Abstract

Background:

Studies on the experiences of consumers with Motor Neurone Disease Associations at end of life and bereavement are lacking, and their role and capability within the broader sectors of health and disability are unknown.

Objectives:

To ascertain the experiences and views of bereaved motor neurone disease caregivers with Motor Neurone Disease Associations about service gaps and needed improvements before and during bereavement and to propose a model of care that fits with consumer preferences and where Motor Neurone Disease Associations are effective enablers of care.

Methods:

A national bereavement survey was facilitated in 2019 by all Motor Neurone Disease Associations in Australia. A total of 363 respondents completed the section on support provided by Motor Neurone Disease Associations. A mixed-method design was used.

Results:

Respondents were generally positive about support received before bereavement (73-76%), except for emotional support (55%). Positive experiences related to the following: information, equipment advice/provision, advocacy/linking to services, showing empathy/understanding, personal contact and peer social support. Negative experiences included lack of continuity in case management and contact, perceived lack of competence or training, lack of emotional support and a lack of access to motor neurone disease services in rural areas. Suggested improvements were as follows: more contact and compassion at end of life and postdeath; better preparation for end of life; option of discussing euthanasia; providing referrals and links for counseling; access to caregiver support groups and peer interaction; provision of a genuine continuum of care rather than postdeath abandonment; guidance regarding postdeath practicalities; and more access to bereavement support in rural areas.

Conclusion:

This study provides consumer perspectives on driving new or improved initiatives by Motor Neurone Disease Associations and the need for a national standardised approach to training and service delivery, based on research evidence. A public health approach to motor neurone disease end-of-life care, of international applicability, is proposed to address the needs and preferences of motor neurone disease consumers, while supporting the capability of Motor Neurone Disease Associations within a multidisciplinary workforce to deliver that care.

Keywords: bereavement support, consumer perspective, emotional support, end-of-life care, family caregivers, motor neurone disease advisors, Motor Neurone Disease Associations, motor neurone disease, practical support, public health approach

Background

People with motor neurone disease (PwMND) are one of the most vulnerable patient groups because from diagnosis, they face the rapid progression of profound disability and death, as illustrated by the quote of a person living with motor neurone disease

Imagine being told you or your loved one will lose the ability to move, to speak, to swallow, to breathe; that the order and pace of losses cannot be predicted. I was not given a personal prognosis: a small percentage of people with MND live for decades, some live for weeks, the median is around 2-3 years.1

Likewise, their family caregivers are one of the most challenged caregiver groups facing physical, psychological and social strain, before and during bereavement.2

Despite the inexorable mortality associated with MND from the time of diagnosis, end-of-life (EOL) outcomes are reported to be poor for PwMND and family caregivers. Barriers to providing and receiving high-quality EOL care are multiple and complex. At a system level, there is a disconnect between health, disability and aged care services,3 with PwMND frequently caught between these service sectors with none taking responsibility for EOL care provision.4 The six MND Associations in Australia, as not-for-profit or third-sector community-based organisations, play a vital role in helping families navigate these complex systems (NDIS or the National Disability Insurance Scheme for those under 65 years and My Aged Care for those aged 65 years and above), and provide advocacy, equipment including digital and assistive technologies, information, education, practical and emotional support. The MND Associations are closely integrated with specialised multidisciplinary MND Clinics that care for most PwMND in each Australian state with their MND Advisors often being part of these health care teams.5 MND advisors also help MND families navigate the systems of palliative care, primary care and community care. However, these Associations are in general poorly resourced and rely mainly on fundraising, which is financially erratic, and therefore, the nature and extent of support differ between Australian states.6

In Australia, the overall prevalence of MND is estimated to be 8.7/100,000 Australians, and there are currently just over 2,000 people and their families living with the disease.5 However, at least three times as many families stay grappling with grief following this traumatic experience, many of them agonising over what could have worked better.7 Notwithstanding the physical, psychological and emotional burden of the disease on MND family caregivers, the Deloitte Access Economic Report8 has quantified the economic disadvantage on families supporting people with MND in Australia. These caregivers provide an estimate of 7.5 h of informal care per day with the productivity loss estimated at $68.5 million in 2015, or $32,728 per person, with families shouldering most of these costs ($44.0 million) and with government bearing the rest ($24.5 million) in the form of lost taxes.

Despite this burden and contribution to the economy, caregivers’ role is generally not appreciated and is undervalued by the health industry and governments. Moreover, despite the importance of consumer perspectives and support for community engagement and involvement of informal caregivers in services, most current models of care still fall short of meeting community needs because consumers are only consulted as clients or only involved in committees,9,10 rather than partners in the co-design of services.11

MND caregivers’ needs before and after bereavement are largely overlooked. During caregiving, their assessed top priorities for support were ‘knowing what to expect in the future’, ‘knowing who to contact if concerned’, ‘equipment to help care’, ‘dealing with your feelings and worries’ and ‘having time to yourself in the day’.12 However, no organisation is systematically assessing and addressing their support needs as part of standard practice.

Recent investigations of MND caregiver support needs after bereavement have revealed concerning gaps between what is required and what is received. A large national survey of bereaved MND caregivers found that approximately 40% did not feel their support needs were being met by the professional and support services available to them. A majority of participants (63%) required bereavement support beyond their family and social networks.7 Most had accessed support from family and friends, followed by MND Associations, general practitioners (GPs) and funeral providers. While informal supports were considered the most helpful, sources of professional help were the least used and were perceived to be the least helpful.7 More alarmingly, bereaved MND caregivers were found to be at higher risk of Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) than the general bereaved population.2 This condition was associated with reported deterioration in their physical (31%) and mental health (42%).

Although MND Associations were frequently accessed for support (78%), 44% of bereaved caregivers reported that these were unhelpful.7 Emotional support is one of the primary expectations of service users in MND care, and MND Associations are in prime position to offer such support for caregivers before and after death of PwMND.6,13,14 However, the extent and quality of emotional and other support have not been systematically assessed to date. In fact, a 2018 Navigation Strategy Discussion Paper in Western Australia stated that ‘Evidence of effectiveness of any community-based service delivery models in progressive neurological disease was extremely weak in the literature reviewed’.15

Therefore, the role and potential capability of third-sector organisations such as MND Associations in providing ongoing support in EOL care and beyond to bereaved caregivers requires investigation. A first step towards this is to ascertain the views and experiences of MND caregivers with MND Associations to determine service gaps and ways to improve support for caregivers before and during bereavement, through an appropriate model to EOL care.

Objectives

The objectives were to:

Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of existing EOL and bereavement services provided by MND Associations, based on the experiences of bereaved MND caregivers.

Identify key challenges and gaps in the provision of EOL and bereavement services provided by MND Associations, based on the experiences of bereaved MND caregivers.

Determine how EOL and bereavement service delivery can adapt and improve to meet the MND community needs and expectations.

Propose a model of care which addresses the needs and preferences of MND consumers, while supporting the capability of the MND Associations within a multidisciplinary workforce to deliver that care.

Methodology

An anonymous national population-based cross-sectional postal and online survey of bereavement experiences of family caregivers who had lost a relative/friend to MND (2016–18) was undertaken in 2019. A total of 1,404 study packages were posted by five MND Associations in Australia; 393 valid questionnaires were returned making up a 31% response rate.

The questionnaire contained eight sections covering a range of experiences with services and unmet needs, with one section focusing on the experience with MND Associations. This article describes the results from this section and adopts a mixed-method design consisting of quantitative questions on perceptions of support and helpfulness they received from MND Associations, and also open-ended questions for qualitative feedback on their positive or negative experiences.

Quantitative questions used a 4-point Likert-type scale, with response categories from ‘not supported’ or ‘not helpful’ to ‘very supported’ or ‘very helpful’. Response categories to question on extent of value put on several aspects of service ranged from ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘quite a bit’ to ‘a lot’. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were obtained using SPSS Statistics Version 26 for demographic variables and experiences of support. Questions with open-ended responses were subject to conventional content analysis, with each response read and coded by one of the authors (P.A.C.).16 After coding was completed, codes were revised, and themes based on the codes were devised. A second author (S.M.A.) coded the responses to ensure accuracy and minimise bias.

Ethics approval was granted by La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC19022). As this was an anonymous postal and online survey, returning the completed survey was considered as implied consent. The information sheet that accompanied the survey emphasised that participation was entirely voluntary.

Results

Ninety-two percent (n = 363) of overall survey respondents completed the section regarding their experiences with MND associations.

Respondents’ profile

Of the 363 bereaved caregivers (mean age: 63.7, standard deviation [SD]: 12.1, age range: 22–90 years), the majority were female (72.5%), retired (53.9%), widowed (72.7%) and Australian (78.6%) (Table 1). About a third had a university education. Their relationship to the deceased was mostly as a spouse/partner (74.0%) or child of the deceased (19.2%). The mean period since the death of the patient was 1.7 years (SD: 0.8). The mean age of the deceased was 68.8 years (SD: 10.6), with an age range of 32–94 years. More than half of the deceased were male (58.4%). The majority of respondents were from New South Wales (35.1%) followed by Victoria (27.6%) (Table 1), reflecting proportions of the MND population in Australian states, though an overall 38% of respondents from these states were from rural areas.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the bereaved and deceased.

| Total n | Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| Bereaved | ||

| Age (years) | 363 | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.7 (12.1) | |

| Median (min, max) | 66.0 (22.0, 90.0) | |

| Sex: n (%) | 363 | |

| Male | 100 (27.5%) | |

| Female | 263 (72.5%) | |

| State: n (%) | 362 | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 8 (2.2%) | |

| New South Wales | 127 (35.1%) | |

| Northern Territory | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Queensland | 52 (14.4%) | |

| South Australia | 35 (9.6%) | |

| Tasmania | 10 (2.8%) | |

| Victoria | 100 (27.6%) | |

| Western Australia | 29 (8.0%) | |

| Urban/rural: n (%) | 362 | |

| Urban | 210 (62.0%) | |

| Rural | 152 (38.0%) | |

| Marital status: n (%) | 362 | |

| Never married | 10 (2.8%) | |

| Married or defacto | 75 (20.6%) | |

| Separated or divorced | 14 (3.9%) | |

| Widowed | 263 (72.7%) | |

| Cultural background: n (%) | 359 | |

| Australian | 282 (78.6%) | |

| Other English speaking | 51 (14.2%) | |

| Non-English speaking | 26 (7.2%) | |

| Highest level of education: n (%) | 359 | |

| No formal education | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Primary school | 9 (2.5%) | |

| High school | 110 (30.6%) | |

| Diploma/certificate/trade qualification | 129 (35.9%) | |

| University degree | 108 (30.2%) | |

| Employment: n (%) | 360 | |

| Working full time | 69 (19.2%) | |

| Working part time | 64 (17.8%) | |

| Caregiver | 11 (3.1%) | |

| Student | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Temporarily unemployed | 8 (2.2%) | |

| Retired | 194 (53.9%) | |

| Other permanently unemployed | 12 (3.3%) | |

| Relationship to deceased: n (%) | 362 | |

| Spouse/partner | 268 (74.0%) | |

| Parent | 14 (3.9%) | |

| Sibling | 7 (1.9%) | |

| Child | 69 (19.2%) | |

| Friend | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Other | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Period of bereavement (years): | ||

| Mean (SD) | 361 | 1.7 (0.8) |

| Median (min, max) | 1.7 (0.4, 3.4) | |

| Period of bereavement (category): | 361 | |

| 5 to <12 months | 89 (24.6%) | |

| 12 to <24 months | 132 (36.6%) | |

| 24+ months | 140 (38.8%) | |

| Deceased | ||

| Age (years) | 361 | |

| Mean (SD) | 68.8 (10.6) | |

| Median (min, max) | 70.0 (32.0, 94.0) | |

| Sex: n (%) | 361 | |

| Male | 211 (58.4%) | |

| Female | 150 (41.6%) | |

SD, standard deviation.

Perceptions of support and helpfulness of MND Associations

Timing of initial contact with MND Association

Eighty percent of respondents indicated that they contacted their local MND Association at the diagnosis of their care recipient. Over 17% of caregivers did not connect with the MND Association until at least the middle to end stages of their care recipient’s disease. The remaining 10 respondents (2.8%), either connected with another support organisation or did not have contact with their local MND Association.

Perception of support before and after bereavement

Twice as many caregivers felt more supported by MND Associations before bereavement than after bereavement. Only a few did not feel supported at all before bereavement compared to almost four times as many after bereavement (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perception of support by caregivers as a result of services provided by the MND Association before and after bereavement.

| Felt supported before bereavement | Felt supported after bereavement | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Not supported | 32 (9%) | 121 (34.8%) |

| Quite supported | 71 (20.1%) | 51 (14.7%) |

| Somewhat supported | 95 (26.8%) | 102 (29.3%) |

| Very supported | 156 (44.1%) | 74 (21.3%) |

| Total | 354 (100%) | 348 (100%) |

MND, motor neurone disease.

Helpfulness regarding decision-making in EOL care

Just over a half of caregivers considered the services provided by the MND Associations to be ‘very helpful’ for decision-making regarding EOL care while one-third of them found the services to be ‘quite or somewhat helpful’ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Helpfulness to make more informed and better decisions to manage partner/relative/friend’s EOL care.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Not helpful | 31 | 8.7 |

| Quite helpful | 69 | 19.3 |

| Somewhat helpful | 62 | 17.4 |

| Very helpful | 195 | 54.6 |

| Total | 357 | 100 |

EOL, end of life.

Extent of support meeting caregivers’ expectations during EOL or bereavement

Over half of respondents (55%) reported that the support at EOL met their expectations ‘quite a bit/a lot’, compared to 43% during bereavement. Interestingly, approximately one quarter of the sample did not believe that support during EOL from the MND Association was applicable to them (Table 4).

Table 4.

Expectations met at EOL and during bereavement.

| Expectations met at EOL | Expectations met during bereavement | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Not at all | 59 (22.3%) | 83 (28.7%) |

| A little | 61 (23.0%) | 82 (28.4%) |

| Quite a bit | 58 (21.9%) | 59 (20.4%) |

| A lot | 87 (32.8%) | 65 (22.5%) |

| Total | 265 (100%) | 289 (100%) |

EOL, end of life.

Aspects of service valued by caregivers

For those who responded to this question (86%), most aspects of the services provided by the MND Associations were valued by caregivers to the same extent; that is, 73–76% valued being visited at home, the personal contact, the time dedicated to the visit, the proactive approach anticipating needs and practical support. In contrast, emotional support was valued as helpful by only 55% of respondents (Table 5).

Table 5.

The value (being quite a bit/a lot) placed by caregivers on service aspects of the MND Associations.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Being visited at home | 228 | 73.8 |

| The personal contact | 249 | 76.1 |

| The time dedicated to the visit | 237 | 76.2 |

| The proactive approach anticipating your needs | 228 | 73.1 |

| The practical support | 242 | 76.3 |

| The emotional support | 145 | 54.7 |

MND, motor neurone disease.

Qualitative feedback

Respondents were asked to comment on the practical and/or emotional ways that they were assisted by MND Associations before bereavement. Positive and negative views of their experiences with this assistance are summarised in Table 6. Exemplar participant quotes to support the themes are provided.

Table 6.

Themes summarising the positives and negatives experienced by caregivers.

| What is working well | What is NOT working well |

|---|---|

| Provision of Information | Lack of continuity in case management and contact |

| Equipment advice and provision | Perceived lack of staff competence and training |

| Advocacy and linking to services | Lack of emotional support |

| Showing empathy and understanding | Lack of access to MND services in rural/regional areas |

| Peer social support |

MND, motor neurone disease.

A. Ways caregivers felt supported by their MND Association

Six positive themes emerging from the analysis were as follows: (1) provision of information, (2) equipment advice and provision, (3) advocacy and linking to services, (4) showing empathy and understanding, (5) personal contact and (6) peer social support.

Theme 1A: provision of information

Respondents perceived practical benefits from the information provided by MND Associations. The information was valued in a number of domains, with respondents benefitting from specific and timely education regarding MND (‘Caregiver training extremely helpful with emphasis on information and skills acquired before they were required’) and training courses relevant to the caregiving role (‘Very practical information on how to assist my wife’). Reading materials were also reported to be of practical use (‘We appreciated most of all the information brochures available including recipes as swallowing became an issue’).

Respondents also perceived benefits associated with the provision of information for health professionals (‘I valued the way in which our MND support person supported us both & was an essential information resource for our health practitioners’). A further practical benefit was the readily available informational support provided by the MND Associations (‘Always being available & willing to answer questions & deal with problems as they arose’). This information was disseminated in several formats, with caregivers appreciating the facilitation of access to information, education, reading material and information sessions.

Theme 2A: equipment advice and provision

A strong theme was the practical benefit derived from equipment provision and support from the MND Associations. Respondents noted benefits for both themselves and their care recipients (‘Meeting our needs with equipment which made my life easier and made my partner able to be as comfortable as possible’), particularly when equipment needs were addressed promptly (‘The provision of equipment was extremely well handled, waiting times were minimal’; ‘Responded to my call for home adjustments, ramps, bed etc. promptly’) and assisted caregivers in their role (‘Timely provision of hospital bed took an enormous load off me having to organise one’). Respondents noted that the MND Associations provided them with essential equipment that they would not otherwise be able to afford, as well as guidance regarding the equipment.

Theme 3A: advocacy and linking to services

Respondents noted benefits from the advocacy provided by the MND Associations as well as the linking and coordination of relevant services. Respondents appreciated MND Association involvement in promoting timely services (‘advocacy to get PEG quickly when needed’; ‘MND Association did help fast track [patient name] appointment that led to diagnosis’; ‘Advising Nursing Home, getting help with speech therapy and bringing Palliative Care on board’) and assisting with the application for services (‘Assistance with ACAT and respite options’; ‘NDIS application’). The provision of linkages to relevant services (‘provided advice to us of different organisations that may be of assistance to us’) as well as assistance with the coordination of these services were perceived as beneficial by respondents (‘sleep apnoea testing, provision of PEG feeds’; ‘helped make appointments’; ‘Assisted with contacts, OT assessments, and links to MND clinic’).

Theme 4A: showing empathy and understanding

Respondents benefitted from competent demonstrations of emotional support by MND Advisors. In particular, listening and empathy were valued (‘MND representative was emotionally supportive as she was empathetic to our situation’), and interactions with staff could lift spirits (“[Advisor Name] was kind, warm, cheeky, knew what to say. Would bring a smile to Dad’s face”). This support was perceived as helpful in terms of emotional preparation (‘Emotionally educated us in expectations and provided great empathy’). Caregivers appreciated ‘very compassionate’ staff who exhibited ‘empathy and understanding’. Respondents noted benefit from interactions with skilled staff (having a personal counsellor from MND association’ who demonstrated a ‘unique ability to put people at ease).

Theme 5A: personal contact

Respondents commonly noted benefit from personalised contact from MND Associations. This contact could be in the form of phone calls, visits and personal letters (‘The follow up phone call and visit after mum passed was lovely’; ‘many phone conversations which all provided us with the support we needed at the time’; ‘The visits were wonderful. So caring and supportive and only a phone call away too’; ‘MND Assoc was very kind to send condolence letter’).

Theme 6A: peer social support

Caregivers support group meetings and interactions were perceived to be beneficial (‘Group lunch for the bereaved was a big help’); particularly if conducted by a trained facilitator (‘I think peer groups can be effective if led by the “right” expert’). The opportunity to interact with peers in a similar position was also considered valuable (‘Contact with other caregivers and persons with MND who were going through the same thing’).

B. Ways caregivers were NOT supported by their MND Association

Themes revealing negative aspects of support included the following: (1) lack of continuity in case management and contact, (2) perceived lack of competence or training, (3) lack of emotional support and (4) a lack of access to MND services (rural/regional).

Theme 1B: lack of continuity in case management and contact

Some respondents experienced a lack of continuity in their case management from MND Associations, leading to some dissatisfaction with the service. In some cases, support from the MND Association ceased (‘Initially we had a wonderful advisor. However, when he left, we did not receive any further support’), while other respondents were unimpressed with staff replacements (‘Our MND advisor visited monthly & then left her position. We did not meet her replacement but did have one phone call’).

Some respondents stated that they did not have sufficient contact. This lack of contact was characterised as insufficient phone or home visits (‘So really I had no real contact with MND association’; ‘None, like they forget you were there, a bit disappointed’; MND advisor visited once – no other contact!; “felt neglected”). A lack of perceived contact was also evident post-bereavement (‘My contact person left and was not replaced in time to make contact after my husband’s death’).

Theme 2B: perceived lack of staff competence or training

There was a perception that some MND Association staff lacked competence and training. A lack of knowledge from staff was concerning (‘Often we knew more than our MND advisor’) and led to a low perception of benefit from MND Association services (‘Very little – a brand new person who knew almost nothing about MND, and almost nothing about supporting us’). Staff consistency in experience was also noted (‘New nurse had no real experience in MND. Physiotherapist same, first OT had no MND experience’), while other respondents questioned the value of the advice they received (‘I felt that having private conversations with other caregivers was more beneficial than some of the “professional” advice’).

Respondents perceived a lack of MND Advisors’ competence and training in particular areas such as emotional support (‘The people from MND association alarmed me, whereas the [community organisation] nurses were very reassuring’), meeting facilitation (‘The MND rep had no idea how to conduct a meeting’), disease-specific advice (‘The MND representative didn’t really understand Mum’s MND type so wasn’t able to be practical or proactive’).

Theme 3B: lack of emotional support

Some caregivers indicated that emotional support was not always present. They stated that they did not receive any emotional support at all (‘I don’t think I gained any real emotional support’), while others commented on a perceived lack of staff competence or training in this domain (‘Our MND advisor and original OT were very helpful. All the time, but some of the others I don’t think really understood the real pressures felt at home living with the dreaded disease’; ‘a very pleasant, young man called on us at home again. But he went too far in explaining prognosis. We were aware of MND progress as we had a cousin with the condition. But the MND representative was determined to complete his spiel even though I tried to step in as it was causing us both distress’). Consequently, some respondents reported that emotional support was dependent on the competence of the individual staff member (‘It depended on the person assigned. Some good, others not overly concerned’).

Theme 4B: lack of access to MND services (rural/regional)

Respondents in rural and regional areas noted the lack of services and contact available in their area (“it was just a shame that we lived so far away from [capital city] that when she did come round, she only had 15-20 minutes. She did a fantastic job, and I hope that more coordinators can attend rural communities more”; didn’t even see or hear from a regional adviser’; ‘we do not live in capital city so MND Association contact was minimal’) leading some in nonmetropolitan areas feeling neglected (‘I believe weren’t interested in the people in regional areas’; ‘In a regional area it is impossible for a caregiver to access the programmes offered by the MND Association which do not offer programmes more than 100 km away’; ‘Nobody visited us at home. We live in a rural area’).

Improvements suggested by caregivers

Caregivers gave their views on ways EOL care and bereavement support can be improved (Table 7).

Table 7.

A summary of suggested improvements by caregivers regarding the support of MND Associations at EOL and during bereavement.

| Support at EOL | Bereavement support |

|---|---|

| More personal contact and involvement from MND Associations | More contact and compassion postdeath from MND Associations |

| Euthanasia option | Providing referrals and links for counseling |

| Better preparation for EOL | Access to caregiver support groups and peer interaction |

| Health professionals need to show more compassion and be trained appropriately | Provision of a genuine continuum of care rather than postdeath abandonment |

| Guidance regarding postdeath practicalities | |

| More access in rural/regional areas |

EOL, end of life; MND, motor neurone disease.

C. Caregiver views on the ways EOL care could be improved

Four themes identified need for (1) more personal contact from MND Association, (2) euthanasia option, (3) better preparation for EOL, and (4) health professionals needing to show more compassion and be trained appropriately.

Theme 1C: more personal contact and involvement from MND Association

A desire for more contact from the MND Association during the EOL period was reported. Respondents frequently noted a lack of contact during the palliative phase (‘Once palliative care were involved there was little or no support from MND Asoc’). Caregivers would have preferred more MND Association involvement and support during EOL (‘More checking in with the family to see how they are coping’; ‘A phone call, visit; basically a check-in to see how things were going. We didn’t see the advisor for 6 months before my husband died’; ‘The MND Assoc. seems incapable of intervening or ensuring the care is consistent and appropriate’). Minimal contact during the EOL phase was also perceived by respondents as lacking compassion (‘We virtually had none and when we saw someone was a rushed visit. No care factor’).

Theme 2C: euthanasia option

A strong theme was the request to have euthanasia as an option. Respondents emphasised their desire to see the law changed to allow the choice to end life via voluntary euthanasia or voluntary assisted dying (VAD) (‘Legal and social acceptance of voluntary euthanasia’). The rationale behind this request was evident in comments regarding the reduction of suffering (‘The end took too long – and seemed very distressing and terrifying to patient’; ‘It is distressing watching your mother die slowly. She wanted to die sooner but could not’) as well as dying with dignity (‘Allowing a person to die with dignity – VAD needs to be introduced’). Respondents perceived a lobbying for change role for MND Associations in this area (‘end of life was being managed with help from GP and palliative care. What MND Association could do would be to lobby for legal euthanasia’).

Theme 3C: better preparation for EOL

Many respondents felt unprepared for the EOL process and death. They expressed a need for education and guidance about what they can expect in the final stages of MND (‘Let the caregiver know what to expect. I didn’t understand what was happening I think they just expected me to know what was happening’; ‘Offering some form of awareness to those interested of what the final stages may be to help with end of life care’; ‘Explain what likely to happen as I feel I was unprepared for how and when my husband would pass away’). Respondents noted the negative emotional consequences associated with being unprepared for EOL (‘A main issue was a failure/unwillingness by the MND Clinic to inform me of how the “end might come”. This created a sense of fear in self and patient’; ‘Maybe be told the things that will happen in more detail so you’re not shocked when your loved one dies quicker than you thought’).

Theme 4C: health professionals needing to show more compassion and be trained appropriately

Areas of improvement were related to respondents’ experiences of a lack of compassion from health professionals during EOL. Respondents noted barriers through distressing experiences; with doctors (‘The palliative care doctor in charge would not set up the morphine pump, as had been discussed to relieve severe episodes of breathing distress’; ‘GP’s attitude towards prescription of pain medication, palliative care unit had to intervene’) and with nurses (‘MND palliative care nurse not helpful at all. An MND trained nurse to visit and support, we had one visit once in two weeks and only stayed for two minutes – shows no care or compassion’; ‘To have the staff in nursing home more educated on this illness, otherwise they show lack of care/kindness’). Caregivers reported a lack of training in rural and regional areas (‘Being regional there wasn’t much available. Nurses didn’t know how to care for an MND patient’).

D. Caregiver views on the ways to improve support during bereavement

Respondents commented specifically on the ways in which support during bereavement could be improved. Six themes were identified as follows: (1) more contact and compassion from MND Associations postdeath, (2) MND Association providing referrals and links for counseling, (3) access to caregiver support groups and peer interaction, (4) provision of a genuine continuum of care rather than postdeath abandonment, (5) guidance regarding postdeath practicalities and (6) more access to postbereavement support in rural and regional areas.

Theme 1D: more contact and compassion from MND Associations postdeath

A strong theme was respondents’ dissatisfaction with contact and compassion from MND Associations postdeath (‘Immediately after the death of my husband, I received a call that the MND Association was going to pick up the apparatus used– lack of compassion as it was 4 days post death’; ‘If they had kept in touch with myself after my husband had died – even if only for a short while’). A lack of bereavement support for caregivers was evaluated negatively (‘Bereavement support could have been useful . . . At end of life, it might have been useful to have someone ring to ask if it’s all OK’; ‘Once partner dies, a better follow-up than a typed letter’; ‘The final face to face session with the carer, it felt like, when my brother died, that their role had ended. It becomes more business’). Some respondents noted a sense of abandonment by the MND Associations postdeath (‘You should make contact with person after losing someone. I have not experienced this after my partner gone, like nothing happens, no one around you have to deal on your own’; ‘More care/visit for the person left behind’).

Theme 2D: MND Association providing referrals and links for counseling

Improvement of bereavement support included a request to be connected to counseling services. While some respondents reported a general need for counseling (‘Counselling. My life has changed, I no longer feel like I belong to general society’), others requested professional counseling (‘Psychologist/Counsellor with experience of MND. Weren’t able to access counselling from MND Assoc. – only from [another organisation]’; ‘Professional support’; ‘the caller - obviously a very caring person but I didn’t need someone who seemed as upset as I was. Skilled support is necessary’) and support groups (‘Contact and recommendations on support groups’). Numerous respondents reported wanting to be referred to, or linked with, counseling (‘MND Assoc. needs resources to assist more in this stage – such as referral to Psychologist, Counsellor etc’.; ‘I wonder if the MND Assoc. would recommend counsellors. I really did not know where to start looking’).

Theme 3D: access to caregiver support groups and peer interaction

Respondents requested and valued support from other MND caregivers. Where such support was absent, or had ceased, respondents noted their disappointment (‘The support group I attended for 5 1/2 years ceases to exist for the caregiver once the patient dies’; ‘During the illness it was difficult to attend support groups but after his passing I would have loved to meet up with past caregivers’; ‘I would like a previous caregiver of an MND patient visit the recently bereaved’). Where peer support was present, respondents noted the benefits of this support (‘A meeting for caregivers after death was excellent’; ‘I’m aware that for my father, the MND caregiver’s group were his main source of support as there were others who had been bereaved also’).

Theme 4D: provision of a genuine continuum of care rather than postdeath abandonment

Respondents perceived a need for a continuum of care that extends beyond the patient’s death. They expressed dissatisfaction with an abrupt end of support during bereavement (‘Some contact would have been appreciated;’ ‘I did not understand why [patient] left suddenly and we did not say “goodbye”’; ‘Basically once he had passed, heard nothing from them’), while others requested that care should continue beyond death (‘Follow up communication (phone call) in the months following bereavement would have been appreciated, especially prior to first Christmas’).

Respondents commented not only on the lack of contact via phone or visits (‘A few more visits to check how you are handling things and supply information about available help if needed. It is not easy in this situation to make a phone call and admit you need help’) but also on the quality of the contacts. Minimal, non-personal or non-compassionate contact from the MND Association postdeath was considered tokenism rather than genuine support (‘Receiving more than a card and referral to donate clothes and one home visit would have been appreciated’; ‘I received the follow up call and it was OK but felt superficial’). Respondents were also aware of the limited resources available to MND Associations and added their voices to the push for increased funding and resources (‘Follow up support. Want more contact, would have been helpful for those with no other support systems. I do understand the association is limited though’; ‘More funding for more staff in the community organisations’).

Theme 5D: guidance regarding postdeath practicalities

Guidance in the form of lists and information covering practicalities postdeath were suggested improvements, to assist caregivers to prepare and deal with bereavement (‘Perhaps a practical list of how to organise funeral, finances etc. (or a list) might help someone without knowledge in the past, to follow’; ‘Checklist booklet for things to consider and contacts’; ‘and timeline for things to be finalised. The days fly by when grieving and support on what needs to be taken care of would be very beneficial’).

Theme 6D: more access to postbereavement support in rural and regional areas

Lack of postbereavement MND services for people in rural and regional areas was of concern. Respondents emphasised the lack of support in these areas (‘More support after he passed away. There was ‘nowhere in [my] area to access support or none that I know of’; ‘programmes not accessible for regional dwellers’) and called for greater equity of access (‘People living in more remote areas should have the chance others get to support people. The MND Association needs to address this problem’).

Discussion

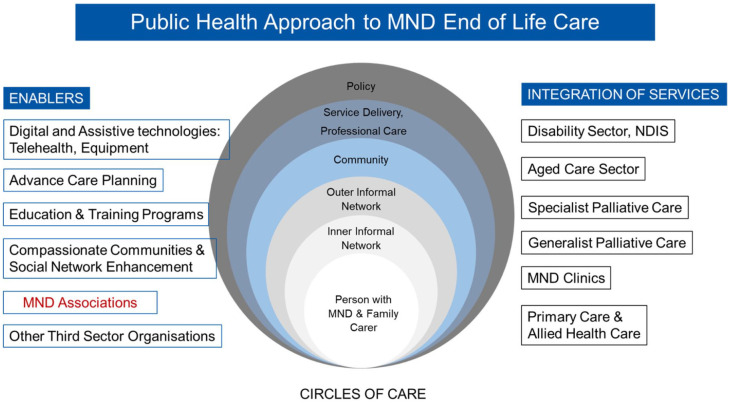

To our knowledge, this is the first study nationally or internationally to systematically investigate the EOL and bereavement experiences of MND family caregivers and what matters most to them, based on a relatively large number of respondents to a national survey. Evidence on what is working well and not so well has been sorely needed to position such third-sector organisations as effective partners with the community and enablers of the many sectors they navigate. To address this, the fourth objective of this study was to propose a model of care to meet the needs and preferences of consumers while supporting the capacity of MND Associations within a multidisciplinary care environment. This proposed model enables the navigation and integration of the many sectors of care through a person- or family-centred approach to care as a Public Health Approach to MND EOL care (Figure 1). MND associations provide support during the illness experience for PwMND and their families and are ideally placed to do so from diagnosis to EOL and bereavement. In this national survey, 97% of MND families have contacted their state-based associations, with the majority at time of diagnosis. In addition, these types of organisations can connect both professional and community resources in a way that clinicians alone, or community actors, cannot.7

Figure 1.

The position of MND Associations within the public health approach to MND EOL care.

Public health approaches to EOL care have potential to enhance integration of services and provide a comprehensive approach that engages the assets of local communities. Moreover, they offer frameworks in which partnerships can be developed with patient communities with distinctive EOL needs, such as those with noncancer conditions and thus provide a more inclusive approach to EOL care.17 To achieve this requires direct input from the consumers about their experiences of unmet needs and how these can be met with better partnerships between the health services and the community. This includes consumers involved in the co-design. EOL care systems, to be effective, must recognise the ‘patient and social network’ which has also been emphasised in the literature.18 The ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ circles of care, and neighbourhood supports are the main foundation of resilient networks caring for people at home,19,20 as with most cases of MND. However, EOL care systems must also ensure that professional care, service delivery and policy enhance the care provided by the person’s social network and the not-for-profit organisations, and this is applicable at the international level.

Therefore, what do MND Associations need so they become effective enablers in this proposed model of care?

MND Associations are reported to be doing fairly well when it comes to the provision of equipment, informational and practical support, liaison with other services on behalf of the clients and helping clients navigate the various systems of health and disability, the personal contact, being visited at home and the time dedicated to such visits and contacts. Nevertheless, more is needed by the caregivers.

Training for and provision of emotional support

Emotional support is not reported to be at the same sound level of benefit to caregivers, despite this being promoted as an important core function of MND Advisors5,14 and families preferred information and support from people who understood and knew about MND.21 Emotional support is important because depression and anxiety increase the risk of PGD.2 Emotional support is also necessary for MND caregivers because of their much higher risk of PGD than the general bereaved population and insufficient support for caregivers during the disease journey was a significant predictor to PGD.2 Support helps caregivers to move on,22 but this study showed that the support received was not optimal. This dissatisfaction was closely linked to the perception that staff lacked training and competence in this area of care, which was compounded by insufficient contact with Advisors. MND Advisors often start their role without a training programme that is based on evidence and without clear performance benchmarks. They are often recruited without the appropriate clinical practice backgrounds and with the newcomers shadowing those already on the job. What is required is a more standardised practice by MND Associations basing the frequency and nature of client visits on assessment of the disease trajectory and the distress felt by the family. This also requires a more standard national approach to training MND Advisors to improve equity of care.

Caregiver support needs

A high number of responses highlighted the vulnerability and loneliness felt by caregivers during caregiving. Regularly assessing and addressing the needs of caregivers has been mentioned in many policy documents around the world and the benefits demonstrated in studies.23,24 However, this has not been translated into practice, mainly because of the reluctance of services to embrace caregivers as also being their clients. Despite the clear benefits for family caregivers, very few services worldwide were successful in introducing comprehensive assessment of caregiver needs into routine practice: ‘While there is clear research evidence and positive policy ambitions to achieve comprehensive, person-centred assessment and support for caregivers, so far these remain as aspirations in practice delivery’.25 The MND Association in Western Australia is currently training Advisors on the use of the Carers’ Alert Thermometer26 and has incorporated this systematic focus on caregivers in the job description of Advisors. Even so, this has yet to be adopted as a national focus by MND Australia, as has working on a national approach to training staff in supporting family caregivers in their own right, as well as patients.

Bereavement support

That respondents felt more supported before rather than after bereavement is not surprising, as there are no effective bereavement support initiatives in Australian MND Associations, and in general, family caregivers feel abandoned postdeath of the person with MND. Caregivers need bereavement support beyond that provided by family and social networks.7 At a minimum, all Associations should be able to provide referrals linking the bereaved to grief counseling services where necessary and provide information leaflets on how to locate these services in their communities.

A second initiative is to train MND Advisors to pick up on cues of who is feeling distressed to advise on and initiate referrals, and set up a system where Advisors keep connecting with bereaved families for at least the first 6 months of bereavement, showing genuine interest, support and empathy and not a tokenistic gesture. Caregivers have an existing relationship with the MND Associations, which are positioned appropriately to be a provider or at least a conduit to bereavement services; that is, providing a genuine continuum of care.

There needs to be the option of online/telehealth services to address the rural lack of access to services as identified in this study, in addition to visiting services if the possibility of locating Advisors in regional areas is not an affordable option. That 38% of people have responded from rural areas, nearly twice as many as there are rural clients, underscore their cry for help to redress the equity of care. Several US studies have demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of using telehealth in the MND patient population, especially for those living away from clinics.27,28 Following COVID-19, MND clinics and MND Associations have stepped up telehealth initiatives for patient consultations. The Neurological Alliance Australia29 has called for the ‘Continuation of expanded Telehealth for all Australians – post COVID-19 pandemic response’. There is some evidence that telehealth delivered grief support groups for rural bereaved hospice families are also feasible and effective.30 An equitable, national approach to MND telehealth services which addresses the needs of patients and caregivers, especially those living in rural areas, and their health providers is indicated.

A further initiative is to organise support groups where bereaved caregivers can meet and share their common experiences. Peer social support has been one of the benefits appreciated by the survey respondents. These groups could be led initially by a professional in the field and then by trained volunteers from the community. There is some evidence that support groups can be beneficial,31 but this also depends on the goodness of fit between the needs of the bereaved and the response provided by such support groups.32 MND caregivers are at a higher risk of developing PGD than the general bereaved population and higher proportions are in the moderate risk where peer support and volunteer-led groups could be beneficial. It is at this level of risk that MND Associations can be most effective and make a difference.7

Moreover, MND Associations can better support caregivers through information leaflets on the process of funeral arrangements, who to contact and in dealing with other ‘postdeath practicalities’. This is especially helpful with the considerable number of MND deaths occurring at home: 34% in Western Australia and 25% in Victoria and New South Wales.5 Such information can be sourced from funeral companies but could also be easily accessible from MND Associations.

Partnerships with and training of general health professionals

While there is a notable perception expressed by respondents that the MND Associations lacked resources, particularly in terms of service funding, MND Associations need to look outwards and forge partnerships with a range of health professionals, who with adequate training in the MND area, can support the work of the Associations. Training primary care health professionals as well as those working in the aged care sector could be a core function of the associations. For example, to date and within 1 year, the MND Association in Western Australia has trained 321 health professionals in metropolitan and rural areas on how to support people with MND and their families, with overwhelmingly positive feedback from attendees.33 Research has shown that health and social care professionals involved in the care of people with MND feel unable to accurately predict which MND family caregivers may develop abnormal bereavement responses such as the PGD.34 Bereaved older adults usually seek bereavement support from primary care sources, but it is known that primary-care practitioners have deficits in this area and require training.35 In this study, 74% of MND caregivers accessed GPs for bereavement support although 34% found them unhelpful.7

Preparation for EOL

Caregivers noted the lack of contact of MND Advisors at EOL, the lack of effective and early palliative care and the need for Advisors to advocate more for palliative care particularly because, in most Australian states, specialist palliative care providers become involved at a late stage in MND care and a palliative approach to care is not well established.36 This lack of early and effective palliative and EOL care for MND may have been triggering the calls for VAD and caregivers clearly wanted to be able to discuss euthanasia/VAD as an option at EOL, and this may be whether they have access to specialist palliative care or not. VAD is now available in three Australian states: Victoria, legislated for in Western Australia with implementation due to start in July 20215 and recently legislated for in Tasmania.

Clear communication throughout the illness trajectory and including the development of advance care planning is central to good care and a good death.36–38 Due to fears about the dying process associated with MND, integrating advance care planning conversations and palliative care can optimise quality of life by relieving symptoms; providing emotional, psychological and spiritual support prebereavement; minimising barriers to a comfortable EOL; and supporting the family postbereavement.4,36 MND Associations can advocate for earlier and more timely involvement of palliative care services and advisors be trained to hold such conversations on planning ahead with their clients,36,39 including VAD wishes. While Box and colleagues, found that UK disability organisations were ambivalent, at best, about assisted dying, similarly in Australia, MND Australia, the peak body, provided a statement that their position is neutral and follows the legal status of each state and therefore ‘supports a person’s rights in all things that are lawful’.40,41

Respondents expressed feeling very unprepared for EOL and a need to be educated and guided by the MND Associations. Lack of preparedness may increase PGD risk as perceived preparedness for the death of the patient predicted better adjustment to bereavement, independent of other factors.42 Going through the process of advance care planning gives families the opportunity to be better prepared which in turn affects bereavement outcomes.43 Again, MND Associations can provide such education opportunities to consumers and general health professionals in partnerships with palliative care organisations in every state.

In relation to the interface with bereavement support by palliative care services, the feedback from an Australian population-based bereavement survey underlined the limited helpfulness of the blanket approach to bereavement support adopted by palliative care services, support often described by consumers as not personal, or generic, or just standard practice. Respondents still drew on their informal and community networks whether they did or did not use palliative care services.44 However, those who have used palliative care services during the disease journey were twice more like to have an advance care plan or advance health directive.44 Therefore, early involvement of palliative care services could help in advance care planning and preparedness.

Conclusion

By enacting the several improvements suggested by consumers, MND Associations have great potential to play a more effective role as an enabler in the public health approach to EOL model of care (Figure 1) and to be more relevant to the communities they serve at the national and international levels. This also applies to most third-sector organisations where their role needs to be bolstered alongside formal services. Currently, this potential is not achieved in Australia because of the lack of consistency of training and delivery of services across the states, primarily due to a lack of research investment in health and social care and service improvement, as distinct from from basic science and clinical research.6

Consumers need to be listened to and services should be responsive to their needs. Research seems to focus on using consumer feedback to improve service delivery, but not to involve consumers in changing service design or policy at the macro level.45 Given the paucity of data on consumer experience, and the selective and uneven contribution made by consumers to service and policy in EOL care, it is important that a strategy for receiving consistent and regular consumer feedback be introduced into the sector’s Continuous Quality Improvement processes.

A national approach is needed that encompasses uniformity, continuum of care incorporating EOL care and bereavement support, consumer feedback and representation in designing services, that can be linked to the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards and in particular Standard 2, Partnering with Consumers.46 This national approach is required to monitor consumer feedback as a basis for service planning, highlighting the gaps and providing meaningful policy advice to governments. Until such time when there is a cure or treatment for MND, there is an enormous amount of care that needs to be based on research evidence that is required to support PwMND and their families before and during bereavement.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: This work was financially supported by MND Research Australia-MSWA grant. The authors are grateful for the cooperation and assistance of the MND Associations and for the bereaved families who agreed to complete the survey, especially considering their difficult circumstances.

ORCID iDs: Samar M. Aoun  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-4805

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-4805

Paul A. Cafarella  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0165-4909

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0165-4909

Anne Hogden  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4317-7960

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4317-7960

Leanne Jiang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1729-9729

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1729-9729

Contributor Information

Samar M. Aoun, Public Health Palliative Care Unit, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia; Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, Perth, WA, Australia; Chair, MND Association in Western Australia, Carlisle, WA, Australia.

Paul A. Cafarella, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, SA, Australia; School of Psychology, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia; College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA, Australia

Anne Hogden, Australian Institute of Health Service Management, College of Business and Economics, University of Tasmania, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Geoff Thomas, Thomas MND Research Group, Adelaide, SA, Australia; Consumer Advocate and Chair; MND Association in South Australia, Mile End, SA, Australia.

Leanne Jiang, Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, Perth, WA, Australia; Public Health Palliative Care Unit, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Robert Edis, Department of Neurology, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, WA, Australia.

References

- 1. Harley K, Willis K. Living with motor neurone disease: an insider’s sociological perspective. Health Sociol Rev 2020; 29: 211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aoun SM, Kissane DW, Cafarella PA, et al. Grief, depression, and anxiety in bereaved caregivers of people with motor neurone disease: a population-based national study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2020; 21: 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hogden A, Paynter C, Hutchinson K. How can we improve patient-centered care of motor neuron disease? Neurodegener Dis Manag 2020; 10: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hogden A, Aoun SM, Silbert PL. Palliative care in neurology: integrating a palliative approach to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis care. Eur Med J 2018; 6: 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aoun S, Birks C, Hogden A, et al. Public policy in MND care: the Australian perspective. In: Blank RH, Kurent JE, Oliver D. (eds) Public policy in ALS/MND care. Berlin: Springer, 2021, pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aoun SM, Hogden A, Kho LK. ‘Until there is a cure, there is care’: a person-centered approach to supporting the wellbeing of people with motor neurone disease and their family carers. Eur J Person Cent Healthc 2018; 6: 320–328. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aoun SM, Cafarella PA, Rumbold B, et al. Who cares for the bereaved? A national survey of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease. Anyotroph La Scl Fr. Epub ahead of print 10 September 2020. DOI: 10.1080/21678421.2020.1813780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deloitte Access Economics. Economic analysis of motor neurone disease in Australia. Report for Motor Neurone Disease Australia, Deloitte Access Economics, Canberra, ACT, Australia, November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reed H, Langley J, Stanton A, et al. Head-up; an interdisciplinary, participatory and co-design process informing the development of a novel head and neck support for people living with progressive neck muscle weakness. J Med Eng Technol 2015; 39: 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maunsell R, Bloomfield S, Erridge C, et al. Developing a web-based patient decision aid for gastrostomy in motor neuron disease: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e032364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Russell-Westhead M, O’Brien N, Goff I, et al. Mixed methods study of a new model of care for chronic disease: co-design and sustainable implementation of group consultations into clinical practice. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2020; 4: rkaa003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aoun SM, Deas K, Kristjanson LJ, et al. Identifying and addressing the support needs of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease using the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Palliat Support Care 2017; 15: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foley G, Timonen V, Hardiman O. Patients’ perceptions of services and preferences for care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012; 13: 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bodley L. ‘Walk with me’: reflections from a motor neurone disease care advisor. Eur J Person Cent Healthc 2019; 7: 466–469. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Health. Towards a health navigation strategy for long term neurological conditions: a discussion paper. Perth, WA, Australia: Department of Health, Western Australia, 2018, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aoun SM, Abel J, Rumbold B, et al. The Compassionate Communities Connectors model for end-of-life care: a community and health service partnership in Western Australia. Palliat Care Soc Pract. Epub ahead of print 1 January 2020. DOI: 10.1177/2632352420935130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris M, Thomas G, Thomas M, et al. Supporting wellbeing in motor neurone disease for patients, carers, social networks, and health professionals: a scoping review and synthesis. Palliat Support Care 2018; 16: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horsfall D, Leonard R, Noonan K, et al. Working together-apart: what role do formal palliative support networks play in establishing, supporting and maintaining informal caring networks for people dying at home. Prog Palliat Care 2013; 21: 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foley G, Timonen V, Hardiman O. Understanding psycho-social processes underpinning engagement with services in motor neurone disease: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burns E, Prigerson HG, Quinn SJ, et al. Moving on: factors associated with caregivers’ bereavement adjustment using a random population-based face-to-face survey. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Toye C, Parsons R, Slatyer S, et al. Outcomes for family carers of a nurse-delivered hospital discharge intervention for older people (the Further Enabling Care at Home Program): single blind randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 64: 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aoun SM, Grande G, Howting D, et al. The impact of the carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) in community palliative care using a stepped wedge cluster trial. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0123012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ewing G, Grande G. Providing comprehensive, person-centred assessment and support for family carers towards the end of life: 10 recommendations for achieving organisational change. London: Hospice UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Knighting K, O’Brien MR, Roe B, et al. Development of the Carers’ Alert Thermometer (CAT) to identify family carers struggling with caring for someone dying at home: a mixed method consensus study. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haulman A, Geronimo A, Chahwala A, et al. The use of telehealth to enhance care in ALS and other neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve 2020; 61: 682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geronimo A, Wright C, Morris A, et al. Incorporation of telehealth into a multidisciplinary ALS Clinic: feasibility and acceptability. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2017; 18: 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neurological Alliance Australia. Continuation of expanded Telehealth for all Australians – post COVID-19 pandemic response, 2020, https://m.mndaust.asn.au/Documents/NAA-Position-Statement-Expanded-Telehealth-FINAL-2.aspx

- 30. Supiano KP, Koric A, Iacob E. Extending our reach: telehealth delivered grief support groups for rural hospice. Soc Work Groups 2021; 44: 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cipolletta S, Gammino GR, Francescon P, et al. Mutual support groups for family caregivers of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Italy: a pilot study. Health Soc Care Community 2018; 26: 556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Rumbold B, et al. Matching response to need: what makes social networks fit for providing bereavement support. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0213367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Motor Neurone Disease Association of Western Australia, 2021, https://www.mndawa.asn.au/

- 34. O’Brien MR, Kirkcaldy AJ, Knighting K, et al. Bereavement support and prolonged grief disorder among carers of people with motor neurone disease. Br J Neurosci Nurs 2016; 12: 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ghesquiere AR, Patel SR, Kaplan DB, et al. Primary care providers’ bereavement care practices: recommendations for research directions. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 29: 1221–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aoun SM. The palliative approach to caring for motor neurone disease: from diagnosis to bereavement. Eur J Person Cent Healthc 2018; 6: 675–684. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Breen LJ, Kawashima D, Joy K, et al. Grief literacy: a call to action for compassionate communities. Death Stud. Epub ahead of print 19 March 2020. DOI: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1739780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mandler RN, Anderson FA, Jr, Miller RG, et al. The ALS Patient Care Database: insights into end-of-life care in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2001; 2: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheng HWB, Chan OMI, Chan CHR, et al. End-of-life characteristics and palliative care provision for patients with motor neuron disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018; 35: 847–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Box G, Chambaere K. Views of disability rights organisations on assisted dying legislation in England, Wales and Scotland: an analysis of position statements. J Med Ethics. Epub ahead of print 5 January 2021. DOI: 10.1136/medethics-2020-107021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Motor Neurone Disease Association of Australia. Rights and responsibilities of people living with motor neurone disease (MND): position statement, 2017, https://m.mndaust.asn.au/About-us/Policies-and-position-statement/National-policies-and-position-statements/POLICY-STATEMENT-NUMBER-6-Rights-and-Responsbiliti.aspx

- 42. Kim Y, Carver CS, Spiegel D, et al. Role of family caregivers’ self-perceived preparedness for the death of the cancer patient in long-term adjustment to bereavement. Psycho-Oncology 2017; 26: 484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aoun SM, Ewing G, Grande G, et al. The impact of supporting family caregivers before bereavement on outcomes after bereavement: adequacy of end-of-life support and achievement of preferred place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55: 368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aoun SM, Rumbold B, Howting D, et al. Bereavement support for family caregivers: the gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0184750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hall AE, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher RW, et al. Consumer input into health care: time for a new active and comprehensive model of consumer involvement. Health Expect 2018; 21: 707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National safety and quality health service standards. 2nd ed. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; (ACSQHC), 2017. [Google Scholar]