Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a massive shift toward virtual living, with video-conferencing now a primary means of communication for both work and social events. Individuals are finding themselves staring at their own video reflection, often for hours a day, scrutinizing a distorted image on screen and developing a negative self-perception. This survey study of over 100 board-certified dermatologists across the country elucidates a new problem of Zoom dysmorphia, where patients seek cosmetic procedures to improve their distorted appearance on video-conferencing calls.

Keywords: Esthetics, Body dysmorphia, Cosmetic dermatology, Self-perception

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaped a culture in which many individuals now work and socialize entirely from home. At the start of quarantine, a Gallup survey reported that nearly 62% of employed Americans were working from home, with the majority of survey participants preferring to continue working from home even when conditions improve (Brenan, 2020). Globally, the remote workforce was already on the rise, increasing 140% from 2005 to 2019, and that number has accelerated even further since the start of the pandemic (Scott, 2020).

Video-conferencing is now the primary tool for social events, with Zoom weddings, happy hours, and even funerals. Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts, and other similar programs have allowed life, collaboration, and productivity to proceed virtually, but these platforms (herein collectively referred to as “Zoom”) may also be affecting the way people view themselves. Now forced to confront their image on video sometimes for hours each day, people are becoming more aware of how they appear to others and may be unsettled by what they see. Even more unsettling is that, due to the intrinsic properties of the technology being used, the image is somewhat distorted (Ward et al., 2018).

Before Zoom, a slew of photo-editing apps allowed individuals to smoothen their skin, narrow their nose, and enlarge their eyes to create a filtered version of themselves as the goal they wish to achieve. Patients brought edited selfies to their esthetic physicians, requesting edits to their appearance sometimes beyond the scope of even advanced plastic surgery (Özgür et al., 2017). This phenomenon, referred to as Snapchat dysmorphia, has caused widespread concern for its potential to trigger or worsen body dysmorphic disorder (BDD; Rajanala et al., 2018). Unlike Snapchat, where people knowingly change their appearance, in what we have deemed Zoom dysmorphia (Rice et al., 2020) BDD may be triggered by prolonged staring and self-reflection upon an unknowingly distorted image (i.e., aspects of the technological interface and front-facing cameras in video-conferencing can distort facial proportions, causing or worsening perception of problems in one’s own appearance). We set out to investigate the esthetic provider’s perspective of this emerging issue of whether frequent video-conferencing may be contributing to an increase in BDD and subsequent cosmetic consultations.

Methods

In this institutional review board–exempted study, providers in dermatology throughout the country and in diverse practice settings were queried with regard to relative changes in cosmetic consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether use of video-conferencing has been cited by their patients as a reason to seek care. Survey development began with qualitative interviews of physicians managing cosmetic concerns, representing various backgrounds and practice settings, to identify relevant questions. The survey was reviewed for content and face validity by a statistician. A voluntary anonymous survey was made available to the membership of the Women’s Dermatologic Society following review by the organization’s Academic Dermatology Committee. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted by Lifespan's Department of Information Services.

Results

A total of 134 participants responded to the survey. Demographic information is listed in Table 1. Among the participants, 110 (82%) were board-certified dermatologists, and the remaining were dermatology residents (12.7%) or advanced care practitioners in dermatology (5.3%). A total of 76 providers (56.7%) reported a relative increase in patients seeking cosmetic consultations compared with prior to the pandemic, and 114 providers (86.4%) noted their patients citing video-conferencing calls as a reason to seek care.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 18–24 | 2 (1.5) | |

| 25–34 | 44 (32.8) | |

| 35–44 | 56 (41.8) | |

| 45–54 | 14 (10.4) | |

| 55–64 | 18 (13.4) | |

| 65–74 | 0 (0) | |

| >75 | 0 (0) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 (14.9) | |

| Female | 114 (85.1) | |

| Nonbinary | 0 (0) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 22 (16.7) | |

| Black or African American | 14 (10.6) | |

| White | 82 (62.1) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (2.3) | |

| Other | 17 (12.9) | |

| Profession | ||

| Board-certified dermatologist | 110 (82.1) | |

| Dermatology resident | 17 (12.7) | |

| Dermatology physician assistant | 4 (3.0) | |

| Dermatology nurse practitioner | 1 (0.7) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5) | |

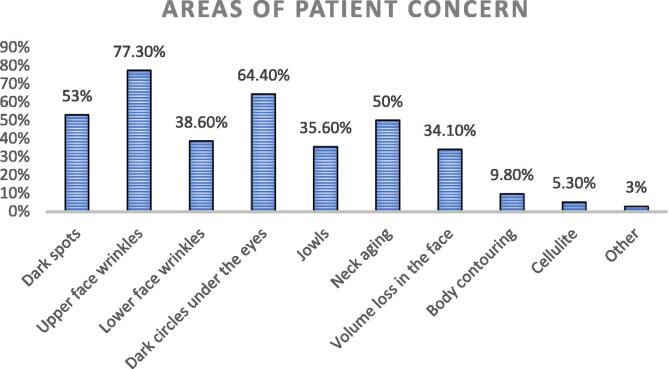

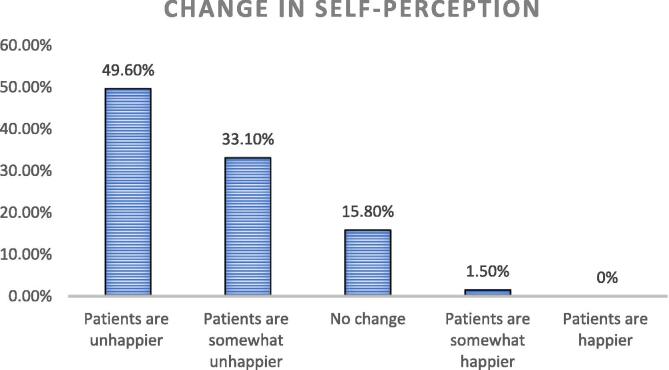

Regarding specific areas of the body, 80% of providers reported that patients focused on the forehead/glabellar regions and 78% reported focus on periocular areas. More specifically, 77% of providers reported patient cosmetic concerns about upper-face wrinkles, 64.4% for dark circles under the eyes, 53% for facial dark spots, and 50% for neck sagging. When asked about the most requested cosmetic procedures since the pandemic began, 94% of providers selected neuromodulators, such as Botox (botulinum toxin A), 82.3% selected injectable dermal fillers, and 65.4% selected laser treatments. Lastly, 110 providers (82.7%) marked their patients as either being somewhat more or significantly more unhappy with their appearance since using video-conferencing during the pandemic.

Discussion

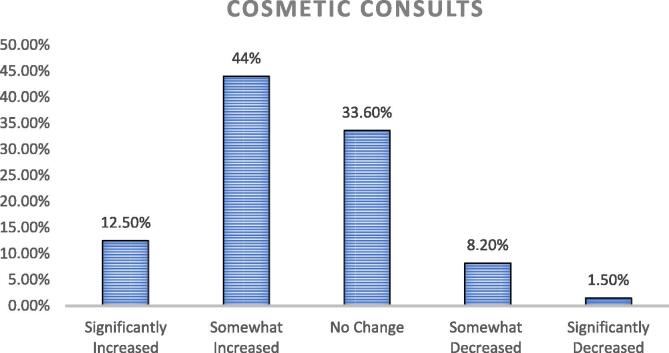

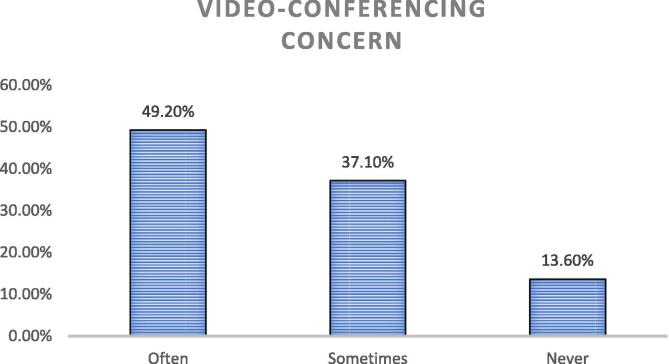

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic limiting in-person office visits and stalling many elective procedures, dermatology cosmetic consultations are on the rise relative to pre-pandemic times. With people now spending record amounts of time on virtual platforms seeing their virtual image, they are becoming more critical of their features and inquiring about cosmetic improvements. In this survey study of >100 board-certified dermatologists from across the country, >50% indicated a relative increase in cosmetic consultations within their practices despite the state of the pandemic (Fig. 1). Even more notable is that 86% of respondents reported that their patients are referencing video-conferencing as a reason for their new cosmetic concerns (Fig. 2). Other studies have noted similar results, with one recent survey of the general public showing that of those who previously did not have an interest in facial cosmetic treatments, 40% now plan to pursue treatments based on concerns from their video-conferencing appearance alone (Cristel et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Cosmetic consults. Providers were asked to indicate the change in cosmetic consults relative to pre-pandemic times.

Fig. 2.

Citing Zoom. Providers were asked how often their patients cite their appearance on video-conferencing calls as a reason to seek care.

According to the surveyed dermatologists, neuromodulating agents (e.g., Botox and Dysport), filler injections, and laser treatments were noted as the most frequently requested cosmetic procedures reaching their offices. In a time where more invasive esthetic surgical procedures are restricted for concern of unnecessary virus spread, a higher interest in minimally invasive procedures is expected. Patients appear to be the most concerned with regions from the neck up, most notably the forehead/glabella, eyes, neck, and hair. Specific concerns include upper-face wrinkles, circles/bags under the eyes, dark spots, and neck sagging (Fig. 3). Concerns below the neck were much less frequently reported, with body contouring and cellulite treatments noted to be on the rise by <10% of the surveyed dermatologists. Interestingly, an analysis of Google search trends during the COVID-19 pandemic showed an increase in search terms such as “acne” and “hair loss” (Kutlu, 2020). The authors of that analysis attributed the search trend to the association of acne and hair loss with anxiety and depression, psychological conditions weighing heavily on many quarantined individuals. Numerous other factors may also play a role, such as mask occlusion causing acne mechanica, as well as the association of telogen effluvium with COVID-19 infection (Miyazato et al., 2020). Our results show the trend may also be due to the fact that people are now becoming more aware of their appearance, scrutinizing their features from the neck up as they see their video reflection daily.

Fig. 3.

Areas of patient concern as noted by dermatologists.

Of concern to providers is that patients are requesting more procedures as a result of increased video-conferencing, which has been shown in the literature to reflect a distorted facial appearance. This is causing concern for aspects of appearance that may not truly require correction or correction to the extent that the patient fears. Of even greater concern is the mental health aspect that is uncovered in this study, with 82.7% of surveyed providers reporting that their patients felt more displeased with their appearance now than ever before (Fig. 4). The psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been understandably negative, but why are patients so unhappy particularly with their appearance on Zoom?

Fig. 4.

Self-perception. Dermatologists were asked how their patients' self-perceptions had changed with the increased use of video-conferencing during the pandemic.

Studies have shown that those with higher levels of engagement on social media have higher levels of body dissatisfaction and depression (Shome et al., 2020, Woods and Scott, 2016). For example, one study showed that when instructed to upload photos to social media, most participants noted a decrease in self-confidence and an increase in desire to undergo cosmetic surgery (Shome et al., 2020). Although Zoom may not be considered social media, it does necessitate that people expose themselves in a virtual manner to which many are unaccustomed. Zoom adds an additional level of complexity by displaying one’s emotions in real time, leading users to watch themselves speak and react to others, which may cause a person to notice expression lines and wrinkles they are not used to seeing while looking in the mirror. Additionally, one’s reflection is displayed side by side to other members of the call, allowing for easy comparison and self-judgment.

The distorting effects of webcams could also contribute to the observed trend in cosmetic consultations, as patients remain unaware of how cameras can distort and degrade video quality and inaccurately represent one’s true appearance. For instance, camera angle and focal distance make a difference in the image that appears on screen. A 2018 study found that a portrait taken from 12 inches away increases perceived nose size by approximately 30% when compared with an image taken at 5 feet (Ward et al., 2018). With webcams often recording at shorter focal lengths, the result is an overall more rounded face, wider set eyes, broader nose, taller forehead, and disappearing ears obscured by cheeks (Třebický et al., 2016). Moreover, video calls condense life into a 2-dimensional image, leading a graded shadow along a curved surface, such as the nose, to appear as a flat, darkened area instead (Lu and Bartlett, 2014). This illusion may exacerbate the appearance of facial dark spots and bring unnecessary concern to users.

Combining these elements with the current trends in cosmetic consultations, it is apparent that Zoom, although a useful and necessary tool for maintaining productivity during quarantine, has introduced individuals to an unfamiliar virtual environment. This increased self-exposure and distorted image on screen may lead patients to develop thoughts of BDD, with a tendency to be preoccupied with real or imagined physical defects and causing functional impairment. These patients often seek cosmetic procedures to improve their perceived appearance, yet are rarely satisfied with the results, ending up in a cycle of self-dissatisfaction. Approximately 9% to 14% of patients in general dermatology clinics have a diagnosis of BDD, and within the cosmetic surgery setting, the prevalence is thought to be even higher (Vashi, 2016). With the number of patients with anxiety disorders increasing due to factors related to the pandemic, BDD is an important consideration in patient evaluations. Elucidating the limitations of webcams and examining the trends of this new virtual world, we can better serve patients by screening for such dysmorphic thoughts and connecting patients with appropriate counseling. Prior to the pandemic, patients presented to their esthetic physicians hoping to look more like their filtered Snapchat selfies; we have now entered an era in which people are forced to confront a distorted and often unflattering rendition of themselves for hours a day on Zoom and the distorted reflection promoting the phenomenon of Zoom dysmorphia.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a massive shift toward virtual living, with video-conferencing as a primary means of communication in all aspects of life. This survey study of >100 board-certified dermatologists across the country elucidates a new problem of Zoom dysmorphia, where patients seek cosmetic procedures to improve their appearance on video-conferencing calls. The study also highlights that patients may be staring for hours and scrutinizing a distorted image of themselves on screen and develop a negative self-perception as a result. Esthetic physicians and the medical community at large should be aware of this trend and be prepared to address Zoom dysmorphia, a potential emerging contributor to BDD, in patients seeking an esthetic evaluation so that we may better serve our patients as a whole.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study approval

The author(s) confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

References

- Brenan M. U.S. workers discovering affinity for remote work [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 July 16]. Available from: https://news. gallup. com/poll/306695/workers-discoveringaffinity-remote-work. aspx.

- Cristel R.T., Demesh D., Dayan S.H. Video conferencing impact on facial appearance: Looking beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020;22(4):238–239. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu Ö. Analysis of dermatologic conditions in Turkey and Italy by using Google Trends analysis in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6) doi: 10.1111/dth.13949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S.M., Bartlett S.P. On facial asymmetry and self-perception. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(6):873e–881e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazato Y., Morioka S., Tsuzuki S. Prolonged and Late-Onset Symptoms of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(11):ofaa507. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa507. Published 2020 Oct 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özgür E., Muluk N., Cingi C. Is selfie a new cause of increasing rhinoplasties? Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33(4):423–427. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajanala S., Maymone M.B.C., Vashi N.A. Selfies—living in the era of filtered photographs. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(6):443–444. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice S.M., Graber E., Kourosh A.S. A pandemic of dysmorphia: “Zooming” into the perception of our appearance. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020;22(6):401–402. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. Must have video conferencing statistics 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 July 28]. Available from: www.uctoday.com/collaboration/video-conferencing/video-conferencing-statistics/.

- Shome D., Vadera S., Male S.R., Kapoor R. Does taking selfies lead to increased desire to undergo cosmetic surgery. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(8):2025–2032. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Třebický V., Fialová J., Kleisner K., Havlíček J., Brañas-Garza P. Focal length affects depicted shape and perception of facial images. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashi N.A. Obsession with perfection: body dysmorphia. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(6):788–791. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B., Ward M., Fried O., Paskhover B. Nasal distortion in short-distance photographs: the selfie effect. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(4):333–335. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods H.C., Scott H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2016;51:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]