Abstract

Bifidobacterium has a diverse host range and shows several beneficial properties to the hosts. Many species should have co-evolved with their hosts, but the phylogeny of Bifidobacterium is dissimilar to that of host animals. The discrepancy could be linked to the niche-specific evolution due to hosts’ dietary carbohydrates. We investigated the relationship between bifidobacteria and their host diet using a comparative genomics approach. Since carbohydrates are the main class of nutrients for bifidobacterial growth, we examined the distribution of carbohydrate-active enzymes, in particular glycoside hydrolases (GHs) that metabolize unique oligosaccharides. When bifidobacterial species are classified by their distribution of GH genes, five groups arose according to their hosts’ feeding behavior. The distribution of GH genes was only weakly associated with the phylogeny of the host animals or with genomic features such as genome size. Thus, the hosts’ dietary pattern is the key determinant of the distribution and evolution of GH genes.

Keywords: Bifidobacterium, evolution, glycoside hydrolase, phylogenetics, comparative genomics

1. Introduction

Commensal gut bacteria are environment-specific and evolve together with their hosts. The genus Bifidobacterium is a widespread and abundant genus belonging to phylum Actinobacteria and is mainly distributed in the intestinal environments of various animals, from insects to mammals [1,2,3,4,5,6]. They have been considered beneficial microorganism to host health. With respect to humans, they are the first colonizers of gut microbiota; a vertical transmission from mother to offspring in humans but also in other animals plays a fundamental role in bifidobacterial occurrence in the gut microbiota. Moreover, colonization of bifidobacteria is modulated by “indigestible” carbohydrates, such as oligosaccharides derived from breastmilk in mammals and plants. These compounds together with the physiology of the host are important drivers of bifidobacterial host co-evolution. It has been shown that certain bifidobacterial species are both host- and niche-specific. Examples of host-specific species are Bifidobacterium breve for humans, Bifidobacterium rousetti for bat and Bifidobacterium reuteri for marmoset [7,8]. On the other hand, there are some species with cosmopolitan lifestyle such as Bifidobacterium longum, isolated from humans and animals, and Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, isolated from different animal species. Since whole genomes are available for many Bifidobacterium strains belonging to different species, several genome-scale analyses revealed the acquisition of specific genes, allowing their host specificity [9].

The genomic reservoir of the genus shows an open pan-genome, harboring a large number of strain-specific genes. The genome composition of host-specific strains shows weak association with the phylogeny of their host animals, especially in terms of accessory genes for amino acid production and carbohydrate degradation [10]. Notably, bee-derived species cluster themselves in a deep branch with small genome sizes [11]. Despite multiple attempts, however, identification of host specificity and elucidation of its mechanism has remained unclear from the whole genome analyses.

In this study, we focus on the relationship between host diets and bacterial glycoside hydrolases (GHs) to investigate the evolutionary relationship between bifidobacteria and host animals. To identify this relationship, bifidobacterial species were classified into 13 different groups based on their host dietary patterns. A comparative analysis approach was used to inspect the genomic features such as genome size and GH gene content among the dietary groups. The phylogenetic relationship among the species was also assessed and the phylogenetic signal for the GH content was calculated. Our comparative analysis provides insight into bifidobacterial adaptation to ecological niches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genomic Data and Annotations

For the genus-level classification, the type strain data of the 84 recognized Bifidobacterium taxa with 76 species and 8 subspecies (Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, B. longum subsp. infantis, B. longum subsp. suis, Bifidobacterium catenulatum subsp. kashiwanohense, B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum, Bifidobacterium pullorum subsp. gallinarum, B. pullorum subsp. saeculare, Bifidobacterium thermacidophilum subsp. thermacidophilum) were used (Supplementary Table S1). For the multi-host analysis, 66 strains from hosts with varying feeding behavior were used (Supplementary Table S2). For the analysis on B. animalis subsp. lactis, 45 strains were used (Supplementary Table S3).

Genomic sequences were collected from the NCBI Assembly Database and annotated by the DFAST stand-alone software program [12]. Cluster of Orthologous Group (COG) functional annotations were assigned by performing the Reverse Position-Specific BLAST against the NCBI-CDD and by the Perl script “cdd2cog” (https://github.com/aleimba/bac-genomics-scripts/tree/master/cdd2cog; accessed on 29 October 2019). The host and diet information for each strain was collected manually from the NCBI databases and related publications.

2.2. Orthologous Gene Clustering

Orthologous gene clustering was performed using the GET_HOMOLOGUES software package [13] (cutoff: E-value 1.0 × 10−5, with minimum percentage coverage of 75%) and clusters were detected by the OrthoMCL algorithm [14]. Gene clusters constituting the pan-genome and the core-genome were selected based on the trend of the COG categories. The ratios of COG classes among different set of core genomes (from 100% to 83% core) was compared and an appropriate core was chosen [15].

2.3. Identification of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes

The HMMER search against the dbCAN HMM database was used to determine carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes) [16]. The definition of GH families also follows the CAZy database. The standalone version of dbCAN annotation tool was used to determine their annotations.

2.4. Selection of the GH Families for Clustering Bifidobacterium Strains

To classify the bacterial strains with their GH distribution, the selection of the GH families is crucial. GH genes are non-essential, and only two families were shared by all the strains, GH3 and GH36 (Supplementary Table S4). On the other hand, out of 72 GH families, 24 families were present in fewer than 5 strains (<5%). To select the GH families that were moderately shared among the strains, we created GH sets that were shared by 100% of 84 taxa, >95% of the taxa, >90%, >85%, and so on (21 sets). Based on each GH set, we performed a hierarchical clustering of bacterial taxa using the distribution of corresponding GH genes and compared results. The GH set of sharing level >20% (Set 17 in Supplementary Table S4) produced the same clustering result as >15% and >10% (Set 18 and Set 19 in Supplementary Table S4), indicating that the classification using 32~42 GH families was stable. Therefore, we selected the threshold of >20% in this analysis.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

To infer the phylogenetic relationship among the type strains, the phylogenetic tree based on 362 strict-core proteins was used. The protein alignments were trimmed using trimAL (-automated 1 option) before concatenation [17], and the alignment was constructed using MAFFT version 7.313 [18]. The tree was built using RaxML version 8.27 using PROTGAMMA-BLOSUM62 substitution model and maximum likelihood method [19]. The tree was rooted with Scardovia inopinata JCM 12537T. The statistical reliability was evaluated by bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates with the Bootstrap rapid hill climbing algorithm. The tree was visualized using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/; accessed on 15 November 2019) [20].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Kruskal-Wallis test (significance level of p < 0.05) and Dunn’s post hoc test was performed using the R version 3.6.2. Phylogenetic signal for genomic trait of GH content was calculated using the R package “phylosignal” [21]. GH content is defined as the percentage of GH genes in each bifidobacterial type strain.

To measure the strength of the phylogenetic signal (likelihood of shared evolutionary history), we used Blomberg’s K statistic [22]. The K values closer to 1 and 0 indicate strong and weak evolutionary correlation, respectively. To detect the hotspots of autocorrelation, local Moran’s I for each species and local indicator of phylogenetic association (LIPA) were computed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Host Diet and the Genome Size of Type Strains

The genomic sequences for 84 Bifidobacterium type strains (76 species and 8 subspecies) were investigated. The genome size of the strains ranged from 1.63 to 3.25 Mb with an average of 2.43 Mb (SD ± 0.40). The GC content ranged from 50.4 to 66.6% with an average of 60.8%. The orthologous clustering of their coding genes revealed that the pan-genome amounted to 24,181 gene clusters including singletons.

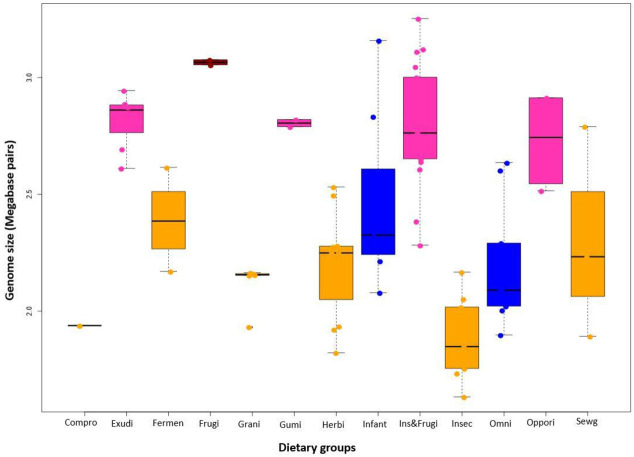

The number of clusters shared across ≥80 strains and across all strains were 722 and 362, respectively. The latter strict core was used to construct the phylogenetic tree by concatenating the amino acid sequences of the strict-core genes. In the resulting tree, 10 previously described groups [23] and one additional group were identified. The new group consisted of Bifidobacterium avesanii and Bifidobacterium vespertilionis (Figure 1). The former strain was isolated from cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus), a new-world monkey in South America feeding mainly on fruits and insects [24]. The latter, B. vespertilionis, was isolated from Egyptian fruit-bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) feeding only on the pulp and juice of various fruits [25]. Two strains, Bifidobacterium tsurumiense and Bifidobacterium minimum, were not included in any cluster.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on concatenated amino acid sequences of 362 core genes of the 84 type strains. Bootstrap percentages of >70 are shown. Eleven phylogenetic groups are highlighted in different colors and the new group is the second rightmost (rose).

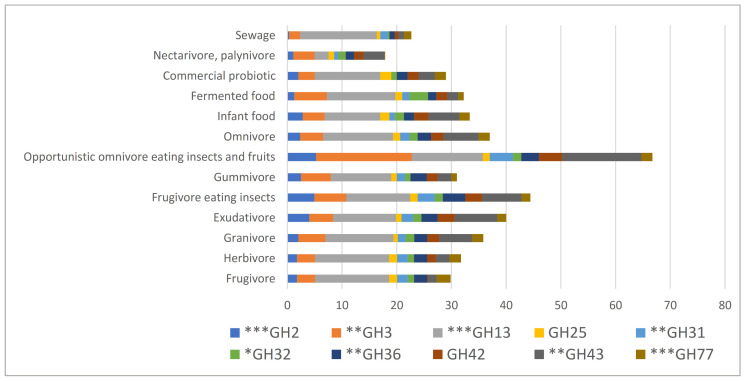

To examine the relationship between host diets and the genome sizes, the strains were classified into 13 dietary groups according to the feeding behavior and isolation sources of their hosts (Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S1). Genome sizes differed significantly among the different dietary groups (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 59.101, df = 13, p-value = 7.603 × 10−8) (Figure 2). Strains from bees showed the smallest genome sizes as previously reported [11]. The genome sizes of strains from herbivores and granivores were similar. Within primate origins, the genome sizes differed between human adults and pigs, feeding on both of plant and animal matter, and monkeys feeding on fruits (frugivore), plant exudates (exudativore), or gums (gummivore). The latter showed a larger genome size while those of human and pig strains were comparable to the sizes in herbivores (leafs) and granivores (grains). Strains from human infants exhibited an intermediate genome size. In all groups, no significant differences were found in the GC content (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Genome sizes of the strains in each dietary group. The box plot indicates the mean and standard deviation. Compro: Commercial probiotic; Exudi: Exudativore; Fermen: Fermented food; Frugi: Frugivore; Grani: Granivore; Gumi: Gummivore; Herbi: Herbivore; Infant: Infant food; Ins&Frugi: Frugivore eating insects; Insec: Nectarivore, palynivore; Omni: Omnivore; Oppori: Opportunistic omnivore eating fruits, leaves and insects; Sewg: Sewage. Exudi, gumi, and grani eat insects too. The colors in the boxplot show different host groups; Dark red: bats, Pink: monkey/apes, Blue: human/pigs, Yellow: other animals.

3.2. Distribution of Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes

The largest dietary difference between human adults and infants is milk oligosaccharides. Human milk contains diverse non-digestible oligosaccharides, classified into 13 structure series. As we shall see, GH33 (sialidase) is enriched only among strains from human infants, because sialic acid is a characteristic sugar in human milk. To investigate such metabolic correlation comprehensively, all carbohydrate-related genes were first investigated.

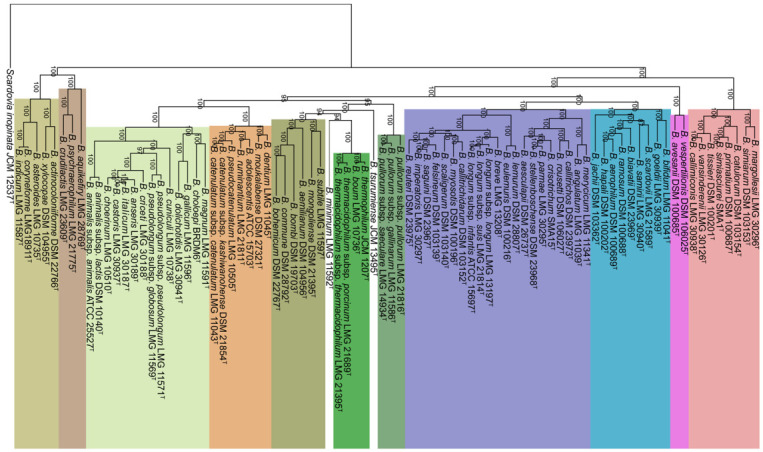

According to the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZy) system, each strain possessed from 33 to 166 genes (mean 88; SD ± 29.46). These genes spanned the wide range of CAZy families: 72 GHs (glycoside hydrolases), 17 GTs (glycosyltransferases), 10 CEs (carbohydrate esterases) and 2 PLs (polysaccharide lyases) and 20 CBMs (appended non-catalytic carbohydrate-binding modules). Shared among ≥80% of the strains were 10 GH families (GH2, GH3, GH13, GH25, GH31, GH32, GH36, GH42, GH43, and GH77), 5 GT families (GT2, GT4, GT28, GT35, and GT51), CE10, and CBM48. Among these families, the distribution significantly differed (p < 0.01) among hosts of different diets in 7 GH families (GH2, GH3, GH13, GH31, GH36, GH43, and GH77), 3 GT families (GT2, GT4, and GT35), CE10, and CBM48 (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S2). Considering the diversity of the gene distribution, we focused on the GH families.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the number of glycoside hydrolase genes in the different dietary groups. CAZyme families in >80% of the strains are shown. The significance by Kruskal-Wallis test is shown by asterisks. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

3.3. Clustering of Bifidobacterium Species Based on GH Families

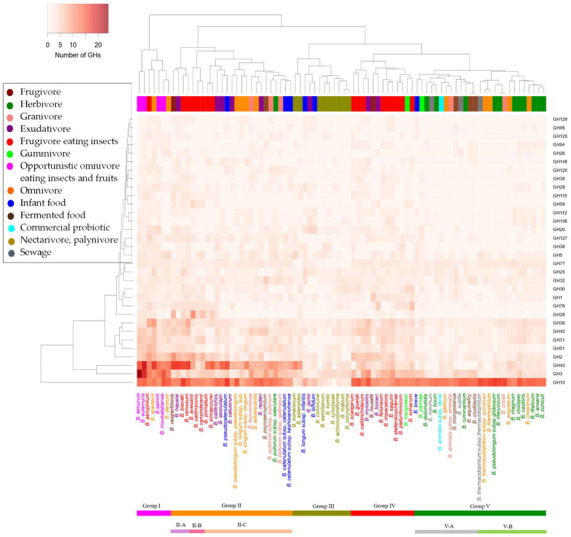

We next identified key GH families that delineate dietary difference of hosts. The clustering result of GH families became stable when 32 families that were present in >20% of all strains were used (see Methods). The clustering created Group I–V in Figure 4, with the following characteristic families (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Clustering of bifidobacterial species based on GH family genes. The heatmap shows the gene number for the selected GH families (families present in 20% of the strains). Pink: Group I with the opportunistic omnivores; Orange: Group II with omnivore, herbivore or insectivore; Gold: Group III with nectarivore; Red: Group IV with insectivore and frugivore; Green: Group V with herbivore and mixed diet. Each strain is highlighted with the color of the corresponding diet class.

Table 1.

Characteristic GH families in different dietary groups (p < 0.05).

| Dietary Groups | GH Families | Related Activities in Bifidobacteria [27] |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunistic omnivore eating insects and fruits and Frugivore eating insects (Group I, Group II-B and Group IV) |

GH13 | α-1,4-glucosidase, amylopullulanase, sucrose Phosphorylase, α-amylase |

| GH3 | β-glucosidase, β-hexosaminidase | |

| GH43 | Endo-1,5-α-l-arabinosidase, α-l-arabinofuranosidase, Endo-1,4-β-xylanase, β-1,4-xylosidase | |

| GH26 | Endo-1,4-β-mannosidase | |

| GH53 | Endogalactanase | |

| GH31 | α-xylosidase | |

| GH78 | α-l-rhamnosidase | |

| CBM67 | l-rhamnose binding activity | |

| Frugivore eating insects (Group II-B and Group IV) |

GH115 | xylan α-1,2-glucuronidase, α-(4-O-methyl)-glucuronidase |

| GH28 | Galacturan1,4-α-galacturonidase, pectinesterase | |

| Herbivore (Group V-B) |

GH94 | Cellobiose-phosphorylase |

| GH36 | α-galactosidase, raffinose synthase | |

| Infant food (Group II-C) |

GH33 | Sialidase |

| GH20 | β-hexosaminidase | |

| GH29 | α-l-fucosidase | |

| GH95 | α-l-fucosidase | |

| GH112 | Lacto-N-biosephosphorylase | |

| GH29 | α-l-fucosidase | |

| GH95 | α-l-fucosidase | |

| Nectarivore and Palynivore (Group III) |

GH65 | α,α-trehalase |

| GH13 * | α-1,4-glucosidase, amylopullulanase, sucrose Phosphorylase, α-amylase | |

| GT20 | α,α-trehalose-phosphate synthase | |

| GT35 * | glycogen or starch phosphorylase | |

| CBM48 * | appended to GH13 modules | |

| CE10 * | arylesterase |

Asterisks indicate significantly low occurrences.

Group I included strains with the largest number of GH genes. This group reflected species from opportunistic omnivore eating insects and fruits. The group had high numbers of GH43 and GH3 genes associated with degradation of complex plant polysaccharides like xylan, arabinan or arabinoxylan. This suggested that these GH genes were adapted to the hosts of mixed diets (omnivore and frugivore).

Group II included strains with a high number of GH43 but low GH3. The group included 25 species and was further divided into three: subgroup II-A, -B and -C. The subgroup II-C possessed low numbers of GH2, GH28, GH59 and GH115. The dietary pattern of the hosts varied: omnivore, herbivore, frugivore, insectivore and exudativore.

Group III included bee isolates and two infant isolates. This group possessed a very low number of GH13. This result was supported by previous studies where the GHs from the insects clustered separately [26]. GH13 enzymes are involved in degradation of starches and malto-oligosaccharides, and such sugars are usually scarce in diets of bees and infants.

Group IV included strains from hosts of insect and fruit diet. This group had the second highest gene counts for GHs after Group I, which suggested that the species from frugivorous hosts possessed more GH genes.

Group V included the largest number of strains. This group had the lowest GH gene counts, where many of the GH families were mostly absent (e.g., no GH28, GH38 and GH115). The group was further divided into two subgroups (subgroup V-A and V-B). Subgroup V-B was strains from herbivorous hosts while subgroup V-A included strains from hosts of mixed dietary habits.

In Figure 4, the strains from insectivorous and frugivorous hosts were spread in separate clusters (Group IV and Group II). This discrepancy was attributed to the strains isolated from tamarins, whose diet is mainly insects and fruits but sometimes small amphibians. When the host diet was more complex (e.g., opportunistic omnivore, and frugivore and folivore), more diverse GH families and more genes were found. On the contrary, the strains from hosts with simple feeding habits (e.g., pure herbivore and nectarivore) possessed smaller number of families and genes. A good example was four subspecies of B. longum: subsp. longum, subsp. suis, subsp. infantis, and subsp. suillum. Of the three subspecies whose genomes were available, the former two belonged to Group II, while subsp. infantis belonged to Group III, due to different diets of their hosts. Hosts of the subsp. longum and subsp. suis are omnivores, while subsp. infantis is only seen in human infants. Infants generally consume simple diet, including breast milk and infant formulae, and thus storage of numerous GHs is not essential for the strain.

To test whether the GH contents follow the dietary pattern rather than the phylogeny, we checked the phylogenetic signal for GH genes. The analysis showed weak phylogenetic signal with Bloomberg’s K value closer to 0 (K = 0.448). Phylogenetic correlogram analysis detected nonsignificant autocorrelation above the phylogenetic distance of 0.1 (Supplementary Figure S3a). We also performed the LIPA analysis to identify clades with a high phylogenetic signal. Only two clades (Clade 1: Bifidobacterium eulemuris and Bifidobacterium lemurum; Clade 2: Bifidobacterium hapali, Bifidobacterium aerophilium, Bifidobacterium ramosum, Bifidobacterium biavatii, Bifidobacterium scardovii, and Bifidobacterium samirii) were detected with significant positive autocorrelation (p-value < 0.01) (Supplementary Figure S3b).

3.4. Comparison of Bifidobacterium Species from Multiple Host Animals

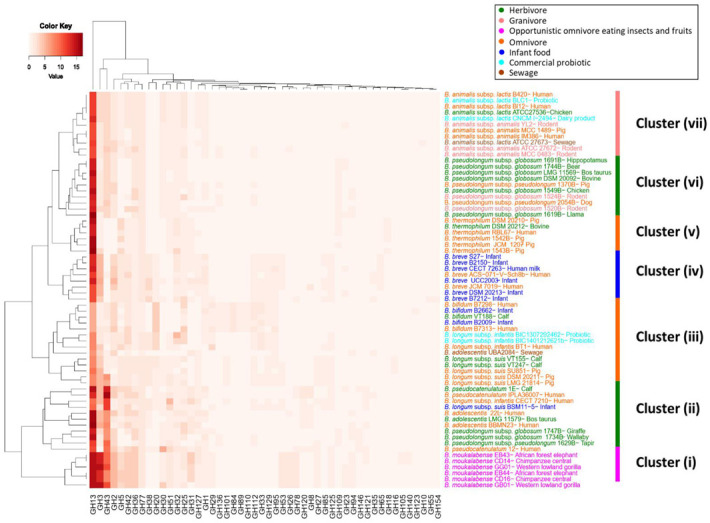

Some species were isolated from multiple host animals with different dietary patterns. To investigate their GHs, we selected 66 strains in 11 different species isolated from different hosts (Supplementary Table S2). Their clustering resulted in seven different groups, from Cluster (i) to Cluster (vii), among which five groups (Cluster (i), (iv), (v), (vi), and (vii)) cleanly corresponded to the species’ phylogeny (Bifidobacterium moukalabense, B. breve, Bifidobacterium thermophilum, B. pseudolongum, and B. animalis) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Clustering of 66 strains isolated from different sources based on their GHs. Heatmap displays the number of genes in GH families. Strains were colored according to their host dietary patterns as in the upper box. Strains were clustered in seven major groups: Cluster (i) Opportunistic omnivore; Cluster (ii) and Cluster (vi) Herbivore; Cluster (iii) and Cluster (v) Omnivore; Cluster (iv) Infant food; and Cluster (vii) Granivore and Insectivore.

The result suggested that strains within the same species shared similar GH families. Still, we could find characteristic GH families that coincided with host diet patterns. For example, B. moukalabense strains from gorilla, chimpanzee, and elephant possessed high numbers of GH families for plant carbohydrates (GH43, GH3, GH13, GH53, GH26 and GH78). B. thermophilum from pig, cow, and human lacked GH43 and GH2, and these families hydrolyze plant carbohydrates and milk carbohydrates, respectively (Table 2). B. bifidum strains were isolated from infants and calf and possessed high numbers of GH families for milk-origin carbohydrates (GH2, GH20, GH33, GH129 and GH84). Among the milk metabolizing families was GH33 (sialidase), whose abundance is statistically significant in B. bifidum, B. longum subsp. infantis, and B. breve only [28].

Table 2.

Characteristic GH families in the Bifidobacterium species with multiple hosts (p < 0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test).

| Family | Related Subfamilies | Significantly High | Significantly Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| GH1 | β-glucosidase, β-galactosidase | B. bifidum | B. longum subsp. suis |

| GH2 | β-galactosidase | all others | B. thermophilum |

| GH3 | β-glucosidase, β-hexosaminidase, β-glucosideglucohydrolase | B. thermophilum, B. bifidum | B. moukalabense |

| GH5 | β-mannosidase, β-glucosidase, β-exoglucanase | B. moukalabense | B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum |

| GH13 | α-1,4-glucosidase, amylopullulanase, sucrose phosphorylase, α-amylase | B. moukalabense | B. bifidum |

| GH20 | β-hexosaminidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH26 | Endo-1,4-β-mannosidase | B. moukalabense | all others |

| GH27 | α-galactosidase | B. moukalabense | all others |

| GH29 | α-L-fucosidase | B. bifidum | B. thermophilum |

| GH30 | β-d-xylosidase, endo-1,6-β-glucosidase, Glucosylceramidase | all others | B. thermophilum |

| GH31 | α-xylosidase | B. moukalabense | all others |

| GH32 | β-fructofuranosidase, sucrose-6-phosphatehydrolase | all others | B. bifidum |

| GH33 | Sialidase | B. bifidum | B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum |

| GH36 | α-galactosidase, raffinosesynthase | B. moukalabense | B. thermophilum |

| GH43 | Endo-1,5-α-l-arabinosidase, α-l-arabinofuranosidase, Endo-1,4-β-xylanase, β-1,4-xylosidase | all others | B. thermophilum |

| GH51 | α-L-arabinofuranosidase | B. moukalabense | B. bifidum |

| GH53 | Endogalactanase | B. moukalabense | B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum |

| GH77 | 4-α-glucanotransferase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH78 | α-l-rhamnosidase | B. moukalabense | all others |

| GH84 | α-l-rhamnosidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH85 | Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase D | B. longum subsp. suis | all others |

| GH89 | α-N-acetylglucosaminidase, β-N-hexosaminidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH94 | Cellobiose-phosphorylase | B. moukalabense | all others |

| GH95 | α-l-fucosidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH101 | endo-α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH109 | α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase | B. pseudolongum subsp. globosum | all others |

| GH110 | Exo-α-galactosidase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH112 | Lacto-N-biosephosphorylase | B. bifidum | all others |

| GH120 | β-xylosidase | B. pseudocatenulatum | all others |

| GH121 | β-galactosidase | B. pseudocatenulatum | all others |

| GH127 | β-l-arabinofuranosidase | B. moukalabense | all others |

To further investigate the variation of GH genes within the same species, we selected 45 strains of B. animalis subsp. lactis from 15 different isolation sources (Supplementary Table S3). Many strains were isolated from humans probably because of extensive use of probiotic strains (re-isolation). The clustering based on GH genes within subsp. lactis showed a single large isogenic group with a small, isolated group from dog, pig and food products (Supplementary Figure S4). This result supported that strains in the same species share similar GH patterns. The reason for the large deviation of some strains may be due to an application of unique strains as probiotics for animals. When all available B. animalis subsp. lactis strains were investigated for their GH genes, the 95% confidence interval for the number of GH genes in each family was never larger than 0.4 (Supplementary Table S5). This indicated that the number of GH genes did not differ much within the same species and justified our approach of using type strains to grasp the overview of metabolic capabilities in Bifidobacterium.

4. Conclusions

Genome-based features can deepen the understanding of the bacterial adaptation with host. We classified Bifidobacterium strains into five groups based on their GH genes, and the key GH families delineated the differences in host diet. The species from hosts having complex dietary habits possessed considerably more GH genes than those having simpler dietary patterns. Furthermore, a weak phylogenetic signal was confirmed for the distribution of GH genes.

In summary, bifidobacteria are adapted to their hosts’ dietary habits, and their GH composition is associated with the diet composition. However, the GH composition within the same species did not match the host diet well. The shuffling speed of GH genes is therefore not faster than the speciation and host adaptation.

Acknowledgments

Computational work was performed on the NIG supercomputer at the Research Organization of Information and Systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes12040609/s1. Figure S1: The number of bifidobacterial strains according to the dietary pattern of their respective hosts; Figure S2: The number of CAZyme and GH genes encoded by the strains in each dietary group; Figure S3: Phylogenetic correlogram and the Local Moran’s index for GH content for each type strain; Figure S4: Clustering of B. animalis subsp. lactis strains isolated from 15 different isolation sources, based on the number of GH genes. Table S1: Genomic features and diet information of all type strains; Table S2: Isolation sources and accession numbers for 66 strains isolated from various hosts; Table S3: Isolation sources and accession numbers for 45 B. animalis subsp. lactis strains; Table S4: Selection of GH families for clustering. The chosen set is shown in bold; Table S5: The distribution of GH genes in 434 different Bifidobacterium strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., T.K., and M.A.; methodology, M.S. and M.A.; validation, A.E., M.M., P.M.; resources, M.M., P.M.; data curation, M.S., M.M., P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MEXT KAKENHI (17K19248), NBDC Togo Database. M.S. was supported by SOKENDAI Student Dispatch Program (2018,2019). A.E. was supported by NIG-JOINT (2018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All genetic data are available from the GenBank/ENA/DDBJ repository. Accession numbers of all strains are summarized in Supplementary files; Tables S1–S3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alberoni D., Gaggìa F., Baffoni L., Modesto M.M., Biavati B., Di Gioia D. Bifidobacterium xylocopae sp. nov. and Bifidobacterium aemilianum sp. nov., from the carpenter bee (Xylocopa violacea) digestive tract. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;42:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modesto M., Watanabe K., Arita M., Satti M., Oki K., Sciavilla P., Patavino C., Cammà C., Michelini S., Sgorbati B., et al. Bifidobacterium jacchi sp. nov., isolated from the faeces of a baby common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019;69:2477–2485. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modesto M., Satti M., Watanabe K., Puglisi E., Morelli L., Huang C.-H., Liou J.-S., Miyashita M., Tamura T., Saito S., et al. Characterization of Bifidobacterium species in feaces of the Egyptian fruit bat: Description of B. vespertilionis sp. nov. and B. rousetti sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;42:126017. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2019.126017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duranti S., Lugli G.A., Napoli S., Anzalone R., Milani C., Mancabelli L., Alessandri G., Turroni F., Ossiprandi M.C., Van Sinderen D., et al. Characterization of the phylogenetic diversity of five novel species belonging to the genus Bifidobacterium: Bifidobacterium castoris sp. nov., Bifidobacterium callimiconis sp. nov., Bifidobacterium goeldii sp. nov., Bifidobacterium samirii sp. nov. and Bifidobacterium dolichotidis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019;69:1288–1298. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugli G.A., Mangifesta M., Duranti S., Anzalone R., Milani C., Mancabelli L., Alessandri G., Turroni F., Ossiprandi M.C., van Sinderen D., et al. Phylogenetic classification of six novel species belonging to the genus Bifidobacterium comprising Bifidobacterium anseris sp. nov., Bifidobacterium criceti sp. nov., Bifidobacterium imperatoris sp. nov., Bifidobacterium italicum sp. nov., Bifidobacterium margollesii sp. nov. and Bifidobacterium parmae sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;41:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trovatelli L.D., Crociani F., Pedinotti M., Scardovi V. Bifidobacterium pullorum sp. nov.: A new species isolated from chicken feces and a related group of bifidobacteria isolated from rabbit feces. Arch. Microbiol. 1974;98:187–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00425281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Z., Zhang W., Guo C., Yang X., Liu W., Wu Y., Song Y., Kwok L.Y., Cui Y., Menghe B., et al. Comparative Genomic Analysis of 45 Type Strains of the Genus Bifidobacterium: A Snapshot of Its Genetic Diversity and Evolution. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milani C., Lugli G.A., Duranti S., Turroni F., Bottacini F., Mangifesta M., Sanchez B., Viappiani A., Mancabelli L., Taminiau B., et al. Genomic Encyclopedia of Type Strains of the Genus Bifidobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:6290–6302. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02308-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottacini F., Medini D., Pavesi A., Turroni F., Foroni E., Riley D., Giubellini V., Tettelin H., Van Sinderen D., Ventura M. Comparative genomics of the genus Bifidobacterium. Microbiology. 2010;156:3243–3254. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.039545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez C.I., Martiny J.B.H. Evolutionary relationships among bifidobacteria and their hosts and environments. BMC Genom. 2020;21:26. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bottacini F., Milani C., Turroni F., Sánchez B., Foroni E., Duranti S., Serafini F., Viappiani A., Strati F., Ferrarini A., et al. Bifidobacterium asteroides PRL2011 Genome Analysis Reveals Clues for Colonization of the Insect Gut. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanizawa Y., Fujisawa T., Nakamura Y. DFAST: A flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1037–1039. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contreras-Moreira B., Vinuesa P. GET_HOMOLOGUES, a Versatile Software Package for Scalable and Robust Microbial Pangenome Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:7696–7701. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02411-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L., Stoeckert C.J., Roos D.S. OrthoMCL: Identification of Ortholog Groups for Eukaryotic Genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satti M., Tanizawa Y., Endo A., Arita M. Comparative analysis of probiotic bacteria based on a new definition of core genome. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1142/S0219720018400127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H., Yohe T., Huang L., Entwistle S., Wu P., Yang Z., Busk P.K., Xu Y., Yin Y. dbCAN2: A meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W95–W101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldón T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letunic I., Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keck F., Rimet F., Bouchez A., François K. Phylosignal: An R package to measure, test, and explore the phylogenetic signal. Ecol. Evol. 2016;6:2774–2780. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blomberg S.P., Garland T., Jr., Ives A.R. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: Behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution. 2003;57:717–745. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lugli G.A., Milani C., Duranti S., Alessandri G., Turroni F., Mancabelli L., Tatoni D., Ossiprandi M.C., Van Sinderen D., Ventura M. Isolation of novel gut bifidobacteria using a combination of metagenomic and cultivation approaches. Genome Biol. 2019;20:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens J.R., Hallinan E.V., Hauser M.D. The ecology and evolution of patience in two New World monkeys. Biol. Lett. 2005;1:223–226. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwiecinski G.G., Griffiths T.A. Rousettus egyptiacus. Mamm. Species. 1999;611:1–9. doi: 10.2307/3504411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milani C., Lugli G.A., Duranti S., Turroni F., Mancabelli L., Ferrario C., Mangifesta M., Hevia A., Viappiani A., Scholz M., et al. Bifidobacteria exhibit social behavior through carbohydrate resource sharing in the gut. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15782. doi: 10.1038/srep15782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Callaghan A., van Sinderen D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:925. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward R.E., Niñonuevo M., Mills D.A., Lebrilla C.B., German J.B. In vitro fermentability of human milk oligosaccharides by several strains of bifidobacteria. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:1398–1405. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All genetic data are available from the GenBank/ENA/DDBJ repository. Accession numbers of all strains are summarized in Supplementary files; Tables S1–S3.