Precipitation of heart failure (HF) has been described in the setting of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) (1), yet population-based studies are needed to provide a context within which the frequency of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV2)–related HF can be appreciated (2,3). Our objective was to describe the point-prevalence and associated outcomes of new HF diagnoses among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients admitted with a positive polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV2 to Mount Sinai hospitals in New York between February 27, 2020, and June 26, 2020, and followed until October 7, 2020. Clinical characteristics and outcomes (need for intensive care unit [ICU], intubation, in-hospital mortality) were captured from electronic health records. History or new diagnosis of HF was identified by International Classification of Diseases-9th/-10th Revision codes and confirmed by manual chart review. New HF diagnoses were established by ensuring no prior history of HF, and fulfillment of 2 of the 3 following criteria (4): 1) signs and symptoms of congestion; 2) elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels (BNP >100 pg/ml or N-terminal pro-BNP >300 pg/ml); and 3) x-ray findings compatible with HF (cardiomegaly and/or congestion) or echocardiographic evidence of diastolic/systolic dysfunction. The Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board approved this research. Variables were compared between patients with and without HF as well as between those with cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) or cardiovascular disease (CVD) (atrial fibrillation, stroke, coronary artery disease) by using the Fisher exact or chi-square test for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test, analysis of variance, Wilcoxon, or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Because only in-hospital mortality was assessed, discharge was treated as a competing outcome for survival analysis. Cumulative incidence of ICU care, intubation, and in-hospital mortality were compared between patients with new HF versus without by Fine and Gray’s method, reported by subdistribution hazard ratios (sHRs).

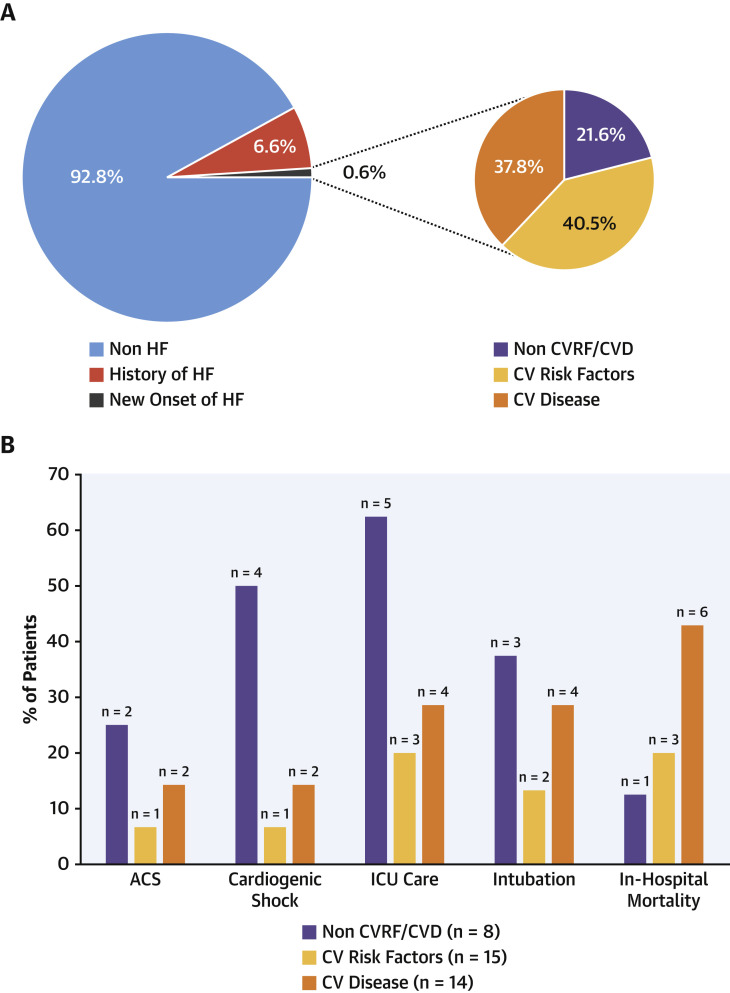

Of 6,439 patients, 37 (0.6%) had new HF and 422 (6.6%) had a history of HF (Figure 1A ). The mean age was 64 years, and 45% were women. Outcomes for patients with prior HF have been reported previously (5). Of 37 new HF patients, 13 presented with shock (4 cardiogenic, 6 septic, 3 mixed), and 5 presented with acute coronary syndrome. Remarkably, 8 patients (22%) had neither CVRF nor CVD, while 14 (38%) had a history of CVD, and 15 (40%) had at least 1 CVRF. The aforementioned 8 patients were younger, were mostly men, had lower body mass, and had fewer comorbidities compared with other new HF patients. Significant ST-segment deviation (1 regional and 4 diffuse) was observed on 5 of 37 admission electrocardiograms. Echocardiography was performed in 28 (76%) patients; most (n = 22) showed left ventricular ejection fraction <50%, while 6 met criteria for diastolic dysfunction. Compared with patients without HF, new HF patients experienced increased risk of ICU (32% vs. 17%; sHR: 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2 to 3.8) and intubation (24% vs. 12%; sHR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.2 to 4.3), but not mortality (27% vs. 25%; sHR: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.6 to 2.0).

Figure 1.

Prevalence, Clinical Profile, and Outcomes of New HF Patients With COVID-19

(A) Point-prevalence and clinical profile of new HF in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. (B) Outcomes according to the presence of CVRF and CVD. ACS = acute coronary syndrome; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019; CVD = cardiovascular disease; CVRF = cardiovascular risk factors; HF = heart failure; ICU = intensive care unit.

New HF patients showed both troponin concentrations (221.45 ng/ml vs. 0.03 ng/ml vs. 0.18 ng/ml) and BNP plasma levels (588 pg/ml vs. 163 pg/ml vs. 356 pg/ml) significantly higher compared with patients with CVRF and CVD disease, respectively. Despite more frequent presentation of cardiogenic shock and acute coronary syndrome, the 8 new HF patients without CVRF or CVD encountered similar length of stay (6 days [interquartile range: 4 to 27 days] vs. 8 days [interquartile range: 3 to 13 days] vs. 7 days [interquartile range: 3 to 11 days]; p = 0.947), but had more frequent ICU requirement and intubation and lower in-hospital mortality compared with new HF patients with CVRF or CVD, respectively (Figure 1B).

As viral illnesses such as influenza have been reported to precipitate new HF, similar speculative correlations have been drawn with COVID-19. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to date to provide a context for reports of new-onset HF in the setting of hospitalization for SARS-CoV2 infection. We demonstrate that, although the point prevalence of new HF is low, a distinct cohort of younger patients without cardiovascular risk factors or disease experience new HF that may indeed be related to COVID-19. The majority of new HF patients, however, had either CVRF or overt CVD (stages A to B HF). Understanding specific mechanisms underlying the manifestation of COVID-19 as new HF warrants further study.

Footnotes

Dr. Alvarez-Garcia has received a mobility grant from Private Foundation Daniel Bravo Andreu. Dr. Rivas-Lasarte has received a “Magda Heras” mobility grant from the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Dr. Lala has received personal fees from Zoll, outside of the submitted work. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Gonzalo Alonso Salinas, MD, PhD, served as Guest Associate Editor for this paper. Athena Poppas, MD, PhD, served as Guest Editor-in-Chief for this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Pinney S.P., Giustino G., Halperin J.L. Coronavirus Historical Perspective, Disease Mechanisms, and Clinical Outcomes: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1999–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rey J.R., Caro-Codón J., Rosillo S.O. Heart failure in COVID-19 patients: prevalence, incidence and prognostic implications. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:2205–2215. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomasoni D., Inciardi R.M., Lombardi C.M. Impact of heart failure on the clinical course and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Results of the Cardio-COVID-Italy multicentre study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:2238–2247. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Garcia J., Lee S., Gupta A. Prognostic impact of prior heart failure in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2334–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]