Significance

Most of our knowledge about microbial physiology originates from studying fast-growing, heterotrophic bacteria. Yet, microorganisms are energy-limited in many natural environments and grow slowly or persist in a nongrowing state. Microorganisms adapted to oligotrophic lifestyles are phylogenetically diverse and often possess biochemically unique and highly niche-specialized metabolisms. In a systems-level study, we discovered a strategy for acclimation to slow growth in a chemolithoautotrophic archaeon. In contrast to relying on gene regulation like metabolically versatile, heterotrophic model bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Methanococcus maripaludis responds to energy limitation by redistributing energy for cellular maintenance and changing catabolic and ribosomal activities. The alternative resource allocation strategy presented here does not follow the canonical growth rate–dependent physiological regulations.

Keywords: slow growth, methanogen, proteome allocation, maintenance energy, ribosome activity

Abstract

Most microorganisms in nature spend the majority of time in a state of slow or zero growth and slow metabolism under limited energy or nutrient flux rather than growing at maximum rates. Yet, most of our knowledge has been derived from studies on fast-growing bacteria. Here, we systematically characterized the physiology of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis during slow growth. M. maripaludis was grown in continuous culture under energy (formate)-limiting conditions at different dilution rates ranging from 0.09 to 0.002 h−1, the latter corresponding to 1% of its maximum growth rate under laboratory conditions (0.23 h−1). While the specific rate of methanogenesis correlated with growth rate as expected, the fraction of cellular energy used for maintenance increased and the maintenance energy per biomass decreased at slower growth. Notably, proteome allocation between catabolic and anabolic pathways was invariant with growth rate. Unexpectedly, cells maintained their maximum methanogenesis capacity over a wide range of growth rates, except for the lowest rates tested. Cell size, cellular DNA, RNA, and protein content as well as ribosome numbers also were largely invariant with growth rate. A reduced protein synthesis rate during slow growth was achieved by a reduction in ribosome activity rather than via the number of cellular ribosomes. Our data revealed a resource allocation strategy of a methanogenic archaeon during energy limitation that is fundamentally different from commonly studied versatile chemoheterotrophic bacteria such as E. coli.

Archaea represent the third domain of life and include microbes that differ substantially from other microorganisms in terms of metabolism, cellular biology, and molecular biology as well as the physicochemical environment they inhabit. Methanogenesis is a prevalent example of an ancient metabolism that is deeply rooted in the archaeal tree of life and cannot be found outside this domain (1). While most studies have focused on the biochemistry and cell biology of archaea, fundamental understanding and systems-level study of their acclimation to persistence and slow growth have been absent. Most natural microbial environments are limited by flux of energy, ranging from high-flux environments with high turnover of organic matter, such as animal guts, microbial mats, and organic matter–rich top soils and sediments to extremely low-flux environments, such as subseafloor sediments, deep glacial ice, and the continental subsurface (2–5). Despite the low fluxes, the latter environments have enormous influence on global biogeochemical cycles, including the carbon cycle, and contain most of Earth’s total microbial biomass (6). Archaea are often found in low-flux environments (7), and it has been proposed that adaptations to energy limitation dictate the ecology and evolution of the Archaea (8). Under low energy flux conditions, the allocation of cellular energy to diverse physiological processes is shifted from growth to maintenance, leading to a decrease in biomass yield at slower growth rates (9–11). Because protein synthesis is the most costly cellular process and directly related to growth rate, an efficient allocation of the cellular proteome is key for efficient energy utilization during low energy and nutrient flux. Enzyme levels have been postulated to be under selection to minimize protein expression costs (12–14). However, these fundamental insights into microbial physiology were primarily derived from studies of versatile, heterotrophic bacteria when growing under non-energy-limited conditions near maximum growth rate (μmax), which do not reflect strategies relevant in low-energy conditions found in many ecological niches.

At lower nutrient flux, Escherichia coli increases expression of catabolic enzymes and transporters while decreasing expression of anabolic pathways as a strategy for competitive and efficient nutrient uptake and use (12, 13). During fast growth, E. coli ferments carbohydrates even in the presence of oxygen, whereas during slower growth the additionally expressed respiratory proteome enables a more complete, efficient substrate utilization. This proteome reallocation has been rationalized as an effort to optimize growth rate in response to nutrient flux, as the complete respiration pathway requires a larger catabolic proteome than fermentation, thereby competing with anabolic growth processes for proteome space (12, 13). In E. coli, the ribosome level correlates closely in a near-linear relationship with growth rate (15–19). Similar regulations have been observed in other versatile chemoheterotrophic microbes such as Bacillus (20) and yeast (21, 22). Other than proteome regulation, cells grown at lower nutrient flux typically show morphological changes leading to smaller cells with decreased macromolecular content as a strategy to increase nutrient uptake and intracellular metabolite and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentrations by increasing the surface-to-volume ratio (23–25). This empirical relationship between growth rate and cell size is known as the nutrient growth law (26) and is thought to be generally applicable, even in slow growing bacteria capable of symbiotic nitrogen fixation (27, 28) or obligate phototrophs (29).

Based on these correlations and findings of physiological regulation, microbial ribosome content has been consistently used as a measurement for microbial activity (30). However, the assumption that cellular ribosome content is a proxy for microbial growth or activity in the environment was shown to have limitations (reviewed in ref. 30). rRNA content does not directly correlate with growth rate in marine cyanobacteria (31, 32) and phototrophic and nonphototrophic Proteobacteria (33, 34). Additionally, the relationship between rRNA concentration and non-growth-related microbial activity, such as motility, communication, stress defense, osmoregulation, macromolecule turnover, or energy spilling reactions (11), have not been investigated, even though microbial maintenance activity may contribute significantly to ecosystem function (35).

Therefore, it is unclear whether the correlations and physiological traits observed in versatile chemoorganotrophic bacteria hold true outside of competitive, high-flux environments. In this study, we used the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis as a model microorganism to reveal physiological traits during slow growth. M. maripaludis is a hydrogenotrophic, strictly anaerobic methanogenic archaeon that can utilize either H2 and CO2 or formate as catabolic substrates. Therefore, it is highly niche-specialized, as methanogenesis is the only catabolic pathway (36–38). Importantly, the methanogenesis pathway of this archaeon cannot be partitioned into shorter pathways unlike glucose metabolism in E. coli, which can be either respiratory and/or fermentative. The parent strain of the M. maripaludis strain used in this study (S2-derivative MM901) was isolated from an intertidal region on the bank of the Latham River (GA) (37), where selective pressure on a robust “starvation” physiology in response to a periodically changing environment following tides is likely predominant.

Results

Growth Yield and Maintenance Energy.

We conducted a comprehensive, systems-level study on the physiology of M. maripaludis during a broad range of growth rates using formate as catabolic substrate (4 HCO2− + 1 CO2 + 4 H+ → 1 CH4 + 4 CO2 + 2 H2O). Water-soluble formate was chosen over H2 as the catabolic electron donor to circumvent effects induced by hydrogen gas mass transfer limitations (39). It also ensured that energy, rather than carbon (CO2), was growth limiting as the CO2 used for carbon fixation is produced in excess during formate metabolism. Formate (electron donor)-limited, anoxic chemostats of M. maripaludis were operated at dilution rates in the range of 1 to 39% relative to μmax (0.23 h−1) of an exponentially growing batch culture using the same medium with a saturating amount of formate (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1). This μmax is close to the highest growth rates of 0.24 to 0.34 h−1 reported for this strain in similar minimal media, corresponding to doubling times between 2 and 3 h (38, 40).

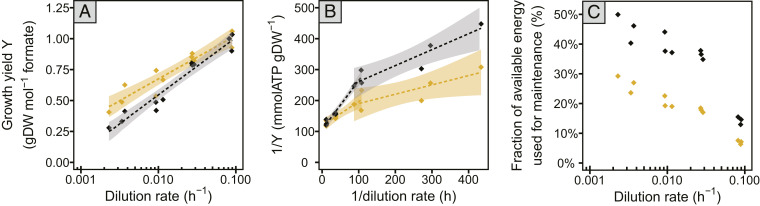

Fig. 1.

Growth yield and maintenance energy estimates. Values are shown based on observed cell densities (black diamonds) and corrected for rate of cell lysis (gold diamonds). Shaded areas depict 5% confidence level intervals. (A) Apparent molar growth yield (black diamonds) significantly correlated logarithmically with dilution rate (y = 0.20ln(x) + 1.47, R2 = 0.95, P value < 0.01). The cell lysis-corrected yield (gold diamonds) shows a less steep decline with growth rate (y = 0.15ln(x) + 1.38, R2 = 0.90, P value < 0.01). (B) Double reciprocal graph of yield and growth rate. The slope of the linear regression is used to estimate energy spent on maintenance. Using cellular growth yield, maintenance energy costs seem to be nonlinear over different growth rates and are approximated using two separate linear regressions at higher (y = 1.61x + 106, R2 = 0.96, P value < 0.01) and at lower growth rates (y = 0.51x + 213, R2 = 0.87, P value < 0.01). Using cell lysis-corrected yield, the slopes of the linear relationships in the plot are less steep (y = 0.80x + 117, R2 = 0.78, P value < 0.05 at higher growth rates; y = 0.29x + 162, R2 = 0.66, P value < 0.05 at lower growth rates). (C) Estimated fraction of available energy used for maintenance.

The growth yield of M. maripaludis decreased logarithmically with dilution rates. Cell density decreased from an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.59 ± 0.02 at higher dilution rates (0.087 ± 0.003 h−1), which is close to the maximum cell density reached in batch culture in this growth medium, to 0.20 ± 0.03 at lower dilution rates (0.003 ± 0.001 h−1). Loss in biomass at slower growth is in part due to cell lysis as revealed by measurement of extracellular DNA and protein concentrations (SI Appendix, Note S1 and Fig. S1). By comparing these values with macromolecular content in viable cells, we estimated the lysed biomass, which alone could not explain the decrease of biomass at slower growth (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Based on the lysed biomass, lysis rates were estimated (SI Appendix, Note S1). We did not observe a statistically significant dilution rate dependence of lysis rate, rather, we estimated a constant lysis rate of 0.002 h−1 (SI Appendix, Note S1).

Maintenance energy or the maintenance coefficient (41), defined as the amount of catabolic substrate used for maintenance (and converted to ATP for comparability), was estimated from the slope of a linear regression of the inverse of growth yield on the inverse of growth rate. Interestingly, the relationship was nonlinear, indicating different maintenance energy requirements at different growth rates (Fig. 1B). When approximated with biphasic linear regression, the absolute amount of cellular energy spent on maintenance was higher at high growth rates, 1.61 mmol ATP gDW−1 h−1 versus 0.51 mmol ATP gDW−1 h−1 at slow growth (Fig. 1B). The relative amount of energy used for maintenance was significantly higher at lower growth rates (from 49% at low to 12% at high growth rates) (Fig. 1C). Correcting for the observed rate of cell lysis and, therefore, only accounting for energy spent on production of biomass in intact cells, maintenance energy during fast growth was 0.80 mmol ATP gDW−1 h−1, while during slow growth it was 0.29 mmol ATP gDW−1 h−1. The cell lysis corrected estimated fraction of energy used for maintenance ranged from 7% at fast to 29% at slow growth (Fig. 1 B and C).

Proteome Composition.

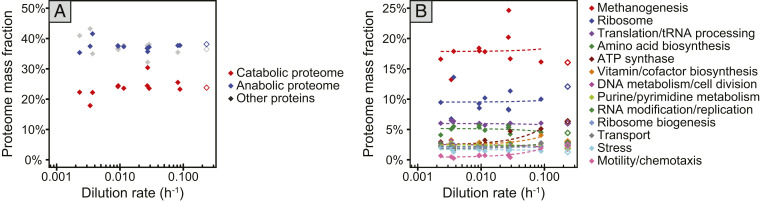

In marked contrast to E. coli, the overall proteome composition did not change significantly as a function of growth rate in M. maripaludis. A total of 872 proteins (51% of the genomically predicted 1,722 proteins) were detected and quantified against a labeled reference (Dataset S2). From this data set, we employed a coarse-graining analysis to approximate the abundance of functionally related groups of proteins to investigate resource allocation as a function of growth rate. The relative proteome space of the catabolic methanogenesis proteome, consisting of the enzymes of the methanogenesis pathway and ATP synthases, was stable at 24 ± 3% of the total proteome at all growth rates (Fig. 2A). The anabolic proteome, consisting mainly of the replication, transcription, and translation machineries as well as enzymes for monomer and cofactor biosynthesis, constituted 38 ± 1% of the total proteome and did not vary significantly with growth rate either. A more detailed analysis of proteome subsectors with a mass fraction of more than 2% of the total proteome also revealed largely invariant proteome allocation with respect to growth rate (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Of several sectors showing growth rate dependent trends, only one group tested significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (adjusted P value <0.05): the motility/chemotaxis sector, consisting of 12 proteins of the archaellum and 7 putative chemotaxis proteins, correlated positively with growth rate (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Dataset S2). At the single-protein level, only MMP0281, a hypothetical nucleotide binding protein, showed a significant negative correlation with growth rate (adjusted P value <0.05).

Fig. 2.

High-level overview of proteome composition at different growth rates. Sum of mass fractions of proteins organized into functional sectors, showing data from chemostat-grown cells (filled diamonds) and an exponential phase batch culture sample (open diamonds). (A) Proteome allocation to the two major proteome sectors, anabolism and catabolism. (B) Proteome allocation to subsystems comprising >2% of the total proteome in at least one sample. Dotted lines show linear regressions.

Methanogenesis.

Methane formation rates linearly correlated with the dilution rate (Fig. 2) as formate supplied with the growth medium was completely consumed. On average, 80% of formate-derived electrons were recovered in methane, and the remainder was presumably used for biomass formation. Based on the observed invariant catabolic proteome, we hypothesized that cells at lower growth rates should have the same metabolic potential for methane formation rates as fast-growing cells. Indeed, cells growing at different dilution rates, when sampled from the chemostat into anoxic Hungate tubes and spiked with 150 mM formate, catalyzed methane formation at rates similar to those of cells grown at high dilution rates and correspondingly high methanogenesis rates in the chemostat (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This capacity for instant, high-rate methanogenesis was also retained when de novo protein synthesis was inhibited by addition of 5 µg mL−1 pseudomonic acid (PA), an inhibitor of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (SI Appendix, Note S2). Interestingly however, at the lowest tested dilution rates of 0.002 to 0.004 h−1, the specific rate of methanogenesis in the cell suspensions was significantly reduced (Fig. 3). In addition, cells growing at dilution rates of <0.004 h−1 showed more than 6 h lag phase when exposed to a high concentration of formate, while the cells growing at higher rates all displayed a lag phase of less than 2 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Methanogenesis rates at different growth rates. Specific rates of methane formation during chemostat growth (black diamonds) linearly correlate with dilution rate (y = 208.14x + 1.59, R2 = 0.98, P value < 0.01; shaded area depicts 5% confidence level interval for predictions from linear model). Specific methanogenesis rates of cells transferred from continuous to batch culture with new substrate (150 mM formate) with (gold circles) or without (gray circles) inhibition of new protein synthesis by pseudomonic acid.

Cellular Content and Ribosomal Activity.

Consistent with an invariant anabolic proteome, macromolecular composition (i.e., DNA, RNA, and protein) of cells was constant at different growth rates. In M. maripaludis, total dry biomass contained ∼70% (range 50 to 95%) protein, 10% (range 7 to 15%) RNA, and 3% (range 2 to 4%) DNA (Fig. 4A). The apparent slight trend toward higher protein content at higher growth rates was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Macromolecular composition and cell size of M. maripaludis at different growth rates, showing data from chemostat-grown cells (filled diamonds) and an exponential phase batch culture sample (open diamonds). (A) Protein (black diamonds), RNA (gold diamonds), and DNA content (gray diamonds) of M. maripaludis at different growth rates. (B) Cell diameter of M. maripaludis at different growth rates determined by microscopy (black diamonds) and flow cytometry (gold diamonds). (C) Density plot of cell diameters determined by microscopy, averaged for different dilution rate: fast (F, 0.082 to 0.090 h−1), medium (M, 0.027 to 0.029 h−1), slow (S, 0.009 to 0.010 h−1) and very slow (XS, 0.002 to 0.004 h−1) and shown by dashed vertical lines.

Cell size, when independently determined by microscopy and flow cytometry, was largely invariant of growth rate with an average diameter of 1.21 µm at dilution rates above 0.009 h−1 (Fig. 4B). Cells grown at dilution rates below 0.004 h−1 were slightly bigger with an average diameter of 1.33 µm and showed considerably higher heterogeneity within samples (Fig. 4C). Chromosome copy number was on average 6 copies per cell as determined by flow cytometry (range 4 to 8), which is lower than previously reported (42). A similar absence of dramatic morphological changes has been reported in other microbes when facing starvation (43–49), suggesting that these microbes may exhibit a similar phenotype as M. maripaludis. The increase of cell size only at the lowest growth rates is similar to the morphological change observed in Lactococcus lactis and Bacillus subtilis at (near-)zero growth, possibly caused by the difficulty of completing cell division at low energy level and a prolonged cell cycle (43, 49). Such observations form a contrast to several versatile chemoheterotrophic microbes, which exhibit a positive correlation of cell size with growth rate (15, 23, 27, 50).

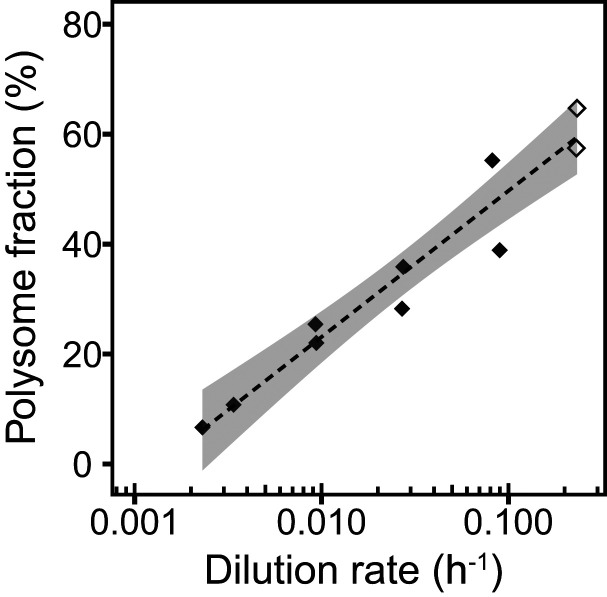

A closer examination of RNA content revealed that ribosomal RNA comprised a constant 80% (± 5%) fraction of total RNA at all growth rates. In context of constant levels of ribosomal proteins (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), this suggests a lack of regulation of ribosome synthesis in response to a reduction in protein synthesis at lower dilution rates. Indeed, amino acid deprivation imposed by PA treatment did not trigger cessation of net RNA accumulation in M. maripaludis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) as it does in bacteria that possess (p)ppGpp-based “stringent control” regulation (51–53). To investigate how M. maripaludis cells accommodate lower protein synthesis rates, we determined the fraction of polysomes as an indication of ribosomal activity (SI Appendix, Note S3 and Fig. S6). Decreasing growth rate correlated with a significant logarithmic decrease (P value <0.01) in the polysome fraction from 65 to 11% (Fig. 5). Considering the two orders of magnitude decrease in net protein synthesis rates across investigated dilution rates, such an approximate sixfold decrease in polysome fraction indicates a significant decrease in elongation rates of the working ribosomes as well. Direct measurements of translational elongation rates by pulse chase methods are hampered by the lack of prompt uptake of externally supplied amino acids into M. maripaludis cells. Collectively, slowdown of protein synthesis in M. maripaludis was achieved by both a reduction in the number of working ribosomes and their elongation rate while total number of ribosomes remained invariant, rather than by a growth rate–dependent regulation of ribosome synthesis as in E. coli.

Fig. 5.

Ribosome activity. Polysome fraction (black diamonds) correlated logarithmically with dilution rate (y = 11.54 ln(x) + 76, R2 = 0.93, P value < 0.01), showing data from chemostat-grown cells (filled diamonds) and an exponential phase batch culture sample (open diamonds). Shaded areas depict 5% confidence level intervals.

Discussion

Our study of the methanogenic archaeon M. maripaludis under energy-limiting conditions revealed a physiological strategy for adjusting cellular resource allocation to different growth rates that is fundamentally different from that reported for E. coli. In E. coli, nearly half the proteome (by mass) is growth rate regulated, which includes an increase in transporters and catabolic pathways (tricarboxylic acid cycle) and a decrease in anabolic pathway enzymes (amino acid and nucleotide synthesis as well as ribosomes) at lower growth rates (13). Such preferential investing of limited resources in the expression of transporters and catabolic pathways at low growth rates has been postulated to provide a competitive advantage for E. coli for nutrient uptake and exploration of alternative energy sources in its niche (24, 54).

Instead of a closely regulated physiology to accommodate varying energy flux, M. maripaludis exhibits a “relaxed” phenotype by maintaining a relatively constant proteome allocation, cell morphology, and cellular composition. As an obligate methanogen, M. maripaludis is a metabolically highly specialized microbe that lacks any alternative catabolic pathway and is, therefore, “locked” into methanogenesis as the sole means of energy conservation. Thus, this microbe presumably does not benefit from extensive proteome reallocation in response to different growth rates. Indeed, both the methanogenesis pathway enzymes and the putative formate uptake protein FdhC (MMP1301, Dataset S2) were consistently expressed at a high level, and M. maripaludis did retain the capacity to rapidly resume a high methanogenesis rate following a nutrient upshift over a wide range of investigated growth rates (Fig. 3). The only significantly growth rate–regulated proteome sector was motility/chemotaxis (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The fact that motility and chemotaxis proteins (most notably components of the archaellum) were down-regulated during slow growth suggests that relative costs for motility are significant when the energy supply becomes more limiting. The M. maripaludis strategy does not require complex regulatory features that are commonly found in microbes selected for competition for fast growth (24). Changes in catabolic enzymatic activity as well as cell size seem to be induced only when nutrient flux is very low and below a certain threshold. The cause for a decrease of methanogenesis capacity despite a similar proteome landscape at very low growth rates is unclear. Possible hypotheses include a decrease in the metabolite pools during slow growth, posttranslational control of enzyme activities, or an increased fraction of intact-but-inactive cells. The lack of regulation as observed here for formate limitation does not indicate the absence of growth rate-dependent regulation under other conditions for M. maripaludis, such as electron acceptor limitation (55, 56) or phosphate, nitrogen, or carbon limitation (57). We argue that such a phenotype as discovered here is not a special case for M. maripaludis but may also exist in other metabolically specialized prokaryotes. For example, lactic acid bacteria do not closely regulate their catabolic and anabolic proteome, including ribosomal proteins, at different growth rates (58, 59), despite having alternative catabolic strategies as part of their metabolism.

Our systems-level study also revealed an increased flux of energy toward non-growth-related processes during slow growth, which led to lower yields (9). At faster growth, our observed maintenance energy was lower than that reported for M. maripaludis growing on H2/CO2 (60), yet higher than those estimated for Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina barkeri (61, 62). The relatively small differences in maintenance energy can be attributed to different growth conditions. Notably, in our study, the maintenance coefficient decreased at lower growth rates, indicating that M. maripaludis is able to lower its maintenance energy requirement at lower growth rates, possibly due to changes in physiological state as indicated by the lower methanogenesis capacity. This trend is consistent with observations that maintenance energy is not constant but depends on growth rate (11, 63, 64). Indeed, calculated maintenance energy requirement by microbes in natural settings where doubling times are in the order of years, such as subseafloor sediments, can be several orders of magnitude lower than those obtained under laboratory conditions (2, 25). Scavenging of lysed biomass by growing cells to lower the maintenance energy requirement is unlikely to contribute significantly, because cell debris cannot be catabolically metabolized by M. maripaludis and amino acid uptake is very limited.

A positive dependence of ribosome expression and growth rate as established in several bacterial species, including E. coli, yeast, and mammalian cells (13, 65), also does not hold true for M. maripaludis. In M. maripaludis, the slowdown of protein synthesis is achieved by engaging fewer ribosomes and by lowering elongation rates rather than by reducing ribosome numbers. Such an unregulated, “relaxed” phenotype has been observed in other methanogens (66) and a few other archaeal species (67–69). In line with this phenotype, the major ribosome regulator (p)ppGpp as well as its synthesis/hydrolysis enzymes identified in many bacteria are lacking in M. maripaludis and, more broadly, the domain Archaea (70). Some archaea have developed a (p)ppGpp-independent regulation of ribosome content under conditions of amino acid deprivation (67–69). Considering that ribosome synthesis is costly, the ecological benefit of maintaining a high number of unengaged ribosomes during slow growth is unclear. It is possible that it allows for a fast, and ultimately less costly, resumption of protein synthesis following a nutrient upshift, or it may represent a bet-hedging survival strategy to counteract molecule degradation.

The above findings raise the intriguing question of the “cost” of developing a complex regulatory network such as the one present in E. coli and its relationship to catabolic complexity. The dramatic growth rate-dependent changes observed in fast growing chemoheterotrophs like E. coli and other model microorganisms with high metabolic flexibility might be a particular adaptation to high-energy flux and highly fluctuating environments. Such a strategy might be advantageous for microorganisms that regularly encounter an excess of available energy substrate and have the ability to metabolize a variety of substrates. Our data suggest that microorganisms adapted to environmental niches with limited energy availability and narrow substrate range may pursue an alternative strategy. The ecological advantage for M. maripaludis to keeping a constant catabolic and anabolic proteome, irrespective of the change in energy flux, is intriguing. In salt marshes, its original habitat, M. maripaludis represents only a small fraction of the total methanogens, most of which are more slowly growing Methanomicrobiales spp. (71). The ability to swiftly switch to fast growth may enable it to respond to sudden inputs of substrates faster and outcompete other hydrogenotrophic methanogens.

Materials and Methods

Growth Conditions.

M. maripaludis strain MM901 [derivative of wild-type strain S2 (72)] was grown in two bioreactors (New Brunswick Scientific Bioflo 3000, Eppendorf Bioflo 120) operated as chemostats under anaerobic conditions with formate as the only electron donor supplied in limiting concentration of 200 mM in the glycylglycine-buffered reservoir medium (73): 200 mM glycylglycine, 200 mM sodium formate, 180 mM sodium chloride, 14 mM magnesium sulfate, 13.5 mM magnesium chloride, 9.3 mM ammonium chloride, 4.6 mM potassium chloride, 1.0 mM calcium chloride, 1 mM sodium sulfide, 0.8 mM potassium phosphate, 4.4 nM resazurin, 11 nM sodium selenite, 13.6 nM sodium tungstate, 1× trace element solution SL-10 (74), 1× vitamin solution DSMZ 141; pH was adjusted to 7.0 with potassium hydroxide. Culturing was performed at 30 °C under constant agitation (250 rpm). Reactors were inoculated with overnight cultures transferred once in batch culture from freshly thawed cryostocks. The headspace was set to accumulate 3 psi of overpressure that was released via one-way check valves. Fresh anoxic medium was continuously supplied from a 5 L reservoir bottle that was pressurized to 3 psi with 100% N2 gas and continuously stirred. All gas and medium connections and tubing consisted of materials that limit oxygen penetration by diffusion to a minimum (stainless steel, PEEK, Norprene, and Tygon). The culture volume was maintained at 750 mL with synchronized in- and out-flow peristaltic pumps. To constrain our study to reveal features of acclimation, and not genetic adaptation, to slow growth, we initiated each chemostat experiment from the same set of cryostocks and operated the reactors for at least four retention times which corresponds to almost six doubling times, which is sufficiently long for the system to reach steady state but not long enough to accumulate genetic variants. Dilution rates were selected to cover a range of 40% down to 1% of the maximum growth rate in batch culture (μmax), and biological triplicates were run at following dilution rates: 0.087 ± 0.003 (fast, F, 37% of μmax), 0.028 ± 0.001 (medium, M, 12% of μmax), 0.010 ± 0.001 h−1 (slow, S, 4% of μmax), and 0.003 ± 0.001 h−1 (very slow, XS, 1% of μmax) (Dataset S1). Growth in the reactors was monitored by measuring the optical density at an absorption of 600 nm (OD600) using a CO8000 cell density meter (WPA, Biochrom Ltd.). Formate concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography with an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad). Gas production was measured using a bubble flowmeter (Sigma Aldrich), and methane concentration in the outflow gas was measured using an 8610C gas chromatograph (SRI Instruments) as previously described (75).

Proteomics.

Samples for proteomic analysis were sampled in triplicates by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 3 min at 4 °C, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Mass spectrometry was performed using an Eksigent EKSPERT NanoLC 425 chromatography system, and proteins were quantified using spectral counting and relative quantification against a 15N-labeled reference (see SI Appendix for details regarding sample preparation, data acquisition, and data analysis). Values of technical triplicates were combined using the mean. In order to test for growth rate dependence of individual proteins and proteome sectors, a linear model was used in R to test for significant nonzero slopes. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction (76). Proteome sectors were defined on multiple levels based on functional annotation using RAST (77, 78) and manually curated (Dataset S2). The mass spectrometry proteomics data are available on PRIDE/ProteomeXchange (79) under the accession number PXD024262 and on MassIVE under accession number MSV000086844.

Maintenance Energy.

The maintenance coefficient was estimated by the slopes of the linear regression in a plot of the reciprocal values of growth yield (1/Y) against the reciprocal values of the dilution rate (1/D) (41). The nonlinear relationship indicating different maintenance energy requirements at different growth rates was approximated using biphasic linear regression. Relative maintenance energy was estimated by comparing the calculated maintenance energy values to the total amount of ATP available via formate based on conversion stoichiometry and assuming an ATP yield of 0.5 mol ATP per mol methane (36).

Estimation of Cell Lysis in Chemostat.

To estimate cell lysis, DNA and protein content inside and outside of cells in the reactors were measured by Qubit dsDNA HS assay (Invitrogen) and Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Cells were lysed by 0.01% SDS (80). For DNA measurement, to reduce unspecific reading from background, the samples were first treated with RNase A (New England Biolabs) at 30 °C for 30 min followed by Qubit assay and subsequently treated with DNase at 37 °C overnight and quantified by Qubit assay again. The DNA content of a sample was taken as the difference from the two assays. Longer incubation with RNase or DNase did not result in more degradation of RNA or DNA. To better infer the amount of lysis in the medium supernatant, a standard calibration was made by using M. maripaludis cultures at different cell densities and measuring DNA content in the lysate (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Further, to assess the effect of DNA degradation over time considering the retention time of lysate in the chemostats varies, anaerobic lysates incubated at 30 °C for more than 14 d were measured to mimic the slowest dilution rates. Surprisingly, less than 2% of DNA degradation was observed and considered neglectable. Finally, the cell lysis rate was estimated by assuming a constant rate and fitted to data obtained for different dilution rates (81, 82) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Methanogenesis Capacity.

To measure the methanogenesis capacity of cells, 5 mL aliquots were sampled from the chemostat and transferred to anoxic Hungate tubes containing 150 mM formate and 1 mM sodium sulfide. Pseudomonic acid (5 µg mL−1) was added to inhibit synthesis of new proteins. Methane formation was monitored by measuring the methane concentration in the headspace 2 to 3 times per hour for 6 h using an SRI 8610C gas chromatograph (SRI Instruments) and normalized against cell density (OD600).

Flow Cytometry.

Flow cytometry was performed on a BD Influx cell sorter (BD Biosciences) at the Stanford Shared FACS Facility, and flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10 software (FlowJo LLC). Cells were fixed by mixing culture 1:1 with 3% glutaraldehyde/3% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C over night, washed twice in 1× PBS and stored in a 1:1 1× PBS:100% ethanol solution. Samples were diluted in 1× Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer containing 0.25% Tween-20, 0.2 g L−1 RNase A and stained using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes). CountBright absolute counting beads (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) were added in order to determine cell counts. Nonfluorescent microspheres (Flow Cytometry Size Calibration Kit, Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) were used as a reference for size calibration of the forward scatter. DNA content/chromosome copy number was determined by calibrating picogreen fluorescence intensities against peaks corresponding to 1 and 2 copies of E. coli genomes, obtained by analyzing E. coli cells that were treated with rifampicin. Briefly, E. coli was grown in M9 medium with 2.0 g L−1 glucose aerobically and anaerobically to an OD600 of 0.08 and 0.16, respectively, and treated with 0.2 g L−1 rifampicin for 3 h.

Cell Size Determination by Microscopy.

Cell size was also determined microscopically using a method developed by ref. 83. Briefly, 1 µL of culture was placed onto a 1× PBS +2% agarose pad, allowed to air dry on the pad, and sealed with a coverslip. Cells were imaged on a Nikon TiE microscope using a 100× Ph3 objective (NA 1.45) with Andor iXon camera, and phase contrast images were collected (100 positions per sample, containing several thousand cells) using µManager version 1.4 (84). Cell size information was extracted by image analysis using the MATLAB package Morphometrics version 1.1 (83).

Total Protein Quantification.

Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Total RNA and rRNA Quantification.

Total RNA was isolated by phenol:chloroform method following protocols by ref. 85. Cells were lysed by 2% SDS. To account for RNA loss during phenol:chloroform phase separation steps, a known amount of luciferase control RNA (L4561, Promega) was spiked to samples right after lysis as internal control. DNA was removed from the samples by DNase treatment using RapidOut DNA removal kit (ThermoFisher). The total RNA samples were analyzed and quantified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer with the RNA 6000 Nano kit (Agilent). The rRNA fraction was quantified by integrating the area under 16S and 23S peak in the 2100 Expert software using the Prokaryote Total RNA Nano Assay (version 2.5) (57). Luciferase control RNA forms a distinct peak between two rRNA peaks (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Its area was used to correct for total RNA.

Quantification of Polysome Fractions.

Polysome profiling by sucrose gradient were carried out to quantify polysomes fractions. Cultures from chemostat or at exponential phase in batch culture were poured on ice to quickly chill and collected by centrifugation for 10 min at 8,000 × g. Cell pellets were resuspended with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl, 0.4% Triton X-100, 400 U/mL RNaseOUT, 2 mM DTT, 100 U/mL RNase-free DNase I) and were lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles. The cell lysates were quantified by NanoDrop and samples of 80 to 200 μg RNA concentration were loaded to 10 to 50% linear sucrose gradients (20 mM Tris⋅HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl, and 2 mM DTT) made by GradientMaster (BioComp). The gradients were centrifuged at 221,652 × g for 2 h at 4 °C. Gradients were fractionated by BioComp Gradient Fractionator, and the absorption curves at 254 nm were recorded by an ultraviolet monitor. For quantification, upper fractions containing 30S and 50S subunits, free 70S ribosomes, and monosomes were pooled and separated from lower fractions of polysomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). RNAs from different fractions were purified by phenol:chloroform extraction with luciferase control RNA spiked in as an internal standard to account for purification loss. The ribosomal RNA was quantified by Bioanalyzer as described above (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The polysome fraction was calculated by dividing the ribosomal RNA from the lower gradient fractions by the sum of ribosomal RNA from the whole gradient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Knapp and K. C. Hwang for assistance with microscopic measurements. We thank Ting-Ting Lee for assistance with the gradient maker and fractionator. We thank Terence Hwa for numerous insightful discussions. This work is supported by Grant OCE-0939564 from the NSF/University of Southern California, Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations, W911NF2010111 from the US Army Research Office, and Grant R35-GM136412 from the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2025854118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Proteomic mass spectrometry data data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange PRIDE database (PXD024262) and on MassIVE (MSV000086844). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Berghuis B. A., et al., Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in archaeal phylum Verstraetearchaeota reveals the shared ancestry of all methanogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 5037–5044 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley J. A., et al., Widespread energy limitation to life in global subseafloor sediments. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0697 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jørgensen B. B., Deep subseafloor microbial cells on physiological standby. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18193–18194 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boetius A., Anesio A. M., Deming J. W., Mikucki J. A., Rapp J. Z., Microbial ecology of the cryosphere: Sea ice and glacial habitats. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 677–690 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnabosco C., et al., The biomass and biodiversity of the continental subsurface. Nat. Geosci. (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Hondt S., Pockalny R., Fulfer V. M., Spivack A. J., Subseafloor life and its biogeochemical impacts. Nat. Commun. 10, 3519 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipp J. S., Morono Y., Inagaki F., Hinrichs K. U., Significant contribution of Archaea to extant biomass in marine subsurface sediments. Nature 454, 991–994 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valentine D. L., Adaptations to energy stress dictate the ecology and evolution of the Archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 316–323(2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roller B. R. K., Schmidt T. M., The physiology and ecological implications of efficient growth. ISME J. 9, 1481–1487 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoehler T. M., Jørgensen B. B., Microbial life under extreme energy limitation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 83–94 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Bodegom P., Microbial maintenance: A critical review on its quantification. Microb. Ecol. 53, 513–523 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basan M., et al., Overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli results from efficient proteome allocation. Nature 528, 99–104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui S., et al., Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals a simple strategy of global resource allocation in bacteria. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 784 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidi D., Milo R., Lessons on enzyme kinetics from quantitative proteomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 46, 81–89 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaechter M., MaalOe O., Kjeldgaard N. O., Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 19, 592–606 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomura M., Gourse R., Baughman G., Regulation of the synthesis of ribosomes and ribosomal components. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 75–117 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemp P. F., “Can we estimate bacterial growth rates from ribosomal RNA content?” in Molecular Ecology of Aquatic Microbes, Joint I., Ed. (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1995), pp. 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott M., Gunderson C. W., Mateescu E. M., Zhang Z., Hwa T., Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: Origins and consequences. Science 330, 1099–1102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai X., et al., Reduction of translating ribosomes enables Escherichia coli to maintain elongation rates during slow growth. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonenshein A. L., Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 917–927(2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postma E., Verduyn C., Scheffers W. A., Van Dijken J. P., Enzymic analysis of the crabtree effect in glucose-limited chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55, 468–477(1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huberts D. H. E. W., Niebel B., Heinemann M., A flux-sensing mechanism could regulate the switch between respiration and fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 12, 118–128 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basan M., et al., Inflating bacterial cells by increased protein synthesis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 836 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molenaar D., van Berlo R., de Ridder D., Teusink B., Shifts in growth strategies reflect tradeoffs in cellular economics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 323 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita R. Y., Bacteria in Oligotrophic Environments (Springer, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vadia S., Levin P. A., Growth rate and cell size: A re-examination of the growth law. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 24, 96–103(2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai X., Shen Z., Wang Y., Zhu M., Sinorhizobium meliloti, a slow-growing bacterium, exhibits growth rate dependence of cell size under nutrient limitation. MSphere 3, e00567-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fegatella F., Lim J., Kjelleberg S., Cavicchioli R., Implications of rRNA operon copy number and ribosome content in the marine oligotrophic ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 4433–4438 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia N. S., Bonachela J. A., Martiny A. C., Interactions between growth-dependent changes in cell size, nutrient supply and cellular elemental stoichiometry of marine Synechococcus. ISME J. 10, 2715–2724 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blazewicz S. J., Barnard R. L., Daly R. A., Firestone M. K., Evaluating rRNA as an indicator of microbial activity in environmental communities: Limitations and uses. ISME J. 7, 2061–2068 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binder B. J., Liu Y. C., Growth rate regulation of rRNA content of a marine synechococcus (Cyanobacterium) strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3346–3351 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worden A. Z., Binder B. J., Growth regulation of rRNA content in Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (Marine Cyanobacteria) measured by whole-cell hybridization of rRNA-targeted peptide nucleic acids. J. Phycol. 39, 527–534 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerkhof L., Kemp P., Small ribosomal RNA content in marine Proteobacteria during non-steady-state growth. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 30, 253–260 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odaa Y., Slagmana S., Meijerb W. G., Forneya L. J., Gottschala J. C., Influence of growth rate and starvation on fluorescent in situ hybridization of Rhodopseudomonas palustris. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32, 205–213 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schimel J., Balser T. C., Wallenstein M., Microbial stress-response physiology and its implications for ecosystem function. Ecology 88, 1386–1394 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thauer R. K., Kaster A. K., Seedorf H., Buckel W., Hedderich R., Methanogenic archaea: Ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitman W. B., Shieh J., Sohn S., Caras D. S., Premachandran U., Isolation and characterization of 22 mesophilic methanococci. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 7, 235–240 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haydock A. K., Porat I., Whitman W. B., Leigh J. A., Continuous culture of Methanococcus maripaludis under defined nutrient conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238, 85–91 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rittmann S., Seifert A., Herwig C., Quantitative analysis of media dilution rate effects on Methanothermobacter marburgensis grown in continuous culture on H 2 and CO 2. Biomass Bioenergy 36, 293–301 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones W. J., Paynter M. J. B., Gupta R., Characterization of Methanococcus maripaludis sp. nov., a new methanogen isolated from salt marsh sediment. Arch. Microbiol. 135, 91–97 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirt S. J., The maintenance energy of bacteria in growing cultures. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 163, 224–231 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hildenbrand C., Stock T., Lange C., Rother M., Soppa J., Genome copy numbers and gene conversion in methanogenic archaea. J. Bacteriol. 193, 734–743 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ercan O., et al., Physiological and transcriptional responses of different industrial microbes at near-zero specific growth rates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 5662–5670(2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boylen C. W., Pate J. L., Fine structure of Arthrobacter crystallopoietes during long-term starvation of rod and spherical stage cells. Can. J. Microbiol. 19, 1–5 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boylen C. W., Mulks M. H., The survival of coryneform bacteria during periods of prolonged nutrient starvation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 105, 323–334 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kefford B., Humphrey B. A., Marshall K. C., Adhesion: A possible survival strategy for leptospires under starvation conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 13, 247–250 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnstone B., Jones R., Physiological effects of long-term energy-source deprivation on the survival of a marine chemolithotrophic ammonium-oxidizing bacterium. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 49, 295–303 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crist D. K., Wyza R. E., Mills K. K., Bauer W. D., Evans W. R., Preservation of Rhizobium viability and symbiotic infectivity by suspension in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47, 895–900 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindås A. C., Bernander R., The cell cycle of archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 627–638 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campos M., et al., A constant size extension drives bacterial cell size homeostasis. Cell 159, 1433–1446 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mechold U., Malke H., Characterization of the stringent and relaxed responses of Streptococcus equisimilis. J. Bacteriol. 179, 2658–2667 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassels R., Oliva B., Knowles D., Occurrence of the regulatory nucleotides ppGpp and pppGpp following induction of the stringent response in staphylococci. J. Bacteriol. 177, 5161–5165 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes J., Mellows G., Inhibition of isoleucyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase in Escherichia coli by pseudomonic acid. Biochem. J. 176, 305–318 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Böhme H., Schrautemeier B., Comparative characterization of ferredoxins from heterocysts and vegetative cells of Anabaena variabilis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 891, 1–7 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roslev P., King G. M., Survival and recovery of methanotrophic bacteria starved under oxic and anoxic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 2602–2608 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kracke F., Deutzmann J. S., Gu W., Spormann A. M., In situ electrochemical H2 production for efficient and stable power-to-gas electromethanogenesis. Green Chem. 22, 6194–6203 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li S. H. J., et al., Escherichia coli translation strategies differ across carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus limitation conditions. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 939–947 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goel A., et al., Protein costs do not explain evolution of metabolic strategies and regulation of ribosomal content: Does protein investment explain an anaerobic bacterial crabtree effect? Mol. Microbiol. 97, 77–92 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goffin P., et al., Understanding the physiology of Lactobacillus plantarum at zero growth. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 413(2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richards M. A., et al., Exploring hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis: A genome scale metabolic reconstruction of Methanococcus maripaludis. J. Bacteriol. 198, 3379–3390 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benedict M. N., Gonnerman M. C., Metcalf W. W., Price N. D., Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and hypothesis testing in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A. J. Bacteriol. 194, 855–865 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feist A. M., Scholten J. C. M., Palsson B. Ø., Brockman F. J., Ideker T., Modeling methanogenesis with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of Methanosarcina barkeri. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 0004 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chesbro W., Evans T., Eifert R., Very slow growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 139, 625–638 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tempest D. W., Neijssel O. M., The status of YATP and maintenance energy as biologically interpretable phenomena. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 38, 459–486 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dai X., Zhu M., Coupling of ribosome synthesis and translational capacity with cell growth. Trends Biochem. Sci. 45, 681–692 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beauclerk A. A., Hummel H., Holmes D. J., Böck A., Cundliffe E., Studies of the GTPase domain of archaebacterial ribosomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 151, 245–255 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cellini A., et al., Stringent control in the archaeal genus Sulfolobus. Res. Microbiol. 155, 98–104 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cimmino C., Scoarughi G. L., Donini P., Stringency and relaxation among the Halobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 175, 6659–6662 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DiRuggiero J., Achenbach L. A., Brown S. H., Kelly R. M., Robb F. T., Regulation of ribosomal RNA transcription by growth rate of the hyperthermophilic Archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 111, 159–164 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Atkinson G. C., Tenson T., Hauryliuk V., The RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) superfamily: Distribution and functional evolution of ppGpp synthetases and hydrolases across the tree of life. PLoS One 6, e23479 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Franklin M. J., Wiebe W. J., Whitman W. B., Populations of methanogenic bacteria in a Georgia salt marsh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54, 1151–1157 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Costa K. C., et al., Protein complexing in a methanogen suggests electron bifurcation and electron delivery from formate to heterodisulfide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11050–11055 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Long F., Wang L., Lupa B., Whitman W. B., A flexible system for cultivation of Methanococcus and other formate-utilizing methanogens. Archaea 2017, 7046026 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Widdel F., Kohring G.-W., Mayer F., Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. Arch. Microbiol. 129, 395–400 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lohner S. T., Deutzmann J. S., Logan B. E., Leigh J., Spormann A. M., Hydrogenase-independent uptake and metabolism of electrons by the archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. ISME J. 8, 1673–1681 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aziz R. K., et al., The RAST server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9, 75 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Overbeek R., et al., The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D206–D214(2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perez-Riverol Y., et al., The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D442–D450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones J. B., Bowers B., Stadtman T. C., Methanococcus vannielii: Ultrastructure and sensitivity to detergents and antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 130, 1357–1363 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pirt S. J., Principles of Microbe and Cell Cultivation (Wiley, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rittmann B. E., McCarty P. L., Environmental biotechnology : Principles and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 7, 357–365(2001). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ursell T., et al., Rapid, precise quantification of bacterial cellular dimensions across a genomic-scale knockout library. BMC Biol. 15, 17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Edelstein A. D., et al., Advanced methods of microscope control using μManager software. J. Biol. Methods 1, e10 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Griffiths R. I., Whiteley A. S., O’Donnell A. G., Bailey M. J., Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5488–5491 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Proteomic mass spectrometry data data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange PRIDE database (PXD024262) and on MassIVE (MSV000086844). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.