Abstract

This paper summarizes the 2020 Diversity in Radiology and Molecular Imaging: What We Need to Know Conference, a three-day virtual conference held September 9–11, 2020. The World Molecular Imaging Society (WMIS) and Stanford University jointly organized this event to provide a forum for WMIS members and affiliates worldwide to openly discuss issues pertaining to diversity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). The participants discussed three main conference themes, “racial diversity in STEM,” “women in STEM,” and “global health,” which were discussed through seven plenary lectures, twelve scientific presentations, and nine roundtable discussions, respectively. Breakout sessions were designed to flip the classroom and seek input from attendees on important topics such as increasing the representation of underrepresented minority (URM) members and women in STEM, generating pipeline programs in the fields of molecular imaging, supporting existing URM and women members in their career pursuits, developing mechanisms to effectively address microaggressions, providing leadership opportunities for URM and women STEM members, improving global health research, and developing strategies to advance culturally competent healthcare.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11307-021-01610-3.

Key words: Diversity, Radiology, Molecular imaging, STEM

Introduction

The goal of the 2020 Diversity in Radiology and Molecular Imaging Conference was to facilitate meaningful discussions related to diversity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) that would lead to lasting change for individuals who are underrepresented in STEM fields and molecular imaging in particular, including women and underrepresented minorities (URMs; i.e., those who have self-identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander). We strongly believe that every member of our community, regardless of ability/disability, race, gender, background, religion, sexual orientation, or mental health status, should have the opportunity to thrive in a supportive, inclusive, and diverse professional setting.

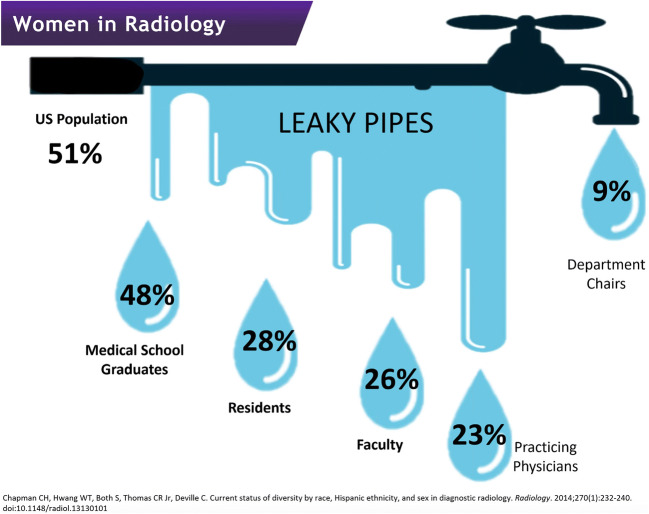

One central theme that emerged throughout all presentations and roundtable discussions was the need for role models, mentors, and sponsors for underrepresented members in STEM fields. While overlap may arise between role models and mentors, each is considered a distinct role in drawing and retaining underrepresented members into STEM fields. Panelists defined role models as those who can be drawn upon for inspiration and reassurance that they, as underrepresented individuals in STEM, are not alone in the field and, further, that they too can succeed. Panelists concluded that greater visibility of women and URMs within the field might inspire future molecular imaging scientists and clinicians. Diverse role models increase motivation and confidence in trainees and allow them to “see themselves” following a similar career path [1–4]. This perspective was following reports by Dennehy and Dasgupta, who enrolled women in pipeline programs during their first 2 years of college—a critical time of recruitment to STEM majors—and concluded that “the benefits of peer mentoring endured long after the intervention had ended” [1]. Panelists considered a mentor as someone senior within a field who actively works with a more junior member to develop the skills needed to succeed within that field. Panelists agreed that efforts should be made to make mentorship programs and opportunities available not just to trainees but also to early- and mid-career women and URM members, with the goal of closing the “leaky pipe” (Fig. 1), a phenomenon in which group members progressively leave a field over time. While the “leaky pipe” phenomenon has been observed in multiple situations (e.g., early science education), we noted a “leaky pipe” of women who successively drop out of radiology careers with increasing academic rank. During the conference, a significant point of discussion during the conference was the importance of introducing STEM as a viable and attractive career path to URM members early on, ideally starting in grade school, to partially remedy the “leaky pipe.” Finally, panelists discussed the need for sponsors to actively support a higher representation of women and URM members in senior and leadership positions. In this context, we defined sponsors as organizations or individuals that provide financial, service, or material support to help underrepresented members in STEM succeed.

Fig. 1.

Although women make up nearly 50 % of medical school graduates, as seniority increases, women are less represented with less than 10 % of radiology chairs being women. We need to develop solutions to fix this “leaky pipe” of career progression (Figure from [5]). The study was performed on 2010 data with 541 radiology residents included. Data sources had US population data from the US Census Bureau, practicing physician data from the American Medical Association, medical school graduate data from the American Association of Medical Colleges, and residency data from [6–9]. The authors state that “for race and ethnicity measures, unduplicated totals were provided for U.S. census, medical school graduates, and residents and fellows for race and ethnicity separately. For other data sources, Hispanic individuals were included in the “other” racial category because no breakdown by race was provided.” [5]

A second major theme that arose from the discussions was the need for STEM clinicians and scientists to better serve an increasingly diverse community. This aim entails striving for culturally competent or proficient healthcare in the clinical setting and increasing the diversity of the populations studied by scientists, as the current lack of diversity in studied populations [10–14] results in worse outcomes for Black and Hispanic community members. A major hurdle lies in recruiting and retaining these individuals in clinical studies [15–17]. The cause of this hurdle is multifaceted and includes “mistrust of researchers and the government, lack of transportation, fear of exploitation, and low levels of familiarity with medical research” [15]. These fears are not without merit and, in fact, are predicated on numerous egregious historical violations and exploitations [18, 19] of these communities. Thus, the burden lies firmly with researchers to ease these rightful concerns and make a concerted effort for inclusion. Furthermore, participation in a research study disproportionately burdens members of low-income communities [20] through a multitude of factors including physical accessibility (e.g., lack of resources to travel to a research site) and time constraints (e.g., less job-related flexibility), hindering their ability to participate in medical research studies.

The virtual conference received 908 views as of the end of September 2020, with 514 attendees who actively participated in the live event and 394 people who viewed the conference content through the online portal (https://www.wmislive.org/). Conference attendees comprised a wide range of demographic/ethnic backgrounds and included clinical and community radiologists, basic scientists, and researchers in the field of molecular imaging. The main topics of the event were racial diversity in STEM, challenges faced by women in STEM fields, and global health. Participants discussed these primary topics via seven plenary lectures, twelve scientific presentations, and nine roundtable discussions. The following summaries of the key conference themes provide an excerpt of “take-home points” from the scientific sessions (abstracts of the scientific sessions are presented in the Supplementary Materials) and roundtable discussions.

Increasing Racial Diversity in STEM

Dr. Kassa Darge reflected on the low rate of URM members in the field of molecular imaging and clinical medical imaging. Black trainees and faculty typically comprise approximately 4–7 % of all trainees and faculty within STEM fields, with only ~2 % within radiology [5]. Numerous extrinsic and intrinsic factors contribute to this underrepresentation. One factor is a lack of academic mentorship. Mentoring is a critical element for faculty career advancement in academic medicine, including radiology. Dr. Darge discussed the critical importance and impact of mentoring on enhancing diversity and inclusion in an academic radiology department.

Dr. Daniel Chonde presented challenges faced by hospital-based diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) committees. These committees [1] are charged with ensuring equitable access to care regardless of race, gender, age, etc., while also promoting diversity within the workforce [21]; [2] have historically been devalued financially and in their ability to affect policy [22]; and [3] rely largely on volunteerism, which limits access to technical expertise [23]. While the business literature has described increased innovation [24], institutional experience has demonstrated that the majority of DEI volunteers have similar skillsets.

Unlike DEI initiatives, a significant increase has arisen for hospital-based innovation centers and their funding [25]. A major benefit of these hospital innovation centers is their ability to engage frontline workers (e.g., nurses, physicians) in the innovation process [26]. Working with a clinical staff, these incubators assist in bringing products to market that can potentially create revenue. Separately, previous work has shown that continuous improvements in health technology have benefited marginalized populations [27, 28].

How to increase URM representation and inclusion in STEM

A central discussion point in this session was the importance of introducing STEM as a viable and attractive career path to URMs early on, ideally starting in grade school. Similarly, dedicated career development programs should provide high school students with shadowing opportunities at universities, giving them firsthand exposure to the scientific problems currently being worked on and informing them on the necessary skills they may need for a career in STEM. The notion of “seeing is believing” supports the idea that it is important for young URM students to see scientists, physicians, and engineers who look like them, thereby fostering a belief that they too could pursue such a career. In addition, seeing URM members in STEM positions promotes the perception of belonging to individual STEM groups (e.g., a lab) and to STEM as a whole. To this end, school outreach programs, particularly in disadvantaged schools, could provide URMs with important exposure to STEM fields at an early age. STEM trainees and faculty at universities should receive recognition for connecting with the broader community. For students from financially disadvantaged backgrounds, financial support for internships and shadowing opportunities is critically important in order to make these programs attainable.

Among training programs for 20 subdisciplines in medicine, diagnostic radiology ranks 17th in women and 20th in URM representation [5]. Thus, there is an urgent need for radiology to address its dire underrepresentation of URM trainees. A significant factor in this disparity may arise from URM students not feeling “seen” by faculty mentors. A greater effort should be made to assist mentors in understanding the unique challenges faced by URM students, including pressures from home, financial burdens, and family challenges. Often, URM students deal with these pressures in silence while attempting to balance research and educational responsibilities. One solution would be enhancing efforts to create or expand URM-directed mentorship. This approach would significantly enhance the experiences and future directions of the URM student population. In principle, the interdisciplinary nature of the radiology and medical imaging fields offers the opportunity to draw students from a wide variety of scientific disciplines including math, engineering, and computer science. Therefore, it may be helpful to reach out to undergraduates majoring in such areas, in addition to the more traditional life science departments, introducing the field of radiology at an early time, when they are starting to consider applying to medical schools or graduate programs. Although an increasing number of research and internship opportunities are available at this stage, being able to provide funding for URMs would increase the likelihood of these students being able to participate in such programs. Such programs could also help URMs foster connections with other peers or colleagues that may be slightly ahead of them—such as graduate students and postdocs—who can often offer insight and support, encouraging them to stay in STEM fields. Furthermore, it is imperative that efforts are made to ensure that mentors continue their relationship with mentees, even if at a reduced level, after the completion of their formal program to provide continued encouragement and support to retain these members in the field.

The digital divide—the large disparity between individuals who have easy access to computers and the internet and those who do not—is an obstacle for recruiting URMs to STEM fields. Without ready access to computers or the internet, it is substantially more difficult to acquire or develop technical skills, which would otherwise come naturally from the repeated use of technology. As there is an increasing need for more technical skills throughout all levels of medical imaging and STEM fields, it is important for these skills to be developed early on. Yet, exposure to technical skills can vary regionally (e.g., Silicon Valley versus rural areas). More recently, the dramatic shift toward virtual learning has also highlighted the importance of ensuring that students have access to computer resources and reliable internet connections. Thus, while an enhanced social media presence of STEM institutions presents opportunities for an increased reach to a subset of URM students, institutions must recognize that a significant portion of the URM students they wish to reach may not have easy (or any) access to social media due to socioeconomic challenges.

Lastly, this discussion emphasized the importance of both structured and unstructured mentorships as essential factors in recruiting URMs to STEM programs, a notion further supported by research [29]. A structured mentorship typically involves actionable items to achieve measurable goals, often with requirements and milestones set at the beginning of the relationship. Unstructured mentoring is more informal; goals and interim requirements are still usually defined but are not always measurable or rigidly incorporated. Advice provided for finding good mentors included meeting and getting to know a variety of people at one’s institution, preferably on a one-on-one basis, accepting as many invitations as possible for professional events, and being persistent in seeking connections. An interesting point that arose during this discussion was the importance of helping URMs develop what are commonly known as “soft skills” to facilitate networking, make the most of mentoring opportunities, and build strong collegial relationships with peers. As such, it would be beneficial to provide workshops or activities that help URMs to build these nontechnical skills, which can include effective communication, listening, leadership, and motivational skills [30] as well as creativity, adaptability, empathy, and other habits that determine how one works, particularly with others [31]. Conversely, university faculty should be educated in the successful management of diverse communication styles to enable them to communicate with trainees from a wide variety of backgrounds.

The success of diversity programs will undoubtedly require significant time and effort, particularly when there is a need to find funding. As such, it will be crucial for institutions to recognize the efforts of faculty who become actively involved in diversity initiatives, in terms of promotion criteria, monetary compensation, and leadership opportunities.

How to Support Current URM STEM Members

This breakout session focused on how to seek feasible solutions to issues URMs may encounter in their daily lives. The first point of discussion focused on prejudices and approaches for ensuring that formal evaluations of URMs are less biased. People are frequently measured against previously held biased opinions. An example is the harmful stereotype of a non-smiling black woman as angry, unapproachable, and intimidating [32]. Strong and confident women can be incorrectly viewed as unreachable and domineering, leading to their wrongful exclusion from career development opportunities. A possible solution proposed by the panel was to replace subjective evaluations by objective and measurable evaluation criteria, such as the number of publications, impact factors, and grants, rather than “popularity scores,” which favor office politics and cliques of majority members over productivity.

The second point of discussion focused on approaches for helping URMs feel supported in the work environment and features that URM members should seek when pursuing a job. Networking with peers and leaders at other institutions is an important tool to find allies and prepare for the next move. Examples of networking include meeting with others virtually in a one-on-one setting, visiting an institution in-person before starting a new position, identifying diversity programs, asking about onsite URM support groups, and talking with URMs already in the department to learn about the work environment.

The third point focused on how one can be an ally to URMs and women and limit microaggressions (discussed in more detail in sect. “How to Address Microaggressions in STEM”). In this context, an ally is an individual who is not a URM or a woman but acts to support them. Daily microaggressions can significantly impact the experience and motivation of URM or women STEM members. Examples include men receiving credit for women's ideas, inappropriate comments at work, and URM team members being relegated to mundane tasks. The emotional costs of these experiences are significant, and “emotional energy” unrelated to job responsibilities is required to face these problems. Participants suggested peer mentoring as a valuable way to provide inspiration and endorsement, either as a one-on-one experience or within a group, which often provides support as well as knowledge and skills transfer. Faculty mentors should listen and be approachable, acting as a connector and sponsor. It is crucial that underrepresented members and their allies call out inappropriate behaviors and not be afraid of uncomfortable situations. In most cases, the marginalized member feels uncomfortable. If the minority becomes the majority, then an inappropriate comment or action will make the perpetrator uncomfortable.

How to Generate Pipeline Programs for URM Diversity in STEM

Increasing diversity in STEM requires an increased representation of URMs. Barriers to entry into this pipeline and program dropout are both challenges to supporting the careers of those who are underrepresented in STEM. The panel recognized that early intervention at the precollege (K-12) and college levels is critical for engaging URM students into STEM. Strategies to successfully manage early-stage pipeline programs can be applied at an individual level, such as mentorship, career advice, and research opportunities, or in the form of career development programs, such as the American College of Radiology Pipeline Initiative for the Enrichment of Radiology [33].

Obstacles to individual interventions include limited network reachability. Current networking strategies are primarily based on in-person or local interactions, which may not be efficient for talented URM students in economically disadvantaged or remote settings. Another issue is the limited bandwidth of university faculty to serve as career mentors for URM students outside their institution. Most faculty are already overcommitted in mentoring students at their institution. URM faculty in STEM sometimes take on disproportionate mentoring responsibilities relative to their peers, an activity that requires great effort but receives little recognition in terms of academic promotion and success metrics. Many session participants had experience either as contributors to or designers of larger-scale pipeline programs at their department or university. Barriers to the success of such programs included the significant effort required to design and successfully implement tailored activities for students at different levels of training. The time needed to design an intervention, engage or mentor students, and supervise research activities, as well as a lack of funding to support program faculty and administrative staff, emerged as the most relevant issue to be addressed in the future. One session participant noted that retired professionals may be interested in helping to close this gap and that their breadth of experience could be particularly helpful for trainees. Thus, active measures should be taken to recruit this potentially untapped resource. However, formal mentoring programs between retired university professors and trainees will likely require some form of compensation.

Finally, the panel discussed approaches for efficiently quantifying the success of ongoing diversity programs. It is difficult to quantitatively evaluate the short- and long-term effects of these programs, as the ultimate goal of increased URM representation and success in STEM and related fields takes many years to realize. Short-term feedback from participants must be combined with longer-term follow-up to assess the full impact of these interventions to continuously improve ongoing activities. However, while awaiting longer-term data, other interim metrics can indicate the success of various initiatives. Some possible metrics include the number of URM students recruited to radiology programs, comparisons of graduation rates for URM students in relation to their non-URM peers, comparisons with other institutional programs in which increased representation has been achieved, correlations between increases in URM faculty and URM trainee retention, and measurements of increased recruitment of junior and senior URM faculty. Furthermore, recent data-driven efforts to develop models for URM recruitment and retention, such as the Louis Stokes Center for Promotion of Academic Careers MODELS led by Dr. Isiah Warner [34], are integral to developing the quantitative framework needed to improve the success of diversity programs.

The Challenges Faced by Women in STEM Fields

This session focused specifically on women in STEM and was led by Dr. Iris Gibbs, Professor of Radiation Oncology at the Stanford University Medical Center and Associate Dean of MD Admissions. Dr. Gibbs has been a strong advocate for increasing diversity within STEM, and especially within the field of radiation oncology, and has published reports on this important topic [35, 36]. Dr. Gibbs explained that the overall representation of women in STEM has increased over the past two decades. However, despite these gains, women remain underrepresented in many areas of medicine and science, including radiology, especially at the more senior career levels (Fig. 2). The proportion of practicing women radiologists increased from 14 % in 1995 to 27 % in 2010 [38], and the percentage of women first authors and senior authors of publications in the field has risen from 12 to 34 % and 11 to 20 %, respectively [39]; however, the field of radiology lags behind other disciplines in female representation: as of 2015, women constituted approximately 75 % of pediatrics residents, 57 % of psychiatry residents, 85 % of obstetrics/gynecology residents, 46 % of internal medicine residents, 41 % of surgical residents, and 38 % of emergency medicine residents, but only 27 % of radiology residents [40]. Gender discrimination, sexual harassment, gender derogation, and incivility are persistent barriers for equity and career advancement and impact wellness. Dr. Gibbs discussed unique challenges faced by women, particularly women of color, in academic medicine by sharing her personal journey. Epidemiological research on the intersectionality of race and gender often employs intersectionality theory [41] or multidimensional theory [42] to interpret health outcomes across multiple social variables. However, the emerging use of a holistic identity approach to addressing health disparities appears to be a superior method [43]. Women of color are severely underrepresented in medicine (only ~4 %) and have little visibility [44]. While it is difficult to ascertain whether women of color experience greater disadvantage than either non-minority women or minority men, this is partially due to a dearth of data on this under represented group. Furthermore, minority women face the same obstacles that are common for women and also those faced by minorities [44]. This in itself makes the experiences of women of color unique. In a recent membership study of the American College of Radiology, women and minorities disproportionately reported disrespectful or unfair treatment though there were some differences in the attributions of these behaviors. For women, unfair or disrespectful treatment was reported to be due to their gender and age, by patients and families, and in terms of opportunities for career advancement; underrepresented minorities reported disrespectful and unfair treatment attributed to their race/ethnicity and in terms of opportunities for career advancement [45].

Fig. 2.

The “elephant in the room”: while women make up ~50 % of medical school applicants and graduates, they are increasingly underrepresented in senior and leadership positions. Reprinted from [37] with permission from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Dr. Miriam Bredella, Professor of Radiology at Harvard Medical School, Vice Chair of Radiology, and Director of the Center for Faculty Development, shared important insights regarding the impact of COVID-19 on the careers of women in STEM. Despite extensive work to improve gender equity in academic medicine, women continue to lag behind men in promotions and leadership positions. This inequity has intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected women who are taking on increased childcare and household responsibilities and/or the care of ailing relatives. Dr. Bredella described approaches to support women during this crisis, including capitalizing on the shift of scholarly conferences to a digital format to encourage more women to present their work and providing opportunities for women to be visiting professors at national and international institutions, such as the innovative Visiting Scholars Program at Harvard University, where they receive mentorship and engage in career development.

Pipeline Programs for Women in STEM

Despite a heavy investment in gender equality programs, there has been a subpar return with low overall attrition rates of women in STEM throughout their careers [46]. Notwithstanding ongoing efforts, women account for less than 13 % of engineers, 25 % of the STEM workforce, and 23 % of STEM professors [47–50].

Researchers have proposed multiple factors that may affect the attrition of women in STEM, such as a lack of women role models [51]. However, a more insidious and deep-rooted problem seems to be gender-based stereotypes. Among primary school children, the differences in perceived competencies in STEM are negligible [52]. Yet, as girls mature, the perceived gender differences in science acuity increase such that most girls have self-selected out of STEM careers by the time they leave high school [48, 51]. Reshma Saujani, who founded a charitable organization called “Girls Who Code,” believes that “women have been socialized to aspire to perfection and as a result are overly cautious,” resulting in a fear of failure, which dampens their questioning nature and prevents a sense of fulfillment in STEM careers [53].

Studies have shown that educators and mentors can have a profound impact on the development of girls toward STEM careers [52, 54]. These mentors can guide talented girls, particularly those in low-income areas or underrepresented groups, toward STEM fields [54]. Addressing gender-related stereotypes and expectations is important [47]. In addition, introducing young women to a wide variety of STEM options early on in their career may improve long-term career outcomes for women in STEM.

How to Increase Female Representation and Inclusion in STEM

This breakout session focused on efforts to better support women students and trainees within STEM. The session aimed to bring awareness to the challenges faced by women trainees, particularly women of color, and approaches for actively addressing issues of representation and inclusion. Moderators opened the session and encouraged participants to share their experiences and perspectives of women representation within their own fields. A summary of effective and successful strategies (e.g., resources, support groups, initiatives) that can be implemented into pipeline programs was shared with the participants and the organizing committee.

Panelists felt that women were more likely to enter STEM from non-traditional trajectories; for example, some participants reported being an artist or teachers before committing to STEM fields. Many came to medicine and biology after having previously pursued unrelated career paths. Panelists felt that this trend was at least partially related to the fact that young women are intimidated by STEM. Many misbeliefs may exist, such as the myths that STEM is very difficult, lifestyle choices are harder for women in STEM, or women brains are not fit for STEM.

Women may also have perfectionist personality traits, and as science and experimentation are imperfect, there may be a hesitation to experiment. Expectations of being a “super-mentor” and being able to help with all issues are unrealistic. Being the only woman (or woman of color) in the room can be daunting. Bias toward women professors persists in academic medicine and has the potential to adversely affect patient care.

Participants noted that, although STEM is supposed to be difficult, the lesson is to not back down and to learn along the way. Early exposure to STEM, including volunteering experience at hospitals, laboratories, and other STEM avenues, was helpful for some participants. Mentoring relationships formed during these experiences is pivotal for making positive career decisions. Establishing a mentoring and support network of a variety of mentors including professors, peers, and other advisors takes effort but is fruitful in the long run and is more beneficial than relying on a single mentor. Mentoring can be structured or non-structured, and a calendar appointment is not essential for a meaningful conversation. Women must seek to make both women and men allies. Moreover, challenges can be particularly overwhelming for women of color. Discussion participants suggested that attending historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) may enable some Black women to flourish and discover satisfying careers. However, HBCUs represent only ~3 % of US colleges and universities, which makes this an unviable proposition. Furthermore, while such a suggestion may, on its face, seem benign, it shifts the responsibility of fostering the success of Black women onto these institutions. Instead, we must carefully examine the reasons behind why “traditional” colleges and universities do not foster the same degree of success for people of color.

When part of a larger group, promoting younger women in the conversation helps boost inclusivity. Unconscious bias training should be mandatory in institutions to allow scientists to understand their biases, especially those against women and people of color.

In addition, steps must be taken at departmental and institutional levels to increase female representation. Many STEM departments recognize this need, especially at more senior and leadership levels, and have actively sought to recruit women employees. However, especially in fields such as radiology where women are drastically underrepresented, more efforts are needed. One strategy that departments can employ is to increase the visibility of current women radiologists to provide role models for those who are considering the specialty but are unsure whether they would fit in. Another way in which organizations can work toward this goal is to make concerted efforts to place women in leadership roles within the department. This approach serves the dual role of making women more visible while also giving them the opportunity to affect policy changes.

How to Address Microaggressions in STEM

Microaggressions are defined as indirect, subtle, or unintentional statements or actions of discrimination against members of a marginalized group. Although microaggressions can result from unconscious beliefs linked to systemic racism, they sometimes arise from a lack of knowledge on the topic or a lack of awareness. Concerted efforts are needed to correct microaggressions when they happen. One possible way of responding to microaggressions is by asking for clarification and further information regarding the statement and providing feedback about why a specific comment or action is hurtful (Fig. 3). However, this is often easier said than done. A URM individual may feel uncomfortable with directly addressing a microaggression for a myriad of reasons, not least of which is the worry that their colleagues may view them as being “hypersensitive” or “not likeable.” Furthermore, a URM individual is often the only one in a situation who recognizes a microaggression; thus, by calling out the microaggression, the URM individual risks being labeled as an “other,” which is the opposite outcome that initiatives aimed at reducing microaggressions attempt to achieve. Because they are not targeted, allies can be in a better position to address microaggressions. Allies must educate themselves on the various forms of microaggressions, so they can immediately challenge them. When allies address microaggressions, they directly validate the target and provide feedback to the perpetrator.

Fig. 3.

Addressing microaggressions and interrupting bias, used with permission from [55].

A majority of participants of this discussion group agreed that microaggressions should be addressed immediately, although not all participants felt that they would have the courage to do so. Participants shared that microaggressions made them feel different from others, upset, and angry. Some participants felt that they had become numb to microaggressions and thus did not try to respond to microaggressions even when they recognized and were negatively affected by them. In addition, participants reported that they had been previously labeled as overly sensitive when responding to microaggressions and had been attacked when questioning microaggressions. Direct feedback to intentional microaggressions would likely not change the future behavior of an individual, which may require more formal disciplinary actions, while unintentional microaggressions can be addressed more directly.

All participants agreed that group discussions on microaggressions are helpful, that the issue should be discussed more often, and that it is essential to increase awareness about microaggressions and learn more about strategies for dealing with them. Participants, consisting of women only, also noted that it is important to increase the gender distribution of those involved in such group discussions.

Global Health

To start the discussion, Dr. Justin Tse provided an overview of his experience as a visiting Radiology resident at the Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The MNH serves as a tertiary referral center for a country of over 55 million people. Eight staff radiologists provide medical-imaging-related services for this 1600-bed hospital. Radiology as an independent department is relatively new at MNH, and the residency program is only 10 years old. The hospital has modern radiology equipment, highly motivated residents and staff, a wide referral base, and a large patient population with complex pathologies, including neurology, cardiology, oncology, and surgery. In this lecture, Dr. Tze shared lessons learned, including [1] the role of radiologists in promoting healthcare access in developing countries, [2] common misconceptions about global health radiology, [3] ways to contribute and maximize impact, and [4] strategies to maintain sustained growth.

Dr. Yuri Quintana described approaches to increasing the impact of medical research and treatments for global populations. Curricula must integrate global health, specifically by linking cultural competence with global health in medical education [56, 57]. Furthermore, there is a lack of diversity in the populations studied in clinical trials [10–12], which limits their applicability to underrepresented groups. Thus, we need more global collaborations that focus on capacity building in clinical care and research [58]. One example is the Men of African Descent and Carcinoma of the Prostate Consortium, which is collaborating on epidemiologic studies to address the high burden of prostate cancer among this historically underserved population. These investigators aim to understand the complex multifactorial causes of prostate cancer etiology and outcomes among men of African ancestry worldwide [58].

Dr. Michele Barry discussed women leadership in the context of global health. Attention in global health is often focused on financing, the distribution of commodities, and the development of innovative tools, with little focus on the people responsible for ensuring that these resources reach everyone who needs them. Despite accounting for over 70 % of the global health workforce, fewer than 20 % of individuals in leadership positions identify as female. Hence, we need to improve gender diversity in our teams [59, 60]. The lowest percentage of female representation within the American Association of Physicists in Medicine is among council chairs, with only one woman having held a chair position out of 42 positions (2.4 %) from 1970 to July 2019 [60]. In a report [61] that sampled 200 global health organizations, more than 70 % of the leaders were men, more than 80 % were nationals of high-income countries (HICs), and more than 90 % were educated in HICs. Norway increased the percentage of women on boards through concerted efforts [62], by introducing quotas in 2003 mandating that publicly listed corporations reserve a minimum of 40 % of board seats for women. Companies were given until 2008 to achieve compliance. In 2003, the year the quota was adopted, ~20 % of individuals on Norwegian company boards were women; by 2005, this proportion was 35 % (compared with 19 % in the USA and 3 % in Japan), and in 2009, this value exceeded 40 % [63]. Research has shown that a greater proportion of women in leadership correlates with increased public health spending [64] and greater public confidence in the government [65].

Multidisciplinary approaches to global problems, rather than siloed solutions that are not inclusive or sustainable, must be fostered. Some recommendations for the future include [1] placing global health research on an equal footing with domestic health research (funding, career advancement); [2] achieving diversity in research teams, in target population studies, and in funders (board members); [3] improving the diversity of funding priorities focused on the needs of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); [4] investing in sustainable training of people and infrastructure in LMICs and modifying solutions for LMICs; and [5] creating long-term partnerships between institutions and creating Global Communities of Research and Practice to sustain projects and relationships.

How “Global” Is Global Health?

In a world that is continuously becoming more connected, increased general awareness and feelings of responsibility toward health disparities worldwide have driven a global health movement. Koplan et al. were the first to delineate the span of global health as “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide” [66]. Of note, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has unquestionably reminded us that developed countries are not immune to deadly infections and that global health coordination is essential to reduce worldwide mortality and economic impacts.

Global health is usually characterized by health outcomes, such as life expectancy, child mortality, and infectious diseases. The panel discussed a few World Health Organization charts depicting global health disparities in these areas and concluded that numerous challenges remain, falling into three main categories: data, research, and policy.

Panelists emphasized the importance of data gathering and transparency (especially for sensitive topics such as suicide and mental health) and the need for quantitative tools to measure the impact of specific policies on the data.

Participants also suggested enhancing the diversity of research subjects (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.) in clinical studies. Moreover, panelists discussed the need to level the field for disease funding to solve global health problems, for example, by directing more funds toward preventable or curable diseases in developing countries. The group discussed whether the idea of a centralized global agency that would coordinate and distribute medical research funding equitably corresponds to a utopia and whether global health disparity is simply a money issue. The panelists emphasized that, beyond monetary help, policy implementation and global cooperation are necessary to maximize impact. Governments should promote access to public services and support particularly vulnerable groups. Policymakers, researchers, and healthcare professionals must work together but remain independent from each other to best guide decisions regarding public and global health.

The panel also discussed strategies that could be implemented at the individual, university, and national level to reduce global health disparities. At the personal level, researchers have the responsibility to report reliable data to the scientific community. At the institutional level, universities can implement visiting scholar programs, specifically those with the goal of knowledge transfer, to yield a broad impact in developing nations. The panel also discussed encouraging universities to diversify their portfolio beyond cancer, heart disease, and dementia research, to focus on additional areas that affect global health. For example, neglected tropical diseases primarily affect low-income and developing countries [67]; however, research for these diseases receives little funding compared with other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria, despite a similar health impact within developing countries [68, 69]. The current pandemic has reinforced the rationale for such pursuits. Rebalancing disease research disparities is a critical step toward equity in health.

The panel concluded that effectively addressing global health issues relies on promoting access to data, increasing research means, and implementing policy changes at the national level and as a global partnership.

How to Advance Global Health Research

Global health research focuses on the health of people living in LMICs and on understanding systematic factors that shape health are inherently global. Established researchers in developed countries can support researchers in developing countries through training and mentoring. However, research methods in developed countries may require adaptation depending on the infrastructure and resources of a low-income country. For example, diseases that may be interrogated with cross-sectional imaging studies in HICs may be approached with different imaging modalities, or often not at all, in low-income countries. The panel identified the need to expand medical centers and universities in developing countries to provide meaningful medical care for patients and career opportunities for early-career researchers to mitigate the “brain drain.”

The panel discussed the use of technology to address limited resources and the need for skills transfer to implement and adapt technologies for local healthcare systems. Telemedicine and artificial intelligence (AI) are good examples of technologies that can be employed to reduce the burden on limited resource systems. AI may be helpful, with the potential to make a difference in several narrow applications (e.g., aiding radiograph interpretation). To facilitate this approach, adaptation to local circumstances is needed. Dr. Quintana described Alicanto (Fig. 4), a platform and online community that could enable online skills transfer for both clinical care and research in developing countries [70].

Fig. 4.

Alicanto is a platform and online community that could enable online skills transfer for both clinical care and research in developing countries.

While there is much excitement about AI applications for clinical care in developing countries, there is no successful example related to medical imaging to date. The panel discussed problems with AI bias in algorithms and the need for further research prior to the use of algorithms developed in high-income populations for other populations with different clinical, genetic, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Cultural Competence in Global Health

Cultural competence describes the ability to understand, communicate with, and effectively interact with people across cultures [71]. The panel emphasized that cultural competence is a matter of intellectual flexibility. Cultural competence is not only the recognition that different cultures exist but also a fundamental acceptance of different styles and viewpoints [72–74]. Cultural competency has become increasingly important to meet the needs of diverse patient populations.

The panel discussed the benefits of cultural competence in the clinical setting. A review of culturally competent healthcare practices and outcomes [75, 76] illustrated the positive impact of language competence [77–80] and the inclusion of culture-specific concepts [81–83]. Culturally competent healthcare reduces health disparities, medical errors, medical visits, and enhances preventative care. Moreover, the added social benefits include increased trust and community member inclusion. All of these factors lead to improved outcomes for patients and increased provider satisfaction and morale.

To improve cultural competency, the panel felt that more substantive cultural competence education and integration as a standardized part of the medical curriculum would provide a good start. Other suggestions included using an interdisciplinary approach to address the synergy between cultural competence and global health and embedding the topic throughout the curriculum. Furthermore, given the dynamics of culture, more concerted efforts should be made to provide continuing education in cultural competence [84].

Summary

It is widely accepted that gender and racial diversity benefit both organizations (improved morale [85] and motivation [86]) and fields/specialties (improved decision-making [87, 88] and results [89, 90]). However, many current efforts aimed at eliminating discrimination and increasing diversity focus primarily on training. While training initiatives yield success [91], there is a risk that these efforts will lead to “box ticking” as opposed to real change. If not reinforced, the initial success of DEI training can be lost. Conversely, repeated training sessions (e.g., annual training) can be less productive if the training becomes a repetitive course (i.e., same content presented every year) that people feel they need to “get through.” When designing ongoing diversity training/initiatives, organizers should seek new and innovative ways to present material and ideas to their audience. Diversity events and activities, such as the one summarized in this review, are an integral component to shaping attitudes and enhancing gender, racial, and cultural diversity [92]. Continuing education in diversity through themed programs and activities, as opposed to annual “trainings,” offers the opportunity to positively engage participants and find solutions for emerging issues related to diversity.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 1832 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Lisa Baird, CEO of the WMIS, Lauren Whitman, and Sylvia Anderson from the WMIS, Mekemeke Faooso and Tricia Hatcliff from Stanford Radiology, and Emily Manche from the Stanford CME office, who organized all administrative aspects of the event. We would also like to thank members of the WMIS and Stanford Radiology leadership team, who provided opening remarks on each of the conference days, including Dr. Martin Pomper, immediate past president of the WMIS, Dr. Garry Gold, Interim Chair of the Radiology Department at Stanford, Dr. Carolyn Anderson, President Elect of the upcoming WMIS, Dr. Jason Lewis, Editor in Chief of Molecular Imaging & Biology, and Dr. Payam Massaband, Program Director of the Stanford Radiology Residency Program. Many thanks also to the 32 moderators from 15 different institutions, who facilitated the presentations and breakout sessions! We are grateful to our invited speakers, including Dr. Kassa Darge, MD, PhD, DTM&P, FSAR, FESUR, Chair of the Department of Radiology at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Dr. Iris Gibbs, MD, FACR, FASTRO, Associate Dean of MD Admissions, Stanford Medicine, Dr. Miriam Bredella, MD, Vice Chair, Department of Radiology and Director of the Center of Faculty Development, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard, Dr. Michele Barry, MD, FACP, Senior Associate Dean of Global Health at Stanford, Dr. Yuri Qintana, PhD, Director of Global Health Informatics at BIDC, Harvard, Dr. Brielle Ferguson, PhD, NRSA Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford, Dr. Jayne Seekins, DO, faculty leader of the Radiology outreach program, and Dr. Justin Tse, MD, Stanford Radiology resident. We thank Dr. Julie Gosse for editing this manuscript. A big thanks to all contributors and attendees for investing the time and effort to share their experiences with us!

Funding

The authors have no sources of funding to disclose. Dr. Iris C. Gibbs, MD, declares receiving honoraria for lectures unrelated to the current subject matter (Accuray, Inc.).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Summary Report of the September 9–11, 2020 Virtual Diversity in Radiology and Molecular Imaging Conference

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dennehy TC, Dasgupta N. Female peer mentors early in college increase women's positive academic experiences and retention in engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:5964–5969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613117114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurtado S, Newman CB, Tran MC, Chang MJ. Improving the rate of success for underrepresented racial minorities in stem fields: insights from a national project. New Dir Inst Res. 2010;2010:5–15. doi: 10.1002/ir.357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan DL. Perceived importance of role models and its relation- ship with minority student satisfaction and academic performance. NACADA Journal. 1995;15:48–51. doi: 10.12930/0271-9517-15.1.48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vecci J, Zelinsky T. Behavioural challenges of minorities: social identity and role models. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman CH, Hwang WT, Both S, Thomas CR, Jr, Deville C. Current status of diversity by race, Hispanic ethnicity, and sex in diagnostic radiology. Radiology. 2014;270:232–240. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2011;306:1015–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2010;304:1255–1270. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2008-2009. JAMA. 2009;302:1357–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2008;300:1228–1243. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bentley AR, Callier S, Rotimi CN. Diversity and inclusion in genomic research: why the uneven progress? J Community Genet. 2017;8:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s12687-017-0316-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hindorff LA, Bonham VL, Brody LC, Ginoza MEC, Hutter CM, Manolio TA, Green ED. Prioritizing diversity in human genomics research. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:175–185. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentley AR, Callier SL, Rotimi CN. Evaluating the promise of inclusion of African ancestry populations in genomics. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:5. doi: 10.1038/s41525-019-0111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter-Edwards L, Fisher JT, Vaughn BJ, Svetkey LP. Church rosters: is this a viable mechanism for effectively recruiting African Americans for a community-based survey? Ethn Health. 2002;7:41–55. doi: 10.1080/13557850220146984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span study. Gerontologist. 2011;51(Suppl 1):S33–S45. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, Tilburt J, Baffi C, Tanpitukpongse TP, Wilson RF, Powe NR, Bass EB. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuman SH, Olansky S, Rivers E, Smith CA, Rambo DS. Untreated syphilis in the male negro; background and current status of patients in the Tuskegee study. J Chronic Dis. 1955;2:543–558. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(55)90153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reverby SM. Will the STI studies in Guatemala be remembered, and for what? Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:301–302. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattson ME, Curb JD, McArdle R. Participation in a clinical trial: the patients' point of view. Control Clin Trials. 1985;6:156–167. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(85)90121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:90–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1363–1369. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Medical Education. 2015;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norbash A, Kadom N. The business case for diversity and inclusion. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrovsky, A. & Barnett, M. (n.d.) in Healthcare. 9-13 (Elsevier).

- 26.Andrews R, Greasley S, Knight S, Sireau S, Jordan A, Bell A, White P. Collaboration for clinical innovation: a nursing and engineering alliance for better patient care. J Res Nurs. 2020;25:291–304. doi: 10.1177/1744987120918263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardeman AN, Kahn MJ. Technological innovation in healthcare: disrupting old systems to create more value for African American patients in academic medical centers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarver WL, Haggstrom DA. The use of cancer-specific patient-centered technologies among underserved populations in the United States: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e10256. doi: 10.2196/10256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zambrana RE, Ray R, Espino MM, Castro C, Douthirt Cohen B, Eliason J. “Don’t leave us behind”: the importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. Am Educ Res J. 2015;52:40–72. doi: 10.3102/0002831214563063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jagannathan R, Camasso J. M. & MaiaDelacalle. Promoting cognitive and soft skills acquisition in a disadvantaged public school system: evidence from the Nurture thru Nature randomized experiment. Econ Educ Rev. 2019;70:173–191. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soft Skills: Definitions and Examples (2020). https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/soft-skills.

- 32.Kilgore AM, Kraus R, Littleford LN. “But I'm not allowed to be mad”: how Black women cope with gendered racial microaggressions through writing. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2020;6:372–382. doi: 10.1037/tps0000259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.PIER Internship (2020). https://www.acr.org/Member-Resources/Medical-Student/Medical-Educator-Hub/PIER-Internship.

- 34.Louis Stokes Center for the Promotion of Academic Careers Through Motivational Opportunities to Develop Emerging Leaders in STEM (LS-PAC-MODELS), (2021). https://www.lsu.edu/osi/ls-pac/index.php.

- 35.Deville C, Jr, Cruickshank I, Jr, Chapman CH, Hwang WT, Wyse R, Ahmed AA, Winkfield KM, Thomas CR, Jr, Gibbs IC. I can't breathe: the continued disproportionate exclusion of black physicians in the United States radiation oncology workforce. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapman CH, Gabeau D, Pinnix CC, Deville C, Jr, Gibbs IC, Winkfield KM. Why racial justice matters in radiation oncology. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020;5:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colleges, AOAM (2020) The state of women in academic medicine 2018-2019: exploring pathways to equity.

- 38.Liang T, Zhang C, Khara RM, Harris AC. Assessing the gap in female authorship in radiology: trends over the past two decades. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pyatigorskaya N, Di Marco L. Women authorship in radiology research in France: an analysis of the last three decades. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2017;98:769–773. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AMA (2015). https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/specialty-profiles/how-medical-specialties-vary-gender.

- 41.Crenshaw, K (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legals Forum.

- 42.AL, R. & RL, P. The complexities of diversity: exploring multiple oppression. Journal of Couseling and Development. 1991;70:174–180. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1991.tb01580.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bey, G (2020) Health disparities at the intersection of gender and race: beyond intersectionality theory in epidemiologic research.

- 44.Wong EY, Bigby J, Kleinpeter M, Mitchell J, Camacho D, Dan A, Sarto G. Promoting the advancement of minority women faculty in academic medicine: the National Centers of Excellence in Women's Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:541–550. doi: 10.1089/15246090152543120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandharipande PV, Mercaldo ND, Lietz AP, Seguin CL, Neal CD, Deville C, Parikh JR, Sadigh G, Sepulveda KA, Maturen KE, Cox J, Bansal S, Macura KJ, Donelan K. Identifying Barriers to building a diverse physician workforce: a national survey of the ACR membership. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang DF, ChangTzeng HC. Patterns of gender parity in the humanities and STEM programs: the trajectory under the expanded higher education system. Stud High Educ. 2020;45:1108–1120. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1550479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sassler S, Glass J, Levitte Y, Michelmore KM. The missing women in STEM? Assessing gender differentials in the factors associated with transition to first jobs. Soc Sci Res. 2017;63:192–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghasemi, E. & Burley, H. (2019) Gender, affect, and math: a cross-national meta-analysis of Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study 2015 outcomes. Large-Scale Assess E 7, 10.1186/s40536-019-0078-1.

- 49.Science, AAO (2019). https://www.science.org.au/support/analysis/decadal-plans-science/women-in-stem-decadal-plan.

- 50.Ellis, J., Fosdick, B. K. & Rasmussen, C. Women 1.5 times more likely to leave STEM pipeline after calculus compared to men: lack of mathematical confidence a potential culprit. PLoS One 11, e0157447, 10.1371/journal.pone.0157447 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Weeden KA, Gelbgiser D, Morgan SL. Pipeline dreams: occupational plans and gender differences in STEM major persistence and completion. Sociol Educ. 2020;93:297–314. doi: 10.1177/0038040720928484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Hurk A, Meelissen M, van Langen A. Interventions in education to prevent STEM pipeline leakage. Int J Sci Educ. 2019;41:150–164. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2018.1540897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saujani, R (2019) Brave not perfect: fear less, fail more and live bolder. Vol. 1 Currency.

- 54.Boelter C, Link TC, Perry BL, Leukefeld C. Diversifying the STEM pipeline. J Educ Stud Placed Risk. 2015;20:218–237. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2015.1030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haslam, R. E. (2019) Interrupting Bias: Calling Out vs. Calling In.

- 56.Eaton DM, Redmond A, Bax N. Training healthcare professionals for the future: internationalism and effective inclusion of global health training. Med Teach. 2011;33:562–569. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.578470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mews C, et al. Cultural competence and global health: perspectives for medical education - position paper of the GMA Committee on Cultural Competence and Global Health. GMS J Med Educ. 2018;35:Doc28. doi: 10.3205/zma001174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lightfoote JB, Fielding JR, Deville C, Gunderman RB, Morgan GN, Pandharipande PV, Duerinckx AJ, Wynn RB, Macura KJ. Improving diversity, inclusion, and representation in radiology and radiation oncology part 2: challenges and recommendations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Battaglia F, Shah S, Jalal S, Khurshid K, Verma N, Nicolaou S, Reddy S, John S, Khosa F. Gender disparity in academic emergency radiology. Emerg Radiol. 2019;26:21–28. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Covington EL, Moran JM, Paradis KC. The state of gender diversity in medical physics. Med Phys. 2020;47:2038–2043. doi: 10.1002/mp.14035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.https://globalhealth5050.org/2020report/. (2020) Global Health 50/50.

- 62.https://theconversation.com/lessons-from-norway-in-getting-women-onto-corporate-boards-38338. Lessons from Norway in getting women onto corporate boards, (2015).

- 63.https://www.economist.com/business/2018/02/17/ten-years-on-from-norways-quota-for-women-on-corporate-boards. Ten years on from Norway’s quota for women on corporate boards, (2018).

- 64.Mavisakalyan A. Women in cabinet and public health spending: evidence across countries. Economics of Governance We. 2014;15:281–304. doi: 10.1007/s10101-014-0141-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clayton, A., O'Brien, D. Z. & Piscopo, J. M. (2018). All male panels? Representation and democratic Legitimacy. American Journal of Political Science.

- 66.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, Wasserheit JN. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373:1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hotez PJ, Aksoy S, Brindley PJ, Kamhawi S. What constitutes a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hotez PJ, Kamath A. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-saharan Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hotez PJ, NTDS V. 2.0: "blue marble health"--neglected tropical disease control and elimination in a shifting health policy landscape. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henao J, Quintana Y, Safran C. Alicanto online Latin American maternal informatics community of practice. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;264:1676–1677. doi: 10.3233/SHTI190592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garrido R, Garcia-Ramirez M, Balcazar EF. Moving towards community cultural competence. Int J Intercult Relat. 2019;73:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar R, Bhattacharya S, Sharma N, Thiyagarajan A. Cultural competence in family practice and primary care setting. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_393_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blanchet Garneau A, Pepin J. Cultural competence: a constructivist definition. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26:9–15. doi: 10.1177/1043659614541294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Handtke O, Schilgen B, Mosko M. Culturally competent healthcare - a scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0219971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Renzaho AM, Romios P, Crock C, Sonderlund AL. The effectiveness of cultural competence programs in ethnic minority patient-centered health care--a systematic review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:261–269. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mehler PS, Lundgren RA, Pines I, Doll K. A community study of language concordance in Russian patients with diabetes. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goncalves M, Cook B, Mulvaney-Day N, Alegria M, Kinrys G. Retention in mental health care of Portuguese-speaking patients. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50:92–107. doi: 10.1177/1363461512474622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ortega AN, Rosenheck R. Hispanic client-case manager matching: differences in outcomes and service use in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:315–323. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trinh NH, et al. Evaluating patient accepaility of a culturally focused psychiatric consultation intervention for Latino Americans with depression. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:1271–1277. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.La Roche MJ, Batista C, D'Angelo E. A culturally competent relaxation intervention for Latino/as: assessing a culturally specific match model. Am J Orthop. 2011;81:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aviera A. "Dichos" therapy group: a therapeutic use of Spanish language proverbs with hospitalized Spanish-speaking psychiatric patients. Cult Divers Ment Health. 1996;2:73–87. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.2.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yasui M, Henry DB. Shared understanding as a gateway for treatment engagement: a preliminary study examining the effectiveness of the culturally enhanced video feedback engagement intervention. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:658–672. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sania, U, Kalpina, K, Javed, H (2015) Diversity, Employee Morale and Customer Satisfaction: The Three Musketeers. Journal of Economics, Business and Management 3.

- 86.Velten, L ,Lashley, C (2018). The meaning of cultural diversity among staff as it pertains to employee motivation. Research in Hospitality Management 7.

- 87.Webber SS, Donahue LM. Impact of highly and less job-related diversity on work group cohesion and performance: a meta-analysis. J Manag. 2001;27:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jackson, SE, Joshi, A, Erhardt, NL (2003). Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management 29.

- 89.Herring C. Does Diversity Pay?: Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. Am Sociol Rev. 2009;74:208–224. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kalinoski ZT, Steele-Johnson D, Peyton EJ, Leas KA, Steinke J, Bowling NA. A meta-analytic evaluation of diversity training outcomes. J Organ Behav. 2013;34:1076–1104. doi: 10.1002/job.1839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Robinson AN, Arena DF. P., L. A. & Ruggs, E. N. Expanding how we think about diversity training. Ind Organ Psychol. 2020;13:236–241. doi: 10.1017/iop.2020.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1832 kb)