Abstract

Objective

This study aims to improve the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by evaluating RCTs of acupuncture for low back pain (LBP) based on the CONSORT and STRICTA statements.

Methods

Literature from the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Ovid, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), WanFang database, and Chongqing Weipu (VIP) was systematically searched from 2010 to 2020. The general characteristics and the overall quality score (OQS) of the literature were evaluated by two investigators. The agreement between investigators was calculated using Cohen’s kappa statistics.

Results

A total of 31 RCTs were extracted in the final analysis. Based on the CONSORT statement, the items “title and abstract”, “background and objectives”, “intervention”, “outcomes”, “statistical methods”, “baseline data”, “outcomes and estimation” and “interpretation” have a positive rate of greater than 80%. The items “implementation”, “generalizability” and “protocol” have a positive rate of less than 30%. Based on the STRICTA statement, the items “style of acupuncture”, “needle retention time”, “number of treatment sessions”, “frequency and duration of treatment” and “precise description of the control or comparator” have a positive rate of greater than 80%. The item “extent to which the treatment was varied” has a positive rate of less than 30%. The agreements among most items are determined to be moderate or good.

Conclusion

The reporting quality of RCTs of acupuncture for LBP is moderate. Researchers should rigidly follow the CONSORT and STRICTA statements to enhance the quality of their studies.

Keywords: acupuncture, quality of reporting, low back pain, CONSORT, STRICTA

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP), which is defined by an area of pain that is typically localized between the edge of the ribs and the crease of the hips,1 is a problematic symptom. Once someone has problems with any part of the spine or part attached to the spine, such as lumbar intervertebral discs, ligaments, fascia, and muscles, LBP can occur.2 The incidence of LBP was 7.3% globally in 2015,1 meaning that approximately 540 million people suffered from LBP. In addition, it has been reported that one out of every six patients suffering from musculoskeletal problems is diagnosed with LBP.3 Although the number of LBP patients is large, LBP is usually tolerable. The prognosis represents a threat to LBP patients. Disability, for example, is the worst prognosis of LBP, representing a heavy burden to families and society.4 Due to poor medical conditions and harsh working conditions, the incidence of LBP in low-income countries or regions is rather high.5 According to the guidelines of LBP,6 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NASIDs) are recommended as the first-line therapy. Acupuncture is also recommended. However, NASIDs might cause bleeding7 and lead to gastrointestinal damage.8 Thus, patients have to pay extra money for other medicines that can protect the gastrointestinal tract. Compared with NASIDs, acupuncture seems safer because it has been reported to have fewer adverse events.9 Currently, acupuncture is increasingly accepted as a complementary or alternative therapeutic method. In America, approximately 54% of the population uses complementary or alternative therapy, especially for LBP.10 In China, the use of acupuncture is even higher. Therefore, acupuncture for LBP has attracted the attention of researchers, so many trials have been performed.

Established in 1996 and updated in 2017, the Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT)11,12 has the goals of improving the transparency of trials and avoiding resource waste. The STandards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA)13,14 was established in 2002 and updated in 2010. As an extension of CONSORT for acupuncture, STRICTA has the goal of increasing the rigor of acupuncture trial design. To the best of our knowledge, there is no article evaluating the quality of acupuncture for LBP based on CONSORT and STRICTA statements. Based on the above two statements, this study evaluates the reporting quality of acupuncture for LBP.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

To identify all articles that studied the efficacy of acupuncture on LBP, the following databases were searched from January 2010 to December 2020: Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Ovid, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), WanFang database, and Chongqing Weipu (VIP). In particular, we found that the trend of published articles about LBP was obviously increasing in the pilot search. Therefore, we aimed to search articles in the last 10 years. The following search terms were used in Chinese and English: (Acupuncture OR Acupuncture therapy OR Electro-acupuncture OR Manual acupuncture OR Warming acupuncture OR Auricular acupuncture OR Ear acupuncture OR Thread embedding acupuncture OR Motion style acupuncture) AND (Low Back Pain OR Back Pain, Low OR Back Pain, Low OR Low Back Pain OR Pain, Low Back OR Pain, Low Back OR Lumbago OR Lower Back Pain OR Back Pain, Lower OR Back Pain, Lower OR Lower Back Pains OR Pain, Lower Back OR Pains, Lower Back OR Low Back Ache OR Ache, Low Back OR Aches, Low Back OR Back Ache, Low OR Back Aches, Low OR Low Back Aches OR Low Backache OR Backache, Low OR Backaches, Low OR Low Backaches OR Low Back Pain, Postural OR Postural Low Back Pain OR Low Back Pain, Posterior Compartment OR Low Back Pain, Recurrent OR Recurrent Low Back Pain OR Low Back Pain, Mechanical OR Mechanical Low Back Pain OR low back pain).

Included and Excluded Criteria

Types of Studies

We searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared acupuncture with at least one control strategy for the treatment of LBP. The intervention of the control group can be another form of acupuncture or conventional treatment. RCTs without available data for extraction were excluded.

Types of Participants

All LBP patients of any age, gender and ethnicity were eligible. The clinical diagnosis of LBP was followed by expert consensus based on the site, duration, frequency and severity of the pain, excluding pain from feverish illness or menstruation.15 Patients who suffered from LBP for at least 6 months with or without lumbar disc protrusion screened by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were included.

Types of Intervention

Different forms of acupuncture techniques or needles, such as manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture, warming acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, thread embedding acupuncture, and motion style acupuncture, were included. In particular, acupuncture plus cupping, moxibustion and Chinese medicine were not included in this research. The intervention in the experimental group was acupuncture alone or acupuncture combined with medication, which is similar to the control group. The control group used placebo acupuncture, sham acupuncture, no treatment or conventional treatment.

Placebo acupuncture means that a semiblunt retractable needle did touch but did not pierce the skin.16 Sham acupuncture refers to a needle set on nonacupuncture points or acupuncture points not related to LBP.17 A modified nonfunctioning electroacupuncture stimulator was used to contrast with real electroacupuncture.

Selection of Reports

First, two investigators (HLL and DLZ) preliminarily searched RCTs according to the title and abstract on their own. Second, the investigators read the full text of reports for further selection following rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, after inspecting the selected reports for consistency, the studies were moved into the specified folders with different labels (included, excluded, undecided). Another magisterial investigator (LXZ) made a final decision regarding whether the reports in the “undecided” folder were included.

Data Extraction

Two investigators (HLL and DLZ) used Microsoft Excel 2019 to record study information, including author, publication year, language of the article, number of participants, intervention and course of treatment, from the final selection of RCTs. If the information was missing, then “no mention” was recorded. The investigators checked the sheet for consistency. Another magisterial investigator (ZLX) determined how to resolve any discrepancies noted in the sheets.

Assessment of Reporting Quality

Two investigators (ZQX and YTW) scored the reporting quality of RCTs of acupuncture for LBP individually based on the CONSORT and STRICTA statements. Before assessment, two investigators had a complete understanding of these two standards. Each item was scored 1 if it was reported and 0 if it was not mentioned or unclear (see the details in the Supplementary Materials). To assess the agreement between two investigators, Cohen’s κ-statistic18 was calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). According to Cohen’s definition, agreement was evaluated as perfect if κ was >0.8, good if 0.6 < κ ≤ 0.8, moderate if 0.4 < κ ≤ 0.6, fair if 0.2 < κ ≤ 0.4, and poor if κ was ≤0.2.

Results

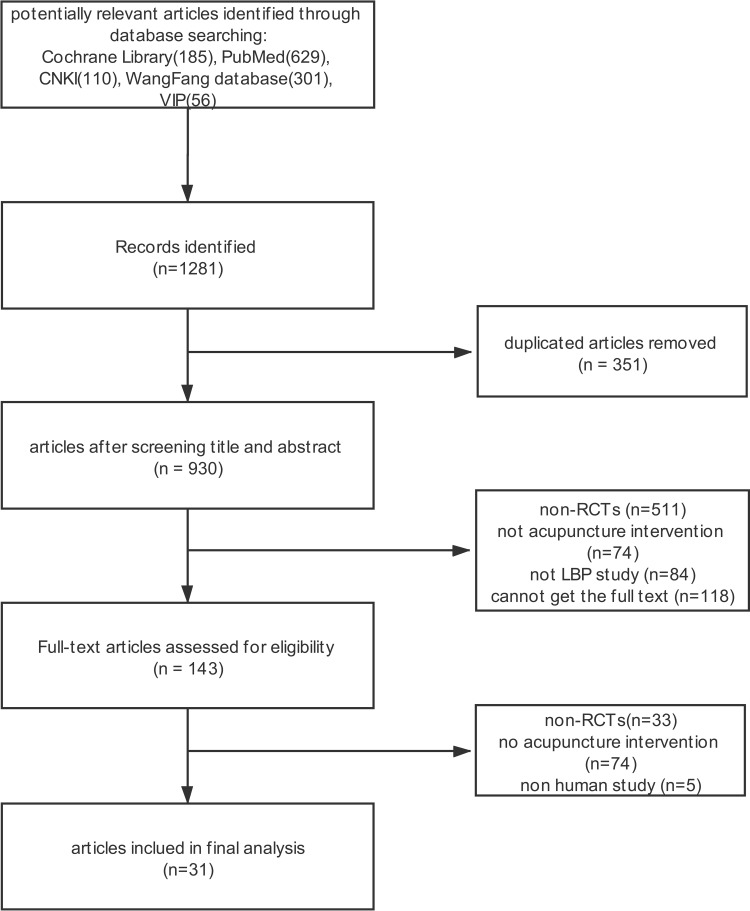

A total of potentially relevant RCTs were identified from 7 databases. After reading the title, abstract and full text, 31 RCTs were extracted for the final analysis. The whole selection process is depicted in Figure 1, and the general characteristics of the 31 included RCTs are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection process. 31 RCTs were extracted for the final analysis.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of the Included 31 Studies

| No. | Included Trials | Publication Language | No. of Participants | Intervention | Course of Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Control | Trial | Control | ||||

| 1 | Wasan 201019 | English | 21 | 19 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 21d |

| 2 | Chen 201020 | Chinese | 50 | 50 | Acupuncture | Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation | 5w |

| 3 | Su 201021 | Chinese | 30 | 30 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 1 session |

| 4 | Shankar 201122 | English | 30 | 30 | Electro-acupuncture | Valdecoxib | 3w |

| 5 | Hunter 201223 | English | 24 | 28 | Ear acupuncture + exercise | Exercise | 12w |

| 6 | Yun 201224 | English | 124 | 63 | Acupuncture | Usual care | 7w |

| 7 | Vas 201225 | English | 210 | 70 | Acupuncture | Conventional treatment | 4w |

| 8 | Cho 201317 | English | 65 | 65 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 6w |

| 9 | Shin 201326 | English | 29 | 29 | Motion style acupuncture | NSAIDs injection | 1 session |

| 10 | Wand 201327 | English | 25 | 25 | Sensory discrimination acupuncture | Usual acupuncture | 1 session |

| 11 | Weib 201328 | English | 79 | 77 | Acupuncture + standard rehabilitation programme | Standard rehabilitation programme | 21d |

| 12 | Hasegawa 201429 | English | 40 | 40 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 5 sessions |

| 13 | Seo 201730 | English | 27 | 27 | Bee venom acupuncture + Loxonin | Sham bee venom acupuncture + Loxonin | 3w |

| 14 | Kizhakkeveettil 201731 | English | 34 | 67 | Acupuncture | Spinal manipulative treatment/integrative care | 60d |

| 15 | Liu 201732 | English | 30 | 15 | 4/7 sessions acupuncture | 10 sessions acupuncture | 12w |

| 16 | Zhang 201733 | Chinese | 30 | 60 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | 1 session |

| 17 | Wu 201734 | Chinese | 30 | 30 | Internal heating acupuncture | Warm acupuncture | 3w |

| 18 | Zheng 201835 | English | 63 | 27 | Electroacupuncture/sham acupuncture | Pain medication management (opioid medications) | 10w |

| 19 | Lee 201836 | English | 20 | 20 | Thread embedding acupuncture | Acupuncture | 8w |

| 20 | Heo 201837 | English | 18 | 21 | Electroacupuncture + usual care | Usual care | 4w |

| 21 | Liu 201838 | Chinese | 42 | 42 | Internal heating acupuncture | Warm acupuncture | 10d |

| 22 | Luo 201939 | English | 104 | 48 | Acupuncture | Usual care | 7w |

| 23 | Vas 201940 | English | 165 | 55 | Ear acupuncture + standard obstetric care | Standard obstetric care | 2w |

| 24 | Nicolian 201941 | English | 96 | 103 | Acupuncture | Standard care | 4w |

| 25 | Li 201942 | Chinese | 49 | 49 | Tiaoshen acupuncture | Usual acupuncture | 2w |

| 26 | Comachio 202043 | English | 33 | 33 | Electro-acupuncture | Manual acupuncture | 6w |

| 27 | Bishop 202044 | English | 69 | 41 | Acupuncture + standard care | Standard care | 6w |

| 28 | Sung 202045 | English | 19 | 19 | Thread embedding acupuncture + acupuncture | Acupuncture | 8w |

| 29 | Li 202046 | Chinese | 30 | 30 | Six-directions acupuncture | Usual acupuncture | 13d |

| 30 | Wang 202047 | Chinese | 34 | 34 | Acupuncture at tendon lesions | Usual acupuncture | 4w |

| 31 | Yang 202048 | Chinese | 99 | 99 | Floating acupuncture | Usual acupuncture | 10d |

Year of Publication

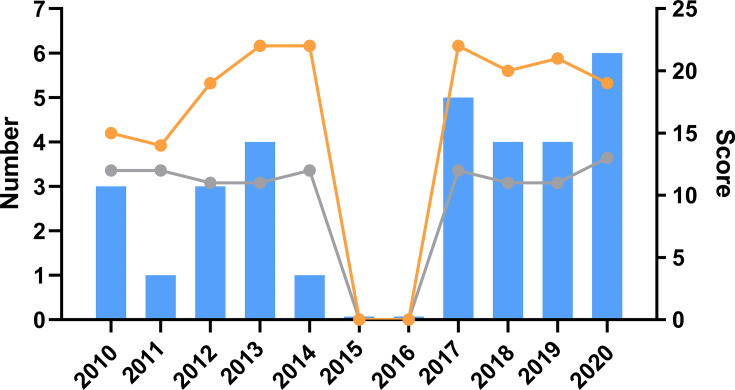

In total, 31 RCTs were published in the last 10 years from 2010 to 2020. The average scores of each year based on the CONSORT and STRICTA statements are presented in the line chart (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Year of publication. The blue bar is the number of RCTs published each year. The orange line is the median OQS with CONSORT statement of each year. The gray line is the median OQS with STRICTA statement of each year.

Publication Language and Nationality of Authors

Among the 31 RCTs, 22 RCTs (71%) were published in English, whereas 9 (29%) were published in Chinese. The authors of these articles were from America, Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Korea, New Zealand and Spain.

Invention

In the final extracted studies, different forms of acupuncture, including usual acupuncture (58.1%), electroacupuncture (12.9%), ear acupuncture (6.5%), internal heating acupuncture (6.5%), thread embedding acupuncture (6.5%), bee venom acupuncture (3.2%), floating acupuncture (3.2%) and motion style acupuncture (3.2%), were used.

Funding Resources

Sixteen studies (51.2%) reported their sources of funding. Nine (56.3%) received national funding, 2 (12.5%) received university funding, 4 (25.0%) received regional funding and 1 (6.3%) received personal funding. None of the included studies received funding from pharmaceutical companies.

Quality of Reporting

Reporting Quality Score Based on CONSORT Items

Based on the CONSORT statement, the data of overall quality of reporting are listed in Table 2. Among all included studies, the median overall quality score (OQS) was 20, ranging from 8 to 27. Good reporting included terms of “title and abstract”, “background and objectives”, “intervention”, “outcomes”, “statistical methods”, “baseline data”, “outcomes and estimation” and “interpretation” with a positive rate of greater than 80%. Nevertheless, poor reporting was noted for terms of “implementation”, “generalizability” and “protocol” with a positive rate of less than 30%. All items have moderate, good or perfect agreement, except for the items of “background and objectives-2.a” and “generalizability”, which have fair agreement. OQS details are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details of OQS Assessed with CONSORT Statement (n=31)

| Items | Items No. | Items Details | No. of Positive RCTs | % | Cohen’s κ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | ||||||

| 1.a | Identification as a randomized trial in the title | 29 | 93.55 | 0.78 | 0.38 to 1.00 | |

| 1.b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions; for specific guidance see CONSORT for Abstracts | 27 | 87.10 | 0.87 | 0.62 to 1.00 | |

| Introduction | ||||||

| Background and objectives | 2.a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | 25 | 80.65 | 0.37 | 0.05 to 0.69 |

| 2.b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | 29 | 93.55 | 0.48 | 0 to 1.00 | |

| Methods | ||||||

| Trial design | 3 | Description of trial design including allocation ratio | 26 | 83.87 | 0.76 | 0.46 to 1.00 |

| Participants | 4.a | Eligibility criteria for participants | 31 | 100.00 | 0.89 | 0.69 to 1.00 |

| 4.b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | 21 | 67.74 | 0.50 | 0.19 to 0.81 | |

| Interventions | 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication | 31 | 100.00 | 0.89 | 0.69 to 1.00 |

| Outcomes | 6 | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed | 31 | 100.00 | 0.89 | 0.69 to 1.00 |

| Sample size | 7 | How sample size was determined | 17 | 54.84 | 0.81 | 0.61 to 1.00 |

| Randomization | ||||||

| Sequence generation | 8.a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | 16 | 51.61 | 0.49 | 0.18 to 0.79 |

| 8.b | Type of randomization; details of any restriction | 12 | 38.71 | 0.59 | 0.31 to 0.88 | |

| Allocation concealment | 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence, describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | 12 | 38.71 | 0.52 | 0.21 to 0.83 |

| Implementation | 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | 8 | 25.81 | 0.41 | 0.07 to 0.74 |

| Blinding | 11 | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions and how | 14 | 45.16 | 0.62 | 0.41 to 0.84 |

| Statistical methods | 12 | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | 28 | 90.32 | 0.64 | 0.18 to 1.00 |

| Results | ||||||

| Participant flow | 13 | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome | 23 | 74.19 | 0.67 | 0.39 to 0.95 |

| Implementation of intervention | ||||||

| Recruitment | 14 | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | 18 | 58.06 | 0.74 | 0.49 to 0.98 |

| Baseline data | 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | 26 | 83.87 | 0.67 | 0.34 to 1.00 |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 | For each group, number of participants included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | 22 | 70.97 | 0.40 | 0.09 to 0.71 |

| Outcomes and estimation | 17 | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision | 31 | 100.00 | 1.00 | – |

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory | 23 | 74.19 | 0.67 | 0.37 to 0.96 |

| Harms | 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group; for specific guidance see CONSORT for Harms | 12 | 38.71 | 0.54 | 0.27 to 0.81 |

| Discussion | ||||||

| Limitations | 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | 20 | 64.52 | 0.45 | 0.04 to 0.85 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Generalizability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | 8 | 25.81 | 0.38 | 0.09 to 0.67 |

| Interpretation | 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | 30 | 96.77 | 0.73 | 0.46 to 1.00 |

| Registration | 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | 18 | 58.06 | 0.68 | 0.44 to 0.92 |

| Protocol | 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | 6 | 19.35 | 0.89 | 0.64 to 1.00 |

| Funding | 25 | Sources of funding and other support; role of funders | 20 | 64.52 | 0.87 | 0.70 to 1.00 |

Reporting Quality Score Based on STRICTA Items

Based on the STRICTA statement, the data of overall quality of reporting are listed in Table 3. Among all included studies, the median OQS was 12, ranging from 8 to 16. Good reporting was noted for the terms of “style of acupuncture”, “needle retention time”, “number of treatment sessions”, “frequency and duration of treatment” and “precise description of the control or comparator” with a positive rate of greater than 80%. Nevertheless, poor reporting was noted for the term “extent to which treatment was varied” with a positive rate of less than 30%. All items had moderate, good or perfect agreement. OQS details are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

The Details of OQS Assessed with STRICTA Statement (n=31)

| Items | Item Details | No. of Positive RCTs | % | Cohen’s κ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acupuncture rationale | 1a) Style of acupuncture | 31 | 100.00 | 1.00 | – |

| 1b) Reasoning for treatment provided | 24 | 77.42 | 1.00 | – | |

| 1c) Extent to which treatment was varied | 4 | 12.90 | 0.43 | 0 to 0.89 | |

| 2. Details of needling | 2a) Number of needle insertions per subject per session | 23 | 74.19 | 0.83 | 0.61 to 1.00 |

| 2b) Names of points used | 23 | 74.19 | 0.67 | 0.39 to 0.95 | |

| 2c) Depth of insertion | 17 | 54.84 | 0.74 | 0.52 to 0.97 | |

| 2d) Response sought | 16 | 51.61 | 0.81 | 0.61 to 1.00 | |

| 2e) Needle stimulation | 19 | 61.29 | 0.49 | 0.23 to 0.75 | |

| 2f) Needle retention time | 30 | 96.77 | 0.65 | 0.02 to 1.00 | |

| 2g) Needle type | 24 | 77.42 | 0.74 | 0.46 to 1.00 | |

| 3. Treatment regimen | 3a) Number of treatment sessions | 28 | 90.32 | 0.52 | 0.04 to 0.99 |

| 3b) Frequency and duration of treatment sessions | 29 | 93.55 | 0.48 | 0 to 1.00 | |

| 4. Other components of treatment | 4a) Details of other interventions administered to the acupuncture group | 22 | 70.97 | 0.53 | 0.21 to 0.86 |

| 4b) Setting and context of treatment | 12 | 38.71 | 0.79 | 0.57 to 1.00 | |

| 5. Practitioner background | 5) Description of participating acupuncturists | 13 | 41.94 | 0.48 | 0.18 to 0.78 |

| 6. Control or comparator interventions | 6a) Rationale for the control or comparator in the context of the research question, with sources that justify this choice | 20 | 64.52 | 0.86 | 0.67 to 1.00 |

| 6b) Precise description of the control or comparator | 25 | 80.65 | 0.59 | 0.23 to 0.95 |

Discussion

This study first showed the reporting quality of RCTs that assessed the efficacy of acupuncture for LBP, adhering strictly to the CONSORT and STRICTA statements. Good quality RCTs not only reduce the bias of the trial but also contribute to the development of guidelines.49 Therefore, a good quality study has positive meaning.

The OQS of RCTs based on the CONSORT statement was not satisfactory enough. Almost every included study prominently illustrated that the study was an RCT in the title. However, the positive rate of the items of randomization was low, and the positive rate for the item “implementation” was even less than 30%. Most of the studies stated that they allocated patients randomized but without details. The studies did not mention the method used to generate the random allocation sequence or the mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence. Moreover, only 8 RCTs (25.81%) reported the person who generated the random allocation sequence. Accurate randomization eliminates the selection bias to the maximum extent and ascertains how well the randomization materials are performed.50 Therefore, researchers should pay more attention to the randomization methodology to ensure that their study is randomized correctly and to improve the quality of the study.

Given the particularities of acupuncture, many problems still need to be solved when considering blindness. Although advanced placebo acupuncture needles51 that broke the stereotype that only naïve acupuncture studies can be double-blinded52 were invented, it is difficult to completely and simultaneously blind patients and intervenors.53 Therefore, most of the included RCTs blinded patients or investigators who analyzed the data. Despite the difficulties in blinding, researchers should make efforts employ blindness in the trials to eliminate the expectation bias that seems inevitable at present.

Due to the small sample size of the included RCTs, the positive rate of generalizability was less than 30%. This item is relatively subjective, and the agreement of the two investigators is low. Therefore, multicenter, large-scale RCTs are needed to improve generalizability.

To our surprise, only 6 RCTs (19.35%) reported that the protocol was accessed, whereas 18 RCTs (58.06%) reported their registration number. The importance of a protocol is that it describes the entire process and the details of a study. If one small step in the entire trial goes wrong, the whole trial may be worthless or might need to be performed again, wasting time and money. Magisterial experts can judge the feasibility of a study by reading the protocol and agree to the ethical assessment of the study. However, according to the results, the number of registered trials and trials with protocols that can be assessed is not equal. This finding indicates that some of the included trials might not have a rigorous design.

The OQS of RCTs based on the STRICTA statement do not reach satisfactory levels, especially for the item “extent to which the treatment was varied”. According to traditional Chinese medical theory,54 different syndromes require different treatments. This principle is also applicable in acupuncture. Therefore, LBP patients need personalized acupuncture therapeutic schedules. However, only 3 RCTs (9.68%) reported changes in acupuncture, and the remaining researchers spent more time on the acupuncture rationale. We also found that the OQS values of Chinese RCTs were greater than those of English RCTs based on the STRICTA statement. However, the OQS values of Chinese RCTs were lower than those of English RCTs based on the CONSORT statement. Given that acupuncture can be traced back over 3000 years in China, the Chinese formed a relatively perfect therapeutic system. Chinese researchers might think more apprehensively when making acupuncture schedules. However, regarding the standard trial design, Chinese researchers were less thoughtful than foreign researchers. We found that the OQS trend of each year was quite flat (Figure 2), and the average score of the included RCTs with STRICTA was 12 of 17, indicating that the reporting quality was always greater than moderate. Thus, we believe that spending more time on the acupuncture rationale is the key to enhancing the quality of acupuncture trials.

Although we systematically analyzed 31 RCTs, there are still some limitations in this study. Due to language barriers, we only included RCTs published in English and Chinese and excluded RCTs published in Korean or Japanese. Acupuncture is widely used in Korea and Japan, resulting in the loss of valuable data about the use of acupuncture for the treatment of LBP.

Conclusions

This study indicates that the reporting quality of RCTs that assessed the efficacy of acupuncture for LBP was moderate and needs further improvement to increase the level of evidence and guide clinical treatment better. In particular, the randomization methodology and acupuncture rationale should be explicitly explained in the article. These findings emphasize the need to improve the standard of operation. Therefore, we recommend that researchers draft acupuncture protocols rigidly based on the CONSORT and STRICTA statements to enhance the OQS of their studies, thereby convincing more people that acupuncture has good efficacy in the treatment of LBP.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (GZY-KJS-2020-072), the Science and Technology Department of Guangdong Province (2018-5).

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and Supplementary Information.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. In particular, Nanbu Wang, who has the overseas experience in Massachusetts General Hospital, polished up this article and edited the layout of this article. Thanks for her contribution.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hartvigsen J, Hancock M, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–2367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navani A, Manchikanti L, Albers S, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective use of biologics in the management of low back pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2019;22(1):S1–S74. doi: 10.36076/ppj/2019.22.s1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jöud A, Petersson I, Englund M. Low back pain: epidemiology of consultations. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(7):1084–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoy D, Smith E, Cross M, et al. Reflecting on the global burden of musculoskeletal conditions: lessons learnt from the global burden of disease 2010 study and the next steps forward. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):4–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qaseem A, Wilt T, Mclean R, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perahia D, Bangs M, Zhang Q, et al. The risk of bleeding with duloxetine treatment in patients who use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): analysis of placebo-controlled trials and post-marketing adverse event reports. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2013;5(1):211–219. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S45445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smecuol E, Bai J, Sugai E, et al. Acute gastrointestinal permeability responses to different non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gut. 2001;49(5):650–655. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.5.650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarkson C, O’mahony D, Jones D. Adverse event reporting in studies of penetrating acupuncture during pregnancy: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(5):453–464. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolsko P, Eisenberg D, Davis R, et al. Patterns and perceptions of care for treatment of back and neck pain: results of a national survey. Spine. 2003;28(3):292–298. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042225.88095.7C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540080059030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutron I, Altman D, Moher D, et al. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40–47. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macpherson H, Altman D, Hammerschlag R, et al. Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macpherson H, White A, Cummings M, et al. Standards for reporting interventions in controlled trials of acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9(4):246–249. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dionne C, Dunn K, Croft P, et al. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine. 2008;33(1):95–103. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e7f94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlaeger J, Takakura N, Yajima H, et al. Double-blind acupuncture needles: a multi-needle, multi-session randomized feasibility study. Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2018;4:72. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0265-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho Y, Song Y, Cha Y, et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a multicenter, randomized, patient-assessor blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Spine. 2013;38(7):549–557. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318275e601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen JA. Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasan A, Kong J, Pham L, et al. The impact of placebo, psychopathology, and expectations on the response to acupuncture needling in patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2010;11(6):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LX, Duan JF, Wang YQ, et al. A randomized controlled study of acupuncture combined with percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for chronic low back pain. J Cervicodynia Lumbodynia. 2010;31(02):137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su JT, Zhou QH, Li R, et al. Immediate analgesic effect of wrist-ankle acupuncture for acute lumbago:a randomized controlled trial. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. 2010;30(08):617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankar N, Thakur M, Tandon O, et al. Autonomic status and pain profile in patients of chronic low back pain and following electro acupuncture therapy: a randomized control trial. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;55(1):25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter R, Mcdonough S, Bradbury I, et al. Exercise and auricular acupuncture for chronic low-back pain: a feasibility randomized-controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(3):259–267. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182274018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun M, Shao Y, Zhang Y, et al. Hegu acupuncture for chronic low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(2):130–136. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vas J, Aranda J, Modesto M, et al. Acupuncture in patients with acute low back pain: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2012;153(9):1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin J, Ha I, Lee J, et al. Effects of motion style acupuncture treatment in acute low back pain patients with severe disability: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial. Pain. 2013;154(7):1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wand B, Abbaszadeh S, Smith A, et al. Acupuncture applied as a sensory discrimination training tool decreases movement-related pain in patients with chronic low back pain more than acupuncture alone: a randomised cross-over experiment. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(17):1085–1089. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss J, Quante S, Xue F, et al. Effectiveness and acceptance of acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(12):935–941. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasegawa T, Baptista A, De Souza M, et al. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, placebo trial. Acupuncture Med. 2014;32(2):109–115. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2013-010333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo B, Han K, Kwon O, et al. Efficacy of bee venom acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled trial. Toxins. 2017;9(11):361. doi: 10.3390/toxins9110361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kizhakkeveettil A, Rose K, Kadar G, et al. Integrative acupuncture and spinal manipulative therapy versus either alone for low back pain: a randomized controlled trial feasibility study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(3):201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Skinner M, Mcdonough S, et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled feasibility trial comparing treatment session numbers. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(12):1592–1603. doi: 10.1177/0269215517705690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XW, Ma LS, Han YY, et al. Needling point specificity for analgesic effect of wrist-ankle acupuncture on low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Shanghai J Trad Chin Med. 2017;51(04):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu H, Jin W, Zhou YM, et al. Low back pain of cold-dampness type treated with internal heating acupuncture needle: a randomized controlled trial. Pract Clin J Integr Trad Chin West Med. 2017;17(01):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Z, Gibson S, Helme R, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on opioid consumption in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2019;20(2):397–410. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H, Choi B, Jun S, et al. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):680. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3049-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heo I, Hwang M, Hwang E, et al. Electroacupuncture as a complement to usual care for patients with non-acute low back pain after back surgery: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e018464. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Fei L, Wang JH. Comparative study on the efficacy of internal heat acupuncture and warm acupuncture on osphyalgia of the Hanshi type. Clin J Chin Med. 2018;10(25):36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo Y, Yang M, Liu T, et al. Effect of hand-ear acupuncture on chronic low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Trad Chin Med. 2019;39(4):587–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vas J, Cintado M, Aranda-Regules J, et al. Effect of ear acupuncture on pregnancy-related pain in the lower back and posterior pelvic girdle: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(10):1307–1317. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicolian S, Butel T, Gambotti L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of acupuncture versus standard care for pelvic and low back pain in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li JX, Xie JJ, Guo XQ, et al. Effect of “Tiaoshen Acupuncture” on postpartum low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. 2019;39(01):24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Comachio J, Oliveira C, Silva I, et al. Effectiveness of manual and electrical acupuncture for chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2020;13(3):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bishop A, Ogollah R, Bartlam B, et al. Evaluating acupuncture and standard care for pregnant women with back pain: the EASE back pilot randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN49955124). Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2016;2(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0107-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sung W, Hong Y, Jeon S, et al. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture combined with acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded, multicenter clinical trial. Medicine. 2020;99(49):e22526. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li ZM, Bao WL. Clinical effect of small six directions-needling on nonspecific low back pain. J Kunming Med Univ. 2020;41(01):137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang LC, Dong BQ, Lin XX, et al. Randomized clinical control study on treatment of non-specific low back pain by acupuncture at tendon lesions and meridian points. J Pract Trad Chin Intern Med. 2020;34(03):13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang QY, Liao YM, Tan XZ, et al. A multi-center, randomized controlled study on the treatment of nonspecific low back pain with floating acupuncture. China Med Pharm. 2020;10(20):15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2; 2021. Available from: http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed April9, 2021.

- 50.Berger V, Bears J. When can a clinical trial be called ‘randomized’? Vaccine. 2003;21(5–6):468–472. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00475-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet. 1998;352(9125):364–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10471-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mark L. Double-blind studies of acupuncture. JAMA. 1973;225(12):1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.1973.03220400058020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vase L, Baram S, Takakura N, et al. Can acupuncture treatment be double-blinded? An evaluation of double-blind acupuncture treatment of postoperative pain. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun GR, Zheng HX. Basic theory of traditional Chinese medicine. China Press Trad Chin Med. 2017. [Google Scholar]