Abstract

Countries increasingly compete to attract and retain human capital. However, empirical studies, particularly those of migrants moving back to developing countries, have been limited due to the lack of education-specific migration flow data. Drawing on census microdata from IPUMS, we derive flow data by level of education and age group to quantify the level of return migration and examine the educational and age profile of return migrants for a global sample of 60 countries representing 70% of the world population. We show that return migrants account for a significant share of in-migration flows, particularly in Africa and Latin America, and, in all countries but six, return migrants are more educated than the population in the migrants’ country of birth. Our age decomposition reveals that young adults contribute the most to the positive educational selectivity of return migrants, particularly in Africa and Asia. While this paper does not quantify the net effect of return migration on education levels, it underlines the importance of the human capital contributions of young adult returnees.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11113-021-09655-6.

Keywords: Return migration, International migration, Brain circulation, Brain drain, Educational selectivity, IPUMS

Introduction

Highly skilled migration plays a central role in today’s knowledge economy and the global competition to attract and retain human capital (Kerr et al., 2016). Most OECD countries have been successful in attracting a large number of tertiary-educated migrants from developing countries (Carrington & Detragiache, 1998), while many countries in the global south have faced net population losses to international migration (UN, 2019), often combined with a net loss of human capital (Beine et al., 2008). Because existing studies typically conceptualize developing countries as origins and economically developed countries as destinations (Docquier et al., 2005), human capital mobility has been analyzed mainly through the lens of the brain drain, and little is known about the educational selectivity of south-to-south migrants or the role of return migration in redistributing human capital to developing countries. In an effort to address this gap, Artuç et al. (2014) examined highly-skilled migration to non-OECD countries, revealing that migration to non-OECD countries accounts for about 20% of all migration of the highly-skilled, with a significant proportion of these migrants originating from the least developed countries.

Recent evidence suggests that return migrants (i.e., migrants who return to their country of birth after a period of residence abroad) may account for as much as 25% of international migration flows globally (Azose & Raftery, 2019). Brain circulation has received increasing attention, with a growing literature on integration and return intentions (Anniste & Tammaru, 2014; Carling & Pettersen, 2014), transnational networks and practices (Carling & Erdal, 2014; de Haas & Fokkema, 2011), the economic determinants of return migration (de Haas et al. 2015), and international students (King & Raghuram, 2013). While there have been detailed case studies providing in-depth analysis of particular streams of return migration to specific countries, there is a need for a global understanding of the links between return migration and education to establish the extent to which countries in different regions and at different levels of development succeed in attracting skilled return migrants.

Return migration may occur as a planned part of a life course, or because migrants have discovered that opportunities in the destination were not what they anticipated (Borjas & Bratsberg, 1996). The return decision is shaped by a migrant’s origin, age at entry, education, ties to family and origin, time at the destination, and degree of integration there (Carling & Pettersen, 2014; Jensen & Pedersen, 2007). Crises and other structural changes can also affect return decisions (Bygnes, 2017). Most migrants want to preserve their access to a destination, so restrictions on re-entry to destination countries (often imposed in the wake of a crisis) can discourage returns to the origin (Constant & Zimmermann, 2011; Czaika & de Haas, 2017; Flahaux, 2017; Massey & Pren, 2012). A number of studies have explored how migrants and return migrants may be positively or negatively selected for education, and some studies have found that return migration can intensify the type of selection characterizing the migrant population left in the destination (Borjas & Bratsberg, 1996; Feliciano, 2005; Rooth & Saarela, 2007). Educational selectivity of return migrants is the result of two selection processes: the first at the time of out-migration and the second at the time of return. Some studies have compared the educational profile of migrants to non-migrants left in the origin (i.e., the first process) (Feliciano, 2005), but few studies compare the educational profile of return-migrants to the non-migrant population in the origin. In this paper, to assess the contribution of return migration to education levels in the origin, we focus on the result of both selection processes, rather than attempting to separate the effects of one process from the other.

The dearth of comparative research on return migration predominantly stems from data limitations (Willekens et al. 2016). Comparative analysis of the selectivity of migration has typically relied on stock data based on country of birth, which do not record return migrants and do not provide an up-to-date picture of migration processes. While these limitations can be overcome by flow data, which measure the number of migrants entering or leaving a country during a given period, existing flow estimates are not disaggregated by level of education (Abel & Cohen, 2019; Abel & Sander, 2014; Azose & Raftery, 2019). To address these limitations, this paper draws on census microdata from IPUMS-International (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International) to measure migration flows to 60 countries in order to establish (1) levels of return migration across a wide range of countries and (2) the educational and age profiles of return migrants, compared with populations in their countries of birth. This represents an important step in understanding the educational selectivity of return migrants. However, as cross-national datasets on migrants such as IPUMS-International do not capture outflows, it is not possible to quantify the net effect of international migration on education composition at this scale.

Data and Methods

The IPUMS-International database, maintained by the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota (IPUMS 2019), is the largest global repository of individual census data. At the time of writing, IPUMS held census micro samples for 98 countries, of which 60 recorded both recent international migration and country of birth.1 We use the most recent data available, drawn from the 2010 census round (2005–2014) for 43 countries, and from the 2000 census round (1995–2004) for the remaining 17 countries. The exact census year for each country is listed in Fig. 3. While the years of data collection differ among some countries, our selection of countries and their groupings maximize the cross-national comparison of the educational profiles of return migrants for a global sample of countries at different levels of development. Our sample comprises 16 countries in Africa, 12 in Asia, 18 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 14 in Europe and North America,2 together over 80 million individual observations that represent more than 70% of the world population.

Fig. 3.

Percentage contribution of each age group to the NDI by country. The percentage contribution of each age group to the overall NDI is calculated as the NDI of the age group weighted by the share of the age group in the total flow of return migrants, as shown in Eq. 2

Migration can be measured in three principal ways—as an event, as a transition or as a duration—which are not directly comparable (Bell et al., 2002). In our study, we have selected IPUMS samples for countries that have a migration transition measure based on one of two approaches, dependent on the migration-related questions asked in the country’s census.3 The first migrant transition measure is based on responses to questions on the country of residence at a fixed interval prior to the census period. While most countries measure migration over a 5 year interval, 15 of the 60 countries4 in our study measure migration over a 1 year interval. The second migrant transition measure is based on responses to questions on the place of previous residence (where the response indicates the individual was abroad) and the duration of residence in the current location. These two approaches to measuring migrant transitions provide equivalent counts of persons when the fixed interval length in the first and duration of residence in the second are the same (Bell et al., 2015). We restrict our analysis to subjects aged 25–65 to capture people of working age who in most cases have already completed their education. Scholars and governments employ a range of measures of return migration, depending on how and where data is collected (in countries of origin or destination) and whether the data allows for direct or indirect measurement (Dumont & Spielvogel, 2008). In this paper, we quantify the incidence of return migration by estimating the share of return migrants as a percentage of all in-migrants during the observation period. We use the term “in-migrants” here because “immigrants” is typically understood to exclude native returnees.

The majority of previous studies on the human capital of return migrants have focused on immigration to OECD countries, and many of these studies are restricted to tertiary-educated migrants who are deemed essential to knowledge economies. However, in low-income countries where universal primary education has not been achieved, individuals with secondary educations also contribute essential skills to society (Lutz & KC, 2011). Consequently, we do not restrict our attention to tertiary-educated individuals but compare the entire educational distribution of migrants and non-migrants. In IPUMS, educational attainment is classified into four levels (no primary, primary, secondary, and tertiary) based on the International Standard Classification of Education (UNESCO, 2011). To measure educational selectivity, we use the net difference index (NDI) (Feliciano, 2005), based on return migrants and non-migrants’ educational distributions, a measure originally introduced by Lieberson (1976, 1980).

| 1 |

where subscript c refers to the country of interest.

Ie—the proportion of return migrants with level of education e.

NMe—the proportion of non-migrants with level of education e.

CIe—the cumulated proportion of return migrants with level of education below e.

CNMe the cumulated proportion of non-migrants with level of education below e.

An NDI of 0.35 indicates that return migrants’ educational attainment exceeds that of the non-migrant population of country c 35% more often than the non-migrants’ education exceeds that of return migrants from country c. The higher the NDI, the more educated return migrants are relative to the non-migrant population of country c; a value of 1 indicates that all return migrants are more educated than the non-migrant population of country c, while negative values indicate that return migrants are overall less educated than the non-migrant population.

We then decompose this index by age group to establish the relative contribution of each age group to the educational profiles of their countries of birth. Using index a to denote different age groups, the NDI of each country can be written as a sum of age-specific NDIs (NDIc,a) weighted by the share of each age group in the total flow of return migrants (Pc,a) (Dudel et al. 2020):

| 2 |

We use this weighted expression to separate the contribution of each age group to the overall NDI. For ease of interpretation and to facilitate direct comparison between countries, we express the contribution of each group as a percentage of the overall NDI. The data can be found in the Online Supplemental Material.

Results

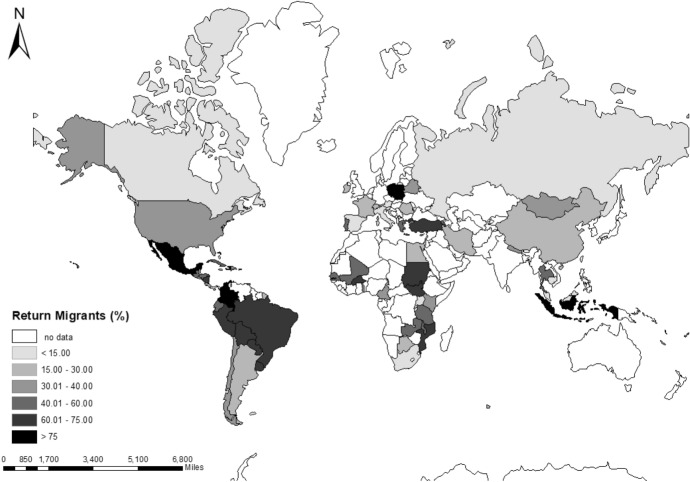

Across the 60 countries, the share of return migrants averages 42.2% of all in-migrants, but varies significantly both within and among regions as shown in Fig. 1. Among regions, the proportion of return migrants is highest in Latin America (55.9%), particularly in Mexico (90.4%) and Haiti (85.1%), but it is below 27.1% in El Salvador, Costa Rica and Argentina. Africa is the region with the second highest share of return migrants (43.1%), although there are large variations, the share of return migrants being above 60% in South Sudan, Burkina Faso, Sudan and Mozambique, but 20% or less in Egypt, Uganda and South Africa. Europe and North America, treated as a single region, is the region with the lowest share of return migrants (28.2%); the share is particularly low in Spain, Slovenia, and Canada, where less than 10% of in-migrants are return migrants. In contrast, return migrants dominate migration flows to Poland (98.8%), Portugal (44.7%) and Greece (42.2%). Finally, with a mean of 36.9%, Asia occupies an intermediary position, although this regional average conceals large variations from highs of over 70% in Turkey and Indonesia to lows under 20% in China, Russia and Cambodia. The results indicate that return migration accounts for a large share of in-migration in many countries, particularly in the developing world. We find some correlation between return and development in the origin, with the share of return migrants and the Human Development Index (HDI)5 returning a correlation coefficient of −0.33 across regions, and −0.71 in Africa. This may be because the least developed countries receive proportionally fewer immigrants than countries at more advanced levels of development and thus a significant share of their inflows are return migrants.

Fig. 1.

Share of return migrants as a percentage of all in-migrants. Return migrants to China include individuals returning from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan

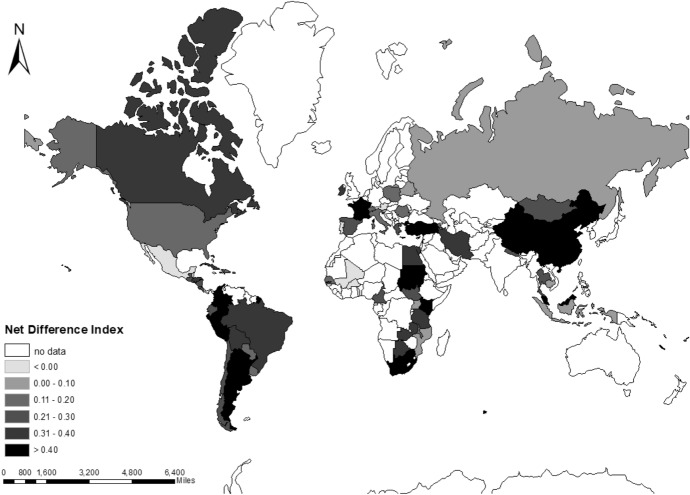

We now turn our attention to the educational profiles of return migrants by mapping the NDI. Figure 2 shows that in all countries but six (Austria, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mexico, Portugal and Togo), return migrants are positively selected, compared to the population in their country of birth. This suggests the widespread importance of brain circulation and the role of return migrants in raising overall education levels in their countries of birth. The NDI averages 0.24 and varies among regions, from a high of 0.27 in Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean, to 0.25 in Africa, and a low of 0.16 in Europe and North America.

Fig. 2.

Net Difference Index. The Net Difference Index (NDI) varies from −1 to 1. Positive values indicate that return migrants are on average more educated that the non-migrant population in their country of birth. The higher the NDI, the more educated return migrants are relative to the non-migrant population in their country of birth. Only six countries display negative values: Austria, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mexico, Portugal and Togo

Within Africa, there are wide variations that appear to be correlated with levels of human development, with the HDI and NDI returning a correlation coefficient of 0.65. Rather than a simple causal relationship between development and educational selectivity, there are multiple relationships at work and migration policy regimes are likely to exert some influence on the NDI. Latin America and the Caribbean displays a more homogeneous picture, with all countries showing positive NDIs except for Mexico (NDI = −0.04). Important variations occur within Asia, with countries like China, Iran, Malaysia, and Turkey reporting high positive educational selectivity (NDI > 0.35), whereas moderate values are observed in Armenia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal, and Thailand. In Europe and North America, the NDI is positive but moderate with the exception of France, Canada, and Ireland, which have the highest values, and Portugal and Austria, which display negative values.

To obtain a more fine-grained understanding of the educational profiles of return migrants, Fig. 3 reports the percentage contribution of each age group to the NDI. In the majority of countries, it is largely young adults, aged 25–34, who drive up the NDI, both because they represent a large share of return migrants and because they tend to be more educated than older migrants. For example, in Botswana, where 39% of in-migrants are return migrants, young adults aged 25–34 contribute 84% of the country’s NDI of 0.39. In 13 of the 16 African countries with a positive NDI, young adults contribute more than half of the NDI, which underlines the importance of young adult returnee contributions to raising the average level of human capital in their home countries. This is even more pronounced in Asia, where all 12 countries in the sample have positive NDIs, and in 9 of these countries, young adults contribute more than 50% of the NDI. It is not the case in Iran, where a greater share of returnees are between the ages of 35 and 44. The reverse situation characterizes only two countries, Burkina Faso and Cambodia, where young adults are negatively selected in terms of education, while other age groups contribute positively to the educational profile of returnees. Latin America and the Caribbean displays a relatively uniform age pattern, although one less skewed toward young adults, with the 35–44 age group contributing to NDI to a greater extent than in most African and Asian countries. Age decomposition reveals that Mexican returnees from all groups are negatively selected. In Europe, the negative NDI displayed by Portugal is clearly the result of older, less educated migrants returning home. A similar process occurs in Italy, Greece, and Spain, but the positive educational selectivity of young return migrants, particularly in Greece, more than compensates for the return of older, less educated migrants. Of the 12 European countries in our sample, Austria stands as the only one where all age groups are negatively selected, while Slovenia displays a mixed pattern. In Greece, Ireland, Italy, France, Belarus, and Spain, young adults dominate the flow of return migrants, whereas in Poland, Canada, the United States, and Switzerland, migrants over the age of 35 are proportionally more important.

Comparison of the 2000 and 2010 Census Rounds

Evidence from Europe suggests that migrants consider conditions in both origins and destinations, and when global economic conditions deteriorate, they may be less likely to return to the origin (Zaiceva & Zimmermann, 2016). Restrictions on migration, often imposed in the wake of crises, also tend to discourage returns, as migrants strive to avoid losing access to the destination. These processes are likely to underpin some of the variations observed among our study countries, which were based on data drawn from different years. For a subset of 24 countries where data were available for both the 2000 and 2010 census rounds, we compared the share of return migrants before and after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 and found that no clear patterns could be identified. Country ranking remained broadly stable through the two census rounds with a sample mean at 38.97% at the 2000 census round, compared to 36.80% at the 2010 census round. Mexico, Brazil, Portugal, and Indonesia consistently had the highest shares of return migrants, whereas Spain, Canada, South Africa, and France, maintained some of the lowest shares of return migrants over the two census rounds. Figure 4 compares the educational profile of return migrants at the 2000 and 2010 census rounds for these 24 countries. Ten countries had a stable NDI, while in seven countries there was a decrease (including Canada, Ecuador, and Indonesia), and in seven other countries there was an increase (including Iran, Cambodia, and Kenya). Cambodia and Mexico were the only two countries that moved between positive and negative selectivity between the two census rounds. The overall finding of positive selectivity remains.

Fig. 4.

Change in Net Difference Index, 2000 and 2010 census rounds

Conclusion and Discussion

Despite recent data advances, our knowledge of return migration remains fragmentary. Existing global flow estimates are not disaggregated by level of education, which has hampered progress in understanding brain circulation, particularly outside OECD countries. Drawing on census data from IPUMS-International, we have found for a global sample of 60 countries that return migrants account for a large share of in-migrants, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean (55.9%) and Africa (43.1%), followed by Asia (36.9%) and Europe and North America (28.2%). These results show that return migration is an integral component of the global migration system and the circulation of human capital. Results also provide qualified support to recent flow estimates that revealed a high volume of return migrants (Azose & Raftery, 2019), while providing additional insights into their educational and age profiles.

Previous studies have explored the educational selectivity of return migrants using data from a smaller range of countries or a particular region. However, little is known about the scope and prevalence of this selectivity around the world. In the present study, we provide an overview of the educational characteristics of return migrants to 60 countries, comparing them to non-migrants in the origins they return to. We find positive educational selectivity in 90% of the countries examined, a result that underlines the breadth of return migrants’ contributions to raising the overall levels of education in their countries of birth. In Africa, the variations that exist among countries appear to be related to levels of human development more so than in other regions. African countries with higher levels of development attract proportionally more educated returnees than countries with lower levels of development. Disaggregating educational selectivity by age revealed that the 24–35-year-old age group contributes most to the positive educational selectivity of return migrants, particularly in Africa and Asia, and to a lesser extent, also in North America and Europe. This result underlines the key role of young adults in raising overall human capital levels in their countries of birth when they return after a period of residence abroad, although the census data employed here does not permit us to establish whether return migrants gained the qualifications abroad or in the home country before emigrating. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the majority of educated return migrants are spread across a broader age range, 24–45. In order to better understand the cross-variations in the educational selectivity of return migration, and to account for the six countries where return migrants are less educated than the non-migrant population, additional research is required, including research on the return of international students.

In this study, we focused on aggregate measures. A more detailed understanding of the individual selection processes underpinning these results is required to establish (1) at what stages of the migrant life course educational selectivity occurs, including with respect to ages of emigration and return, and time spent in a destination, and (2) how education levels are related to dynamics of integration and transnationalism in various destinations for migrants from particular origins. For example, is the negative educational selectivity of migrants returning to Mexico the result of a negative selection when leaving Mexico, or is that that only the less educated decide to return? Such questions are not possible to decipher using the IPUMS-International data. Instead, they are best explored through longitudinal survey data on migrant educational histories. However, our study provides a useful starting point for researchers to select case study countries for further investigation. An additional limitation of our study is that we are unable to quantify the combined effect of emigration and return migration on educational composition in migrants’ countries of birth, as this is partially dependent on levels of emigration that cannot be measured from census data. Some of the countries observed are likely to be experiencing a brain drain by losing more human capital than they gain (Beine et al., 2008). To undertake an analysis of net human capital effects across countries would require global data or estimates of immigration and emigration flows by education level across many countries, which are yet to be produced.

In light of this study, policymakers may consider the extent to which COVID-19-related restrictions on migration may discourage the return of migrants and impede their contributions to education levels in their countries of origin. Countries that aim to maintain or improve their human capital may want to consider how migrants of different ages are affected by restrictions, what programs might encourage the return of educated migrants in the current context, and what alternative means could be used to raise levels of education to compensate for potential declines in return migration.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgement

We thank Xueting Li for assistance with data preparation, and we thank Dagmara Laukova for producing the maps.

Funding

The study was supported by Philosophy and Social Science Fund of Shanghai (CN) (Grant No. 2020BSH009) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41871142).

Footnotes

India, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Morocco record recent international migration but not country of birth at their census and therefore had to be excluded. For China, data from the 2005 mini-census was used.

Mexico is part of Latin America and North America. To avoid counting it twice, for the purpose of comparing regions, we include it in “Latin America and the Caribbean” rather than “Europe and North America.”

Migration transition data is by the far the most common method of measuring migration in censuses.

Austria, Burkina Faso, Canada, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Poland, Spain, Sudan, South Sudan, the United States, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

The HDI is a composite index measuring average achievement in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living. We use HDI estimates from 2008, the median of the year of the censuses used in this study (UNDP, 2019).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abel GJ, Cohen JE. Bilateral international migration flow estimates for 200 countries. Scientific Data. 2019;6:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0089-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel GJ, Sander NE. Quantifying global international migration flows. Science. 2014;343:1520–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1248676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anniste K, Tammaru T. Ethnic differences in integration levels and return migration intentions: A study of Estonian migrants in Finland. Demographic Research. 2014;30:377–412. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artuç, E., Docquier, F., Özden, Ç., & Parsons, C. (2014). A global assessment of human capital mobility: The role of non-OECD destinations. The World Bank

- Azose JJ, Raftery AE. Estimation of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116:116–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722334116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beine M, Docquier F, Rapoport H. Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: Winners and losers. The Economic Journal. 2008;118:631–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, et al. Cross-national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A. 2002;165(3):435–464. doi: 10.1111/1467-985X.00247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Charles-Edwards E, Ueffing P, Stillwell J, Kupiszewski M, Kupiszewska D. Internal migration and development: Comparing migration intensities around the world. Population and Development Review. 2015;41:33–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ, Bratsberg B. Who leaves? The out-migration of the foreign-born. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1996;78:165–176. doi: 10.2307/2109856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bygnes S. Are they leaving because of the crisis? The sociological significance of anomie as a motivation for migration. Sociology. 2017;51:258–273. doi: 10.1177/0038038515589300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carling J, Erdal MB. Return migration and transnationalism: How are the two connected? International Migration. 2014;52:2–12. doi: 10.1111/imig.12180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carling J, Pettersen SV. Return migration intentions in the integration–transnationalism matrix. International Migration. 2014;52:13–30. doi: 10.1111/imig.12161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, M. W. & Detragiache, M. E. (1998). How big is the brain drain? IMF Working Paper WP/98/102. International Monetary Fund

- Constant AF, Zimmermann KF. Circular and repeat migration: Counts of exits and years away from the host country. Population Research and Policy Review. 2011;30:495–515. doi: 10.1007/s11113-010-9198-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czaika M, de Haas H. The effect of visas on migration processes. International Migration Review. 2017;51:893–926. doi: 10.1111/imre.12261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas H, Fokkema T. The effects of integration and transnational ties on international return migration intentions. Demographic Research. 2011;25:755–782. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas H, Fokkema T, Fihri MF. Return migration as failure or success? Journal of International Migration and Integration. 2015;16:415–429. doi: 10.1007/s12134-014-0344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier, F., Lohest, O., & Marfouk, A. (2005). Brain drain in developing regions (1990–2000). IZA Discussion Paper No1668

- Dudel C, Riffe T, Acosta E, van Raalte A, Strozza C, Myrskylä M. Monitoring trends and differences in COVID-19 case-fatality rates using decomposition methods: Contributions of age structure and age-specific fatality. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0238904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont JC, Spielvogel G. International migration outlook Part III: Return migration, A new perspective. Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano C. Educational selectivity in US immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography. 2005;42:131–152. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flahaux M-L. The role of migration policy changes in Europe for return migration to Senegal. International Migration Review. 2017;51:868–892. doi: 10.1111/imre.12248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPUMS. (2019). Minnesota Population Center, Integrated public use microdata series, International: Version 7.2

- Jensen P, Pedersen PJ. To stay or not to stay? Out-migration of immigrants from Denmark. International Migration. 2007;45:87–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00428.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr SP, Kerr W, Özden Ç, Parsons C. Global talent flows. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2016;30:83–106. doi: 10.1257/jep.30.4.83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King R, Raghuram P. International student migration: Mapping the field and new research agendas. Population, Space and Place. 2013;19:127–137. doi: 10.1002/psp.1746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberson S. Rank-sum comparisons between groups. Sociological Methodology. 1976;7:276–291. doi: 10.2307/270713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberson S. A piece of the pie: Blacks and white immigrants since 1880. University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz W, KC S. Global human capital: Integrating education and population. Science. 2011;333:587–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1206964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Pren KA. Unintended Consequences of US Immigration Policy: Explaining the Post-1965 Surge from Latin America. Population and Development Review. 2012;38:1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooth D-O, Saarela J. Selection in migration and return migration: Evidence from micro data. Economics Letters. 2007;94:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2006.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. United Nations Department for Economic Social Affairs

- UNDP. (2019). Human development data (1990–2018). Retrieved December 4, 2020, from http://hdr.undp.org/en/data#

- UNESCO . Revision of the international standard classification of education. UNESCO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Willekens F, Massey D, Raymer J, Beauchemin C. International migration under the microscope. Science. 2016;352:897–899. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaiceva, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2016). Returning home at times of trouble? Return migration of EU enlargement migrants during the crisis. In M. Kahanec & K. F. Zimmermann (Eds.), Labor migration, EU enlargement, and the great recession (pp. 397–418). Springer

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.