Summary:

Fifty-six percent of high-needs NYC cancer patients are food insecure, at times choosing between medical treatment and food. We describe FOOD (Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities), an innovative intervention, which has established eleven medically tailored food pantries in NYC cancer centers and distributed the equivalent of 307,080 meals since 2011.

Keywords: Food insecurity, cancer patients, food bank, pantry, nutrition, financial toxicity, non-adherence, quality of life, treatment, intervention, hunger, immigrant, minority

Introduction

Food insecurity, lacking consistent access to sufficient food for an active and healthy lifestyle,1 affects many underserved cancer patients, who may have to choose between treatment and food.2 In a study of low-income, high-needs, predominantly immigrant and minority New York City (NYC) cancer patients, 56% were food insecure—more than three times the national and nearly five times the state averages.2 Food-insecure cancer patients have poorer quality of life and lower rates of treatment completion than cancer patients in general and face additional risk from the effects of compromised nutrition.3–5

Although the Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provided benefits to 40.4 million people in 2018, it reached only 41.2% of food-insecure households. There are various reasons for this, including because some are above the income eligibility cutoff but are still food insecure and also because of immigration status eligibility restrictions.1 Year 2013 SNAP cuts have resulted in an average loss nationally of $36/month per household of four and a loss of over $1 billion in benefits for NYC alone—equivalent to 283 million meals.6, 7 Nationally, the cuts have contributed to a 14% rise in the prevalence of very low food security among SNAP recipients.7 Subsequently, community-based emergency food resources have faced increased demand: 80% of NYC food banks and soup kitchens have seen elevated visitor traffic and 54% have reported running out of food since the SNAP cuts.6 Furthermore, the financial strain experienced by cancer patients, who have many treatment-related costs, are not considered in the SNAP benefit calculations, potentially rendering SNAP inadequate to meet even eligible patients’ needs.

Emergency food resources provide crucial relief to just 29.3% of US food-insecure households,1 and they are not generally structured to meet the special needs of food-insecure cancer patients.4 For example, they often do not have medically tailored food and they have limited opening hours, coincident with clinic hours, precluding their use by patients whose treatment necessitates many appointments.4 Additionally, they do not meet the language needs of many immigrant cancer patients, and may have identification requirements that exclude immigrants without status.8

These overextended emergency food resources are often insufficient for low-income cancer patients in urgent need of medically tailored nutrition. Although there are some hospitals throughout the US that host food pantries,9 the numbers are small, and these are generally not tailored towards cancer patients. Food security and fruit and vegetable intake improvements are reported with food pantry interventions that include nutrition education elements,10 which could also help to tackle the generally poor American diet quality. High quality evaluation of food-insecurity interventions in healthcare settings is lacking.11 To address food-insecure patients’ pressing needs, the Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service (IHCD) initiated FOOD (Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities), a first-of-its-kind program to co-locate medically tailored food pantries in targeted NYC cancer clinics. The objectives were to create and implement an expandable, sustainable, evaluable medically tailored FOOD pantry infrastructure, incorporating cancer patient-tailored nutrition education, to help meet patients’ nutritional needs, thereby improving treatment adherence and outcomes.

Model Elements

The first FOOD pantry opened as a pilot in 2011 in a NYC cancer center where IHCD conducted patient navigation. Ten additional NYC pantries have since opened, serving predominantly immigrant, food-insecure cancer patients.

Staff and administrator support.

Administrative support, collaboration with important stakeholders, such as clinic directors and staff, social workers, and nutritionists, is critical to ensure medially tailored food pantry success. Administrator concerns have included pantry staffing, food-safety regulation compliance, and space requirements. In this model, we allay these concerns with our food-safety trained and certified staff and creative solutions to space issues (described below). Other approaches could include training clinic staff on food-safety compliance.

Not all hospital staff are aware of the prevalence of food insecurity among patients. One hospital, for example, requested a snapshot survey to ascertain whether our program was needed. Of 100 patients, 83% reported needing assistance with buying groceries, and 66% reported having less money for food since diagnosis. Because of these results, that hospital authorized the pantry and has lent us unstinting support.

Patient need and referral.

To help hospital staff understand food insecurity and its impact on cancer patients, IHCD has created a provider training module, with best practices for risk assessment. Approximately 25% of safety net cancer clinic patients are referred to FOOD by clinicians, social workers, clinic staff, and other patients, and approximately 80% of these screened as food insecure. Additionally, IHCD staff sensitively and discretely reach out to patients in waiting areas to inquire about their food needs: 60% of these patients who join the pantry screen as food insecure.

A needs assessment is administered to new FOOD patients, with validated instruments to measure food insecurity, nutrition, and quality of life, such as the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Household Food Security Survey,12 Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment,13 and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General.14 We use a 30-day timeframe with the USDA survey to capture food insecurity since cancer diagnosis/treatment began, and administer it monthly to evaluate the FOOD intervention impact.12 This survey establishes initial pantry eligibility and helps us to track FOOD’s impact on patients’ food security status. Regardless of results, we assure patients that they will get pantry food throughout treatment, for as long as they say they need it.

Space.

With limited clinic space available, we have been flexible about pantry space configuration, while meeting minimum requirements. There must be lockable food storage and a room to meet patients privately, without interrupting clinic flow. Creative space limitation solutions include meeting patients and distributing food in the cancer center while storing food on a different floor, meeting patients in a conference room with cabinetry for storing food, and ordering food for same-day distribution because of limited storage.

Staffing.

A pantry can be operated by one to two IHCD staff members, depending on pantry volume; ancillary personnel, such as interns, help when available. Staff are food-safety trained and certified by an emergency food distributor, and can speak at least one language in addition to English, including Spanish, Mandarin, Bengali, French, and Arabic; supplementary medical interpretation services are also available. Each pantry location is open one morning per week during high patient-volume hours, although this service is unable to meet all patients’ needs. Staff activities include purchasing food, collecting it from emergency distributors, sorting it, and transporting it to the sites. They conduct patient outreach, education, and intake; food distribution; inventory tracking; patient preference monitoring to adapt inventory, and food maintenance and safety, and they record patient demographic and program usage data electronically.

Pantry food.

A large urban emergency food resource distributor is a vital partner, connecting us with local emergency food distributors to supply food to our nearest pantries. Half are supplied this way. We cannot rely solely on them because of limited control over food item selection and competing demand from providers’ community clients. Therefore, we supplement with purchases of items lacking from our inventory, donations from food companies, and food drives for specific items. Cash donations from charitable foundations, individual donors, businesses, and fundraisers help maintain food supply and selection.

Each FOOD patient chooses food item to comprise approximately nine meals/week, and nutritionist input ensures that the available foods meet patients’ nutritional needs. Each FOOD patient chooses one bag of food/week, equivalent to nine meals, and nutritionist input ensures that the available foods meet patients’ nutritional needs. For food-safety reasons, stored food must be shelf stable. We maximize its nutritional value by including shelf-stable milks; unsweetened dried and canned fruits; grains (preferably whole); and low-sodium canned vegetables, beans, lean proteins, and soups. Weekly patient feedback helps us to tailor bag contents and has led us to include foods, such as dried beans, that are highly desirable among people from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Fresh produce is often requested by patients, but we do not have refrigerated storage for it. Therefore, at three sites, we have worked together with community-based agricultural organizations that can supply fresh produce for same-day pantry distribution (Figure 1). We also leverage the NYC Health Bucks program, which provides two-dollar coupons from July through November that patients can spend at NYC farmers markets (see Patient education, below). The patient response to fresh produce has been overwhelmingly positive, and our goal is to forge further partnerships so that we can supply it to all our patients, year-round.

Figure 1. Fresh produce enhances the nutritional value of pantry food.

Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service staff and interns are pictured at the pantries. Partnering with community-based agricultural organizations has enabled FOOD (Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities) to acquire healthy fresh produce for cancer patients.

Patient education.

The FOOD program cannot meet all of our patients’ nutritional needs or provide them with food after treatment completion. Therefore, we educate patients on, and connect them with, other sources of food and/or food funding for which they may be eligible. Outreach staff help patients determine their eligibility for SNAP, explaining the application process and assisting them in submitting online applications. This saves time-pressed and treatment-weary patients trips to the SNAP administrative offices or the stress of completing the online application alone.

Outreach staff educate patients about other food services that are available in their communities, including cancer patient meal delivery programs and emergency food resources available in their neighborhoods. We show patients how to apply for Health Bucks outside our program, which are doubled in value for SNAP recipients. We take patients to farmers’ markets adjacent to the hospitals to demonstrate using Health Bucks and the nutritious foods on offer, an activity that FOOD patients particularly enjoy and appreciate.

We worked with a nutritionist to develop an English/Spanish language nutrition education curriculum for food insecure cancer patients. We then drew upon existing literature and patient informant interviews to iteratively refine the curriculum. It is offered to FOOD patients and includes guidance on food choices and portioning, food choices to address side effects, food safety, and dollar-stretching tips.

Funding and support.

Fundraising and partnerships with emergency food resource distributors, community-based agriculture, hospital administrators and clinicians, the municipal hospital system, foundations, and local government have been key to the sustainability of this expanding program. We continuously search for grants that support our mission, and we work with our institution’s Development Office to connect with additional funders. We hope to use our results to encourage ongoing policy support of initiatives such as FOOD, leading to greater funding allocations for supplementary food resources that are tailored to underserved patients with cancer and other chronic conditions.

Impact

Our goal was to implement a much-needed strategy targeting food insecurity among cancer patients by creating food pantries co-located in cancer centers. Subsequently, we built the country’s first-ever cancer center-based pantry network, which has served the equivalent of 307,080 meals to 3,860 unique patients and 7,720 family members from January 2012 through December 2019. Most of our patients (70%) report having no income, almost half (47%) are non-Hispanic Black, 79% are foreign-born, 29% speak English not well or not at all, and the most common diagnosis is breast cancer (39%) (Table 1). FOOD evaluation studies include a 3-arm randomized controlled trial comparing treatment adherence, quality of life, food security, and diet quality across three food-insecurity interventions: clinic-based pantries, food vouchers, and meal delivery. A separate study assesses patient satisfaction and pantry uptake.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients seen at FOOD (Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities) pantries in New York City hospitals from January 2012 through December 2018

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Race (n=2091)† | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 992 (47) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 706 (34) |

| Asian | 235 (11) |

| White | 158 (8) |

| Born outside US (n=1936) | 1531 (79) |

| English spoken (n=2063) | |

| Very well | 1224 (59) |

| Well | 252 (12) |

| Not well | 333 (17) |

| Not at all | 254 (12) |

| Education (n=2033) | |

| No education | 38 (2) |

| Less than a high school degree | 849 (42) |

| High school degree | 659 (32) |

| Some college | 217 (10) |

| College or post-graduate degree | 281 (14) |

| Cancer diagnosis (n=2864) | |

| Breast | 1132 (39) |

| Prostate | 273 (10) |

| Gynecologic (cervical, uterine, ovarian, endometrial) | 272 (10) |

| Colon | 173 (6) |

| Lung | 197 (7) |

| Liquid tumors (leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma) | 179 (6) |

| Other | 637 (22) |

| Monthly Income (n=1856) | |

| $0 | 1301(70) |

| $1–$1,000 | 300 (16) |

| >$1,000 | 255 (14) |

Sample size for each category is shown. The intake survey was developed iteratively, and the sample size for each category varies accordingly.

Beyond the statistics, it is the words and experiences of our patients that demonstrate FOOD’s impact. One patient told us, “I used to borrow money for food. The pantry has been a blessing.” A patient we met in a clinic waiting area had broken open his child’s piggy bank to find the bus fare to get to his appointment and had no food for himself or his family. Our program helped the patient and his family to reliably access food during his cancer treatment.

Conclusions

Hospital-based food pantries provide food relief for underserved cancer patients who experience barriers to accessing emergency food resources and may otherwise delay or forgo treatment because of cost. With cancer-specific nutritious foods and guidance and tailored multilingual case-management services, low-income cancer patients can access the food they need during treatment and beyond. Forging strong partnerships opens resources in terms of infrastructure (including pantry space) and food (including fresh produce) and contributes to FOOD’s overall sustainability.

Our hospital-based pantry model is reproducible, allowing us to open eleven locations over eight years, and can provide the medically ill with temporary but necessary relief from food insecurity. Sixty-six percent of US food bank clients choose between food and medication or medical care, and interest in hospital-based food pantries is growing nationally.9 We hope that FOOD can provide an implementation model.

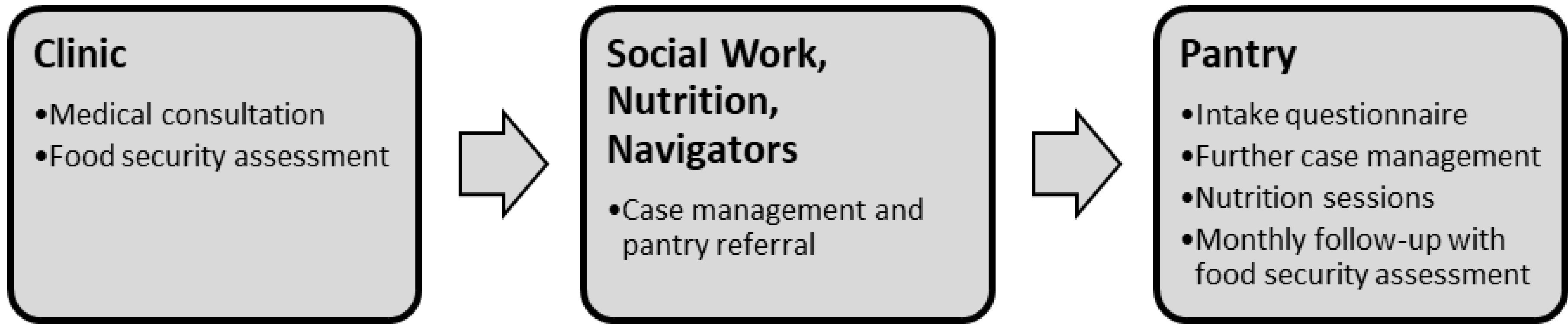

Figure 2. Patient flow, from consultation to pantry intake.

The Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service has created a data capture system to streamline the visit process. This system contains the visit log, case management notes, food preferences, and the intake questionnaire. The food security assessment used is the USDA US Household Food Security Survey Module.

Acknowledgments

A program like this cannot be implemented, grown, and sustained without the tremendous dedication of our staff and partners. The pantry’s development and continued efforts were funded by New York Community Trust, the City College of New York-Memorial Sloan Kettering Partnership for Cancer Research, Training, and Community Outreach (U54CA137788), the Avon Foundation, and the Laurie Tisch Illumination Fund. The pantry would not be possible without support from the Food Bank for New York City, Catholic Charities of Brooklyn and Queens, Bronx Citadel Salvation Army, St. Ann’s Episcopal Church, Triumphant Full Gospel Assembly Inc., Common Pantry, GrowNYC, Green Bronx Machine, and New York City Health + Hospitals. We would like to thank former staff members Thelma McNish, Josh Wessler, Aparna Balakrishnan, and Serena Phillips for their invaluable contributions to the development of FOOD and all FOOD staff for their tireless commitment to our patients.

Editorial support:

The authors would like to thank Sonya J. Smyk, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, for editorial support. She was not compensated beyond her regular salary.

Abbreviations:

- FOOD

Food to Overcome Outcomes Disparities

- IHCD

Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities

- NYC

New York City

- SNAP

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, et al. Statistical Supplement to Household Food Security in the United States in 2017. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2018AP-079.

- 2.Gany F, Lee T, Ramirez J, et al. Do our patients have enough to eat?: Food insecurity among urban low-income cancer patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014. August;25(3): 1153–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gany F, Leng J, Ramirez J, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Food-Insecure Ethnic Minority Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015. September;11(5):396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costas-Muniz R, Leng J, Aragones A, et al. Association of socioeconomic and practical unmet needs with self-reported nonadherence to cancer treatment appointments in low-income Latino and Black cancer patients. Ethn Health. 2016;21(2): 118–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010. February; 140(2): 304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food Bank for New York City. Hunger Cannot Afford to be Hidden: The Impacts of Bad Policies. New York, NY: Food Bank for New York City, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katare B, Kim J. Effects of the 2013 SNAP Benefit Cut on Food Security. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2017;39(4):662–81. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gany F, Bari S, Crist M, et al. Food insecurity: limitations of emergency food resources for our patients. J Urban Health. 2013. June;90(3):552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Care Without Harm. Program: Food banks and pantries,Hospitals and food banks partner to increase access to healthy food. Reston, Virginia: Health Care Without Harm, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.An R, Wang J, Liu J, et al. A systematic review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019. June;22(9): 1704–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Marchis EH, Torres JM, Benesch T, et al. Interventions Addressing Food Insecurity in Health Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Ann Fam Med. 2019. September;17(5):436–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research. US Household Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, With Screeners. US Department of Agriculture, 2012. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jager-Wittenaar H, Ottery FD. Assessing nutritional status in cancer: role of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017. September;20(5):322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celia DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993. March; 11(3): 570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]