Abstract

Oncolytic reovirus preferentially targets and kills cancer cells via the process of oncolysis, and additionally drives clinically favorable antitumor T cell responses that form protective immunological memory against cancer relapse. This two-prong attack by reovirus on cancers constitutes the foundation of its use as an anticancer oncolytic agent. Unfortunately, the efficacy of these reovirus-driven antitumor effects is influenced by the highly suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). In particular, the myeloid cell populations (e.g., myeloid-derived suppressive cells and tumor-associated macrophages) of highly immunosuppressive capacities within the TME not only affect oncolysis but also actively impair the functioning of reovirus-driven antitumor T cell immunity. Thus, myeloid cells within the TME play a critical role during the virotherapy, which, if properly understood, can identify novel therapeutic combination strategies potentiating the therapeutic efficacy of reovirus-based cancer therapy.

Keywords: reovirus, oncolytic virus, myeloid cell plasticity, tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, tumor microenvironment, immune checkpoint blockade, combination therapy

1. Introduction

Cancers arise from genetically mutated cells that proliferate uncontrollably to form tumor masses, can infiltrate surrounding tissues, and also colonize distant niches via metastatic processes [1]. These oncogenic processes often facilitate the development of a highly suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) that consists of resident and infiltrating cells, cytokines and chemokines, and an extracellular matrix (ECM) that surrounds the tumor [2]. The immune constituents of the TME contain a high degree of inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity and often support tumor growth, progression, and metastasis [2]. Indeed, a diverse array of immune evasion strategies aiding tumor survival are the hallmark of TME.

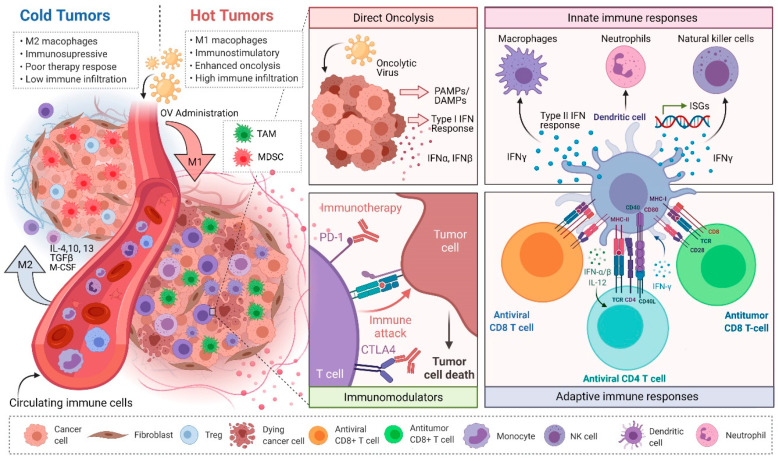

The extensive heterogeneity of the TME and the resultant immunosuppression has been a major hurdle to the development of effective cancer treatments. Immune cells within the TME belong to both innate (e.g., myeloid cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, NK cells) and adaptive (e.g., T cells, B cells) arms of the immune system, and their infiltration into the tumor is highly dependent on the soluble factors present in the TME [2]. Based on the presence of these immune cells within the TME, tumors with little to no presence of immune cells are referred to as “cold” tumors, whereas “hot” tumors have an active presence of immune cells and are more likely to respond to immunotherapeutic approaches including adjuvant therapies and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) [3] (Figure 1). Accordingly, therapeutic approaches that target both the cancer cells and the detrimental components of the TME have become expansive areas of research that have shown significant anticancer therapeutic potential. One such approach involves the use of oncolytic viruses (OVs) to simultaneously kill cancer cells and overturn tumor-associated immunosuppression [3,4,5].

Figure 1.

Overturning the tumor microenvironment (TME)-mediated immunosuppression using oncolytic virus (OV) immunotherapy. Administration of OVs can turn “cold” tumors “hot”, release otherwise inaccessible tumor antigens to be processed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) via oncolysis and also drive the activation of innate immune cells. Further, OVs alone or in combination with ICB therapy can repolarize immunosuppressive immune cells, such as TAMs and MDSCs, to antitumor phenotype and support the development of antitumor immunity. Abbreviations: OV: Oncolytic virus; PD-1: Programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; IFN: Interferon; ISG: Interferon stimulating genes; IL: Interleukin; PAMPs: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs: Damage-associated molecular patterns; TGFβ: Transforming growth factor beta; CSF: Colony-stimulating factor.

OVs are derived from naturally occurring or genetically modified viruses, and preferentially infect and lyse cancer cells through a process of oncolysis [6]. It is now clear that most cancers harbor one or more intrinsic mechanisms (e.g., defective antiviral interferon response) through which the immune evasion is facilitated [7]. Interestingly, such immune defects within cancer cells also make them preferentially susceptible to infection by OVs. Additionally, multiple immunosuppressive strategies within the TME provide additional support towards the replication of OVs. Thus, as compared to non-transformed or “normal” cells, cancer cells and the TME represent a preferential niche enabling OV oncolysis [8].

Currently, many viruses are being investigated as OVs in preclinical and clinical testing, including reovirus [9]. While mammalian orthoreovirus (herein reovirus) is the most prevalent strain used in OV research, the oncolytic capacity of other zoonotic strains, such as avian orthoreovirus, are actively being explored for their potential use in patients with pre-existing immunity to mammalian orthoreoviruses [10,11]. Reovirus preferentially replicates in cancer or transformed cells and kills them via direct oncolysis [12]. Additionally, reovirus also overturns numerous immune evasion mechanisms present within the TME and facilitates the activation of antitumor CD8+ T cell responses [13,14,15,16]. Similar to other OVs, oncolytic reovirus-driven CD8+ antitumor T cell responses can target cancer cells—both at local and metastatic sites. Most importantly, reovirus-driven antitumor T cell immune response can resist a tumor challenge, suggesting the ability to protect against possible cancer relapse, and is clinically desired [17]. Unfortunately, while these reovirus-induced antitumor T cell responses are very promising, their efficacy is stunted by the TME. More specifically, the TME orchestrates the recruitment and differentiation of suppressive immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) that actively inhibit antitumor immune activities and enable cancer cells to escape immune-mediated elimination. Considering this significant impact, here we discuss the role of MDSCs and TAMs in the context of oncolytic reovirus-induced antitumor immunity, the detailed understanding of which will aid the optimum harnessing of reovirus-based cancer therapies.

2. Myeloid Cell Plasticity and the TME

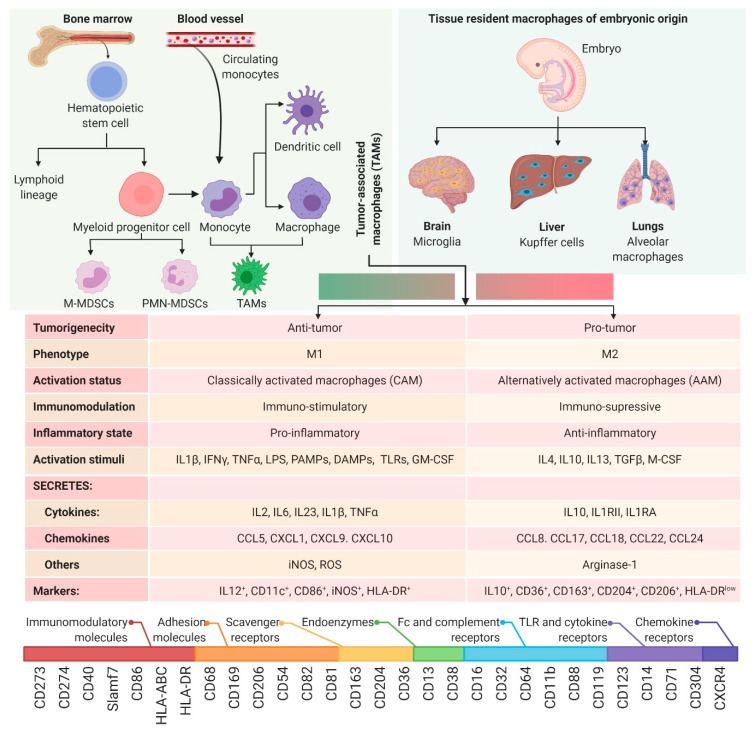

The innate immune system represents an intricate network of highly diverse cells that collectively function to identify and eliminate pathogens from the body. Amongst these cells are myeloid cells, from which monocytes and macrophages originate (Figure 2). Monocytes and macrophages are found in the peripheral blood and are recruited to various tissues where they differentiate into their effector phenotype depending on the stimuli encountered in their microenvironment [18]. In response to a pathogen, macrophages are the first line of defense and can drive the initiation of an adaptive immune response through phagocytosis and antigen presentation [19]. Additionally, macrophages play a significant role in dictating the immune response either by maintaining homeostasis or through the secretion of immunogenic molecules including cytokines, chemokines, and complement factors [19]. However, the differentiation and physiological function of myeloid cells is context dependent and adaptable based on the stimuli encountered in their microenvironment [20].

Figure 2.

Ontogeny of macrophages. Top panel (left): Sources of macrophage recruitment, namely bone marrow and circulating monocytes; top panel (right): Various types of tissue resident macrophages; middle table: Characteristics of macrophage dichotomy; bottom: The spectrum of surface markers used to phenotype macrophages. Abbreviations: CAM: Classically activated macrophages; AAM: Alternatively activated macrophages; M-MDSC: Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell; PMN-MDSC: Polymorphonuclear/granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell; IL: Interleukin; IFN: Interferon; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; PAMPs: Pathogen-activated molecular patterns; DAMPs: Damage-associated molecular patterns; TLR: Toll-like receptor; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; CSF: Colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; TGF: Transforming growth factor; iNOS: Nitric oxide synthase (inducible); ROS: Reactive oxygen species; CCL: Chemokine ligand; CXCL: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; CD: Cluster of differentiation; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen; Slamf7: Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule F7.

2.1. M1 vs. M2 Macrophage Paradigm

Macrophage diversity is so extensive that it has been a significant cause of controversy within the field in regard to how different populations of macrophages should be classified [21,22,23,24]. While this debate still rages within the field of macrophage biology, the majority of researchers have adopted a model where macrophages are broadly classified into two types that represent opposing ends of a polarization spectrum: Classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) (Figure 2). M1 macrophages are polarized in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli such as interferon-gamma (IFNγ), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation. These cells develop a phenotype with functions that include pro-inflammatory cytokine production, endothelial cell activation, antiviral defense, and immune cell recruitment. Conversely, alternatively activated (M2) macrophages differentiate in response to anti-inflammatory stimuli such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), generating a phenotype that specializes in tissue homeostasis, phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4, -10, -13) [22,25,26]. In the context of cancer, M1 macrophages have antitumor properties, whereas M2 macrophages are immunosuppressive and are tumor-promoting [27]. Unfortunately, the current suboptimal levels of therapy responses to advanced treatments such as immune checkpoint blockade can be attributed to the complex heterogeneity within in the TME [28]. This complexity further makes it challenging to identify patients who will respond better to these drugs. A recent quest carried out in 98 pan-cancer patient data in the spirit of identifying biomarkers of value reiterated the prognostic significance of M1/M2 macrophage ratio [29,30]. It is also worth mentioning that the stimuli of polarization is a net result of the dynamic spectrum of various spatiotemporal signals present at the local environment [31]. While this nomenclature reflects a highly simplified model of myeloid cell plasticity, a comprehensive review of monocyte/macrophage dichotomy lies outside of the scope of this review and has been described elsewhere [32,33]. However, an understanding of how myeloid cell polarization is regulated in the context of the TME is critical in addressing the shortcomings of OV therapies.

2.2. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs)

TME-associated growth factors, cytokines and chemokines mediate altered hematopoiesis that drives the generation of immunosuppressive MDSCs [34]. These chemotactic agents within TME also facilitate the migration of MDSCs. In animal models, the presence of C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2 or MCP-1), CCL3, CCL4, C-X-C ligand 12 (CXCL12), IL-6, IL-1β, M-CSF and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the TME promoted MDSC infiltration [35,36]. MDSCs can be of polymorphonuclear/granulocytic phenotype (PMN-MDSC) or the monocytic phenotype (M-MDSC) [37]. Monocytes differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells; whereas polymorphonuclear cells give rise to neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells [38]. The proliferation and differentiation of MDSCs are regulated by similar growth factors that regulate macrophage differentiation; namely M-CSF, G-CSF and GM-CSF [39]. Interestingly, however, MDSC recruitment and differentiation is believed to be much more complex than that of macrophages since signaling pathways are required to maintain their highly immature state [39]. Apart from the growth factors mentioned above, additional MDSC signaling pathways include a combination of TLR4 and IFNγ signaling, and the activation of the STAT3 pathway, amongst many more [40,41]. High frequencies of these cells clinically correlate with increased oncogenesis, metastasis and poor prognosis [37,42,43]. Moreover, the physical interaction between TAMs and MDSCs results in pro-tumorigenic Th2 immune response [44]. MDSCs also suppress antitumor T cell activities and promote angiogenesis [45]. Therefore, myeloid cell reprogramming strategies, alone or in combination with immunotherapies and anti-angiogenic strategies, will prove useful in combating these suppressive stimuli within the TME.

2.3. Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

While often considered synonymous with M2 macrophages, TAMs can have characteristics of both M1 and M2 phenotypes depending on the type of cancer, stage of the tumor, and the TME [46]. Therefore, TAMs have a distinct phenotype from conventional macrophages, exhibiting significantly more immunosuppressive capacities than traditional M2 macrophages [46]. TAMs can originate from tissue resident macrophages or can develop from monocyte precursors in the blood [47]. The functional fate of TAMs is decided upon their recruitment into the TME in response to growth factors, cytokines and chemokines [27,48]. Signaling pathways known to drive TAM differentiation include VEGF, M-CSF, IL-4, CCL-2, -9, and -18 [48]. TAMs have been shown to make up to 50% of a tumors mass [49,50] and are therefore critical regulators of how a patient will respond to therapy [49]. In fact, TAM abundance in the TME has been shown to negatively correlate with survival in numerous cancers including breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, head and neck cancer, lymphoma, and bladder cancer [22,31,32,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Moreover, TAMs have been shown to be instrumental for tumor relapse and metastasis in breast cancer [59,60,61]. Meta-analysis of clinical reports highlights that over 80% of the studies show a positive correlation between increased TAM density and poor patient prognosis [62]. CCL2 has also been reported to recruit TAMs which promotes metastasis in bone [63] and breast cancer [64] models. Interestingly, GM-CSF administration has been shown to counteract the immunosuppression and promote antitumor environment, likely by driving a more favorable pro-inflammatory TAM phenotype in addition to stimulating DC differentiation [65].

While TAMs and MDSCs are often similar in cellular functionality, they can be phenotypically distinguished from each other based on surface marker expression [48]. Additionally, while MDSCs are considered entirely tumor-promoting, TAMs have been shown to have both pro- and anti-tumor properties depending on the type of cancer, likely due to their previous roles as tissue resident macrophages prior to oncogenesis [48,66]. A better understanding of the intricacies involved in TME-TAM signaling will undoubtably provide more anticancer treatment options.

3. Reovirus-Based Dual-Prong Anticancer Actions and Myeloid Cells

Two main modes through which reovirus performs antitumor functions during virotherapy are: direct oncolysis and antitumor immunity. Following the therapeutic administration in cancer-bearing hosts, the efficacy of these reovirus-induced anticancer effects can be influenced by the myeloid cells within the TME.

3.1. Direct Oncolysis

While immunosuppression within the TME provides cancer cells with a competitive growth advantage, it also renders them conducive to reovirus infection and replication [67,68,69]. Here, the immunosuppressive components of the TME create an immune-privileged enclosure away from the reach of the properly functioning immune cells.

Like most viruses, productive reovirus infection is dependent on the host intracellular replication machinery [70]. The process of cellular transformation within cancer cells brings about dysregulation in metabolism and aberrant cell signaling pathways [1]. Reoviruses demonstrate an inherent propensity to infect transformed cells with such disrupted physiology [12]. The release of progeny viruses often leads to host cancer cell death, which makes it a lytic life cycle; the process is known as “oncolysis” [71]. Direct oncolysis by viral replication is facilitated using various signaling pathways involving TNFα, Fas ligand (FasL), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), ROS and others [72,73,74], and can lead to different types of cell death in different cancers [67,75]. Thus, reovirus-induced oncolysis of cancer cells involves multifaceted and complex interaction between cancer cells and surrounding tissues. In line with their immuno-modulatory effects, myeloid cells can influence reovirus-mediated oncolysis of cancer cells in a context-dependent manner. For example, M1 vs. M2 macrophages themselves bear different susceptibilities to virus infection and thus hold capacities to differentially regulate virus loads in the hosts [76]. Similarly, MDSCs themselves can carry replication-competent reovirus [77]. Nonetheless, the evidence on the role of myeloid cells on reovirus-mediated direct oncolysis, despite being important, is still in its infancy, and must be pursued further. These studies also should provide consideration for myeloid cell heterogeneity as the lack of information on the precise myeloid cell phenotypes has generated rather conflicting information for the OV field. For instance, while enhanced replication and oncolysis has been attributed to increased macrophage presence in oncolytic herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of glioma, the depletion of macrophages in HSV-treated glioma was shown to result in higher titers of OV [78]. Similarly, in mesothelioma models, the presence of MDSCs hindered the ability of oncolytic modified vaccinia Tiantan (MVTT) to perform oncolysis and ablation of MDSCs restored the oncolytic efficacy of MVTT [79]. These findings are indicative that myeloid cells are central in orchestrating the OV-mediated oncolysis, and validate the notion that targeted reprogramming of MDSCs and TAMs will serve as a viable strategy to improve OV efficacy.

3.2. Reovirus-Induced Antitumor Immunity

Unfortunately, while the suppressive nature of the TME is actively involved in facilitating a productive reovirus infection [80], it also represents a daunting hindrance towards the initial activation and subsequent actions of antitumor CD8+ T cells [81]. Interestingly, reovirus has been shown to overturn many different immune evasion strategies present within the TME; examples include the promotion of antigen presentation and co-stimulation by antigen-presenting cells (including macrophages), recruitment of APCs and T cells within TME, subsequent trafficking to the lymph nodes, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cumulatively, these reovirus-driven immunological events drive the successful activation of protective antitumor CD8+ T cell responses. Unfortunately, the therapeutic injection of reovirus also promotes the recruitment of suppressive MDSCs which dampen the functions of antitumor CD8+ T cells [82]. Indeed, the inhibition of MDSC recruitment via C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2)-dependent mechanism or gemcitabine potentiates reovirus-induced antitumor effects [15,83]. Further, reovirus successfully inhibits the immunosuppressive activity of MDCSs in a TLR3-dependent manner and promotes antitumor CD8+ T cell responses [84]. Thus, the TME hosts a dynamic environment which although immunosuppressive can be harnessed to drive reovirus-induced antitumor benefits [6]. It should be noted that, similar to reovirus, the therapeutic implications for myeloid cells apply to other OVs as well. For example, oncolytic adenovirus and HSV infection led to increased infiltration of immunostimulatory macrophages in glioma [85,86], and exposure to oncolytic paramyxovirus resulted in skewing of macrophage phenotype towards antitumor capacity [87]. Further, oncolytic HSV in combination with gemcitabine has shown to effectively suppress MDSCs and result in tumor regression and enhanced oncolysis accompanied by antitumor CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses [88]. Going forward, the context-dependent consideration for myeloid cell heterogeneity within OV-induced antitumor immune responses will be a key factor. Therefore, combination therapeutic strategies targeting the immunosuppressive aspects of the TME with specific regards to direct oncolysis and antitumor immunity will create optimal clinical outcomes from reovirus-based cancer therapy.

4. Targeting Myeloid Cells to Improve Reovirus Therapy

Considering the immunosuppressive effects of the MDSCs and TAMs on antitumor immunity, currently many therapeutic strategies are being developed or tested to target these immunosuppressive myeloid cells, and thus are discussed below. It is worth mentioning that myeloid cells are merely one of many immunosuppressive cell types in the TME. For example, CD4+FoxP3+regulatory T cells (Tregs) are highly immunosuppressive, and often play a central role in driving tumor immune evasion and suppression of antitumor immunity [89]. In fact, myeloid cells have been shown to drive the differentiation of Tregs in the TME through direct cell-cell interactions [90], further supporting the rational to therapeutically target MDSCs and TAMs during OV therapy. While a proper description of Treg biology and function lies outside the scope of this review, this has been discussed extensively elsewhere [89,91,92]. Here, we discuss different combination therapy strategies aimed at targeting suppressive myeloid cells. Of note, many of the strategies are not yet used in conjunction with OVs; however, they are still discussed in anticipation of their future use in the context of OV-based cancer therapies such as reovirus.

4.1. Blocking Recruitment

Blocking MDSCs and TAM recruitment can be an effective strategy to hinder tumorigenesis and alleviate immunosuppression. As CCL2 recruits TAMs and MDSCs that are positive for chemokine receptor CCR2 in TME [93,94], blockade of CCL2/CCR2 reverts the MDSC infiltration in in vivo models [95]. Accordingly, the ablation of CCR2 inhibition causes tumor relapse, favoring angiogenesis and metastasis in breast cancer models [96]. CCR2 inhibitors such as carlumab (CNTO 888), PF-04136309, MLN1202, BMS-813160, and CCX872-B are currently in clinical trials [97]. The CXCL-12-CXCR-4 axis also orchestrates the recruitment of TAMs via endothelial barrier into hypoxic tumor regions [98], and targeting CXCL-12-CXCR-4 axis alleviates tumor burden and metastatic susceptibility in breast, prostate, and ovarian cancer models by averting TAM infiltration [99,100]. Unfortunately, therapeutic administration of reovirus drives immediate recruitment of MDSCs in TME, which, if inhibited, potentiates antitumor CD8+ T cell responses [15].

4.2. Depleting Macrophage Populations in the TME

TAMs can be directly depleted by triggering apoptosis [101]. Bisphosphonates preferentially target phagocytic cells such as TAMs and elicit myeloid cell cytotoxicity [102]. Zoledronate, a third-generation bisphosphonate displays cytotoxicity towards matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9)-expressing TAMs and enhances antitumor activity of macrophages by reprogramming monocyte differentiation towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype [103]. Trabectedin, a chemotherapeutic agent, selectively elicits cell death in monocytes including TAMs through the activation of the caspase-8 cascade via TRAIL receptors [104]. Retrospective analysis of data from 34 patients who received trabectedin-based chemotherapy revealed that 56% of patients were found to have a reduction in monocytes in the tumor [104]. Trabectedin administration prior to oncolytic HSV injection has been shown to deplete intratumoral myeloid cells including macrophages [105]. Importantly, Trabectedin prevented the increase in intratumoral infiltration of these cells upon oncolytic HSV injection [105]. The depletion of TAMs also markedly increased the antitumor efficacy of oncolytic HSV by significantly altering the TME [105] in many models including Ewing Sarcoma and glioblastoma [106]. These and similar other myelolytic treatments are promising strategies to synergistically increase OV therapy efficacy.

4.3. Reprogramming Metabolism

In macrophages, growth-factor-driven metabolic rewiring results in phenotypic alterations that enable them to adapt to their environment and perform their immune effector functions. For example, in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, M1 macrophages disrupt the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle at two points—after citrate and after succinate—driving fatty acid synthesis (FAS) and IL-1β production which are central to their pro-inflammatory phenotype [107,108,109,110]. Conversely, in the context of anti-inflammatory stimuli, M2 macrophages have an intact TCA cycle that favors mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), resulting in a greater yield of ATP [107,108,109,110]. Accordingly, inhibition of ATP synthesis in these macrophages using ATP synthase inhibitor, oligomycin, or hexokinase inhibitor, 2-deoxyglucose suppresses anti-inflammatory gene and marker expression, and overall function [111,112]. Therefore, it is not surprising that TME-associated metabolic aberrations affect the functional attributes of TAMs. Thus, targeted metabolic reprogramming of macrophages in the context of metabolic perturbations within the TME represent next frontiers in harnessing OV cancer therapy efficacies.

4.4. Reprogramming Cellular Signaling

OVs in combination with strategies aimed to overturn the immunosuppressive cues in the TME are effective tools to reprogram myeloid cells towards an antitumor phenotype. TAMs and MDSCs can be re-educated to be tumoricidal using strategies such as, but not limited to CSF1/CSF1R blockades, TLR agonists, PI3Kγ inhibitors, CD40 agonists, and Class IIa histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors [113]. The surface receptors of macrophages that facilitate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity/phagocytosis (ADCC/ADCP) are attractive targets. Tumor cells express CD47 which recognize signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) receptor on macrophages to help them escape immune surveillance [114]. However, this can be overcome by employing anti-SIRPα antibody to elicit macrophage-dependent cellular phagocytosis [115]. TLRs are also capable of directing TAMs towards a pro-inflammatory antitumor phenotype, when subjected to TLR agonists. TLR7/TLR8 agonists have been shown to counteract subcutaneous melanoma in vivo, in concert with ICB therapy. CSF1R inhibition when combined with oncolytic adenovirus and anti-PD-1 antibody enhances tumor regression and confers survival advantage to mouse models of colon cancer [116]. An oncolytic adenovirus engineered with TLR agonistic immunostimulatory-islands can overcome myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression and elicit effective antitumor T cell responses [117]. Arming an oncolytic adenovirus with CD40L successfully repolarizes M2 macrophages, induces oncolysis and promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and expansion [118]. These arguments underline the potential of reprogramming TAMs and MDSCs for enhancing OV efficacy.

Considering the central role of GM-CSF in myeloid cell biology, OVs have been engineered to express this cytokine. Recently, Kemp et al., successfully generated reoviruses that express murine and human GM-CSF (rS1-mmGMCSF and rS1-hSGMCSF, respectively). In a murine model of pancreatic cancer, intratumoral treatment with rS1-mmGMCSF resulted in an increase in T cell activation at distant metastatic tumor sites [119]. This supports the notion that reprogramming the TME by targeting myeloid populations improves the ability of reovirus to drive an antitumor T cell response. With respect to other OVs, Pexa-Vec (also known as JX-594), a vaccinia virus, has been engineered to express GM-CSF in order to repolarize infiltrating MDSCs and TAMs [120]. Trials using Pexa-Vec have demonstrated safety and showed antitumor activities in colorectal, hepatocellular and pediatric cancer [121,122]. Similarly, RP1, an oncolytic herpes simplex virus (HSV) armed with GM-CSF encoding region [123], has reported increased immune infiltration and robust CD8+ T cell responses [124]. The first approved [125] OV for clinical use namely T-VEC (Talimogene laherparepvec) [126], is armed with one cassette encoding human GM-CSF [127]. A list of clinical trials which use OVs in combination with immunomodulating therapies aimed to reprogram MDSCs and TAMs in various cancers can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of clinical trials using OVs in combination with immunomodulatory strategies for various cancers.

| Trial | Virus Type | OV Agent | Immunomodulatory Therapy | Phase (s) | Cancer (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | Description | |||||

| NCT03747744 | HSV | T-Vec | CD1c (BDCA-1)+ myDC | CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells | I | Melanoma |

| NCT02197169 | Adenovirus | DNX-2401 | IFNγ | Pro-inflammatory | I | Glioblastoma or Gliosarcoma |

| NCT02143804 | Adenovirus | CG0070 | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | II | Bladder Cancer, High Grade, Non-Muscle Invasive |

| NCT00625456 | Vaccinia | RACVAC (JX-594) | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | I | Melanoma, Lung Cancer Renal Cell Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck, Neuroblastoma |

| NCT01169584 | Vaccinia | RACVAC (JX-594) | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | I | Rhabdomyosarcoma, Lymphoma Wilm’s Tumor, Ewing’s Sarcoma |

| NCT04725331 | Vaccinia | BT-001 | Anti CTLA-4 mAb (encoded) | ICB | I, II | Solid Tumor, Adult Metastatic Cancer Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Melanoma, Triple Negative Breast Cancer Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NCT04050436 | HSV | RP1 | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | II | Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| Cemiplimab (combination) | PD-1 | |||||

| NCT03767348 | HSV | RP1 | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | II | Melanoma, NSCLC |

| Nivolumab (combination) | PD-1 | II | ||||

| NCT00554372 | Vaccinia | JX-594 | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | II | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| NCT00629759 | Vaccinia | JX-594 | GM-CSF (encoded) | M1 polarizer | I | Liver neoplasms |

| NCT04521764 | Measles | MV | NAP (encoded) | Secretes neutrophil activating protein | I | Breast cancer |

4.5. Immune Checkpoint Blockade (ICB)

Blockade of immune checkpoint proteins namely, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), its ligand PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) in combination with reovirus have shown potential in improving efficacy of reovirus therapy (Table 2). This therapeutic approach is not restricted to reovirus, as other OVs are also increasingly explored to function in synergy with ICB therapies. Table 3 lists the clinical trials currently underway which employ OVs in combination with ICB therapies for various cancers. Within these mainstream immune checkpoints, PD-L1 is known to be expressed on MDSCs and TAMs, and thus ICB with anti-PD-L1 strategies can directly affect myeloid cell functions [128]. While PD-1 and CTLA-4 are known to be expressed mainly on effector immune cells (e.g., T and NK cells), the blockade of both these molecules have shown to reprogram myeloid biology and to bear therapeutic implications [129,130]. Interestingly, MDSCs have also been identified to be a key mediator in conferring resistance to cancer immunotherapy [131]. While anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 therapy are often discussed interchangeably, literature is beginning to show differences in patient responses. Accordingly, research has shown a differential response to PD-1 blockade and PD-L1 blockade in myeloid cells, where the latter leads to more robust inflammatory responses including IL-18 production and inflammasome activation [132]. An understanding of how these responses differ in the context of reovirus therapy is required and will lead to a better approach to combination therapy.

Table 2.

List of clinical trials using reovirus in combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapies for various cancers.

| Trial | Reoviral Agent | ICB therapy | Phase (s) | Cancer (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | Target | ||||

| NCT03723915 | Pelareorep | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | II | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Pancreatic cancer |

| NCT03605719 | Pelareorep | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Recurrent Plasma Cell Myeloma |

| NCT04102618 | Pelareorep | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | I | Breast cancer |

| NCT02620423 | Reolysin | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma |

| NCT04445844 | Pelareorep | Retifanlimab | PD-1 | II | Breast cancers |

| NCT04215146 | Pelareorep | Avelumab | PD-L1 | II | Metastatic breast cancer |

Table 3.

List of clinical trials using OVs in combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapies for various cancers.

| Trial | Virus Type | OV Agent | ICB Therapy | Phase (s) | Cancer (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | Target | |||||

| NCT03004183 | Adenovirus | ADV/HSVtk | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | II | Metastatic NSCLC, Metastatic TNBC |

| NCT02798406 | Adenovirus | DNX-2401 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | II | Glioblastoma, Gliosarcoma |

| NCT03003676 | Adenovirus | ONCOS-102 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced/unresectable melanoma progressing after PD-1 blockade |

| NCT03408587 | Coxsackie | CAVATAK | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | Ib | Uveal Melanoma with Liver Metastases |

| NCT02565992 | Coxsackie | CAVATAK | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced Melanoma |

| NCT02824965 | Coxsackie | CAVATAK | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I, II | Advanced NSCLC |

| NCT03153085 | HSV | HF10 (TBI-1401) | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | II | Unresectable/Metastatic Melanoma |

| NCT02272855 | HSV | HF10 (TBI-1401) | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | II | Unresectable/Metastatic Melanoma |

| NCT03259425 | HSV | HF10 (TBI-1401) | Nivolumab | PD-1 | II | Resectable Stage IIIB/C, IV Melanoma |

| NCT01740297 | HSV | T-Vec | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | Ib, II | Unresected Stage IIIb/IV melanoma |

| NCT02263508 | HSV | T-Vec | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Ib, III | Unresectable Stage IIIb/IV Melanoma |

| NCT02626000 | HSV | T-Vec | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Ib, III | Recurrent/Metastatic HNSCC |

| NCT02879760 | Maraba Virus | MG1-MAGEA3 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I, II | Previously treated NSCLC |

| NCT03206073 | Vaccinia | Pexa Vec | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I, II | Refractory Colorectal Cancer |

| Tremelimumab | CTLA-4 | |||||

| NCT02977156 | Vaccinia | Pexa Vec | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | I | Metastatic/Advanced Solid Tumors |

| NCT03071094 | Vaccinia | Pexa Vec | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I, IIa | Advanced HCC |

| NCT04185311 | HSV | T-Vec | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | I | Localized Breast Cancer |

| Nivolumab | PD-1 | |||||

| NCT03889275 | Newcastle disease virus | MEDI5395 | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I | Advanced Solid Tumors |

| NCT04301011 | Vaccinia | TBio-6517 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I, II | Triple Negative Breast Cancer Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer |

| NCT04735978 | HSV | RP3 | Anti-PD-1 mAb | PD-1 | I | Advanced Solid Tumor |

| NCT04348916 | HSV | ONCR-177 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced Solid Tumors |

| NCT03294083 | Vaccinia | Pexa Vec | Cemiplimab | PD-1 | I, II | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| NCT04755543 | HSV | OH2 | LP002 | PD-1 | I | Digestive System Neoplasms |

| NCT04386967 | HSV | OH2 | Keytruda | PD-1 | I, II | Solid Tumors, Melanoma |

| NCT04616443 | HSV | OH2 | HX008 | PD-1 | I, II | Melanoma |

| NCT03866525 | HSV | OH2 | HX008 | PD-1 | I, II | Solid Tumors, Gastrointestinal Cancer |

| NCT03206073 | Vaccinia | Pexa-Vec | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I, II | Colorectal Neoplasms |

| Tremelimumab | CTLA-4 | |||||

| NCT04665362 | Alphavirus | M1 | SHR-1210 | PD-1 | I | Advanced/Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| NCT04685499 | Adenovirus | OBP-301 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | II | HNSCC |

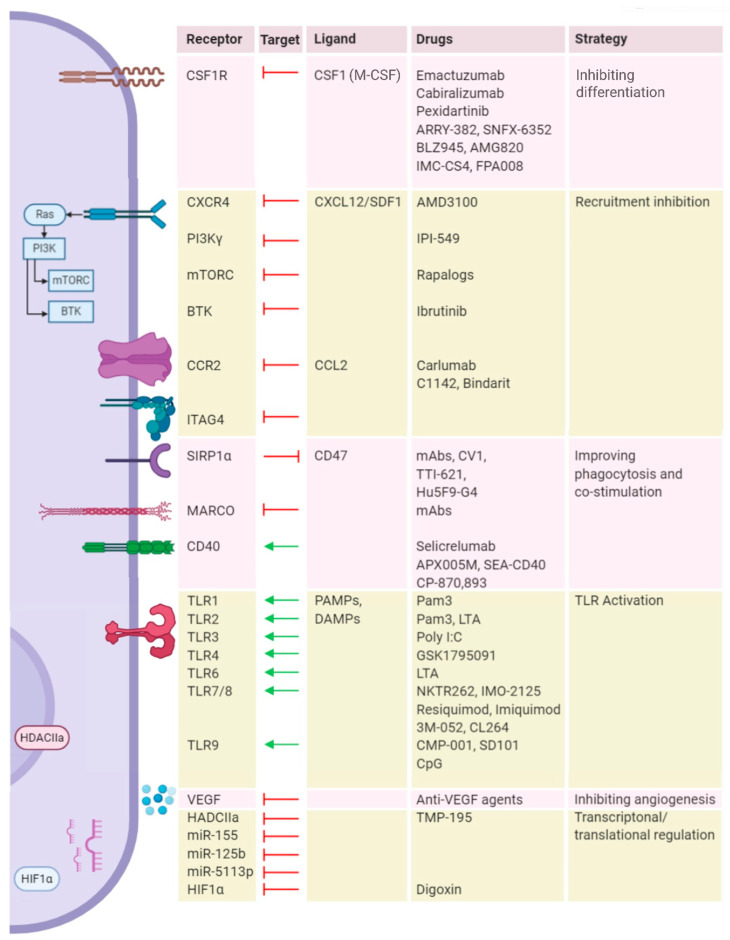

In addition to these mainstream ICBs, a range of other immune targets have been identified for reprogramming these suppressive myeloid cell types towards an antitumor phenotype. Here, CSF1R is the most widely explored target followed by TLR-4, TLR-7, TLR-8, TLR-9, CD40, CD47, and SIRPα [133,134,135]. Other targets such as BTK, CCR2, and RIP are also getting appreciated [99,136,137,138]. A list of clinical trials that exploit the targets for macrophage repolarization in synergy with ICB are listed in Table 4 and a list of immunological targets on macrophages are represented in Figure 3.

Table 4.

List of clinical trials targeting TAMs in combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapies for various cancers.

| Trial | TAM-Directed Agent | ICB Therapy | Phase (S) | Cancer (S) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | Target | Agent | Target | |||

| NCT02323191 | Emactuzumab | CSF1R | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | I | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors |

| NCT02880371 | ARRY-382 | CSF1R | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT02777710 | Pexidartinib | CSF1R | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I | Colorectal cancer; Pancreatic cancer; Metastatic cancer; Advanced cancer |

| NCT03238027 | SNFX-6352 | CSF1R | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I | Solid tumor; Metastatic tumor; Locally advanced malignant neoplasm; Unresectable malignant neoplasm |

| NCT02829723 | BLZ945 | CSF1R | PDR001 | PD-1 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT03158272 | Cabiralizumab | CSF1R | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced malignancies |

| NCT02713529 | AMG820 | CSF1R | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I/II | Pancreatic cancer; Colorectal cancer; Non-small cell lung cancer |

| NCT03123783 | APX005M | CD40 | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I/II | Non-small cell lung cancer; Metastatic melanoma |

| NCT02304393 | Selicrelumab | CD40 | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | I | Solid tumors |

| NCT02637531 | IPI-549 | PI3Kγ | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced solid tumor; non-small cell lung cancer; melanoma; breast cancer |

| NCT02890368 | TTI-621 | SIRPα | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Solid tumors; melanoma; merkel-cell carcinoma; squamous cell carcinoma; breast carcinoma |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | |||||

| Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | |||||

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 | |||||

| NCT03530683 | TTI-621 | SIRPα | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Lymphoma; myeloma |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | |||||

| NCT03681951 | GSK3145095 | RIP | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I/II | Neoplasms; pancreatic |

| NCT03435640 | NKTR262 | TLR7/8 | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I/II | Melanoma; merkel cell carcinoma; breast cancer; renal cell carcinoma; colorectal cancer |

| NCT02880371 | ARRY-382 | CSF1R | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | II | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT03153410 | IMC-CS4 | CSF1R | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | PDAC |

| NCT02526017 | FPA008 (Cabiralizumab) | CSF1R | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT03708224 | Emactuzumab | CSF1R | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | II | Advanced HNSCC |

| NCT03184870 | BMS-813160 | CCR2 | Nivolumab | PD-1 | I/II | PDAC, CRC |

| NCT03496662 | I/II | PDAC | ||||

| NCT03767582 | I/II | Locally advanced PDAC | ||||

| NCT03447314 | GSK1795091 | TLR4 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT03445533 | IMO-2125 | TLR7/8 | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | III | Metastatic melanoma |

| NCT02644967 | IMO-2125 | TLR7/8 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I/II | Metastatic melanoma |

| NCT02521870 | SD101 | TLR9 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Ib/II | Metastatic melanoma, recurrent HNSCC |

| NCT03007732 | I/II | Solid tumors | ||||

| NCT03618641 | CMP-001 | TLR9 | Nivolumab | PD-1 | II | Melanoma |

| NCT03507699 | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | ||||

| NCT02403271 | Ibrutinib | BTK | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | I/II | Relapsed or refractory solid tumors |

| NCT02376699 | SEA-CD40 | CD40 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | I | Solid tumors |

| NCT01103635 | CP-870, 893 | CD40 | Tremelimumab | CTLA-4 | I | Metastatic melanoma |

| NCT02760797 | R07009879 (Selicrelumab) | CD40 | Anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 | I | Advanced solid tumors |

| NCT02665416 | Bevacizumab/Vanucizumab | VEGF-A | I | Advanced solid tumors | ||

| NCT02953782 | Hu5F9-G4 | CD47 | Cetuximab | EGFR | I | Advanced solid malignancies and colorectal carcinoma |

Figure 3.

Current landscape of macrophage repolarization strategies. Various receptors, secretory molecules and regulatory pathways that skew macrophages to M2 state are lined on the left, and the respective therapeutic targets, their ligands, targeting strategies, and therapeutic agents are listed in the corresponding table on the right. Abbreviations: CSF1R: Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor; CSF1: Colony-stimulating factor 1; M-CSF: Macrophage colony-stimulating factor; CXCR4: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; CXCL12: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; SDF1: stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1); PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; mTORC: Mammalian target of rapamycin complex; BTK: Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CCR2: C-C chemokine receptor type 2; CCL2: C-C Motif chemokine ligand 2; ITAG: Integrin alpha gamma; SIRP1α: signal regulatory protein alpha; MARCO: Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure; TLR: Toll-like receptor; CD: Cluster of differentiation; PAMPs: Pathogen-activated molecular patterns; DAMPs: Damage-associated molecular patterns; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; HDACIIa: Histone deacetylase class IIa; HIF1α: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha.

5. Conclusions

Reovirus represents a promising oncolytic agent, and its ability to drive an adaptive antitumor T cell response makes it an increasingly attractive immunotherapeutic. However, the efficacy of reovirus-based therapies remains suboptimal due to the highly suppressive effects of the TME. In particular, tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell populations such TAMs and MDSCs significantly contribute to these immunosuppressive effects using a variety of processes, including the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, metabolic dysregulation, and T cell suppression. These TAM- and MDSC-based mechanisms hinder the efficacy of reovirus therapy but can be therapeutically targeted via blocking myeloid cell recruitment, depleting myeloid cell populations in the TME, reprogramming tumor or myeloid cell metabolism, and correcting aberrant cellular signaling pathways. The efficacy of many of these approaches is yet to be described in a reovirus-specific manner; therefore, further investigations testing the combination of reovirus and the TAM-/MDSC-targeting strategies promise to develop novel anticancer options.

Acknowledgments

Figures created with BioRender.com

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G., V.K., S.G.; data collection, V.K. and M.A.G.; writing, M.A.G. and V.K.; review and editing, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

V.K. is supported through the Cancer Research Training Program (CRTP) of the Beatrice Hunter Cancer Research Institute (BHCRI), with funds provided by the Motorcycle Ride for Dad through the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation (DMRF). M.A.G. is supported through the Cancer Research Training Program (CRTP) of Beatrice Hunter Cancer Research Institute (BHCRI), with funds provided by the QEII Health Sciences Centre Foundation and GIVETOLIVE Becky Beaton Award, the Nova Scotia Graduate Scholarship (NSGS), and Killam Doctoral Scholarship. S.G. is supported by research grants from Canadian Institutes for Health research (CIHR) and Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation (DMRF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteside T.L. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gujar S., Pol J.G., Kroemer G. Heating it up: Oncolytic viruses make tumors ‘hot’ and suitable for checkpoint blockade immunotherapies. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1442169. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1442169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy J.P., Kim Y., Clements D.R., Konda P., Schuster H., Kowalewski D.J., Paulo J.A., Cohen A.M., Stevanovic S., Gygi S.P., et al. Therapy-Induced MHC I Ligands Shape Neo-Antitumor CD8 T Cell Responses during Oncolytic Virus-Based Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Proteome Res. 2019;18:2666–2675. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gujar S., Bell J., Diallo J.S. SnapShot: Cancer Immunotherapy with Oncolytic Viruses. Cell. 2019;176:1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gujar S., Pol J.G., Kim Y., Lee P.W., Kroemer G. Antitumor Benefits of Antiviral Immunity: An Underappreciated Aspect of Oncolytic Virotherapies. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez H., Hagerling C., Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: From tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1267–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.314617.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maroun J., Muñoz-Alía M., Ammayappan A., Schulze A., Peng K.W., Russell S. Designing and building oncolytic viruses. Future Virol. 2017;12:193–213. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2016-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B., Wang X., Cheng P. Remodeling of Tumor Immune Microenvironment by Oncolytic Viruses. Front. Oncol. 2021;10:3478. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.561372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozak R., Hattin L., Biondi M., Corredor J., Walsh S., Xue-Zhong M., Manuel J., McGilvray I., Morgenstern J., Lusty E., et al. Replication and Oncolytic Activity of an Avian Orthoreovirus in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Viruses. 2017;9:90. doi: 10.3390/v9040090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai R., Meng G., Li Y., Wang W., Diao Y., Zhao S., Feng Q., Tang Y. The oncolytic efficacy and safety of avian reovirus and its dynamic distribution in infected mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019;244:983–991. doi: 10.1177/1535370219861928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmulevitz M., Marcato P., Lee P.W.K. Unshackling the links between reovirus oncolysis, Ras signaling, translational control and cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7720–7728. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gujar S., Dielschneider R., Clements D., Helson E., Shmulevitz M., Marcato P., Pan D., Pan L.Z., Ahn D.G., Alawadhi A., et al. Multifaceted therapeutic targeting of ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis through virus-induced immunomodulation. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:338–347. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gujar S.A., Lee P.W.K. Oncolytic virus-mediated reversal of impaired tumor antigen presentation. Front. Oncol. 2014;4 APR:77. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gujar S.A., Clements D., Dielschneider R., Helson E., Marcato P., Lee P.W.K. Gemcitabine enhances the efficacy of reovirus-based oncotherapy through anti-tumour immunological mechanisms. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;110:83–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gujar S.A., Marcato P., Pan D., Lee P.W.K. Reovirus virotherapy overrides tumor antigen presentation evasion and promotes protective antitumor immunity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2924–2933. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White C.L., Twigger K.R., Vidal L., De Bono J.S., Coffey M., Heinemann L., Morgan R., Merrick A., Errington F., Vile R.G., et al. Characterization of the adaptive and innate immune response to intravenous oncolytic reovirus (Dearing type 3) during a phase I clinical trial. Gene Ther. 2008;15:911–920. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginhoux F., Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: Developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirayama D., Iida T., Nakase H. The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;19:92. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J., Tang Z., Gao S., Li C., Feng Y., Zhou X. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: Recent Insights and Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:188. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacey D.C., Achuthan A., Fleetwood A.J., Dinh H., Roiniotis J., Scholz G.M., Chang M.W., Beckman S.K., Cook A.D., Hamilton J.A. Defining GM-CSF– and Macrophage-CSF–Dependent Macrophage Responses by In Vitro Models. J. Immunol. 2012;188:5752–5765. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez F.O., Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: Time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6 doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ushach I., Zlotnik A. Biological role of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) on cells of the myeloid lineage. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016;100:481–489. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RU0316-144R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton T.A., Zhao C., Pavicic P.G., Datta S. Myeloid colony-stimulating factors as regulators of macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:554. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viola A., Munari F., Sánchez-Rodríguez R., Scolaro T., Castegna A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1462. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neill L.A.J. A Metabolic Roadblock in Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016;17:625–626. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A., Marchesi F., Malesci A., Laghi L., Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:399–416. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fares C.M., Van Allen E.M., Drake C.G., Allison J.P., Hu-Lieskovan S. Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Why Does Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Not Work for All Patients? Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Annu. Meet. 2019;39:147–164. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_240837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pender A., Titmuss E., Pleasance E.D., Fan K.Y., Pearson H., Brown S.D., Grisdale C.J., Topham J.T., Shen Y., Bonakdar M., et al. Genome and transcriptome biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27:202–212. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayasingam S.D., Citartan M., Thang T.H., Mat Zin A.A., Ang K.C., Ch’ng E.S. Evaluating the Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages Into M1 and M2 Phenotypes in Human Cancer Tissue: Technicalities and Challenges in Routine Clinical Practice. Front. Oncol. 2020;9:1512. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue J., Schmidt S.V., Sander J., Draffehn A., Krebs W., Quester I., DeNardo D., Gohel T.D., Emde M., Schmidleithner L., et al. Transcriptome-Based Network Analysis Reveals a Spectrum Model of Human Macrophage Activation. Immunity. 2014;40:274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiss M., Van Gassen S., Movahedi K., Saeys Y., Laoui D. Myeloid cell heterogeneity in cancer: Not a single cell alike. Cell. Immunol. 2018;330:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locati M., Curtale G., Mantovani A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2020;15:123–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabrilovich D.I., Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid M.C., Franco I., Kang S.W., Hirsch E., Quilliam L.A., Varner J.A. PI3-Kinase γ Promotes Rap1a-Mediated Activation of Myeloid Cell Integrin α4β1, Leading to Tumor Inflammation and Growth. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesokhin A.M., Hohl T.M., Kitano S., Cortez C., Hirschhorn-Cymerman D., Avogadri F., Rizzuto G.A., Lazarus J.J., Pamer E.G., Houghton A.N., et al. Monocytic CCR2 + myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:876–886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Condamine T., Ramachandran I., Youn J.-I., Gabrilovich D.I. Regulation of Tumor Metastasis by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015;66:97–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051013-052304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabrilovich D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groth C., Hu X., Weber R., Fleming V., Altevogt P., Utikal J., Umansky V. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br. J. Cancer. 2019;120:16–25. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0333-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Condamine T., Gabrilovich D.I. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidov V., Jensen G., Mai S., Chen S.H., Pan P.Y. Analyzing One Cell at a TIME: Analysis of Myeloid Cell Contributions in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1842. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang P.F., Song S.Y., Wang T.J., Ji W.J., Li S.W., Liu N., Yan C.X. Prognostic role of pretreatment circulating MDSCs in patients with solid malignancies: A meta-analysis of 40 studies. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1494113. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1494113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fultang N., Li X., Li T., Chen Y.H. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Differentiation in Cancer: Transcriptional Regulators and Enhanceosome-Mediated Mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2021;11:3493. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.619253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beury D.W., Parker K.H., Nyandjo M., Sinha P., Carter K.A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Cross-talk among myeloid-derived suppressor cells, macrophages, and tumor cells impacts the inflammatory milieu of solid tumors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014;96:1109–1118. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0414-210R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murdoch C., Muthana M., Coffelt S.B., Lewis C.E. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petty A.J., Yang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: Implications in cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:289–302. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerriero J.L. Macrophages: The Road Less Traveled, Changing Anticancer Therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2018;24:472–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noy R., Pollard J.W. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vitale I., Manic G., Coussens L.M., Kroemer G., Galluzzi L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019;30:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelly P.M.A., Davison R.S., Bliss E., McGee J.O.D. Macrophages in human breast disease: A quantitative immunohistochemical study. Br. J. Cancer. 1988;57:174–177. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanada T., Nakagawa M., Emoto A., Nomura T., Nasu N., Nomura Y. Prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophage count in human bladder cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2000;7:263–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2000.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ciavarra R.P., Taylor L., Greene A.R., Yousefieh N., Horeth D., Van Rooijen N., Steel C., Gregory B., Birkenbach M., Sekellick M. Impact of macrophage and dendritic cell subset elimination on antiviral immunity, viral clearance and production of type 1 interferon. Virology. 2005;342:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murray P.J., Allen J.E., Biswas S.K., Fisher E.A., Gilroy D.W., Goerdt S., Gordon S., Hamilton J.A., Ivashkiv L.B., Lawrence T., et al. Macrophage Activation and Polarization: Nomenclature and Experimental Guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sica A., Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandura D.R., Baranov V.I., Ornatsky O.I., Antonov A., Kinach R., Lou X., Pavlov S., Vorobiev S., Dick J.E., Tanner S.D. Mass cytometry: Technique for real time single cell multitarget immunoassay based on inductively coupled plasma time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6813–6822. doi: 10.1021/ac901049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saeys Y., Van Gassen S., Lambrecht B.N. Computational flow cytometry: Helping to make sense of high-dimensional immunology data. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:449–462. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cassetta L., Fragkogianni S., Sims A.H., Swierczak A., Forrester L.M., Zhang H., Soong D.Y.H., Cotechini T., Anur P., Lin E.Y., et al. Human Tumor-Associated Macrophage and Monocyte Transcriptional Landscapes Reveal Cancer-Specific Reprogramming, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu X.D., Zhang J.B., Zhuang P.Y., Zhu H.G., Zhang W., Xiong Y.Q., Wu W.Z., Wang L., Tang Z.Y., Sun H.C. High expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in peritumoral liver tissue is associated with poor survival after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2707–2716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin E.Y., Nguyen A.V., Russell R.G., Pollard J.W. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:727–739. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruffell B., Affara N.I., Coussens L.M. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyckoff J., Wang W., Lin E.Y., Wang Y., Pixley F., Stanley E.R., Graf T., Pollard J.W., Segall J., Condeelis J. A paracrine loop between tumor cells and macrophages is required for tumor cell migration in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7022–7029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian B.Z., Pollard J.W. Macrophage Diversity Enhances Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizutani K., Sud S., McGregor N.A., Martinovski G., Rice B.T., Craig M.J., Varsos Z.S., Roca H., Pienta K.J. The chemokine CCL2 increases prostate tumor growth and bone metastasis through macrophage and osteoclast recruitment. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1235–1242. doi: 10.1593/neo.09988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kitamura T., Qian B.Z., Soong D., Cassetta L., Noy R., Sugano G., Kato Y., Li J., Pollard J.W. CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:1043–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Serafini P., Carbley R., Noonan K.A., Tan G., Bronte V., Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fridlender Z.G., Sun J., Kim S., Kapoor V., Cheng G., Ling L., Worthen G.S., Albelda S.M. Polarization of Tumor-Associated Neutrophil Phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiffry J., Thavornwatanayong T., Rao D., Fogel E.J., Saytoo D., Nahata R., Guzik H., Chaudhary I., Augustine T., Goel S., et al. Oncolytic reovirus (pelareorep) induces autophagy in KRAS-mutated colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27:865–876. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maitra R., Seetharam R., Tesfa L., Augustine T.A., Klampfer L., Coffey M.C., Mariadason J.M., Goel S. Oncolytic reovirus preferentially induces apoptosis in KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells, and synergizes with irinotecan. Oncotarget. 2014;5:2807–2819. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Villalona-Calero M.A., Lam E., Otterson G.A., Zhao W., Timmons M., Subramaniam D., Hade E.M., Gill G.M., Coffey M., Selvaggi G., et al. Oncolytic reovirus in combination with chemotherapy in metastatic or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer patients with KRAS-activated tumors. Cancer. 2016;122:875–883. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Danthi P., Guglielmi K.M., Kirchner E., Mainou B., Stehle T., Dermody T.S. Cell Entry by Non-Enveloped Viruses. Vol. 343. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. From Touchdown to Transcription: The Reovirus Cell Entry Pathway; pp. 91–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Müller L., Berkeley R., Barr T., Ilett E., Errington-Mais F. Past, Present and Future of Oncolytic Reovirus. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3219. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Aaronson S.A., Abrams J.M., Adam D., Agostinis P., Alnemri E.S., Altucci L., Amelio I., Andrews D.W., et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ikeda Y., Nishimura G., Yanoma S., Kubota A., Furukawa M., Tsukuda M. Reovirus oncolysis in human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31:407–412. doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(04)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuan J., Kroemer G. Alternative cell death mechanisms in development and beyond. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2592–2602. doi: 10.1101/gad.1984410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thirukkumaran C., Morris D.G. Oncolytic viral therapy using reovirus. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1317:187–223. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2727-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giacomantonio M.A., Sterea A.M., Kim Y., Paulo J.A., Clements D.R., Kennedy B.E., Bydoun M.J., Shi G., Waisman D.M., Gygi S.P., et al. Quantitative Proteome Responses to Oncolytic Reovirus in GM-CSF-and M-CSF-Differentiated Bone Marrow-Derived Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2020;19:708–718. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Clements D.R., Murphy J.P., Sterea A., Kennedy B.E., Kim Y., Helson E., Almasi S., Holay N., Konda P., Paulo J.A., et al. Quantitative Temporal in Vivo Proteomics Deciphers the Transition of Virus-Driven Myeloid Cells into M2 Macrophages. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:3391–3406. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fulci G., Breymann L., Gianni D., Kurozomi K., Rhee S.S., Yu J., Kaur B., Louis D.N., Weissleder R., Caligiuri M.A., et al. Cyclophosphamide enhances glioma virotherapy by inhibiting innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12873–12878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605496103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tan Z., Liu L., Chiu M.S., Cheung K.W., Yan C.W., Yu Z., Lee B.K., Liu W., Man K., Chen Z. Virotherapy-recruited PMN-MDSC infiltration of mesothelioma blocks antitumor CTL by IL-10-mediated dendritic cell suppression. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1518672. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1518672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kennedy B.E., Sadek M., Gujar S.A. Targeted Metabolic Reprogramming to Improve the Efficacy of Oncolytic Virus Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:1417–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Farhood B., Najafi M., Mortezaee K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:8509–8521. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clements D.R., Sterea A.M., Kim Y., Helson E., Dean C.A., Nunokawa A., Coyle K.M., Sharif T., Marcato P., Gujar S.A., et al. Newly Recruited CD11b +, GR-1 +, Ly6C high Myeloid Cells Augment Tumor-Associated Immunosuppression Immediately following the Therapeutic Administration of Oncolytic Reovirus. J. Immunol. 2015;194:4397–4412. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gujar S.A., Clements D., Lee P.W.K. Two is better than one: Complementing oncolytic virotherapy with gemcitabine to potentiate antitumor immune responses. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3 doi: 10.4161/onci.27622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katayama Y., Tachibana M., Kurisu N., Oya Y., Terasawa Y., Goda H., Kobiyama K., Ishii K.J., Akira S., Mizuguchi H., et al. Oncolytic Reovirus Inhibits Immunosuppressive Activity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in a TLR3-Dependent Manner. J. Immunol. 2018;200:2987–2999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parker J.N., Gillespie G.Y., Love C.E., Randall S., Whitley R.J., Markert J.M. Engineered herpes simplex virus expressing IL-12 in the treatment of experimental murine brain tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040557897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kleijn A., Kloezeman J., Treffers-Westerlaken E., Fulci G., Leenstra S., Dirven C., Debets R., Lamfers M. The In Vivo Therapeutic Efficacy of the Oncolytic Adenovirus Delta24-RGD Is Mediated by Tumor-Specific Immunity. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tan D.Q., Zhang L., Ohba K., Ye M., Ichiyama K., Yamamoto N. Macrophage response to oncolytic paramyxoviruses potentiates virus-mediated tumor cell killing. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016;46:919–928. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Esaki S., Goshima F., Kimura H., Murakami S., Nishiyama Y. Enhanced antitumoral activity of oncolytic herpes simplex virus with gemcitabine using colorectal tumor models. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132:1592–1601. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Togashi Y., Shitara K., Nishikawa H. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression—Implications for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019;16:356–371. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Siret C., Collignon A., Silvy F., Robert S., Cheyrol T., André P., Rigot V., Iovanna J., van de Pavert S., Lombardo D., et al. Deciphering the Crosstalk Between Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Regulatory T Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2020;10:3070. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lucca L.E., Dominguez-Villar M. Modulation of regulatory T cell function and stability by co-inhibitory receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:680–693. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Savage P.A., Klawon D.E.J., Miller C.H. Regulatory T Cell Development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020;38:421–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-100219-020937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Qian B.Z., Li J., Zhang H., Kitamura T., Zhang J., Campion L.R., Kaiser E.A., Snyder L.A., Pollard J.W. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ren G., Zhao X., Wang Y., Zhang X., Chen X., Xu C., Yuan Z.R., Roberts A.I., Zhang L., Zheng B., et al. CCR2-dependent recruitment of macrophages by tumor-educated mesenchymal stromal cells promotes tumor development and is mimicked by TNFα. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fridlender Z.G., Buchlis G., Kapoor V., Cheng G., Sun J., Singhal S., Crisanti C., Wang L.C.S., Heitjan D., Snyder L.A., et al. CCL2 blockade augments cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:109–118. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonapace L., Coissieux M.M., Wyckoff J., Mertz K.D., Varga Z., Junt T., Bentires-Alj M. Cessation of CCL2 inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting angiogenesis. Nature. 2014;515:130–133. doi: 10.1038/nature13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pathria P., Louis T.L., Varner J.A. Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:310–327. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hughes R., Qian B.Z., Rowan C., Muthana M., Keklikoglou I., Olson O.C., Tazzyman S., Danson S., Addison C., Clemons M., et al. Perivascular M2 macrophages stimulate tumor relapse after chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3479–3491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scala S. Molecular pathways: Targeting the CXCR4-CXCL12 Axis-Untapped potential in the tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:4278–4285. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Teicher B.A., Fricker S.P. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zheng X., Turkowski K., Mora J., Brüne B., Seeger W., Weigert A., Savai R. Redirecting tumor-associated macrophages to become tumoricidal effectors as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:48436–48452. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rogers T.L., Holen I. Tumour macrophages as potential targets of bisphosphonates. J. Transl. Med. 2011:9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Giraudo E., Inoue M., Hanahan D. An amino-bisphosphonate targets MMP-9–expressing macrophages and angiogenesis to impair cervical carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2004;114:623–633. doi: 10.1172/JCI200422087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Germano G., Frapolli R., Belgiovine C., Anselmo A., Pesce S., Liguori M., Erba E., Uboldi S., Zucchetti M., Pasqualini F., et al. Role of Macrophage Targeting in the Antitumor Activity of Trabectedin. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Denton N.L., Chen C.Y., Hutzen B., Currier M.A., Scott T., Nartker B., Leddon J.L., Wang P.Y., Srinivas R., Cassady K.A., et al. Myelolytic Treatments Enhance Oncolytic Herpes Virotherapy in Models of Ewing Sarcoma by Modulating the Immune Microenvironment. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2018;11:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fulci G., Dmitrieva N., Gianni D., Fontana E.J., Pan X., Lu Y., Kaufman C.S., Kaur B., Lawler S.E., Lee R.J., et al. Depletion of peripheral macrophages and brain microglia increases brain tumor titers of oncolytic viruses. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9398–9406. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.O’Neill L.A.J. A Broken Krebs Cycle in Macrophages. Immunity. 2015;42:393–394. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Van den Bossche J., O’Neill L.A., Menon D. Macrophage Immunometabolism: Where Are We (Going)? Trends Immunol. 2017;38:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.O’Neill L.A.J., Kishton R.J., Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:553–565. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jha A.K., Huang S.C.C., Sergushichev A., Lampropoulou V., Ivanova Y., Loginicheva E., Chmielewski K., Stewart K.M., Ashall J., Everts B., et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42:419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van den Bossche J., Baardman J., Otto N.A., van der Velden S., Neele A.E., van den Berg S.M., Luque-Martin R., Chen H.J., Boshuizen M.C.S., Ahmed M., et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016;17:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Huang S.C.C., Smith A.M., Everts B., Colonna M., Pearce E.L., Schilling J.D., Pearce E.J. Metabolic Reprogramming Mediated by the mTORC2-IRF4 Signaling Axis Is Essential for Macrophage Alternative Activation. Immunity. 2016;45:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kowal J., Kornete M., Joyce J.A. Re-education of macrophages as a therapeutic strategy in cancer. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:677–689. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barclay A.N., Van Den Berg T.K. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: Structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014;32:25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Weiskopf K., Ring A.M., Ho C.C.M., Volkmer J.P., Levin A.M., Volkmer A.K., Özkan E., Fernhoff N.B., Van De Rijn M., Weissman I.L., et al. Engineered SIRPα variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science. 2013;341:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1238856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shi G., Yang Q., Zhang Y., Jiang Q., Lin Y., Yang S., Wang H., Cheng L., Zhang X., Li Y., et al. Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment via Oncolytic Viruses and CSF-1R Inhibition Synergistically Enhances Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:244–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cerullo V., Diaconu I., Romano V., Hirvinen M., Ugolini M., Escutenaire S., Holm S.L., Kipar A., Kanerva A., Hemminki A. An oncolytic adenovirus enhanced for toll-like receptor 9 stimulation increases antitumor immune responses and tumor clearance. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:2076–2086. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Eriksson E., Moreno R., Milenova I., Liljenfeldt L., Dieterich L.C., Christiansson L., Karlsson H., Ullenhag G., Mangsbo S.M., Dimberg A., et al. Activation of myeloid and endothelial cells by CD40L gene therapy supports T-cell expansion and migration into the tumor microenvironment. Gene Ther. 2017;24:92–103. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kemp V., van den Wollenberg D.J.M., Camps M.G.M., van Hall T., Kinderman P., Pronk-van Montfoort N., Hoeben R.C. Arming oncolytic reovirus with GM-CSF gene to enhance immunity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2019;26:268–281. doi: 10.1038/s41417-018-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Breitbach C., Bell J.C., Hwang T.-H., Kirn D., Burke J. The emerging therapeutic potential of the oncolytic immunotherapeutic Pexa-Vec (JX-594) Oncolytic Virotherapy. 2015;4:25. doi: 10.2147/OV.S59640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Park S.H., Breitbach C.J., Lee J., Park J.O., Lim H.Y., Kang W.K., Moon A., Mun J.H., Sommermann E.M., Maruri Avidal L., et al. Phase 1b Trial of Biweekly Intravenous Pexa-Vec (JX-594), an Oncolytic and Immunotherapeutic Vaccinia Virus in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1532–1540. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cripe T.P., Ngo M.C., Geller J.I., Louis C.U., Currier M.A., Racadio J.M., Towbin A.J., Rooney C.M., Pelusio A., Moon A., et al. Phase 1 study of intratumoral Pexa-Vec (JX-594), an oncolytic and immunotherapeutic vaccinia virus, in pediatric cancer patients. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:602–608. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]