Abstract

RNA modification represents one of the most ubiquitous mechanisms of epigenetic regulation and plays an essential role in modulating cell proliferation, differentiation, fate determination, and other biological activities. At present, over 170 types of RNA modification have been discovered in messenger RNA (mRNA) and noncoding RNA (ncRNA). RNA methylation, as an abundant and widely studied epigenetic modification, is crucial for regulating various physiological or pathological states, especially immune responses. Considering the biological significance of T cells as a defense against viral infection and tumor challenge, in this review, we will summarize recent findings of how RNA methylation regulates T cell homeostasis and function, discuss the open questions in this rapidly expanding field of RNA modification, and provide the theoretical basis and potential therapeutic strategies involving targeting of RNA methylation to orchestrate beneficial T cell immune responses.

Keywords: RNA methylation, m6A, T cell, epigenetics, immune function

Introduction

Over 170 types of RNA modifications have been identified to date, which have allowed to expand the RNA code, giving rise to a new field called “RNA epigenetics” (1–3). Dynamic chemical modifications alter the structure and metabolism of coding and non-coding RNAs post-transcriptionally (1–3). As mass spectrometry and high throughput technology continue to be developed, these modifications can be studied more broadly and deeply. Among these modifications, RNA methylation is an important post-transcriptional regulation and comprises diverse forms of methylation, including N 6-methyladenosine (m6A), N 6-2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), N 1-methyladenosine (m1A), and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) (3). With the identification of different methyltransferase and demethylase enzymes, the physiological and pathological functions of RNA methylation have been gradually revealed, and have become an attractive area of research (4, 5).

The methylation of RNA represents one of the most ubiquitous modifications in mammalian cells and modulates multiple biological functions, especially innate and adaptive immune responses (6, 7). As crucial components of adaptive immunity, T cells are ready to prompt response to the foreign stimuli and mediate antiviral and antitumor immune responses (8, 9). Considering the importance of T cells’ immunological surveillance in the body and dynamic RNA methylation usually occurs in a very short time to initiate the regulatory role toward the target genes, it will be interesting to utilize T cell as an ideal model to understand how RNA epigenetic modifications quickly affect immune responses.

In this review, we will outline recent findings regarding the role of RNA methylation in regulating T cell function, highlight current challenges in these areas, and clarify the potential application of RNA methylation in orchestrating T cell immune responses.

RNA Methylation in T Cells

Methylation of RNA is indispensable for the biogenesis and function of prokaryotes and eukaryotes (10). This modification is widely distributed in messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), noncoding small RNA (sncRNA), and long-chain non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and can affect protein synthesis by regulating splicing, nuclear export, translation, and decay of RNA (10–13). With the discovery of m6A and identification of its critical role in regulating immune responses, emerging evidence has stimulated researchers to explore how other major forms of RNA methylation may modulate the host immune system, especially T cell immunity, to expand the basic understanding of the epitranscriptomic code of RNA.

N 6-methyladenosine (m6A)

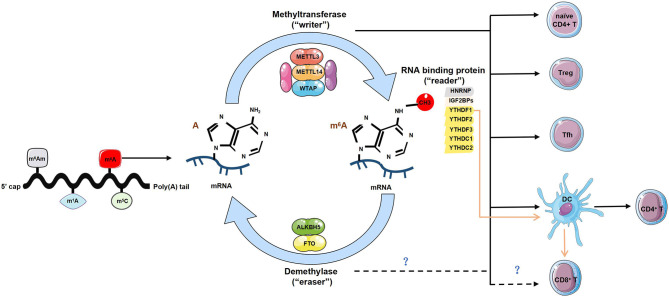

m6A refers to methylation of adenosine (A) at the nitrogen-6 position and represents one of the most frequent RNA modifications. It is preferentially enriched in 3’untranslated regions (3’UTR), long internal exons, and near stop codons of linear RNAs (14–16). The m6A modification is dynamically reversibly installed and removed by methyltransferases (“writers”) and demethylases (“erasers”) (17). The “writer” complex contains three core proteins: methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) (18, 19), METTL14 (20, 21), and Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP) (22, 23). Other newly recognized regulators including vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA, also called KIAA1429), RNA binding motif protein 15/15B (RBM15/15B), cbl-proto-oncogene-like protein 1 (CBLL1, also known as HAKAI), and Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13), are essential for the nuclear localization and stabilization of the “writer” complex, or m6A deposition specificity (6). The two currently identified ‘‘erasers’’ are fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) (24) and alkylated DNA repair protein AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) (25). FTO not only functions as the demethylase for m6A in mRNA, but also displays demethylase activity for m6Am and m1A for specific tRNA, snRNA, or mRNA (26). Multiple proteins that bind to m6A, affect the fate of the corresponding RNA and its downstream functions and are referred to as m6A-binding proteins (‘‘readers’’). To date, three different groups of “readers” have been identified: YTH-RNA binding domain family, including three YTH-domain-family (YTHDF1-3) and two YTH domain-containing (YTHDC1-2) proteins (27–29), the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP) family (30–32) and insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-biding proteins (IGF2BPs) (33, 34). All “readers” mediate regulatory functions of m6A on modified RNA and participate in RNA splicing nuclear export and storage, translation, and decay (27–29) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Writers, readers and erasers in predominant RNA methylations.

| RNA Modification | Writers | Erasers | Readers |

|---|---|---|---|

| m6A | METTL3; METTL14; WTAP; VIRMA; RBM15/15B; CBLL1; ZC3H13 | FTO; ALKBH5 | YTH-RNA binding domain family (YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2); heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (HNRNP) family; insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-biding proteins (IGF2BPs) |

| m6Am | PCIF1 | FTO | Not defined |

| m1A | TRMT6/TRMT61A; TRMT61B; TRMT10C; NML | FTO; ALKBH1; ALKBH3 | YTHDF1-3; YTHDC1 |

| m5C | NSUN1-7; DNMT2 | Not defined | ALYREF; YBX1 |

T cells, generally comprising CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells, largely represent the foundation of the adaptive immune system. Naïve CD4+ T cells exhibit features of stem cells, and will further differentiate into different T helper (Th) cell subsets upon stimulation by various microenvironmental signals (35, 36). Evidence from embryonic stem cells has indicated the importance of m6A in determining stem cell fates (37), implying the potential of m6A in directing Th cell differentiation. In 2017, our lab constructed a conditional knockout mouse model (Mettl3 flox/flox Cd4 Cre) for m6A writer protein-METTL3 in T cells, in the first attempt to elucidate the in vivo role of METTL3 and consequently the m6A RNA modification in regulating mouse T cells homeostasis and differentiation (38). Characterization of immune cell populations at steady state of this mice model revealed that the ablation of METTL3 in T cells disrupted T cell homeostasis (38). Furthermore, METTL3-deficient naïve CD4+ T cells differentiated into fewer Th1 and Th17 cells, more Th2 cells, without affecting regulatory T cells (Tregs) induction compared with WT naïve CD4+ T cells (38). Interestingly, METTL3 or METTL14 also promoted naïve CD4+ T cell homeostatic expansion in vivo during the adoptive transfer colitis model (38). With these observations, we determined that the mRNAs of the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family genes modified by m6A underwent rapid mRNA degradation upon interleukin (IL)-7 stimulation, thus initiating the homeostasis and differentiation of naïve T cells by relieving the block on the IL-7-signal transducers and activators of transcription 5 (STAT5) pathway (38). Shortly after, our omics data was re-evaluated by others, who comprehensively quantified the RNA dynamics of T cell during differentiation, and showed that m6A depletion impairs this process (39), further illustrating the importance of the epitranscriptomic m6A modification, in governing T cell homeostasis and function.

Although in vitro evidence suggests the dispensable role of METTL3 in directing Tregs differentiation by a T cell receptor (TCR)-dependent T cell induction system (38), whether m6A modification affects Tregs functions in vivo is still unclear. After observing that Mettl3 flox/flox Cd4 Cre mice developed spontaneous chronic inflammation in the intestine after 3 months of age, we hypothesized that Tregs might have impaired repressive functions in these mice (40). Therefore, we bred Mettl3 flox/flox Foxp3 Cre mice to specifically delete METTL3 expression in Tregs, and observed the development of severe systemic autoimmune diseases of the mice soon after weaning. The mice began to die at the ages of 8-9 weeks old, which was attributed to the systematic loss of Tregs suppressive function lacking m6A modification (40). Mechanistically, the METTL3-mediated m6A RNA modification specifically targets the SOCS gene family and sustains the suppressive functions of Tregs via the IL2-STAT5 pathway (40). The findings further implied that T cell-specific delivery of m6A-modifying agents might be employed in treating autoimmune disorders.

T follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, as a specialized CD4+ T cell subset, initiate germinal center (GC) formation and promote humoral immunity (41), whether their lineage differentiation can be directed by m6A modification remains to be identified. One study indicated that the knockdown of METTL3 or METTL14 in CD4+ T cells with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) could promote Tfh development upon lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection (42). However, other studies reported an opposite phenotype and pointed out that conditional ablation of METTL3 in CD4+ T cells dampened Tfh differentiation, proliferation, and survival ability after LCMV challenge (43). Notably, the latter study indicated that METTL3-mediated m6A modification of transcription factor 7 (TCF7) mRNA can stabilize the transcript, and therefore maintain protein expression of TCF7 to initiate and secure the differentiation of Tfh cells (43). This regulatory mechanism differs with naïve CD4+ T cells or Tregs, where METTL3-directed m6A modification decreases mRNA stabilization (38, 40). The divergent functional outcome of m6A modification mainly depends on diverse m6A “readers” in a cell type and cellular context-dependent fashion. Therefore, a deeper evaluation of the phenotypic effects of different m6A-readers will advance our knowledge of the m6A machinery.

m6A methylation may modulate T cells either directly or indirectly by affecting the function of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (44, 45). In YTHDF1-deficient mice, the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell antitumor response increased compared with wild-type mice, relying on enhanced cross-presentation of tumor antigens and cross-priming of CD8+ T cells by classical dendritic cells (cDCs) (44). Furthermore, METTL3-specific deficiency in DCs led to phenotypic and functional maturation defects, causing a reduction in levels of co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and cytokine IL-12, and reduced the ability to stimulate CD4+ T cell responses (45). These findings raise the possibility of exploiting m6A methylation to promote DC activation and DC-based T cell responses. However, whether the m6A machinery directly regulates the development and function of CD8+ T cells has yet to be determined.

Although current studies have highlighted the importance of m6A in governing T cell functions, it seems that these have only focused on better defining the role of the “writers” or “readers” ( Figure 1 ). It will be intriguing to characterize whether and how “erasers” control T cell homeostasis or functionality. It has been reported that dopamine receptors expressed in T cells are critical for instructing thymic T cell development and maintaining T cell function (46, 47). Interestingly, FTO can also participate in the dopamine signaling pathway (48); thus, it remains a possibility that FTO may affect T cell homeostasis or function via dopamine receptors. Recent studies have excluded the potential role of ALKBH5 in directing Tfh differentiation upon LCMV infection using shRNA-mediated knockdown of ALKBH5 (42). However, based on results obtained from macrophages, it has been suggested that ALKBH5 demethylates α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) transcript, increases its mRNA stability and protein expression, and metabolically promotes viral replication in macrophage (49), which still raises the possibility of ALKBH5 in maintaining T cell function and warrants additional investigation.

Figure 1.

The regulatory role of m6A modification in T cells. Diverse forms of RNA methylation have been identified on mRNAs, mainly involving N 6-methyladenosine (m6A), N 6-2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), N 1-methyladenosine (m1A) and 5-methylcytosine (m5C). m6A modification is reversibly installed and removed by methyltransferases (“writers”) and demethylases (“erasers”). Multiple proteins that bind to m6A to affect the fate of RNA are referred to as m6A-binding proteins (‘‘readers’’). The “writers” complex is mainly composed of METTL13, METTL14 and WTAP, can directly modulate T cells by maintaining homeostasis of naïve CD4+ T cells, promoting the function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T follicular helper (Tfh) cells. It also indirectly enhances CD4+ T cells function via promoting dendritic cell (DCs) activation and DC-based T cell response. The “readers” involve YTHDF1-3, YTHDC1-2, HNRNP and IGF2BPs. The lack of YTHDF1 can enhance antigen-specific CD8+ T cell antitumor response indirectly by the increased cross-priming of CD8+ T cells by DCs. However, whether the “writers” and “readers” directly regulates the development and function of CD8+ T cells is unknown. The current identified two ‘‘erasers’’ are FTO and ALKBH5, whether and how “erasers” control T cell homeostasis or functionality is yet to be determined.

N 6-2’-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am)

m6Am refers to the terminal modification of the first nucleotide after the mRNA 5’cap, and was first identified in animal cells and viral mRNA in 1975 (50). Usually, if this first nucleotide is 2-O-methyladenosine (Am), it can be further methylated at the nitrogen-6 position to form m6Am (50). Like m6A, m6Am is also dynamically regulated by methyltransferase and demethylase (51, 52). Phosphorylated CTD interacting factor 1 (PCIF1) is the only evolutionarily conserved methyltransferase for m6Am, and depleting PCIF1 leads to the deficiency of m6Am alone without affecting m6A levels or distribution (52–54). The function of PCIF1 is still controversial as one study indicated the loss of PCIF1 did not affect mRNA translation but reduced stability of a subset of m6Am-annotated mRNAs (52), while another reported that PCIF1 suppressed protein translation without influencing mRNA stability (55). The inconsistency may result from the different experimental systems used to dissect the effects of m6Am on translation, thus, it remains to be determined whether this effect is maintained, diminished, or enhanced under various biological circumstances.

Contrary to the specificity of ALKBH5 toward m6A modification, FTO shows wide reversible demethylation activity, and functions as a demethylase for the m6Am modification to reduce the stability of target mRNAs, preferentially demethylating m6Am rather than m6A (26, 56) ( Table 1 ). Considering the possible role of FTO in maintaining T cell development or function (48), additional studies are needed to characterize m6Am’s function in orchestrating T cell immunity.

N 1-methyladenosine (m1A)

The methylation on the nitrogen-1 position of adenosine to form m1A was first identified in tRNA (57). This modification is typically found at position 58 in the T-loop of tRNA (m1A58) (58, 59). The m1A modification on tRNA is of great importance for tRNA folding, stability, and tRNA-protein interaction (60–62). m1A has also been detected in rRNA and affects the tertiary structure of ribosomes and the translation of downstream genes (63, 64). Subsequently, the rare presence of m1A sites in mRNA and lncRNA was also reported (65, 66). Recent findings suggest that m1A at the coding sequence (CDS) in mitochondrial messenger RNA (mt-mRNA) blocks the effective translation of modified codons (66, 67). Moreover, ribosome profiling data indicate that m1A in nuclear mRNA might promote translation (67). However, the exact function of m1A in these RNAs still need further investigation.

m1A, as a reversible RNA modification, is catalyzed by methyltransferases including tRNA methyltransferase 6/61A (TRMT6/61A), TRMT61B, TRMT10C, and Nucleomethylin (NML), and by demethylases FTO, ALKBH1, and ALKBH3 (26, 58, 59, 67–70). YTHDF1-3 and YTHDC1 have been reported as the “readers” of m1A (71) ( Table 1 ). TRMT6/61A is responsible for the modification of a series of m1A sites in tRNA and lncRNA, recognizing the substrate RNA mainly through a strong T-loop structure typically comprising a 5-base pair (bp) stem and a 7-bp loop (67, 72). TRMT61B, as a mitochondrial-specific tRNA methyltransferase, has been reported to catalyze m1A modification in both tRNA and rRNAs (73, 74). TRMT10C can catalyze m1A modification in mitochondrial coding transcripts (75, 76), and NML will catalyze the formation of m1A at multiple rRNA sites both in human and mouse cells (77). Although distinct tRNA expression patterns and dynamic changes involving tRNA modification occur in early mouse CD4+ T cells activation, the m1A modification at position 58 of tRNA remains constant throughout this process (78), questioning whether m1A may regulate T cell activation. Therefore, uncovering the biological consequences of m1A under various physiological and pathological conditions in T cells will be critical to improve our understanding of the role that m1A machinery plays in regulating T cell immunity.

5-Methylcytosine (m5C)

The existence of m5C in RNAs has been known since the 1970s (79, 80). High throughput detection methods identified m5C as an abundant RNA modification in diverse RNA species, including mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and other ncRNAs (81). Like m6A, the m5C modification in RNA is also catalyzed by “writers”, including DNA methyltransferase homologs and members of the NOL1/NOP2/SUN domain (NSUN) family proteins (including NSUN1-7) and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) homologue DNMT2 (81–84), and “readers” like Aly/REF export factor (ALYREF) (85) and Y-box binding protein 1(YBX1) (86). However, the “erasers” of m5C in RNAs have not yet been identified ( Table 1 ). m5C has emerged as a critical regulator involved in modulating the export and stability of RNA, ribosome assembly, and translation (81, 87). However, the specific gene signatures of m5C-related regulators in T cell immunity remain largely unknown.

A recent study has reported reduced mRNA m5C levels in CD4+ T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) compared with CD4+ T cells of healthy controls (HCs) (88). NSUN2 is the only known mRNA m5C methyltransferase (75) and whose mRNA and protein expression is reduced dramatically in CD4+ T cells from SLE patients relative to HCs (88). Importantly, m5C hypomethylated transcripts in SLE stable groups or SLE moderate/major active groups have shown obvious enrichment of eukaryotic translation elongation and protein methylation (88). In addition, up-regulated genes presenting an abundance of m5C has been described to be involved in the flares and remission of SLE patients, and subsequent damage to the patient’s immune system (88). This study suggested the relevance of aberrant m5C mRNA modification in vital immune pathways of CD4+ T cells from SLE patients, but how the “writer” NSUN2 contributes to the m5C epitranscriptomic code during SLE is still unclear. Further studies are needed to acquire a better understanding of the role of NSUN2 in patients with SLE. Notably, other RNA methylations, such as 3-methylcytidine (m3C), N 1-methylguanosine (m1G), 5-methyluridine (m5U) have also been mapped in CD4+ T cells (88), and it would be interesting to explore whether these modifications exert a similar regulatory role with m6A in maintaining T cell homeostasis in the future.

Concluding Remarks

As a critical component of epigenetics, posttranscriptional RNA methylation provides abundant possibilities for different physiological and pathological processes relevant to T cells. Based on the complex self-regulatory processes in T cells, major knowledge gaps remain to be filled in this developing field. Studies in mice have deciphered the significance of m6A methylation as a “brake” to modulate transcription during T cell activation (38). Although many m6A sites have been detected on T cells, whether these sites are subject to an equal contribution from the action of “writers” and “erasers” needs to be further determined. Further, considering the importance of ‘‘writers’’ in maintaining T cell function, the role of m6A ‘‘erasers’’ in governing T cell homeostasis and function remains to be elucidated. Future studies are required to answer whether a selectivity and asymmetry in the actions of m6A “writers” and “erasers” is active in controlling T cell function.

Since our observations regarding the cross-talk between RNA modifications in colorectal cancer highlighted their therapeutic liability toward immunotherapy (89), it would be interesting to decipher the existence of a similar complex regulatory network in T cells, and to determine whether other RNA methylations might function as a sort of “gas pedal” or “pace keeper” to control T cell clonal expansion, differentiation, and subsequent effector functions. The identification of a specific RNA epigenetic translational checkpoint will advance our knowledge concerning how different RNA methylations are sequentially coordinated to regulate T cell immunity. Moreover, a proper investigation with the objective to explain why and under which conditions T cells rely on different types of RNA methylations to regulate gene expression will be a major step forward. Future explorations will reveal novel therapeutic targets by exploiting RNA methylations to alleviate T cell-related inflammatory diseases, infections, and to promote cancer immunotherapy.

Author Contributions

YC drafted the manuscript. HBL and JZ designed the review, wrote, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91753141/82030042/32070917 to HBL, 81901569 to JZ), Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (20JC1417400/201409005500/20JC1410100 to HBL), the Postdoctoral Innovation Talent Support Program (BX20190214 to JZ), the Shanghai Super Postdoctoral Program (JZ), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M671149 to JZ), the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning (HBL), the start-up fund from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (HBL).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Nachtergaele S, He C. Chemical modifications in the life of an mRNA transcript. Annu Rev Genet (2018) 52:349–72. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helm M, Motorin Y. Detecting RNA modifications in the epitranscriptome: predict and validate. Nat Rev Genet (2017) 18:275–91. 10.1038/nrg.2016.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, Piątkowski P, Bagiński B, Wirecki TK, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res (2018) 46:D303–7. 10.1093/nar/gkx1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi H, Wei J, He C. Where, when, and how: context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol Cell (2019) 74:640–50. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Motorin Y, Helm M. RNA nucleotide methylation. Wiley Interdiscip Reviews: RNA (2011) 2:611–31. 10.1002/wrna.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shulman Z, Stern-Ginossar N. The RNA modification N 6-methyladenosine as a novel regulator of the immune system. Nat Immunol (2020) 21:501–12. 10.1038/s41590-020-0650-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang C, Fu J, Zhou Y. A review in research progress concerning m6A methylation and immunoregulation. Front Immunol (2019) 10:922. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gleeson M, Bishop NC. The T cell and NK cell immune response. Ann Transplant (2005) 10:44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dermime S, Gilham DE, Shaw DM, Davidson EJ, Meziane E-K, Armstrong A, et al. Vaccine and antibody-directed T cell tumour immunotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Reviews Cancer (2004) 1704:11–35. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell (2017) 169:1187–200. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sergiev PV, Aleksashin NA, Chugunova AA, Polikanov YS, Dontsova OA. Structural and evolutionary insights into ribosomal RNA methylation. Nat Chem Biol (2018) 14:226. 10.1038/nchembio.2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romano G, Veneziano D, Nigita G, Nana-Sinkam SP. RNA methylation in ncRNA: classes, detection, and molecular associations. Front Genet (2018) 9:243. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, He C. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science (2018) 361:1346–9. 10.1126/science.aau1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U States A (1974) 71:3971–5. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perry RP, Kelley DE. Existence of methylated messenger RNA in mouse L cells. Cell (1974) 1:37–42. 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90153-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell (1975) 4:379–86. 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tong J, Flavell RA, Li H-B. RNA m 6 A modification and its function in diseases. Front Med (2018) 12:481–9. 10.1007/s11684-018-0654-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA (1997) 3:1233–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hongay CF, Orr-Weaver TL. Drosophila inducer of MEiosis 4 (IME4) is required for Notch signaling during oogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U States A (2011) 108:14855–60. 10.1073/pnas.1111577108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol (2014) 10:93–5. 10.1038/nchembio.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6 -methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol (2014) 16:191–8. 10.1038/ncb2902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res (2014) 24:177–89. 10.1038/cr.2014.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhong S, Li H, Bodi Z, Button J, Vespa L, Herzog M, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell (2008) 20:1278–88. 10.1105/tpc.108.058883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol (2011) 7:885–7. 10.1038/nchembio.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol Cell (2013) 49:18–29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, Fei Q, Ai Y, He PC, et al. Differential m6A, m6Am, and m1A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol Cell (2018) 71:973–85. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature (2012) 485:201–6. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu T, Roundtree IA, Wang P, Wang X, Wang L, Sun C, et al. Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res (2014) 24:1493–6. 10.1038/cr.2014.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell (2015) 161:1388–99. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m6A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell (2015) 162:1299–308. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N6 -methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature (2015) 518:560–4. 10.1038/nature14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu N, Zhou KI, Parisien M, Dai Q, Diatchenko L, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45:6051–63. 10.1093/nar/gkx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Recognition of RNA N 6 -methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20:285–95. 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou KI, Pan T. An additional class of m 6 A readers. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20:230–2. 10.1038/s41556-018-0046-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9:91–105. 10.1038/nri2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davenport MP, Smith NL, Rudd BD. Building a T cell compartment: how immune cell development shapes function. Nat Rev Immunol (2020) 20:499–506. 10.1038/s41577-020-0332-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, Qu K, Zhang J, Li L, et al. m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell (2014) 15:707–19. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li H-B, Tong J, Zhu S, Batista PJ, Duffy EE, Zhao J, et al. m 6 A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature (2017) 548:338–42. 10.1038/nature23450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Furlan M, Galeota E, De Pretis S, Caselle M, Pelizzola M. m6A-dependent RNA dynamics in T cell differentiation. Genes (2019) 10:28. 10.3390/genes10010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tong J, Cao G, Zhang T, Sefik E, Vesely MCA, Broughton JP, et al. m 6 A mRNA methylation sustains Treg suppressive functions. Cell Res (2018) 28:253–6. 10.1038/cr.2018.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (Tfh). Annu Rev Immunol (2011) 29:621–63. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu Y, Zhao Y, Zou L, Zhang D, Aki D, Liu Y-C. The E3 ligase VHL promotes follicular helper T cell differentiation via glycolytic-epigenetic control. J Exp Med (2019) 216:1664–81. 10.1084/jem.20190337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yao Y, Yang Y, Guo W, Xu L, You M, Zhang Y-C, et al. METTL3-dependent m 6 A modification programs T follicular helper cell differentiation. Nat Commun (2021) 12:1–16. 10.1038/s41467-021-21594-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han D, Liu J, Chen C, Dong L, Liu Y, Chang R, et al. Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m 6 A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature (2019) 566:270–4. 10.1038/s41586-019-0916-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang H, Hu X, Huang M, Liu J, Gu Y, Ma L, et al. Mettl3-mediated mRNA m(6)A methylation promotes dendritic cell activation. Nat Commun (2019) 10:1898. 10.1038/s41467-019-09903-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mignini F, Sabbatini M, Capacchietti M, Amantini C, Bianchi E, Artico M, et al. T-cell subpopulations express a different pattern of dopaminergic markers in intra-and extra-thymic compartments. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents (2013) 27:463–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang Y, Qiu A-W, Peng Y-P, Liu Y, Huang H-W, Qiu Y-H. Roles of dopamine receptor subtypes in mediating modulation of T lymphocyte function. Neuroendocrinol Lett (2010) 31:782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hess ME, Hess S, Meyer KD, Verhagen LA, Koch L, Brönneke HS, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat Neurosci (2013) 16:1042–8. 10.1038/nn.3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu Y, You Y, Lu Z, Yang J, Li P, Liu L, et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification–mediated cellular metabolism rewiring inhibits viral replication. Science (2019) 365:1171–6. 10.1126/science.aax4468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wei C-M, Gershowitz A, Moss BN. 6, O 2′-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5′ terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature (1975) 257:251–3. 10.1038/257251a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoie A, Jiao X, Grozhik AV, Patil DP, et al. Reversible methylation of m 6 A m in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature (2017) 541:371–5. 10.1038/nature21022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boulias K, Toczydłowska-Socha D, Hawley BR, Liberman N, Takashima K, Zaccara S, et al. Identification of the m6Am methyltransferase PCIF1 reveals the location and functions of m6Am in the transcriptome. Mol Cell (2019) 75:631–43. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun H, Zhang M, Li K, Bai D, Yi C. Cap-specific, terminal N 6-methylation by a mammalian m 6 Am methyltransferase. Cell Res (2019) 29:80–2. 10.1038/s41422-018-0117-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li K, Cai J, Zhang M, Zhang X, Xiong X, Meng H, et al. Landscape and regulation of m6A and m6Am methylome across human and mouse tissues. Mol Cell (2020) 77:426–440. e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sendinc E, Valle-Garcia D, Dhall A, Chen H, Henriques T, Sheng W, et al. PCIF1 catalyzes m6Am mRNA methylation to regulate gene expression. Mol Cell (2019) 75:620–30. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun B-F, Shi Y, Yang X, Xiao W, et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res (2014) 24:1403–19. 10.1038/cr.2014.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. RajBhandary UL, Stuart A, Faulkner RD, Chang SH, Khorana HG. Nucleotide sequence studies on yeast phenylalanine sRNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol (1966) 31:425–34. 10.1101/SQB.1966.031.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals reversible and dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome. Nat Chem Biol (2016) 12:311–6. 10.1038/nchembio.2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, et al. The dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature (2016) 530:441–6. 10.1038/nature16998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Degut C, Ponchon L, Folly-Klan M, Barraud P, Tisne C. The m1A(58) modification in eubacterial tRNA: An overview of tRNA recognition and mechanism of catalysis by TrmI. Biophys Chem (2016) 210:27–34. 10.1016/j.bpc.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oerum S, Dégut C, Barraud P, Tisné C. m1A post-transcriptional modification in tRNAs. Biomolecules (2017) 7:20. 10.3390/biom7010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. El Yacoubi B, Bailly M, De Crécy-Lagard V. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs, in. Annu Rev Genet (2012) p:69–95. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peifer C, Sharma S, Watzinger P, Lamberth S, Kotter P, Entian KD. Yeast Rrp8p, a novel methyltransferase responsible for m1A 645 base modification of 25S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res (2013) 41:1151–63. 10.1093/nar/gks1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sharma S, Watzinger P, Kötter P, Entian KD. Identification of a novel methyltransferase, Bmt2, responsible for the N-1-methyl-adenosine base modification of 25S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res (2013) 41:5428–43. 10.1093/nar/gkt195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Grozhik AV, Olarerin-George AO, Sindelar M, Li X, Gross SS, Jaffrey SR. Antibody cross-reactivity accounts for widespread appearance of m 1 A in 5’UTRs. Nat Commun (2019) 10:1–13. 10.1038/s41467-019-13146-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar-Yaacov D, et al. The m 1 A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature (2017) 551:251–5. 10.1038/nature24456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li X, Xiong X, Zhang M, Wang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, et al. Base-resolution mapping reveals distinct m1A methylome in nuclear-and mitochondrial-encoded transcripts. Mol Cell (2017) 68:993–1005. e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, Wang X, Fu Y, Wei J, et al. ALKBH1-Mediated tRNA Demethylation Regulates Translation. Cell (2016) 167:1897. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nachtergaele S, He C. Chemical Modifications in the Life of an mRNA Transcript. Annu Rev Genet (2018) 52:349–72. 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Peer E, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Rechavi G, Dominissini D. The Epitranscriptome in Translation Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2019) 11:a032623. 10.1101/cshperspect.a032623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dai X, Wang T, Gonzalez G, Wang Y. Identification of YTH Domain-containing proteins as the readers for N 1-Methyladenosine in RNA. Anal Chem (2018) 90:6380–4. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar-Yaacov D, et al. The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature (2017) 551:251–5. 10.1038/nature24456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bar-Yaacov D, Frumkin I, Yashiro Y, Chujo T, Ishigami Y, Chemla Y, et al. Mitochondrial 16S rRNA Is Methylated by tRNA Methyltransferase TRMT61B in All Vertebrates. PloS Biol (2016) 14:e1002557. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chujo T, Suzuki T. Trmt61B is a methyltransferase responsible for 1-methyladenosine at position 58 of human mitochondrial tRNAs. Rna (2012) 18:2269–76. 10.1261/rna.035600.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li Q, Li X, Tang H, Jiang B, Dou Y, Gorospe M, et al. NSUN2-mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation. J Cell Biochem (2017) 118:2587–98. 10.1002/jcb.25957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Metodiev MD, Thompson K, Alston CL, Morris AAM, He L, Assouline Z, et al. Recessive Mutations in TRMT10C Cause Defects in Mitochondrial RNA Processing and Multiple Respiratory Chain Deficiencies. Am J Hum Genet (2016) 98:993–1000. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Waku T, Nakajima Y, Yokoyama W, Nomura N, Kako K, Kobayashi A, et al. NML-mediated rRNA base methylation links ribosomal subunit formation to cell proliferation in a p53-dependent manner. J Cell Sci jcs (2016) 129:2382–93. 10.1242/jcs.183723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rak R, Polonsky M, Eizenberg I, Dahan O, Friedman N, Pilpel Y. Dynamic changes in tRNA modifications and abundance during T-cell activation. bioRxiv (2020). 10.1101/2020.03.14.991901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dubin DT, Taylor RH. The methylation state of poly A-containing messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res (1975) 2:1653–68. 10.1093/nar/2.10.1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Perry RP, Kelley DE, Friderici K, Rottman F. The methylated constituents of L cell messenger RNA: evidence for an unusual cluster at the 5’ terminus. Cell (1975) 4:387–94. 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90159-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Trixl L, Lusser A. The dynamic RNA modification 5-methylcytosine and its emerging role as an epitranscriptomic mark. Wiley Interdiscip Reviews: RNA (2019) 10:e1510. 10.1002/wrna.1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Reid R, Greene PJ, Santi DV. Exposition of a family of RNA m 5 C methyltransferases from searching genomic and proteomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res (1999) 27:3138–45. 10.1093/nar/27.15.3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Jeltsch A, Ehrenhofer-Murray A, Jurkowski TP, Lyko F, Reuter G, Ankri S, et al. Mechanism and biological role of Dnmt2 in nucleic acid methylation. RNA Biol (2017) 14:1108–23. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1191737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Goll MG, Kirpekar F, Maggert KA, Yoder JA, Hsieh C-L, Zhang X, et al. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA methyltransferase homolog Dnmt2. Science (2006) 311:395–8. 10.1126/science.1120976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yang X, Yang Y, Sun BF, Chen YS, Xu JW, Lai WY, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res (2017) 27:606–25. 10.1038/cr.2017.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chen X, Li A, Sun B-F, Yang Y, Han Y-N, Yuan X, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs. Nat Cell Biol (2019) 21:978–90. 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bohnsack KE, Höbartner C, Bohnsack MT. Eukaryotic 5-methylcytosine (m5C) RNA methyltransferases: mechanisms, cellular functions, and links to disease. Genes (2019) 10:102. 10.3390/genes10020102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Guo G, Wang H, Shi X, Ye L, Yan K, Chen Z, et al. Disease Activity-Associated Alteration of mRNA m5 C Methylation in CD4+ T Cells of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Cell Dev Biol (2020) 8:430. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chen H, Yao J, Bao R, Dong Y, Zhang T, Du Y, et al. Cross-talk of four types of RNA modification writers defines tumor microenvironment and pharmacogenomic landscape in colorectal cancer. Mol cancer (2021) 20:1–21. 10.1186/s12943-021-01322-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]