Abstract

Introduction:

Immigrants continue to face significant challenges in accessing primary healthcare (PHC) that often negatively impact their health. The present research aims to capture the perspectives of immigrants to identify potential approaches to enhance PHC access for this group.

Methods:

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted among a sample of first-generation Bangladeshi immigrants who had experience with PHC in Canada. A total of 13 FGDs (7 among women, 6 among men) were conducted with 80 participants (women = 42, men = 38) in their preferred language, Bangla. We collected demographic information prior to each focus group and used descriptive statistics to identify the socio-demographic characteristics of participants. We applied thematic analysis to examine qualitative data to generate a list of themes of possible approaches to improve PHC access.

Results:

The focus group findings identified different levels of approaches to improve PHC access: individual-, community-, service provider-, and policy-level. Individual-level approaches included increased self-awareness of health and wellness and personal knowledge of cultural differences in healthcare services and improved communication skills. At the community level, supports for community members to access care included health education workshops, information sessions, and different support programs (eg, carpool services for senior members). Suggested service-level approaches included providers taking necessary steps to ensure an effective doctor-patient relationship with immigrants (eg, strategies to promote cultural competencies, hiring multicultural staff). FGD participants also raised the importance of government- or policy-level solutions to ensure high quality of care (eg, increased after-hour clinics and lab/diagnostic services).

Conclusions:

Although barriers to immigrants accessing healthcare are well documented in the literature, solutions to address them are under-researched. To improve healthcare access, physicians, community health centers, local health agencies, and public health units should collaborate with members of immigrant communities to identify appropriate interventions.

Keywords: immigrant, access to care, community, solution, challenge, community engagement, integrated knowledge translation, participatory

Introduction

Optimal access to primary healthcare (PHC), which provides first-contact services along with continued and integrated healthcare for patients, has been well documented to reduce health inequalities in immigrant populations.1 However, using primary care has been consistently lower in immigrant populations compared to native born individuals.2 Healthcare systems and care providers face significant challenges in developing and implementing appropriate and relevant healthcare interventions to overcome barriers to optimum PHC access for immigrants. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of issues regarding access to PHC by immigrants in terms of identifying probable mitigation strategies is essential.

Published reports in Canada indicate that immigrants have unmet health needs, face considerable barriers to accessing primary health services, and perceive poorer quality and continuity of care.3-5 While some research has been undertaken on identifying barriers faced by immigrants while accessing healthcare in Canada,6 research around framing the barriers to identify appropriate solutions is limited. Additionally, a community participation approach to local health and sustainable development—a process through which community participation guides the assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation of health problems and solutions—is lacking within healthcare access research in immigrant populations.7 Unfortunately, meaningful active involvement of the immigrant community in conducting, governing, and priority setting in research and knowledge translation or mobilization has not been prioritized. There seems to be a lack of emphasis on taking a community-centered approach while seeking solutions, with a top-down approach appearing to have been adopted more frequently by the service delivery system. The objective of this study is to capture the perspectives of immigrants in identifying potential approaches to improving their access to PHC.

Methods

Community Engagement and Citizen Researcher Involvement

Adopting a solution-oriented approach toward complex multi-dimensional issues like access to primary care warrants meaningful engagement with grassroots communities, which will ensure the community is a partner in efforts to overcome barriers. Our program of research has encompassed the concepts of community-based participatory research (CBPR)8 and community-engaged integrated knowledge translation (iKT).9 In the community engagement phase, we conducted a number of informal conversations with Bangladeshi-Canadian community members, raising the research question we are investigating. We also had Bangladeshi-Canadian community-based citizen researchers as members of our research team (NR, AR, and ML), who have been instrumental in community engagement, participant recruitment, and the transcription and translation process related to our study activities. They were also closely engaged during the analysis process to contextualize the codes and themes arising from the focus group discussions (FGDs) and in writing the manuscript. We also discussed the study codes and themes during our paper-writing phase with 3 FGD participants who agreed to be contacted for this purpose.

Participant Recruitment

The FGD participants were adult first-generation legal Bangladeshi immigrants who have experience accessing Canadian PHC. Based on the distribution of Bangladeshi immigrants in Calgary, which we learned about from our discussion with community champions and citizen researchers, the following outreach strategies were employed for recruitment:

We distributed English and Bangla posters in community locations, including ethnic grocery stores, ethnic restaurants, and community centers.

We also employed a snowball recruitment method in which key grassroots community influencers were identified and contacted for their support in recruiting potential participants.

As people were enrolled for the FGDs, they were requested, as part of our snowballing, to engage with additional contacts based on their personal social networks.

Study posters were emailed through the Bangladeshi immigrant community socio-cultural organization email lists.

Advertisements were posted in the local Bangla newspaper.

A social media campaign was undertaken through Facebook and Twitter.

Potential participants were informed about the study objective, either by telephone or mail (first contact) or in-person (on-site). Participants were advised that participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any time before data analysis commenced. They were assured that any identifying data would be anonymous. The demographic details of the participants are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Participants.

| Variable | Men |

Women |

|---|---|---|

| (N = 38) | (N = 42) | |

| Age | ||

| <25 | 0 | 9 |

| 26-35 | 3 | 18 |

| 36-45 | 8 | 10 |

| 46-55 | 17 | 5 |

| 56-65 | 7 | 0 |

| >66 | 3 | 0 |

| Level of education | ||

| None | 0 | 0 |

| <High school | 0 | 1 |

| High school | 0 | 2 |

| >High school | 1 | 7 |

| University | 37 | 32 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 15 | 16 |

| Part time | 4 | 13 |

| Retired | 3 | 1 |

| Homemaker | 0 | 9 |

| Self-employed | 12 | 2 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 35 | 41 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | 32 | 41 |

| Hindu | 6 | 0 |

| Christian | 0 | 1 |

| Buddhist | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Length of time in Canada | ||

| <5 years | 6 | 5 |

| 5-9 years | 11 | 6 |

| 10-19 years | 12 | 24 |

| >20 years | 9 | 7 |

| Language spoken at home | ||

| Bangla | 37 | 41 |

| English | 1 | 1 |

| French | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 0 | 0 |

Conducting Focus Group Discussions

We conducted FGDs10,11 to explore the perceptions of immigrant men and women of Bangladeshi ancestry regarding the probable solutions for access issues to PHC in Canada. An FGD is an effective qualitative data collection method in the field of health disparities research among minority populations,12 as it allows participants to provide detailed information about complex experiences and the rationale behind their beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, and actions.13 We conducted a total of thirteen FGDs (7 among women, 6 among men), with 78 participants (40 women, 38 men) in their preferred language, Bangla. The FGDs were conducted in community venues for the convenience and accessibility of participants. This study was oriented within the conceptual model focusing on the structure, organization, and performance of primary care developed by Hogg et al14 Acknowledging the broader dimensions of macro- and micro-efficiency and healthcare system design, policy, and context is important to understand the complexity of primary care delivery. Indeed, this framework provides an excellent combination of the structural (healthcare system, practice context, organization of practice) and performance (healthcare service delivery, technical quality of clinical care) aspects of primary care. Studies have established structural factors that limit the use of PHC by immigrant communities.14 This study was reviewed and approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary prior to commencing any research activity.

FGDs were overseen by a moderator and an assistant moderator, both of whom were bilingual and fluent in both English and Bangla. The FGDs were conducted in Bangla, but the participants were given the option of using either Bangla or English. Each FGD started by the moderator explaining, and the participants signing, the written consent form. The moderator was responsible for applying appropriate working group techniques and was required to provide equal opportunities for communication to all participants. The moderator did not act as an expert but stimulated and supported discussions.

The moderator occasionally posed open-ended questions to clarify content or context, to deepen the perspectives voiced, and to stimulate the flow of discussion if participants’ statements were unclear or if the discussion came to a halt. The assistant moderator acted as a notetaker and was responsible for capturing what was expressed, noting the tone of the discussion and the order in which people spoke (by participant number or name), phrases or statements made by each participant, and non-verbal expressions. At the end of each discussion, the assistant moderator summarized the discussion and asked for feedback from the participants. FGDs were audio-recorded and lasted approximately 1.5 to 2 h.

Analysis

We undertook data analysis using the 6 phases of thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke,15 which include the following:

Familiarizing yourself with your data: All of the recorded FGDs were transcribed verbatim, and the complete transcript was compared with the recorded audio and the handwritten notes taken by the notetaker to fill in the gaps. The transcript was read multiple times searching for meanings and patterns to code.

Generating initial codes: The data from the first 3 FGDs were coded independently in English by 2 bilingual researchers (the Research Assistant [RA] and Principal Investigator [PI]) and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The remaining FGDs were coded by the RA and randomly checked by the PI. The 2 coders took the necessary steps to ensure the accuracy of the translation.11-13

Searching for themes: Thematic analysis was designed to identify the structural nature of qualitative data. An important step in thematic analysis is organizing texts and codes to reflect structural conditions, and we applied the Social Ecological Model16 for this purpose. At this stage, codes were extracted into Excel files (1 file per interview). After analyzing the codes, we collected the relevant codes into potential themes and gathered all data relevant to each potential theme.

Reviewing themes: At this stage, we tested the themes in relation to the coded extracts and entire data set and generated a thematic map of the analysis.

Defining and naming themes: At this stage of the ongoing analysis, we refined the specifics of each theme to reveal the overall story reflected and generated clear definitions and names for each theme.

Producing the report: After selecting vivid and compelling extract examples, we undertook a final analysis of selected extracts to tie the analysis to the research question and literature to produce a scholarly report of the analysis.

Results

Participant Profile

As shown in Table 1, the participants were predominantly educated, aged 26 to 45 years, and married. Most of the participants were employed either full time or part time. The majority of the participants migrated to Canada 10 to 19 years ago.

Proposed Solutions Framed within the Socio-Ecological Model

The various levels at which approaches for proposed solutions could be undertaken to improve immigrant PHC access are described below. These include: (1) individual-level approaches, (2) community-level approaches, (3) service provider-level approaches, and (4) policy-level approaches.

Individual-level approaches

FGD participants recognized that increased self-awareness of health and wellness and personal knowledge of cultural differences in healthcare services, as well as improved communication skills at the individual level, could play an important role in enhancing care access for immigrants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Solution Theme: Individual-Level Approaches Voiced by Focus Group Discussion Participants.

| Theme: Individual-level Approaches | |

|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

| Self-awareness of health and well-being | “Many of us may feel shy to talk about our body or illness. This shyness is in our culture, our religion. But to a doctor, a body is a body. . .many of us say we don’t want to see a male doctor, we only want to see a female doctor. But if these views don’t change, we will not get proper treatment. I should not say that I will take my pregnant wife to a male doctor. A doctor is a doctor, a patient is a patient. We won’t get proper access to care unless we change our behavior. . .this can happen if we improve our self-awareness, our consciousness.” (FG-01, Participant 4) |

| “Those who are in those positions (in healthcare), they need to develop self-awareness to recognize patient’s perspective, to respect patient’s beliefs and views. . .also patients need to understand the limitations of the doctors and help them to understand patients’ perspectives” (FG-01, Participant 3) | |

| Improving communication skills | “Language is a huge barrier; accent is a huge barrier. . .I write notes of my problems and take it to the doctor. My doctor draw pictures and explain me my problem. Tells me this is what your problem is, this is where you have problem, Now I understand better.” (FG-02, Participant 1) |

Self-awareness of health and well-being

FGD participants discussed the significance of self-awareness of health and well-being among immigrants. Being self-aware about available services and resources could help individuals take responsibility for their own health, to some extent, and help change personal beliefs and views.

FGD participants also expressed the need for improved self-awareness of healthcare providers, which would permit clinicians to understand the needs and subjective experience of patients better.

Improving communication skills

Language barriers pose challenges in accessing care for many immigrants. FGD participants discussed that improving their communication skills could be helpful in accessing care.

Community-level approaches

FGD discussions revealed the importance of community participation in improving care access. Community organizations could arrange health education programs, prepare brochures on health information in different languages, and organize support programs to improve access to care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Solution Theme: Community-Level Approaches Voiced by Focus Group Discussion Participants.

| Theme: Community-level Approaches | |

|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

| Community-based health information workshops | “Community organizations can play a vital role. . .they can host some kind of health programs. That can help us to be aware of different health conditions. . .and information sessions, for example, many of us don’t know about S**** C*** C*** and how to access their service. Community organizations can host such information sessions. They can provide us with information on primary care, the location of those facilities, phone number. . .they can play a vital role here” (FG-03, Participant 6) |

| “There is definitely a gap between the service that the newcomer centers provide and what we need. How many of us as newcomers can get useful information from the newcomer centers in Alberta? I went there once I moved here, but what information did I get? Nothing, nothing helpful, I don’t know what I received from them. I had to explore myself for everything. The community association that we have in our community don’t do anything other than musical events, dance or cultural events and picnics. Newcomers need more. . .such as information on job, health insurance, how health insurance works, how a low-income gets insurance. What about senior’s insurance” (FG-01, Participant 3) | |

| “The community organizations can prepare brochures or print leaflets on different health issues, for example, on dental healthcare, eye care etc. and then you can distribute to the community members when a large number people gather at different cultural community events” (FG-04, Participant 6) | |

| “I want to talk about “X” community. They organize English Language program. . .those who are locally graduated, they are helping out others who have language barriers, they are translating the medical terminologies to their languages. . .helping at different places, like at hospitals, and clinics. . .our community members can do that” (FG-04, Participant 1) | |

| “We can have an information booth at the community. As an individual, we can’t help lot, but if there is an information booth or center at the community that provides information on issues, like job, health insurance, how does it work. . .how parents get insurance once they come here as sponsored by us, that will help all the community members” (FG-01, Participant 3) | |

| Community-based interpreter services | “Community organizations can identify volunteers from the community who are interested to provide interpretation service. They can reach out to the volunteers and ask if they are interested and can do interpreter services” (FG-01, Participant 1) |

| “Community organizations can contact students from universities, schools. . .they can ask if anyone is interested to serve as a volunteer interpreter and they can inform that this clinic or that clinic needs interpreter services” (FG-06, Participant 7) | |

| Community support programs | “Community members or volunteers can offer support, for example, help seniors to make appointments online with their healthcare providers. Many elderly don’t know how to make appointments online, they don’t know how to check wait time. . .we can offer hospital ride, we can offer emotional support to the family members of sick person, can cook food for sick people” (FG-08, Participant 2) |

| Using social media | “There are community organizations in different communities, for example, we have Bangladesh Association, Kolkata Association, Marwari Association, Punjabi Association. There are lots of associations. . .why not each community association post on their website in their language? If you are Bangladeshi, you may go to Bangladesh Association’s webpage and find information on health issues, how to find resources, how to access health services. If you are Punjabi, go to Punjabi Association’s website. Community organizations should provide such services” (FG-11, Participant 3) |

| “If there is a website where there would some frequently asked questions in different languages then it would be easier to get answers to different health questions. . .then there would be a chat service, then we could get our answers right away. . .dedicated volunteers can be available at the chat services” (FG-05, Participant 5) | |

| Community engagement | “We have many doctors (IMG) in our community, they can contribute their time to the community members. For example, we know X, Y, Z are doctors. . .we can talk to them and they can guide us, they can provide preliminary suggestions. There are numbers of doctors, some of them are working professionally as doctors, some of them in other sectors, but if they decide that they will volunteer one day or two days and come to the community center and give advice, community members can benefit from them” (FG-01, Participant 1) |

Community-based health information workshops

FGD participants discussed that community organizations could arrange health education workshops and provide community members with information on health and well-being, how to avoid health risks, existing healthcare services, and how to access those services.

They also proposed that community organizations could prepare brochures on different health issues in different languages and distribute them at different social/cultural events when a number of community people gather. Distributing translated medical terminologies in multiple languages might help community members, as discussed by 2 FGD members.

A community information booth/center could be established where members of the community could find information related to health insurance, government benefits (eg, seniors’ benefits), and available resources.

Community-based interpreter services

Most participants indicated that language was a common barrier to accessing care. Community organizations could approach volunteers to provide interpreting services to those who have language barriers. Doctors’ clinics should also reach out to community organizations or community leaders to find volunteer interpreters to assist in their clinics or hospitals. Participants also suggested that international medical graduates (IMGs) could be hired as interpreters by healthcare providers.

Community support programs

Five FGD participants discussed different support programs community organizations could offer, for example, free ESL courses in the community and carpool services, especially to senior members of the community and newcomers.

Using social media

The role of social media to improve care access was also discussed among FGD participants. A community-based website could be developed to provide information, for example, health, legal advice, complaint booth, etc. Visual messages on health problems and important information could be posted on social media, for example, website, Facebook. Doctors from the community could be brought into the social network system to provide health information.

A chat system could be developed where community members could post their questions and get feedback within 24 h. Social media could also be an option to access interpreter services or find carpool and/or other services offered by community organizations.

Community engagement

The importance of community connection and involvement was mentioned in the FGDs. Participants discussed mobilizing community members and networking among different age groups. Health professionals could also help access information related to healthcare issues. Bangladeshi doctors could contribute to improving the health of community members by being accessible to them, for example, providing advice/knowledge over the phone or on social media. Also, volunteers could reach community members to determine their needs and provide information/education workshops.

Service provider-level approaches

FGDs suggested that healthcare providers, including doctors, nurses, and clinic/hospital staff, could support improving access to PHC services among immigrants (Table 4). Service providers could arrange interpreter services to improve communication gaps, hire staff from different cultural groups to increase cultural awareness among healthcare providers, and provide training to care providers and hospital/clinic staff to develop cultural competencies. The role of the doctor-patient-staff relationship in accessing healthcare was also discussed in the FGDs.

Table 4.

Solution Theme: Service Provider-Level Approaches Voiced by Focus Group Discussion Participants.

| Theme: Service provider-level approaches | |

|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

| Enhancing communication between patients and healthcare providers | “I think doctors should listen to the patients carefully to understand what the patient is trying to say. . .if doesn’t understand because of language or there is any communication gap or if I can’t make him understand he can say “I don’t understand what you are saying so I can’t identify your problem” (FG-02, Participant 5) |

| “It is important to provide quality care, just one or two questions are not sufficient. . .There should be more time for the patients. . . they should inquire if we understand what he is saying”. . .they should ask the patients, “are you satisfied”? If they ask such questions to the patients, it will come out, like how the patients feel. . . They just tell what happens and leave, never try to understand how we feel, if we are able to follow their instruction” (FG-01, Participant 1) | |

| “I am talking about interpreters. For example, we speak Bangla. If we find anyone at the hospital who speaks Bangla, any nurse or any staff at the hospital or clinic, it would be helpful” (FG-03, Participant 5) | |

| “At the clinic, staff from diverse backgrounds can be hired. If they speak different language or multi languages, then it would be easier to communicate. . .because one doctor can’t call another doctor who speaks same language as the patient does. But a doctor can call a staff who can serve as an interpreter” (FG-07, Participant 4) | |

| “Most Punjabi patients go to X clinic and I find that they have Punjabi receptionist who speaks Punjabi with the patients. Even doctors also speak Punjabi with the patients. Sometimes they ask me if I can speak Hindi. So I think why don’t they hire an interpreter who can speak Bangla and who can sit at the front desk?” (FG-06, Participant 5) | |

| Improving doctor-patient-staff relationship | “Time is a factor, patients should be given enough time. When patients are not given enough time they are on mental pressure. So they forget their needs, they should have enough time to talk about their problems. . .So, one patient, doctor comes fast and then she jumps to other room to other patient, so what happens then? This patient is losing her confident, so the patient is losing confident and what she is going to say. . .If I don’t say quickly then doctor will go to other room. Patient needs time to explain their need” (FG-07, Participant 2) |

| “My son had an operation, an ear surgery. The doctor was a white surgeon, He explained us nicely the benefits and the risk involved in the surgery. . .these information like what is your problem, what is the treatment, possible side-effects should be explained properly. If they give us time, talk nicely, patients feel better, even it cures half of your illness” (FG-06, Participant 1) | |

| “Yes receptionist, some of them are very good. But long ago I have an experience. Receptionist, they should be polite, they should be more caring, and they should be in the doing like they are in the healthcare process. So when one patient goes there (clinic), they have problem, they have so much hardship, so receptionist needs to be patience, they should be nice to them, make sure they detail all” (FG-07, Participant 2) | |

| Cultural competency | “Everybody should respect each other’s views and help. . .if I am sent to a female doctor and asked to say everything, being a male I may not feel comfortable. This is my view, my culture. Canada is a multicultural country and everybody needs to practice that. . .those who are in that positions, like doctors, nurse they also need to have awareness. So, those who are dealing with patients, you need to respect their views. Patients also need to be aware of the necessity of openness for the treatment purpose” (FG-01, Participant 3) |

| “We can see that immigrants and refugees have language problems, cultural difference. For refugee this has been a big problem. If doctors and nurses can adopt those culture or adopt some kind of communication strategies, would be better. . .not only interpreters, doctors from diverse background, languages can be hired” (FG-06, Participant 7) | |

Enhancing communication between patients and healthcare providers

Participants discussed that effective communication between doctors and patients was important for patient satisfaction and accessing care. Participants mentioned that doctors needed to be aware of the patient’s capacity to communicate his/her health conditions and follow through with medical recommendations. Healthcare providers could take different efforts to improve communication and help them explain their health problems.

Participants also identified that having an interpreter service at the doctor’s clinic and/or hospitals would be helpful to minimize the communication gap. The doctor’s office could ask the patient about using an interpreter. If the patient needed one, there could be an option for the patient to bring an interpreter or for the doctor’s office to arrange for an interpreter to be there. Moreover, multilingual staff from diverse backgrounds could be hired.

Improving doctor-patient-staff relationship

The importance of the doctor-patient relationship to improve care access was discussed by FGD participants. Participants mentioned that if doctors spent sufficient time listening to patients’ complaints and discussing treatment plans and the risks and side-effects of treatment, it could increase confidence and help patients make informed decisions. To improve the doctor-patient-staff relationship, doctors need to be empathetic to patients and culturally sensitive. It is also important that hospital or clinic staff be empathetic to patients.

Cultural competency

Three FG members suggested that doctors and nurses should receive training and education to develop cultural competencies. Frontline staff at clinics/hospitals also need to be culturally sensitive and empathetic to patients. Clinics and hospitals could hire more diverse and multilingual staff to improve multicultural awareness.

Policy-level approaches

The importance of government- or policy-level solutions was also highlighted in 11 FGDs (Table 5). FGD members most often discussed increasing the number of hospitals, after-hour clinics, urgent clinics, and doctors/nurses to improve quality of service and decrease wait time.

Table 5.

Solution Theme: Policy-Level Approaches Voiced by Focus Group Discussion Participants.

| Theme: Policy-level approaches | |

|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Quotes |

| Increased number of healthcare facilities and care providers | “I think we need more hospitals. . .we don’t have enough hospitals that is why there is so long wait time. . .my husband had abdominal pain, we went to X hospital and they left us there for 8-9 h without any treatment, next time we drove to Canmore, a 1-1/5 h drive, but they say my husband immediately. Did the MRI, CT scan and then diagnose cancer, an advance colon cancer. He was admitted there and had his surgery. If we went to any hospitals in Calgary, my husband would have died. . .there is not enough hospital in Calgary. We are a large population here but not enough number of hospitals” (FG-01, Participant 03) |

| “Government can increase number of facilities. . .like after hour clinics, I am not sure if it is termed as after clinic or community clinic, like in different quadrants of the city for multiple communities which will provide after hour services. . .not that emergency but, for example, minor and less emergency issues” (FG-04, Participant 05) | |

| “Government needs to employ more doctors, thus the wait time can reduce and we don’t suffer. They can also hire qualified immigrant doctors. . .they can hire international doctors and can supervise them to assess their quality” (FG-01, Participant 4) | |

| “Now as with increased population, it is difficult to get appointment to lab services. . .there should be more lab services and the lab hours needs to be increased, for example 8 am-9 pm” (FG-06, Participant 8) | |

| Decentralizing the practice of family doctors | “Government can do, for example, equal distributions of family physician to the community. What I want to say, family doctors who are South Asian, for example from Bangladesh or India, they want to practice in North East. They don’t practice in North West. . .they don’t want to come on other side. Therefore, there is lack of diversity. So, if you live in North West, you won’t find a doctor who speaks your language. Government can control it” (FG-05, Participant 4). |

| Health data sharing | “If I go to any walk-in clinic, the doctors should have access to my health information. . .it is important that they have access to my medical history, what medicine I am taking. If not, I will not be comfortable to go the doctors at walk-in clinic. If they have access, I may not to go to my family doctor all the time, there will be no long wait time” (FG-1, Participant 5) |

| “If we go to other doctors, like not our family doctor, they say that they need to get health record from our family doctor. . .patients information is not available online. Even if you change your doctor, they send fax request to get the record and sometimes it costs you. It should be accessible to any doctors, family doctor and walk-ins” (FG-5, Participant 4) | |

Increased number of healthcare facilities and care providers

Participants felt that there were insufficient hospitals and after-hour clinics to meet their needs and that there was a shortage of healthcare providers, which impacted their access to care services and increased wait time and patient suffering. Therefore, it was important to them that there be more facilities and care providers proportionate to the number of patients.

Participants from 1 FGD suggested increasing diagnostic services, including the number of diagnostic/laboratory centers, and service hours proportionate to the size of the community.

Decentralizing the practice of family doctors

Participants also discussed that the local government or provincial health services could control the location at which family doctors practice, which could improve the equal distribution of physicians in the community.

Health data sharing

Two FGD members suggested that health data needed to be accessible to walk-in doctors to improve treatment and patient satisfaction. It could also lower the workload of family doctors and shorten the wait time to get appointments with family physicians.

Discussion

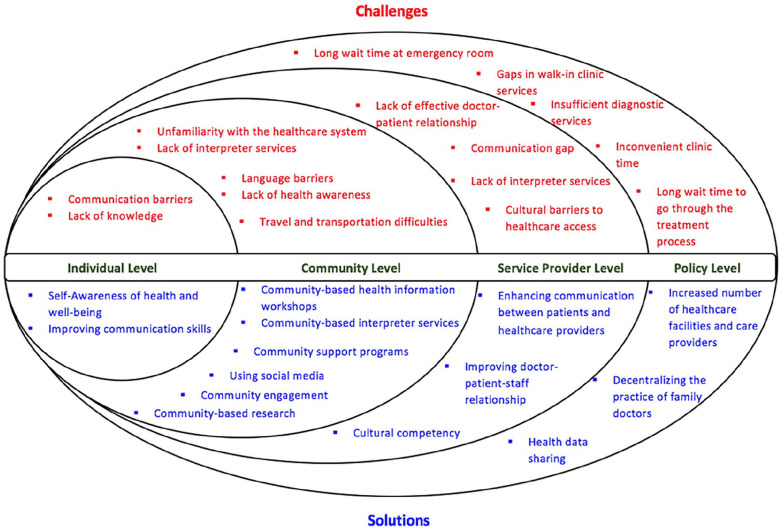

Using a participatory approach of conducting research in the community, for the community, and with the community, we engaged with immigrant community subgroups to identify perceived solutions to improve their access to PHC. FGD participants suggested approaches at different levels: individual, community, service provider, and policy. Figure 1 illustrates the focus of the proposed solutions and mirrors them with the challenges the immigrant community has reported facing while accessing primary care in Canada.6,15,16

Figure 1.

Proposed solutions put forward by study participants and mirroring those with the reported challenges faced by immigrant communities while accessing primary health care in Canada. The Social Ecological Model has been adapted from the original model described by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).16

Community-level approaches mentioned by FGD participants were community-based health information workshops, interpreter services, support programs, using social media, and community engagement. Previous studies have identified that having a lack of knowledge regarding the healthcare system is a barrier to PHC access amongst immigrants, and study participants felt that having information sessions within the community could mitigate this obstacle by increasing their health literacy and their awareness of available health resources and insurance. One study assessed the effectiveness of health information workshops in a Chinese community in the United States, touching on topics such as nutrition, depression, elder abuse, breast cancer, and stroke.17 Findings showed that participants’ knowledge and awareness of the topics addressed greatly increased after completing the workshops.17 FGD participants also mentioned that it would be helpful to have such workshops conducted by knowledgeable community members. A study by Woodall et al18 stated that community health champions acted as a catalyst in a program to improve the lifestyles of individuals and the community. FGD participants in the current study also stated the importance of having volunteer-based interpreter services to account for existing language barriers that impede their health. One study observed that rates of fecal occult blood testing, rectal exams, and flu immunization significantly increased in limited-English proficiency Portuguese and Spanish patients after implementing 2 years of interpreter services.19 After the 2 years, the rates for patients with limited-English proficiency were much closer to that of fluent English-speaking patients.19 Some FGD participants mentioned that having support programs, such as providing free ESL courses and helping newcomers and seniors better understand the available resources, could bridge a current gap they face. One study also recommended implementing social support programs to improve the mental health of immigrants in Canada.20 Additionally, FGD participants in our study recommended using social media as a potential solution to decrease health disparities amongst immigrants. They suggested having websites and forums to discuss health concerns, disseminate health information, and opt-in for interpreter or carpool services. A systematic literature review described social media as a double-edged sword, as it can demonstrate benefits as well as adverse effects on health.21 Some positive effects of using social media for health that have been mentioned include convenient information gathering and comfort, whereas some negative effects include being exposed to inaccurate information and spending too much time on social media, thus neglecting other important work and healthy activities.21 Finally, our Bangladeshi-Canadian participants also mentioned the importance of community engagement to mobilize community members. They suggested that Bangladeshi doctors and IMGs could contribute some time to provide important lectures or advice to community members at community centers. One study determined that community engagement can help increase healthy behaviors among disadvantaged populations when correctly planned and employed.22

Service provider-level approaches mentioned by FGD participants included improved communication between patients and healthcare providers, improved doctor-patient-staff relationships, and increased cultural competence. Participants felt that, due to language barriers, they are often unsatisfied with their level of care. They mentioned that doctors should be clear if they are unable to understand a patient, and interpreter services could be utilized to close communication gaps. They suggested hiring healthcare professionals of various backgrounds to accommodate the diverse patient population. To create approaches to improve communication between healthcare providers and patients, one study recommended that doctors initially take a step back and try to understand why communication issues exist in the first place.23 Study participants also noted that they would like more time to explain their needs. Charles et al23 noted that doctors should create an open atmosphere so that the patient can freely discuss their concerns and be understood. FGD participants stated that improved doctor-patient relationships through empathetic communication could help them gain better access to PHC. Effective communication between doctors and patients can help create trustworthy relationships.23,24 Our FGD participants suggested that healthcare providers receive cultural competence training to be more culturally sensitive and empathetic toward their patients, thus increasing patient satisfaction. A study by Bentley and Ellison25 showed that nursing students’ cultural competence scores significantly increased after the implementation of an elective cultural competence course with a cross-cultural immersion experience. In another study, nurses reported that they felt better equipped to serve the needs of diverse patients upon receiving cultural competence training.26

Policy-level approaches identified by FGD participants included increasing the number of healthcare facilities and care providers, decentralizing the practice of family doctors, and sharing health data. Adding more clinics and doctors could address the long wait times patients often face. Previous studies showed that long wait times especially affect immigrant families, as they already struggle to find a work-life balance.27,28 Adopting a strategic approach to setting up the clinics of family doctors across localities would serve to improve the distribution of South Asian doctors across the city. One study demonstrated that Black and Hispanic Americans preferred visiting physicians with similar ethnic backgrounds, not simply because they were located in their neighborhoods, but due to personal preferences.29 They also suggested that to accommodate this need, changes in medical school policies should be implemented to increase the number of visible minority doctors.29 FGD participants mentioned that patient satisfaction could be increased by implementing electronic health records, as this could reduce wait times and costs when visiting walk-in doctors. Burton et al.30 of another study agreed that the use of electronic health records could largely improve the quality and coordination of care.30 They also noted some potential barriers present in the face of this application, such as not having a standard way to record clinical information, maintenance costs, and patient concerns about the loss of privacy.

Our study tried to establish a safe environment to allow for open communication of FGD participants. FGDs were administered in Bangla, but participants had the option of speaking in Bangla or English. Moderators were fluent in both Bangla and English. This approach was utilized to promote comfortable communication amongst participants. Although we tried to create a trustworthy atmosphere, a possible limitation is that participants may have held back due to social desirability bias. The fact that our study population was limited to Bangladeshi immigrant needs to be kept in mind as they may not be representative of other immigrant populations in Canada. Within the Bangladeshi-Canadian diaspora, the study sample predominantly represents married, educated, Muslim, Bangla speaking immigrants over the age of 25 living in an urban center. This sample characteristic is not surprising due to the immigration criteria under which a substantial number of immigrants migrated into Canada. The point-based immigration criteria favored migrants who are educated, married, and had work experiences. Despite the limitation regarding generalizability, our study contributes toward understanding the broad action items which would benefit any subpopulation against the challenges they face regarding equitable access to primary healthcare. Nonetheless, further research is recommended to extrapolate the results to different groups of immigrants, as well as across the country, as immigrants in different provinces may experience different barriers and suggest other solutions. A meaningful community-engaged program of research of identifying solutions aims to ensure citizen engagement and empowerment for solution-oriented interventions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the wholehearted engagement and gracious support we have received from the Bangladesh-Canadian community members in Calgary. Also, we appreciate the compassionate encouragement we have received from all the socio-cultural organizations belonging to this community including the leadership of Bangladesh Canada Association of Calgary (BCAOC).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study has been supported from grant from Canadian Institute of Health Research (201612PEG- 384033).

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of University of Calgary before commencing any research activity (Ethics ID: REB15-2325).

ORCID iD: Tanvir C Turin  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7499-5050

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7499-5050

References

- 1. Sofaer S. Navigating poorly charted territory. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:75S-93S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batista R, Pottie K, Bouchard L, Ng E, Tanuseputro P, Tugwell P. Primary health care models addressing health equity for immigrants: a systematic scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20:214-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aptekman M, Rashid M, Wright V, Dunn S. Unmet contraceptive needs among refugees crossroads clinic experience. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:e613-e619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell RM, Klei A, Hodges BD, Fisman D, Kitto S. A comparison of health access between permanent residents, undocumented immigrants and refugee claimants in Toronto, Canada. J. Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hartman LB, Shafer MA, Pollack LM, Wibbelsman C, Chang F, Tebb KP. Parental acceptability of contraceptive methods offered to their teen during a confidential health care visit. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:251-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed S, Shommu NS, Rumana N, Barron GR, Wicklum S, Turin TC. Barriers to access of primary healthcare by immigrant populations in Canada: A literature review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:1522-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World health organization, Regional office for Europe. Community Participation in Local Health and Sustainable Development: Approaches and Techniques. WHO regional office for Europe. 2002. Accessed February 21, 2021. https://apps.Who.Int/iris/handle/10665/107341 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Lindquist-Grantz R, Parsons A, Melink K. Immigrants as research partners: A review of immigrants in community-based participatory research (CBPR). J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:1457-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian institutes of health research. Guide to knowledge translation planning at cihr: integrated and end-of-grant approaches. 2015. Accessed July 15, 2020. http://www.Cihr-irsc.Gc.Ca/e/45321.html

- 10. Jaye C. Doing qualitative research in general practice: methodological utility and engagement. Fam Pract. 2002; 19:557-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong LP. Focus group discussion: a tool for health and medical research. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:256-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruff CC, Alexander IM, McKie C. The use of focus group methodology in health disparities research. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:134-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carey M. The group effect in focus groups: planning, implementing, and. Crit Issues Qual Res Methods. 1994;225:41. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hogg W, Rowan M, Russell G, Geneau R, Muldoon L. Framework for primary care organizations: The importance of a structural domain. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2008; 20: 308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention. 2020. Accessed February 21, 2021. https://www.Cdc.Gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.Html

- 17. Dong X, Li Y, Chen R, Chang ES, Simon M. Evaluation of community health education workshops among Chinese older adults in Chicago: a community-based participatory research approach. J Educ Train Stud. 2013;1:170-181. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Woodall J, White J, South J. Improving health and well-being through community health champions: a thematic evaluation of a programme in Yorkshire and Humber. Perspect Public Health. 2013;133:96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-english-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:468-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reitmanova S, Gustafson DL. Mental health needs of visible minority immigrants in a small urban center: recommendations for policy makers and service providers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:46-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leung R, Li J. Using social media to address asian immigrants’ mental health needs: a systematic literature review. J Nat Sci. 2015;1:e66. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AM. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charles C, Gafn A, Whelan T. How to improve communication between doctors and patients: learning more about the decision making context is important. BMJ. 2000;320:1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahmed S, Lee S, Shommu N, Rumana N, Turin T. Experiences of communication barriers between physicians and immigrant patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Patient Exp J. 2017;4:122-140. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bentley R, Ellison KJ. Increasing cultural competence in nursing through international service-learning experiences. Nurse Educ. 2007;32:207-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaihlanen A-M, Hietapakka L, Heponiemi T. Increasing cultural awareness: qualitative study of nurses’ perceptions about cultural competence training. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A, Abrahamowicz M, Tousignant P, Lynch J. Access to health-care in canadian immigrants: a longitudinal study of the national population health survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19:70-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brar S, Tang S, Drummond N, Palacios-Derflingher L, Clark V, John M, et al. Perinatal care for south asian immigrant women and women born in Canada: telephone survey of users. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:708-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? To provide the kind of care consumers want, medical schools might be able to justify using race as an admissions criterion. Health Aff. (Millwood). 2000;19:76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burton LC, Anderson GF, Kues IW. Using electronic health records to help coordinate care. Milbank Q. 2004;82:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]