Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species with a zoonotic origin and responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19). This novel virus has an extremely high infectious rate, which occurs through the contact of contaminated surfaces and also by cough, sneeze, hand-to-mouth-to-eye contact with an affected person. The progression of infection, which goes beyond complications of pneumonia to affecting other physiological functions which cause gastrointestinal, Renal, and neurological complication makes this a life threatening condition. Intense efforts are going across the scientific community in elucidating various aspects of this virus, such as understanding the pathophysiology of the disease, molecular biology, and cellular pathways of viral replication. We hope that nanotechnology and material science can provide a significant contribution to tackle this problem through both diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. But the area is still in the budding phase, which needs urgent and significant attention. This review provides a brief idea regarding the various nanotechnological approaches reported for managing COVID-19 infection. The nanomaterials recently said to have good antiviral activities like Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and quantum dots (QDs) were also discussed since they are also in the emerging stage of attaining research interest regarding antiviral applications.

Keywords: Antiviral applications, Carbon nanotubes, COVID-19, Pathophysiology, Quantum dots, SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

Global health scenario rarely faced a severe viral infection like COVID-19, which adversely affected almost all the aspects of human life. SARS-CoV-2 became a global pandemic in a very fast mode after its outbreak in December 2019 at Wuhan of China [1]. The disease stands first in the list of the most rapidly growing pandemic disease of recent world history. The genome size of SARS-CoV-2 consists of around 30,000 bases, and they are primarily classified by phylogenetic clustering into alpha, beta, gamma, and delta coronaviruses [2]. Alpha and beta coronaviruses are of significant concern to us because they primarily infect humans and other mammals. The fatality of these viruses arises due to severe respiratory tract infections, which can seriously become life-threatening to patients with other diseases and those with compromised immune system. People who have undergone medical procedures like surgery, lifestyle diseases like hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular problems also fall in the high-risk category of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Five days is the mean incubation period of SARS-CoV-2 with a basic reproduction number range from 1.5 to 4.92 [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 owing to the effects of the disease it had created across the global health scenario. Regarding vaccine development, intense clinical trials are ongoing in which most of them depends on nucleic acids due to their simpler production when compared to protein-based vaccines. The most advanced candidates are RNA vaccines targeting the spike (S) protein, which is considered an attractive target to lead to virus neutralization by antibodies induced by vaccination [4]. Nonetheless, more sophisticated vaccines targeting specific epitopes are desirable given the possibility of inducing undesired immune responses when full-length viral antigens are used [5]. Therefore, several emerging vaccinology approaches are emerging to the platform to produce novel therapeutic approaches which are both safe and easily accessible with feasible mode of administration (see Table 1, Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 virus [6].

| Protein name | Features |

|---|---|

| Spike (S) protein |

|

| Nucleocapsid (N) protein |

|

| Membrane matrix (M) protein |

|

| Envelope (E) proteins |

|

Table 2.

Various health implications of COVID-19 infections [3].

| Sl No | Organ system involved | Severe Disease | Diagnostic Signs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blood vessels/Vascular |

|

|

| 2 | Lung/Respiratory- Pulmonary |

|

|

| 3 | Gastrointestinal |

|

|

| 4 | Brain/Neurological |

|

|

| 5 | Kidney/Renal |

|

|

| 6 | Heart/Cardiac |

|

|

| 7 | Mental/Psychiatric |

|

|

1.1. A brief outlook of SARS-CoV-2: molecular structure and pathophysiology

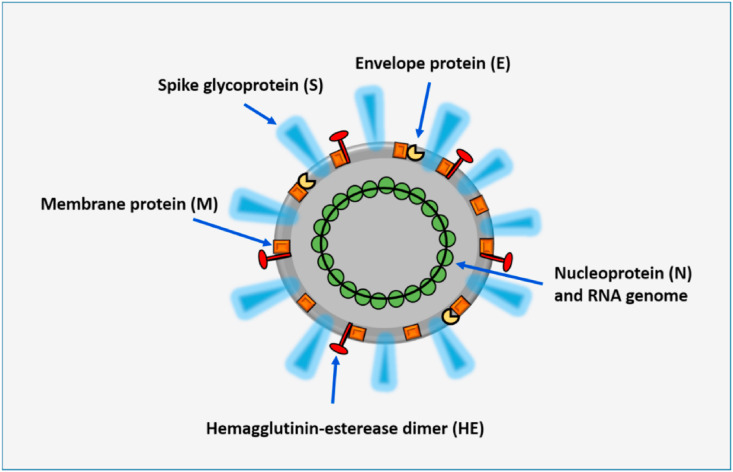

SARS-CoV-2 can be considered an enveloped virus that employs lipids from the host cell to form a new virion. The virus consists of a well-defined transmembrane protein with an outer phospholipid bilayer membrane. The unique toxicity and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 arise from the assembly of four proteins given below [6]:

The S protein of SARS-CoV-2 is having significant research attention since it contains the ACE-2- binding receptor in the upper lobular domain and acts as the vital factor for the entry of virus to the host cell. The lower realm of the S protein consists of the features required for the fusion of the virus to the host cell membrane. The structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 are schematically represented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 [7].

The process of replication (SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle) of SARS-CoV-2 virus can be illustrated by dividing into four key steps as described below [8]:

1.1.1. Attachment entry to the host cell

This step is determined by the spike protein (S) of SARSCoV-2, which has a strong binding affinity for the ACE-2 receptor. The binding of the S protein to ACE-2 leads to a proteolytic cleavage with a cellular protein called transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS-2). The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the classic class-I fusion protein, and it is the focus of interest in research for developing methods to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Class-I fusion proteins are also found in similar viruses like influenza and Ebola, and it acts as a protective agent for the fusion domain by keeping it well intact and inactive until the virus finds a suitable host cell where it can form a hairpin structure through the proteolytical activation process. This hairpin structure usually consists of a stretch of hydrophobic amino acids embedded into the target cell membrane, which completes the virus's entry to the host cell. Recent biochemical and crystallographic studies demonstrate the critical role of ACE-2 receptors in binding and internalization of the viral S protein, which enhances the importance of developing novel ACE-2 inhibitors which can act as potential therapeutic agents to fight SARS-CoV-2 infection.

1.1.2. Viral replicase transcription

This step initiates after the successful entry of virus followed by uncoating the envelope. This involves autoproteolytic cleavage of polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab which generates 15–16 nonstructural proteins (nsps) possessing specific functions. Computational modeling of drug molecules is focusing on developing molecules that can bind pockets in RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) and proteases.

1.1.3. Genomic transcription and replication

Studies indicate that the transcription process is complex involving numerous discontinuous transcription events. Kim et al. reported the presence of several RNAs which encode unknown ORFs, in addition to 10 known canonical RNAs. The authors were also able to identify 41 potential RNA modification sites with an AAGAA motif. Further investigations are essential to elucidate the different events associated with this process and the underlying molecular mechanism.

1.1.4. Translation of structural proteins

Fung et al. reported that structural proteins of coronavirus are subjected to post-translational modifications. Glycosylated S proteins were implicated in lectin-mediated virion anchoring and M proteins were also glycosylated.

1.1.5. Assembly and release of the virion

Literature reports the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) is the site of assembly of SARS-CoV-2 virion particles as evident from the studies of other family of coronaviruses. Various structural proteins play unique functions in this process. M proteins direct protein-protein interaction, with the scaffold leading to virion morphogenesis, M − S, and M − N interactions, and facilitating the recruitment of structural components to the assembly site. Coronavirus particles incorporated into the ERGIC are transported using smooth-wall vesicles, resulting in secretory pathway trafficking followed by the final release by exocytosis. These steps are also relevant from the drug design perspective to discover possible antiviral agents.

1.2. Health implications and therapeutic strategies of SARS-CoV-2

Literature reports the primary transmission route of SARS-CoV-2 is through the respiratory droplets from infected individuals. Li et al. list out the possible ways of viral infections to an individual as follows [9]:

-

1.

Through direct body contact with affected individuals

-

2.

Touching eyes, nose, and face with contaminated hands

-

3.

Transferring the virus by touching or smelling feces (very rare transmission)

-

4.

Contacting contaminated surface

Other forms of transmission are also reported by FDA in which the Fecal microbiota (FMT) isolated from SARS-CoV-2 positive people may also be a source for COVID-19 transmission according to recent FDA guidelines [10]. The stable survival of virus around 72 hours on plastic and stainless steel, more than 4 hours on copper, and up to 24 hours on cartons have been reported in the literature, but whether the virus has the potential to infect a healthy individual after this prolonged survival is still a matter of debate [11]. The most challenging task about COVID-19 management is diverse symptoms that vary from person to person. There can be mild symptoms that fail to recognize. In some cases, there may be severe symptoms that depend on the disease progression. The pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection is represented in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection [12].

Fever, loss of taste and smell, headache are some of the most common symptoms of COVID-19 infection which appear 2–14 days after exposure to SARS-CoV-2 viral particles [13]. Pneumonia-associated breathing problems will develop in case of severe infections, which progressed into the lungs and this can lead to hypoxemia which is a life-threatening condition [14]. Various physiological complications associated with COVID-19 disease is summarized in the following table [3]:

The underlying reason for this condition is due to the uncontrolled cytokine release, which is referred to as ‘Hypercytokinaemia’ (‘Cytokine storm’) characterized by an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the blood which ultimately leads to multiple organ failure (MOF) and death [15]. ‘Cytokine storm’ is a common feature of most of the viral infections and excessive cytokines lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome’ (ARDS) affecting lung cells [16]. The immune response pathway underlying COVID-19 infection can be schematically represented in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Immune response pathway of SARS-CoV-2 [1].

2. Role of nanotechnology in the management of viral diseases

Nanotechnology and material science have already proved their metal in assisting the conventional medicinal chemistry process through various aspects like targeted drug delivery [17], drug development perspectives etc [18]. Since the most effective strategy to manage viral diseases is to prevent contamination, appropriate use of nanomaterials can give potential benefits in this regard. Van Doremalen et al. reported that the minimum survival rate for SARS-CoV-2 has been found on copper surface compared to other surfaces like plastic and steel. Also later studies confirmed this result and observed that the viability of the virus will significantly decrease with an increase in the copper content in case of alloys [19]. This property was attributed to the release of Reactive oxygen species (ROS) by Copper nanoparticles and this feature is applicable to other corona viruses reported. Thus the antimicrobial and antiviral properties of nanoparticles which are widely reported in scientific literature become a matter of urgent attention in this regard. Many categories of nanomaterials including quantum dots [20], nanotubes [21], metal oxide nanoparticles [22], polymer nanocomposites [23], two dimensional nanomaterials [24], lipid nanoparticles [25] etc, reported for their good antimicrobial activities thus came into the platform of COVID-19 management.

The application and effect of nanomaterials against SARS-CoV-2 virus are still at the initial phase of exploration, but some studies are available which investigates the effects of these materials to similar other viruses like Ebola, SARS etc. Bhattacharjee et al. have initiated such work before the COVID-19 outbreak in which the metal-grafted graphene oxide (GO), for the modification of non-woven tissues showed to have very effective antimicrobial properties [26]. This can be correlated with the good antimicrobial action of Graphene composites with metals and other nanoparticles like TiO2. Chen et al. demonstrated that metal-loaded nanoparticles have good activity against both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses by using Silver-Graphene nanocomposites [27]. Krähling et al. showed the effectiveness of an antiviral air filtering system based on SiO2–Ag nanoparticles to protect from contamination of MS2 bacteriophage [28]. Silver (AgNPs) and Gold (AuNPs) nanoparticles are a few of the widely reported nanoparticles against viruses [29,30]The antimicrobial applications of Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles are widely explored and available in literature. In this review, we are focusing only on some Carbon based nanomaterials which are in the path of recent emerging research attention as represented in Fig. 4 . Exciting application was attained by carbon based nanomaterials due to their unique features like excellent biocompatibility [31] environmental friendly synthesis [32]and feasibility of tuning their properties for different applications [33]. We discuss details on two significant nanomaterials recently reported for their potent antiviral action and need significant and urgent attention regarding COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 4.

Recently reported carbon based nanomaterials against SARS-CoV-2.

2.1. Carbon nanotubes (CNT)

Cheng et al. reported an interesting simulation study to investigate the efficiency of CNT as inhibitors for HIV-1 protease [34]. Molecular docking and simulation results revealed that CNT could bind the protease in the active site, which depends on the size of CNT, which results in inhibiting the function of the protease. This process is strongly determined by the size of the CNT. A similar computational approach using CNT was reported by Krishnaraj et al. by selecting three geometrical variants of CNTs like Armchair, chiral and zigzag CNTs as the docking targets for HIV- Vpr, Nef, and Gag proteins which are the key proteins involved in HIV infection [35]. All the CNT models gave good results with promising binding affinity with the three key proteins, which suggests the application of CNTs as antagonistic agents in HIV research. Simulation studies that give good results with encapsulation of HIV inhibitors with CNT is also reported in the literature [36].

CNT is also reported as a successful nanocarrier for antiviral drugs. One such study reported the drug carrier property of Single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) using the antiviral drug Ribavirin against grass carp reovirus, which is a challenge for aquaculture [37]. The survival rate and infection rates were 29.7% and 50.4% respectively for the pristine ribavirin treatment group exposed to the highest concentration (20 mg/L) while the survival rate of 96.6% and infection rate of 9.4% were observed in the group treated with 5 mg/L ribavirin-SWCNTs complex after 12 days along with good retention rate of the drug in organs. Lannazzo et al. have studied antiviral potentiality of highly hydrophilic and dispersible carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) using two antiretroviral drugs CHI360 and CHI415, belonging to a series of active non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTI), and lamivudine (3 TC), used as anti-HIV agents [38]. It was observed that the more hydrophilic and dispersible oxidized samples, showed promising results with IC50 values of 11.43 μg/mL and 4.56 μg/mL respectively. Zhang et al. give the possibility of CNT to be used as carrier for DNA vaccine since 23.8% increase in the immune protective effect by SWCNTs for unmodified DNA vaccine [39] Al Garalleh et al. reported that the antiviral drug Ravastigmine could be encapsulated by SWCNT having a radius greater than 3.39 Å. SWCNT was also reported to have direct effect of reducing the defense mechanism of influenza A virus H1N1 [40].

Banerjee et al. reported that MWCNT conjugated with Protoporphyrin IX could reduce the infection rate of Influenza virus on mammalian cells in the presence of visible light [41]. This work suggests using MWCNT as ex-vivo antiviral agents due to the feasibility of recovering them from the solution phase. Bhattacharya successfully revealed the possibility of fabricating a sensor for viruses based on CNT and able to detect viral antigen with a titer of 10 TCID/mL [42]. It is important to monitor the bioavailability of drug molecule to elucidate the data regarding the drug's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics and thereby analyze its efficacy against the target. Atta et al. used Nano-magnetite/ionic liquid crystal modified carbon nanotubes composite electrode (CNTs/ILC/CNTs/FeNPs) for the determination of anti-hepatitis drug Daclatasvir (DAC) in human serum [43]. The sensor gives good detection for DAC in a wide concentration range of 0.003 μmol L to 15 μmol L-1. Further, the authors reported the excellent selectivity and stability of the sensor to detect DAC with other common antiviral drugs such as Acyclovir and also in the presence of other interfering species. Similar work was also reported by Azab and coworkers where they estimated DAC concentration using nanosensor based on MWCNT, Chitosan and Cobalt nanoparticles [44] Atta et al. reported MnO/graphene/ionic liquid crystal/carbon nanotube composite sensor for the determination of antiviral drugs Sofosbuvir (SOF), ledipasvir (LED) and acyclovir (ACY) [45] Zhu et al. reported that SWCNTs can significantly enhance the antiviral action of Isoprinosine against betanodavirus causing the disease viral nervous necrosis, which seriously affects central nervous system [46]. A recent and very interesting study was reported by Chen and coworkers, which reported that MWCNTs could modify cytokine and chemokine responses in mouse model with pandemic influenza a/H1N1 virus [47].

2.2. Quantum dots

Quantum dots are nanocandidates that have been reported widely for their biomedical applications due to unique optical and electronic features making them ideal theranostic agents [48]. Recent literature suggests the extension of their application to respiratory viruses including human corona virus (HCoV) [49]. Loczechin et al. reports such a study in which application of seven different carbonquantum dots (CQDs) for the treatment of the human corona virus HCoV-229E has been investigated [50]. The CQDs prepared through hydrothermal carbonization from ethylenediamine/citric acid as precursors and chemically functionalized with boronic acid ligands showed promising antiviral activity which is concentration dependent and EC50 value of 52 ±8μg mL-1. TheEC50 value lowered to 5.2 ± 0.7 μg mL-1with unmodified CQDs prepared from 4-aminophenylboronic acid as the precursor. Lannazo et al. investigated the HIV-inhibitory action of water soluble Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) prepared from MWCNTs [51]. This study observed that the conjugate of GQDs with non-nucleotide reverse transciptase inhibitor CHI499 is having good activity with an IC50 and EC50 value of 0.09 μg/mL and 0.066 μg/mL respectively. Curcumin is one of the most explored and classic bioactive compound for its wide range of bioactivity including anticancer [52], antimicrobial [53], anti-Alzheimers [54] and also as for boosting the immune system [55]. Lin et al. showed an exciting and very significant observation where the antiviral activity of Curcumin against Enterovirus 71 was significantly enhanced when it chemically transformed into CQDs [56]. This result was supported by the protection against hind-limb paralysis in new-born mice induced by Enterovirus 71. Artesunate and its derivatives are another categories of compounds that are reported to have inhibitory action against parasitic organisms through the formation of dihydroart emisinine via metabolic pathways. Pooventhiran et al. conducted a computational investigation and observed that the compound forms stable self-assemblies with surface-functionalized graphene quantum dots [57]. This complex can be used to detect the presence of the molecule using analytical methods.

2.3. Nanomaterials against SARS-CoV-2: current status and advancements

To the best of our knowledge, the actions of nanoparticles against respiratory viruses are not significantly explored. But we actively encourage readers to employ the already reported wide range of nanoparticles that are having good antiviral action to investigate against SARS-CoV-2. Significant studies in this perspective can solve the challenges associated with conventional treatment strategies which arise due to the resistance of the virus through mutation [58].

The protection from the transmission of viruses through the air is an effective method used to decrease the infection rate. The virus can transmit from an infected person through secretions like nasal/saliva droplets which makes the transmission difficult to manage. It can also be merged with aerosols present in high amount in the atmosphere. Thus employing successful preventive methods which prevent the passage of SARS-CoV-19 into the respiratory tract is equally important, like searching for therapeutic strategies. Leung et al. developed a good method which can filter out the aerosol-virus system from the atmosphere [59]. The authors successfully developed an efficient technology-based on charged Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofiber which can capture the target aerosol size set at 100 nm and reduce the COVID-19 transmission rate. Uniform sized fibers with excellent morphology and different diameters were fabricated in the work and later optimized to give good performance by successfully decreasing pressure drop across the fiber. The authors successfully fabricated one filter with 90% efficiency and ultralow pressure drop of only 18 Pa (1.9 mm water) while another filter meeting the 30 Pa limit has high efficiency reaching 94%. This method can be efficiently developed to make novel filter systems which can protect from not only COVID-19 but also other chronic airborne viruses and pollutants which can adversely affect human health. In a subsequent work the authors were able to reach promising quality factor (efficiency-to-pressure-drop ratio) of about 0.1–0.13 Pa-1. This 6-layer charged PVDF nanofiber filter is more user-friendly features like breathability than conventional respirators like N95 [60].

Somvanshi et al. reported detection systems for COVID-19 based on multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles [61]. The authors developed Zinc ferrite nanoparticles through combustion method and surface functionalized with silica and carboxyl-modified polyvinyl alcohol. This system is successful in automated detection of COVID-19 virus through RNA-extraction protocol and gives possibilities to develop efficient and rapid detection systems for molecular level diagnostics of COVID-19. Hassaniazad et al. reported an interesting work which elucidates the therapeutic effect of nano micelles containing curcumin and related immune responses during clinical trials [62]. Another work indicates the efficiency of curcumin to assist improvement in clinical manifestation and overall recovery of COVID-19 patients through the increased rate of inflammatory cytokines especially IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expression and cytokine secretion in COVID-19 patients [63]. In this work nano-curcumin is observed to cause significant decrease in IL-6 and IL-1β gene expression and secretion in serum without any effect on IL-18 mRNA expression and TNF- α concentration.

TiO2 nanoparticles are one of the well explored metal oxide nanomaterials due to their fascinating potential of applications in various fields like electronics [64] sensors [65] biomedical sectors [66]. Vadlamani et al. made an attempt to make the COVID-19 detection feasible using Cobalt functionalized TiO2 NPs as electrochemical sensoring probes [67]. The work involves one pot synthesis of TiO2 NPs through anodization method and detection of SARS-CoV-2 through sensing the spike protein present on the surface of the virus. This sensor possesses good potential for developing into highly sensitive sensing platform with linear detection range of 14–1400 nM concentration. Possibility of a similar biosensor was reported using graphene for both bacterial and viral pathogens which needs significant attention to develop into point-of-care diagnostics [68]. Wang et al. reports an interesting work which employs membrane nanoparticles prepared from ACE2-rich cells to block SARS-CoV-2 infection [69]. The nanomaterial used in the study is HEK-293T-hACE2 which contains 265.1 ng mg-1 of ACE2 on the surface, which is the main receptor of SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein and mediates viral entry into host cells. This material is biocompatible and acts as a nano-antagonist for blocking the entry of virus to the cytoplasm. Many other nanomaterials are at emerging stage of research which might possess promising features regarding viral detection ability and inhibitory action on COVID-19 [70]. This include nano-biosensors for the rapid detection of COVID-19 [71], nanomaterials which can assist the development of novel immunization approaches [72] etc. Literature also suggests the importance of rectifying the poor infrastructural conditions and limitations of health sector existing in different countries which can improve the fight against the virus [73,74].

3. Scope and future perspectives

World history rarely witnessed a severe viral pandemic like SARS-CoV-2 with extremely high infectious rate affecting the global health sector over the last decades. The virus spread around all over the world through extremely rapid pace after its outbreak and caused alarming death rate across the globe. COVID-19 thus became the point of focus of global scientific community and created very high impact in developing both the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to tackle the challenges associated with this infection. Nanomaterials became the first choice of research interest to solve the novel problems arise in scientific community due to their amazing features which we can't attain with bulk materials. Considering the perspective of COVID-19 pandemic, we feel material science should be the first choice of preference with special focus on nanostructured materials. Besides the novel approaches to solve the challenges of COVID-19 pandemic using various categories of nanomaterials are emerging in scientific literature, the area is still at infant stage.

We actively encourage researchers to come up with new solutions with a focus on both diagnosis of the virus like molecular sensors and also regarding the therapeutic aspects like increasing the bioavailability of antivirals already proven to have good activity against respiratory viruses. Genetic mutations of the virus are the most challenging problems faced by the conventional therapies since the virus cannot be destroyed using available drug molecules. Drug repurposing thus became an area which require urgent attention since the already reported drug molecules can be the potential drug molecules against SARS-CoV-2 with significant inhibitory action. Automated methods like high throughput screening (HTS) and computational chemistry approaches can significantly accelerate to develop efficient solutions to tackle this challenge. Toxicity of the nanomaterials is also a benchmark regarding fabricating nanomaterials for in vivo applications which should be given thorough importance. Biocompatibility and nanotoxicity aspects should be the screening criteria which should be given to each of the emerging nanomaterials for antiviral applications.

4. Conclusion

Scientific community is actively searching for a solution which can solve the problems associated with COVID-19 pandemic. New studies are emerging in which the nanomaterials observed to have promising features in fighting SARS-CoV-2 virus but the area is still in beginning phase. There are significant studies reported with other viruses like HIV, influenza, Ebola etc in which the nanotechnology and nanomaterials played a critical role. This is attributed to both the diagnostic aspects like fabrication of sensors, developing analytical tools to monitor the drug content etc and the therapeutic aspects like developing drug carrier vehicles, enhancing the bioactivity of antivirals and even the direct inhibitory action on viruses. The path for developing good solutions against COVID-19 pandemic will be easier through making clear understanding on the biomolecular pathways of viral replication.

Based on the findings that we reported in this review, we would like to highlight the following points to the readers:

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 is a class of respiratory virus having drastic infection rate and unclear pathophysiological implications which makes the COVID-19 pandemic difficult to manage.

-

•

Scientific research regarding material science platforms have been on the way to develop effective ways to solve the issues regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection. But the bridge between ‘lab to reality’ is very much narrow and needs to be modified by inventing novel nanomaterials which are easy to fabricate and create least adverse effects in environment.

-

•

Mutations of the virus are making the infection more complex which limits the application of available drugs not effective. the action of nanomaterials should be carefully investigated in different mutated viruses to get a clear scenario of the effectiveness of nanomaterials to combat COVID-19.

-

•

Eventhough there are materials like CNTs are reported for their good activity, the toxicity effects of these materials and associated adverse health effects which are already evident limits their applications in reality.

-

•

New materials or combination of materials with least or no toxicity should be fabricated with urgent attention to solve the issues regarding prevention and therapeutics of SARS-CoV-2 virus.

We hope this review will help the researchers to get an idea about the nanomaterials which have proven good antiviral action but not much explored. Nanomaterials reported against SARS-CoV-2 in the recent scenario have also discussed to get the updated status about the research.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank for the basic research support from National Institute of Technology Puducherry, Karaikal, India.

References

- 1.Sivasankarapillai V.S., Pillai A.M., Rahdar A., Sobha A.P. On facing the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) with combination of nanomaterials and medicine: possible strategies and first challenges. 2020. 2, 1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Woo P.C.Y. Coronavirus Genomics and Bioinformatics Analysis. Viruses. 2010;2:1804–1820. doi: 10.3390/v2081803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machhi J., Herskovitz J., Senan A.M., Dutta D., Nath B., Oleynikov M.D., Blomberg W.R., Meigs D.D., Hasan M., Patel M., Kline P., Chang R.C.C., Chang L., Gendelman H.E., Kevadiya B.D. The natural history, pathobiology, and clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infections. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;15:359–386. doi: 10.1007/s11481-020-09944-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belouzard S., Millet J.K., Licitra B.N., Whittaker G.R. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses. 2012:61011–61033. doi: 10.3390/v4061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahapatra S.R., Sahoo S., Dehury B., Raina V., Patro S., Misra N., Suar M. Designing an efficient multi-epitope vaccine displaying interactions with diverse HLA molecules for an efficient humoral and cellular immune response to prevent COVID-19 infection. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2020;9:871–885. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1811091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rey F.A., Lok S. Review common features of enveloped viruses and implications for immunogen design for next-generation vaccines. Cell. 2018;172:1319–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosales-Mendoza S., Márquez-Escobar V.A., González-Ortega O., Nieto-Gómez R., Arévalo-Villalobos J.I. What does plant-based vaccine technology offer to the fight against COVID-19? Vaccines. 2020;2:183. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Coronaviruses. 2015:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, Qun, Xuhua Guan, Peng Wu, Xiaoye Wang, Lei Zhou, Yeqing Tong, Ruiqi Ren R., Leung K.S., Lau E.H., Wong J.Y., Xing X. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus Cinfected pneumonia. N.Eng.J.Med. 2020:.1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ransom E.M., Burnham C.A., Jones L., Kraft C.S., McDonald L.C., Reinink A.R., Young V.B. Fecal microbiota transplantations: where are we, where are we going, and what is the role of the clinical laboratory? Clin. Chem. 2020;4:512–517. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubens J.H., Karakousis P.C., Jain S.K. Correspondence stability and viability of SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Jiang M., Chen X., Montaner L.J. Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020:17–41. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Symptoms of Coronavirus. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J., Covassin N., Fan Z., Singh P., Gao W., Li G., Kara T., Somers V.K. Association between hypoxemia and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020;95:1138–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrey A.C., Campbell R.A., Middleton E.A., V Pinchuk I., Beswick E.J. Cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19 : innate immune , vascular , and platelet pathogenic factors differ in severity of disease and sex. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021;1:55–66. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVA0820-410RRR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronit A., Berg R.M.G., Bay J.T., Haugaard A.K., Burgdorf K.S., Ullum H., Rørvig S.B., Plovsing R.R. Compartmental immunophenotyping in COVID- 19 ARDS : a case series. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sankar V., Kumar A., Joseph J. Nano-structures & nano-objects cancer theranostic applications of MXenenanomaterials : recent updates. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects. 2020;22:100457. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoso.2020.100457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havel H.A. Where are the nanodrugs? An industry perspective on development of drug products containing nanomaterials. AAPS J. 2016;18:1351–1353. doi: 10.1208/s12248-016-9970-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanDoremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., I Gerber S., et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as comparedwith SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivasankarapillai V.S., Jose J., Shanavas M.S., Marathakam A., Uddin M., Mathew B. Silicon quantum dots: promising theranostic probes for the future. Curr. Drug Targets. 2019;19:1255–1263. doi: 10.2174/1389450120666190405152315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang S., Pinault M., Pfefferle L.D., Elimelech M., Engineering C., V Y.U., Box P.O. Single-walled carbon nanotubes exhibit strong antimicrobial activity. Langmuir. 2007:8670–8673. doi: 10.1021/la701067r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin S. Antimicrobial activity of Zinc oxide nano/microparticles and their combinations against pathogenic microorganisms for biomedical applications: from physicochemical characteristics to pharmacological aspects. Nanomaterials. 2021 doi: 10.3390/nano11020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes M.M., Martins P., Correia D.M., Carvalho E.O., Gama F.M., Vazquez M., Bran C., Lanceros-Mendez S. Magnetoelectric polymer-based nanocomposites with magnetically controlled antimicrobial activity. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;1:559–570. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c01125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozulumba T., Ingavle G., Gogotsi Y., Sandeman S. Biomaterials Science Moderating cellular in flammation using 2-dimensional titanium carbide MXene and graphene variants †. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sharma M., Gupta N., Gupta S. Implications of designing clarithromycin loaded solid lipid nanoparticles on their pharmacokinetics, antibacterial activity and safety. RSC Adv. 2016;80:76621–76631. doi: 10.1039/C6RA12841F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharjee S., Joshi R., Chughtai A.A., Macintyre C.R. Graphene modified multifunctional personal protective clothing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 2019:1–27. doi: 10.1002/admi.201900622. 1900622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y., Hsueh Y., Hsieh C., Tzou D., Chang P. Antiviral activity of graphene – silver nanocomposites against non-enveloped and enveloped viruses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2016;13:430. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13040430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ed J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus triggers apoptosis via protein kinase R but is resistant to its antiviral activity. Kra V., Stein D.A., Spiegel M., Weber F., Mu E., editors. J. Virol. 2009;83:2298–2309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01245-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Lin Z., Zhao M., Guo M., Xu T., Wang C., Xia H., Zhu B. Reversal of H1N1 influenza virus-induced apoptosis by silver nanoparticles functionalized with amantadine. RSC Adv. 2016;92:89679–89686. doi: 10.1039/C6RA18493F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nanobiotechnol J., Kim J., Yeom M., Lee T., Kim H.O., Na W., Kang A., Lim J.W., Park G., Park C., Song D., Haam S. Porous gold nanoparticles for attenuating infectivity of influenza A virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12951-020-00611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jyoti J., Kiran A., Sandhu M., Kumar A., Singh B., Kumar N. Improved nanomechanical and in-vitro biocompatibility of graphene oxide-carbon nanotube hydroxyapatite hybrid composites by synergistic effect. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2021:104376. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaib M., Akhtar, Maqsood F., Shahzadi T. Green synthesis of carbon dots and their application as photocatalyst in dye degradation studies. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2021;1:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s13369-020-04904-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coville N.J., Mhlanga S.D., Nxumalo E.N., Shaikjee A. A review of shaped carbon nanomaterials. South Afr. J. Sci. 2011;107:1–15. doi: 10.4102/sajs.v107i3/4.418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng Y., Li D., Ji B., Shi X., Gao H. Structure-based design of carbon nanotubes as HIV-1 protease inhibitors: atomistic and coarse-grained simulations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2010;2:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NavaniethaKrishnaraj R., Chandran S., Pal P., Berchmans S. Investigations on the antiretroviral activity of carbon nanotubes using computational molecular approach.omb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2014;6:531–535. doi: 10.2174/1386207317666140116110558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z., Wang B., Wan B., Yu L., Huang Q. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications Molecular dynamics study of carbon nanotube as a potential dual-functional inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;436:650–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L., Gong Y.X., Liu G.L., Zhu B., Wang G.X. Protective immunity of grass carp immunized with DNA vaccine against Aeromonas hydrophila by using carbon nanotubes as a carrier molecule. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;55:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iannazzo D., Pistone A., Galvagno S., Ferro S., De Luca L., Maria A., Da T., Hadad C., Prato M., Pannecouque C. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of carboxylated and drug-conjugated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon N. Y. 2014;3977464:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C., Zheng Y.Y., Gong Y.M., Zhao Z., Guo Z.R., Jia Y.J., Wang G.X., Zhu B. Evaluation of immune response and protection against spring viremia of carp virus induced by a single-walled carbon nanotubes-based immersion DNA vaccine. Virology. 2019;537:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al Garalleh H. Modelling of the usefulness of carbon nanotubes as antiviral compounds for treating Alzheimer disease. Adv. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018;3:79. doi: 10.4236/aad.2018.73006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banerjee I., Douaisi M.P., Mondal D., Kane R.S. Light-activated nanotube – porphyrin conjugates as effective antiviral agents. Nanotechnology. 2012 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/23/10/105101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atta N.F., Ahmed Y.M., Galal A. Nano-magnetite/ionic liquid crystal modi fi ers of carbon nanotubes composite electrode for ultrasensitive determination of a new anti-hepatitis C drug in human serum. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2018;823:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azab S.M., Fekry A.M. RSC Advances on cobalt nanoparticles, chitosan and MWCNT for the determination of daclatasvir: a hepatitis C. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017:1118–1126. doi: 10.1039/c6ra25826c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azab S.M., Fekry A.M. Electrochemical design of a new nanosensor based on cobalt nanoparticles, chitosan and MWCNT for the determination of daclatasvir: a hepatitis C antiviral drug. RSC Adv. 2017;2:1118–1126. doi: 10.1039/C6RA25826C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atta N.F., Galal A., Ahmed Y.M. New strategy for determination of anti-viral drugs based on highly conductive layered composite of MnO2/graphene/ionic liquid crystal/carbon nanotubes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019;838:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2019.02.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu S., Li J., Huang A., Huang J., Huang Y., Wang G. Anti-betanodavirus activity of isoprinosine and improved e fficacy using carbon nanotubes based drug delivery system. Aquaculture. 2019;512:734377. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen H., Humes S.T., Rose M., Robinson S.E., Loeb J.C., Sabaraya I.V., Smith L.C., Saleh N.B., Castleman W.L., Lednicky J.A., Sabo-Attwood T. Hydroxyl functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes modulate immune responses without increasing 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 virus titers in infected mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004;20:115167. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2020.115167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikazar S., Sivasankarapillai V.S., Rahdar A., Gasmi S., Anumol P.S., Shanavas M.S. Revisiting the cytotoxicity of quantum dots: an in-depth overview. Biophys. Rev. 2020;3:703–718. doi: 10.1007/s12551-020-00653-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spike Q.D.S., Gorshkov K., Susumu K., Chen J., Xu M., Pradhan M., Zhu W., Hu X. Quantum dot-conjugated SARS-CoV - 2 spike pseudo-virions enable tracking of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 binding and endocytosis. ACS Nano. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loczechin A., Séron k., Barras A., Giovanelli E., Belouzard S., Chen Y.T., Metzler-Nolte N., Boukherroub R., Dubuisson J., Szunerits S. Functional carbon quantum dots as medical countermeasures to human coronavirus (HCoV) ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:42964–42974. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b15032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iannazzo D., Pistone A., Ferro S., De Luca L., Romeo R., Buemi M.R., Pannecouque C. Graphene quantum dots based systems as HIV inhibitors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018;9:3084–3093. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salem M., Rohani S., Gillies E.R. Curcumin, a promising anti-cancer therapeutic: a review of its chemical properties, bioactivity and approaches to cancer cell delivery. RSC Adv. 2014;21:10815–10829. doi: 10.1039/C3RA46396F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Da Silva A.C., De Freitas Santos P.D., Do Prado Silva J.T., Leimann F.V., Bracht L., Gonçalves O.H. Impact of curcumin nanoformulation on its antimicrobial activity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018;72:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elmegeed G.A., Ahmed H.H., Hashash M.A., Abd-elhalim M.M., El-kady D.S. Synthesis of novel steroidal curcumin derivatives as anti-Alzheimer’s disease candidates : evidences-based on in vivo study Synthesis of novel steroidal curcumin derivatives as anti-Alzheimer’s disease candidates : evidences-based on in vivo study. Steroids. 2015;101:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukherjee S., Baidoo J.N., Fried A., Banerjee P. Using curcumin to turn the innate immune system against cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;176:113824. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin C.J., Chang L., Chu H.W., Lin H.J., Chang P.C., Wang R.Y., Unnikrishnan B., Mao J.Y., Chen S.Y., Huang C.C. High amplification of the antiviral activity of curcumin through transformation into carbon quantum dots. Small. 2019;41:190264. doi: 10.1002/smll.201902641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pooventhiran T., Al-zaqri N., Alsalme A., Bhattacharyya U., Thomas R. Structural aspects, conformational preference and other physico-chemical properties of Artesunate and the formation of self-assembly with graphene quantum dots: a first principle analysis and surface enhancement of Raman activity investigation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;325:114810. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palestino G., García-silva I., González-ortega O., Palestino G., García-silva I., González-ortega O., Rosales-mendoza S. Expert review of anti-infective therapy can nanotechnology help in the fight against. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020;18:849–864. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1776115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woon W., Leung F., Sun Q. Electrostatic charged nanofiber filter for filtering airborne novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and nano-aerosols. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2020:116886. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.116886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scd W.W.L., Sun Q. Separation and Puri fi cation Technology Charged PVDF multilayer nano fi ber fi lter in fi ltering simulated airborne novel coronavirus (COVID-19) using ambient nano-aerosols. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2020;245:116887. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.116887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Somvanshi S.B., Kharat P.B., Saraf T.S., Saurabh B., Shejul S.B., Jadhav K.M. Multifunctional nano-magnetic particles assisted viral RNA-extraction protocol for potential detection of COVID-19. Mater. Res. Innovat. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14328917.2020.1769350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassaniazad M., Inchehsablagh B.R., Kamali H., Tousi A., Eftekhar E. The clinical effect of Nano micelles containing curcumin as a therapeutic supplement in patients with COVID-19 and the immune responses balance changes following treatment: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020:20–22. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04824-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valizadeh H., Abdolmohammadi-vahid S., Danshina S., Esmaeilzadeh A., Ghaebi M., Valizadeh S., Ahmadi M. International Immunopharmacology Nano-curcumin therapy , a promising method in modulating inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 patients. Int. Immunopharm. 2020;89:107088. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khalid A., Ahmad P., Alharthi A.I., Muhammad S. Unmodified titanium dioxide nanoparticles as a potential contrast agent in photon emission computed tomography. Microchem. J. 2021;160:105656. doi: 10.3390/cryst11020171. 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ullas U., Reddy N., Chandrashekar K., Mohan C.B. Titanium dioxide based bioelectric sensor for the acquisition of electrocardiogram signals. Microchem. J. 2021;160:105656. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuvakkumar M.I.R., Kumar G.R.P., Dhayalan B.S. Biomedical application of single anatase phase TiO2 nanoparticles with addition of Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) fruit peel extract. Appl. Nanosci. 2021;11:699–708. doi: 10.1007/s13204-020-01599-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vadlamani B.S., Uppal T., Verma S.C. Functionalized TiO2 nanotube-based electrochemical biosensor for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Sensors. 2020;20:1–10. doi: 10.3390/s20205871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang Z., Feng B., Xu J., Qing T., Zhang P., Qing Z. Biosensors and Bioelectronics Graphene biosensors for bacterial and viral pathogens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;166:112471. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang C., Wang S., Chen Y., Zhao J., Han S., Zhao G., Kang J., Liu Y., Wang L., Wang X., Xu Y. 2020. Membrane Nanoparticles Derived from ACE2-rich Cells Block SARS-CoV-2 Infection. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elkodous M., El-Sayyad G.S., Abdel-Daim M.M. Engineered nanomaterials as fighters against SARS-CoV-2: the way to control and treat pandemics. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Behera Soumyashree, Rana Geetanjali, Satapathy Subhadarshini, Mohanty Meenakshee, Pradhan Srimay, Kumar Panda Manasa, Ningthoujam Rina, Nath Hazarika Budhindra, Disco Singh Yengkhom. Biosensors in diagnosing COVID-19 and recent development. Sensors Int. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rangayasami Aswini, Kannan Karthik, Murugesan S., Radhika Devi, Kumar Sadasivuni Kishor, Raghava Reddy Kakarla, Raghu Anjanapura V. Influence of nanotechnology to combat against COVID-19 for global health emergency: a review. Sensors Int. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mishra NT Pramathesh, Das Sabya Sachi, Yadav Shalini, Khan Wasim, Afzal Mohd, Abdullah Alarifi, Ansari Mohammed Tahir, Hasnain Md Saquib, Amit Kumar Nayak. Global impacts of pre-and post-COVID-19 pandemic: focus on socio-economic consequences. Sensors Int. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agrahari Rishabh, Mohanty Sonali, Vishwakarma Kanchan, Kumar Nayak Suraja, Samantaray Deviprasad, Mohapatra Swati. Update vision on COVID-19: structure, immune pathogenesis, treatment and safety assessment. Sensors Int. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]