Abstract

Introduction

Targeted, tailored interventions to test high-risk individuals for HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are vital to achieving HIV control and HCV microelimination in Africa. Compared with the general population, people who inject drugs (PWID) are at increased risk of HIV and HCV and are less likely to be tested or successfully treated. Assisted partner services (APS) increases HIV testing among partners of people living with HIV and improves case finding and linkage to care. We describe a study in Kenya examining whether APS can be adapted to find, test and link to HIV care the partners of HIV-positive PWID using a network of community-embedded peer educators (PEs). Our study also identifies HCV-positive partners and uses phylogenetic analysis to determine risk factors for onward transmission of both viruses.

Methods

This prospective cohort study leverages a network of PEs to identify 1000 HIV-positive PWID for enrolment as index participants. Each index completes a questionnaire and provides names and contact information of all sexual and injecting partners during the previous 3 years. PEs then use a stepwise locator protocol to engage partners in the community and bring them to study sites for enrolment, questionnaire completion and rapid HIV and HCV testing. Outcomes include number and type of partners per index who are mentioned, enrolled, tested, diagnosed with HIV and HCV and linked to care.

Ethics and dissemination

Potential index participants are screened for intimate partner violence (IPV) and those at high risk are not eligible to enrol. Those at medium risk are monitored for IPV following enrolment. A community advisory board engages in feedback and discussion between the community and the research team. A safety monitoring board discusses study progress and reviews data, including IPV monitoring data. Dissemination plans include presentations at quarterly Ministry of Health meetings, local and international conferences and publications.

Trial registration number

NCT03447210, Pre-results stage.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, hepatology, international health services, epidemiology, molecular diagnostics, virology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cohort study investigates the use of assisted partner services (APS) to find, test for HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) and link to care the sexual and injecting partners of HIV-positive people who inject drugs in Kenya; however, APS is not offered to HIV-negative, HCV-positive clients to identify those exposed to HCV but not HIV.

Community-embedded peer educators trained to provide harm reduction services conduct partner tracing, but there are limitations including logistical challenges and concerns for client confidentiality and safety of both the client and peer educator.

An iris scanning biometric identification system ensures that each index participant enrolled is a unique individual and confirms that individual partner participants who enrol more than once in relation to different index participants are the same individual.

Phylogenetic analysis of HIV and HCV viral sequences combined with APS will provide additional information about transmission dynamics within the cohort, including risk of onward transmission for different clusters and geographic regions.

Introduction

Diagnosing 90% of those living with HIV has been among the most difficult of the UNAIDS 90–90–90 goals to achieve worldwide,1 2 and strategies to reach individuals at high-risk for HIV who have never been tested is increasingly important.3 In Kenya, despite success in achieving or approaching the second and third UNAIDS goals, only 79.4% of people testing for HIV know their status.4 Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is the most efficient mode of HIV transmission and accounts for 13% of new infections globally.5 6 In Kenya, prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs (PWID) has been estimated at 15%–50%,6–10 significantly higher than the general population prevalence of 4.9%,11 and up to 30% of PWID in Kenya have never tested for HIV.12 13 Multiple studies have demonstrated low knowledge of HIV status and low engagement in care among Kenya’s PWID.13 14 Retention in care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) are also both lower among PWID as compared with others worldwide.1

In addition to HIV, PWID are at high risk for hepatitis C virus (HCV) globally and have the highest HCV prevalence of any group studied in Kenya at 13%–40%.10 15 16 This is especially high when compared with the general population HCV prevalence in Kenya of <1%–4%.17 18 However, multiple barriers exist at individual, provider and system levels resulting in low rates of testing, engagement in care and completion of treatment courses for PWID.19–21 Although less than 20% of PWID with chronic HCV worldwide have undergone antibody screening, the number who have completed PCR confirmatory testing is even lower.22 Despite the introduction of highly effective direct-acting antivirals into Kenya in 2016, only a small fraction of individuals living with HCV have been treated, prompting attention to microelimination strategies.23 24

Assisted partner services (APS) for HIV is an evidence-based partner notification strategy in which providers elicit information about the sexual or injecting partners of an HIV-positive index client, and then contact, HIV test and link to care any partners found to be positive.25 APS has been shown to significantly and safely increase the uptake of HIV testing services (HTS), case finding and linkage to care for partners of HIV-positive people.25–27 APS can also reduce barriers to disclosing HIV status28 and is cost-effective.29 APS has been successfully implemented among HIV-positive patients from the general population in the USA,30 Mozambique,31 Malawi32 33 and Kenya27 and has recently been incorporated into the WHO guidelines for routine care for HIV-positive people worldwide.34 While programmes have introduced the practice of APS in high-risk key populations (KPs) such as female sex workers (FSWs)35 and men who have sex with men (MSM),36 37 this intervention has not been well studied among PWID,38 an extremely high risk group.25 39 Similar to FSW and MSM, PWID engage in behaviour that is criminalised in many parts of the world40 while experiencing high rates of marginalisation and displacement,41 making them difficult to study. These factors and others also contribute to significant barriers in the implementation of health programmes targeting PWID.42–44

Phylogenetic analysis is a method of identifying the role of specific risk groups and risk factors for onward transmission of HIV and HCV using the genetic sequence of each virus.45–47 Viral phylogenetics can provide additional information on patterns of transmission,48–50 epidemic growth,51 52 risk groups53–55 and risk factors associated with onward transmission.47 56–58

Here we describe a prospective cohort study that seeks to determine whether and how APS can be implemented to find, test and link to care the injection and sexual partners of HIV-positive PWID in Kenya. Simultaneously, our study will use phylogenetic analysis to study genetic sequences of HIV and HCV within our cohort to further understand transmission patterns and risk for onward transmission. All index and partner participants are tested for HCV in addition to HIV. While many partner contact methods for conducting APS have been used,25 cellular telephones are the most common first-line communication modality for reaching partners in other populations.26 27 31 59 In Kenya, however, the large majority of PWID do not have regular access to cellular telephones. As such, our APS model relies on the utilisation of community-embedded peer educators (PEs) to locate and communicate with members of this difficult to reach population. We hypothesise that we will be able to employ these customised APS procedures to reach a large number of injection and sexual partners and that we will see differences between sexual and injection partners in uptake of HIV testing, HIV and HCV prevalence and engagement in care. Additionally, we hypothesise that we will identify unique transmission patterns and risks for onward transmission in phylogenetic analysis, which may include behavioural, geographic or other factors.

Methods and analysis

Approach

APS is a practice through which healthcare providers facilitate the notification, testing and linkage to care for partners who may have been exposed to HIV or other sexually transmitted infections by an individual known to be positive without revealing the identity of the person who may have exposed them. While there are many ways to provide partner services, APS in Kenya is often conducted by healthcare providers who elicit information about partners from an ‘index’ patient and then call the partners over the telephone or physically trace them to alert them to their exposure and provide testing. We have designed customised procedures to ensure and improve the safety and efficacy of APS in the unique population of PWID in Kenya. Because PWID and their partners in Kenya rarely own cellular phones, we work with community-embedded PEs to find and engage with partners. Additionally, our protocol involves referrals to different facilities for injection partners and for sexual partners, as a precaution to ensure safety and confidentiality of index participants who may theoretically be at risk of negative outcomes if partners become aware of their HIV-positive status.

Study design

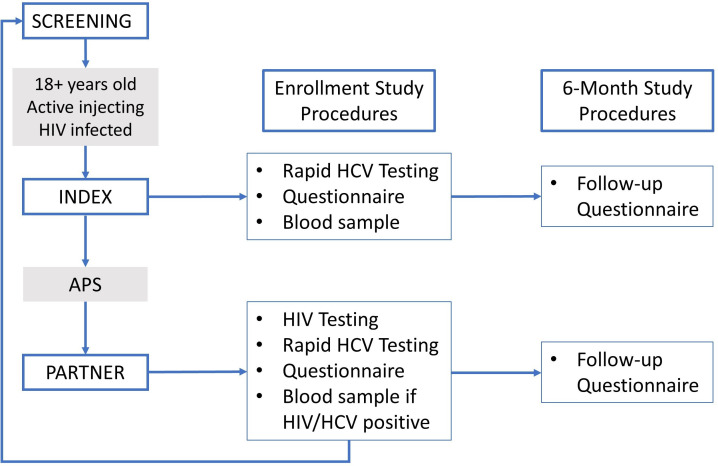

Our study is a prospective cohort study with two groups: index and partner participants (‘indexes’ and ‘partners’). We use tailored APS procedures to identify, find, test and link to care the sexual and injection partners of HIV-positive PWID. All index participants, as well as partner participants who are diagnosed with HIV or HCV, complete a 6-month follow-up visit to assess linkage to and engagement in care.

Study sites/setting

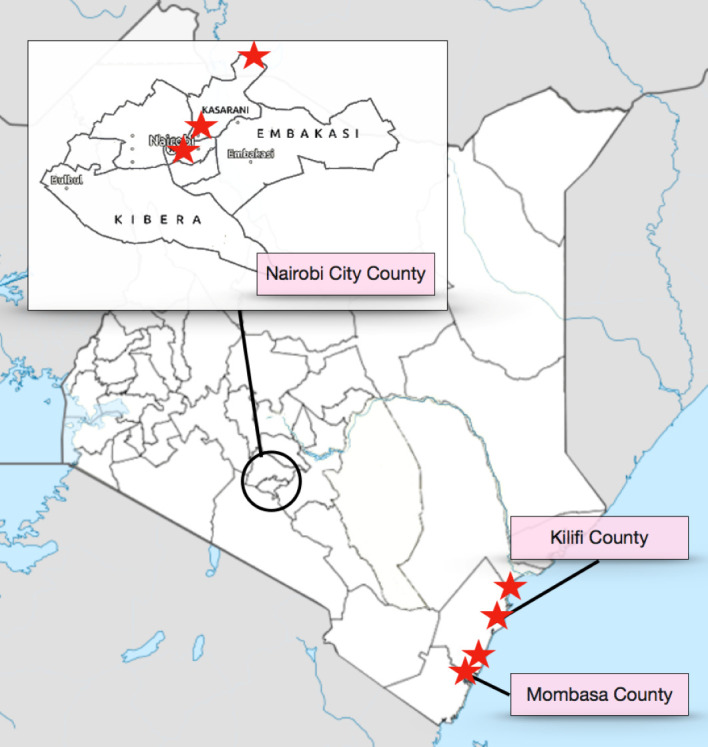

Study procedures take place in eight main sites including public health centres, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) centres and needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) in Nairobi, Kilifi and Mombasa Counties in Kenya (figure 1). Each site is staffed by at least one clinical officer (midlevel clinician) who works with researchers to ensure that only participants with documented HIV infection are enrolled as indexes, verifying HIV status through retesting if documentation is not provided. In Nairobi County, the activities are centred at two NSP sites and one MAT centre in the Mathare North area. The NSP sites, run by Support for Addiction Prevention and Treatment in Africa, offer routine HTSs. Referrals are made to local clinics providing care for those who test positive for HIV or HCV. We also recruit indexes from a government-run methadone clinic in Nairobi in the Ngara area. The Ngara Health Center MAT clinic offers HIV testing, care and treatment in addition to daily methadone administration, psychosocial services and treatment for other health conditions. In Kilifi County, participant recruitment and enrolment takes place at three NSP centres and one government hospital. The Omari Project is located in Malindi town and offers HIV counselling, testing, care and treatment in addition to harm reduction services. Malindi Sub-County Hospital’s MAT centre is a recruitment site in Kilifi County within a midsized government hospital that offers a large range of medical and social services. Malindi Sub-County Hospital also has a large laboratory that houses the study’s samples collected in both Kilifi and Mombasa Counties. The Muslim Education and Welfare Association NSP sites in Kilifi and Mtwapa towns offer HIV counselling and testing, in addition to HIV care and treatment and harm reduction services. In Mombasa County, participants are recruited from the ReachOut Center, an NSP site in Mombasa City that offers a full range of harm reduction services in addition to HIV counselling, testing, care and treatment. All recruitment sites offer routine HCV testing when kits are available through specific donor-driven projects.

Figure 1.

Map of study sites.

Population

This study includes index participants and their sexual and/or drug-injecting partners. All indexes are HIV-positive PWID. Partners are either sexual partners or injecting partners of indexes.

Indexes are largely recruited from organisations and clinics that provide services to PWID populations, although they may also come from outreach efforts or informal referrals from other participants. Partners are identified and recruited through peer-mediated APS and may come from any geographic area or community.

Patient and public involvement

Members of the community of PWID being researched were consulted in the development of research questions and design of the study. The study is supported by a Community Advisory Board (CAB) composed of members of the community, PEs and employees of organisations that provide services to the population. The CAB meets with the study team regularly and helps inform dissemination plans.

Study procedures

PE recruitment and training

PEs are recovering PWID with established relationships in the PWID communities that they serve. The majority are between the ages of 25 and 50 years, are enrolled in Kenya’s methadone programme and report having stopped injecting drugs. These men and women have been identified by the individual organisations at which they work as being key community members and have undergone extensive training for their roles as PEs. Training is an intensive 5-day course with modules covering a broad spectrum of content including basics of drugs and drug-related harms, harm reduction efforts including NSP and MAT, abscess prevention and management, overdose prevention and management, and behaviour change communication. PEs have access to relatively hidden PWID community spaces and provide health counselling, linkage to support organisations, information and other services to this vulnerable population.

For this study, PEs who were actively carrying out basic duties were chosen by the leadership at each organisation based on several factors including awareness and knowledge of HIV in the community and access to unique target populations (for instance, women who inject drugs may be more easily accessed by women PEs). Once identified, PEs underwent an intensive 1-day training to educate them on the practice and ethics of research, study procedures and their role in the study. PEs are supervised by clinic managers, who are all collaborators in the study. PEs participate in regular health education and harm reduction training and engage in quarterly sessions with study leadership where they present barriers and lessons learnt to the study team so that study-related issues can be addressed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are different for indexes and partners (table 1). Any interested individuals who are under the age of 18 years are referred to the site clinicians for routine counselling and harm reduction services.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Group | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Index |

|

|

| Partner |

|

None. |

IPV, intimate partner violence.

Index recruitment and enrolment

Enrolment began in March 2018. Clinicians at each site identify potential indexes using existing clinical data on known HIV-positive clients. Additionally, any client who tests positive for HIV during routine testing is invited to participate. Clinicians are employed by the sites and are trained clinical officers (COs) or midlevel providers. For this study, HIV rapid testing is performed by non-study COs and takes place as part of standard clinic procedures. All potential indexes are retested using HIV rapid tests (as per the national guidelines) to confirm HIV status prior to enrolment. If HIVpositive, either newly diagnosed or known to be positive, clinicians approach potential indexes with one of two strategies. Either the clinicians discuss the study directly with potential participants or engage PEs to find individuals and bring them to the study office if they are not regular clients at the site. Importantly, PEs are not told whether participants are being traced as an index or a partner, protecting the confidentiality of indexes’ HIV status.

Study staff health advisors (HAs) are the individuals responsible for conducting study procedures including notification of exposure, data collection, HIV and HCV testing and the coordination of APS efforts (figure 2). All HAs were trained and experienced in HTSs prior to working for the study, and many had previous experience working with PWID. All HAs underwent a week-long training course at the beginning of the study in which they learnt the basics and purpose of research, research ethics, study procedures, unique ethical and logistical issues to consider when working with PWID and other topics. All HAs also completed the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative course on Human Subjects Research and the Responsible Conduct of Research. HAs explain the benefits and rationale for providing APS, discuss the importance of learning more about HIV and HCV and describe the process of notifying partners without revealing the identity of the index. They ask participants to provide written informed consent for study participation, APS and future use of biological specimens and future contact for additional studies, using an iris-scanning biometric device to record a unique identifier for each participant, thus enabling the study team to confirm that a person does not enrol into the programme as an index more than once.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Indexes undergo a structured questionnaire administered by the HA using open data kit (ODK) software on tablet devices (ODK, 2017, Seattle, Washington, USA). Questionnaires cover a variety of topics including demographics, sexual and injecting behaviours, drug use history and HIV testing and history of engagement in HIV care. Participants are then asked to recall all of their sexual and injecting partners over the 3 years prior to enrolment, naming these partners one by one and assigning each partner a letter (‘A’, ‘B’ and so on). Sexual intercourse is defined as vaginal, oral or anal sex, and drug injecting partner is defined as a friend that you inject with frequently. Indexes are asked to give as much locator information as possible for each partner, including names (which may be nicknames), phone numbers and location of employment or residence. Locator information is written on a paper form for each partner. Indexes then complete a short ODK questionnaire about each partner mentioned, which includes information about the relationship between the index and the partner. Indexes who wish to notify partners themselves are given a 2-week window in which to do so, after which partners are contacted by study staff. Partners notified by indexes through passive referral are told to present to the study site for enrolment in the study, and mode of referral is recorded for each partner in the study.

Indexes then undergo rapid HCV antibody testing as part of routine study procedures. HAs conduct pretest and post-test counselling and ensure individuals who test positive are available for follow-up visits to discuss confirmatory HCV PCR testing and enrolling in a treatment programme administered by the Ministry of Health (MoH). All indexes then undergo phlebotomy with a sample of 10 mL of blood drawn for further testing (see “Laboratory Procedures”). Indexes receive 400 Kenya shillings (KES, equivalent to about $4) as compensation for travel and time spent in the study procedures.

PE-mediated ASPs and partner recruitment

For those partners who have phone numbers listed, HAs attempt phone communication first. However, the vast majority of partners mentioned by indexes do not have working cellular phones; therefore, with few exceptions, PEs locate and conduct the study’s first interaction in person with identified partners. PEs are given paper forms containing names and locator information for identified partners, and they verify that the names and locations provided on the locator form matches those of the person they have contacted. They are never told which index referred the team to each partner and that information is not listed on locator forms or any other accessible file. PEs then locate and approach potential participants in the community and inform them that they have been identified as an individual who might need to be seen in a clinic due to a health concern. When approaching a partner, PEs alert partners that the PEs are working with a research study and that the partner may have a health issue that should be addressed. The PEs then urge the partner to accompany them to a health facility for testing and possible enrolment in the study. Although PEs are trained using a standardised script (online supplemental appendix 1), they are encouraged to allow the conversation to progress naturally, responding to questions and concerns that may arise and urging partners to come to the site for further information. PEs do not notify partners of their exposure during initial contact for several reasons: (1) to protect the HIV status of indexes, PEs are not told whether they are recruiting an index or a partner and (2) PEs have not felt comfortable discussing HIV or HCV exposure with potential participants. Once PEs have notified potential participants of their possible eligibility, they then accompany interested individuals to the nearest research office, where the study’s HAs inform partners of their potential exposure to HIV and/or HCV (online supplemental appendix 2) and conduct informed consent. Informed consent includes consent to future use of biological specimens and future contact for additional studies. In the rare event that a potential participant does not agree to come to the study office, an HA returns to the site with the PE and notifies the individual of the exposure, and in the rare event that a potential participant agrees to come to the study office but does not want to enrol in the study, the HA notifies the individual of the exposure and encourages the individual to undergo testing for HIV and HCV outside of study procedures.

bmjopen-2020-041083supp001.pdf (28.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-041083supp002.pdf (25.5KB, pdf)

Partner enrolment

After informed consent and biometric identification, partners complete a structured questionnaire similar to that of indexes, administered by HAs on a handheld device using ODK software. Following the questionnaire, all partners undergo rapid antibody testing for both HIV and HCV. HTSs are provided in accordance with national HIV testing guidelines. Any partner found to be positive for either HIV or HCV antibodies undergoes a 20 mL blood draw. Those partners who test negative for both HIV and HCV are finished with study procedures at this time and are counselled on risk reduction measures and provided information about HIV and HCV prevention services before leaving the study site. All partners receive 400 KES (equivalent to about $4) as compensation for travel and time spent in the study procedures.

HIV-positive partners are invited to undergo screening as an index once data collection procedures for their partner enrolment are complete. If they meet eligibility criteria as an index, they may enrol as an index. Study procedures are slightly amended for indexes that have previously enrolled as partners. After undergoing informed consent and completing a short questionnaire that only includes questions that were not a part of the partner enrolment questionnaire, they complete the identification and data collection on each of their sexual and injection partners, identical to partner identification procedures for indexes described previously.

Laboratory procedures

Blood samples from both index and partner enrolment visits are collected in EDTA vacutainer tubes. Blood is mixed with the anticoagulant by inversion, and the anticoagulated blood is stored at room temperature at the sites for less than 4 hours. A motorcycle courier picks samples from each site daily and brings them to the University of Nairobi Pediatric Research Laboratory in Nairobi or the Malindi Sub-County Hospital Laboratory for coast sites. At each laboratory, samples are first used to prepare two Whatman 903 Protein Saver dried blood spot (DBS) cards with 50 µL of whole blood on each spot. Blood samples are then centrifuged and used to prepare 2–3 aliquots of 1 mL of plasma in labelled serum vials. Plasma aliquots and air-dried DBS cards (with desiccant in sealed ziploc bags) are then stored at −80°C and shipped on dry ice to the University of KwaZulu-Natal laboratory. There, samples undergo HIV and HCV viral load testing and amplification for sequencing.

Participant follow-up

All indexes and any partners who were positive for HIV or HCV complete a 6-month follow-up visit. HAs identify which participants are due for follow-up visits on a weekly basis and give PEs as list of these names. PEs then trace participants and bring them back to clinics where data collection procedures are conducted. PEs make several attempts to find participants in the community before considering them lost to follow-up.

Six-month visits involve a brief questionnaire covering questions on testing for HIV or HCV (if not infected with both on enrolment), enrolment in care and treatment, engagement in care and follow-up testing. The purpose of this visit is to assess whether engagement in care has changed following APS procedures, for both indexes and partners. We do not collect additional data from those lost to follow-up.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) monitoring

Given historical concerns that APS may increase one’s risk of experiencing IPV, all potential participants undergo screening for IPV before enrolment. IPV is defined as any physical, sexual or psychological harm inflected on a person by a current or former sexual partner. After answering a standardised set of six questions about physical, emotional and sexual IPV and the timing of any previous experience of IPV based on published screening tools reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,60 potential participants are classified as low, medium or high risk for IPV. Individuals are classified as at high risk for IPV if they report IPV within the last month. Any potential index who is classified as high IPV risk is excluded from study participation and provided with IPV counselling and resources. Any potential partner participant who is classified as high IPV risk is allowed to enrol but then receives special monitoring for IPV following enrolment.

Potential participants are classified as at moderate risk for IPV if they report: (1) IPV during their lifetime either from a current or past partner and/or (2) fear of IPV if they participate in the study. All index or partner participants classified as moderate IPV risk receive special monitoring for IPV following their enrolment in the study.

Potential participants are classified as at low risk for IPV if they report: (1) no IPV during their lifetime and (2) no fear of IPV if they participate in the study. These individuals undergo standard study procedures that include completing the baseline IPV case report form and a follow-up IPV case report to capture reports of any interim IPV.

Confidentiality and safety

Participants: all study procedures take place in private rooms at each study facility. To ensure the safety and confidentiality of indexes, PEs who are tasked with finding partners are blinded to the identity of the linked index through the use of partner locator forms that do not contain identifying information about the index participant. Locator forms do contain a printed barcode label that are then used by study staff to link the partner with the index who referred the partner.

Sexual partners are brought to independent facilities for enrolment rather than to centres that serve PWID, in order to further protect the identity of the index participant who referred them. The independent facilities are local healthcare clinics that serve the general population.

Peer educators: PEs have frequent interactions with police and can be victims of harassment or violence, both by police and by PWID. To reduce the risk of law enforcement troubles, PEs carry identification showing that they are working on a study being conducted by the MoH. Local law enforcement officials have also attended ongoing sensitisation trainings by the MoH and by organisations working with PWID.

Referrals to care

HIV counselling and care: participants are provided with their HIV test results in the context of post-test counselling and are then referred to available medical and psychosocial care and support facilities either within the research site or in close proximity to the research site or the participant’s home. Additionally, HIV-positive individuals are offered individual or group support sessions as available within each site.

HCV counselling and care: participants who test positive for HCV antibodies using rapid testing are provided with their HCV antibody test results in the context of pretest and post-test counselling. They are informed that they may have active HCV infection; however, further confirmatory testing must be done prior to establishing the diagnosis. Confirmatory PCR testing is done in batches of samples at our partnering laboratory at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and participants with active infection are later contacted for results and counselling. Turnaround time from enrolment to PCR result notification varies but is typically between 1 and 4 months. Once notified of their PCR results, those with active infection are paired with a PE at their site to ensure close contact is maintained. Study participants with active HCV infections will be eligible to receive free treatment with direct acting antivirals, which the Kenyan MoH has procured.

Data management

After each study visit, HAs review their work for omissions or errors, and all data are uploaded into the study database. Electronic data are stored securely in an encrypted database on servers using Open Data Kit Aggregate, within Kenya’s MoH. All errors or omissions identified at any step in the quality assurance/quality control process are revised by the staff member who originally completed the document. All additions and corrections are initialled and dated by the staff member who records the entry.

A link-log is separately encrypted to further ensure that data remain secure. Any data transferred to investigators or MoH are deidentified and encrypted during the process of transfer from the server. Each investigator maintains and stores secure, complete, accurate and current study records throughout the study. A database manager performs regular data cleaning and resolves any discrepancies that occur. Study sites also conduct quality control and quality assurance procedures. All coinvestigators have access to the final dataset, and this is not limited by contractual agreements. Study data will be available on request at the completion of the study.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest to assess the success of the APS intervention are: (A) number of sexual and injection partners tested for HIV and HCV through APS, identified by each index participant over the course of the study period; (B) number of sexual and injection partners newly testing positive for HIV and HCV, per index participant; (C) number of known HIV or HCV cases identified through APS who are not engaged in care; (D) number of index and partner participants with HIV and/or HCV infection who are linked to care; and (E) number of index and partners with HIV and/or HCV infection who remain in care and are receiving appropriate treatment at 6 months after testing positive. Secondary outcomes are linked to inclusion in phylogenetic clusters identified as high risk for onward transmission of HIV and HCV.

Sample size

We are enrolling 1000 HIV-positive indexes and their sexual and injecting partners. Based on HCV data from MoH and our preliminary results, we estimate that 20% of PWID with HIV will be coinfected with HCV and that each index will identify on average two partners who will accept HIV and HCV testing, 20% of whom will be HIV positive and 20% of whom will be HCV infected. Thus, with provision of APS to 1000 HIV-positive indexes and testing of 2000 partners, we will identify an estimated 600 indexes and partners infected with HCV and 400 HIV-positive partners. This study was designed to have high precision in estimating the prevalence of HIV and HCV infection among partners, providing valuable input for modelling the impact of APS in the population. For an observed HIV or HCV prevalence of 10% among partners, precision is estimated at 1.9%; with an observed HIV or HCV prevalence of 30% among partners, precision is estimated at 2.9%.

Statistical methods and analysis

To determine efficacy of the APS intervention, we will use generalised estimating equations (GEEs) models with a Poisson link using the following variables and offsets: (1) rate of HIV and HCV testing of partners: number of individuals tested for HIV or HCV, offset by the number of partners located with locator information provided by the index participant; (2) prevalence of HIV and HCV infection: number of individuals identified as HIV or HCV positive, offset by the number of individuals who were HIV tested; and (3) rate of linkage to HIV and HCV care: individuals who test HIV or HCV positive and link to care, offset by the total number of individuals who test HIV or HCV positive.

Additionally, using both GEE and phylogenetic analysis, we will determine the following: (1) identifiable and individual risk factors linked to high rates of HIV and HCV transmission, (2) risk factors linked to both needle sharing and sexual transmission and (3) identification of transmission clusters among PWID for both HIV and HCV.

Phylogenetic analysis

HIV and HCV gene sequencing are attempted for all study participants who test positive for either virus. Sequencing will be performed at the KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa. For HIV, we will subsequently combine our data with additional, publicly available, HIV sequences from Kenya and perform phylogenetic and phylodynamic analyses to describe patterns and rates of viral transmission among KPs in Kenya and identify traits associated with relative infectiousness. For HCV, we will use phylogenetic methods to characterise the modes and risk factors for onward transmission among PWID.

Ethics and dissemination

General ethical considerations

This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and has ethical approval from both the University of Washington Human Subjects Division and the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Committee. It also has approval from Kenya’s National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation.

There are a number of potential risks to participants. Risks of conducting APS include psychological distress, social or economic hardship, criminal penalties and loss of privacy and/or confidentiality. Study procedures, including confidentiality and counselling procedures, are specifically designed to minimise these risks to participants. While IPV has the potential to cause harm, it has not increased in other US or African studies when this intervention has been implemented in the general population.25 61 62 We recognise that risks may be different when implementing APS among KPs, and study staff are highly trained in counselling about risk behaviours, implications of testing HIV-positive and protecting confidentiality to avoid potential social harms. In addition, staff have undergone extensive training on IPV counselling and ensure that resources have been identified in all sites so we can safely refer participants who report abuse or are concerned for their safety. Participants reporting moderate IPV are monitored as described in “Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) monitoring” above; they are counselled and referred for services if IPV is reported at any of these follow-up visits.

A safety monitoring board composed of researchers and policy makers in both Kenya and the USA reviews study safety data twice per year. The board monitors enrolments, deaths, loss to follow-up, adverse events, including social harms, and IPV monitoring data and makes recommendations regarding study procedures.

Ethical considerations surrounding the use of biometric identification systems among KPs in Kenya have been discussed extensively.63 Despite early opposition from the Key Populations Consortium and other organisations to the government’s use of fingerprint-based biometric data collection, the organisations and individuals working with PWID communities continued to report no opposition to iris scanning for research purposes among PWID. In November 2019, Kenya passed the Data Protection Bill, rendering it legal to collect biometric data as long as the use of such data does not violate the subjects’ rights.64 The use of biometrics is now standard practice in many research and clinical settings and has been found to be acceptable to participants.65 Our participants have not reported any concerns, fears or hesitations regarding the use of an iris scanning biometric identification system.

Dissemination plan

Results from the study and changes to the study are presented on an ongoing basis at Kenya’s quarterly MoH harm reduction and KP technical working group meetings and discussed at biannual meetings by the CAB that was established for this study. Our study team includes several collaborators from the MoH. Ongoing study analyses are also presented at national conferences annually. Additionally, study results are presented in at least one international conference per year. Finally, the study team reviews data on a weekly basis, and any changes in data trends or other concerns are discussed directly with the organisations through which study procedures take place.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CF and JH conceived of the study; AM-W, BG, BC, MD, PM, BSi, JH and CF contributed to the study design and data collection structure; AM-W, LM, DB, BSa, BC, JS, PC, HM, RB, PM, SM, EW, TDO, BSi, JH and CF contributed to data collection; AM-W, LM, BG, DB, BSa, PC, HM, RB, SM, EW, TDO, NL-B, JH and CF contributed to data analysis and dissemination; AM-W, BG, JH and CF wrote the manuscript; all authors reviewed the manuscript for content.

Funding: This work was supported by the Division of AIDS, National Institute of Drug Abuse, grant number R01 DA043409. 301 North Stonestreet Ave, Bethesda, MD 20892. +1 301-443-1124.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Levi J, Raymond A, Pozniak A, et al. Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000010. 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS . 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic, 2014. Available: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf

- 3.Staveteig S, Croft TN, Kampa KT, et al. Reaching the 'first 90': Gaps in coverage of HIV testing among people living with HIV in 16 African countries. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186316. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP) . Preliminary KENPHIA 2018 report, 2020. Available: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/KENPHIA-2018_Preliminary-Report_final-web.pdf

- 5.Brodish P, Singh K, Rinyuri A, et al. Evidence of high-risk sexual behaviors among injection drug users in the Kenya place study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;119:138–41. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet 2008;372:1733–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National AIDS Control Council, National AIDS and STI Control Programme , 2014. Available: https://hivpreventioncoalition.unaids.org/country-action/kenya-hiv-prevention-revolution-road-map-june-2014/ [Accessed 08/03/2021].

- 8.Kurth AE, Cleland CM, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Hiv prevalence, estimated incidence, and risk behaviors among people who inject drugs in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70:420–7. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ndetei DM. A sudy on the linkages between drug abuse, injecting drug use and HIV/AIDS in Kenya: a rapid situation assessment.. Nairobi: University of Nairobi; 2004. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/65170?show=full [Accessed 08/03/21]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odek-Ogunde M, Okoth F, Lore W, et al. Seroprevalence of HIV, HbC and HCV in injecting drug users in Nairobi, Kenya: World Health organization drug injecting study phase II findings. The XV International AIDS Converence; 2004, Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National AIDS Control Council . Kenya HIV estimates report, 2018. Available: https://nacc.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/HIV-estimates-report-Kenya-20182.pdf

- 12.Tun W, Sheehy M, Broz D, et al. Hiv and STI prevalence and injection behaviors among people who inject drugs in Nairobi: results from a 2011 bio-behavioral study using respondent-driven sampling. AIDS Behav 2015;19 Suppl 1:24–35. 10.1007/s10461-014-0936-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lizcano J. Testing and linkage to care for injecting drug users. 11th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; 2016, Fort Lauderdale, FL, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Githuka G, Hladik W, Mwalili S, et al. Populations at increased risk for HIV infection in Kenya: results from a national population-based household survey, 2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66 Suppl 1:S46–56. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akiyama MJ, Cleland CM, Lizcano JA, et al. Prevalence, estimated incidence, risk behaviours, and genotypic distribution of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs accessing harm-reduction services in Kenya: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:1255–63. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30264-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muasya T, Lore W, Yano K, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and its genotypes among a cohort of drug users in Kenya. East Afr Med J 2008;85:318-25. 10.4314/eamj.v85i7.9649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartonjo G, Oundo J, Ng'ang'a Z, Ng’ang’a Z. Prevalence and associated risk factors of transfusion transmissible infections among blood donors at regional blood transfusion center Nakuru and Tenwek mission Hospital, Kenya. Pan Afr Med J 2019;34:31. 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.31.17885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loarec A, Carnimeo V, Molfino L, et al. Extremely low hepatitis C prevalence among HIV co-infected individuals in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2019;33:353–5. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Litwin AH, Jost J, Wagner K, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized pragmatic trial of patient-centered models of hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: the hero study. Contemp Clin Trials 2019;87:105859. 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treloar C, Hull P, Dore GJ, et al. Knowledge and barriers associated with assessment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Rev 2012;31:918–24. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enkelmann J, Gassowski M, Nielsen S, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and low level of awareness among people who recently started injecting drugs in a cross-sectional study in Germany, 2011-2014: missed opportunities for hepatitis C testing. Harm Reduct J 2020;17:7. 10.1186/s12954-019-0338-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day E, Hellard M, Treloar C, et al. Hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: challenges and recommendations for action within a health systems framework. Liver Int 2019;39:20–30. 10.1111/liv.13949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medicins du Monde . Our activities in Kenya, 2020. Available: https://www.medecinsdumonde.org/en/countries/africa/kenya

- 24.Cherutich P, Kurth A, Lizcano JA. Integration of hepatitis C treatment services with harm reduction service centers for people who inject drugs in Kenya: experience from test and link to care for injecting drug users study. International Viral Hepatitis Elimiation Meeting, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalal S, Johnson C, Fonner V, et al. Improving HIV test uptake and case finding with assisted partner notification services. AIDS 2017;31:1867–76. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahabuka C, Plotkin M, Christensen A, et al. Addressing the first 90: a highly effective partner notification approach reaches previously undiagnosed sexual partners in Tanzania. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2551–60. 10.1007/s10461-017-1750-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherutich P, Golden MR, Wamuti B, et al. Assisted partner services for HIV in Kenya: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e74–82. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30214-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotkin M, Kahabuka C, Christensen A, et al. Outcomes and experiences of men and women with partner notification for HIV testing in Tanzania: results from a mixed method study. AIDS Behav 2018;22:102–16. 10.1007/s10461-017-1936-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma M, Smith JA, Farquhar C, et al. Assisted partner notification services are cost-effective for decreasing HIV burden in Western Kenya. AIDS 2018;32:233–41. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis SE, Schoenbach VJ, Weber DJ, et al. Results of a randomized trial of partner notification in cases of HIV infection in North Carolina. N Engl J Med 1992;326:101–6. 10.1056/NEJM199201093260205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers RS, Feldacker C, Cesár F, et al. Acceptability and effectiveness of assisted human immunodeficiency virus partner services in Mozambique: results from a pilot program in a public, urban clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:690–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, et al. Hiv partner notification is effective and feasible in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for HIV treatment and prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;56:437–42. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318202bf7d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, et al. Predicting partner HIV testing and counseling following a partner notification intervention. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1148–55. 10.1007/s10461-011-0094-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . WHO recommends assistance for people with HIV to notify their partners, 2019. Available: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/who-partner-notification-policy/en/

- 35.Quinn C, Nakyanjo N, Ddaaki W, et al. Hiv partner notification values and preferences among sex workers, fishermen, and mainland community members in Rakai, Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3407–16. 10.1007/s10461-018-2035-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rane V, Tomnay J, Fairley C, et al. Opt-Out referral of men who have sex with men newly diagnosed with HIV to partner notification officers: results and yield of sexual partners being contacted. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:341–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halkitis PN, Kupprat SA, McCree DH, et al. Evaluation of the relative effectiveness of three HIV testing strategies targeting African American men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York City. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2011;42:361–9. 10.1007/s12160-011-9299-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy JA, Fox SE. The outreach-assisted model of partner notification with IDUs. Public Health Rep 1998;113 Suppl 1:160–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malik M, Jamil MS, Johnson CC, et al. Integrating assisted partner notification within HIV prevention service package for people who inject drugs in Pakistan. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22 Suppl 3:e25317. 10.1002/jia2.25317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeBeck K, Cheng T, Montaner JS, et al. Hiv and the criminalisation of drug use among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e357–74. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30073-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.United Nations, Office on Drugs and Crime . World drug report 2016. Geneva: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molinaro S, Resce G, Alberti A, et al. Barriers to effective management of hepatitis C virus in people who inject drugs: evidence from outpatient clinics. Drug Alcohol Rev 2019;38:644–55. 10.1111/dar.12978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips KT. Barriers to practicing risk reduction strategies among people who inject drugs. Addict Res Theory 2016;24:62–8. 10.3109/16066359.2015.1068301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heath AJ, Kerr T, Ti L, et al. Healthcare avoidance by people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand. J Public Health 2016;38:e301–8. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frost SDW, Pillay D. Understanding drivers of phylogenetic clustering in molecular epidemiological studies of HIV. J Infect Dis 2015;211:856–8. 10.1093/infdis/jiu563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brenner BG, Wainberg MA. Future of phylogeny in HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63 Suppl 2:S248–54. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacka B, Applegate T, Krajden M, et al. Phylogenetic clustering of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Hepatology 2014;60:1571–80. 10.1002/hep.27310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grabowski MK, Lessler J, Redd AD, et al. The role of viral introductions in sustaining community-based HIV epidemics in rural Uganda: evidence from spatial clustering, phylogenetics, and egocentric transmission models. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001610. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worobey M, Gemmel M, Teuwen DE, et al. Direct evidence of extensive diversity of HIV-1 in Kinshasa by 1960. Nature 2008;455:661–4. 10.1038/nature07390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Oliveira T, Pillay D, Gifford RJ, et al. The HIV-1 subtype C epidemic in South America is linked to the United Kingdom. PLoS One 2010;5:e9311. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes GJ, Fearnhill E, Dunn D, et al. Molecular phylodynamics of the heterosexual HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000590. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hué S, Clewley JP, Cane PA, et al. Investigation of HIV-1 transmission events by phylogenetic methods: requirement for scientific rigour. AIDS 2005;19:449–50. 10.1097/01.aids.0000161778.15568.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dennis AM, Hué S, Hurt CB, et al. Phylogenetic insights into regional HIV transmission. AIDS 2012;26:1813–22. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283573244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ambrosioni J, Junier T, Delhumeau C, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the molecular epidemiology of newly diagnosed HIV infections. AIDS 2012;26:2079–86. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835805b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kouyos RD, Rauch A, Böni J, et al. Clustering of HCV coinfections on HIV phylogeny indicates domestic and sexual transmission of HCV. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:887–96. 10.1093/ije/dyt276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fisher M, Pao D, Brown AE, et al. Determinants of HIV-1 transmission in men who have sex with men: a combined clinical, epidemiological and phylogenetic approach. AIDS 2010;24:1739–47. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ac9e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy J-P, et al. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2007;195:951–9. 10.1086/512088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kramer MA, Cornelissen M, Paraskevis D, et al. Hiv transmission patterns among the Netherlands, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles: a molecular epidemiological study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011;27:123–30. 10.1089/aid.2010.0115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henley C, Forgwei G, Welty T, et al. Scale-Up and case-finding effectiveness of an HIV partner services program in Cameroon: an innovative HIV prevention intervention for developing countries. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:909–14. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 410572008-001. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monroe‐Wise A, Maingi Mutiti P, Kimani H, et al. Assisted partner notification services for patients receiving HIV care and treatment in an HIV clinic in Nairobi, Kenya: a qualitative assessment of barriers and opportunities for scale‐up. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22. 10.1002/jia2.25315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goyette MS, Mutiti PM, Bukusi D, et al. Brief report: HIV assisted partner services among those with and without a history of intimate partner violence in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:16–19. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.KELIN and the Kenya Key Populations Consortium . “Everyone said no:” biometrics, HIV and human rights – A Kenya case study. KELIN, 2018. Available: https://www.kelinkenya.org/everyonesaidno/

- 64.Gathura G. Biometrics system for identifying people living with HIV ready. The standard, 2019. Available: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001349675/biometrics-system-for-identifying-people-living-with-hiv-ready

- 65.Anne N, Dunbar MD, Abuna F, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an iris biometric system for unique patient identification in routine HIV services in Kenya. Int J Med Inform 2020;133:104006. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.104006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041083supp001.pdf (28.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-041083supp002.pdf (25.5KB, pdf)