Abstract

Severe atopic dermatitis (AD) may lead to various complications such as hypoproteinaemia. We describe the case of a 7-month-old male infant with severe AD complicated with protein-losing enteropathy (PLE). He was diagnosed with AD at 2 months of age; however, because of familial steroid phobia, topical corticosteroids were not administered. At 7 months of age, he was admitted to our hospital for decreased feeding, diarrhoea, reduced urine volume and recurrent vomiting. Class 3 topical corticosteroid treatment was initiated. On day 3, eczema had almost resolved. However, serum protein levels had not improved; oliguria persisted and oedema worsened. Serum albumin scintigraphy revealed radioisotopes in the distal duodenum, leading to PLE diagnosis. Systemic prednisolone and albumin were administered, with no PLE relapse after discontinuation. To our knowledge, only two infant PLE cases associated with AD were reported to date. PLE should be considered in patients with severe AD and persistent hypoproteinaemia.

Keywords: dermatology, paediatrics

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disorder in infants and, if severe, may lead to complications such as growth failure, developmental retardation, hyponatraemia and hypoproteinaemia.1–4 Although the exact mechanism of hypoproteinaemia, which includes hypoalbuminaemia and hypogammaglobulinaemia, is unknown, it is considered to result from protein leakage through the inflamed skin and decreased protein synthesis caused by nutritional disorders. In most patients, hypoproteinaemia does not cause serious symptoms, such as hypovolaemic shock and severe bacterial infection. Serum protein levels can increase with the treatment of the skin condition with topical corticosteroids.1 2 Therefore, supplementation with albumin and globulin and treatment with systemic corticosteroids are usually unnecessary. We herein describe the case of a 7-month-old male infant with severe AD complicated by protein-losing enteropathy (PLE).

Case presentation

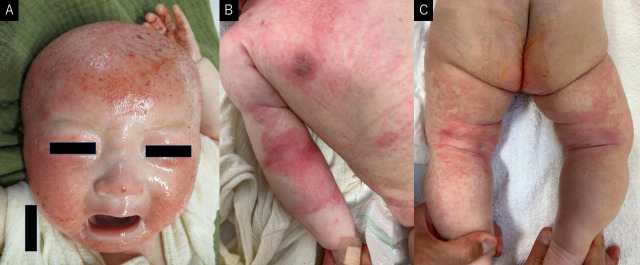

A 7-month-old male infant developed eczema at the age of 2 months, initially involving the face; however, it spread to the entire body within 1 month. The patient was diagnosed with AD at the age of 3 months; moisturising agents and topical corticosteroids were prescribed. However, owing to the steroid phobia of his mother and grandmother, these medications were not used. The infant did not undergo routine medical check-up and was unvaccinated. At the age of 6 months, solid diets (rice and vegetables) were initiated. At the age of 7 months, he was still being breast fed and consumed rice and vegetables only. He was admitted to our hospital with decreased feeding, diarrhoea (>10 episodes per day) and reduced urinary output. On admission, eczema over his head was severe; however, that on the rest of his body was mild and mainly localised to the precordial area, elbow and knee joints (eczema area and severity index score was 24) (figure 1). He looked pale and had mild oedema on his lower and upper extremities, and his abdomen was distended. His height and weight were 49.5 cm and 2665 g at birth, respectively. His height was 62.5 cm (−2.79 SD), and his weight was 5.8 kg (−2.97 SD) at admission (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Skin findings at the time of admission. (A) Erythema, scratches and bleeding are scattered on the head. (B) Erythemas are observed on precordium and right elbow joint. (C) Erythemas are observed on the knee joint and thigh.

Figure 2.

Growth chart of the patient. He was diagnosed with AD at the age of 3 months. At the time of admission at the age of 7 months, significant growth failure was observed. After treatment of AD and PLE, he has been steadily catching up. AD, atopic dermatitis; ADM, admission; PLE, protein-losing enteropathy.

). He looked pale and had mild oedema on his lower and upper extremities, and his abdomen was distended. His height and weight were 49.5 cm and 2665 g at birth, respectively. His height was 62.5 cm (−2.79 SD), and his weight was 5.8 kg (−2.97 SD) at admission (figure 2).

Investigations

Laboratory tests revealed the following: white cell, eosinophil, platelet counts of 22.2x109/L; 2.33x109/L (10.5%), and 949x109/L, respectively; haemoglobin level, 113 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase level, 69 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase level, 57 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase level, 504 IU/L; total protein level, 2.3 g/dL; albumin level, 1.0 g/dL; uric acid level, 2.3 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen level, 6 mg/L; creatinine level, 0.17 mg/dL; Na+ level, 133 mmol/L; K+ level, 4.8 mmol/L; C reactive protein level, 0.23 mg/dL; immunoglobulin G level, 167 mg/dL; immunoglobulin E (IgE) level, 8675 IU/mL; specific IgE antibody egg white, >100 IU/L; milk, 26.7 IU/L; wheat, 19.8 IU/L; soy, 71.1 IU/L; and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine level, 5665 pg/mL. Urine tested negative for protein. The rapid antigen test for norovirus and rotavirus was negative, with no evidence of pathogenic bacteria growth. Faecal analysis was negative for occult blood and eosinophils but positive for steatorrhea (Sudan Ⅲ staining). Faecal concentrations of alpha-1-antitrypsin could not be measured because we could not collect faeces for 24 hours. Abdominal ultrasonography showed ascites, dilation of the small intestine, thickening of the small intestinal wall and decreased intestinal peristalsis (figure 3). Cardiac ultrasonography showed no abnormal findings.

Figure 3.

Abdominal ultrasonography of an infant with atopic dermatitis, who developed protein-losing enteropathy, showing ascites, small intestinal dilatation, intestinal wall thickening and decreased intestinal peristalsis.

Differential diagnosis

PLE can be caused by various disorders, such as abnormal lymphatic vessels, abnormal mucosa of the intestine and increased intestinal capillary permeability. We speculated that PLE was caused by severe AD because PLE did not recur after successful cessation of systemic steroids. The only difference in the patient’s condition, including food intake, was AD resolution. It was a limitation of our case report that endoscopic and pathological findings were not accessible, and systemic corticosteroids were transiently administered. Moreover, besides eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (EGID), food allergens may be associated with PLE. We acknowledge that AD, as a cause of PLE, cannot be conclusively determined from a single case. Therefore, further studies are needed to corroborate our findings on PLE’s significance in severe AD cases.

Treatment

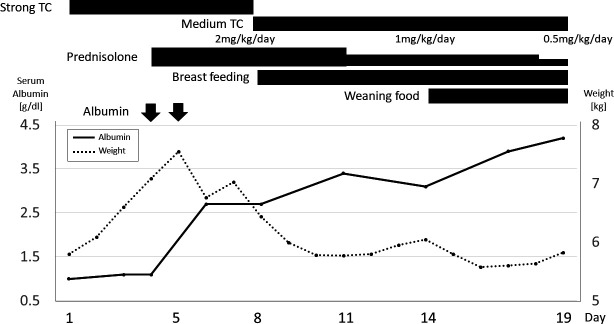

Because of recurrent vomiting, oral feeding was stopped, and intravenous fluids were administered. By the third day of treatment with a strong class (based on the classification in Japanese guidelines for AD5) topical corticosteroid (0.1% dexamethasone propionate) administration with fingertip-unit-based regimen,6 his eczema had almost resolved. However, the serum protein levels were not improved, oliguria persisted (0.55 mL/kg/hour) and oedema worsened. His body weight increased from 5.8 kg to 7.0 kg on day 4. 99mTc-human serum albumin scintigraphy revealed radioisotopes in the distal duodenum at 1 hour (figure 4). PLE was diagnosed based on these findings. Systemic prednisolone (2 mg/kg) and albumin (1 g/kg) were administered from day 4 onwards, gradually resolving hypoalbuminaemia and oedema. From the eighth day, the strong class (0.1% dexamethasone propionate) topical corticosteroids was replaced with a medium class (0.1% hydrocortisone butyrate). There were no maternal diet changes; breast feeding and weaning diet were reinitiated on days 8 and 14, respectively. Systemic prednisolone dosage was gradually tapered over 21 days, and PLE did not relapse after stopping medication (figure 5).

Figure 4.

99mTc-human serum albumin scintigraphy showing radioisotopes in the distal duodenum (arrow) at 1 hour.

Figure 5.

Post-admission disease course. TC application immediately improved eczema; however, hypoalbuminaemia persisted. Oliguria, oedema and body weight increased (from 5.8 to 7.0 kg on day 4). Systemic prednisolone and albumin were administered from day 4. Hypoalbuminaemia and oedema resolved gradually, and the patient was discharged on day 19. TC, topical corticosteroid.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s development and his growth course (height 71.2 cm and weight 8.6 kg at 1 year and 2 months old) improved without PLE relapse 10 months after resuming the previous diet (breast feeding without any changes of maternal diet) and eating other food items, such as wheat, soy, fish, and chickens.

Discussion

Hypoproteinaemia is often observed in severe infantile AD cases1–3 and usually does not cause serious symptoms.7 In most patients, hypoproteinaemia normally improves with the treatment of the skin condition using topical corticosteroids. While hypoproteinaemia is commonly considered to be caused by protein leakage from the inflamed skin, the association remains unclear. In our patient, despite improvement in the skin condition, hypoproteinaemia was not improved and symptoms, such as oedema and peripheral cyanosis, worsened. We suspected that protein leakage from the gastrointestinal tract occurred, and PLE was diagnosed based on gastrointestinal symptoms, steatorrhea, abdominal ultrasonography, and 99mTc-human serum albumin scintigraphy.

To the best of our knowledge, only two infant cases of PLE associated with AD have been reported to date, one of which was associated with EGID.8 9 Although EGID and food allergens may be associated with PLE in our patient, hypoproteinaemia did not improve after discontinuation of oral feeding and symptoms did not relapse after the resumption of his prehospitalisation diet (breast milk, rice and some vegetables). Therefore, EGID was considered unlikely.

The exact mechanism by which AD causes PLE remains unknown. However, AD may be associated with increased inflammation and permeability of the gastrointestinal tract. Yamada et al10 reported cases of inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract in patients with AD who had no gastrointestinal symptoms. Increased intestinal permeability in paediatric patients with AD has also been reported.11 Recently, Leyva-Castillo et al12 demonstrated that mechanical skin injury promotes intestinal permeability via activation of intestinal mast cells. These findings suggested that severe dermal inflammation may lead to gastrointestinal inflammation and increased permeability, resulting in protein leakage from the intestines.

This case report highlights a rare presentation of PLE associated with AD. PLE should be considered in patients with severe AD and persistent hypoproteinaemia. There may be some cases of gastrointestinal leakage associated with hypoproteinaemia to some extent. Further studies are recommended to establish the mechanism and treatment of PLE associated with AD.

Patient’s perspective.

My son used to have a strong itching caused by atopic dermatitis, but I’m glad that the topical corticosteroids improved the eczema and eliminated the itching. I was worried about the side effects of corticosteroids, but I was relieved that there were not any major side effects. After discharge, my son’s skin was in a good condition and his height and weight increased steadily.

Learning points.

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) should be considered in patients with severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and persistent hypoproteinaemia.

Hypoproteinaemia in severe infantile AD is usually not considered the cause of serious symptoms; however, hypoproetinaemia caused by PLE may lead to serious symptoms.

Systemic prednisolone and albumin supplementation should be considered when the symptoms caused by hypoproteinaemia are severe.

Footnotes

Contributors: YF collected and analysed the data and drafted and revised the initial manuscript. KN and SY interpreted all the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Katoh N, Hosoi H, Sugimoto T, et al. Features and prognoses of infantile patients with atopic dermatitis hospitalized for severe complications. J Dermatol 2006;33:827–32. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nomura I, Katsunuma T, Tomikawa M, et al. Hypoproteinemia in severe childhood atopic dermatitis: a serious complication. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2002;13:287–94. 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2002.01041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jo SY, Lee C-H, Jung W-J, et al. Common features of atopic dermatitis with hypoproteinemia. Korean J Pediatr 2018;61:348–54. 10.3345/kjp.2018.06324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi M, Takamasu T, Inuo C. Hyponatremia secondary to severe atopic dermatitis in early infancy. Pediatr Int 2019;61:544–50. 10.1111/ped.13865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katoh N, Ohya Y, Ikeda M, et al. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2020. Allergol Int 2020;69:356–69. 10.1016/j.alit.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit--a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991;16:444–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1991.tb01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capulong MC, Kimura K, Sakaguchi N, et al. Hypoalbuminemia, oliguria and peripheral cyanosis in an infant with severe atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1996;7:100–2. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1996.tb00114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang J-B, Kang YN, Won KS. Protein losing enteropathy in severe atopic dermatitis in an exclusively breast-fed infant. Pediatr Dermatol 2009;26:638–9. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins HR, Walker-Smith JA, Atherton DJ. Protein-Losing enteropathy in atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 1986;3:125–9. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada H, Izutani R, Chihara J, et al. Rantes mRNA expression in skin and colon of patients with atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1996;111:19–21. 10.1159/000237408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pike MG, Heddle RJ, Boulton P, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in atopic eczema. J Invest Dermatol 1986;86:101–4. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12284035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leyva-Castillo J-M, Galand C, Kam C, et al. Mechanical skin injury promotes food anaphylaxis by driving intestinal mast cell expansion. Immunity 2019;50:1262–75. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]