Introduction

Primary membranous nephropathy (pMN) is an autoimmune disease affecting kidney glomerulus and the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome (NS) in white adults without diabetes. The pathophysiology of pMN involves antibodies targeting podocyte antigens—mainly the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R1)—resulting in activation of the complement cascade.S1 The course of the disease is highly variable, ranging from spontaneous remission to progressive chronic kidney disease requiring renal replacement therapies. Antibody titers are correlated with disease activity and prognosis.S2,S3 Persistence of NS is associated with occurrence of end-stage renal disease.S4 Therefore, decreasing PLA2R1 antibody titers and achieving NS remission are important treatment goals. Rituximab—a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting CD20 on B cells—is an effective treatment in patients with pMN, allowing remission in 60% to 80% of cases.S5–S7 The treatment of rituximab-resistant pMN remains controversial and challenging.

Many causes could explain the lack of response after a first course of rituximab. As described with the use of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in other diseases, (i) some patients develop resistance as a result of neutralizing antidrug antibodies and (ii) some patients are undertreated owing to highly variable bioavailability. Indeed, rituximab bioavailability is significantly decreased in pMN compared with other non-nephrotic autoimmune diseases, because of rituximab wasting in the urine.1

Anti-rituximab antibodies have been detected in 23% to 43% of pMN patients treated with rituximab,2,3 and it is associated with a higher rate of relapse.3 Recently, new monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20 have been developed for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Obinutuzumab and ofatumumab are directed to a different epitope on CD20 and have higher affinity for CD20 than rituximab.S8,S9 Obinutuzumab is a humanized and glycoengineered type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Modification of the glycan tree structure at the Fc fragment of obinutuzumab leads to an increased affinity to FcgRIII and thereby potentiates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.S9 Ofatumumab is a human type I anti-CD20 antibody. Ofatumumab activates complement-dependent cytotoxicity more effectively than rituximab.S8 New monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20 have superior in vitro and in vivo B-cell cytotoxicity compared with rituximab.S8,S10 Contrary to rituximab, which expresses murine motifs, obinutuzumab and ofatumumab have a lower risk of immunogenicity.S11 Humanized or fully human antibodies have shown efficacy in some autoimmune or inflammatory diseases—such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic autoimmune diseases, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy—after the development of resistance to chimeric monoclonal antibodies following the appearance of antidrug antibodies.4, 5, 6 Therefore, the use of obinutuzumab or ofatumumab in treatment of pMN is an attractive option. In 2 recent case series with rituximab refractory pMN, obinutuzumab has been shown to be effective.7,8 However, the reason for treatment resistance was not analyzed (i.e. underdosing or antidrug antibodies), and therefore repeating rituximab injections could have been sufficient and cost effective. In a previous article,9 Dahan et al. described 10 patients who were refractory to an initial course of rituximab and who were re-treated with rituximab, resulting in remission in 8 of them. We previously showed that patients who required a second course of rituximab had significantly lower residual serum rituximab levels compared with patients who went into remission after a single course of rituximab.1 This finding supports the use of repeated doses of rituximab in some patients.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify predictors of rituximab resistance in order to personalize treatment. Here, we describe 8 patients with PLA2R1-associated pMN who were refractory to initial rituximab therapy (i.e., patients who do not achieve clinical and/or immunologic remission after a first rituximab course) whose therapeutic management was based on immunomonitoring of serum antidrug antibodies. Four of these patients were refractory to rituximab because of the development of anti-rituximab antibodies and were successfully treated with obinutuzumab or ofatumumab. The remaining 4, who did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies, responded effectively to repeated rituximab injections.

Case Presentations

Patients With Anti-Rituximab Antibodies

Case 1

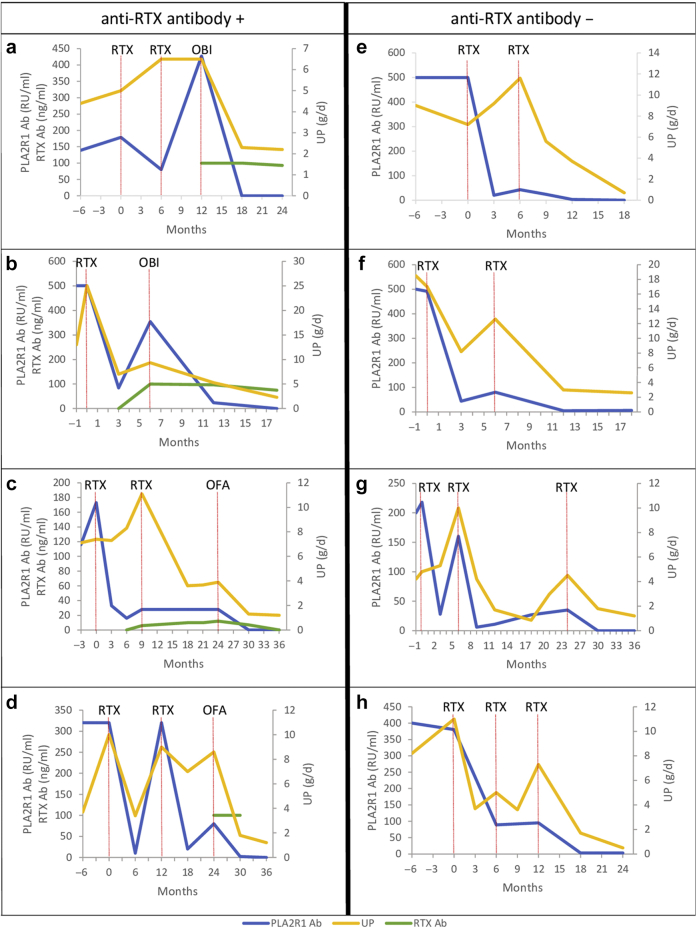

A 27-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. Eighteen months after diagnosis, no remission was observed with high PLA2R1 antibody titer. He was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusion, no remission was achieved and the patient was re-treated with rituximab (1 g administered intravenously). Six months after the last rituximab infusion, he had persistent NS with increased PLA2R1 antibody titer and the appearance of anti-rituximab antibodies with a titer greater than 100 ng/ml. Therefore, he was treated with obinutuzumab (100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2, and 1 g on day 8 intravenously). Six months after obinutuzumab infusions, the patient achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission. At last follow-up, 1 year after obinutuzumab infusions, the patient remained in immunologic and clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1a).

Table 1.

Change in laboratory values from first rituximab treatment (M0) to 36 months (M36) after first rituximab treatment

| Time (months) | Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 179 | 500 | 173 | 320 | 500 | 491 | 218 | 380 |

| UP (g/d) | 5 | 25 | 7.4 | 10 | 7.2 | 17 | 4.8 | 11 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | NA | 265 | NA | 21 | 402 | 668 | 157 | 86 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Treatment | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | |

| M3 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | NA | 84 | 33 | NA | 20 | 44 | 28 | NA |

| UP (g/d) | NA | 7 | 7.3 | NA | 9.2 | 8.2 | 5.3 | 3.7 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | NA | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 54 | NA | 1 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | NA | <5 | NA | NA | <5 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Treatment | |||||||||

| M6 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 80 | 354 | 16 | 10 | 43 | 80 | 160 | 89 |

| UP (g/d) | 6.5 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 3.4 | 11.6 | 12.6 | 10 | 5 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 35 | 57 | 3 | 0 | 50 | 158 | NA | 7 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | NA | >100 | <5 | NA | <5 | <5 | <5 | <5 | |

| Treatment | RTX | OBI | RTX | RTX | RTX | RTX | |||

| M9 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | NA | NA | 28 | NA | 24 | NA | 6 | NA |

| UP (g/d) | NA | NA | 11.1 | NA | 5.6 | NA | 4.2 | 3.6 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | NA | 0 | 57 | NA | NA | NA | 14 | 0 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | NA | NA | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Treatment | RTX | ||||||||

| M12 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 427 | 24 | NA | 320 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 95 |

| UP (g/d) | 6.5 | 5.3 | NA | 9 | 3.7 | 3 | 1.7 | 7.3 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 96 | 0 | NA | 18 | 1 | 4 | 27 | 2 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | >100 | 97 | NA | NA | <5 | NA | <5 | <5 | |

| Treatment | OBI | RTX | RTX | ||||||

| M18 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 0 | 0 | NA | 20 | 0 | 6 | 27 | 3 |

| UP (g/d) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 7 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.85 | 1.7 | |

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 45 | 0 | |

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | >100 | 75 | 10 | NA | < 5 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Treatment | |||||||||

| M24 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 0 | 28 | 80 | 35 | 3 | |||

| UP (g/d) | 2.2 | 3.9 | 8.6 | 4.5 | 0.5 | ||||

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 1 | 135 | NA | 77 | 0 | ||||

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | 93 | 12 | >100 | <5 | <5 | ||||

| Treatment | OFA | OFA | RTX | ||||||

| M30 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| UP (g/d) | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.8 | ||||||

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 0 | NA | 1 | ||||||

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | 7 | > 100 | NA | ||||||

| Treatment | |||||||||

| M36 | PLA2R1 Ab titer (RU/ml) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| UP (g/d) | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | ||||||

| CD19+ cells (cells/μl) | 0 | NA | 0 | ||||||

| RTX Ab titer (ng/ml) | <5 | NA | <5 | ||||||

| Treatment |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; NA, not available; OBI, obinutuzumab; OFA, ofatumumab; PLA2R1 Ab, phospholipase A2 receptor antibody; RTX, rituximab; RTX Ab, anti-rituximab antibody; UP, 24-hour urinary protein excretion.

Total IgG anti-PLA2R1 level was measured by ELISA (EUROIMMUN, Germany).

Anti-rituximab antibodies were detected by ELISA (LISA-TRACKER; Theradiag Croissy Beaubourg, France). The limit of detection for anti-rituximab antibodies defined by the manufacturer was 5 ng/ml.

Figure 1.

Twenty-four-hour urinary protein excretion, phospholipase A2 receptor antibody titer, and anti-rituximab antibody titer trends in relation to the treatments in (a) case 1, (b) case 2, (c) case 3, (d) case 4, (e) case 5, (f) case 6, (g) case 7, and (h) case 8. Anti-RTX antibody +, patients with anti-rituximab antibodies; Anti-RTX antibody –, patients without anti-rituximab antibodies; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OBI, obinutuzumab; OFA, ofatumumab; PLA2R1 Ab, phospholipase A2 receptor antibody; RTX, rituximab; RTX Ab, anti-rituximab antibody; UP, 24-hour urinary protein excretion. Total IgG anti-PLA2R1 level was measured by ELISA (EUROIMMUN, Germany). Anti-rituximab antibodies were detected by ELISA (LISA-TRACKER; Theradiag Croissy Beaubourg, France). The limit of detection for anti-rituximab antibodies defined by the manufacturer was 5 ng/ml.

Case 2

A 64-year-old woman was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. She had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. She was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. One month after initial therapy, owing to progressive impaired renal function with heavy proteinuria and persistently high PLA2R1 antibody titer, she was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusions, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed and anti-rituximab antibodies appeared with a titer greater than 100 ng/ml. Therefore, she was treated with obinutuzumab (100 mg intravenously on day 1, 900 mg intravenously on day 2, and 1 g intravenously on day 8). At last follow-up, 1 year after obinutuzumab infusions, she achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1b).

Case 3

A 54-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS and pulmonary embolism. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. Three months after initial therapy, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed. He was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Nine months after rituximab infusions, he had persistent NS and detectable PLA2R1 antibodies. The patient was re-treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). At that time, anti-rituximab antibodies were at the limit of detection threshold. Fifteen months after the second rituximab infusion, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed with an anti-rituximab antibody titer of 12 ng/ml. Therefore, he was treated with ofatumumab (300 mg on day 1 and 1 g on day 8 administered intravenously). Six months after the infusions, the patient achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1c). At last follow-up, 2 years after ofatumumab infusions, the patient remained in immunologic remission and in partial remission of NS.

Case 4

A 70-year-old woman was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. She had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. Initially, she was treated with supportive therapy alone. After 10 months, tacrolimus was added. Two months later, tacrolimus was discontinued because of impaired kidney function and she was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). One year after rituximab infusions, proteinuria and PLA2R1 antibody titer increased. Therefore, a new course of rituximab was started (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). One year after the second rituximab infusions, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed and anti-rituximab antibodies appeared with a titer greater than 100 ng/ml. Therefore, she was treated with ofatumumab (300 mg on day 1 and 1 g on day 8 administered intravenously). Six months after ofatumumab infusions, she achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1d). At last follow-up, 2 years after ofatumumab infusions, she achieved complete clinical remission of NS.

Patients Without Anti-Rituximab Antibodies

Case 5

A 34-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. Six months after diagnosis, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed. He was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusion, he did not achieve remission and was re-treated with rituximab (1 g administered intravenously). He achieved immunologic remission 6 months after the last rituximab infusion and clinical remission at last follow-up, 1 year after the last rituximab infusion (Table 1 and Figure 1e). The patient did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies during follow-up.

Case 6

A 58-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS and pulmonary embolism. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. One month after initial therapy, because of heavy proteinuria and persistently high PLA2R1 antibody titer, he was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusion, he did not achieve remission and was re-treated with rituximab (1 g administered intravenously). Six months after the last rituximab infusion, he achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission. At last follow-up, 1 year after the last rituximab infusion, the patient remained in immunologic and clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1f). The patient did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies during follow-up.

Case 7

A 53-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. One month after initial therapy, because of progressive impaired renal function with heavy proteinuria and persistently high PLA2R1 antibody titer, the patient was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusion, he did not achieve remission and was re-treated with rituximab (1 g administered intravenously). Six months after the last rituximab infusion, he achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission. However, 1 year later pMN relapsed and he was re-treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart), achieving immunologic remission and partial clinical remission 6 months later. At last follow-up, 1 year after the last rituximab infusions, the patient remained in immunologic remission and in partial remission of NS (Table 1 and Figure 1g). The patient did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies during follow-up.

Case 8

A 73-year-old man was diagnosed with PLA2R1-associated pMN after presenting with NS. He had PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain. He was initially treated with supportive therapy alone. Twelve months after initial therapy, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed and the patient was treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after rituximab infusions, no clinical or immunologic remission was observed and he was re-treated with rituximab (1 g administered intravenously). Six months after the last rituximab infusion, he did not achieve remission and was re-treated with 2 doses of rituximab (1 g each administered intravenously 2 weeks apart). Six months after the last rituximab infusions, he achieved immunologic remission and partial clinical remission. At last follow-up, 1 year after the last rituximab infusion, the patient remained in immunologic remission and achieved complete clinical remission (Table 1 and Figure 1h). The patient did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies during follow-up.

Discussion

We report 8 patients with PLA2R1-associated pMN who were refractory to a first rituximab course (i.e., patients who do not achieve clinical and/or immunologic remission). The management of these patients was guided by anti-rituximab antibody assay. Four patients had anti-rituximab antibodies and were resistant to rituximab. These patients entered into remission only after a course of obinutuzumab or ofatumumab. The remaining 4 did not develop anti-rituximab antibodies and were successfully treated with repeated doses of rituximab. Interestingly, all of these 8 patients had high anti-PLA2R1 antibody titers and PLA2R1 epitope spreading beyond the CysR domain at diagnosis, previously described as risk factors of treatment resistance.S3,S12,S13

Anti-rituximab antibodies are not uncommon, because 23% to 43% of pMN patients treated with rituximab developed anti-rituximab antibodies during follow-up.2,3 These antibodies neutralized rituximab activity in 80% of patients resulting in faster B-cell reconstitution and a higher rate of relapse.3 However, rituximab neutralization assay with anti-rituximab antibodies is not routinely available and therefore has not been performed in these patients.

The effectiveness of rituximab depends on the serum level of free rituximab. In patients with anti-rituximab antibodies, the efficacy of rituximab depends on a balance between antibody titer and the amount of free rituximab. The development of anti-rituximab antibodies in patients is therefore not necessarily associated with treatment failure, but is associated with a higher risk of treatment failure than patients without anti-rituximab antibodies. Furthermore, because the anti-rituximab antibody assay only detects free anti-rituximab antibodies (i.e., not bound to rituximab), the detection of anti-rituximab antibodies must be systematically considered as a risk factor for nonresponse to rituximab and therapeutic failure, whatever the titer.

We previously showed that anti-rituximab antibodies cross-reacted with obinutuzumab or ofatumumab in only 20% of patients.3 We here have shown that treatment with obinutuzumab or ofatumumab resulted in immunologic and clinical remission in all patients with anti-rituximab antibodies. Obinutuzumab or ofatumumab were well tolerated, and none of the patients had any serious adverse reactions. The use of these new monoclonal antibodies is therefore an interesting therapeutic perspective in patients who develop anti-rituximab antibodies.

However, systematic use of obinutuzumab or ofatumumab in patients who do not respond to rituximab, without testing for anti-rituximab antibodies, may not be appropriate. Indeed, although humanized or human anti-CD20 are more effective in blocking B cells in vitro than rituximab, randomized controlled trials comparing ofatumumab or obinutuzumab to rituximab in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma have not found superiority of these new monoclonal antibodies over rituximab.S14,S15 In primary multidrug-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children, a dose of ofatumumab similar to the one we have used (1 infusion of 1500 mg/1.73 m2) has not been shown to be effective in achieving remission whereas a higher dose (10,300 mg/1.73 m2 in 6 infusions) was more effective.S16,S17 Moreover, there is a large interindividual variability, and many factors may modify rituximab response.1 In the case of nephrotic patients, rituximab can be quickly eliminated in the urine.1 Interestingly, the 4 patients who responded to repeated injections of rituximab had undetectable residual serum rituximab levels 3 months after the first treatment injection. As we have shown here, clinical and immunological remission can be achieved with repeated injections of rituximab in the absence of anti-rituximab antibodies. Therefore, obinutuzumab and ofatumumab should be reserved only for patients with anti-rituximab antibodies.

In PLA2R1-associated pMN treated with rituximab, anti-rituximab antibodies might be a useful biomarker to predict clinical outcomes in addition to CD19+ cell count monitoring, monitoring of rituximab residual serum levels 3 months after rituximab injection,1 anti-PLA2R1 antibody titer at diagnosis,S12 and PLA2R1 epitope spreading at diagnosis.S13

Conclusion

In summary, in rituximab-resistant pMN or pMN relapsing after rituximab, anti-rituximab antibodies should be monitored (Table 2). Screening for anti-rituximab antibodies in these patients could help to select those who are likely to fail to respond to a new course of rituximab. These patients could then benefit from treatment with obinutuzumab or ofatumumab. However, randomized and well-powered clinical trials are needed to develop personalized therapeutic strategies in pMN based on anti-rituximab antibody screening and to evaluate the efficacy and the optimal dose of humanized or human anti-CD20 in patients with pMN who develop anti-rituximab antibodies.

Table 2.

Teaching points

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

pMN, primary membranous nephropathy.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary References.

References

- 1.Boyer-Suavet S., Andreani M., Cremoni M. Rituximab bioavailability in primary membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:1423–1425. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fervenza F.C., Cosio F.G., Erickson S.B. Rituximab treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2008;73:117–125. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyer-Suavet S., Andreani M., Lateb M. Neutralizing anti-rituximab antibodies and relapse in membranous nephropathy treated with rituximab. Front Immunol. 2020;10:3069. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afif W., Loftus E.V., Faubion W.A. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1133–1139. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combier A., Nocturne G., Henry J. Immunization to rituximab is more frequent in systemic autoimmune diseases than in rheumatoid arthritis: ofatumumab as alternative therapy. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2020;59:1347–1354. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casertano S., Signoriello E., Rossi F. Ocrelizumab in a case of refractory chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy with anti-rituximab antibodies. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:2673–2675. doi: 10.1111/ene.14498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klomjit N., Fervenza F.C., Zand L. Successful treatment of patients with refractory PLA2R-associated membranous nephropathy with obinutuzumab: a report of 3 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:883–888. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.02.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sethi S., Kumar S., Lim K., Jordan S.C. Obinutuzumab is effective for the treatment of refractory membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1515–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahan K., Johannet C., Esteve E. Retreatment with rituximab for membranous nephropathy with persistently elevated titers of anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody. Kidney Int. 2019;95:233–234. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.