Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Physicians increasingly share ambulatory visit notes with patients to meet new federal requirements, and evidence suggests patient experiences improve without overburdening physicians. Whether sharing inpatient notes with parents of hospitalized children yields similar outcomes is unknown. In this pilot study, we evaluated parent and physician perceptions of sharing notes with parents during hospitalization.

METHODS:

Parents of children aged <12 years admitted to a hospitalist service at a tertiary children’s hospital in April 2019 were offered real-time access to their child’s admission and daily progress notes on a bedside inpatient portal (MyChart Bedside). Upon discharge, ambulatory OpenNotes survey items assessed parent and physician (attendings and interns) perceptions of note sharing.

RESULTS:

In all, 25 parents and their children’s discharging attending and intern physicians participated. Parents agreed that the information in notes was useful and helped them remember their child’s care plan (100%), prepare for rounds (96%), and feel in control (91%). Although many physicians (34%) expressed concern that notes would confuse parents, no parent reported that notes were confusing. Some physicians perceived that they spent more time writing and/or editing notes (28%) or that their job was more difficult (15%). Satisfaction with sharing was highest among parents (100%), followed by attendings (81%) and interns (35%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Parents all valued having access to physicians’ notes during their child’s hospital stay; however, some physicians remained concerned about the potential negative consequences of sharing. Comparative effectiveness studies are needed to evaluate the effect of note sharing on outcomes for hospitalized children, families, and staff.

Participatory care, in which patients and caregivers are empowered with information and invited to engage in their health care,1 is deemed essential to ensuring high-quality care2–5 and patient safety.6,7 Innovations to improve information transparency, such as patient electronic health record portals,8–11 are rapidly expanding across health care organizations. Accelerated by positive findings from the OpenNotes literature,12–14 physicians’ notes are now readily accessible to many outpatients through patient portals, and note sharing will soon be required across hospital systems in accordance with the 21st Century Cures Act.15

Although the benefits of sharing physicians’ notes with adult patients have been well-described, whether similar benefits await parents when notes are shared during their child’s hospitalization remains unknown. Initial studies highlight the potential for notes to provide adult inpatients with the additional information and clarity necessary to make more informed decisions16–19 and inspire positive health changes.1,16–21 However, some physicians worry that these benefits may not translate to pediatrics given the added complexities of child-caregiver-physician dynamics, maintaining confidentiality, and the necessary protection of children.21 As hospitals gain the ability to share notes at the bedside,9 research is needed to understand the effects of sharing on parents and physicians.

Our objective was to evaluate parent and physician perceptions of sharing physicians’ notes with parents during their child’s hospitalization using a bedside inpatient portal. Findings from this pilot study will inform implementation efforts as hospitals work to comply with regulations mandating note sharing.15

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was conducted with physicians and parents of children admitted to a hospitalist service at a 111-bed Midwest tertiary children’s hospital from April to August 2019. On this service, pediatric interns write all admission and progress notes using standard note templates. Enrolled parents could view these notes on a bedside inpatient portal (MyChart Bedside; Epic Systems Corporation, Madison, WI) immediately after hospitalist attending editing and cosignature. The portal has been used at this hospital since 2014 and is provided to each family on a hospital-owned tablet (Apple iPad 32 GB; Apple Inc, Cupertino, CA) to use throughout their stay. The portal retained previously described functions22,23; however, note sharing was enabled for this study. No specific education was provided to physicians before sharing. Notes written by students, nurses, consultants, and other staff were not shared.

Participants and Recruitment

Purposeful sampling24 was used to recruit a diverse group of English-speaking parents or legal guardians of children aged <12 years with an anticipated length of stay of >24 hours. Parents of children aged ≥12 years were not included because of legal differences in access to confidential adolescent health information. Parents of children admitted with concerns of abuse or neglect were excluded. Eligibility was determined by chart review and confirmed with the attending. Physicians were eligible if they were the assigned intern or attending on the day of discharge. All physicians retained the ability to prevent any note from being shared. The institutional review board approved this study.

On admission, 1 parent from each child was invited to participate on the basis of family preference and anticipated availability after discharge. Researchers explained the risks and benefits of the study and obtained written informed consent. Note sharing was enabled, and parents were instructed on how to find notes once available. Parents were advised that 1 note would be available per day, typically by the late evening or following morning, and that questions could be addressed during morning rounds. Progress notes were not generally written on the day of discharge, nor were discharge summaries shared. There was no notification system in place to alert parents of note availability.

Data Collection and Analysis

On enrollment, validated survey items were used to assess parent and child demographics, previous Internet and portal use, and health literacy.25–27 After discharge, OpenNotes survey items previously employed in the adult ambulatory setting28 were used to evaluate parent perceptions of note sharing, including satisfaction with notes and whether notes were useful and helped them remember their child’s care plan, understand their child’s health, and feel more in control. An item developed for this study was used to assess whether notes improved parents’ ability to prepare for rounds.

The same items were used to assess intern and attending perspectives of note sharing. Additional OpenNotes items28 were used to assess physicians’ perceptions of the effect of sharing on their workload and job difficulty. Two items developed for this study were used to assess whether physicians perceived that sharing affected the length of rounds and number of questions parents asked outside of rounds. The physician survey also contained 3 open-ended questions regarding what they liked and disliked about note sharing and suggestions for improvement.

All enrolled parents who accessed ≥1 note and completed the discharge survey and their discharging interns and attendings were included in the analysis. Items were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”; responses were tabulated, and χ2 testing was used to compare groups. Two researchers performed inductive content analysis29 of physician open-ended responses, independently coding text using an iteratively refined codebook. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus with a third researcher.

Results

Of 32 eligible parents, 29 were enrolled and 25 were included in the analysis; 3 declined participation, 2 were discharged before note release, and 2 were unavailable to complete the discharge survey. Most parent participants were women (76%) and aged >30 years (72%) (Table 1). Parents had a wide range of race and/or ethnicity and education, income, and health literacy levels. Their children were hospitalized for a variety of reasons and had a median length of stay of 2 days (range, 1–18). Most parents (82%) reported reading notes >2 times daily. All physicians completed a discharge survey; none withheld a note from a parent.

TABLE 1.

Parent and Child Characteristics

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Parent, n = 25 | |

| Age, y | |

| 18–29 | 7 (28) |

| 30–39 | 12 (48) |

| >39 | 6 (24) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 19 (76) |

| Race and/or ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 15 (60) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3 (12) |

| Hispanic | 4 (16) |

| Other | 3 (12) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school graduate, GED, or less | 4 (16) |

| Some college, associate degree, or technical college | 13 (52) |

| College degree | 4 (16) |

| Higher than a college degree | 4 (16) |

| Annual household income, $USD | |

| <20 000 | 3 (12) |

| 20 000–59 999 | 7 (28) |

| 60 000–99 999 | 5 (20) |

| >99 999 | 9 (36) |

| Do not wish to answer | 1 (4) |

| Health literacya | |

| Limited, marginal, or inadequate | 12 (48) |

| Adequate | 13 (52) |

| Child, n = 25 | |

| Age, y | |

| <1 | 10 (40) |

| 2–5 | 4 (16) |

| 6–11 | 11 (44) |

| General health | |

| Excellent or very good | 10 (40) |

| Good | 8 (32) |

| Fair or poor | 7 (28) |

| Previous hospitalizationsb | |

| 1 | 10 (40) |

| 2 | 6 (24) |

| >2 | 9 (36) |

| Reason for hospitalizationc | |

| Fever | 8 (32) |

| Breathing problem | 6 (24) |

| Stomach and/or gastrointestinal problem | 4 (16) |

| Seizure and/or headache | 3 (12) |

| Kidney and/or urinary tract infection | 3 (12) |

| Other | 15 (60) |

GED, general education development test.

Limited, marginal, or inadequate health literacy determined by score on the Brief Health Literacy and Newest Vital Sign Screening Tools.28–30

Number of hospitalizations, including current but not birth hospitalization.

Multiple response choices allowed. Examples of other include failure to thrive, dehydration, skin problem, joint infection, and pain.

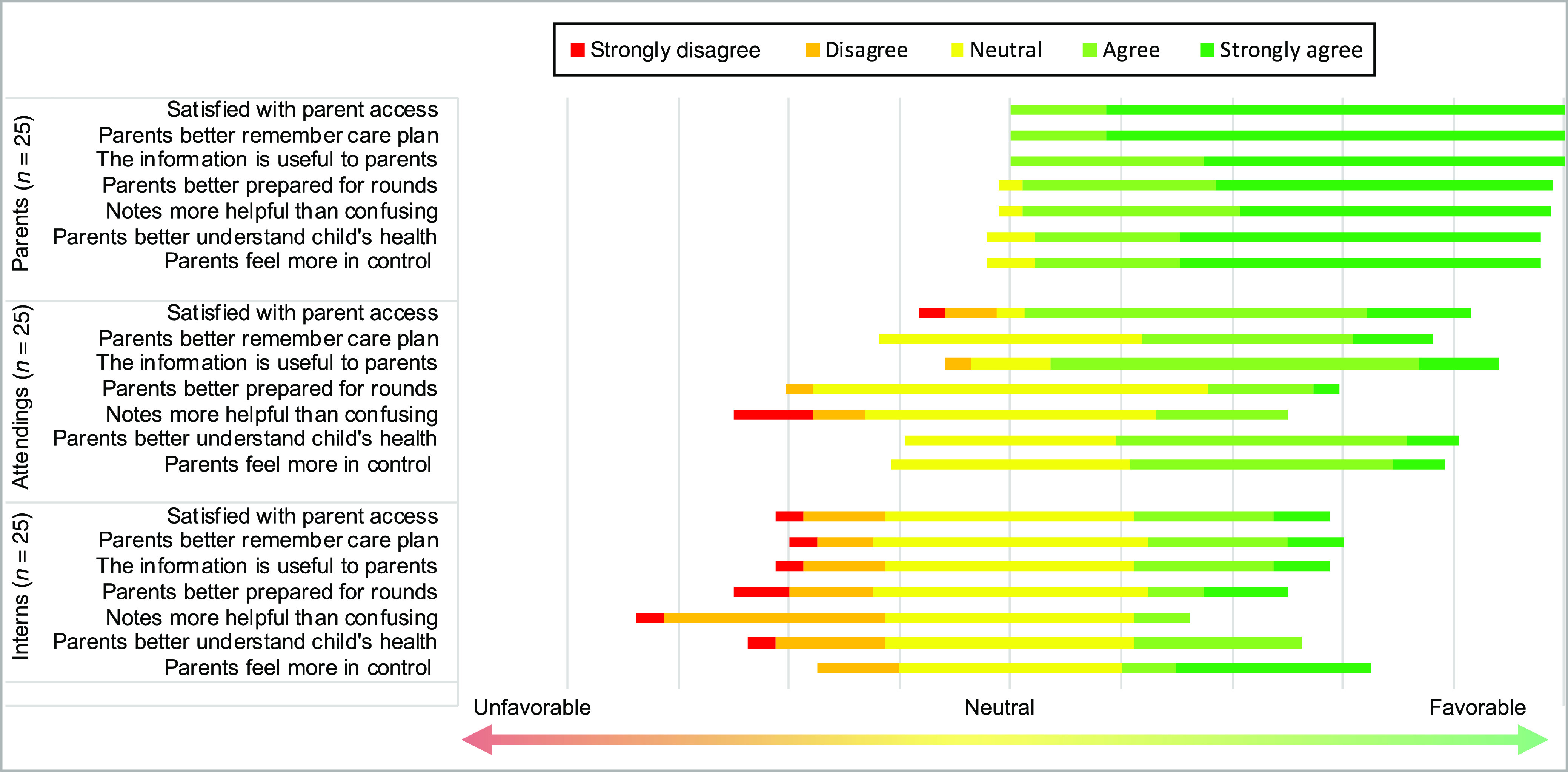

Favorability toward note sharing varied among parents, attendings and interns (Fig 1). All parents were satisfied with access and perceived that the information was useful and helped them remember their child’s care plan. Most agreed that notes helped them prepare for rounds (96%), understand their child’s health (91%), and feel more in control (91%).

FIGURE 1.

Parent, attending, and intern perceptions of the benefits of parent access to inpatient physicians’ notes (original prompt of “notes more confusing than helpful” and its associated data were inverted to “notes more helpful than confusing” for thematic representation).

Attendings generally responded more favorably to the benefits of notes than interns. Attendings were more satisfied than interns with parental access (81% vs 35%, respectively; P < .01). Although some physicians worried that their notes would cause confusion (24% attendings and 45% interns; P = .12), no parents agreed that notes were more confusing than helpful.

Regarding physician workload, some reported spending more time writing, dictating, and/or editing notes (30% attendings and 27% interns). Fewer were less candid in documentation (15% attendings and 19% interns) or changed note content regarding cancer, mental health, substance abuse, obesity, or child neglect and/or abuse concerns (11% attendings and 15% interns). Two interns, but no attendings, perceived that rounds took longer; only 1 intern reported answering more parent questions outside of rounds. Most physicians (81% attendings and 80% interns) indicated that sharing did not make their jobs more difficult.

Table 2 outlines physician perceptions of the benefits and downsides of sharing and suggestions for improvement. In all, 28% of physicians reported little or no feedback from parents about notes.

TABLE 2.

Physician Perceptions of the Benefits and Downsides of Note Sharing and Suggestions for Improvement

| Exemplary Physician Response | |

|---|---|

| Benefits | |

| Increased transparency | “It felt to me like a way of being completely transparent in a setting where people occasionally feel distant of a system they don't understand.” (Attending) |

| Improved documentation | “It caused both the resident and I to be more thoughtful about our documentation.” (Attending) |

| Reassurance or validation of concerns for parents | “[I] hope that parents feel reassured/validated - at least with the subjective [part of note] well documented.” (Intern) |

| Enhanced care plan clarity for parents | “There were multiple consultants involved … [It] was good to feel like even if [the parents] got different messages from teams, they could refer to [the note] if clarity was needed.” (Attending) |

| Downsides | |

| Limited documentation of sensitive topics, differential diagnoses, and/or information not yet discussed with parents | “I felt much more hesitant to discuss a broad differential in my note, as well as I was more cautious in how I phrased things.” (Intern) |

| “I did not include a differential diagnosis for a secondary, non-hospital problem because I had not yet had a chance to discuss it with the family. Not including this could impair my communication to the care team.” (Attending) | |

| Increased workload and/or time writing notes | “Increased workload - I spent more time editing the resident’s note... It was a very busy day, and I would not have invested that time for organizational issues (not content errors) otherwise.” (Attending) |

| Worry that notes will cause confusion for families | “[I] worry [the] family will be more confused.” (Intern) |

| Increasing physician stress and/or anxiety | “The right thing to do but anxiety provoking for me!” (Attending) |

| Takes away time with patients at the beside | “I don’t believe open notes is beneficial for patient care. Spend more time perfecting note instead of being with patient.” (Intern) |

| Suggestions for improvement | |

| Prepare parents before receiving notes | “Explain to parents…that there are standard parts and terminology that may be confusing and possibly worrisome to them.” (Attending) |

| Share patient-specific content right away | “Having a patient-specific area to give plan for the day that we can immediately push to patients” that is “ideally without medical jargon.” (Intern) |

| Incorporate asking about notes into rounds | “Probably need to incorporate into daily rounds (ie, asking parents if they have questions about the note).” (Attending) |

Discussion

This pilot study is the first to evaluate sharing notes with parents at the bedside. Despite differences in education, income, health literacy, and reason for admission, parents agreed that access to notes helped them remember their child’s care plan, prepare for rounds, and feel more in control. Although physicians (particularly interns) were skeptical or uncertain about the benefits of sharing, most did not report an increase in their workload. These findings have important implications for children’s hospitals as they work to comply with federal regulations requiring note sharing.15

These results echo the benefits of note sharing revealed in studies with adult outpatients14,28,30,31 and inpatients.16–19 Our findings also highlight the discrepancies between parent, attending, and intern perceptions. Open-ended responses from physicians suggest that many parents did not bring up feedback about notes, which may have made it difficult for physicians to recognize the effects of sharing. Physicians, particularly trainees, may also lack insight into the subjective experiences of patients14,32 and may benefit from feedback from parents on why notes are useful. Finally, some physicians felt the need to change their documentation for parent viewing, which may have impaired team communication and contributed to physician dissatisfaction. Future studies using experimental designs are needed to assess whether perceptions reflect true changes in outcomes.

Most physicians perceived little negative impact of sharing notes on their work. Although increased workload and impaired documentation quality weigh heavily on physicians’ minds,14,16–18,28,33 these challenges have rarely materialized with ambulatory note sharing.20,28 Conversely, many physicians who shared notes with adult outpatients perceived a decrease in their workload because patients used notes to answer their own questions out of respect for their physicians’ time.16–18,28 Future longitudinal studies assessing physician time and effort are needed to adequately determine if, and the degree to which, sharing affects inpatient physician workload.

This single-center, pilot study has limitations. It was conducted with a purposeful sample of available, English-speaking parents on a hospitalist service. Some parents had limited notes exposure; parents were surveyed at the end of the encounter when diagnostic uncertainty is typically resolved; and only discharging physicians were surveyed. Although we had high enrollment and response rates from participants of different backgrounds, findings may not be generalizable and may be subject to selection bias. We did not use validated measures to assess child medical complexity. We also did not assess the release of notes written by or the perceptions of other staff (eg, nurses and subspecialists), nor did we include adolescents, non–English-speaking parents, and parents of children admitted to other services. These are all important areas for future investigation.

Sharing physicians’ notes with parents may be a promising intervention to improve information transparency and engage parents as partners during their child’s hospitalization. Larger multicenter studies are needed to determine if results are replicable at other hospitals and in other populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parent and physician participants for their participation and valuable feedback.

Footnotes

Mr Zellmer performed data collection and analysis, assisted with data interpretation, and drafted and revised the manuscript; Ms Nacht assisted with the literature review, data interpretation, and critical manuscript revisions; Drs Coller, Hoonakker, Smith, Sklansky, and Dean and Ms Smith assisted with study design, data interpretation, and critical manuscript revisions; Ms Sprackling assisted with data collection and interpretation and critical manuscript revisions; Mr Ehlenfeldt assisted with study design, data interpretation, inpatient portal programming, and critical manuscript revisions; Dr Kelly conceived and designed the study, as well as supervised data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant K08HS027214, the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards at the University of Wisconsin-Madison grant 1UL1TR002373, the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health Wisconsin Partnership Program grant 3086, and the Herman and Gwendolyn Shapiro Foundation. Funders had no involvement in data collection, analysis, or interpretation or in the decision regarding manuscript submission. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Sarabu C, Pageler N, Bourgeois F. OpenNotes: toward a participatory pediatric health system. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20180601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeng DD, Graf TR, Davis DE, Tomcavage J, Bloom FJ, Jr. Can a patient-centered medical home lead to better patient outcomes? The quality implications of Geisinger’s ProvenHealth Navigator. Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(3):210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibbard JH. Patient activation and the use of information to support informed health decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dendere R, Slade C, Burton-Jones A, Sullivan C, Staib A, Janda M. Patient portals facilitating engagement with inpatient electronic medical records: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e12779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly MM, Coller RJ, Hoonakker PL. Inpatient portals for hospitalized patients and caregivers: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Coller RJ. Inpatients sign on: an opportunity to engage hospitalized patients and caregivers using inpatient portals. Med Care. 2019;57(2):98–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly MM, Thurber AS, Coller RJ, et al. Parent perceptions of real-time access to their hospitalized child’s medical records using an inpatient portal: a qualitative study. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(4):273–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross SE, Lin CT. The effects of promoting patient access to medical records: a review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(2):129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delbanco T, Walker J, Darer JD, et al. Open notes: doctors and patients signing on. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(2):121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker J, Leveille S, Bell S, et al. OpenNotes after 7 Years: patient experiences with ongoing access to their clinicians’ outpatient visit notes. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):e13876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HealthIT. Information blocking. 2020. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/topic/information-blocking. Accessed June 20, 2020

- 16.Prey JE, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Providing hospital patients with access to their medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:1884–1893 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman LV, Creber RM, Restaino S, Vawdrey DK. Sharing clinical notes with hospitalized patients via an acute care portal. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2017:800–809 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinert C. Giving doctors’ daily progress notes to hospitalized patients and families to improve patient experience. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(1):58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breuch L-AK, Bakke A, Thomas-Pollei K, Mackey E, Weinert C. Toward audience involvement: extending audience of written physician notes in a hospital setting. Writ Commun. 2016;33(4):418–451 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bialostozky M, Huang JS, Kuelbs CL. Are you in or are you out? Provider note sharing in pediatrics. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(1):166–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourgeois FC, DesRoches CM, Bell SK. Ethical challenges raised by OpenNotes for pediatric and adolescent patients. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly MM, Dean SM, Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Hoonakker PL. Healthcare team perceptions of a portal for parents of hospitalized children before and after implementation. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):265–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PL, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan N, Bhaumik DK, Palinkas LA, Hoagwood K. Optimal design and purposeful sampling: complementary methodologies for implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):524–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haun J, Noland-Dodd V, Varnes J, Graham-Pole J, Rienzo B, Donaldson P. Testing the BRIEF health literacy screening tool. Fed Pract. 2009;26(12):24–31 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13(3):313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerard M, Chimowitz H, Fossa A, Bourgeois F, Fernandez L, Bell SK. The importance of visit notes on patient portals for engaging less educated or nonwhite patients: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nazi KM, Turvey CL, Klein DM, Hogan TP, Woods SSVA. VA OpenNotes: exploring the experiences of early patient adopters with access to clinical notes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):380–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobscha SK, Denneson LM, Jacobson LE, Williams HB, Cromer R, Woods S. VA mental health clinician experiences and attitudes toward OpenNotes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;38:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes: hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):414–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]