Abstract

Background: Periodic circadian protein homolog 2 (PER2) has a role in the intracellular signaling pathways of long-term potentiation and has implications for synaptic plasticity. We aimed to assess the association of PER2 C111G polymorphism with cognitive functions in subjective cognitive decline (SCD). Methods: Forty-five SCD patients were included in this study. All participants underwent extensive neuropsychological investigation, analysis of apolipoprotein E (APOE) and PER2 genotypes, and neuropsychological follow-up every 12 or 24 months for a mean time of 9.87 ± 4.38 years. Results: Nine out of 45 patients (20%) were heterozygous carriers of the PER2 C111G polymorphism (G carriers), while 36 patients (80%) were not carriers of the G allele (G non-carriers). At baseline, G carriers had a higher language composite score compared to G non-carriers. During follow-up, 15 (34.88%) patients progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI). In this group, we found a significant interaction between PER2 G allele and follow-up time, as carriers of G allele showed greater worsening of executive function, visual-spatial ability, and language composite scores compared to G non-carriers. Conclusions: PER2 C111G polymorphism is associated with better language performance in SCD patients. Nevertheless, as patients progress to MCI, G allele carriers showed a greater worsening in cognitive performance compared to G non-carriers. The effect of PER2 C111G polymorphism depends on the global cognitive status of patients.

Keywords: subjective cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease, language, visual–spatial ability, executive function, cognitive reserve, PER2 gene, neuropsychology

1. Introduction

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) is defined as a self-experienced decline in cognitive capacity during which individuals have normal performance on standardized cognitive tests [1]. Recent studies on elderly individuals complaining of cognitive impairment have showed a higher association with neuroradiological features similar to those seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, such as volume loss in hippocampal/parahippocampal areas [2] and evidence of amyloid deposition using amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [3] compared to individuals without SCD. Longitudinal studies have showed that cognitive complaints are linked with subsequent change in hippocampal volume [4], and two meta-analysis suggested that individuals experiencing subjective memory impairment are twice as likely to develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia as individuals without [5,6]. Hence, despite SCD being defined on the basis of non-pathological scores at standard neuropsychological assessment, this evidence suggests that SCD should be included into the AD spectrum as an intermediate status between normal cognition and MCI. As a consequence, SCD is getting growing attention as a target population for the identification of Alzheimer’s pathology carriers in a very early stage of the disease. However, the onset of SCD and the risk of progression to MCI and AD is influenced by demographic, cognitive, and genetic factors [7,8,9,10].

Periodic circadian protein homolog 2 (PER2), a clock-controlled gene, has a specific role in the intracellular signaling pathways of long-term potentiation (LTP) and has implications for synaptic plasticity and learned behaviors [11]. Therefore, PER2 is potentially involved in neuropsychological performance and in cognitive changes in the elderly. In a previous study, we focused on the role of PER2 on cognitive functions in SCD and MCI patients [10]. We found that a polymorphism of PER2 (C111G, rs2304672) negatively influenced cognitive performance in patients with MCI. In the SCD group, homozygous carriers of the wild-type allele of PER2 had higher scores on cognitive reserve proxies compared to carriers of the polymorphism. Nevertheless, we detected no association of PER2 C111G with neuropsychological test scores in SCD patients. In order to explain the lack of association, we hypothesized that, at this stage, the detrimental effect of PER2 C111G polymorphism on cognitive functions might not be effective enough to be detected.

In the present work, we aimed to expand our previous results by testing the effect of PER2 C111G polymorphism on cognitive function, with respect to composite psychometric measures instead of single neuropsychological scores, and to evaluate the effect of this polymorphism on changes on cognitive performance during the follow-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Clinical Assessment

As part of an ongoing clinical-neuropsychological-genetic survey on SCD, we included 49 consecutive spontaneous patients who self-referred to the Centre for Alzheimer’s Disease and Adult Cognitive Disorders of Careggi Hospital in Florence between October 1998 and May 2014. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) complaining of cognitive decline with a duration of ≥6 months; (2) normal functioning on the Activities of Daily Living and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales [12]; (3) diagnosis of SCD according to SCD-I criteria [1]; and (4) unsatisfied criteria for MCI or dementia at baseline [13,14]. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of head injury, current neurological and/or systemic disease, symptoms of psychosis, major depression, and/or alcoholism or other substance abuse; (2) a follow-up time shorter than two years; (3) a diagnosis of psychiatric or neurological disease that may cause cognitive impairment; and (4) the complete loss of patient data during follow-up.

All participants underwent the following: (1) collection of a comprehensive family and clinical history, general and neurological examination, extensive neuropsychological investigation, and estimation of premorbid intelligence and assessment of depression; (2) peripheral blood collection in order to analyze apolipoprotein E (APOE) and PER2 genotypes; and (3) clinical and neuropsychological follow-up every 12 or 24 months. A positive family history was defined as one or more first-degree relatives with documented cognitive decline.

From the initial sample (49 patients), we excluded two patients who were diagnosed with psychiatric disturbs, one patient with fronto-temporal dementia [15], and one patient with vascular dementia [16]. Ultimately, we included 45 subjects in the analysis.

On the basis of progression from SCD to MCI, patients were classified as “progressed SCD” (pSCD) or “not progressed SCD” (npSCD).

The study was approved by the local institutional review board. All participants gave their written informed consent. All procedures involving experiments on human subjects were done in compliance with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation of the institution according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and with applicable domestic laws.

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessment

All subjects were evaluated at baseline and every 12 or 24 months by a comprehensive neuropsychological battery as described in more detail elsewhere [17]. Cognitive complaints were explored at baseline using a survey based on the Memory Assessment Clinics-Questionnaire (MAC-Q) [18]. Composite scores for cognitive domains were obtained by arithmetic mean of single test z-scores (calculated according to normative data of the Italian population). In more detail, we considered the following composite scores of cognitive domains: long-term verbal memory, a combination of Five Words Recall and Paired Words Recall after 10 min and after 24 h, Babcock Short Story Recall; executive function: Trail Making test (part B-A); language, a combination of the Token Test and Phonemic Fluency test; visuospatial abilities, a combination of the Trail Making test (part A) and copy of Rey–Osterrieth complex figure test; visuospatial long-term memory (recall of Rey–Osterrieth complex figure test); working memory, and a combination of the digit span and Corsi Block-Tapping Test.

2.3. APOE ε4 and PER2 C111G Genotyping

A standard automated method (QIAcube, QIAGEN) was used to isolate genomic DNA from peripheral blood samples. APOE genotypes were investigated by HRMA (high-resolution melting analysis). Two sets of PCR primers were designed to amplify the regions encompassing rs7412 (NC_000019.9:g.45412079C>T) and rs429358 (NC_000019.9:g.45411941T>C). The APOE genotype was coded as APOE ε4− (no APOE ε4 alleles) and APOE ε4+ (presence of one or two APOE ε4 alleles).

The analyses of the PER2 C111G polymorphism were performed using HRMA, with the following primers: forward 5′-ACAGAAAGAGTCAAATGGGTGC-3′, reverse 5′-TGTCCACATCTTCCTGCAGT-3′ with an annealing temperature of 60 °C. The samples with known PER2 genotypes, which were validated by DNA sequencing, were used as standard references. Patients who were carriers of the polymorphism were classified as “G carriers”, while patients who were not carriers of the polymorphism were classified as “G non-carriers”.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Scores at cognitive tests were reported as z-scores calculated by mean and standard deviation (SD) with respect to the Italian general population reported in literature for each neuropsychological test [17,19,20,21,22,23]. We tested for the normality distribution of the data using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Patient groups were characterized by using means and SD, median and interquartile range (IQR), and frequencies or percentages and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for continuous distributed variables, continuous non-normally distributed variables, and categorical variables, respectively. We used t-tests or non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests for between groups’ comparisons, Pearson’s correlation coefficient or non-parametric Spearman’s ρ (rho) to evaluate correlations between groups’ numeric measures, and chi-square tests to compare categorical data. We used binomial logistic regression for multivariate analysis. To estimate the effect of PER2 polymorphism on neuropsychological test scores over time, we used generalized estimating equations. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software v.25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample and Comparison of Demographic Features between G Carriers and G Non-Carriers

Of the whole sample, 33 patients were women and 12 were men. The mean age at baseline evaluation was 61.26 ± 8.65 years. Thirteen patients (37.14% [95% CI 22.70–51.78]) were carriers of the APOE ε4 allele (APOE ε4+). Nine out of 45 patients (20.00% [95% CI 8.04–31.96]) were carriers of the CG genotype (G carriers), while 36 patients (80.00% [95% CI 68.04–91.96%]) were carriers of the CC genotype (G non-carriers). None of the patients was carrier of the GG genotype. The genotypic distribution of PER2 gene was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 = 0.56, p > 0.05). We found no difference between G carriers and G non-carriers with respect to age at baseline, disease duration (time from onset of symptoms and baseline evaluation), sex, score of scale for depression, APOE ε4 allele frequency, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). G carriers had less years of education (8.00 [IQR 7.00] vs. 12.00 [IQR 9.00], U = 75.50, z = −12.47, p = 0.012) as compared to G non-carriers (Table 1). No differences in single neuropsychological z-scores were found between G carriers and G non-carriers (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic, cognitive, and genetic features between G carriers and G non-carriers.

| Variable | G Non-Carriers | G Carriers | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 36 | 9 | |

| Age at baseline, median (IQR) | 60.80 (17.24) | 62.44 (9.81) | 0.758 |

| Disease duration, median (IQR) | 3.82 (2.92) | 3.33 (4.24) | 0.092 |

| Sex (no. women/no. men) | 25/11 | 8/1 | 0.241 |

| Education, median (IQR) | 12.00 (9.00) | 8.00 (7.00) | 0.016 |

| APOE ε4+, % (95% CI) | 30.55 (16.78–44.32) | 22.22 (9.79–34.65) | 0.625 |

| MMSE, median (IQR) | 27.00 (3.70) | 26.61 (4.70) | 0.251 |

| HDRS, median (IQR) | 4.00 (6.00) | 5.50 (4.00) | 0.303 |

| MAC-Q, median (IQR) | 25.00 (3.00) | 25.50 (4.00) | 0.326 |

| Long-term verbal memory, median (IQR) | 0.42 (0.54) | 0.25 (0.62) | 0.244 |

| Working memory, median (IQR) | −1.25 (1.61) | −1.03 (1.61) | 0.770 |

| Visual–spatial memory, median (IQR) | 0.36 (0.83) | 0.00 (0.18) | 0.163 |

| Visual–spatial ability, median (IQR) | 0.40 (±0.61) | 0.49 (±0.47) | 0.694 |

| Executive function, median (IQR) | 0.65 (±0.40) | 0.97 (±0.72) | 0.305 |

| Language, median (IQR) | 0.25 (0.94) | 0.62 (0.52) | 0.018 |

Values quoted in the table are mean and standard deviation (SD), medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), frequencies or percentages, and 95% CI. Age at baseline, disease duration, and education are expressed in years. Cognitive composite scores are expressed as z-scores. p indicates level of significance for comparison between G carriers and G non-carriers (statistical significance at the p < 0.05). Abbreviations: MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; HDRS: Hamilton Depression rating scale; MAC-Q: Memory Assessment Clinics-Questionnaire.

3.2. Comparison of Neuropsychological Composite Scores between G Carriers and G Non-Carriers at Baseline

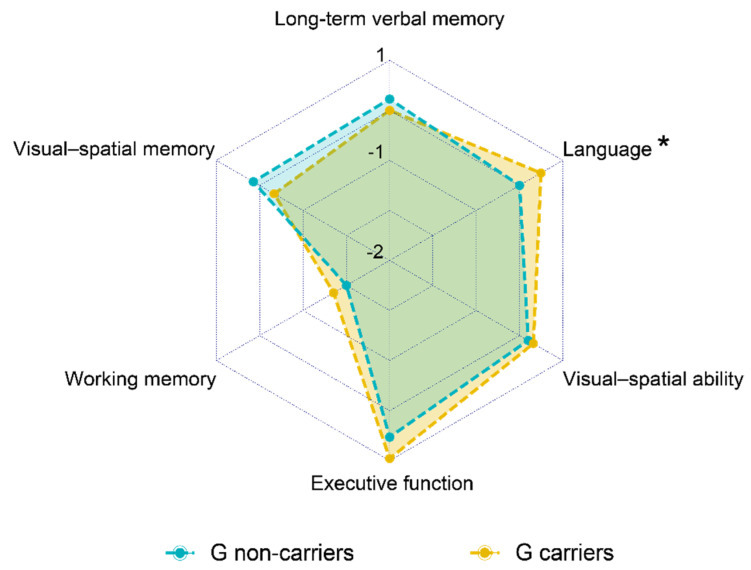

G carriers had higher language composite score compared to G non-carriers (0.25 [IQR 0.94] vs. 0.62 [IQR 0.52], U = 237.5, z = 2.33, p = 0.018). No difference with respect to the other cognitive domains were found between G carriers and G non-carriers (Table 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of composite score for each cognitive domain between G carriers and G non-carriers. Values quoted in the axis are median values. Language composite score (*) was higher in G carriers as compared to G non-carriers (0.25 [IQR 0.94] vs. 0.62 [IQR 0.52], p = 0.018).

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

In order to ascertain that the difference in language composite score between G carriers and G non-carriers was independent from possible confounding variables, we carried out a binomial logistic regression. We considered language, years of education, age, sex, disease duration, and APOE genotype as covariates and PER2 C111G genotype as a dependent variable. The regression model was statistically significant (χ2 = 18.0, p = 0.006). The model explained 52.7% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in conversion and correctly classified 88.6% of cases. Of the covariates considered for the analysis, only lower education (Wald = 4.05, p = 0.044, OR = 0.71 [95% CI 0.50–0.99]) and higher language score (Wald = 4.92, p = 0.027, OR = 25.79 [95% CI 1.44–462.50]) were significantly associated with a higher proportion of G allele (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression model for multivariate analysis.

| B | Wald | p | OR | 95% C.I. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| 3.32 | 4.92 | 0.027 | 25.79 | 1.44 | 462.50 | |

| Education (years) | −0.345 | 4.05 | 0.044 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.99 |

| Age (years) | −0.05 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.10 |

| Disease duration (years) | −0.30 | 2.16 | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 1.11 |

| Female sex | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 1.41 | 0.10 | 20.22 |

| APOE ε4+ | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 1.53 | 0.15 | 16.06 |

| Constant | 4.82 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 124.46 | ||

Regression coefficients (B), Wald coefficients, p-values (p), odds ratios (ORs), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are shown. All the covariates included in the analysis are reported. PER2 C111G genotype (G or CC) was considered a dependent variable. The regression model was statistically significant (χ2 = 18.0, p = 0.006). Language and education were statistically significant (significant differences at p < 0.05).

3.4. Longitudinal Association of PER2 Genotype with Cognitive Performance

Patients were followed-up for a mean time of 9.87 ± 4.38 years. During this period, 15 (34.88% [95% CI 20.63–49.13]) patients progressed to MCI (pSCD). Thirty patients (65.12% [95% CI 50.87–79.37]) did not progress. Two out of 15 pSCD patients (13.33%) and five out of 30 npSCD patients (16.67%) were G carriers. There were no differences between pSCD and npSCD groups with respect to age at baseline, disease duration, follow-up time, years of education, MMSE, Hamilton Depression rating scale (HDRS), MAC-Q, and APOE ε4 and PER2 G allele proportion. No differences in cognitive domain composite scores were found between G carriers and G non-carriers at the last follow-up evaluation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the demographic, cognitive, and genetic features between G carriers and G non-carriers at the last follow-up evaluation.

| Variable | G Non-Carriers | G Carriers | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 36 | 9 | |

| Long-term verbal memory, median (IQR) | 0.07 (0.94) | 0.13 (0.87) | 0.547 |

| Working memory, median (IQR) | −1.25 (1.03) | −1.25 (0.79) | 0.833 |

| Visual-spatial memory, median (IQR) | 0.82 (1.19) | 0.22 (2.08) | 0.276 |

| Visual-spatial ability, median (IQR) | 0.50 (0.71) | 0.76 (0.99) | 0.323 |

| Executive function, median (IQR) | 0.51 (0.71) | 0.37 (1.91) | 0.838 |

| Language, median (IQR) | 0.20 (0.86) | 0.18 (0.46) | 0.850 |

Values quoted in the table are mean and standard deviation (SD), medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), frequencies or percentages, and 95% CI. Age at baseline, disease duration, and education are expressed in years. Cognitive composite scores are expressed as z-scores. p indicates level of significance for comparison between G carriers and G non-carriers (statistical significance at the p < 0.05).

In order to explore the effect of PER2 polymorphism on changes on cognitive performance during follow-up, we ran generalized estimating equations. We considered baseline evaluation and last follow-up neuropsychological evaluation as within-subjects variables, composite z-scores of each cognitive domain as dependent variables, and PER2 genotype (G carrier or G non-carriers) and follow-up time (years between first and last neuropsychological evaluation) as predictors. The model included follow-up time and interaction of follow-up time with PER2 genotype.

For the whole sample, we did not find any effect of PER2 polymorphism on changes in cognitive performance during the follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Generalized estimating equations as a function of PER2 genotype over follow-up time.

| Follow-Up Time | Follow-Up Time × G Allele | |

|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Long-term verbal memory | 0.942 (0.889:0.999) | 1.016 (0.918:1.125) |

| Working memory | 1.013 (0.973:1.054) | 0.971 (0.922:1.023) |

| Visual–spatial memory | 1.034 (0.986:1.085) | 0.987 (0.856:1.138) |

| Visual–spatial ability | 1.030 (0.993:1.068) | 0.973 (0.874:1.083) |

| Executive function | 0.974 (0.944:1.006) | 0.335 (0.595:1.193) |

| Language | 0.995 (0.975:1.015) | 0.971 (0.923:1.021) |

β coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for model including time and time × G allele are reported. There was no significant effect of PER2 polymorphism on changes in cognitive performance during the follow-up.

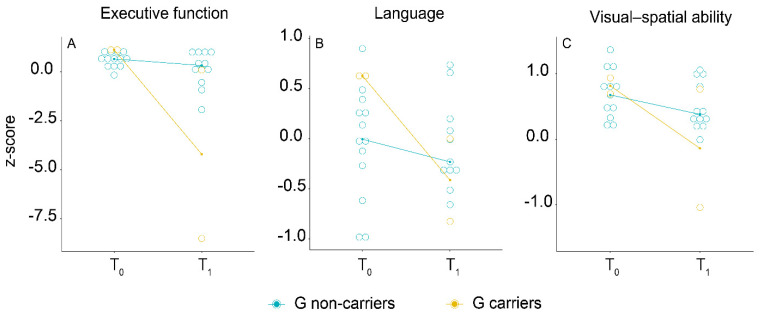

We ran the same analysis on pSCD and npSCD separately. No significant differences with respect to demographic features, follow-up time, HDRS, MAC-Q, APOE ε4, and MMSE were found between G carriers and G non-carriers at baseline. During follow-up, pSCD patients who were carriers of G allele showed greater worsening of executive function (0.921 [95% CI 0.897:0.946], p < 0.001, Figure 2A), language (β = 0.560 [95% CI 0.475:0.660], p < 0.001, Figure 2B), and visual–spatial ability (β = 0.885 [95% CI 0.827:0.946], p < 0.001, Figure 2C) composite scores compared to G non-carriers (Table 5). We did not find any effect of PER2 polymorphism on changes in cognitive performance during the follow-up in the npSCD subsample.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal association of PER2 genotype with composite scores for executive function (A), language (B), and visual–spatial ability (C) in the “progressed SCD” (pSCD) group. On the x-axis, T0 indicates the baseline evaluation and T1 indicates the last neuropsychological evaluation. On the y-axis, median of composite scores (z-score) for each cognitive domain are reported.

Table 5.

Generalized estimating equations for neuropsychological scores as a function of PER2 genotype over follow-up time.

| Cognitive Domains | Time | Time × G Allele |

|---|---|---|

| β (95% C.I) | β (95% C.I) | |

| Long-term verbal memory | 0.823 (0.785:0.862) *** | 1.049 (0.995:1.106) |

| Working memory | 1.017 (0.972:1.063) | 0.449 (0.108:1.866) |

| Visual–spatial memory | 0.987 (0.938:1.038) | 0.980 (0.788:1.006) |

| Visual–spatial ability | 0.977 (0.954:1.047) | 0.885 (0.827:0.946) *** |

| Executive function | 0.979 (0.954:1.005) | 0.921 (0.897:0.946) *** |

| Language | 0.941 (0.885:1.001) | 0.560 (0.475:0.660) *** |

β coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for model including time and time × G allele are reported. *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

The potential role of PER2 on cognitive functions has been suggested by a number of studies on in vitro and mouse models [24,25]. However, the role and the mechanism of PER2 in neurobiological activities is still poorly understood. PER2 is one of the core genes of the circadian clock and has a role in generating circadian rhythms [26,27]. In the brain, it is mainly expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, midbrain, and forebrain [28,29]. Furthermore, it has been linked with the modulation of the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine [29,30], glutamate [31,32], GABA [33], and serotonin [34,35]. More recently, a number of studies searched for a role of PER2 in neurodegenerative disease, with conflicting results observed: PER2 expression was attenuated in AD mouse models, but studies on humans failed to find an association between PER2 and AD [36,37,38]. Our results provide clues for a role of PER2 in cognition in humans as well. Nevertheless, its effect may be much more complex than being just a risk or protective factor, with a relationship described by a non-linear function.

As the first result, we showed that PER2 C111G polymorphism is associated with cognitive functions in SCD patients. We recently showed that PER2 C111G polymorphism has a detrimental role on single neuropsychological test scores assessing for language, memory, executive function, and visual–spatial ability in patients with MCI [10]. In the present analysis, we found an opposite effect of this polymorphism in patients with SCD, as carriers of the polymorphism performed better than non-carriers on a language composite score. This evidence may appear in contrast with our previous findings. Nevertheless, as a preliminary result on a subgroup of patients, we underlined that among patients who progressed to MCI, G allele carriers showed a greater worsening in language, executive function, and visual-spatial ability.

This result may suggest that the effect of the PER2 variant on cognitive functions depends on the global cognitive status of subjects. In other words, we might hypothesize that cognitively healthy subjects who are carriers of the PER2 C111G polymorphism have an advantage with regard to linguistic performance, but this effect might disappear in the progression to MCI. A similar phenomena has been described for a polymorphism of BDNF gene [39], and resembles the dimorphic effect of cognitive reserve on progression from SCD to MCI and from MCI to AD [7,40]. Our results precisely showed that a relationship exists between PER2 and cognitive reserve. Indeed, studies on mouse models found that PER2 is involved in the mechanism of long-term potentiation, synaptic plasticity, and learned behaviors [11]. Therefore, our results may suggest an implication of the PER2 gene on a mechanism underling cognitive reserve in humans. Further studies on this topic, especially those including a larger number of patients, will provide crucial findings to expand our knowledge of the neurobiological mechanism of neuropsychological processes and the development of cognitive reserve.

This study has remarkable strengths. First of all, we would like to emphasize that this is the first study assessing the effect of PER2 C111G polymorphism on cognition in SCD patients. Secondly, in addition to neuropsychological scores, our analysis included other measures estimating features involved in cognitive performance (cognitive reserve, mood state, and cognitive complaint). This provides useful data to exclude possible confounding factors and to support our findings. Finally, our longitudinal analyses are based on data from a very long follow-up time.

The small size of our cohort of patients is the first limitation of our study. In particular, only nine patients were G carriers in the whole sample, and only two patients were G carriers in the pSCD group. This limits our conclusions and means that, in order to ground our findings, we shall expand our sample. Also, we must point out that, despite a long mean follow-up time, we encountered a high variability in follow-up times, as shown by the SD value of this variable. Another limitation is the lack of AD biomarkers data. Finally, as it is a single-center study, there may be biases with regard to assessment and diagnosis procedures.

5. Conclusions

PER2 C111G polymorphism differently influences cognitive functions according to the global cognitive status of the subject. In particular, the PER2 G allele seems to provide an advantage in relation to language in cognitively healthy subjects. Nevertheless, in patients who progress to objective cognitive impairment, this advantage seems to disappear, and the G allele is associated with a greater decline in language, executive function, and visual–spatial ability. Our findings pave the way to future research on the implication of the PER2 gene on the neurobiological mechanism(s) underling cognitive reserve, as well as the neuropsychological functions in healthy and in cognitively impaired patients and in neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics11040718/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.M., V.B., S.P., and L.B.; methodology: S.M., V.B., S.B., and A.I.; formal analysis: S.M.; investigation: S.M., V.B., G.G., and G.T.; resources, S.M., V.B., S.B., and C.F.; data curation: S.M., G.G., J.B., and G.T.; writing—original draft preparation: S.M. and V.B.; writing—review and editing: S.M., V.B., and B.N.; supervision: V.B., B.N., and S.S.; project administration: V.B.; funding acquisition: V.B., B.N., and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was funded by Tuscany Region (GRANT n° 20RSVB—PREVIEW: PRedicting the EVolution of SubjectIvE Cognitive Decline to Alzheimer’s Disease With machine learning) and by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (ECRF1—GRANT 2015.0713).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Azienda Ospedaliaro-Universitaria Careggi”, Florence, Italy (reference 15691oss).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data that support the findings of this study will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jessen F., Amariglio R.E., van Boxtel M., Breteler M., Ceccaldi M., Chételat G., Dubois B., Dufouil C., Ellis K.A., van der Flier W.M., et al. A Conceptual Framework for Research on Subjective Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perrotin A., Mormino E.C., Madison C.M., Hayenga A.O., Jagust W.J. Subjective Cognition and Amyloid Deposition Imaging: A Pittsburgh Compound B Positron Emission Tomography Study in Normal Elderly Individuals. Arch. Neurol. 2012;69:223–229. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amariglio R.E., Becker J.A., Carmasin J., Wadsworth L.P., Lorius N., Sullivan C., Maye J.E., Gidicsin C., Pepin L.C., Sperling R.A., et al. Subjective Cognitive Complaints and Amyloid Burden in Cognitively Normal Older Individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart R., Godin O., Crivello F., Maillard P., Mazoyer B., Tzourio C., Dufouil C. Longitudinal Neuroimaging Correlates of Subjective Memory Impairment: 4-Year Prospective Community Study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2011;198:199–205. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell A.J., Beaumont H., Ferguson D., Yadegarfar M., Stubbs B. Risk of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older People with Subjective Memory Complaints: Meta-Analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014;130:439–451. doi: 10.1111/acps.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parfenov V.A., Zakharov V.V., Kabaeva A.R., Vakhnina N.V. Subjective Cognitive Decline as a Predictor of Future Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2020;14:248–257. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzeo S., Padiglioni S., Bagnoli S., Bracco L., Nacmias B., Sorbi S., Bessi V. The Dual Role of Cognitive Reserve in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 7-Year Follow-up Study. J. Neurol. 2019;266:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzeo S., Bessi V., Padiglioni S., Bagnoli S., Bracco L., Sorbi S., Nacmias B. KIBRA T Allele Influences Memory Performance and Progression of Cognitive Decline: A 7-Year Follow-up Study in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neurol. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bessi V., Mazzeo S., Padiglioni S., Piccini C., Nacmias B., Sorbi S., Bracco L. From Subjective Cognitive Decline to Alzheimer’s Disease: The Predictive Role of Neuropsychological Assessment, Personality Traits, and Cognitive Reserve. A 7-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;63:1523–1535. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessi V., Giacomucci G., Mazzeo S., Bagnoli S., Padiglioni S., Balestrini J., Tomaiuolo G., Piaceri I., Carraro M., Bracco L., et al. PER2 C111G Polymorphism, Cognitive Reserve and Cognition in Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment. A 10-Year Follow-up Study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ene.14518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L.M.-C., Dragich J.M., Kudo T., Odom I.H., Welsh D.K., O’Dell T.J., Colwell C.S. Expression of the Circadian Clock Gene Period2 in the Hippocampus: Possible Implications for Synaptic Plasticity and Learned Behaviour. ASN Neuro. 2009;1 doi: 10.1042/AN20090020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawton M.P., Brody E.M. Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C., Gamst A., Holtzman D.M., Jagust W.J., Petersen R.C., et al. The Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Kawas C.H., Klunk W.E., Koroshetz W.J., Manly J.J., Mayeux R., et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neary D., Snowden J.S., Gustafson L., Passant U., Stuss D., Black S., Freedman M., Kertesz A., Robert P.H., Albert M., et al. Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: A Consensus on Clinical Diagnostic Criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Román G.C., Tatemichi T.K., Erkinjuntti T., Cummings J.L., Masdeu J.C., Garcia J.H., Amaducci L., Orgogozo J.M., Brun A., Hofman A. Vascular Dementia: Diagnostic Criteria for Research Studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bracco L., Amaducci L., Pedone D., Bino G., Lazzaro M.P., Carella F., D’Antona R., Gallato R., Denes G. Italian Multicentre Study on Dementia (SMID): A Neuropsychological Test Battery for Assessing Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1990;24:213–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90011-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crook T.H., Feher E.P., Larrabee G.J. Assessment of Memory Complaint in Age-Associated Memory Impairment: The MAC-Q. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1992;4:165–176. doi: 10.1017/S1041610292000991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caffarra P., Vezzadini G., Dieci F., Zonato F., Venneri A. Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure: Normative Values in an Italian Population Sample. Neurol. Sci. 2002;22:443–447. doi: 10.1007/s100720200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baddeley A., Della Sala S., Papagno C., Spinnler H. Dual-Task Performance in Dysexecutive and Nondysexecutive Patients with a Frontal Lesion. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:187–194. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.11.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spinnler H., Tognoni G. Standardizzazione e Taratura Italiana Di Test Neuropsicologici: Gruppo Italiano per Lo Studio Neuropsicologico Dell’invecchiamento. Masson Italia Periodici; Milano, Italy: 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giovagnoli A.R., Del Pesce M., Mascheroni S., Simoncelli M., Laiacona M., Capitani E. Trail Making Test: Normative Values from 287 Normal Adult Controls. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996;17:305–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01997792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brazzelli M., Della Sala S., Laiacona M. Calibration of the Italian Version of the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test: A Test for the Ecological Evaluation of Memory. Boll. Psicol. Appl. 1993;206:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozon B., Kelly A., Josselyn S.A., Silva A.J., Davis S., Laroche S. MAPK, CREB and Zif268 Are All Required for the Consolidation of Recognition Memory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2003;358:805–814. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lonze B.E., Ginty D.D. Function and Regulation of CREB Family Transcription Factors in the Nervous System. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arjona A., Sarkar D.K. The Circadian Gene MPer2 Regulates the Daily Rhythm of IFN-Gamma. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:645–649. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sujino M., Nagano M., Fujioka A., Shigeyoshi Y., Inouye S.-I.T. Temporal Profile of Circadian Clock Gene Expression in a Transplanted Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and Peripheral Tissues. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:2731–2738. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albrecht U., Sun Z.S., Eichele G., Lee C.C. A Differential Response of Two Putative Mammalian Circadian Regulators, Mper1 and Mper2, to Light. Cell. 1997;91:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80495-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hood S., Cassidy P., Cossette M.-P., Weigl Y., Verwey M., Robinson B., Stewart J., Amir S. Endogenous Dopamine Regulates the Rhythm of Expression of the Clock Protein PER2 in the Rat Dorsal Striatum via Daily Activation of D2 Dopamine Receptors. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14046–14058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2128-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gravotta L., Gavrila A.M., Hood S., Amir S. Global Depletion of Dopamine Using Intracerebroventricular 6-Hydroxydopamine Injection Disrupts Normal Circadian Wheel-Running Patterns and PERIOD2 Expression in the Rat Forebrain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2011;45:162–171. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spanagel R., Pendyala G., Abarca C., Zghoul T., Sanchis-Segura C., Magnone M.C., Lascorz J., Depner M., Holzberg D., Soyka M., et al. The Clock Gene Per2 Influences the Glutamatergic System and Modulates Alcohol Consumption. Nat. Med. 2005;11:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yelamanchili S.V., Pendyala G., Brunk I., Darna M., Albrecht U., Ahnert-Hilger G. Differential Sorting of the Vesicular Glutamate Transporter 1 into a Defined Vesicular Pool Is Regulated by Light Signaling Involving the Clock Gene Period2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15671–15679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straub R.H., Cutolo M. Circadian Rhythms in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Implications for Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Management. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:399–408. doi: 10.1002/art.22368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendoza J., Clesse D., Pévet P., Challet E. Serotonergic Potentiation of Dark Pulse-Induced Phase-Shifting Effects at Midday in Hamsters. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:1404–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caldelas I., Challet E., Saboureau M., Pevet P. Light and Melatonin Inhibit in Vivo Serotonergic Phase Advances without Altering Serotonergic-Induced Decrease of per Expression in the Hamster Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2005;25:53–63. doi: 10.1385/JMN:25:1:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yesavage J.A., Noda A., Hernandez B., Friedman L., Cheng J.J., Tinklenberg J.R., Hallmayer J., O’hara R., David R., Robert P., et al. Circadian Clock Gene Polymorphisms and Sleep-Wake Disturbance in Alzheimer Disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2011;19:635–643. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820d92b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira P.A., Alvim-Soares A., Bicalho M.A.C., de Moraes E.N., Malloy-Diniz L., de Paula J.J., Romano-Silva M.A., Miranda D.M. Lack of Association between Genetic Polymorphism of Circadian Genes (PER2, PER3, CLOCK and OX2R) with Late Onset Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease in a Sample of a Brazilian Population (Circadian Genes, Late-Onset Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:1397–1406. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160603005630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cermakian N., Lamont E.W., Boudreau P., Boivin D.B. Circadian Clock Gene Expression in Brain Regions of Alzheimer ’s Disease Patients and Control Subjects. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2011;26:160–170. doi: 10.1177/0748730410395732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bessi V., Mazzeo S., Bagnoli S., Padiglioni S., Carraro M., Piaceri I., Bracco L., Sorbi S., Nacmias B. The Implication of BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism in Progression from Subjective Cognitive Decline to Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A 9-Year Follow-up Study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;270:471–482. doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-01069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stern Y. Cognitive Reserve in Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data that support the findings of this study will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.