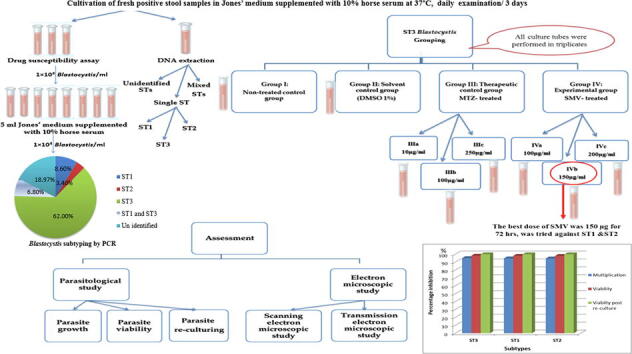

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Blastocystis subtypes, In vitro, Re-culture, Simeprevir, Ultrastructure, Viability

Abbreviations: IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ST, subtypes; MTZ, Metronidazole; SMV, Simeprevir; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; DMSO, Dimethyl Sulfoxide; SEM, Scanning electron microscopy; TEM, Transmission electron microscopy; CV, central vacuole; MLO, Mitochondrion-like organelle

Abstract

Introduction and aim

Blastocystis is a common enteric parasite, having a worldwide distribution. Many antimicrobial agents are effective against it, yet side effects and drug resistance have been reported. Thus, ongoing trials are being conducted for exploring anti-Blastocystis alternatives. Proteases are attractive anti-protozoal drug targets, having documented roles in Blastocystis. Serine proteases are present in both hepatitis C virus and Blastocystis. Since drug repositioning is quite trendy, the in vitro efficacy of simeprevir (SMV), an anti-hepatitis serine protease inhibitor, against Blastocystis was investigated in the current study.

Methods

Stool samples were collected from patients, Alexandria, Egypt. Concentrated stools were screened using direct smears, trichrome, and modified Ziehl-Neelsen stains to exclude parasitic co-infections. Positive stool isolates were cultivated, molecularly subtyped for assessing the efficacy of three SMV doses (100,150, and 200 μg/ml) along 72 hours (h), on the most common subtype, through monitoring parasite growth, viability, re-culture, and also via ultrastructure verification. The most efficient dose and duration were later tested on other subtypes.

Results

Results revealed that Blastocystis was detected in 54.17% of examined samples. Molecularly, ST3 predominated (62%), followed by ST1 (8.6%) and ST2 (3.4%). Ascending concentrations of SMV progressively inhibited growth, viability, and re-culture of treated Blastocystis, with a non-statistically significant difference when compared to the therapeutic control metronidazole (MTZ). The most efficient dose and duration against ST3 was 150 µg/ml for 72 h. This dose inhibited the growth of ST3, ST1, and ST2 with percentages of 95.19%, 94.83%, and 94.74%, successively and viability with percentages of 98.30%, 98.09%, and 97.96%, successively. This dose abolished Blastocystis upon re-culturing. Ultra-structurally, SMV induced rupture of Blastocystis cell membrane leading to necrotic death, versus the reported apoptotic death caused by MTZ. In conclusion, 150 µg/ml SMV for 72 h proved its efficacy against ST1, ST2, and ST3 Blastocystis, thus sparing the need for pre-treatment molecular subtyping in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Blastocystis has a worldwide distribution, with a higher prevalence in developing countries reaching up to 60% compared to the developed countries (Khoshnood et al., 2015). It is more common among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and immune-compromised patients (Mohamed et al., 2017). Genus Blastocystis is classified into more than 17 subtypes (STs) which may explain variations in symptoms and response to treatment (Coyle et al., 2012, Maloney et al., 2019, Stensvold and Clark, 2020). Subtypes related to infections in humans are one to nine, with subtype three being the most predominant human subtype in many countries (Abaza et al., 2014, Lepczynska et al., 2017).

Metronidazole (MTZ) is the drug of choice for Blastocystis treatment (Adao and Rivera, 2018). Most antimicrobial therapies against Blastocystis, including MTZ, have documented side effects that are not tolerated by many patients. Moreover, drug resistance has been reported (Coyle et al., 2012, Sekar and Shanthi, 2013). Previous studies have reported subtype-dependent variations in drug susceptibilities; one of them reported the resistance achieved by ST3 (Rajamanikam et al., 2019). Hence, many studies were designed to explore in vitro and in vivo therapeutic alternatives for Blastocystis management (El Deeb et al., 2012, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013, Roberts et al., 2015).

The preliminary step of drug discovery is to select an enzyme that is essential in the biological pathways of an organism (Das et al., 2013). Proteases are attractive key enzymes, because of their role in the survival, metabolism, replication, and pathogenesis of parasites (Mckerrow et al., 2008). There are different types of proteases; of which, Blastocystis-derived serine proteases play a major role in the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, protein kinase activation and also in the pathogenesis of IBS (Poirier et al., 2012, Lim et al., 2014). Since drug repositioning is quite trendy and serine proteases are present in both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and Blastocystis (Dunn et al., 2007; Alfonso and Monzote, 2011, Poirier et al., 2012, Izquierdo et al., 2014), the idea of trying serine protease inhibitor as a therapeutic alternative against Blastocystis has been encouraged.

Simeprevir (SMV) is a highly effective and safe anti-hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor, with tolerable adverse effects as it is less active against human proteases (Tanwar et al., 2012, Izquierdo et al., 2014). Hence, this study was designed to evaluate its in vitro efficacy against Blastocystis.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Stool samples collection, processing, and in vitro cultivation

The current study was conducted on 120 stool samples, which have been collected from patients with gastrointestinal symptoms from different departments and outpatient clinics of Alexandria University Hospitals and the Medical Research Institute, Alexandria, Egypt.

Each stool sample was screened for Blastocystis using saline and iodine smears, formol ether sedimentation concentration technique, and trichrome stain to exclude parasitic co-infections. Moreover, modified Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain was used to exclude co-infections by intestinal coccidia (Garcia, 2007).

After excluding co-infection with other parasites, positive stool isolates were individually cultivated in a set of four culture tubes; each containing five ml of Jones’ medium supplemented with 10% horse serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Culture tubes were incubated in an upright position at 37 °C and were daily monitored, for 72 hours (h) using iodine smear (El-Sayed et al., 2017).

By the end of the cultivation interval, culture sediment of each isolate was examined by iodine smear, then the four tubes were divided as follows; three tubes were further sub-cultured for conducting the drug susceptibility assay, while 0.5 ml of the fourth culture tube sediment was frozen at −20 °C for DNA extraction (Mokhtar et al., 2019).

2.2. DNA extraction and Blastocystis subtyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from thawed culture sediments with a DNA extraction kit, according to the manufacturer’s directions (QIAamp; Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany) (Mohamed et al., 2017). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out using three pairs of subtype-specific diagnostic primers as follows: STI (SB83) (F: GAAGGACTCTCTGACGATGA, R: GTCCAAATGAAAG GCAGC), ST2 (SB155) (F: ATCAGCCTACAATCTCCTC, R: ATCGCCACTTCTCCAAT) and ST3 (SB227) (F: TAGGATTTGGTGTTTGGAG A, R: TTAGAAGTGAAGGAGATGGAAG) (Khademvatan et al., 2018).

Extracted DNA was used as a template for the amplification in a 50 μl reaction mixture containing 25 μl Dream Taq PCR Master Mix (2×), 50 pmol of each primer set pair (one ST at a time) and 19 μl nuclease-free water. The PCR reactions were performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) which include denaturation for 30 s at 94 °C, annealing for 30 s at 58 °C, and extending for 1 min at 72 °C. Up to 35 cycles are required to amplify the DNA target, with an additional final extension cycle for 5 min at 72 °C (Abaza et al., 2014, Mohamed et al., 2017).

Amplification products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gel (Primega, USA) and Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and was photographed by an ultraviolet gel documentation system. For each isolate, each primer pair of PCR amplification was done twice (Abaza et al., 2014).

2.3. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing

2.3.1. Drugs

Metronidazole tablets (Flagyl®) (Sanofi Aventis Co.) were used as a therapeutic control. The drug was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). MTZ concentrations were adjusted to 10, 100, and 250 µg/ml (El Deeb et al., 2012, Roberts et al., 2015).

Simeprevir capsules (Olysio®) (Janssen) were tried against Blastocystis (Lin et al., 2009). The drug was dissolved in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent. Final concentrations of SMV were adjusted to a gradient concentration of 100, 150, and 200 µg/ml according to a preceding pilot study.

2.3.2. In vitro experimental design

Drug assay was primarily performed on the predominant molecularly verified subtype, then the most efficient dose and duration against this subtype were applied on the other tested subtypes. For each tested isolate, inocula of 1 × 104 Blastocystis /ml were further sub-cultured, at 37 °C for 72 h (Haresh et al., 1999). Subculture tubes were divided into four groups and were performed in triplicates. Group (I) was the non-treated infected control. Group (II) was the 1% DMSO solvent control. Group (III), the therapeutic control, was further subdivided into subgroups III (a, b & c); treated with MTZ at concentrations of 10, 100, and 250 μg/ml, successively. Group (IV), the experimental SMV-treated, was further subdivided into subgroups IV (a, b & c); treated with SMV at concentrations of 100, 150, and 200 μg/ml, successively.

2.3.3. Assessment of in vitro anti-Blastocystis activity of SMV

The activity of SMV has been evaluated after 24, 48, and 72 h, then was compared to the corresponding controls.

2.3.3.1. Parasite growth

Daily quantitation of Blastocystis was performed by a hemocytometer using iodine smears for three days (Yakoob et al., 2011).

2.3.3.2. Parasite viability

Viability of the retrieved Blastocystis was evaluated using eosin-brilliant cresyl blue dye. Where, viable Blastocystis completely or partially excluded the dye, while dead ones took it up (Haresh et al., 1999, El-Sayed et al., 2017).

Percentage inhibition of Blastocystis multiplication/viability in the experimental group (IV) and both the therapeutic control group (III) and solvent control group (II) in relation to the non-treated control group (I) was calculated according to the following formula:

Where “a” is the mean number/mean viable intact Blastocystis in the non-treated control group and “b” is the mean number/mean viable intact Blastocystis in the tested group (experimental, therapeutic control, or solvent control) (El-Sayed et al., 2017).

Growth and viability profiles of each subgroup were recorded along the three studied intervals.

2.3.3.3. Parasite re-culturing

One hundred µl of culture sediments obtained from all groups was further re-cultured in fresh culture media for 72 h. The viability of re-cultured Blastocystis was evaluated using eosin-brilliant cresyl blue dye as mentioned before (Eida et al., 2008, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013).

2.3.3.4. Electron microscopic study (EM)

The effect of SMV on Blastocystis ultrastructure was studied, using both; scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The study was performed on pooled subcultures treated with the most efficient dose and duration of SMV and was compared to the non-treated control group (I). Pooled subculture sediments were washed using phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 three times and centrifuged for 5 min at 2000xg. The resulting pellet was then fixed in buffered glutaraldehyde-phosphate 2.5% and processed for SEM and TEM studies (Zhang et al., 2012, Dhurga et al., 2016).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software package version 20.0 and described using mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison between different groups at different time intervals were done using One-way and Two-way ANOVA tests. Percentage inhibition by the used drugs at different durations were compared using the Chi-square test. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level (Kotz et al., 2006).

3. Results

3.1. Stool samples processing and in vitro cultivation

Screening of the 120 collected stool samples by light microscopic examination revealed that 65 samples were positive for Blastocystis (54.17%). Seven stool samples out of 65 positive samples (10.77%) showed concurrent parasitic infections being; Giardia lamblia in five samples (7.70%), Cryptosporidium oocysts in one sample (1.50%), and eggs of Hymenolepis nana in another sample (1.50%).

3.2. DNA extraction and Blastocystis subtyping

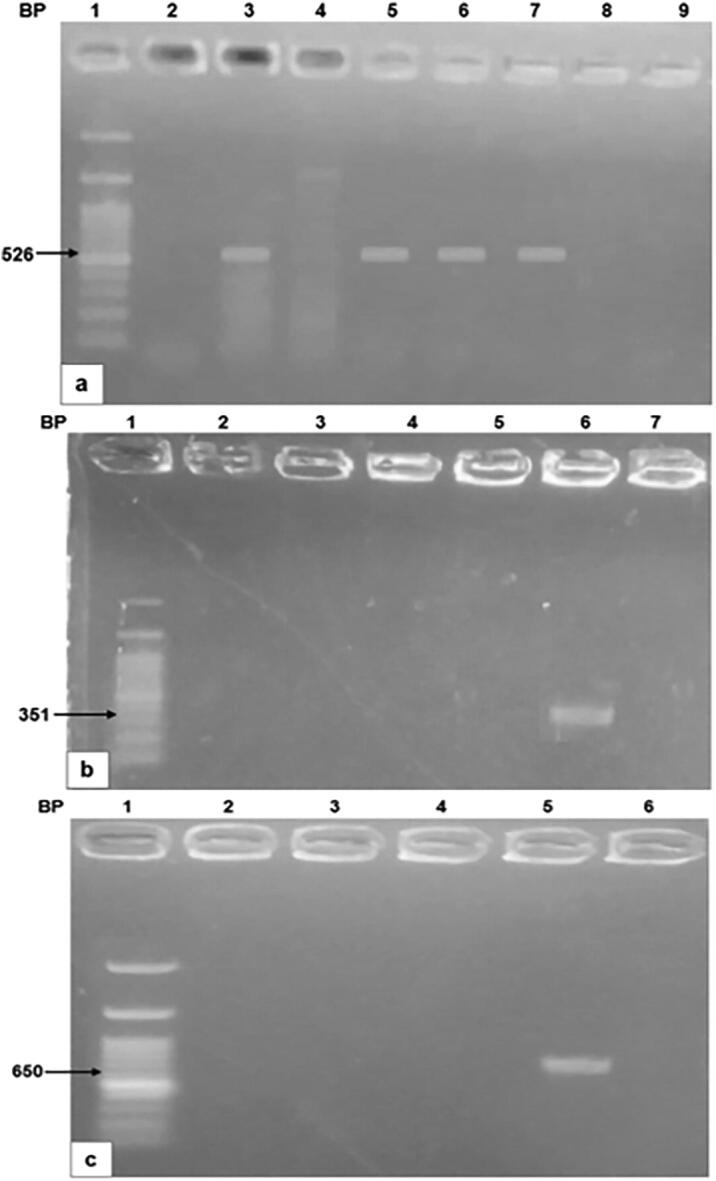

After excluding samples with mixed infection, all microscopically positive samples were culture positive. Out of the 58 positive stool cultures, 36 isolates (62.00%) were amplified with SB227 primer (526 bp), being identified as ST3 (Fig. 1a). Whereas five isolates (8.60%) were amplified with SB83 primer (351 bp), being identified as ST1 (Fig. 1b). Only two isolates (3.40%) were amplified with SB155 primer (650 bp), being identified as ST2 (Fig. 1c). Four isolates (6.80%) contained mixed infection with ST1 and ST3. Eleven isolates were not amplified with any of the used three primers (18.97%).

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel analysis of PCR-amplified products of Blastocystis.1a: Amplification with SB227 primer (526 bp) (ST3), 1b: Amplification with SB83 primer (351 bp) (ST1), 1c: Amplification with SB155 primer (650 bp) (ST2).

3.3. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing

After excluding isolates containing mixed molecular subtypes and subtypes that were not identified with any of the used three primers, drug assay has been performed on ST3 as it was the most commonly detected subtype. Then, the most efficient dose and duration against ST3 was applied on ST1 and ST2. Results of this dose and duration were compared among the three tested subtypes.

3.3.1. Parasitological study (parasite growth, viability, and re-culture):

3.3.1.1. Assessment of ST3 Blastocystisʹ response to SMV

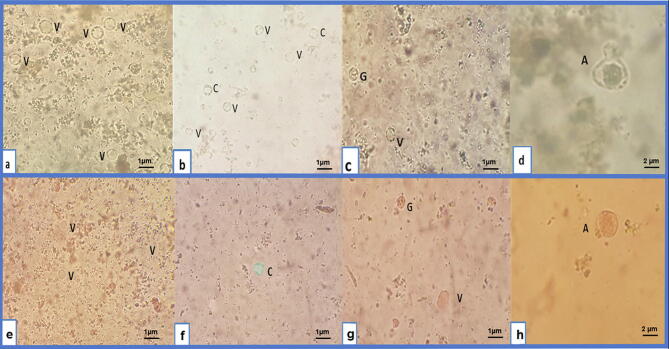

Vacuolar, granular and cystic forms were detected in groups (I), (II), and (III), whereas in the SMV-treated group (IV), granular form disappeared and amoeboid form was detected. Detected Blastocystis showed variations in their shape and size ranging from 1 to 3 µm (Fig. 2a, b, c& d). On using eosin-brilliant cresyl blue dye, viable Blastocystis completely or partially excluded the dye, appearing green, while dead ones absorbed it, appearing red in color (Fig. 2e, f, g & h).

Fig. 2.

Light microscopic findings of Blastocystis forms detected after drug testing by iodine smears and eosin-brilliant cresyl blue dye (×400). 2a: Vacuolar (V) form by iodine smear, 2b: Vacuolar (V) and cystic (C) forms by iodine smear, 2c: Vacuolar (V) and granular (G) forms by iodine smear, 2d: Amoeboid (A) form by iodine smear, 2e: Viable vacuolar (V) form, 2f: Viable cyst (C) form, 2g: Non-viable vacuolar (V) and granular (G) forms, 2h: Non-viable amoeboid (A) form.

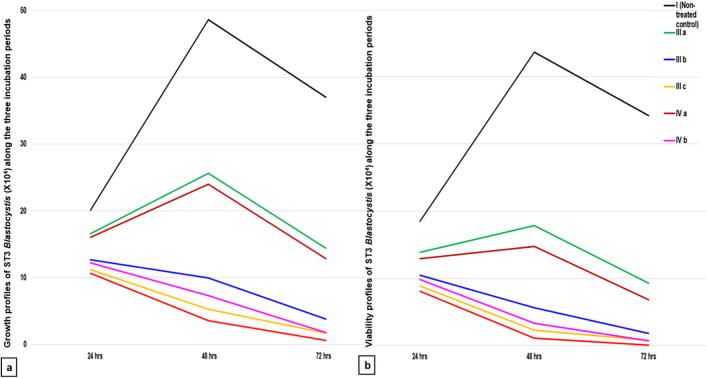

Growth and viability profiles of the non-treated control group (I) showed a statistically significant increase in the mean Blastocystis count and viability at 48 h compared to 24 h, followed by a statistically significant reduction at 72 h as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Growth and viability profiles of ST3 Blastocystis along the three-times intervals for the SMV tested doses versus their respective non-treated and MTZ-treated controls. a: Growth profile b: Viability profile. I (non-treated control), III (MTZ-treated control): IIIa (10 µg/ ml), IIIb(100 µg/ml), IIIc(250 µg/ml), IV (SMV-treated): IVa(100 µg/ml), IVb(150 µg/ ml), IVc(200 µg/ml).

In group (II), DMSO proved to have a non-statistically significant effect (p > 0.05) on Blastocystis growth and viability in comparison to the non-treated control group I, consequently, a comparison of all groups was made only to the non-treated control group (I).

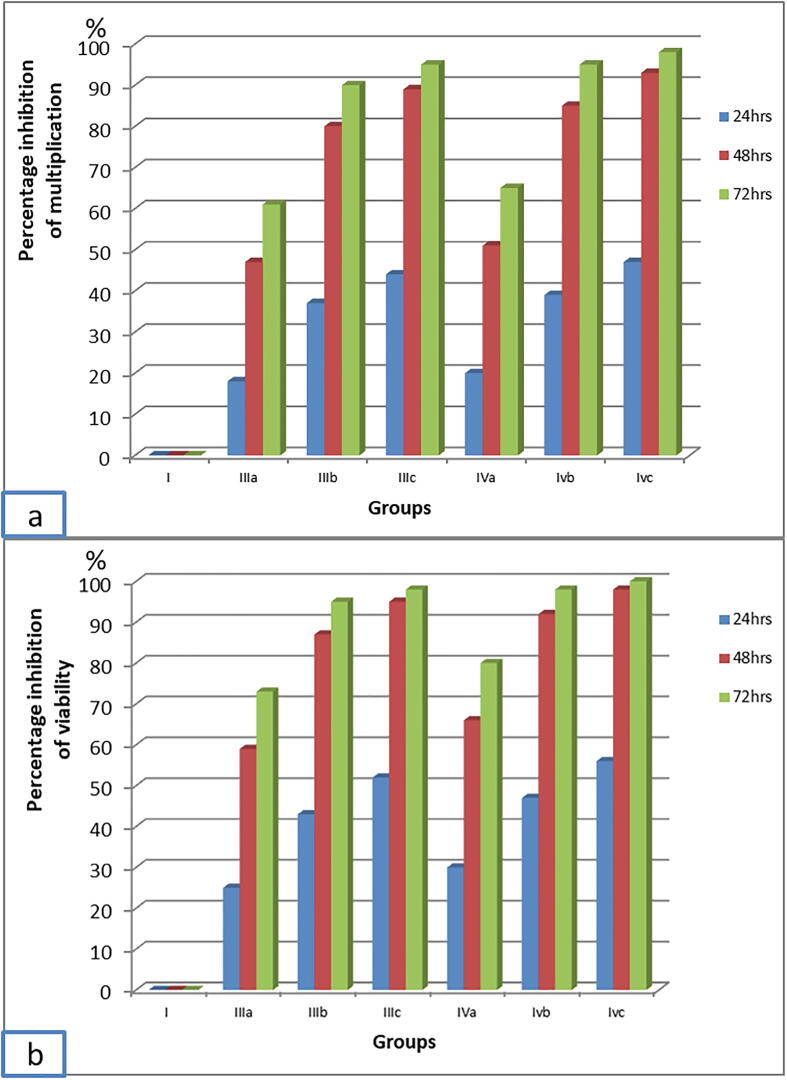

Regarding group III and group IV that were treated with MTZ and SMV respectively, there was a significant progressive decline in the mean count and viability of ST3 Blastocystis which was proportional to both; the increase in MTZ and SMV concentrations and the duration of exposure to the two drugs (Fig. 3). The highest inhibition of Blastocystis multiplication (98.35%) was recorded with 200 µg/ml SMV at 72 h. This inhibition was statistically significant when compared to the same dose at 48 h (92.64%). However, this inhibition was not statistically significant when compared to 150 µg/ml SMV at 72 h (95.19%) with (p = 0.256).

Blastocystis viability was affected in the same manner of growth (Fig. 3). 99.77% non-viable Blastocystis were recorded with 200 µg/ml SMV at 72 h. This dramatic inhibition of Blastocystis viability was statistically significant, when compared to the effect of the same dose at 48 h (97.57%). However, inhibition of Blastocystis viability was not statistically significant when compared to the dose of 150 µg/ml at 72 h (98.30%) with (p = 0.176) (Fig. 4), so the most efficient dose and duration was 150 µg/ml for 72 h. This dose showed non-statistically significant viability inhibition in comparison to the intermediate dose of MTZ at 72 h (94.65%) with (p = 0.242).

Fig. 4.

Percentage inhibition of ST3 Blastocystis multiplication and viability by MTZ and SMV versus its respective non-treated control group. 4a: Percentage inhibition of ST3 Blastocystis multiplication, 4b: Percentage inhibition of ST3 Blastocystis viability. I (non-treated control), II (Solvent control), III (MTZ-treated control): IIIa (10 µg/ ml), IIIb(100 µg/ml), IIIc(250 µg/ml), IV (SMV-treated): IVa(100 µg/ml), IVb(150 µg/ ml), IVc(200 µg/ml).

No viable Blastocystis was detected after re-culturing of ST3 Blastocystis previously exposed to the intermediate and high doses of SMV at 48 h and 72 h (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Re-culturing of ST3 Blastocystis previously inoculated with SMV at different incubation periods versus its respective non-treated and treated controls. I (non-treated control), II (Solvent control), III (MTZ-treated control): IIIa(10 µg/ml), IIIb(100 µg/ml), IIIc (250 µg/ml), IV (SMV-treated): IVa(100 µg/ml), IVb(150 µg/ml), IVc(200 µg/ml).

It was worth noting that two isolates molecularly belonging to ST3 didn’t show a significant response to any dose or duration of MTZ, but responded to the most efficient dose and duration of SMV (data not shown) which requires further extensive verification studies.

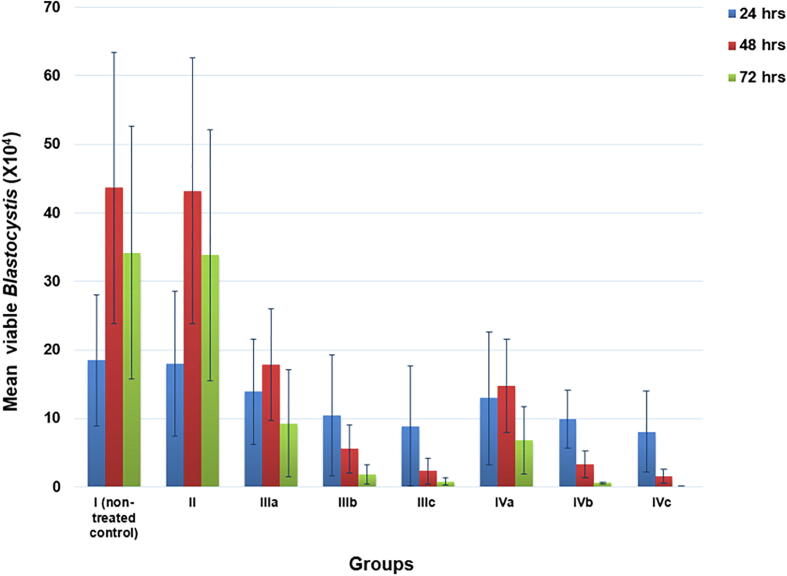

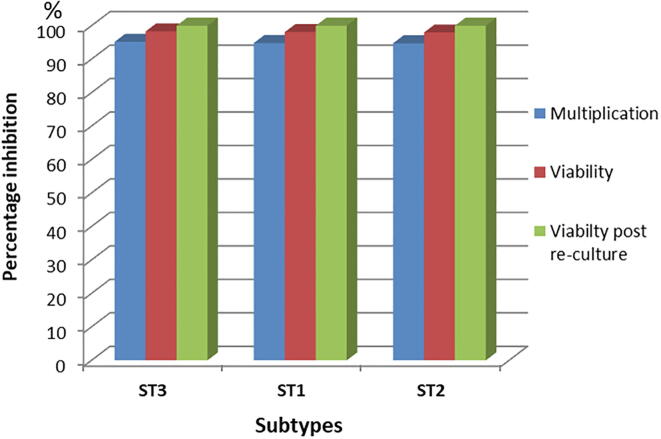

3.3.1.2. Assessment of ST1 and ST2 Blastocystis response to SMV

Fig. 6 revealed that there was no significant difference between the achieved inhibition in Blastocystis growth, viability, and re-culture in both ST1 and ST2 Blastocystis when compared to ST3 on applying the most efficient dose and duration of SMV (150 µg/ml for 72 h) on them.

Fig. 6.

Effect of 150 µg/ml SMV for 72 h on the percentage inhibition of multiplication, viability and viability post re-culture of ST1 and ST2 Blastocystis in comparison to ST3.

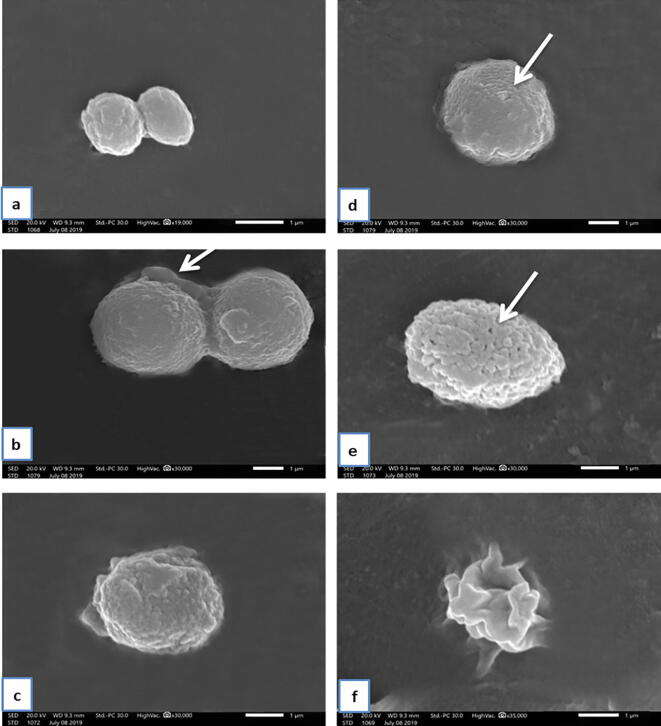

3.3.2. Electron microscopic study:

Using SEM, Blastocystis in the non-treated control group (I) was round or oval with a surface showing many indentations. Moreover, a fibrous surface coat attaching to cell surfaces of Blastocystis was shown in Fig. 7a and b. In SMV-treated group (IV), while the majority retained their spherical shape (Fig. 7c & d), some Blastocystis showed irregular amoeboid forms (Fig. 7f). Additionally, the surface of SMV-treated Blastocystis showed remarkable convolutions and folding (Fig. 7c), with occasional surface membrane pores in some of them (Fig. 7e).

Fig. 7.

(a-f): Scanning electron microscopy of the non-treated Blastocystis and SMV-treated groups. a: Non-treated Blastocystis showing its oval shape (X19000). b: Non-treated Blastocystis showing its round shape and fibrous surface coat attached to cell surfaces of Blastocystis (arrow) (×30000). c: SMV-treated Blastocystis showing remarkable convolution and folding (arrow) (×30000). d & e: SMV-treated Blastocystis showing remarkable convolution and folding and surface membrane pores (arrow) (×30000). f: SMV-treated Blastocystis amoeboid form (×35000).

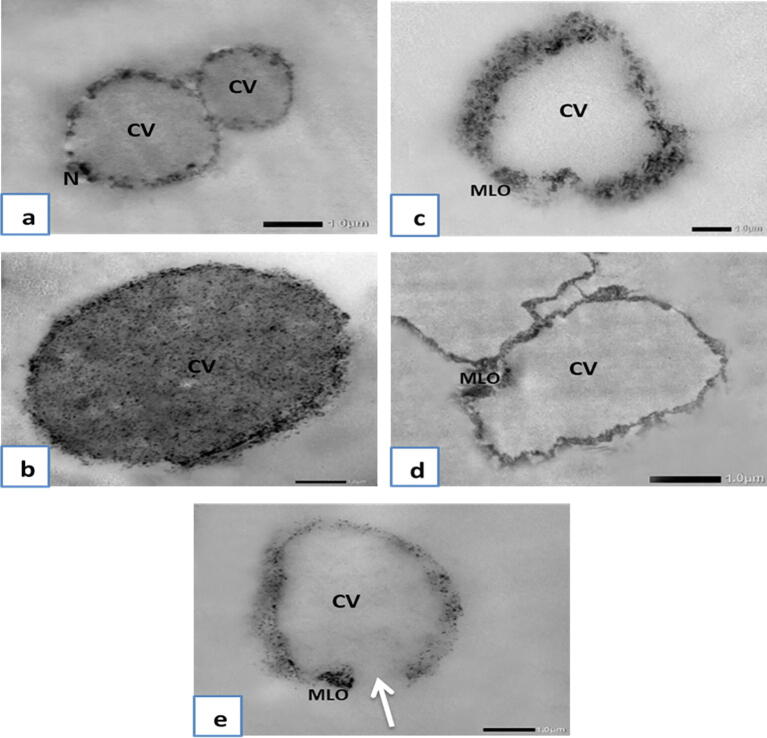

Using TEM, Blastocystis in the non-treated control group (I) showed that the vacuolar form was round or oval in shape with a central vacuole and thin rim of cytoplasm with a nucleus of a crescent band of electron opaque material at one pole (Fig. 8a). The granular form was round in shape and was similar in size to the vacuolar form. Yet, the central body was almost filled with granules of different electron densities and was surrounded by a peripheral rim of the cytoplasm (Fig. 8b). In the SMV-treated group (IV), Blastocystis was electron-lucent and the central vacuole seemed devoid of any electron-dense particles (Fig. 8c). Some showed plasma membrane rupture with subsequent loss of intracellular contents (Fig. 8e). SMV-treated Blastocystis amoeboid form with central vacuole (CV) and mitochondrion-like organelle (MLO) is shown in Fig. 8d.

Fig. 8.

(a-e): Transmission electron microscopy of non-treated Blastocystis and SMV-treated groups. a: Non-treated Blastocystis vacuolar form showing central vacuole (CV) and thin rim of cytoplasm with peripheral nuclei (N) (×6,000). b: Non-treated Blastocystis granular form showing central vacuole (CV) almost filled with granules of different electron densities and surrounded with peripheral rim of the cytoplasm (×8,000). c: SMV-treated Blastocystis vacuolar form showing central vacuole (CV) devoid of any electron-dense particles and showing mitochondrion-like organelle (MLO) (×6,000). d: SMV-treated Blastocystis amoeboid form showing central vacuole (CV) devoid of any electron-dense particles and showing mitochondrion-like organelle (MLO) (×6,000). e: SMV-treated Blastocystis showing central vacuole (CV) devoid of any electron-dense particles, and showing mitochondrion-like organelle (MLO) and plasma membrane rupture (arrow) (×6,000).

4. Discussion

Aiming at finding a promising anti-Blastocystis therapeutic alternative through drug repurposing, the current study explored the in vitro effect of SMV, an anti-HCV serine protease inhibitor, against Blastocystis. For fulfilling this aim, human stool samples were screened by light microscopy, positive samples were cultivated and molecularly subtyped for performing the drug assay on the identified subtypes.

Light microscopic screening revealed the presence of Blastocystis in 54.17% of the examined stool samples which have been collected from Alexandria, Egypt. Prevalence of 67.4% and 52% were previously reported in Alexandria in 2016 and 2019, respectively (Eassa et al., 2016, Elsayad et al., 2019), while in other Egyptian governorates prevalence ranged from 10% up to 53% (El-Shewy et al., 2002; El-Marhoumy et al., 2015, Farghaly et al., 2017). Epidemiological studies in several countries with different sanitation standards, revealed a wide range of Blastocystis prevalence ranging from 0.54% up to 63% (Beyhan et al., 2015, Duda et al., 2015, El Safadi et al., 2016, Osman et al., 2016, Ramírez et al., 2016, Seyer et al., 2017, Asfaram et al., 2019, Delshad et al., 2020, Zanetti et al., 2020)

Out of the 65 positive cases infected with Blastocystis in the current study, seven isolates were co-infected with Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium oocysts, and eggs of Hymenolepis nana (10.77%). Giardia lamblia was the most frequent concurrent parasite in the current work. This association was in accordance with that reported by Nascimento and Moitinho Mda, 2005, Elghareeb et al., 2015.

In the current study, molecular subtyping has been done using ST1, ST2, and ST3 primers, since they are the most commonly detected STs in Egypt (Souppart et al., 2010, Abaza et al., 2014). ST3 was the most predominant subtype in this study (62%). Other authors agreed with this result, where the predominance of ST3 in Egypt was reported also in Cairo (61.9%) (Souppart et al., 2010), (44.54%) (Fouad et al., 2011) and Suez Canal (56.1%) (Abaza et al., 2014). Moreover, different epidemiological studies around the world reported that a majority of human Blastocystis infections was attributable to ST3 isolates in different countries with percentages ranging from 31.2% to 53% (Meloni et al., 2011, Forsell et al., 2012, Moosavi et al., 2012, Roberts et al., 2013, El Safadi et al., 2016, Ramírez et al., 2016, Seyer et al., 2017, Jiménez et al., 2019). Nevertheless, fewer studies reported the predominance of ST1 and ST4 in other countries (Malheiros et al., 2011, Lee et al., 2012, Thathaisong et al., 2013, Delshad et al., 2020, Zanetti et al., 2020). Prevalence variations of Blastocystis subtypes between different countries, and also within the same country, might be attributed to variable epidemiological conditions including; reservoirs and methods of transmission, prevailing local living conditions and customs (Li et al., 2007, Souppart et al., 2010).

In the current in vitro drug assay, the non-treated control group (I) showed that the mean Blastocystis count/ml was 20.11 × 104 ± 20.25 at 24 h. It significantly peaked to reach 48.61 × 104 ± 23.57 at 48 h, then the growth declined to 36.97 × 104 ± 20.36 at 72 h. In parallel, viability profile progressed in a similar manner, where viable Blastocystis/ml peaked to reach 43.69 × 04 ± 19.80 at 48 h and then declined to 34.19 × 104 ± 18.44 at 72 h. Many authors reported the same progress of growth and viability profiles of the untreated cultures (Yakoob et al., 2011, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013, Roberts et al., 2015).

Results of the solvent control group (II) revealed that, at all studied intervals, DMSO 1% did not induce any significant impact neither on Blastocystis growth nor on its viability profiles, as compared to the non-treated control group (I). Similarly, DMSO 1% used by Girish et al. (2015) showed no effect on Blastocystis growth. Likewise, other drug solvents such as 70% and 95% ethanol also showed no effect on parasite growth (Ramadan and Al Khadrawy, 2003, Vital and Rivera, 2009).

In the present study, MTZ was used as the standard therapeutic control. Results of group (III) demonstrated that Blastocystis multiplication was inhibited by 89.78% using the intermediate dose of MTZ at 72 h while using the highest dose (250 µg/ml) showed 89.14% and 95.43% percentages inhibition of multiplication at 48 h and 72 h, respectively. The percentage inhibition of Blastocystis viability was more than 90% with the intermediate dose at 72 h (94.65%) and with the highest dose at 48 and 72 h (94.71% and 97.72%, respectively). It has been reported that MTZ eliminated Blastocystis through inhibiting its nucleic acid synthesis (Nasirudeen et al., 2004, Raman et al., 2016). Different studies tested the sensitivity of Blastocystis to various doses of MTZ (Yakoob et al., 2011, El Deeb et al., 2012, Roberts et al., 2015, Raman et al., 2016, El-Sayed et al., 2017). Although total clearance of Blastocystis was not achieved by Roberts et al. (2015), even at 1000 µg/ml MTZ, other authors achieved it by lower concentrations (El Deeb et al., 2012, Mokhtar et al., 2016). Variability in response and susceptibility to the drug can be explained by different geographical locations or intra-subtype differences, which may be attributed to the presence of different alleles in each subtype (El-Sayed et al., 2017).

The in vitro effect of SMV on multiplication and viability of Blastocystis revealed that it induced progressive dose and duration dependent inhibitory effects. At 24 h, both growth and viability retardation have started. The highest inhibition of Blastocystis multiplication was achieved by the intermediate dose after 72 h (95.19%) and by the highest dose after 48 and 72 h (92.64% and 98.35%, respectively). In parallel, the highest inhibition of Blastocystis viability was achieved by the intermediate dose after 72 h (98.30%) and the highest dose after 48 and 72 h (97.57% and 99.77%, respectively). The impact of SMV on the inhibition of Blastocystis multiplication and viability was non-statistically significant when compared to MTZ at the respective concentrations and durations.

The current results could be presumably explained through the documented impact of protease inhibitors as antimicrobial agents. This is supported by Venturini et al., 2000, McKerrow et al., 2008, Hussein et al., 2009. Several cysteine protease inhibitors proved to be influential against in vitro Blastocystisʹ growth and viability. It was recorded that 99.74% inhibition of Blastocystis multiplication and 91% viability inhibition have been achieved by the highest dose of a cysteine protease inhibitor, at 72 h, and both parameters were abolished at 96 h (Eida et al., 2008). Similar results were reported by Al-Mohammed et al. (2013) who found that cysteine proteases inhibitors rendered Blastocystis non-viable. Protozoal growth retardation by serine protease inhibitors was successively documented (Dudley et al., 2008, Makioka et al., 2009). In Blastocystis, serine protease has been proven to play a critical effect on the pro-inflammatory cytokines expression and the protein kinase activation, as deduced from the in vitro incubation of Blastocystis with serine protease inhibitors (Lim et al., 2014).

For verifying the inhibitory extent of SMV on Blastocystis viability, re-culturing in fresh media revealed that the highest concentration of SMV (200 µg/ml), at the three studied intervals, and the intermediate concentration (150 µg/ml), at 48 and 72 h, were cytocidal to Blastocystis. On the other hand, the intermediate concentration (150 µg/ml), at 24 h, and the least concentration of SMV (100 µg/ml), at the three studied intervals, were only cytostatic, as Blastocystis resumed its growth after re-culturing. “Viable non-re-culturable cells” are these which have intact membranes, that retain their metabolic activities, yet, lose their ability to produce progenies (Nyström, 2001, Allegra et al., 2008, Rousseau et al., 2018). In agreement with the current results, Eida et al. (2008) demonstrated that a high concentration of NaNO2, as an anti-protease, was cytotoxic to Blastocystis growth in vitro, while at low concentration, the incomplete inhibitory effect was found as Blastocystis resumed growth after NaNO2 had been ceased.

On correlating the SMVʹs inhibitory effects on growth, viability and re-culture of Blastocystis, the most efficient dose and duration of SMV against ST3 Blastocystis turned out to be 150 µg/ml for 72 h. On trying this dose and duration on ST1 and ST2, growth was inhibited by 94.83% and 94.74%, respectively, as compared to 95.19% in ST3. The viability of ST1 and ST2 was inhibited by 98.09% and 97.96%, respectively, as compared to 98.30% in ST3. No viable Blastocystis was detected on re-culturing of ST1, ST2, and ST3 previously exposed to this dose. These results showed that there was no significant difference between the inhibition of Blastocystis growth, viability and re-culture in ST1 and ST2 Blastocystis when compared to ST3. Similarly, Girish et al. (2015) reported uniform inhibition among different Blastocystis subtypes. On the contrary, other anti-Blastocystis protease inhibitors induced variable effects on different Blastocystis subtypes (Al-Mohammed et al., 2013, Mokhtar et al., 2019). Subtype dependent variation might explain the variable response of different Blastocystis subtypes to the same drug in vitro (Mokhtar et al., 2019).

A morphological study was done using both light microscopic examination and electron microscopic verification. Different Blastocystis forms were detected (Abou El Naga and Negm, 2001). Of them; vacuolar, granular and cystic forms were detected in the untreated cultures. The vacuolar form was the most commonly detectable form followed by the granular form. These results are in agreement with Souppart et al., 2009, Mehta et al., 2015, Darabian et al., 2016. Granular form persisted after MTZ drug testing because, as reported, MTZ induces apoptosis, where granular formation is a self-regulatory mechanism of Blastocystis during apoptosis to produce high number of viable cells (Dhurga et al., 2016). This mechanism may underlie the resistance to MTZ as being stated by Haresh et al. (1999). However, after exposure to SMV, the granular form has disappeared and was replaced by the amoeboid form. The disappearance of the granular form may be attributed to the fact that serine protease inhibitors induce necrotic cell death (Al-Mohammed et al., 2013). The existence of amoeboid form has been formerly linked to drug-treated cultures (Kumar and Tan, 2013). It was described as a dying cell by Yason and Tan (2018) that could explain its presence after SMV drug trial.

In the present SEM study, SMV-treated Blastocystis verified the light microscopic findings that some of Blastocystis showed irregular amoebic forms, while others preserved their round or oval shape with remarkable convolutions and folding on their surfaces. This finding agreed with Raman et al. (2016) who treated Blastocystis with MTZ. Some treated Blastocystis showed membrane pores that could lead to cytoplasmic leakage, which was also previously detected by Yason et al. (2016) when Blastocystis was treated with LL-37 (a colonic antimicrobial peptide).

Transmission electron microscopy revealed that SMV, in the present study, induced Blastocystis necrosis and cell death. Necrotic cells were electron-lucent, the central vacuole seemed devoid of any electron-dense particles and some showed plasma membrane rupture. These abnormal findings were in agreement with the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death that described the term “necrotic cell death” as being morphologically characterized by plasma membrane rupture and subsequent loss of intracellular contents (Nasirudeen et al., 2004, Kroemer et al., 2009, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013). The same necrotic findings were detected when Blastocystis was treated with proteases inhibitors by Al-Mohammed et al. (2013). On the other hand, authors reported the apoptotic effect of MTZ on Blastocystis (Nasirudeen et al., 2004, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013). Apoptotic cell death includes nuclear condensation, cell shrinkage, deposition of membrane-bound apoptotic bodies and heavy vacuolization appears (Nasirudeen et al., 2004, Al-Mohammed et al., 2013). Explanation of these discrepancies between the effects of MTZ and SMV by TEM may be due to different mechanisms of action of both drugs on Blastocystis. On entering the targeted cells, MTZʹs cytotoxic form disrupts the DNA of the parasite (Nasirudeen et al., 2004, Raman et al., 2016). On the other hand, SMV acts by inhibition of serine proteases, and the central vacuole of Blastocystis is a reservoir for proteases as was reported by Puthia et al. (2008).

5. Conclusion

Results of the present study proved the promising in vitro anti-Blastocystis effect of simeprevir. The most effective studied dose and duration of SMV (150 µg/ml dose for 72 h) proved its efficacy against ST1, ST2, and ST3, which are the most commonly reported subtypes in Egypt. This finding saves the need for molecular subtyping in developing countries, before starting Blastocystis treatment. Moreover, SMV-induced necrosis of the targeted organism is a promising advantage, versus the reported MTZ- induced apoptotic and granular formation, which underlays the risk of therapeutic resistance.

Further studies are recommended for subtype analysis of molecularly unidentified strains and for applying the effect of the most efficient dose and duration of SMV on them. Testing the precise effect of SMV on resistant isolates, their molecular verification, their biochemical analysis, and their electron microscopic study is recommended. Performing a biochemical study of protease level of ST1, ST2, and ST3 for further verification of the mode of action of SMV is mandatory.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval and Informed consent

Stool specimens were collected as part of routine clinical examination of patients, according to the national guidelines. Informed consents were sought from patients and approval from the institutional ethics committee was obtained.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abaza S., Rayan H., Soliman R., Nemr N., Mokhtar A. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis spp. isolates from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in Suez Canal University Hospitals, Ismailia, Egypt. Parasitol. United. J. 2014;7(1):56. doi: 10.4103/1687-7942.139691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abou El Naga I.F., Negm A.Y. Morphology, histochemistry and infectivity of Blastocystis hominis cyst. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2001;31(2):627–635. PMID: 11478461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adao D.E., Rivera W.L. Recent advances in Blastocystis sp. research. Philipp. Sci. Lett. 2018;11(1):39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohammed H.I., Hussein E.M., Aboulmagd E. Effect of Green Tea Extract and Cysteine Proteases Inhibitor (E-64) on Symptomatic Genotypes of Blastocystis hominis in vitro and in Infected Animal Model. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2013;2(12):228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso Y., Monzote L. HIV protease inhibitors: Effect on the opportunistic protozoan parasites. Open. Med. Chem. J. 2011;5:40–50. doi: 10.2174/1874104501105010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegra S., Berger F., Berthelot P., Grattard F., Pozzetto B., Riffard S. Use of flow cytometry to monitor Legionella viability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7813–7816. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01364-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfaram S., Daryani A., Sarvi S., Pagheh A.S., Hosseini S.A., Saberi R., Hoseiny S.M., Soosaraei M., Sharif M. Geospatial analysis and epidemiological aspects of human infections with Blastocystis hominis in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Epidemiol. Health. 2019;41:e2019009. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyhan Y.E., Yilmaz H., Cengiz Z.T., Ekici A. Clinical significance and prevalence of Blastocystis hominis in Van. Turkey. Saudi Med. J. 2015;36(9):1118–1121. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.9.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle C.M., Varughese J., Weiss L.M., Tanowitz H.B. Blastocystis: to treat or not to treat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54(1):105–110. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabian A., Berenji F., Ganji A., Fata A., Jarahi L. Association between Blastocystis hominis and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Int. J. Med. Res. Hlth. Sci. 2016;5(9):102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Alam M.N., Paik D., Karmakar K., De T., Chakraborti T. Protease inhibitors in potential drug development for Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;50(5):363–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delshad A., Saraei M., Alizadeh S.A., Niaraki S.R., Alipour M., Hosseinbigi B., Bozorgomid A., Hajialilo E. Distribution and molecular analysis of Blastocystis subtypes from gastrointestinal symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in Iran. Afr. health sci. 2020;20(3):1179–1189. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i3.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhurga D.B., Suresh K., Tan T.C. Granular Formation during Apoptosis in Blastocystis sp. Exposed to Metronidazole (MTZ) PLoS. One. 2016;11(7):e0155390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda A., Kosik-Bogacka D., Lanocha-Arendarczyk N., Kołodziejczyk L., Lanocha A. The prevalence of Blastocystis hominis and other protozoan parasites in soldiers returning from peacekeeping missions. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;92(4):805–806. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R., Alsam S., Khan N.A. The role of proteases in the differentiation of Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS. Microbiol. lett. 2008;286(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L.A., Andrews K.T., McCarthy J.S., Wright J.M., Skinner-Adams T.S., Upcroft P. The activity of protease inhibitors against Giardia duodenalis and metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2007;29(1):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eassa S.M., Ali H.S., El Masry S.A., Abd El-Fattah A.H. Blastocystis hominis among immunocompromised and immunocompetent children in Alexandria, Egypt. Ann. Clin. Lab. Res. 2016;4:2. doi: 10.21767/2386-5180.100092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eida O.M., Hussein E.M., Eida A.M., El-Moamly A.A., Salem A.M. Evaluation of the nitric oxide activity against Blastocystis hominis in vitro and in vivo. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2008;38(2):521–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Deeb H.K., Al Khadrawy F.M., Abd El-Hameid A.K. Inhibitory effect of Ferula asafoetida L. (Umbelliferae) on Blastocystis sp. subtype 3 growth in vitro. Parasitol. Res. 2012;111(3):1213–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elghareeb A.S., Younis M.S., El Fakahany A.F., Nagaty I.M., Nagib M.M. Laboratory diagnosis of Blastocystis spp. in diarrheic patients. Trop. Parasitol. 2015;5(1):36–41. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.149919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Marhoumy S.M., El-Nouby K.A., Shoheib Z.S., Salama A.M. Prevalence and diagnostic approach for a neglected protozoon Blastocystis hominis. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015;5(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/s2222-1808(14)60626-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Safadi D., Cian A., Nourrisson C., Pereira B., Morelle C., Bastien P., Bellanger A.P., Botterel F., Candolfi E., Desoubeaux G., Lachaud L., Morio F., Pomares C., Rabodonirina M., Wawrzyniak I., Delbac F., Gantois N., Certad G., Delhaes L., Poirier P., Viscogliosi E. Prevalence, risk factors for infection and subtype distribution of the intestinal parasite Blastocystis sp. from a large-scale multi-center study in France. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;26(451) doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1776-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsayad M.H., Tolba M.M., Argiah H.A., Gaballah A., Osman M.M., Mikhael I.L. Electron microscopy of Blastocystis hominis and other diagnostic approaches. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2019;49(2):373–380. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed S.H., Amer N., Ismail S., Ali I., Rizk E., Magdy M., El-Badry A.A. In vitro and in vivo anti-blastocystis efficacy of olive leaf extract and bee pollen compound. Res. J. Parasitol. 2017;12(2):33–44. doi: 10.3923/jp.2017.33.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shewy K.A., El-Hamshary E.M., Abaza S.M., Eida A.M. Prevalence and clinical significance of Blastocystis hominis among school children in Ismailia city. Egypt. J. Med. Sci. 2002;23:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Farghaly A., Hamza R.S., El-Aal N.F.A., Metwally S., Farag S.M. Prevalence, risk factors and comparative diagnostic study between immunofluorescence assay and ordinary staining techniques in detection of Blastocystis hominis in fecal samples. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2017;47(3):701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Forsell J., Granlund M., Stensvold C.R., Clark C.G., Evengård B. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis isolates in Swedish patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:1689–1696. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad S.A., Basyoni M.M., Fahmy R.A., Kobaisi M.H. The pathogenic role of different Blastocystis hominis genotypes isolated from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;12(4):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L.S. Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. 4th ed. AMS press; Washington DC: 2007. Examination of faecal specimens; pp. 782–825. [Google Scholar]

- Girish S., Kumar S., Aminudin N. Tongkat Ali (Eurycomalongifolia): A possible therapeutic candidate against Blastocystis sp. Parasit. Vectors. 2015;8:332. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0942-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haresh K., Suresh K., Khairul Anus A., Saminathan S. Isolate resistance of Blastocystis hominis to metronidazole. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1999;4(4):274–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein E.M., Dawood H.A., Salem A.M., Atwa M.M. Antiparasitic activity of cystine protease Inhibitor E-64 against Giardia lamblia excystation in vitro and in vivo. Egypt. J. Soc. Parasitol. 2009;39:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo L., Helle F., Francois C., Castelain S., Duverlie G., Brochot E. Simeprevir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 2014;7:241–249. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S52715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez P.A., Jaimes J.E., Ramírez J.D. A summary of Blastocystis subtypes in North and South America. Parasit. Vectors. 2019;12(1):376. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3641-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademvatan S., Masjedizadeh R., Yousefi-Razin E., Mahbodfar H., Rahim F., Yousefi E., Foroutan M. PCR-based molecular characterization of Blastocystis hominis subtypes in southwest of Iran. J. Infect. Public. Health. 2018;11(1):43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnood S., Rafiei A., Saki J., Alizadeh K. Prevalence and Genotype Characterization of Blastocystis hominis Among the Baghmalek People in Southwestern Iran in 2013–2014. Jundishapur. J. Microbiol. 2015;8(10):e23930. doi: 10.5812/jjm.23930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz S., Balakrishnan N., Read C.B., Vidakovic B. 2nd ed. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, N.J.: 2006. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Vandenabeele P., Abrams J., Alnemri E.S., Baehrecke E.H., Green D.R. Classification of cell death: Recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2009. Cell. Death. Differ. 2009;16:3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Tan, T.C., 2013. Romancing Blastocystis: A 20-Year Affair. In Y. A. L. Lim & I. Vythilingam (Eds.). Parasites and their vectors: A special focus on Southeast Asia.131-154.

- Lee I.L., Tan T.C., Tan P.C., Nanthiney D.R., Biraj M.K., Surendra K.M., Suresh K.G. Predominance of Blastocystis spp. subtype 4 in rural communities. Nepal. Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:1553–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepczynska M., Bialkowska J., Dzika E., Piskorz-Ogorek K., Korycinska J. Blastocystis: how do specific diets and human gut microbiota affect its development and pathogenicity? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;36(9):1531–1540. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2965-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.H., Zhang X.P., Lv S., Zhang L., Yoshikawa H., Wu Z., Zhou X.N. Crosssectional surveys and subtype classification of human Blastocystis isolates from four epidemiological settings in China. Parasitol. Res. 2007;102:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M.X., Png C.W., Tay C.Y.B., Teo J.D.W., Jiao H., Lehming N., Zhang Y. Differential regulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression by mitogen-activated protein kinases in macrophages in response to intestinal parasite infection. Infect. Immun. 2014;82(11):4789–4801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02279-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.I., Lenzo O., Fanning G., Verbinnen T., Delouvroy F., Scholliers A. In vitro activity and preclinical profile of TMG435350, a potent hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2009;53(4):1377–1385. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01058-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makioka A., Kumagai M., Kobayashi S., Takeuchi T. Involvement of serine proteases in the excystation and metacystic development of Entamoeba invadens. Parasitol. Res. 2009;105(4):977. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malheiros A.F., Stensvold C.R., Clark C.G., Braga G.B., Shaw J.J. Short report: molecular characterization of Blastocystis obtained from members of the indigenous Tapirapé ethnic group from the Brazilian Amazon region, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:1050–1053. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney J.G., Lombard J.E., Urie N.J., Shivley C.B., Santin M. Zoonotic and genetically diverse subtypes of Blastocystis in US pre-weaned dairy heifer calves. Parasitol. Res. 2019;118(2):575–582. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-6149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerrow J.H., Rosenthal P.J., Swenerton R., Doyle P. Development of protease inhibitors for protozoan infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2008;21(6):668–672. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328315cca9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta R., Koticha A., Kuyare S., Mehta P. Are we neglecting Blastocystis hominis in patients having irritable bowel syndrome. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Soc. 2015;4(64):1164–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Meloni D., Sanciu G., Poirier P., El Alaoui H., Chabé M., Delhaes L. Molecular subtyping of Blastocystis spp. isolates from symptomatic patients in Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2011;109:613–619. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A.M., Ahmed M.A., Ahmed S.A., Al-Semany S.A., Alghamdi S.S., Zaglool D.A. Predominance and association risk of Blastocystis hominis subtype I in colorectal cancer: a case control study. Infect. Agent. Cancer. 2017;12:21. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0131-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtar A.B., El-Gayar E.K., Habib E.S. In vitro anti-protozoal activity of propolis extract and cysteine proteases inhibitor (phenyl vinyl sulfone) on Blastocystis species. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2016;46:261–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtar A.B., Ahmed S.A., Eltamany E.E., Karanis P. Anti-Blastocystis activity in vitro of Egyptian herbal extracts (family: asteraceae) with emphasis on artemisia judaica. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2019;16(9):1555. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi A., Haghighi A., Mojarad E.N., Zayeri F., Alebouyeh M., Khazan H., Kazemi B., Zali M.A. Genetic variability of Blastocystis spp. isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals in Iran. Parasitol. Res. 2012;111:2311–2315. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento S.A., Moitinho Mda L. Blastocystis hominis and other intestinal parasites in a community of Pitanga City, Paraná State. Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao. Paulo. 2005;47:213–217. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652005000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasirudeen A.M., Hian Y.E., Singh M., Tan K.S. Metronidazole induces programmed cell death in the protozoan parasite Blastocystis hominis. Microbiology. 2004;150(1):33–43. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyström T. Not quite dead enough: on bacterial life, culturability, senescence, and death. Arch. Microbiol. 2001;176:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s002030100314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M., El Safadi, D., Cian, A., Benamrouz, S., Nourrisson, C., Poirier, P., Pereira, B., Razakandrainibe, R., Pinon, A., Lambert, C., Wawrzyniak, I., Dabboussi, F., Delbac, F., Favennec, L., Hamze, M., Viscogliosi, E., Certad, G., 2016. Prevalence and risk factors for intestinal protozoan infections with Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Blastocystis and Dientamoeba among schoolchildren in Tripoli, Lebanon. PLoS Negl .Trop. Dis. 14;10(3):e0004496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004496. Erratum in: PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10: e0004643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Poirier P., Wawrzyniak I., Vivares C.P., Delbac F., El Alaoui H. New insights into Blastocystis spp.: a potential link with irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS. Pathog. 2012;8(3):e1002545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthia M.K., Lu J., Tan K.S. Blastocystis ratti contains cysteine proteases that mediate interleukin-8 response from human intestinal epithelial cells in an NF-kappa B-dependent manner. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7(3):435–443. doi: 10.1128/EC.00371-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamanikam A., Hooi H.S., Kudva M., Samudi C., Kumar S. Resistance towards metronidazole in Blastocystis sp.: A pathogenic consequence. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0212542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan N.I., Al Khadrawy F.M. The in vitro effect of Assafoetida on Trichomonas vaginalis. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2003;33(2):615–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman K., Kumar S., Chye T.T. Increase number of mitochondrion-like organelle in symptomatic Blastocystis subtype 3 due to metronidazole treatment. Parasitol. Res. 2016;115(1):391–396. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez J.D., Sánchez A., Hernández C., Flórez C., Bernal M.C., Giraldo J.C., Reyes P., López M.C., García L., Cooper P.J., Vicuña Y., Mongi F., Casero R.D. Geographic distribution of human Blastocystis subtypes in South America. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;41:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T., Stark D., Harkness J., Ellis J. Subtype distribution of Blastocystis isolates identified in a Sydney population and pathogenic potential of Blastocystis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;32:335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1746-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T., Bush S., Ellis J., Harkness J., Stark D. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Blastocystis. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2015;59(8):4417–4423. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04832-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau A., La Carbona S., Dumetre A., Robertson L.J., Gargala G., Escotte-Binet S., Aubert D. Assessing viability and infectivity of foodborne and waterborne stages (cysts/oocysts) of Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Toxoplasma gondii: a review of methods. Parasite. 2018;25:14. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2018009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar U., Shanthi M. Blastocystis: Consensus of treatment and controversies. Trop. Parasitol. 2013;3(1):35–39. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyer A., Karasartova D., Ruh E., Güreser A.S., Turgal E., Imir T., Taylan-Ozkan A. Epidemiology and Prevalence of Blastocystis spp. in North Cyprus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;96(5):1164–1170. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souppart L., Sanciu G., Cian A., Wawrzyniak I., Delbac F., Capron M., Viscogliosi E. Molecular epidemiology of human Blastocystis isolates in France. Parasitol. Res. 2009;105(2):413–421. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souppart L., Moussa H., Cian A., Sanciu G., Poirier P., El Alaoui H., Viscogliosi E. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis isolates from symptomatic patients in Egypt. Parasitol. Res. 2010;106(2):505–511. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold C.R., Clark C.G. Pre-empting Pandora's Box: Blastocystis Subtypes Revisited. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36(3):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar S., Trembling P.M., Dusheiko G.M. TMC435 for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2012;21(8):1193–1209. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.690392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathaisong U., Siripattanapipong S., Mungthin M., Pipatsatitpong D., Tan-ariya P., Naaglor T., Leelayoova S. Identification of Blastocystis subtype 1 variant in the Home for girls, Bangkok. Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013;88:352–358. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturini G., Cloasanti M., Salvati L., Gradoni L., Ascenze P. Nitric oxide inhibits falcipain, the Plasmodium falciparum trophozoite cysteine protease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;267:190–193. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vital P.G., Rivera W.L. Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of Chromolaena odorata (L.f.) King and Robinson and Uncaria perrottetii (A.Rich) Merr. Extracts. J. Med. Plants. Res. 2009;3(7):511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J., Abbas Z., Beg M.A., Naz S., Awan S., Hamid S., Jafri W. In vitro sensitivity of Blastocystis hominis to garlic, ginger, white cumin, and black pepper used in diet. Parasitol. Res. 2011;109(2):379–385. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2265-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yason J.A., Ajjampur S.S.R., Tan K.S.W. Blastocystis Isolate B Exhibits Multiple Modes of Resistance against Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37. Infect. Immun. 2016;84(8):2220–2232. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00339-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yason J., Tan K. Membrane Surface Features of Blastocystis Subtypes. Genes. (Basel). 2018;9(8) doi: 10.3390/genes9080417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti A.D.S., Malheiros A.F., de Matos T.A., Longhi F.G., Moreira L.M., Silva S.L., Castrillon S.K.I., Ferreira S.M.B., Ignotti E., Espinosa O.A. Prevalence of Blastocystis sp. infection in several hosts in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit. Vectors. 2020;14:30. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-3900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhang S., Qiao J., Wu X., Zhao L., Liu Y., Fan X. Ultrastructural insights into morphology and reproductive mode of Blastocystis hominis. Parasitol. Res. 2012;110(3):1165–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2607x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]