BACKGROUND

Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines were approved in December 2020 and vaccinations have since commenced1. Both vaccines reported efficacy rates > 90% during clinical trials1. Adequate vaccine uptake is necessary to effectively combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

Though African Americans are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 compared to other racial groups in the USA, a survey of US adults showed that African Americans had the lowest COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate2. Historically, African American adults are less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive recommended vaccines partly due to a perceived higher risk of side effects and distrust in the healthcare system3.

It is unclear how long natural immunity from a previous COVID-19 infection lasts, with some studies reporting up to 6 months4. Therefore, the center for disease control and prevention (CDC) recently recommended vaccination regardless of previous infection5. We evaluated the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination among African American patients after recovery from COVID-19 infection. This study was conducted during the development stages of COVID-19 vaccines and there was no definitive CDC on vaccination in recovered patients at the time.

METHODS

African American patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection at the Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, GA, between April 1, 2020, and May 30, 2020, were asked to participate in the study after recovery and discharge from the hospital. Participants completed a survey in July 2020, on the likelihood to accept a “proven safe and effective” vaccine and factors impacting their decisions. The survey questions on reasons for potentially declining vaccination were developed based on previous research on influenza vaccine acceptance in the USA3. Respondents were given information on COVID-19 vaccines from the CDC and Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices working group updates in June, 20206.

Patients’ demographic and comorbidity data were obtained from the electronic health record system. The study was approved by the Morehouse School of Medicine institutional review board and verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants.

FINDINGS

Out of 132 eligible patients, 119 completed the survey. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of surveyed patients. The median age was 64 years (IQR, 54.5–73.5 years) and 58% were men. The most prevalent comorbidity was hypertension (68%) followed by diabetes mellitus (33%) and heart failure (20%). Overall, 30% responded they would accept a vaccine COVID-19 vaccine, 54% responded they would not, while 16% were undecided. On chi-squared analysis, male sex and uninsured status were associated with a higher chance of accepting vaccination while patients with congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension were more likely to decline.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptability

| Variables | Total N (%) | Intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N (%) | Undecided N (%) | Yes N (%) | Yes vs. no | Yes vs. undecided | ||

| Total, N (%) | 119 | 64 (54) | 19 (16) | 36 (30) | ||

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.25 | ||||

| Female | 50 (42) | 31 (62) | 8 (16) | 11 (22) | ||

| Male | 69 (57.9) | 33 (47.8) | 11 (15.9) | 25 (36.2) | ||

| Age (median 64y, IQR [54.5–73.5]) | 0.31 | 0.40 | ||||

| 18–34y | 7 (5.8) | 5 (71.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.5) | ||

| 35–49y | 16 (13.5) | 10 (62.5) | 3 (18.7) | 3 (18.7) | ||

| 50–74y | 69 (57.9) | 34 (49.2) | 13 (18.8) | 22 (31.8) | ||

| > 75y | 27 (22.6) | 15 (55.6) | 3 (11.1) | 9 (33.3) | ||

| Health insurance | <0.01 | 0.03 | ||||

| Medicare or Medicaid | 53 (44.5) | 37 (69.8) | 6 (11.3) | 10 (18.8) | ||

| Private insurance | 46 (38.6) | 21 (45.65) | 11 (23.9) | 14 (30.4) | ||

| Uninsured | 20 (16.8) | 6 (30) | 2 (10) | 12 (60) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Asthma | 15 (12.6) | 9 (60) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25 (21.1) | 16 (64) | 3 (12) | 6 (24) | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Cancer | 9 (7.6) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 0.18 | 0.26 |

| Congestive heart failure | 24 (20.2) | 16 (66.7) | 3 (12.5) | 5 (20.8) | <0.01 | 0.79 |

| Chronic kidney disease stage 3 and above | 14 (11.7) | 9 (64.2) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | 0.03 | 0.47 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 17 (14.9) | 10 (58.8) | 2 (11.7) | 5 (29.4) | 0.05 | 0.27 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 11 (9.2) | 7 (63.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.6) | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (32.7) | 24 (61.5) | 5 (12.8) | 10 (25.6) | <0.01 | 0.04 |

| HIV/AIDS | 5 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | - | - |

| Hypertension | 68 (57.4) | 36 (52.9) | 10 (14.7) | 22 (32.5) | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 8 (6.7) | 4 (50) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 0.08 | 0.49 |

| No of comorbidities | 0.30 | 0.02 | ||||

| No comorbidities | 22 (18.4) | 13 (59.1) | 2 (9.1) | 7 (31.8) | ||

| ≥ 1 comorbidity | 97 (81.5) | 51 (52.6) | 17 (17.5) | 29 (29.9) | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.13 | 0.41 | ||||

| < 30 kg/m2 | 54 (45.4) | 25 (46.3) | 9 (16.7) | 20 (37.4) | ||

| ≥ 30 to < 35 kg/m2 | 8 (6.7) | 4 (50) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (37.5) | ||

| ≥ 35 kg/m2 | 57 (47.9) | 35 (61.4) | 9 (15.8) | 13 (22.8) | ||

| Current tobacco use | 0.25 | 0.57 | ||||

| No | 78 (65.5) | 41 (52.5) | 13 (16.7) | 24 (30.7) | ||

| Yes | 41 (34.5) | 23 (56.1) | 6 (14.6) | 12 (29.2) | ||

χ2 tests were used to estimate associations between participant characteristics and intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine. 2 separate χ2 tests and associated P values were calculated to better distinguish characteristics associated with responses of “yes” versus “no” and characteristics associated with responses of “yes” versus “undecided”

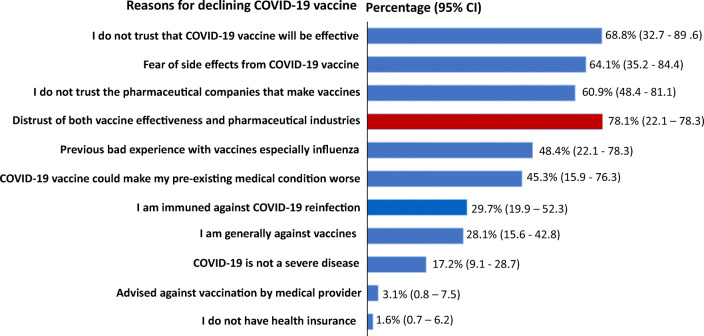

In Figure 1, the major reasons provided by participants for potentially declining COVID-19 vaccination were combination of distrust in the vaccine efficacy irrespective of what the research shows and distrust of the pharmaceutical companies that produce vaccines (78%), fear of vaccination side effects (65%), and perceived immunity against COVID-19 re-infection (29%).

Figure 1.

Reasons participants provided for responding “no” to COVID-19 vaccination. Respondents provided reasons in more than one category.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that only 3 out of 10 African American patients who recovered from COVID-19 infection will accept a “safe and effective” COVID-19 vaccine. Interestingly, this uptake rate is lower than previously reported among non-infected African Americans (40%)2. Though the perception of immunity against COVID-19 re-infection by almost one-third of the respondents may have contributed to the low acceptability rate, most of the patients intend to decline vaccination due to lack of trust in the vaccine effectiveness and pharmaceutical industries developing vaccines. These findings likely stem from skepticism towards healthcare research within the African American community justified by previous unethical mistreatment, experimentation, and exploitation3.

The drive for COVID-19 vaccination should not stop at developing a safe and effective vaccine. African Americans will likely trust and accept vaccines if recommended by their healthcare providers, especially if they share similar race or ethnicity and live in the same community3. Medical providers and community-based advocacy groups should work together to rebuild trust and dispel the misconceptions around COVID-19 vaccines.

This is a single-center cross-sectional study limited by its small sample size. We also recognize that the study was conducted early on during the pandemic and perspectives may have changed over time with more available information on COVID-19 vaccines. Additionally, our study population was restricted to African Americans which limits the ability to compare vaccine hesitancy with other ethnicities.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ledford H. Moderna COVID vaccine becomes second to get US authorization. Nature. Published online 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03593-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Malik AA, McFadden SAM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Quinn SC. African American adults and seasonal influenza vaccination: Changing our approach can move the needle. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14(3):719–723. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1376152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Figueiredo-Campos P, Blankenhaus B, Mota C, et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in COVID-19 patients and healthy volunteers up to six months post disease onset. Eur J Immunol. Published online 2020. 10.1002/eji.202048970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States. Updated January 6, 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html. Accessed on January 31, 2021

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Advisory Committee on Immunization and Practices’ Work Group Presentation and Updates on COVID-19 Vaccines. June 24, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/slides-2020-06.html. Accessed on July 7, 2020.