specifically reflect interpretation in the context of these languages and cultural backgrounds.[94] Therefore, the generalizability of the study findings may be limited and the reflections of the interpreter’s role may not apply in other settings where the interpreter’s role and function may be different. Second, we interviewed a relatively small number of bedside nurses, physicians, and interpreters. In addition, our study may have had a tendency to selection bias, due to the recruitment methods used (email distribution list), in which participants may have self-selected to participate in the study due to having an affinity with this topic. Although our sample size was small, we did reach thematic data saturation across all groups. In addition, measures were taken to ensure trustworthiness, including coding in duplicate and triangulation by interviewing diverse member groups from the healthcare team (physicians, interpreters, and nurses) and a study team that included health research and disparities experts and clinicians. These measures strengthened the relevance of the discoveries. Third, we could not develop a conceptual framework from our data because in order to develop a future conceptual framework for this study population, further data would need to be collected, such as patient and family perspectives as well as perhaps observations of interpreters working in clinical practice. Fourth, this study focuses on participants’ reflections about language and cultural differences within the ICU. Due to the nature of ICU care including endotracheal intubation and sedation, communication barriers can occur for all patients whether they are English proficient or have LEP, our work focused on patients with LEP, interpreter use and communication. Fifth, we did not gather perceptions of patients and families with LEP about their views of the interpreters’ role and this is an area that research efforts should address in order to broaden our understanding.

4.2. Conclusion:

Our findings provide relevant new insights about the role of professional interpreters and interpretation modalities in the ICU, an area not previously described. Professional interpreters are fundamental for improving bi-directional verbal and non-verbal communication by providing reliable, understandable, and culturally tailored interpretation between patients and families with LEP and clinicians in the ICU. Regardless of the role or modality, professional interpreters are essential during communication in the ICU. Finally this work highlights the need for future research to further identify ways to implement ideal interpretation strategies in the ICU to improve practice and quality of care.

4.3. Practice implications:

The interpreter’s’ role, verbatim interpretations, cultural brokerage and health literacy guardian, are influenced by the interpreter’s comfort with functioning beyond expected roles. Patients may get benefits from having an interpreter who can function as a cultural or literacy guardian in the ICU setting where care is especially complex, good communication is vital, and end of life decision making is challenging. For serious end of life discussion in-person professional interpreters may provide more advantages towards the relationship building and communication with patients and families with LEP. Currently due to the COVID-19 pandemic clinician, interpreter, and patient interactions have been directly affected causing communication dynamics to change in unprecedented ways. Due to concerns about transmission of infection and need to save PPE for clinicians, there has been a decrease in use of in-person interpretation. Video interpretation has increased. Although we have highlighted the role of in-person professional interpreters, this new “normal” in patient care should make us aware of the relevance of remote interpreter modalities. Public policies and advocates are needed to help develop remote interpretation systems that ensure the best quality interactions, respecting the values, cultures, and desires of LEP patients and families. Our findings about the importance of health literacy guardianship, cultural brokering and verbatim interpretation are especially relevant during COVID-19. Since family members may not be present during care in the ICU and able to advocate for their loved ones, the need for a cultural broker and health literacy guardian becomes paramount for patients with LEP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support and conflict of interest disclosure:

This study was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and Internal Mayo Clinic critical care research committee funds. Its contents do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

List of abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- LEP

limited English proficiency

References:

- [1].IOM., International organization for migration. , 2020. (Accessed 16 Jul 2020 2020).

- [2].Portal MD, Migration and health, Retrieved from Migration Data Portal: https://migrationdataportal.org …, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Indicators GM, Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, International Organization for Migration, Berlin (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Giustini D, “It’s not just words, it’s the feeling, the passion, the emotions”: an ethnography of affect in interpreters’ practices in contemporary Japan, Asian Anthropology 18(3) (2019) 186–202. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J, Talking about sexual and reproductive health through interpreters: The experiences of health care professionals consulting refugee and migrant women, Sexual & reproductive healthcare 16 (2018) 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jaeger FN, Pellaud N, Laville B, Klauser P, The migration-related language barrier and professional interpreter use in primary health care in Switzerland, BMC health services research 19(1) (2019) 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hadziabdic E, Hjelm K, Register-based study concerning the problematic situation of using interpreting service in a region in Sweden, BMC health services research 19(1) (2019) 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sugie Y, Kodama T, Immigrant health issue in Japan-The global contexts and a local response to the issue, JIU Bull 22(8) (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shakya P, Tanaka M, Shibanuma A, Jimba M, Nepalese migrants in Japan: What is holding them back in getting access to healthcare?, PloS one 13(9) (2018) e0203645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brisset C, Leanza Y, Laforest K, Working with interpreters in health care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies, Patient education and counseling 91(2) (2013) 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Henke A, Thuss-Patience P, Behzadi A, Henke O, End-of-life care for immigrants in Germany. An epidemiological appraisal of Berlin, PloS one 12(8) (2017) e0182033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kale E, Syed HR, Language barriers and the use of interpreters in the public health services. A questionnaire-based survey, Patient education and counseling 81(2) (2010) 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gulati S, Watt L, Shaw N, Sung L, Poureslami IM, Klaassen R, Dix D, Klassen AF, Communication and language challenges experienced by Chinese and South Asian immigrant parents of children with cancer in Canada: implications for health services delivery, Pediatric blood & cancer 58(4) (2012) 572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Albahri AH, Abushibs AS, Abushibs NS, Barriers to effective communication between family physicians and patients in walk-in centre setting in Dubai: a cross-sectional survey, BMC health services research 18(1) (2018) 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Giese A, Uyar M, Uslucan HH, Becker S, Henning BF, How do hospitalised patients with Turkish migration background estimate their language skills and their comprehension of medical information–a prospective cross-sectional study and comparison to native patients in Germany to assess the language barrier and the need for translation, BMC health services research 13(1) (2013) 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM, Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study, International journal for quality in health care 19(2) (2007) 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sarver J, Baker DW, Effect of language barriers on follow-up appointments after an emergency department visit, Journal of general internal medicine 15(4) (2000) 256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Nápoles A, Schillinger D, Nickleach D, Pérez-Stable EJ, Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions, Medical care 50(4) (2012) 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G, Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates, Journal of general internal medicine 27(10) (2012) 1294–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bowen S, The impact of language barriers on patient safety and quality of care, Société Santé en français (2015).

- [21].Yeheskel A, Rawal S, Exploring the ‘Patient Experience’of Individuals with Limited English Proficiency: A Scoping Review, Journal of immigrant and minority health (2019) 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].McGrath P, Vun M, McLeod L, Needs and experiences of non-English-speaking hospice patients and families in an English-speaking country, American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 18(5) (2001) 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rawal S, Srighanthan J, Vasantharoopan A, Hu H, Tomlinson G, Cheung AM, Association between limited english proficiency and revisits and readmissions after hospitalization for patients with acute and chronic conditions in toronto, ontario, canada, Jama 322(16) (2019) 1605–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harmsen JH, Bernsen RR, Bruijnzeels MM, Meeuwesen LL, Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers?, Patient education and counseling 72(1) (2008) 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Douglas J, Delpachitra P, Paul E, McGain F, Pilcher D, Non-English speaking is a predictor of survival after admission to intensive care, Journal of critical care 29(5) (2014) 769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Czapka EA, Gerwing J, Sagbakken M, Invisible rights: Barriers and facilitators to access and use of interpreter services in health care settings by Polish migrants in Norway, Scandinavian journal of public health 47(7) (2019) 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].American Community Survey, Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over. 2009-2013; . https://www.census.gov/data.html. (Accessed 5/1/2019.

- [28].Hsieh E, Provider–interpreter collaboration in bilingual health care: competitions of control over interpreter-mediated interactions, Patient Educ. Couns. 78(2) (2010) 154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cappell MS, Universal lessons learned by a gastroenterologist from a deaf and mute patient: The importance of nonverbal communication and establishing patient rapport and trust, American annals of the deaf 154(3) (2009) 274–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hsieh E, “I am not a robot!” Interpreters' views of their roles in health care settings, Qualitative Health Research 18(10) (2008) 1367–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Flores G, The Impact of Medical Interpreter Services on the Quality of Health Care: A Systematic Review, Medical Care Research and Review 62(3) (2005) 255–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Maltby HJ, Interpreters: A double-edged sword in nursing practice, J Transcult Nurs 10(3) (1999) 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brach C, Fraser I, Paez K, Crossing the language chasm, Health Affairs 24(2) (2005) 424–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Metzger M, Investigations in healthcare interpreting, Gallaudet University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wu MS, Rawal S, “It’s the difference between life and death”: The views of professional medical interpreters on their role in the delivery of safe care to patients with limited English proficiency, PloS one 12(10) (2017) e0185659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Parmar R, Improving Physician-Interpreter Communication Strategies Within Toronto Hospitals, Global Health: Annual Review 1(3) (2018) 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S, Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature, Health services research 42(2) (2007) 727–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lee JS, Nápoles A, Mutha S, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE, Livaudais-Toman J, Karliner LS, Hospital discharge preparedness for patients with limited English proficiency: a mixed methods study of bedside interpreter-phones, Patient Educ. Couns. 101(1) (2018) 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dysart-Gale D, Clinicians and medical interpreters: negotiating culturally appropriate care for patients with limited English ability, Family & community health 30(3) (2007) 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tribe R, Lane P, Working with interpreters across language and culture in mental health, Journal of mental health 18(3) (2009) 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rosenberg E, Seller R, Leanza Y, Through interpreters’ eyes: comparing roles of professional and family interpreters, Patient education and counseling 70(1) (2008) 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Meyer B, Interpreter-mediated doctor–patient communication: the performance of non-trained community interpreters, Seminar: second international conference on interpreting in legal, health, and social service settings, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Haralambous B, Tinney J, LoGiudice D, Lee SM, Lin X, Interpreter-mediated cognitive assessments: Who wins and who loses?, Clinical Gerontologist 41(3) (2018) 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kilian S, Swartz L, Hunt X, Benjamin E, Chiliza B, When roles within interpreter-mediated psychiatric consultations speak louder than words, Transcultural Psychiatry (2020) 1363461520933768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lor M, Bowers BJ, Jacobs EA, Navigating challenges of medical interpreting standards and expectations of patients and health care professionals: the interpreter perspective, Qualitative health research 29(6) (2019) 820–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Piacentini T, O’Donnell C, Phipps A, Jackson I, Stack N, Moving beyond the ‘language problem’: developing an understanding of the intersections of health, language and immigration status in interpreter-mediated health encounters, Language and Intercultural Communication 19(3) (2019) 256–271. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Angelelli CV, Medical interpreting and cross-cultural communication, Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hsieh E, Hong SJ, Not all are desired: Providers’ views on interpreters’ emotional support for patients, Patient Educ. Couns. 81(2) (2010) 192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Karliner LS, O’Brien H, Gregorich SE, Pérez-Stable EJ, Clinician ratings of interpreter mediated visits in underserved primary care settings with ad hoc, in-person professional, and video conferencing modes, Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 21(1) (2010) 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Moreno MR, Otero-Sabogal R, Newman J, Assessing dual-role staff-interpreter linguistic competency in an integrated healthcare system, Journal of general internal medicine 22(2) (2007) 331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Leanza Y, Boivin I, Rosenberg E, Interruptions and resistance: a comparison of medical consultations with family and trained interpreters, Social science & medicine 70(12) (2010) 1888–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Joseph C, Garruba M, Melder A, Patient satisfaction of telephone or video interpreter services compared with in-person services: a systematic review, Australian Health Review 42(2) (2018) 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hsieh E, Not just “getting by”: factors influencing providers’ choice of interpreters, Journal of general internal medicine 30(1) (2015) 75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lee KC, Winickoff JP, Kim MK, Campbell EG, Betancourt JR, Park ER, Maina AW, Weissman JS, Resident physicians' use of professional and nonprofessional interpreters: a national survey, Jama 296(9) (2006) 1049–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].López L, Rodriguez F, Huerta D, Soukup J, Hicks L, Use of interpreters by physicians for hospitalized limited English proficient patients and its impact on patient outcomes, Journal of general internal medicine 30(6) (2015) 783–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schenker Y, Pérez-Stable EJ, Nickleach D, Karliner LS, Patterns of interpreter use for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency, Journal of general internal medicine 26(7) (2011) 712–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].O’Leary SCB, Federico S, Hampers LC, The truth about language barriers: one residency program’s experience, Pediatrics 111(5) (2003) e569–e573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Coates WC, Pitkin K, Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department, Jama 275(10) (1996) 783–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Watts K, Meiser B, Zilliacus E, Kaur R, Taouk M, Girgis A, Butow P, Kissane D, Hale S, Perry A, Perspectives of oncology nurses and oncologists regarding barriers to working with patients from a minority background: systemic issues and working with interpreters, European Journal of Cancer Care 27(2) (2018) e12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Blay N, Ioannou S, Seremetkoska M, Morris J, Holters G, Thomas V, Bronwyn E, Healthcare interpreter utilisation: analysis of health administrative data, BMC health services research 18(1) (2018) 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Jansky M, Owusu-Boakye S, Nauck F, “An odyssey without receiving proper care”–experts’ views on palliative care provision for patients with migration background in Germany, BMC palliative care 18(1) (2019) 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dungu KHS, Kruse A, Svane SM, Dybdal DTH, Poulsen MW, Wollenberg A, Juul AP, Poulsen A, Language barriers and use of interpreters in two Danish paediatric emergency units, Danish medical journal 66(8) (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Granhagen Jungner J, Tiselius E, Blomgren K, Lützén K, Pergert P, Language barriers and the use of professional interpreters: a national multisite cross-sectional survey in pediatric oncology care, Acta Oncologica 58(7) (2019) 1015–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Brandl EJ, Schreiter S, Schouler-Ocak M, Are trained medical interpreters worth the cost? A review of the current literature on cost and cost-effectiveness, Journal of immigrant and minority health 22(1) (2020) 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ganz FD, Engelberg R, Torres N, Curtis JR, Development of a model of interprofessional shared clinical decision making in the ICU: a mixed-methods study, Critical care medicine 44(4) (2016) 680–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Weinberg DB, Cooney-Miner D, Perloff JN, Babington L, Avgar AC, Building collaborative capacity: promoting interdisciplinary teamwork in the absence of formal teams, Medical care (2011) 716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU, Chest 133(3) (2008) 704–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients, American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 171(9) (2005) 987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Manuel D, Tanuseputro P, Stukel T, Pinto R, Scales DC, Laupacis A, Fowler RA, Association Between Immigrant Status and End-of-Life Care in Ontario, Canada, JAMA 318(15) (2017) 1479–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Barwise A, Jaramillo C, Novotny P, Wieland ML, Thongprayoon C, Gajic O, Wilson ME, Differences in Code Status and End-of-Life Decision Making in Patients With Limited English Proficiency in the Intensive Care Unit, Mayo Clinic proceedings, Elsevier, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zurca AD, Fisher KR, Flor RJ, Gonzalez-Marques CD, Wang J, Cheng YI, October TW, Communication with limited English-proficient families in the PICU, Hospital pediatrics 7(1) (2017) 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR, Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication, Chest 134(1) (2008) 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR, Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted ICU family conferences, Critical care medicine 37(1) (2009) 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Barwise AK, Nyquist CA, Suarez NRE, Jaramillo C, Thorsteinsdottir B, Gajic O, Wilson ME, End-of-Life Decision-Making for ICU Patients With Limited English Proficiency: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Team Insights, Critical care medicine 47(10) (2019) 1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J, Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, International journal for quality in health care 19(6) (2007) 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L, How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability, Field methods 18(1) (2006) 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Saldaña J, The coding manual for qualitative researchers, Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Daley BJ, Using concept maps in qualitative research, (2004).

- [79].Korstjens I, Moser A, Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing, European Journal of General Practice 24(1) (2018) 120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Dysart-Gale D, Communication models, professionalization, and the work of medical interpreters, Health communication 17(1) (2005) 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Rosenberg E, Leanza Y, Seller R, Doctor–patient communication in primary care with an interpreter: physician perceptions of professional and family interpreters, Patient education and counseling 67(3) (2007) 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Hsieh E, Ju H, Kong H, Dimensions of trust: The tensions and challenges in provider—interpreter trust, Qual Health Res 20(2) (2010) 170–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Brämberg EB, Sandman L, Communication through in-person interpreters: a qualitative study of home care providers' and social workers' views, Journal of Clinical Nursing 22(1-2) (2013) 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hsieh E, Conflicts in how interpreters manage their roles in provider–patient interactions, Social Science & Medicine 62(3) (2006) 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, Tranmer JE, O'Callaghan CJ, Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker, Intensive care medicine 29(1) (2003) 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Singy P, Health and Migration: Ideal Translator the Ideal of Translation?, La linguistique 39(1) (2003) 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- [87].Donchin Y, Seagull FJ, The hostile environment of the intensive care unit, Current opinion in critical care 8(4) (2002) 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Hernandez-Iverson E, IMIA guide on medical interpreter ethical conduct, International Medical Interpreters Association. Online (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [89].N.C.o.I.i.H. Care., National Code of Ethics for Interpreters in Health Care, (2004).

- [90].Barwise A, Sharp R, Hirsch J, Ethical tensions resulting from interpreter involvement in the consent process, Ethics & human research 41(4) (2019) 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Barwise AK, Nyquist CA, Espinoza Suarez NR, Jaramillo C, Thorsteinsdottir B, Gajic O, Wilson ME, End-of-Life Decision-Making for ICU Patients With Limited English Proficiency: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Team Insights, Critical care medicine 47(10) (2019) 1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Hadziabdic E, Lundin C, Hjelm K, Boundaries and conditions of interpretation in multilingual and multicultural elderly healthcare, BMC health services research 15(1) (2015) 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Schulz TR, Leder K, Akinci I, Biggs B-A, Improvements in patient care: videoconferencing to improve access to interpreters during clinical consultations for refugee and immigrant patients, Australian Health Review 39(4) (2015) 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Barwise AK, Nyquist CA, Espinoza Suarez NR, Jaramillo C, Thorsteinsdottir B, Gajic O, Wilson ME, End-of-Life Decision-Making for ICU Patients With Limited English Proficiency: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Team Insights, Crit Care Med (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.