Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this paper is to review and discuss historical concepts about the celebration of Chiropractic Day.

Discussion

Daniel David Palmer attributed September 18, 1895 to be the day that he delivered the first chiropractic adjustment. As the chiropractic profession grew, the celebration of Chiropractic Day became more widespread throughout the United States and the world. This paper offers suggestions about how to celebrate Chiropractic Day. Activities include educating, learning, honoring, volunteering, and engaging.

Conclusion

The chiropractic profession celebrates its birth on September 18. Regardless of the many different names used over the past 125 years, including Chiropractic Founder's Day, Chiropractic Rally Day, Chiropractic Anniversary, and Chiropractic Discovery Day, the celebration of this special day provides an opportunity to reflect on how far the profession has come and how chiropractors continue to help and serve their patients.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, History, Health Occupations

Introduction

Few health professions can state the specific date they began. As to their declared founders, orthodox Medicine often claims Hippocrates, Nursing claims Florence Nightingale, and Osteopathy claims Andrew Taylor Still.1, 2, 3 Chiropractic's founder is Daniel David Palmer. This profession is unique in that it claims not only to have the specific date, but also the name of one of the earliest, if not the first, patient. The purpose of this paper is to review the historical background and origins of Chiropractic Day, which is celebrated annually on September 18 as the birth of the chiropractic profession.

Discussion

Chiropractic in the Early Years

When reviewing these events, it is important to interpret these circumstances considering the era in which people practiced and within the context of the social and cultural norms of those times. We also need to recall that medical interventions that we take for granted today, had not yet been established in the late 1800s when chiropractic began. For example, aspirin was not available until 1899.4 Though penicillin was discovered in 1928, its first clinical trial was not until 1941.5,6 And, the first randomized controlled trial in orthodox medicine did not occur until 1948.7

In the 1880s, the American Medical Association, which represented organized, regular medicine, was beginning to establish its cultural dominance within American healthcare.8 The Iowa Medical Society was strongly influencing state legislature and gaining more control over what types of healers were allowed to practice healthcare. In 1886, a law developed by Iowan regular medical doctors was passed that made it illegal to practice healthcare for any healer that was not a regular physician in their state. Thus, it was a challenging time for anyone who wished to practice healthcare outside of the regular medical profession.

Chiropractic originated in Davenport, Iowa, in the mind and at the hands of Daniel David Palmer. Many years before he declared the founding of chiropractic, he practiced as a magnetic healer without machines, gadgets, drugs, or surgery. Palmer practiced using natural methods, when regular medical doctors were still using heroic methods (ie, purging and puking), which had substantial morbidity and mortality risks for patients.9,10 Although some might try to demonize the magnetic practices of D.D. Palmer, his healing methods seem far safer compared to the heroic procedures offered by regular medicine at that time. So in following the Hippocratic oath, which was to first do no harm to patients (ie, primum non nocere),11 D.D. Palmer was both an advocate and practitioner. Thus, one could say that chiropractic was a reasonable choice for Americans who were searching for safe treatments for their ills.

He was an avid reader and continued to learn throughout his lifetime.12, 13, 14 This may have been because he was a schoolteacher earlier in his career and was trained to question and encourage others to be lifelong learners.15 He continued to develop ideas and propose new hypotheses even after he founded chiropractic.16,17 Thus, due to his inquisitive and creative nature, it is not surprising that his healing methods evolved starting when he began practicing as a magnetic healer and throughout his discovery and development of chiropractic.

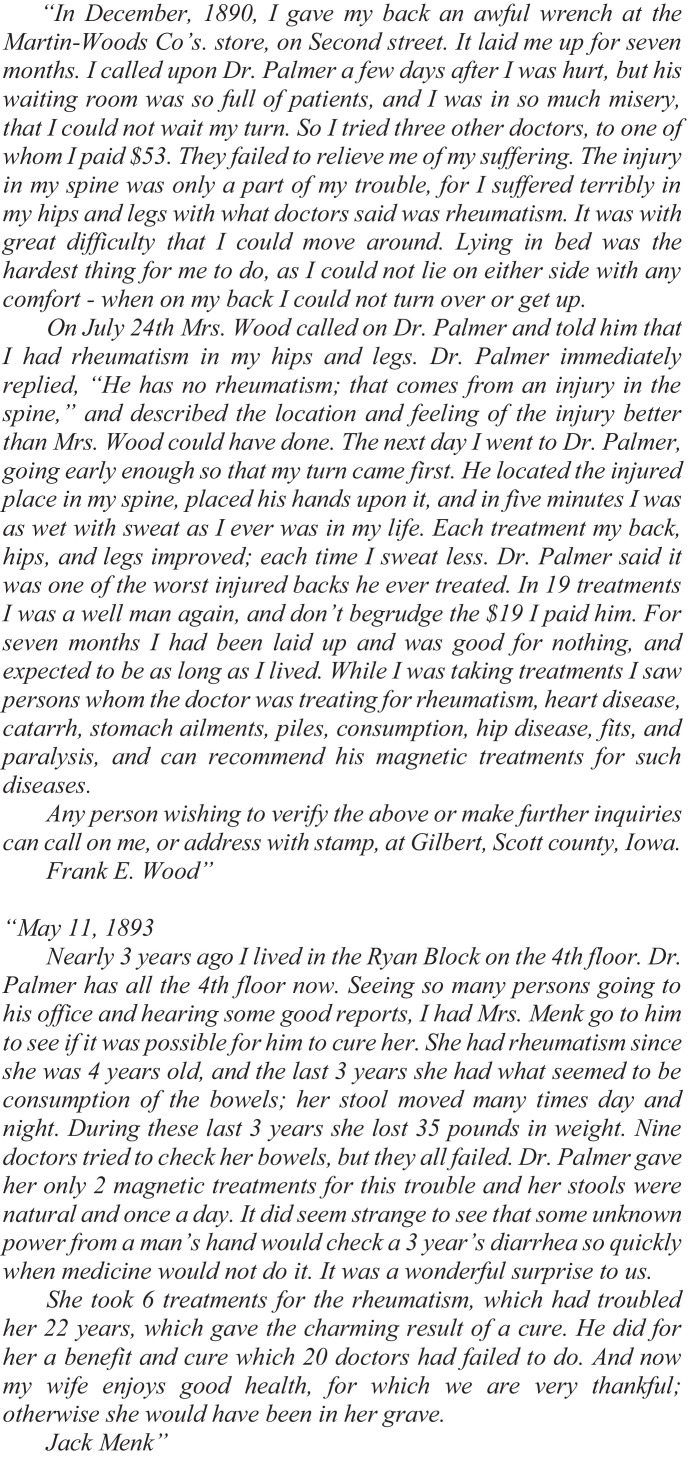

During the first 10 years, Palmer's magnetic practice thrived. Patients wrote letters describing their results from Palmer's treatments.18 (Figure 1) However, there was a turning point in which his approach changed. Harvey Lillard was a patient that stood out in his mind. It seems that the association between Lillard's complaint and the treatment that Palmer delivered resulted in Palmer's revelation. He described the event in the 1904 volume 1 number 1 edition of The Chiropractor.19

"For nine years previous to the naming of Chiropractic, Dr. D.D. Palmer was practicing the healing art under the head of magnetic, but not as others, who slapped and rubbed. He aimed to locate in the patient THE CAUSE of each disease. … On September 18, 1895, Harvey Lillard called upon Dr. Palmer. The doctor asked him how long he had been deaf. He answered "Seventeen years." He was so deaf that he could not hear the rumbling of a wagon on the street. Mr. Lillard informed the doctor that at the time he became deaf he was in a cramped position and felt something give in his neck. Upon examination there was found a displaced vertebra, a spine that was not in line. Dr. Palmer informed Mr. Lillard that he thought he could be cured of his deafness by fixing his back. He consented to have it fixed; we now say adjusted. Two adjustments were given Harvey Lillard in the dorsal vertebra, which replaced a displaced vertebra, freeing nerves that had been paralyzed by pressure... Mr. Lillard can hear today as well as other men. He resides at 1031 Scott Street, Davenport, Iowa."19

Fig 1.

Two examples of patients’ letters to D.D. Palmer, published in his 1896 newsletter that were dated prior to the beginning of the chiropractic profession. 18

During this period of discovery and development, Palmer began using the spinous process as a lever to adjust the vertebral column “back into alignment.”20 He continued to improve his techniques and questioned the fundamentals of health as to why some people became sick and others were well under the same conditions. In his own words from his 1910 text, D.D. Palmer recounted the events leading up to the first chiropractic adjustment.

“One question was always uppermost in my mind in my search for the cause of disease. I desired to know why one person was ailing and his associate, eating at the same table working in the same shop, at the same bench, was not. Why? What difference was there in the two persons that caused one to have pneumonia, catarrh, typhoid or rheumatism, while his partner, similarly situated, escaped? Why? This question had worried thousands for centuries and was answered in September, 1895.

Harvey Lillard, a janitor, in the Ryan Block, where I had my office, had been so deaf for 17 years that he could not hear the racket of a wagon on the street or the ticking of a watch. I made inquiry as to the cause of his deafness and was informed that when he was exerting himself in a cramped, stooping position, he felt something give way in his back and immediately became deaf. An examination showed a vertebra racked from its normal position. I reasoned that if that vertebra was replaced, the man's hearing should be restored. With this object in view, a half-hour's talk persuaded Mr. Lillard to allow me to replace it. I racked it into position by using the spinous process as a lever and soon the man could hear as before.”20

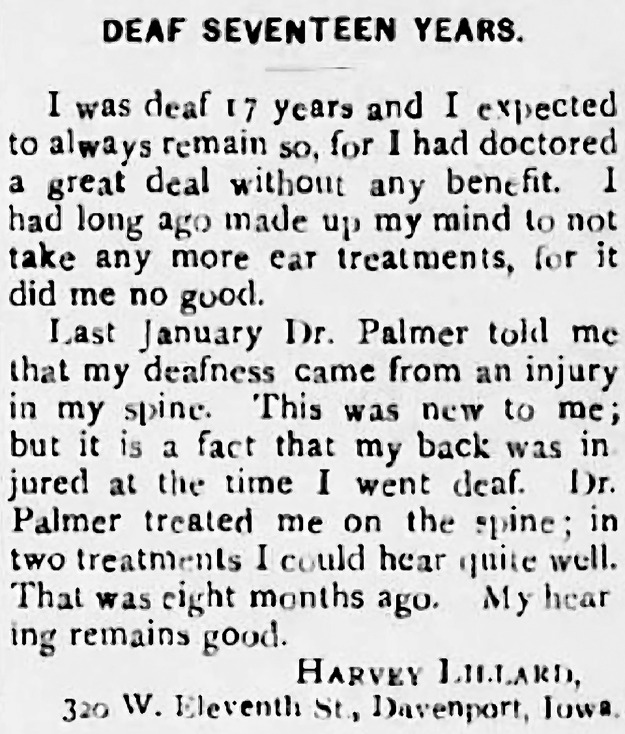

Several years later, when pressed to report a day for the first chiropractic adjustment, D.D. Palmer said that Harvey Lillard's first treatment was on September 18. Although, the record shows that the exact date has been questioned and Lillard's treatment may have been on a different day or even the following year, September 18 has been the day traditionally celebrated.21,22 (Figure 2)

Fig 2.

This is an excerpt from an early newsletter published by Palmer, including the testimonial from Harvey Lillard, who reportedly was deaf for many years.22

The Birth of Chiropractic Celebrated

By 1897, Palmer's school was just starting; thus, it was unlikely the birthday of the profession was celebrated that year. There were only 3 chiropractors at that time.23 Over the next several decades, the fledgling chiropractic profession would be fighting to survive when restrictive medical licensing laws deemed that its practice was considered illegal.24 Early doctors of chiropractic focused on establishing legislation and fighting battles in the courtroom.25

In 1905, the founder spoke at the Palmer School and Infirmary of Chiropractic (now known as the Palmer College of Chiropractic) June commencement ceremonies. 26 He reminisced about recent events and marveled at how the profession had grown. "Little did I think nine and a half years ago, " said the doctor, "that I would see chiropractic reach such remarkable dimensions in so short a time. I never dreamed that within this short period our school would have 200 graduates and a class of 18 in one year."26

In 1913, D.D. Palmer died unexpectedly of typhoid fever, leaving others to carry on the tradition of telling the tale of the first chiropractic adjustment.27 In the same year, chiropractic gained ground in professional recognition. Kansas was the first state to pass a chiropractic licensing act, although it would not be until 1974 that the last state (Louisiana) in the US would legally recognize chiropractic. 28,29

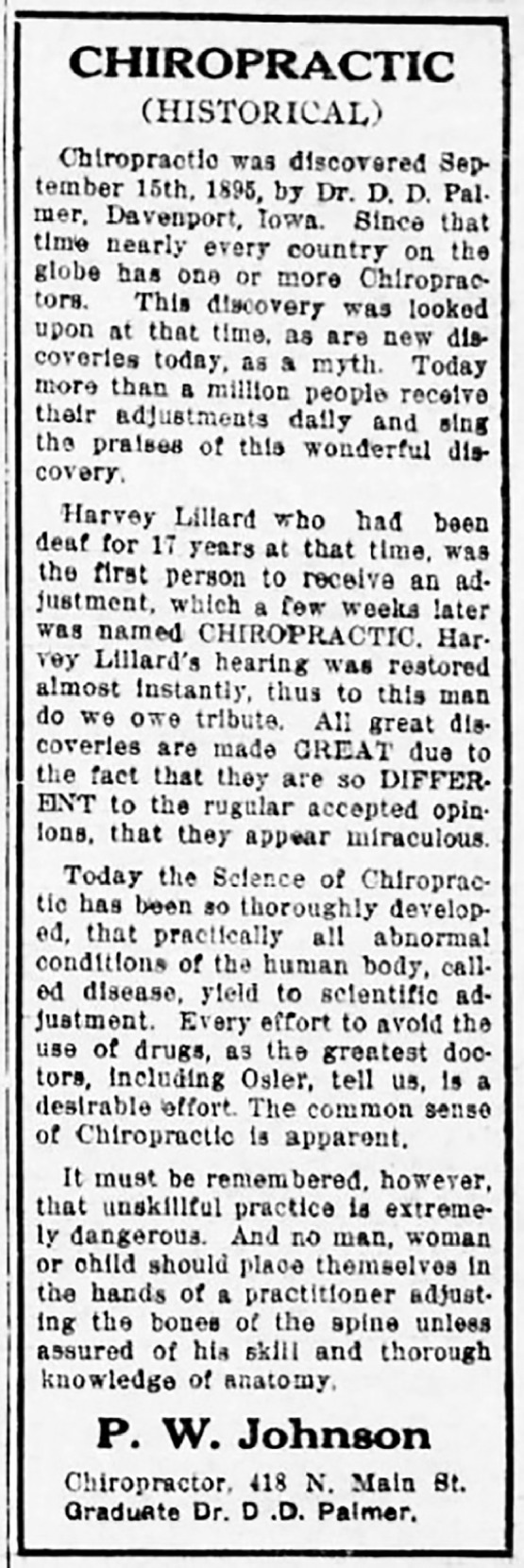

The early years were challenging and the date of chiropractic's founding seemed to help fortify solidarity within the newly founded chiropractic profession. Early announcements about the birth of the profession were included in chiropractic advertisements. Since the profession was still emerging, these public announcements may have been produced to set professional precedence and to try to legitimize chiropractic practice in the eyes of the public. Some of these materials mentioned Harvey Lillard's tale about the cure of his deafness after several chiropractic adjustments to his spine and further described chiropractic in order to familiarize readers with this new profession.30 An example of an advertisement from 1915 includes a description of the birth of chiropractic.30 (Figure 3)

Fig 3.

A newspaper advertisement from a graduate of Dr. D.D. Palmer. Note the typo in the date, which should read September 18.

Eight years after his death, the dedication ceremony for D.D. Palmer's memorial bust was held at the Palmer campus in Davenport, Iowa in 1921. In addition to discussing the life of D.D. Palmer, people who knew him recounted stories about the first chiropractic adjustment and the speakers hailed September 18 as the founding date. (Figure 4)

Fig 4.

A postcard of the monument to the memory of the founder of the Palmer School of Chiropractic, Davenport, Iowa.

As time passed, some chiropractors desired to have a more formal recognition of the birth of chiropractic. In 1928, Wray Hughes Hopkins, DC, reported that he conceived of a plan to celebrate chiropractic and presented his idea to Dr. Bartlett Joshua Palmer, President of the Palmer School of Chiropractic in Davenport.31 The aim of the celebration was to have chiropractors from around the world observe the annual event and “to identify themselves with the world's greatest natural healing science.” 32 He envisioned that there would be lectures, radio broadcasts, newspaper or magazine articles, and advertisements in local newspapers. B.J. Palmer supported the idea and Hopkins stated that the first global Chiropractic Day event was commemorated on September 18, 1928.32

As the years continued, so did the celebrations. On September 18, 1945, chiropractic's 50th golden anniversary was commemorated. An announcement in a Texas newspaper read "Today marks the beginning of the celebration of Chiropractic's Fiftieth (Golden) Anniversary year. And over the nation Chiropractors and their patients are giving thanks for the founding of the profession which has done so much in so short a time to alleviate the illnesses and suffering of mankind."33

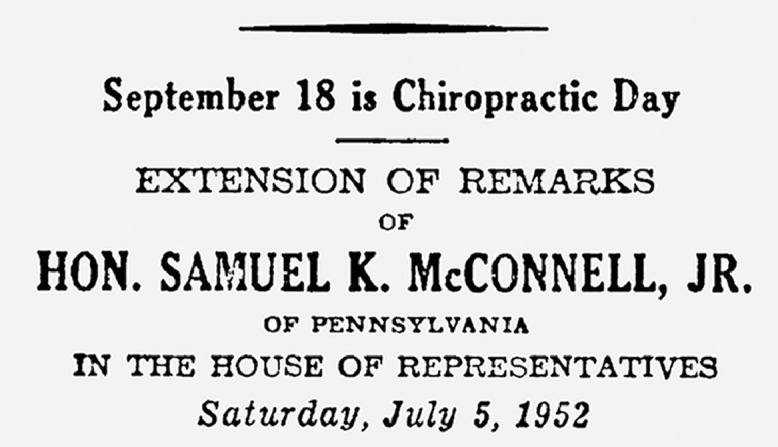

By the 1950s, it was estimated that there were approximately 23,000 chiropractors in North America and chiropractic claimed to be “the second largest profession of healing” in the United States.34 At that time, it was suggested that 33,000,000 patients received chiropractic care each year in North America. 34 The United States Congressional Record of 1952 declared Chiropractic Day as a day “to mark observance of the historical date on which Dr. Daniel David Palmer rediscovered the principles of chiropractic and gave a new science of healing to the world. Endorsed and sponsored by the National Chiropractic Association and other professional organizations, Chiropractic Day is internationally observed each September 18 by chiropractors.”34 (Figure 5)

Fig 5.

Image from the original document declaring Chiropractic Day in the US Congressional record.

Samuel K. McConnell, Jr., Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 16th congressional district, read aloud the presentation written by Hopkins. This 1952 announcement is assumed to be the first known official US congressional recognition of Chiropractic Day. The statement reminisced about the story of the treatment attributed to be the first chiropractic adjustment.34

“All chiropractors know the story of Dr. Palmer's first adjustment of Harvey Lillard, and of how Lillard, who had suffered from an approximate 90-percent loss of hearing acuity for 20 years, was found by careful and impartial examination at the hands of his own medical physician, Dr. A. B. Hender, to have recovered his full auditory capacity after treatment by Dr. Palmer.

The basic principle of chiropractic is the premise that the nerve system controls all other systems and physiological functions of the human body, and that interference with the nerve control of these systems impairs their proper functioning and induces disease by rendering the body less resistant to infection or other existing causes.

The chiropractor is a physician—a special kind of physician, and as such is engaged in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of disease and in the promotion of public health and welfare.”34

As the years continued, so did the celebrations on September 18.35, 36, 37, 38 Likely because the day belongs to the chiropractic profession as a whole and to no particular organization or association, September 18 has been called many different names over the past 125 years. These include Chiropractic Rally Day, Chiropractic Anniversary, Chiropractic Founder's Day, Chiropractic Discovery Day, Chiropractic Celebration and Chiropractic Day. Celebrations have continued at various chiropractic schools, universities, associations, and practices as an annual event to celebrate the birth of the profession.

Chiropractic is a Profession Worth Celebrating

Chiropractic continues to grow throughout the world. In 2017, there were approximately 103,000 chiropractors practicing throughout the world, a majority (74.4%) were located in the US. 24,39 Chiropractors are active in various aspects of health care and have been integrated in a variety of health care settings.24,40, 41, 42 And, chiropractors have been part of interdisciplinary teams that have contributed to global efforts to improve spine care.43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50

Chiropractors are best known for helping people with neuromusculoskeletal complaints, especially of the spine. They have a variety of practice styles and use a range of techniques and modalities to care for patients.51 In the United States, doctors of chiropractic are distinct from other medical providers in that they have separate licensure and most do not use drugs or surgery in practice. Although there is a variety of chiropractic viewpoints and opinions about scope of practice, overall the public tends to associate chiropractic with care of the spine and a holistic style of healthcare.52

More and more people are seeking out chiropractic care. In the US, approximately 14% of the population has consulted a chiropractor annually and the number of people seeking chiropractic care continues to grow. 53, 54, 55, 56 A majority of US adults believe that chiropractic care is effective for back and neck pain and a majority believe that chiropractors are trustworthy. As well, patients report high satisfaction ratings for care provided by doctors of chiropractic.52,57, 58, 59

Chiropractors have developed and contributed to science-based guidelines and a majority in the US report practicing with evidence-based methods.24 For example, best practice evidence for chiropractic care includes: adults with headache,60 adults with neck pain,61 chronic spine-related conditions, 62 fibromyalgia syndrome, 63 health promotion, disease prevention, and wellness, 64 imaging practice guidelines, 65, 66, 67, 68 low back pain,69 lower extremity conditions, 70 myofascial trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome, 71 neck pain-associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders, 72 and upper extremity disorders.73

Based on its origins, it is not surprising that the procedure most associated with this profession is chiropractic spinal manipulation (ie, spinal adjustments).52,74 Chiropractic has been shown to be cost effective for many musculoskeletal conditions75 and to reduce pain and functional disability for patients with chronic low back pain. 76 It has been suggested that integration of chiropractic services results in decreased cost and improved health outcomes for some conditions compared with conventional medical approaches.77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86 Many medical guidelines for back pain include spinal manipulation, which is a mainstay in chiropractic treatment methods. 87, 88, 89, 90 Thus, this profession has much to contribute to helping people with various health concerns.

Celebrating Chiropractic Day

Chiropractic has come a long way since 1895 and our origins are worth celebrating. Chiropractors should pause to remember what our predecessors did in the past that have enabled us to practice and serve the public in the present. The following are some suggestions to consider when celebrating Chiropractic Day. These activities could be implemented for a day or an entire month, are low cost or free, and can be very rewarding.

Celebrate by educating

Chiropractic began with the earliest diplomas commanding graduates to go forth and to “teach and practice” chiropractic. 91 We should teach others about what chiropractic currently is and where it comes from. Since the first program was established, chiropractic education has continued to grow and improve. 23,92, 93, 94, 95 To celebrate Chiropractic Day, consider educating others about chiropractic.

-

1.

Give a lecture about chiropractic and health at your local community center or other organization.

-

2.

Help our next generation of chiropractors by mentoring a chiropractic student.

-

3.

Write an article about chiropractic for your local news media.

-

4.

Display a poster or flier in your practice or in your community to remind people about Chiropractic Day. In the online supplemental material, full versions of these fliers/posters are available to you for free to download and use. (Figure 6)

Fig 6.

Modern fliers that announce Chiropractic Day. These are available for free to download from the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities website.

Celebrate by learning

Learn more about past and current events. As D.D. Palmer had continued to learn throughout his lifetime, chiropractors value ongoing improvement and lifelong learning. To celebrate Chiropractic Day, consider investing in your knowledge.

-

1.

Learn more about new research being published by chiropractors and others relating to chiropractic practice. If you are not already a subscriber of our chiropractic scientific journals, consider subscribing. There are many evidence-based articles relevant to practice. By subscribing you get to stay up to date on current science and knowledge within chiropractic.

-

2.

Marvel at the body's amazing capacity to heal. Learn more about the body's capabilities, such as homeostatic mechanisms or relationships between structure and function.

-

3.

Learn new information about the nervous and musculoskeletal systems and all of their capabilities.

-

4.

Learn more about the intricate relationships within the biopsychosocial model of care and how these factors relate to chiropractic.

-

5.

Discover information about the history of chiropractic. Read journal articles about chiropractic, such as those found in the journal published by the Association for the History of Chiropractic (www.historyofchiropractic.org) or the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities.96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101

-

6.

Read historical chiropractic books that provide insight into chiropractic history and how those events relate to today.20,23,25,102, 103, 104, 105, 106

-

7.

Host a learning event, such as a book club or a lunch-and-learn, to discuss interesting chiropractic topics.

Celebrate by honoring

Honor those who have supported and developed chiropractic. Take time to reflect on the contributions and efforts of the people who have worked for over a century to help bring chiropractic to the world so that you may practice today. Honor our forebearers and appreciate the work and sacrifices that early chiropractors made so that chiropractic care is now legal and accessible. Remember that in some countries, the struggle to recognize chiropractic is still ongoing. To celebrate Chiropractic Day, consider honoring those who have come before you.

-

1.

Reach out to those who mentored you during your development as a chiropractor. Thank people who supported you, including those who might not be chiropractors. Send them a note, an email, or reach out to them by phone, thanking them for guiding you on your career path.

-

2.

Reach out to teachers who taught you during your chiropractic program. Let your favorite faculty member know how much he or she meant to you as you were developing as a student or young doctor.

-

3.

Reach out to those chiropractors who are in your local region. Find members in your chiropractic association who have been practicing the longest. Send them a note thanking them for their service to the profession. Consider organizing an annual celebration for those who have served the longest in your association.

-

4.

Dedicate a memorial donation to someone in the profession who has contributed but who may have passed. Consider donating in their honor to your favorite charity or to a non-profit chiropractic organization that supports research and education, such as to the NCMIC Foundation (www.ncmicfoundation.org).

Celebrate by volunteering

The chiropractic profession has helped people since the profession began and continues to look for ways to do additional outreach. Since the beginning of the profession, chiropractors have focused on helping people, providing what is best for patients and communities.107,108 To celebrate Chiropractic Day consider volunteering.

-

1.

Volunteer for a local charity that you are interested in, such as one that helps to feed the homeless, help foster children, or assist those experiencing domestic violence. Pick a charity that is meaningful to you.

-

2.

Volunteer for your chiropractic association, such as being on a committee or workgroup.

-

3.

Volunteer to help with teaching children, such as a local literacy program or other educational support.

-

4.

Identify your area of interest and match it with a charity. For example, if one of your family members has Alzheimer's disease or breast cancer, consider finding a relevant charity to which you can donate your time or service.

Celebrate by engaging

Chiropractic would not be where it is today if it were not for individual chiropractors engaging in constructive and helpful work that advanced the profession. To celebrate Chiropractic Day, consider engaging by finding your strengths and applying them. Identify an interest or a strength that you have, then find a chiropractic association that matches. Chiropractic organizations need your participation to help make chiropractic even stronger. Many associations have both tangible (eg, discounts, newsletters) and intangible (eg, networking opportunities) benefits. Often the cost of membership is far less than what we gain by joining and participating. To celebrate Chiropractic Day, if you are not already a member of an association, consider joining one or more in areas of your interest. Here are some suggestions.

-

1.

If you are good at debating or convincing others of your viewpoints, consider joining your regional or national chiropractic association.

-

2.

If you are interested in learning more about history, consider joining the Association for the History of Chiropractic (www.historyofchiropractic.org).

-

3.

If you are interested in public health, consider joining the Chiropractic Health Care section of the American Public Health Association (www.apha.org).

-

4.

If you are interested in one of the chiropractic specialties (eg, pediatrics, sports, nutrition, diagnostic imaging, orthopedics, and others), consider joining that chiropractic specialty group.

Celebration of Chiropractic Day should be easy and fun. The day gives us time to remember our roots, to appreciate the present, and to look forward to the future. Regardless how you choose to celebrate Chiropractic Day, make it your own. It is certainly a day worth celebrating.

Limitations

This is a narrative, descriptive report and only provides a singular viewpoint of historic events. Attempts were made to provide a broad view. However, other authors may have differing opinions about the interpretations of these events. It is recognized that the information reported here is only 1 viewpoint.

Conclusion

The chiropractic profession celebrates its birth on September 18. Regardless of the many different names used over the past 125 years, the celebration of Chiropractic Day provides an opportunity to reflect on how far the profession has come and how chiropractors continue to serve patients and their communities.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources were reported for this study. The author (CDJ) is the editor of the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities, a member of the Association for the History of Chiropractic, a member of her national chiropractic association, the American Public Health Association, and she is a member of the NCMIC Board. She has no affiliation or financial relationships with the NCMIC Foundation, Association for the History of Chiropractic board, or the American Public Health Association.

Contributorship

Concept development: CDJ

Supervision: CDJ

Literature search: CDJ

Writing: CDJ

Critical review: CDJ

Practical Applications.

-

•

The chiropractic profession celebrates its birthday on September 18.

-

•

The profession has been celebrating Chiropractic Day for the majority of its history.

-

•

There are many activities that chiropractors could do to celebrate Chiropractic Day.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.echu.2020.11.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonald L. Florence Nightingale and the early origins of evidence-based nursing. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2001;4(3):68–69. doi: 10.1136/ebn.4.3.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yapijakis C. Hippocrates of Kos, the father of clinical medicine, and Asclepiades of Bithynia, the father of molecular medicine. in vivo. 2009;23(4):507–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gevitz N. A degree of difference: the origins of osteopathy and first use of the "DO" designation. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014;114(1):30–40. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2014.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sneader W. The discovery of aspirin: a reappraisal. Bmj. 2000;321(7276):1591–1594. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7276.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aminov RI. A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Frontiers in microbiology. 2010;1:134. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ligon BL. Penicillin: its discovery and early development. Seminars in pediatric infectious diseases. 2004;15(1):52–57. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill AB. Memories of the British streptomycin trial in tuberculosis: the first randomized clinical trial. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11(2):77–79. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90001-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starr P. Basic Books; New York: 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock C. Risk, Responsibility and Surgery in the 1890s and Early 1900s. Medical history. 2013;57(3):317–337. doi: 10.1017/mdh.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan RB. Sanguine practices: a historical and historiographic reconsideration of heroic therapy in the age of Rush. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 1994;68(2):211–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith CM. Origin and uses of primum non nocere—above all, do no harm! The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005;45(4):371–377. doi: 10.1177/0091270004273680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donahue JH. D. D. Palmer and innate intelligence: development, division and derision. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue JH. D. D. Palmer and the metaphysical movement in the 19th century. Chiropr Hist. 1987;7(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue JH. The man, the book, the lessons: the chiropractor's adjuster, 1910. Chiropr Hist. 1990;10(2):35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MD. Old Dad Chiro: his thoughts, words, and deeds. J Chiropr Humanit. 2009;16(1):57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer DD. Beacon Light Press; Los Angeles, Calif: 1914. The Chiropractor. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keating JC. The evolution of Palmer's metaphors and hypotheses. Philosophical Constructs for the Chiropractic Profession. 1992;2:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer DD. 1896. The Magnetic Cure. January 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer DD. The First Chiropractic Patient. The Chiropractor. 1904 December 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland: 1910. The Chiropractor's Adjuster: A Textbook of the Science, Art and Philosophy of Chiropractic for Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troyanovich S, Troyanovich J. Reflections on the birth date of chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 2013;33(2):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lillard H. Deaf Seventeen Years. The Chiropractic. 1897 January 1897. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating JC, Callender AK, Cleveland CS. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport: 1998. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America: Report to the Council on Chiropractic Education. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Himelfarb I, Hyland J, Ouzts N. 2020. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020.https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/ Published. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardwell WI. Mosby-Year Book; St. Louis: 1992. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Class Graduates at Palmer School. The Daily Times. 1905;1905:10. June 24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siordia L, Keating JC. Laid to uneasy rest: DD Palmer, 1913. Chiropr Hist. 1999;19(1):23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bower N, Hynes R. Going to Jail for Chiropractic: A Career's Defining Moment. Chiropr Hist. 2004;24(2) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm WS. Kansas coconuts: legalizing chiropractic in the first state, 1910-1915. Chiropr Hist. 1995;15(2):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson PW. Chiropractic (Historical) The Hutchinson News. 1915;1915:12. Aug 07. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopkins WH. Chiropractic Day - A National Event. The Chiropractor. 1929 November 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopkins WH. Vol. 37. 1941. Chiropractic Day, 1941; p. 13. (The Chiropractor). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephens Chiropractic 50th Golden Anniversary Year. Lubbock Morning Avalanche. 1945 September 8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McConnell J, S.K. Vol Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 82nd Congress Second Session Appendix Volume 98, Part 11, page A-4608. 1952. September 18 is Chiropractic Day Extension of Remarks Of Hon. Samuel K. Mcconnell, Jr. of Pennsylvania in the House Of Representatives, Saturday, July 5, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiropractic Day Wednesday. Longview News-Journal. 1963;1963:3. September 17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiropractic Day Held At Stadium. The Morning Herald. 1973;1973 September 5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiropractic Day - September 18, 1895. The Lompoc Record. 1982;1982 September 17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow L. Hands that Heal: Non-invasive treatement has slowly moved into the mainstream. Quad-City Times. 1995;1995 September 11. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green BN, Johnson CD, Brown R. An international stakeholder survey of the role of chiropractic qualifying examinations: A qualitative analysis. J Chiropr Educ. 2020;34(1):15–30. doi: 10.7899/JCE-19-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson CD, Green BN, Konarski-Hart KK. Response of Practicing Chiropractors during the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Descriptive Report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson C, Rubinstein SM, Cote P. Chiropractic care and public health: answering difficult questions about safety, care through the lifespan, and community action. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(7):493–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S. The Global Spine Care Initiative: public health and prevention interventions for common spine disorders in low-and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):838–850. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):925–945. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R. The Global Spine Care Initiative: classification system for spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):889–900. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R. The Global Spine Care Initiative: care pathway for people with spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kopansky-Giles D, Johnson CD, Haldeman S. The Global Spine Care Initiative: resources to implement a spine care program. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):915–924. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M. The Global Spine Care Initiative: methodology, contributors, and disclosures. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):786–795. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg CK, Green B, Moore J. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: A systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/2156587215621461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang M. The chiropractic scope of practice in the United States: a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(6):363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Public perceptions of doctors of chiropractic: results of a national survey and examination of variation according to respondents' likelihood to use chiropractic, experience with chiropractic, and chiropractic supply in local health care markets. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(8):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meeker WC. Public demand and the integration of complementary and alternative medicine in the US health care system. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(2):123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(00)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002. Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 2005;11(1):42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zodet MW, Stevans JM. The 2008 prevalence of chiropractic use in the US adult population. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(8):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hertzman-Miller RP, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL. Comparing the satisfaction of low back pain patients randomized to receive medical or chiropractic care: results from the UCLA low-back pain study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(10):1628–1633. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherkin DC, MacCornack FA. Patient evaluations of low back pain care from family physicians and chiropractors. Western Journal of Medicine. 1989;150(3):351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kane R, Olsen D, Leymaster C, Woolley FR, Fisher FD. Manipulating the patient a comparison of the effectiveness of physician and chiropractor care. The Lancet. 1974;303(7870):1333–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bryans R, Descarreaux M, Duranleau M. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(5):274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bryans R, Decina P, Descarreaux M. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(1):42–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farabaugh RJ, Dehen MD, Hawk C. Management of chronic spine-related conditions: consensus recommendations of a multidisciplinary panel. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(7):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider M, Vernon H, Ko G, Lawson G, Perera J. Chiropractic management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(1):25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hawk C, Schneider M, Evans MW, Jr., Redwood D. Consensus process to develop a best-practice document on the role of chiropractic care in health promotion, disease prevention, and wellness. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(7):556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bussieres AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA. Diagnostic imaging guideline for musculoskeletal complaints in adults-an evidence-based approach-part 2: upper extremity disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(1):2–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bussieres AE, Peterson C, Taylor JA. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults–an evidence-based approach: introduction. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(9):617–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bussieres AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults-an evidence-based approach-part 3: spinal disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(1):33–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bussieres AE, Taylor JA, Peterson C. Diagnostic imaging practice guidelines for musculoskeletal complaints in adults–an evidence-based approach. Part 1. Lower extremity disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(9):684–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F. Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments for Low Back Pain: A Guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(4):265–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brantingham JW, Bonnefin D, Perle SM. Manipulative therapy for lower extremity conditions: update of a literature review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(2):127–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vernon H, Schneider M. Chiropractic management of myofascial trigger points and myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F. The Treatment of Neck Pain-Associated Disorders and Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Clinical Practice Guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8) doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.08.007. 523-564 e527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brantingham JW, Cassa TK, Bonnefin D. Manipulative and multimodal therapy for upper extremity and temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36(3):143–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manga P. Economic case for the integration of chiropractic services into the health care system. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(2):118–122. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(00)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M. Cost-effectiveness of medical and chiropractic care for acute and chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(8):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarnat RL, Winterstein J, Cambron JA. Clinical utilization and cost outcomes from an integrative medicine independent physician association: an additional 3-year update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grieves B, Menke JM, Pursel KJ. Cost minimization analysis of low back pain claims data for chiropractic vs medicine in a managed care organization. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM. Cost of care for common back pain conditions initiated with chiropractic doctor vs medical doctor/doctor of osteopathy as first physician: experience of one Tennessee-based general health insurer. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(9):640–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Houweling TA, Braga AV, Hausheer T, Vogelsang M, Peterson C, Humphreys BK. First-contact care with a medical vs chiropractic provider after consultation with a swiss telemedicine provider: comparison of outcomes, patient satisfaction, and health care costs in spinal, hip, and shoulder pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(7):477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Field JR, Newell D. Clinical Outcomes in a Large Cohort of Musculoskeletal Patients Undergoing Chiropractic Care in the United Kingdom: A Comparison of Self- and National Health Service-Referred Routes. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weeks WB, Leininger B, Whedon JM. The Association Between Use of Chiropractic Care and Costs of Care Among Older Medicare Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain and Multiple Comorbidities. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.01.006. 63-75 e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilkey D, Caddy L, Keefe T. Colorado workers' compensation: medical vs chiropractic costs for the treatment of low back pain. J Chiropr Med. 2008;7(4):127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stano M. A comparison of health care costs for chiropractic and medical patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16(5):291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stano M, Haas M, Goldberg B, Traub PM, Nyiendo J. Chiropractic and medical care costs of low back care: results from a practice-based observational study. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(9):802–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stano M, Smith M. Chiropractic and medical costs of low back care. Medical care. 1996:191–204. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chou R. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(8):606–607. doi: 10.7326/L17-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chou R, Cote P, Randhawa K. The Global Spine Care Initiative: applying evidence-based guidelines on the non-invasive management of back and neck pain to low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):851–860. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, Brown K, Deyo R. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1994. Acute Low Back Pain in Adults: Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 169. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2012-00014-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 16-EHC004-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; February 2016. Available at:www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 91.Senzon SA. Chiropractic professionalization and accreditation: an exploration of the history of conflict between worldviews through the lens of developmental structuralism. J Chiropr Humanit. 2014;21(1):25–48. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gibbons RW. The rise of the chiropractic educational establishment 1897-1980. In: Lints-Dzaman F, editor. Who's Who in Chiropractic International. Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Company; Littleton, CO: 1980. pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ferguson A, Wiese G. How many chiropractic schools? An analysis of institutions that offered the D.C. degree. Chiropr Hist. 1988;9(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gibbons RW. Chiropractic's Abraham Flexner: the lonely journey of John J. Nugent, 1935-1963. Chiropr Hist. 1985;5:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Keating JC. Before Nugent took charge: early efforts to reform chiropractic education, 1919–1941. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2003;47(3):180–216. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson C. A brief review of the evolution of the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities: a journey beginning in 1991. J Chiropr Humanit. 2009;16(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Joseph C, Keating J. The influence of World War I upon the chiropractic profession. J Chiropr Humanit. 1994;4:36–55. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johnson C. Reflecting on 115 years: the chiropractic profession's philosophical path. J Chiropr Humanit. 2010;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Senzon SA. Constructing a philosophy of chiropractic I: an Integral map of the territory. J Chiropr Humanit. 2010;17(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Senzon SA. The Chiropractic Vertebral Subluxation Part 1: Introduction. J Chiropr Humanit. 2018;25:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Winterstein J. Journal of Chiropractic Humanities: A Celebration of 25 Volumes. J Chiropr Humanit. 2018;25:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Keating JC. B.J. of Davenport: the early years of chiropractic. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, Iowa: 1997. Association for the History of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Keating JC, Sportelli L, Siordia L. NCMIC Group Inc; Clive: 2004. We Take Care of Our Own: NCMIC and the Story of Malpractice Insurance in Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Keating JC, Liewer DM. I. Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards; Greeley: 2012. (Protection, Regulation and Legitimacy: FCLB and the Story of Licensing in Chiropractic). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moore JS. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1993. Chiropractic in America: The History of a Medical Alternative. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gielow V. Fred H. Barge; 1981. Old dad chiro: Biography of DD Palmer, founder of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Johnson C. Poverty and human development: contributions from and callings to the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(8):551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stevens GL. Demographic and referral analysis of a free chiropractic clinic servicing ethnic minorities in the Buffalo, NY area. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(8):573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.