Abstract

Thirty-five gem-quality turquoise samples with various colours were investigated using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Sample chemical and spectral analyses indicate that Fe3+ contributes to green hue of turquoise, whose absorption band exhibits a bathochromic shift from 426 to 428 nm with increasing V content in the solid-solution series turquoise-chalcosiderite. V3+ enhances absorption in the blue and orange regions, and Cr3+ increases absorption in the green region, both of which are responsible for the vivid greenish yellow in faustite. Substitutions of Al by medium-sized trivalent cations (primarily Fe3+ and V3+) enhance polarity of the phosphate group (PO4)3−, resulting in strong absorption in the infrared spectra for analogues of turquoise. The reflectivity ratio (ROH) of the double absorption peaks at 781 and 833 cm−1 allows faustite to be distinguished from turquoise and chalcosiderite, with a value greater than 1, while V-rich faustite only has a single absorption peak at 798 cm−1. An increasing amount of absorbed water contributes to blue chroma in turquoise and has a negative effect on lightness based on the CIE 1976 L*a*b* colour system. Loose turquoise with a low specific gravity tends to display greater colour differences with a significant decrease in lightness.

Keywords: turquoise, ED-XRF, UV–Vis spectra, FTIR, colour difference

1. Introduction

Turquoise is one of the most well-known and ancient types of jade, prevalent in Chinese literature, religion, politics and arts (e.g. jewellery) [1]. Turquoise deposits are well developed in the United States [2,3], Egypt [4], Iran [5] and China, where turquoise in China is mostly mined in the Hubei and Anhui provinces. The mineralization of turquoise commonly occurs in the tectonic fracture zone within thick- and thin-bedded siliceous and carbonaceous-siliceous slates, while the gem-quality turquoise is almost formed by exogenous leaching [6].

Turquoise, a hydrated copper aluminium phosphate, is a main mineral in the turquoise group which consists of at least six isostructural end-members, including faustite (the rare Zn analogue of turquoise) and chalcosiderite (the Fe analogue of turquoise) [7]. A complex chemical composition produces a wide colour range in turquoise [8]. The general formula for the turquoise group can be written as A0−1B6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O with Cu2+ or Fe2+ as the most popular constituents at the A-position and Al3+ and Fe3+ at the B-position. However, Zn2+ or Ca2+ can be present at the A-position and V3+ or Cr3+ can occur at the B-position in some rare turquoises [9]. Previous research suggests that the chemical composition, structure compactness and adsorbed water content of turquoise are the main internal factors affecting its colour—explained by crystal field theory and charge transferring [10]. Turquoise blue, for example, comprises Cu octahedra in crystalline turquoise, and a colour transition from blue to yellow is determined by Fe content [11]. The substitution of Al by Fe3+ results in a yellow hue and an upward trend in Fe content can create brown turquoise [12]. However, there are other trace elements found in turquoise, which may affect the colour of turquoise. Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis) probes the absorption behaviours of different metal cations, and is an effective technique in establishing the impact of transition metal cations on a gem's colour. UV–Vis lends itself to the study of colours in various gemstones, such as emerald [13], variscite [14], demantoid [15], uvarovite [16] and turquoise [6,17].

Currently, several techniques can be applied to investigate the chemical composition of turquoise. Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and multi-receiver inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS) are used for the isotopic analysis of hydrogen, copper, strontium and lead in turquoise, distinguishing the provenance of turquoise artefacts [18]. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry (LA-ICP-AES) is used to study the geochemical characteristics of trace elements and rare-earth elements in modern turquoise, to determine its origin [19]. Electron microprobe analysis (EMPA) is used to quantitatively analyse the main elements and rare earth elements in turquoise, especially for the turquoise of various colours [20]. Compared with traditional methods, energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) is an advanced and non-destructive technique, which is widely applied in chemical analyses for mineralogy [21], materials science [22], geology [23], environmental science [24] and gemmology. ED-XRF is similarly suitable for the study of turquoise [25–27]. Several scholars have used LA-ICP-MS to measure the element content of uniformly coloured turquoise, establishing a standard working curve in order to predict the element content of unknown turquoise using ED-XRF [28]. In addition, ED-XRF can be used to quantitatively or semi-quantitatively analyse differences in the element content of turquoise and its imitators, allowing the identification of natural turquoise [29]. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a valuable technique in studying hydrated minerals, and is sensitive to the hydroxyl (OH) group; this type of spectroscopy easily distinguishes OH with H2O molecules in the structure. Moreover, FTIR is well used to determine the origin of natural turquoise [30–32].

The type and content of water in turquoise can significantly influence its physical properties, especially its colour. Three types of water are found in turquoise, including hydroxyl groups with strong hydrogen bonds (Al–OH), [Cu(H2O)4]2+ with relatively weak hydrogen bonds and adsorbed water in pores or micro-fractures, whose content generally influences colour [33]. The content of adsorbed water in natural turquoise is usually less than 2% and varies as a function of environmental humidity [34]. However, it is poorly understood what role an increase in absorbed-water content plays in turquoise colour, and most previous research is based on naked-eye observation, lacking quantitative analysis. Therefore, we make good use of colorimetry theory to design a water immersion experiment.

The CIE 1976 L*a*b* uniform colour system is the most popular system for colour measurement and analysis, currently recommended by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) [35–38]. Serving as the foundation for the quantitative characterization of colour, this colour system possesses good colour uniformity, where the colour difference observed by the naked eye is positively correlated with that calculated by colorimetric coordinates in this system [39,40]. The colour system is widely applied in the study of gem's colour, including jadeite-jade [41–43], peridot [44,45], tourmaline [46], amethyst [47] and diamond [48]. The formula CIE DE2000 can be used to express colour difference quantitatively and effectively [49–51]. Therefore, this formula was applied to calculate the colour differences in turquoise caused by water immersion, as well as study the impact of absorbed water on turquoise colour.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Material

We collected 35 pieces of gem-quality turquoise samples from China, ranging from 0.20 to 0.40 ct, displaying a colour transition from blue to greenish yellow. Fifteen samples of turquoise had a round-cabochon shape, while the others had a round-plate shape. All were well polished, with a smooth, clear surface, conducive to chemical and spectral investigation. Some of the samples are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The top turquoise samples possess pure blue with slight colour variation. The bottom 15 samples display a continuous colour transition from blue to yellow-green.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. ED-XRF

Micro-area chemical compositions were measured using an EDX-7000 energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, with the following test conditions: atmosphere, oxide; a voltage of 50 kV; 108 µA; 30% DT; and a 3 mm collimator. Each sample was prepared as single block, whose tested area was a circle with a diameter of 3 mm.

2.2.2. UV–Vis spectroscopy

Absorption spectra in the UV–Vis range were recorded using a UV-3600 UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The test conditions were described as follows: the spectral range, 300–900 nm; the scanning speed, medium; the sampling interval, 0.5 s; the scanning mode, single, reflection. Each sample was prepared as single block, with a polished, smooth surface.

2.2.3. Infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy was conducted using a Tenstor 27 Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer. The measurement parameters were as follows: the wavenumber range, 2000–400 cm−1; the voltage, 210–230 V; the frequency, 50–60 Hz; reflection method. The sample states were the same as above.

2.2.4. Colorimetric analysis

Turquoise colour was quantified using an X-Rite SP62 portable spectrophotometer, which collects reflective signals on the turquoise surface. The measurement conditions were as follows: the CIE standard illumination, D65; the reflection, SCI; the observer's view, 10°; the spectral range, 400–700 nm; the measurement time, less 2.5 s; the voltage, 220 V; and the frequency, 50–60 Hz. The final colour data were averaged by three times testing. The tested area of a single sample was a circle with a diameter of 6 mm.

2.2.5. Uniform colour system

The colour system comprises a three-dimensional spherical colour space, with colorimetric coordinates (a* and b*) in the horizontal direction and lightness (L*) in the vertical direction [35]. Lightness represents a colour variation between darkest black (L* = 0) and lightest white (L* = 100), and a growth in lightness value means that the colour becomes brighter [38]. The colorimetric coordinate a* describes a colour variation from red (+a*) to green (−a*), while the colorimetric coordinate b* describes a colour variation from yellow (+b*) to blue (−b*) [36]. Chroma (C*) represents a saturation variation of single colour (e.g. blue), between lightest blue (C* = 0) and deepest blue (C* = 100). A colour with high chroma is more brilliant and intensive [38]. Hue angle (ho) varies from 0 to 2π, representing a series of continuous colour variation from red, yellow, green, blue to purple [36]. All the colour parameters are psycho-physical parameters without unit. C* and ho can be calculated using a* and b* as follows:

| 2.1 |

and

| 2.2 |

To calculate the colour difference in turquoise caused by increasing absorbed-water content, we use the CIE DE2000 (ΔE00) formula; this improves visual uniformity to compare with CIE L*a*b* [50]. ΔE00 calculates colour differences more precisely in the green-blue area and the formula is as follows:

| 2.3 |

where ΔL*, ΔC* and ΔH* are the differences in lightness, chroma and hue angle. RT is a conversion function that reduces the interaction between chroma and hue angle in the blue area. SL, SC and SH are functions that calibrate for the absence of visual uniformity in the CIE L*a*b* formula. KL, KC and KH are correction parameters for the experimental environment (KL = 1, KC = 1, KH = 1). The CIE DE2000 (1 : 1 : 1) was chosen, as it calculates more accurately colour difference.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical composition analysis

ED-XRF can be used to quickly detect the content of most elements in turquoise. A quantitative analysis of the chemical composition of 35 turquoise samples based on FP standard curve shows turquoise oxide content to be the following (table 1): w(P2O5) ∈ (32.827, 45.547), w(Al2O3) ∈ (22.100, 32.437), w(CuO) ∈ (1.403, 22.491), w(Fe2O3) ∈ (0.621, 15.192), w(ZnO) ∈ (0.089, 8.296), where w(Fe2O3) represents the total iron content detected in turquoise. The blue turquoise is rich in copper, whose w(CuO) ranges from 18.530% to 22.491% with an average of 20.008%. Fe-rich and Zn-rich samples are identified as ‘chalcosiderite’ and ‘faustite’, respectively.

Table 1.

The ED-XRF data of turquoise samples.

|

Turquoise is characterized by a triclinic structure (figure 2). Various site nomenclatures have been used to investigate the crystal structure and spectra of the turquoise group, dependent on chemical compositions. Here, we use a more general site nomenclature to explain the position of different metal cations, avoiding phrases such as ‘Fe3+ occupying an Al site’ [8]. The turquoise group structurally consists of distorted XO6 octahedra, MO6 octahedra and PO4 tetrahedra, where the X site is occupied by medium-sized divalent cations (e.g. Cu2+ and Zn2+) and the P site is occupied by phosphorus. The MO6 octahedra have three sites (M1–M3) occupied by small trivalent cations (primarily Al3+, Fe3+ and V3+). Therefore, the turquoise group is also expressed as X(M1M2M3)6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O (X = A, M = B). Pairs of edge-sharing M1 and M2 octahedra are linked through sharing O2− corners with pairs of PO4 tetrahedra to form chains extending along the b-direction. These chains are linked in the a- and c-directions through sharing O2− corners with M3 octahedra to further combine with X octahedra sharing edges with the M1 and M2 octahedra. Non-edge sharing with M1 and M2 octahedra results in difference in the local stereochemistry of the M3 octahedra. The heteropolyhedral framework is further strengthened by hydrogen bonds networks in three dimensions [7].

Figure 2.

The crystal structure of turquoise; X octahedra are shown in blue, P tetrahedra are shown in yellow, M1 and M2 octahedra are shown in green and M3 octahedra are shown in orange; hydrogen bonds are omitted for clarity. OH and H2O groups are shown as red and violet circles, respectively (referring from Abdu et al. [8]).

To analyse the chemical composition of turquoise with various colours, 35 turquoise samples were divided into six groups based on five centres of ho (105°/135°/165°/195°/225°) [52], including blue ho ∈ (215.99, 223.70), greenish blue ho ∈ (187.99, 192.59), bluish green ho ∈ (177.45, 180.98), green ho ∈ (158.64,169.39), yellowish green ho ∈ (137.54, 140.79) and greenish yellow ho ∈ (116.47, 130.45). Based on colour nomenclature, we know that blue-green includes greenish blue and bluish green, and yellow-green includes yellowish green and greenish yellow. Cu content, Fe content and Zn content are analysed by box chart (figure 3a), where the blue group is high in Cu and extremely low in Fe and Zn. The w(CuO) in green turquoise is significantly lower than that in blue turquoise, which varies slightly, reaching its lowest value in greenish yellow faustite. There exists a high Fe content in green and yellowish green turquoise, which gradually decreases with increasing blue and yellow hue. Because Zn is a rare element, only faustite is rich in Zn, with w(ZnO) > w(CuO), negatively correlated with the hue angle of turquoise. The results indicate that w(Fe2O3) is poor correlated with w(CuO) in all samples, indicating no obvious substitution of Cu by Fe2+ in the crystal structure of turquoise.

Figure 3.

(a) Box chart of Cu content, Fe content and Zn content in turquoise (classified in six hue groups). w(CuO) is shown in blue, w(Fe2O3) is shown in green and w(ZnO) is shown in orange. (b) w(Al2O3) versus w(Fe2O3) of the ED-XRF data in the green-hue turquoise, where the discrete grey points are due to the substitution of Al by V3+ and Cr3+.

Fe-rich turquoise has a green hue. The empirical expression between Fe content and Al content is as follows (figure 3b):

| 3.1 |

where r represents Pearson's correlation coefficient, describing the correlation between two variables. R2 represents the determination coefficient, reflecting the variability percentage of the dependent variable. The results indicate that w(Fe2O3) is significantly negatively correlated with w(Al2O3), which means that substitution of Al by Fe3+ results in the solid-solution series turquoise-chalcosiderite: Cu(Al,Fe3+)6(PO4)4(OH)8 · 4H2O. However, w(Cr2O3) and w(V2O5) are detected in green-hue turquoise, which may also result in a decreasing Al content.

Partial correlation analysis is effective in analysing the correlations among different variables when taking control of a relative variable. Fe3+, V3+ and Cr3+ may replace with Al3+ in the crystal structure of turquoise. Since w(V2O5) and w(Cr2O3) are extraordinarily lower than w(Fe2O3), we choose w(Fe2O3) as a control variable to examine the correlation between Cr–V content and Al content. A partial correlation analysis of Al–V–Cr content shows that both w(V2O5) and w(Cr2O3) have a good partial correlation with w(Al2O3), which explains the discrete grey points in figure 3b. The substitution of Al by V3+ and Cr3+ results in lower value of w(Fe2O3)/w(Al2O3). The trivalent metal cations, including Fe3+, V3+ and Cr3+, show representative absorption in the UV–Vis spectra, which contributes to the green hue in turquoise.

3.2. UV–Vis spectra

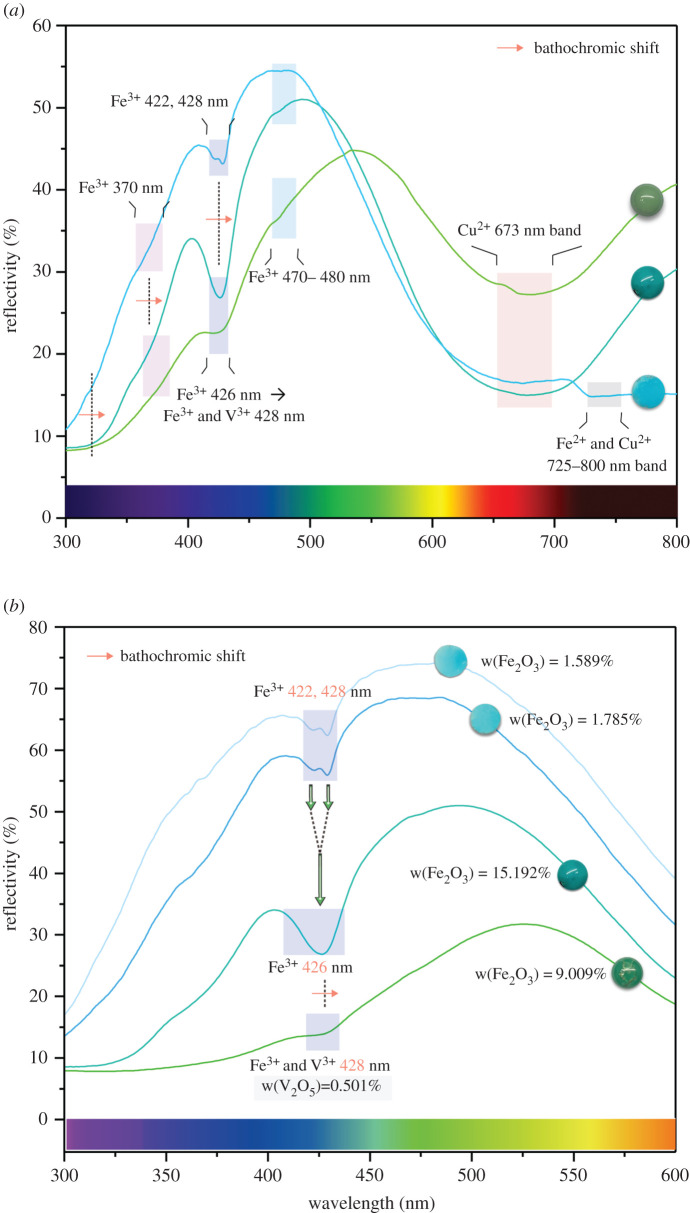

UV–Vis reflective spectra can accurately illustrate absorption characteristics of transition metal cations in turquoise. For Cu-rich turquoise (figure 4a), the absorption band in the orange-red region occurs around 673 nm due to the d–d electron transition of Cu2+ [6], and it can extend to 800 nm, as it combines with the weak absorption band caused by Fe2+. In addition, the double absorption peaks at 422 and 428 nm in the violet-blue region are caused by the electron transition of Fe3+ (6A1 → 4E and 4A1(4G)), while the weak absorption band in the ultraviolet region of 370 nm is caused by the Fe3+ electron transition (6A1 → 4E(4D)) and charge transferring from O2− to Fe3+ [17]. Increasing Fe content leads to an enlargement of the peak area at 428 nm and an enhancement in the resolution of the double peaks.

Figure 4.

(a) UV–Vis spectra of the solid-solution series turquoise-chalcosiderite, where the red arrow means that the absorption band has a bathochromatic shift. (b) UV–Vis spectra of turquoise in the 300–600 nm region, reflecting that the double absorption peaks merge into single peak at 426 nm, which shifts to 428 nm, with increasing V content.

For turquoise and chalcosiderite, the double peaks at 422 and 428 nm finally merge into a strong narrow band at 426 nm, reflecting a bathochromic shift from 426 to 428 nm before decreasing in absorption strength with increasing V content (figure 4b). The samples undergo a colour transition from blue to green in the process. The absorption band near 370 nm broadens, reflecting a bathochromic shift with increasing Fe content. The weak band in the blue region at 470–480 nm is due to the special Fe3+ lattice position [6], contributing to the yellow hue of turquoise. The results indicate that Fe and V trivalent cations can work together to enhance absorption in the violet and blue-violet regions, and are responsible for a blue-to-green transition.

Overall, the absorption reflectivity at 428 nm is negatively correlated with the lightness of turquoise and has no obvious correlation with Fe content, indicating that turquoise with high lightness has high reflectivity at 428 nm peak, which can be expressed as

| 3.2 |

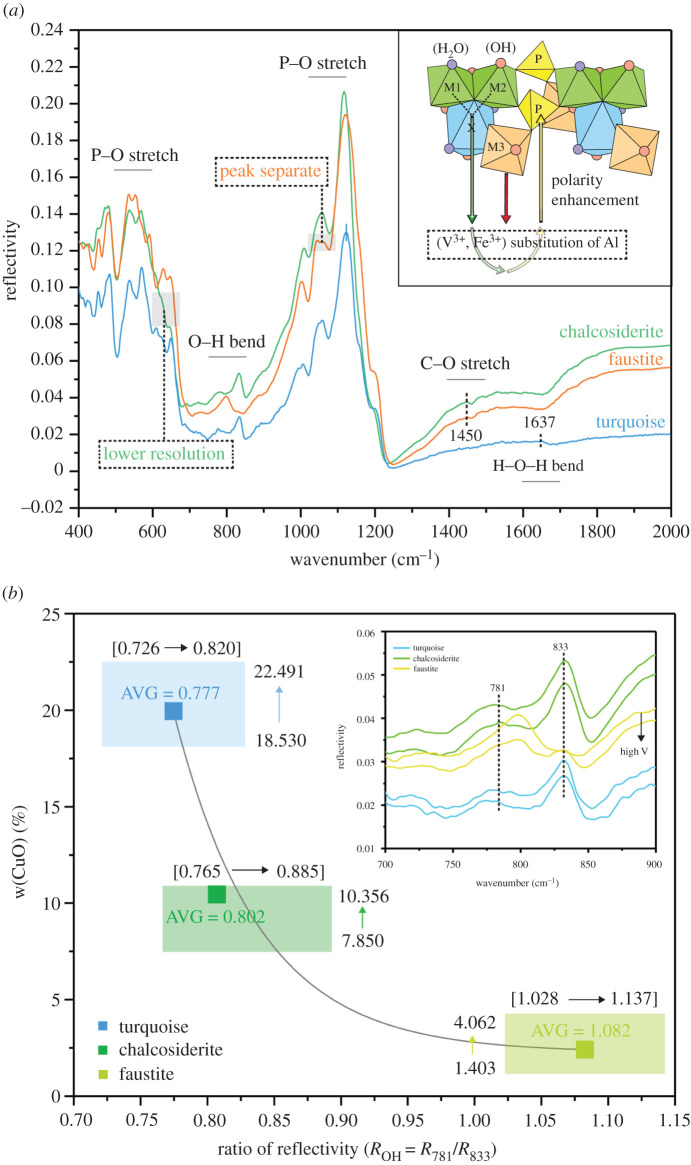

For faustite, there is no obvious absorption arising from Zn in the UV–Vis reflective spectra. The substitution of Cu by Zn2+ results in a decrease in Cu content and reduces absorption in the orange-red region to produce a hypochromic effect on blue. The electron transition of V3+ produces two absorption bands in the orange (620 nm) and violet-blue regions (420–460 nm) [13]. The band in the violet-blue region completely covers the absorption peaks at 422 and 428 nm derived from the Fe-electron transition, and broadens with increasing V content. Small levels of Cr in faustite can generate a narrow absorption band in the green region of 568 nm, and work with Cu to produce a broad absorption band in the red region of 683 nm [14]. The results indicate that Zn2+ suppresses the colour blue in turquoise, V3+ enhances absorption in the violet, blue and orange regions, and Cr3+ enhances absorption in the red and green regions, all of which works together to form the vivid greenish yellow in faustite (figure 5).

Figure 5.

UV–Vis spectra of faustite, where the red arrow means that the absorption band has a bathochromatic shift.

A stepwise regression method is often used to screen out variables with significant correlation and to judge the contributions of independent variables to dependent variables [53]. Therefore, we used this method to study the contributions of colour-causing metal elements (Cu, Fe, Zn, V and Cr) to b* (the colorimetric coordinate) in turquoise and to explain which element more sensitively influences the hue variation, from blue to yellow in turquoise. The results show that the determination coefficient (R2) in the b*–Cu–Fe model is 0.886 with w(ZnO), w(V2O5) and w(Cr2O3) as excluded variables, indicating that copper and iron contents have good correlation with b* (table 2). The significance coefficient is lower than 0.001, indicating a good linear regression. Thus, Cu and Fe content mainly contributes to the hue variation from blue to yellow in turquoise.

Table 2.

Model of b*–Zn–Fe stepwise regression.

| model | factors | unstandardized | standardized | T | sig | R2 | adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | constant | 29.094 | — | 9.999 | 0.000 | 0.857 | 0.853 |

| CuO (%) | −2.477 | −0.926 | −14.064 | 0.000 | |||

| 2 | constant | 24.126 | — | 7.615 | 0.000 | 0.886 | 0.879 |

| CuO (%) | −2.310 | −0.863 | −13.565 | 0.000 | |||

| Fe2O3 (%) | 0.777 | 0.181 | 2.839 | 0.008 |

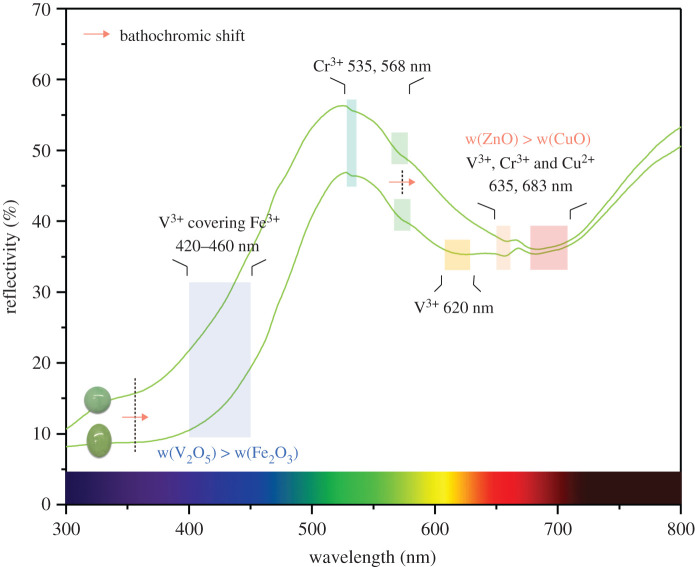

3.3. FTIR

The infrared spectra in 2000–400 cm−1 range possess prominent absorption bands arising from the vibrations of the OH, H2O and (PO4)3− units (table 3). The P–O stretching vibrations of the phosphate units (PO4)3− are located at 1200–900 cm−1, while the coupled motions of the tetrahedral and octahedral frameworks are situated below 700 cm−1 [8]. The O–H bending vibrations of the OH units are located at 833 and 781 cm−1, while that of the H2O molecules are located near 1637 cm−1 [30,31]. Since the M–H2O has weak hydrogen bonds, the infrared spectra of turquoise shows weak absorption when the wavenumber is over 1200 cm−1 [32]. The C–O stretching vibrations of the carbonate group (CO3)2− are located near 1450 cm−1, with weak absorption, which can possibly be attributed to the presence of the admixed carbonate on the chalcosiderite-faustite surface [54]. Different metal cations can cause changes in frequency and absorption strength.

Table 3.

Infrared peaks of turquoise samples.

| turquoise |

chalcosiderite |

faustite |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B11 | B16 | G01 | G12 | G09 | G14 | |

| H–O–H bending vibration |

1637 | 1637 | — | — | — | — |

| C–O stretching vibration |

— | — | 1448 | 1448 | 1450 | 1450 |

| P–O stretching vibration |

1199 | 1196 | — | — | — | — |

| 1121 | 1123 | 1118 | 1117 | 1119 | 1121 | |

| 1059 | 1059 | 1051 | 1057 | 1061/1043 | 1061/1043 | |

| 1007 | 1007 | 1009 | 1009 | 1005 | 1003 | |

| O–H bending vibration |

833 | 833 | 833 | 833 | 831 | 798 |

| 781 | 781 | 781 | 781 | 796 | ||

| P–O stretching vibration |

650 | 650 | 646 | — | 648 | 646 |

| 608 | 608 | — | — | 623 | 623 | |

| 571 | 569 | 565 | 567 | 588 | 590 | |

| 536 | 534 | — | 536 | 536 | 553 | |

| 484 | 480 | 478 | 480 | 480 | 480 | |

| 449 | 451 | 449 | 451 | 453 | 453 | |

Cu-rich turquoise clearly has a lower reflectivity than Fe-rich chalcosiderite and Zn-rich faustite, especially in the spectral region caused by the phosphate group (PO4)3− (figure 6a). PO4 tetrahedra in the crystal structure of turquoise shares O2− corners with MO6 octahedra, and small-sized trivalent cations (Al3+) form strong bonds with O2− ions, resulting in a weak polarity in the phosphate groups (PO4)3− in blue turquoise. Substitutions of Al by medium-sized trivalent cations (Fe3+, V3+ and Cr3+) change the lattice environment of chalcosiderite and faustite, where the bond energy of Fe–O is lower than that of Al–O, enhancing the polarity of the phosphate group (PO4)3− and leading to high reflectivity in the infrared spectra. Increasing Fe content reduces the peak resolution of P–O stretching vibration below 700 cm−1, and chalcosiderite loses absorption peaks at 609 and 648 cm−1, distinguishing from turquoise. The absorption peak at 1057 cm−1 in turquoise is separated into two peaks at 1061 and 1047 cm−1 in faustite.

Figure 6.

(a) FTIR spectra of turquoise, chalcosiderite and faustite. (b) Correlation between ROH and Cu content. The ROH data presents in three-group distributions on the diagram, based on K-means clustering analysis and Fisher discriminant analysis; turquoise is shown in blue, chalcosiderite is shown in green and faustite is shown in green-yellow. FTIR spectra of them in the 700–900 cm−1 region reflect changes in frequency and absorption strength.

Previous studies have suggested that the OH bending variation of the OH units can be used to determine the origin of turquoise [30–32], and its absorption peaks have been used to identify differences in the chemical composition of turquoise. Therefore, we focused on OH bending variation and carried out K-means clustering analysis and Fisher discriminant analysis to divide all turquoise samples into different groups based on their chemical composition.

K-means clustering analysis allows the quick division of research objects into relatively homogeneous groups [55–57]. Fisher discriminant analysis, one of the most important multivariate statistical analysis methods, can summarize the common feature from various groups to obtain discriminant formulae, identifying the accuracy of clustering analysis [58]. The clustering significance (sig) is lower than 0.001 with a cluster number of 3, as w(CuO), w(Fe2O3) and w(ZnO) are independent variables. All sigs in the Fisher discriminant analysis are lower than 0.001, indicating that discriminant variables can work well in the classification. The discriminant formulae are shown in table 4 with an accuracy as high as 100.00%, suggesting that the model is reliable for the classification results of the chemical composition in turquoise. Thus, all samples are classified into three categories, matching three end-members in the turquoise group, including turquoise (21 pieces), chalcosiderite (12 pieces) and faustite (two pieces).

Table 4.

Fisher discriminant accuracy.

| (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | numbers | the discriminant formulae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21 | |

| 2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 2 | |

| 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 12 |

The ROH representing the reflectivity ratio of the double peaks at 781 and 833 cm−1 is negatively correlated with Cu content and is used to identify the three turquoise categories (figure 6b). Chalcosiderite has a higher resolution and absorption reflectivity than turquoise and faustite in the 700–900 cm−1 range, and its ROH ranges from 0.765 to 0.885, with an average value of 0.802. The ROH of faustite is over 1.000, which allows faustite to be distinguished from other subspecies in the turquoise group. However, greenish yellow faustite is high in V and shows a single peak at 798 cm−1, with w(V2O5) > 1.00%, lacking the double peaks from OH bending vibration.

3.4. Water immersion experiment

Adsorbed water content is one of the most important factors that influence turquoise colour, and one which influences turquoise texture and crystallinity. A water immersion experiment was designed in this paper. Thirty-five samples of turquoise were measured using the portable spectrophotometer to obtain control colour data before the experiment. They were then immersed in clean water under atmospheric temperature and pressure conditions for 24 h. They were removed from the water, wiped away free water on the surface and were quickly measured again to obtain final colour data. Specific gravity (SG) testing and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) experiment were carried out on the samples before water immersion experiment to better elucidate structural and textural characteristics of turquoise with different SGs.

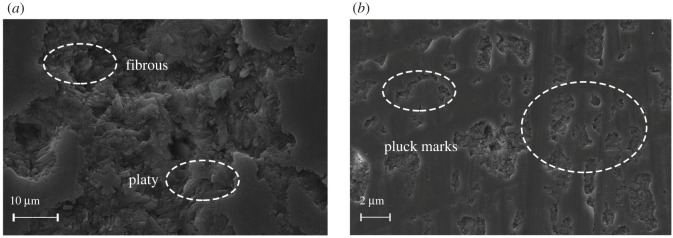

3.4.1. Micro-observation analysis

The SG of turquoise was measured using a hydrostatic weighing scale with an accuracy of 0.001 g, and samples were put in water for less than 2 s. The SG of turquoise ranges from 2.59 to 2.87 based on the Archimedes principle. Two samples (B05 and B06) with different SGs (2.72 and 2.66) were selected for SEM analysis. Scanning electron microscopy was used to examine the micro-structure and morphology of turquoise surface, especially with respect to its structural compactness and porosity [8,59,60].

Detailed petrography of the SEM images shows distinct differences between loose and dense turquoise. The turquoise (B05) with a high SG has a relatively homogeneous texture and blocky morphology, with a few pluck marks as voids due to polishing (figure 7). However, the turquoise (B06) with a low SG shows a porous texture, consisting of fibrous and platy crystallites, and it has more pluck marks than the sample B06 (figure 8).

Figure 7.

SEM images of moderate-dense turquoise (sample B05, SG = 2.72) (a) with a crystalline blocky morphology and (b) a few pluck marks caused by polishing.

Figure 8.

SEM images of low-dense turquoise (sample B06, SG = 2.66) (a) with a fibrous and platy morphology and (b) more pluck marks than the sample B05.

3.4.2. Colour variation analysis

Previous research using differential thermal thermogravimetric analysis confirms that the absorbed water content, easily escaping from turquoise pores or textural fractures, is less than 2% and most of the turquoise cannot be water-saturated without human intervention. According to naked-eye observations during water immersion experiment, all samples displayed significant colour variation in the first 1 min, which then became steady with no further naked-eye colour change after 5 min; turquoise colour changed intensive after the experiment, which was more obvious in blue turquoise compared with samples of different colours. A weaker colour difference was found in denser turquoise samples. The intense colour change occurred in loose turquoise samples that had air bubbles on their surface.

Based on the CIE 1976 L*a*b* colour system, the control colour data of all turquoise samples before water immersion experiment is noted: lightness L* ∈ (55.86, 85.26), chroma C* ∈ (20.07, 32.95) and hue angle ho ∈ (116.47, 231.86). An empirical expression shows that hue angle of turquoise has extremely negative correlation with colorimetric coordinate b* (x) (figure 9)

| 3.3 |

The R2 value is 0.996, indicating that b* can explain the variation in hue angle for most turquoise.

Figure 9.

Relationship between colorimetric coordinate b* and hue angle h° or chroma C* in turquoise’s colour. The colour plots of turquoise distribute in the uniform colour space CIE 1976 L*a*b* on the top right. Note: a* ∈ (−29.06, −9.26), b* ∈ (−25.27, 26.80) and L* ∈ (55.86, 88.31).

The chromatic diagram (a two-dimensional plane composed of coordinates a* and b*) shows that the a*–b* range of blue turquoise becomes narrower after water immersion experiment and shifts to the negative direction of coordinate axis b*, indicating that increasing absorbed-water content enhances blue hue and makes colour more brilliant. However, the a*–b* range of blue-green turquoise slightly shifts to the positive direction of the coordinate axis a*, indicating that increasing absorbed-water content enhances green hue. For yellow-green turquoise, the a*–b* range becomes narrower in the direction of coordinate axis a*, indicating that the yellow-green turquoises show low colour resolution between individuals after water immersion experiment (figure 10a).

Figure 10.

(a) CIE 1976 L*a*b* chromatic diagram of turquoise colours before and after water immersion experiment. (b) Box chart of lightness difference (ΔL*), chroma difference (ΔC*) and hue angle difference (Δho) in turquoise (classified in six hue groups).

Based on the six hue groups mentioned above, further quantitative analysis was carried out to investigate the impact increased absorbed-water content had on the lightness difference (ΔL*), chroma difference (ΔC*) and hue angle difference (Δho) (figure 10b). The results show that an increase in absorbed-water content results in a decrease in lightness of colour for all turquoise samples (ΔL* < 0); this indicates that absorbed water has a negative effect on the turquoise lightness. The negative effect of adsorbed water on greenish yellow turquoise is the most significant with |ΔL*|maximum as high as 14.39. The blue turquoise displays intense colour and enhances chroma with increasing absorbed-water content; this indicates that absorbed water has a positive impact on the chroma (ΔC* > 0, |ΔC*|max = 9.52), while yellow-green turquoise appears deeper in colour with decreasing in chroma. However, blue-green turquoise shows extremely low chroma differences, which is difficult to attribute to changes in absorbed-water content or instrument error. The hue angle of blue and yellow-green turquoises is positively affected by absorbed water (Δho > 0) while that of blue-green turquoise is negatively affected.

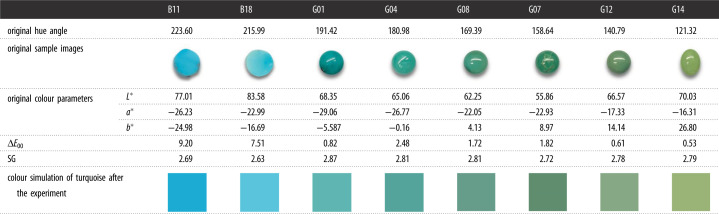

3.4.3. Colour difference analysis

Colour difference is a comprehensive description of differences between a control colour and a sample colour, involving lightness differences, chroma differences and hue angle differences. The CIE DE2000 colour difference (ΔE00) is well correlated with the visual judgement, and we can easily distinguish the difference between two kinds of colours with a large ΔE00. The colour difference (ΔE00) is calculated using the CIE DE2000 formula (table 5), indicating that the colour of blue turquoise varies greatly with increasing absorbed-water content; this variation is easily perceived by naked-eye observation due to a large ΔE00 of 9.20. The SGs of all samples are divided into three grades in accordance with the Turquoise Grading of the Chinese National Standard [61]. Specifically, SG > 2.70 indicates an extremely dense texture, 2.50 < SG ≤ 2.70, a dense texture and SG ≤ 2.50, a loose texture. Therefore, all turquoise samples in this paper were divided into four degrees; e.g. high-dense (SG > 2.80), moderate-dense (2.70 < SG ≤ 2.80), low-dense (2.60 < SG ≤ 2.70) and slight-loose (2.50 < SG ≤ 2.60).

Table 5.

The colour difference (ΔE00) of turquoise based on water immersion experiment.

|

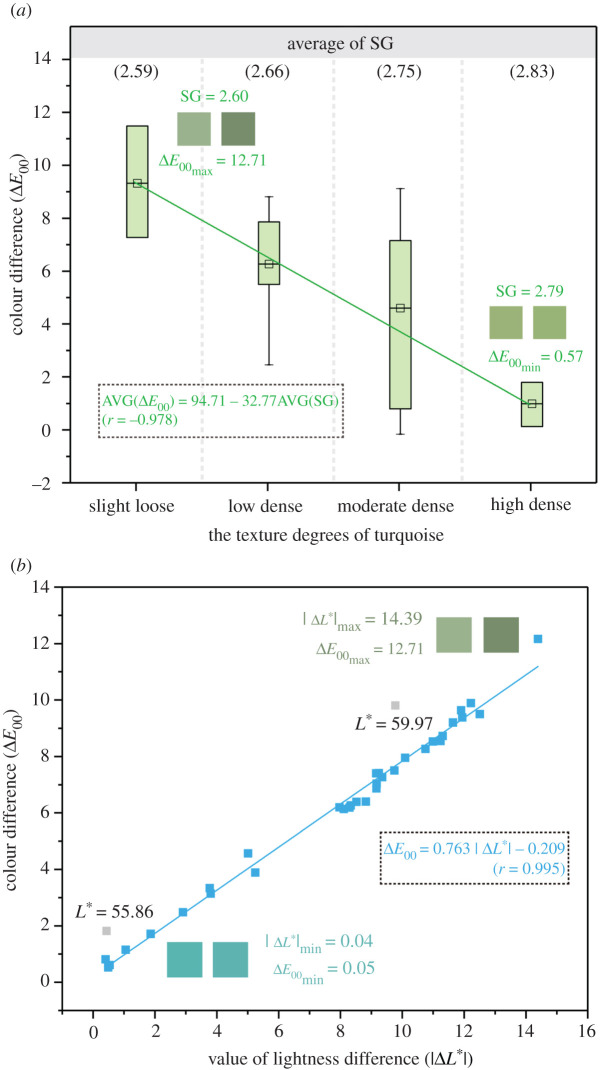

The box chart in figure 11a indicates that moderate- and low-dense turquoises exhibit great variation in colour difference with a large range; this may be attributed to the uneven absorbed-water content in the original turquoise. The average SG is negatively correlated with the average ΔE00 in each degree, which can be expressed as (figure 11a)

| 3.4 |

The result indicates that water-filled pores are well developed in slight-loose turquoise with a low SG, giving rise to obvious colour variation with increasing absorbed-water content. Meanwhile, the colour difference (ΔE00) follows a positive trend with the value of lightness difference (|ΔL*|) for all turquoise samples (figure 11b)

| 3.5 |

Figure 11.

(a) Box chart of colour difference (ΔE00) with four texture degrees; the AVG of ΔE00 for each texture degree is negatively correlated with the AVG of SG. (b) The correlation between the value of lightness difference |ΔL*| and colour difference ΔE00, where the discrete grey points are due to a lower lightness (L* < 60).

The r value is high at 0.995, indicating that lightness difference can exert a significant impact on colour difference caused by water immersion experiment. The lightness of the two samples, deviating from the fitting line (shown as grey points in figure 11b), displays a weaker influence on colour difference due to their darker lightness (L* < 60). In summary, loose turquoise with a lower SG tends to possess a greater colour difference with a significant decrease in lightness. For blue turquoise, an increasing amount of absorbed water results in a decrease in lightness (with less white) and an increase in chroma (a deeper blue). Since high lightness has an adverse impact on colour blue and results in a low-level quality of turquoise's blue, the result also means that increasing absorbed-water content can enhance colour blue quality of turquoise, which helps it to show fancy and brilliant blue.

4. Conclusion

In order to establish a suitable evaluation system in the future research, with an emphasis on colour quality of turquoise, it is necessary to better understand the causes of colour transition in turquoise. This study puts forward an effective and non-destructive method to quantitatively analyse the colour of turquoise, and combines with chemical and spectral analyses, determining the impact of trace metal cations and absorbed water on colour of turquoise. Our conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Fe content correlates well with Al content in green-hue turquoise (R2 = 0.980), indicating that substitution of Al by Fe3+ results in the solid-solution series of turquoise-chalcosiderite. With increasing Fe content, the double absorption peaks at 422 and 428 nm merge into a strong narrow band at 426 nm in UV–Vis spectra. The band at 426 nm shifts into 428 nm with increasing V content, corresponding to a colour transition from blue to green in turquoise. Zn2+ suppresses the blue in turquoise, V3+ enhances absorption in the violet, blue and orange regions of the spectra, and Cr3+ enhances absorption in the red and green regions of the spectra, all of which result in the vivid greenish yellow of faustite.

-

(2)

Substitutions of Al by medium-sized trivalent cations (primarily Fe3+ and V3+) enhance the polarity of the phosphate group (PO4)3−, increasing absorption strength in the infrared spectra for analogues of turquoise. FTIR spectra provide a highly efficient way to distinguish faustite (ROH > 1.000) from the turquoise group using the reflectivity ratio (ROH) of the double absorption peaks at 781 and 833 cm−1.

-

(3)

Increasing absorbed-water content has a negative impact on the lightness of all turquoise samples, whereas, it enhances chroma for blue turquoise. Loose turquoise with a low SG tends to possess a large colour difference, especially showing a significant decrease in lightness. Increasing absorbed-water content can enhance colour blue quality of turquoise, which helps it to show fancy and brilliant blue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the patient guideline and rigorous suggestions from Y. Guo and support from the Lab of Gemological Research at School of Gemmology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing. We also gratefully acknowledge for valuable reference on the crystal structure of turquoise from A. Y. Abdu.

Ethics

This article does not present research with ethical considerations.

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.qjq2bvqd5) [62].

Authors' contributions

X.W. totally conceived and designed the study, carried out experiments, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. Y.G. provided valuable suggestions throughout, critically revised the manuscript and supported on samples. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

There is no funding to report for the submission.

References

- 1.Ye XH, Ren J, Xu H, Chen GL, Zhao HT. 2014. A preliminary study on geological provenance of turquoise artifacts from Erlitou site. Quat. Sci. 34, 212-223. ( 10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2014.01.25) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thibodeau AM, Luján LL, Killick DJ, Berdan FF, Ruiz J. 2018. Was Aztec and Mixtec turquoise mined in the American Southwest? Sci. Adv. 4, eaas9370. ( 10.1126/sciadv.aas9370) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thibodeau AM, Killick DJ, Hedquist SL, Chesley JT, Ruiz J. 2015. Isotopic evidence for the provenance of turquoise in the southwestern United States. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 127, 1617-1631. ( 10.1130/B31135.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tallet P, Marouard G. 2014. The harbor of Khufu on the red sea coast at Wadi al-Jarf, Egypt. Near East. Archaeol. 77, 4-14. ( 10.5615/neareastarch.77.1.0004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandomani EM, Rashidnejad-Omran N. 2020. Electron microprobo study of turquoise-group solid solutions in the Neyshabour and Meydook mines, northeast and southern Iran. Can. Mineral. 58, 71-83. ( 10.3749/canmin.1900004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen QL, Yin ZW, Qi LJ, Xiong Y. 2012. Turquoise from Zhushan county, Hubei province, China. Gems Gemol. 48, 198-204. ( 10.5741/GEMS.48.3.198) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolitsch U, Giuseppetti G. 2000. The crystal structure of faustite and its copper analogue turquoise. Mineral. Mag. 64, 905-913. ( 10.1180/002646100549733) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdu YA, Hull SK, Fayek M, Hawthorne FC. 2011. The turquoise-chalcosiderite Cu(Al,Fe3+)6(PO4)4(OH)8̀4H2O solid-solution series: a Mössbauer spectroscopy, XRD, EMPA, and FTIR study. Am. Mineral. 96, 1433-1442. ( 10.2138/am.2011.3658) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foord EE, Taggart JE. 1998. A reexamination of the turquoise group: the mineral aheylite, planerite (redefined), turquoise and coeruleolactite. Mineral. Mag. 62, 93-111. ( 10.1180/002646198547495) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Q, Xu Z. 2014. Progress in the study of color emerging mechanism of turquoise. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 33, 136-140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang HF, Lin CY, Ma ZW, Yang ZG, Zhang EL. 1982. Magnetic properties, characteristic spectra and color of turquoise. Acta Mineralogica Sin. 4, 254-261. ( 10.1007/BF03179305) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue HQ, Chen PR, Li QH. 1985. Electron para-magnetic resonance and electron micro-probe studies on iron-containing turquoise. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 13, 1994-2020. ( 10.14062/j.issn.0454-5648.1985.02.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang H, Ren L. 2019. Unique vanadium-rich emerald from Malipo, China. Gems Gemol. 55, 338-352. ( 10.5741/GEMS.55.3.338) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Qi LJ, Zhang Q, Jiang XP. 2014. The gemological and mineral characteristics of variscite from Ma’anshan of Anhui province. Rock Miner. Anal. 33, 690-697. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei JC, Huang WZ, Zhang Q, Zhai SH. 2019. Chemical constituents and spectra characterization of demantoid from Russia. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 39, 3849-3854. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2019)12.3849.06) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Yang MX, Di and JR, He C. 2018. Spectra characterization of the uvarovite in anorthitic jade. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 38, 1758-1762. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2018)06.1758.05) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy B, Frost R, Weier M, Martens W. 2006. Ultraviolet-visible, near infrared and mid infrared reflectance spectroscopy of turquoise. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 14, 241. ( 10.1255/jnirs.641) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull S, Faye M, Mathien FJ, Shelley P, Durand KR. 2018. A new approach to determining the geological provenance of turquoise artifacts using hydrogen and copper stable isotopes. J. Archaeol. Sci. 35, 1355-1369. ( 10.1016/j.jas.2007.10.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heng YX, Li YX, Tan YC, Wang WL, Yang ZH, Cui JF. 2016. Application of LA-ICP-AES to distinguish the different turquoise mines. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 36, 3313-3319. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2016)10-3313-07) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crespoe-Feo E, Garcia-Guinea G, Correcher V, Prado P. 2010. Luminescence behaviors of turquoise [CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O]. Radiat. Meas. 45, 749-752. ( 10.1016/j.radmeas.2009.12.027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chassapis L, Roulia M. 2008. Evaluation of low-rank coals as raw material for Fe and Ca organo mineral fertilizer using a new EDXRF method. Int. J. Coal Geol. 75, 185-188. ( 10.1016/j.coal.2008.04.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nageeb Rashed M, Eltaher MA, Abdou AN. 2017. Absorption and photocatalysis for methyl orange and Cd removal from wastewater using TiO2/sewage sludge-based activated carbon nanocomposites. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 170834. ( 10.1098/rsos.170834) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes SJ, Picard CP. 1993. The behaviour of platinum-group elements during partial melting, crystal fractionation, and sulphide segregation: an example from the Cape Smith Fold Belt, northern Quebec. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 79-87. ( 10.1016/0016-7037(93)90470-H) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gan TT, Zhao NJ, Yin GF, Chen M, Wang X, Hua H. 2020. Preconcentration with Chlorella vulgaris combined with energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for rapid determination of Cd in water. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 200182. ( 10.1098/rsos.200182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritsch E, McClure SF, Ostrooumov M, Andres Y, Moses T, Koivula JI, Kammerling RC. 1999. The identification of Zachery-treated turquoise. Gems Gemol. 35, 4-16. ( 10.5741/GEMS.35.1.4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabbaghi H. 2018. A combinative technique to recognise and discriminate turquoise stone. Vib. Spectrosc. 99, 93-99. ( 10.1016/j.vibspec.2018.09.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhary G. 2010. A new type of composite turquoise. Gems Gemol. 46, 106-113. ( 10.5741/GEMS.46.2.106) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Yang MX, Lu R, Shen XT, He C. 2018. Study on EDXRF method of turquoise composition. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 38, 1910-1916. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2018)06-1910-07) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan J, Liu XB, Wang JA, Fang B, Liu PJ, Yang BB. 2015. Determination of mineral compositions of new imitated turquoise by FTIR-XRD-XRF. Rock Miner. Anal. 34, 544-549. ( 10.15898/j.cnki.11-2131/td.2015.05.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen WJ, Shi GH, Wang Y, Ren J, Yuan Y, Dei H. 2018. Infrared and Roman spectra of high-quality from Hubei and Anhui, China: characteristics and significance. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 38, 1059-1065. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2018)04.1059.07) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren J, Ye XH, Wang Y, Luo SQ, Shi GH. 2015. Source constraints on turquoise of the Erlitou site by the infrared spectrum. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 35, 1767-1772. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2015)10.2767.06) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang QN, Di JR, He B. 2018. Mineralogical and spectral characteristics of faustite from Sonora, Mexico. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 39, 2059-2066. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2019)07.2059.08) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen QL, Wang HT, Liu XY, Qin C, Bao DQ. 2020. Study on gemology characteristics of the turquoise from Mongolia. Spectrosc. Spectra Anal. 40, 2164-2169. ( 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2020)07-2164-06) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frost RL, Reddy BJ, Martens WN, Weier M. 2006. The molecular structure of the phosphate mineral turquoise—a Raman spectroscopic sudy. J. Molecular Struct. 788, 224-231. ( 10.1016/j.Molstruc.2005.12.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pointer MR. 1981. A comparison of the CIE 1976 colour spaces. Color Res. Appl. 6, 108-118. ( 10.1002/col.5080060212) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirillova NP, Vodyanitskii YN, Sileva TM. 2014. Conversion of soil color parameters from the Munsell system to the CIE L*a*b* system. Genes. GeoGr. Soils 48, 468-475. ( 10.1134/S1064229315050026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vodyanitskii YN, Kirillova NP. 2016. Application of the CIE L*a*b* system to characterize soil color. Soil Phys. 49, 1259-1268. ( 10.1134/S1064229316110107) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madhura MP, Swati B. 2020. Characterization and optimization of color attributes chroma (C*) and lightness (L*) in offset lithography halftone print on packaging boards. Color Res. Appl. 45, 325-335. ( 10.1002/col.22456) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan SS, Luo MR. 1999. A colour-difference formula for assessing large colour differences. Color Res. Appl. 24, 344-355. () [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu HS, Yaguchi H, Shioiri S. 2001. Estimation of color-difference formulae at color discrimination threshold using CRT-generated stimuli. Opt. Rev. 8, 142-147. ( 10.1007/s10043-001-0142-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo Y, Wang H, Li X, Dong SR. 2016. Metamerism appreciation of jadeite-jade green under the standard light sources D65, A and CWF. Acta Geol. Sin. 90, 2097-2103. ( 10.1111/1755-6724.13024) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo Y, Zong X, Qi M. 2018. Feasibility on quality evaluation of jadeite-jade color green based on GemDialogue color chip. Multimed. Tools Appl. 67, 1-16. ( 10.1007/s11042-018-5753-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan X, Guo Y, Zi YL. 2019. Impact of different standard lighting sources on red jadeite and color quality grading. Earth Sci. Res. 23, 371-378. ( 10.15446/esrj.v23n4.84113) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang J, Guo Y. 2019. Color effect of light sources on peridot based on CIE1976 L*a*b* color system and round RGB diagram system. Color Res. Appl. 44, 1-9. ( 10.1002/col.22419) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang J, Guo Y, Xu C. 2019. Metameric effects on peridot by changing background color. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 36, 2030-2039. ( 10.1364/JOSAA.36.002030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang YL, Guo Y, Tan YT, Chen ZS. 2016. The influence of difference standard illuminants on tourmaline color red. Acta Mineralogica Sin. 36, 220-224. ( 10.1117/12.870663) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen RP, Guo Y. 2020. Study on the effect of heat treatment on amethyst color and the cause of coloration. Sci. Rep. 10, 14927. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-71786-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu FK, Guo Y, Lv SJ, Chen GG. 2020. Application of the entropy method and color difference formula to the evaluation of round brilliant cut diamond scintillation. Mathematics 8, 1489. ( 10.3390/math8091489) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLaren K. 2008. The development of the CIE 1976 (L*a*b*) uniform colour-space and colour-difference formula. Color. Technol. 92, 338-341. ( 10.1111/j.1478-4408.1976.tb03301.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gómez-Polo C, Muñoz MP, Luengo MCL, Vicente P, Galindo P, Casado MM. 2016. Comparison of the CIELab and CIEDE2000 color difference formulas. J. Prosthet. Dent. 115, 65-70. ( 10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pecho OE, Ghinea R, Alessandretti R, Pérez MM, Bona AD. 2016. Visual and instrumental shade matching using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulas. Dent. Mater. 32, 82-92. ( 10.1016/j.dental.2015.10.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin Y, Liu Z, Wang PF. 2013. Research on contrast sensitivity function of hue in CIE 1976 L*a*b* color space. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. 33, 824-827. ( 10.3969/j.issn.1001-0645.2013.08.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Höskuldsson A. 2011. Variable and subset selection in PLS regression. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 55, 23-38. ( 10.1016/S0169-7439(00)00113-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harner PL, Gilmore MS. 2014. Visible-near infrared spectra of hydrous carbonates, with implications for the detection of carbonates in hyperspectral data of Mars. Icarus 250, 204-214. ( 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.037) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo Y, Zhang XY, Li X, Zhang Y. 2018. Quantitative characterization appreciation of golden citrine by the irradiation of [FeO4]4−. Arab. J Chem. 11, 918-923. ( 10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.02.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo Y, Wang H, Du HM. 2016. The foundation of a color-chip evaluation system of jadeite-jade green with color difference control of medical device. Multimedia Tools Appl. 75, 14 491-14 502. ( 10.1007/s11042-016-3291-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fonteles HRN, Veríssimo CUV, Pereira HG, Barbosa IG. 2020. Hybrid multivariate typological model for the banded iron formations from the Bonito mine, Northeastern Brazil. Appl. Geochem. 123, 104779. ( 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2020.104779) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang ZQ, Ye M, Shen AH. 2019. Characterisation of peridot from China's Jilin province and from North Korea. J. Gemmol. 36, 436-446. ( 10.15506/JoG.2019.36.5.436) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo ZM, Shen XT, Zhu QW, Liu L. 2016. How structure compactness impacts the quantitative colour research of turquoise. J. Gems Gemmol. 18, 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alessia C, et al. 2017. Micro-Raman spectroscopy and complementary techniques (hXRF,VP-SE-EDS, μ-FTIR and Py-GC/MS) applied to the study of beads from the Kongo Kingdom (Democratic Republic of Congo). J. Raman Spectrosc. 48, 1468-1478. ( 10.1002/jrs.5106) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. China National Bureau of Technical Supervision. 2009 GB/T 36169-2018. Turquoise Grading[P], Chinese National Standards. Beijing, People's Republic of China: Standards Press of China.

- 62.Wang X, Guo Y. 2016. Data from: The impact of trace metal cations and absorbed water on colour transition of turquoise. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.qjq2bvqd5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wang X, Guo Y. 2016. Data from: The impact of trace metal cations and absorbed water on colour transition of turquoise. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.qjq2bvqd5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.qjq2bvqd5) [62].