Abstract

Background:

Learner verification and revision (LV&R) is a research methodological approach to inform educational message design with the aim of producing suitable, actionable, and literacy appropriate messages to aid in awareness, adoption of healthy behaviors, and decision-making. It consists of a series of participatory steps that engage users throughout materials development, revision, and refinement. This approach is congruent with Healthy People 2030 communication objectives to improve access to information among diverse, multicultural, multilingual populations, and enhance health care quality toward health equity.

Brief description of activity:

To illustrate LV&R, we describe its use in three cancer education projects that produced targeted information about (1) inherited breast cancer among African Americans (brochure); (2) colorectal cancer screening among Latinos (photo novella and DVD); and (3) smoking-relapse prevention among patients receiving cancer treatment (video). We discuss rationale for its application in the three exemplars and extrapolate lessons learned from our experiences when using this approach.

Implementation:

A qualitative approach entailing individual or group-based discussions helped to examine the elements of learner verification (i.e., attraction, comprehension, self-efficacy, cultural acceptability, persuasion). The following steps are reported: (1) preparation of materials, interview guide, and recruitment; (2) interviewing of participants; and (3) evaluation of responses. Data were analyzed by use of a coding system that placed participant responses from each of the elements into data summary matrices. Findings informed revisions and refinement of materials.

Results:

LV&R was effectively applied across the three cancer education projects to enhance the suitability of the materials. As a result, the materials were improved by using clearer, more salient language to enhance comprehension and cultural acceptability, by integrating design elements such as prompts, headers, and stylistic edits to reduce text density, incorporating preferred colors and graphics to improve aesthetic appeal, and including actionable terms and words to bolster motivation and self-efficacy.

Lessons learned:

Results suggest that LV&R methodology can improve suitability of education materials through systematic, iterative steps that engage diverse, multicultural, multilingual populations. This approach is a critical participa-tory strategy toward health equity, and is appropriate in a variety of education, research, and clinical practice settings to improve health communications. [HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2021;5(1):e49–e59.]

Plain Language Summary:

This article describes the use of a systematic approach called “learner verification” used for developing educational materials. This approach involves obtaining feedback from audience members to ensure that the information is understandable, attractive in design, motivating, and culturally relevant.

Learner verification and revision (LV&R) is a methodological approach that provides researchers, practitioners, and educators an opportunity to assess and verify the suitability of health information with intended audiences. Numerous studies report the utility of LV&R methodology addressing biobanking, smoking cessation, fertility preservation, genetic testing, prostate, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC), hypertension, and brain donation awareness, among others (Hunter & Kelly, 2012; Koskan et al., 2012; Lambe et al., 2011; Luque et al., 2011; Matthews et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2014; Piñeiro et al., 2018; Vadaparampil et al., 2014). Importantly, these efforts have led to widespread dissemination and rigorous testing of evidence-based interventions that demonstrate positive results on behavioral and/or psychosocial outcomes (Brandon et al., 2004; Gwede et al., 2019; Kasting et al., 2019; Meltzer et al., 2018; Scherr et al., 2019).

LV&R supports Healthy People 2030 communication and health information technology objectives to increase access to health information that is relatable, actionable, and easy to understand, and aligns with national imperatives toward health care quality and health equity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Given the nature of a sociodemographically evolving environment, LV&R brings critical attention to perspectives and communication preferences of multicultural and multilingual communities, as well as groups that face predisposing factors that may influence health literacy and challenge understanding of health communications; including factors such as limited English proficiency, limited education attainment, financial hardship, race/ethnicity, age, and living with a disability or chronic illness. The connection between LV&R and health care improvements is difficult to fully disentangle because this practice alone may not solely equate to a measurable improvement in health care quality or health equity. Yet, the application of LV&R in cancer prevention and control efforts is an important signal toward health equity as part of a larger social justice mandate.

Relevantly, LV&R reinforces the use of participatory and empowering processes for creating information on health enhancement, disease prevention, and illness management, and it is beneficial in promoting health literacy (Meade, 2019). Materials developed using this approach can then be used in the context of research, clinical care, and in community outreach and engagement to address health disparities. This article describes the steps of LV&R, showcases its flexibility and versatility when developing information for communities that face predisposing conditions and/or who are multiethnic populations, and offers lessons learned and practical considerations in its application as a best practice for improving health communications.

Brief Description of Activity (Overview of Learner Verification)

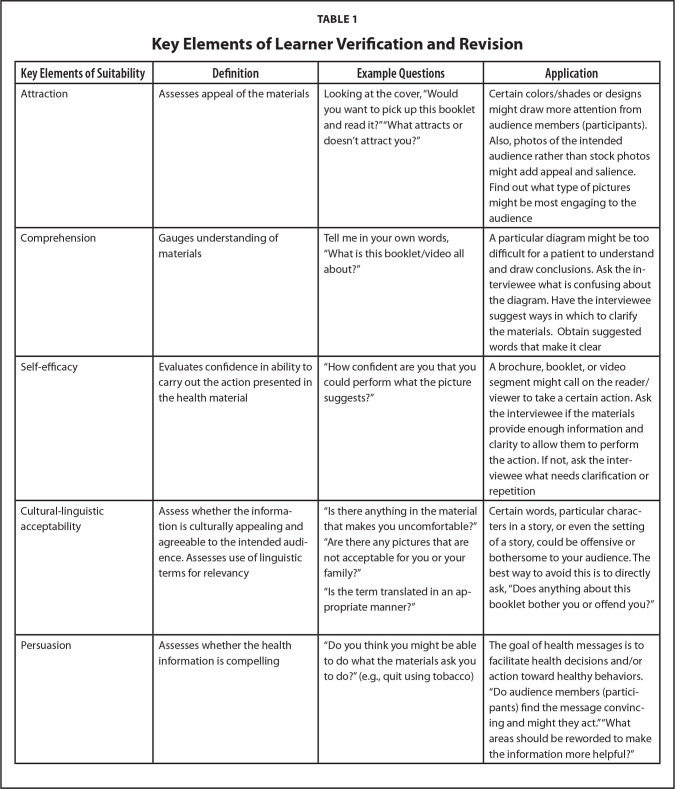

This multistep sequentially structured approach is learner-centric and builds on the underpinnings of qualitative research including use of semi-structured interview guides, probing questions, and follow-up to aid in revision and refinement. It is rigorous and geared toward achieving an educational product that reflects audiences' information needs and characteristics, such as literacy level, language, linguistics, and other sociocultural variables that may influence learning, understanding, and behavior change (C. Doak et al., 1985). The approach is compatible with multiple health behavior and education theories, such as the National Cancer Institute's Stages of Health Communication Model (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004), an organizing framework for ongoing assessment, feedback, and improvement throughout the lifecycle of material development. The LV&R approach likewise is informed by plain language and clear communication principles as outlined by such resources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Clear Communication Index (2014), the Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills book (C. Doak et al., 1996), and material assessment checklists (Meade, 2019; Shoemaker et al., 2013). Also, formative research adds a firm foundation to guiding the need for the material for which the research team is seeking feedback. The process of LV&R entails three basic steps: (1) preparation of materials, interview guide, and recruitment, (2) interviewing of participants, and (3) evaluating responses to revise accordingly (analysis) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Elements of Learner Verification and Revision

| Key Elements of Suitability | Definition | Example Questions | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attraction | Assesses appeal of the materials | Looking at the cover, “Would you want to pick up this booklet and read it?” “What attracts or doesn't attract you?” | Certain colors/shades or designs might draw more attention from audience members (participants). Also, photos of the intended audience rather than stock photos might add appeal and salience. Find out what type of pictures might be most engaging to the audience |

| Comprehension | Gauges understanding of materials | Tell me in your own words, “What is this booklet/video all about?” | A particular diagram might be too difficult for a patient to understand and draw conclusions. Ask the interviewee what is confusing about the diagram. Have the interviewee suggest ways in which to clarify the materials. Obtain suggested words that make it clear |

| Self-efficacy | Evaluates confidence in ability to carry out the action presented in the health material | “How confident are you that you could perform what the picture suggests?” | A brochure, booklet, or video segment might call on the reader/viewer to take a certain action. Ask the interviewee if the materials provide enough information and clarity to allow them to perform the action. If not, ask the interviewee what needs clarification or repetition |

| Cultural-linguistic acceptability | Assess whether the informa tion is culturally appealing and agreeable to the intended audi ence. Assesses use of linguistic terms for relevancy | “Is there anything in the material that makes you uncomfortable?” “Are there any pictures that are not acceptable for you or your family?” “Is the term translated in an appropriate manner?” | Certain words, particular characters in a story, or even the setting of a story, could be offensive or bothersome to your audience. The best way to avoid this is to directly ask, “Does anything about this booklet bother you or offend you?” |

| Persuasion | Assesses whether the health information is compelling | “Do you think you might be able to do what the materials ask you to do?” (e.g., quit using tobacco) | The goal of health messages is to facilitate health decisions and/or action toward healthy behaviors. “Do audience members (participants) find the message convincing and might they act.” “What areas should be reworded to make the information more helpful?” |

Step 1: Preparation of Materials, Interview Guide, and Recruitment

The purpose of the educational material and/or the intent of the planned intervention should be well-established, guided by questions like: “What is the need for the material?” and “What is the expected or outcome of the message?” Involving relevant stakeholders (e.g., community members, patients, clinicians) or convening a community advisory board (CAB) provide advisory perspectives that direct the process. We refer to this group of people as advisors to distinguish them from participants who are the people consented to participate in the LV&R sessions; their expert opinions further inform changes.

Step 1a - Developing a learner verification interview guide. Questions are developed and organized by grouping them according to key elements: attraction, comprehension, self-efficacy, cultural acceptability, and persuasion (Table 1). Using 4 to 6 questions per element prevents participants from being overwhelmed, and probes can encourage further discussion related to a given question.

Step 1b - Considerations for the interviewer(s). The primary goal of LV&R interviews is to elicit feedback on whether the information is understood, salient, and palatable, and to produce solutions to resolve these issues (C. Doak et al., 1996). Practice sessions with team members who will be conducting the interviews help to ensure consistent training to establish timing and pace, appropriate probes, logical sequence of questions, and adherence to the LV&R guide.

Step 1c - Recruitment. Setting a sample size, establishing an interview site, and securing Institutional Review Board approval are necessary prior to participant recruitment. The recommended sample size for LV&R depends upon the confidence you want, and how the materials will be used and distributed. Engaging a sample that includes at least 10 participants for local use may be sufficient, whereas a sample of 30 or more participants may be needed for national applicability of the materials (C. Doak et al., 1996).

LV&R is conducted via one-on-one interviews or small groups. Our team has found it effective to divide interviews into 2 to 3 iterations or rounds, with 5 to 10 participants per round, producing important findings in smaller local samples. For larger samples, 3 to 5 rounds of interviews (again, with 5–10 participants per round) ensure that crucial points are not missed. Having different participants for each round is preferred to broaden the scope of perspectives reflected in the review of the materials.

Sample size and number of iterations may need to be expanded due to the span of cultural diversity (e.g., urban vs. rural, country/region of origin, consideration of different sub-ethnic groups). The length of the materials is also a consideration. Figure 1 displays a suggested schema. With respect to location of interviews, easily accessible clinics or neighborhood sites (e.g., senior centers, libraries) may facilitate greater participation. Compensation for participants' time, offering refreshments (meal or snack), and arranging vouchers to cover transportation or childcare costs are means of enhancing LV&R session attendance.

Figure 1.

Sample learner verification and revision schema.

Step 2: Interview Participants

This step involves obtaining feedback from the participants about key elements of suitability (Table 1). People with limited literacy skills may be especially sensitive to an interview environment in which they believe “testing” is occurring. Introductory statements that review the purpose of the interview ask for their feedback (whether negative or positive) help set the stage for the interview. Audio recordings further capture points while allowing the interviewer to interact naturally without interruption of the conversation to write notes.

Step 3: Evaluate and Revise

After the completion of interviews, responses can be summarized and grouped by LV&R category and tabulated by the research team.

Step 3a - How to tabulate and analyze. Data are gathered from responses written into the LV&R interview guide by the interviewer. The responses (e.g., yes/no answers; and their selection: Sample A/Sample B) are tabulated for each category/element. Summaries can help isolate areas for improvement. Assigning each question a corresponding letter in the guide facilitates transcription and categorization (e.g., A = Attraction, C = Comprehension).

Step 3b - How decisions on edits and changes are made. Decisions on changes to materials are often made collaboratively between the research team and CAB members by discussing tabulations and most frequent participant responses obtained from open-ended questions. The number of participants that bring up a point can be a key consideration. For example, in terms of comprehension, several participants might mention difficulty with a certain word. This indicates that the word might need further explanation or replacement. Sometimes, a single participant may bring up a viewpoint not previously mentioned. The importance of that viewpoint can be further verified in subsequent rounds. Then, new versions of the materials are produced and retested by additional participants, typically up to three rounds. In some exemplars, the number of iterations may have been abbreviated due to extensive prior formative research.

Implementation and Results: Three Cancer Education Exemplars

To illustrate the LV&R process and lessons learned (see Table 2), we highlight three cancer education projects. These materials were newly developed to fill a specific gap in cancer education (e.g., a different language, cultural adaptation), and were not evaluated against other existing tools. Rather, each material served as its own quality control as drafts advanced in development. The Materials Checklist served as a dynamic reminder of essential design and development criteria to verify in the LV&R interview guide: format/layout, type, verbal content (including readability), visual content, and aesthetic quality (Meade, 2019).

Table 2.

Lessons Learned and Suggestions Per Steps in Learner Verification and Revision

| Step | Lessons Learned | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Preparing for LV&R | Effective learner verification interview guides require ample time to refine the order, sequence, and flow of questions Early and continuous involvement of advisors enhances the quality of the materials/intervention produced |

View iterations as an opportunity to continually improve the sharpness and clarity of the message Engage advisors to promote and advance the development of effective, logical, and understandable messages. Their insights and feedback are invaluable |

| 2: Interviewing | Critical to establishing rapport is creating a comfortable, welcoming environment (shared understanding vs. a test situation) in which participants do not feel pressured to provide socially desirable responses | Implement training and practice sessions to increase interviewer confidence and skills for prompting informed responses from interviewees |

| 3: Evaluating and revise | Participants may have difficulty imagining an end product Data from each iteration need to be carefully reviewed to uncover new information that may have been missed from prior iterations Providing participants with options on how to incorporate their suggestions/revisions is useful. This can improve richness of the feedback and can expedite the revision process |

Try to carry out LV&R interviews with solid draft versions of materials to allow for informed responses and feedback Review data on a continuous basis to inform revisions Solicit ideas from participants by providing multiple options on what the revisions could entail (e.g., three examples of a visual). This helps gives context and a point for reacting to the revisions |

Note: LV&R = learner verification and revision.

Exemplar 1: Development of a Brochure for Raising Awareness About Inherited Breast Cancer in Black Women

This project adapted a brochure that had previously been used to recruit women to a study offering genetic counseling and testing. It sought to meet a gap in making available culturally targeted materials to improve awareness about hereditary breast cancer for Black women. Details about the formative research and the original brochure development procedures (including more detailed examples of wording and visual changes made) are available in the development and design articles (Vadaparampil & Pal, 2010; Vadaparampil et al., 2011).

Description of LV&R method. LV&R eligibility criteria included female gender, self-identification as Black or African American, and membership in local organizations. To ensure representation in age, educational level, and personal cancer histories, recruitment included preselected local community-based organizations: (1) Black Student Union comprised of undergraduate college students from the local university (n = 9); (2) Sistahs Surviving Breast Cancer Support Group comprised of breast cancer survivors, along with their support system members (i.e., family, friends) (n = 28); and (3) a local chapter of the American Cancer Society Reach to Recovery Support Group comprised primarily of breast cancer survivors (n = 9). A meal was provided during the sessions. Participants were provided a $10 gift card, a breast cancer awareness pin, and a Susan G. Komen® for the Cure bookmark (Vadaparampil et al., 2011). Extensive formative work was carried out to create the brochure content, which was vetted with CAB members. As the purpose of the brochure was to raise awareness versus promote genetic counseling or testing, researchers focused on evaluating attractiveness, comprehension, and cultural acceptability. Thus, one round of LV&R was carried out using a group format (Vadaparampil & Pal, 2010).

Elements that Helped Identify Areas for Modification

Attraction. Several participants liked colors that represented the African American flag (red, black, and green) as compared to the colors of the original brochure (red and yellow). Younger women felt the brochure would appeal to older family members such as their mothers or aunts but did not feel it was meant for them. Improving attraction included modifying the color scheme and photographs to ensure that people from the entire target audience, including younger Black women, would identify with the educational material.

Comprehension. Findings revealed the need to modify specific aspects of the content to improve comprehension. For instance, the term “hereditary” was not well understood by participants and was substituted with “runs in the family.” Participants also expressed low levels of understanding the terms “genetic counseling and testing.” Providing detailed information about genetic counseling plus hereditary breast and ovarian cancer was beyond the scope of a brief brochure. As a result, information was refocused to introduce awareness to these topics with the idea that women who wanted more information could obtain resources or discuss the topic with a health provider.

Self-efficacy was not assessed given the project's aim.

Cultural-linguistic acceptability. With respect to cultural acceptability, several issues emerged. First, women preferred terms other than “women of color” to describe their community, and specifically preferred the term “Black.” Also, some women wanted specific information about why hereditary breast cancer was relevant to their community. Thus, including information unique to Black women enhanced both the cultural acceptability and personal relevance of the information.

Persuasion was not assessed given the project's aim.

Project results. As part of the campaign to raise awareness of inherited breast cancer, over 23,756 brochures were distributed using passive dissemination strategies among preexisting national social networks between January 2009 to November 2013 for use in both local and national venues (e.g., community health fairs, other events held by Black organizations). To trace brochure diffusion, an end-user survey was included with each brochure. Although the number of brochures disseminated was high, there was a low number of surveys returned (N = 219). The high number of brochures requested and distributed suggest that feedback incorporated from LV&R improved attractiveness, relevance, and cultural acceptability. Future research should pinpoint additional active dissemination strategies to enhance diffusion (Scherr et al., 2017).

Exemplar 2: Development of an Intervention (Photo Novella and Video) to Promote CRC Screening Among Latinos

The objective of the Latinos CARES (Colorectal Cancer Awareness, Research, Education, and Screening) project was to increase CRC screening uptake using a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) among Latinos age 50 to 75 years who were medically underserved, who were not up-to-date with screening recommendations, and who preferred medical information in Spanish. The team already had developed prior English-language interventions to promote CRC screening using LV&R approaches (Christy et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2017). Based on feedback from partnering Federally Qualified Health Care Centers (FQHCs), materials were needed for patients who preferred Spanish-language materials. Translation of materials would have been insufficient; therefore, it was necessary to “transcreate” (formative research + translation + cultural adaptation) the materials for a new audience. The content of the Latinos CARES intervention was informed by a series of focus groups that examined Latinos' awareness, knowledge, and perceptions about CRC screening and the feasibility of FIT adoption (Aguado Loi et al., 2018).

Description of LV&R method. Three rounds of LV&R interviews were completed. Participants were recruited and interviewed at settings such as clinics or libraries, and each round served a different purpose. Round 1 (n = 5) assessed photo novella suitability. Round 2 (n = 15, 5 interviews each) evaluated photo novella and video suitability separately, and then as a combined package. The video was played on a laptop and distributed in the form of a DVD for later viewing. The third round (n = 9) served as the final evaluative step to assess photo novella and video as a combined package. Revisions and modification of the materials took place before moving to subsequent rounds. Each participant received $25 for their participation.

Elements that Helped Identify Areas for Modification

Attraction. In the first round, the question, “Overall did the booklet keep your attention?” revealed that the booklet was missing bright colors and inviting pictures. Thus, the color scheme was revised to include reds, oranges, greens, and yellows. In the second round, the question, “What do you think about the size of the text and style of text in the booklet?” resulted in feedback that larger fonts and greater contrast of colors might improve text readability. Revisions included using lighter background colors, darkened font colors, and larger font size. Participants responded favorably to Round 3 modifications.

Comprehension. Round 1 participants were asked to review the materials and circle words and phrases that were difficult to understand, revealing difficulty with words such as polyps. This word was discussed with CAB members to select possible descriptor words from those given by participants to be retested in Round 2. Words such as, “Pelotas chiquitas” (small round tissue), “pedacito de carne” (small tissue), and “pequeño crecimiento” (small growth) were suggested. Other revisions from Round 2 included adding a table to highlight differences between screening tests and adding pictures to the comparison table to show the differences. Round 3 revealed that combining the descriptor terms for polyps into “pedacito de carne, un pequeño crecimiento” (small tissue or small growth) enabled quick understanding of the term. Differences among screening tests were better understood with the addition of pictures.

Self-efficacy. In Round 1, the question, “After reviewing the material, do you feel confident that you have enough information to talk to your doctor about getting a home stool test?” revealed that additional instructions were needed on how to perform a home stool test. Round 2 included more precise directions on how to complete the test. After making this modification, participants expressed confidence in their ability to perform a home stool test. Yet, participants still suggested more pictures for each step. Round 3 included visuals and then all participants expressed confidence in their ability to both ask their provider about a home stool test and perform a home stool test.

Cultural-linguistic acceptability. In Round 1, the LV&R guide included the direct translation of the question, “Is there anything about the booklet that bothers you?” A participant voiced concern that the direct Spanish translation of the word “bother” (moleste) in her country had a negative connotation. Thus, in Round 2 we instead used the word “disgusto” (displeasure) when asking the above question. With the right question, the team gathered feedback about a key cultural component of the photo novella (i.e., family influence on health). As a result, the booklet cover was revised to depict a family scene with the main character (a father) at his daughter's church wedding.

Persuasion. The question, “After getting these materials, do you think that you would get the FIT test?” revealed an otherwise overlooked issue. In Round 2, several people wanted to know whether the paper (tissue) the fecal matter sits on would float and/or clog plumbing. In Round 3, all participants expressed agreement to using the FIT test based on the changes made “el papel se disuelve y no dañara la plomería” (the paper dissolves and won't damage plumbing).

Project results. The Latinos CARES intervention (photo novella and video) was piloted in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (n = 76) to promote FIT uptake. Results demonstrated overall high uptake (87%), exceeding Healthy People 2020 screening objective of 70.5%. The intervention group, who received the “transcreated” health materials, demonstrated slightly higher FIT uptake (90%) than did the comparison group (83%), but this was not statistically significant (p = .379). Both intervention arms received a FIT kit, suggesting that access also is a key factor toward health equity (Gwede et al., 2019). Moreover, people in the Latinos CARES intervention group demonstrated greater postintervention increases in CRC awareness (p = .046) and susceptibility (p = .013). Improvements in CRC screening uptake contributed positively to the FQHCs Uniform Data System screening rates (which in Florida hover around 40%). Our team is currently testing these materials in a larger RCT.

Exemplar 3: Development of a Smoking-Relapse Prevention Intervention for Cancer Patients

The final exemplar captured the unique smoking relapse risk factors among cancer patients through a targeted self-help relapse-prevention intervention, drawing from one previously developed for the general population and found to be efficacious and cost-effective (Brandon et al., 2000; Brandon et al., 2004). Information on the benefits of staying smoke-free during cancer treatment and how to cope with urges to smoke was included in the intervention. Details about the development and LV&R findings are found in a prior publication (Meltzer et al., 2018).

Description of learner verification method. Extensive prior formative research (Díaz et al., 2016; Simmons et al., 2009), informed the content of the video that was tested with participants to provide feedback. Participants were identified via medical chart review and eligible to participate if they were receiving cancer treatment and had recently quit smoking. Two rounds of LV&R were completed, each with five participants. Interviews took place at the cancer center and lasted approximately 30 to 45 minutes. Participants were provided with $25 in recognition of their time.

Elements that Helped Identify Areas for Modification

Attraction. Interviews revealed that the overall attraction of the video could be improved by patient and provider testimonials that included on-screen text to identify who the person was speaking by name, to identify patients as “cancer survivors,” and to name the providers as specialists in their area (e.g., tobacco research specialist, cancer specialist). Participants preferred to see the names and titles each time the individual spoke. A second suggestion to enhance the attraction was to include additional patient quotes at the beginning to better engage the audience. Specifically, during patient testimonials, potent messages spoken simultaneously appeared in text on the screen to bolster the impact and appeal of the message (e.g., “I'm not going to let cigarettes conquer me”). These changes were well received in Round 2.

Comprehension. The initial draft of the video included suggestions for coping with smoking urges. Yet, participants wanted images to help them better understand coping strategies. As a result, footage of people relaxing or taking part in a support group was included versus simply listing coping strategies. Participants responded positively to these added visuals in Round 2.

Self-efficacy. Participants were asked whether they felt that the suggestions provided in the video were realistic and doable. Participants expressed a desire for greater information regarding the “tools” for cessation. In response, the discussion of nicotine replacement therapies was expanded. Round 2 interviews confirmed that participants felt that the strategies were feasible.

Cultural-linguistic acceptability. Participants were asked whether they could relate to the cancer survivors in the video. Overall, perceived cultural acceptability was high and the participants acknowledged the racial/ethnic diversity among patients in the video.

Persuasion. In Round 1, participants were asked whether the video could help a person remain smoke-free. This question resulted in two key changes. First, participants felt that the difficulty in quitting smoking should be emphasized even more. Second, participants felt that the “drama” could be enhanced to persuade patients to fully appreciate the need to stay smoke-free. To incorporate these suggestions, testimonials by former smokers that spoke to the challenges in quitting smoking were added.

Project results. The efficacy of the 14-minute educational video along with an accompanying series of self-help relapse prevention booklets were then tested in an RCT with 414 participants. Statistical analyses for the RCT are ongoing.

Lessons Learned and Implications

The methodological approach of LV&R contributes to health communication practice by creating suitable health information, and in turn, improving communication with intended audiences for new or adapted educational materials. This approach allows researchers, practitioners, and educators to identify features in materials that require clarification and improvement. Although methods were somewhat variable, each exemplar adhered to a rigorous and systematic process, whereby subsequent steps built upon key findings from prior steps.

Table 2 communicates an overview of lessons learned and suggestions per steps in LV&R. Regardless of intervention content and intended audience, several common themes emerged across the projects. Regardless of intervention content and intended audience, several common themes emerged across the projects. For example, CABs composed of diverse members were instrumental in both preliminary research directions and decisions made between LV&R rounds. Also, a thorough understanding of the interviewer's guide and experience in establishing rapport was essential for successful implementation of interviews. Shared among the studies were suggestions to provide samples of actual materials instead of asking participants to envision or imagine the future state of materials.

LV&R was helpful in linking communication theory and the practice of pedagogy to produce salient and clear materials for specific audiences. Still, LV&R takes time and planning, including the time required to create interview guides, recruit participants, schedule and conduct interviews, and produce multiple iterations of educational materials. Also, costs related to staff time, participant incentives, and material redesign and production are all planning considerations.

Given the nature of a demographically evolving landscape in the United States and beyond, LV&R is a methodological approach that has wide application for the development of health materials delivered via both printed and digital platforms (such as websites, apps). It can be used in other settings and extended to other topics and audiences. In future research, it might be beneficial to include measures that connect specific elements of LV&R activities (e.g., self-efficacy, persuasion) to other behavioral outcomes.

Conclusion

LV&R is a helpful methodological approach to improve the quality of health education materials by examining intended audience members' reactions to the elements of attraction, understanding, cultural acceptability, persuasion, and self-efficacy. Using feedback that contextually strives to frame information in ways (e.g., language, meaning, and cultural features) that resonate and fit peoples' everyday lives can assiduously and importantly advance the public health agenda toward health equity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cecelia Conrath Doak, MPH, (Patient Learning Associates, Inc.) for reviewing an early version of the manuscript.

References

- Aguado Loi, C. X., Martinez Tyson, D., Chavarria, E. A., Gutierrez, L., Klasko, L., Davis, S., Lopez, D., Johns, T., Meade, C. D., Gwede, C. K. (2018). ‘Simple and easy:’ providers' and Latinos' perceptions of the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colorectal cancer screening. Ethnicity & Health, 25(2), 206–221. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1418298 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, T. H., Collins, B. N., Juliano, L. M., & , Lazev, A. B. (2000). Preventing relapse among former smokers: A comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 103–113 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.103 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, T. H., Meade, C. D., Herzog, T. A., Chirikos, T. N., Webb, M. S., & , Cantor, A. B. (2004). Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: Dismantling the effects of amount of content versus contact. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 797–808 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.797 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2014). The CDC clear communication index. https://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/index.html

- Christy, S. M., Davis, S. N., Williams, K. R., Zhao, X., Govindaraju, S. K., Quinn, G. P., Vadaparampil, S. T., Lin, H. Y., Sutton, S. K., Roethzeim, R. R., Shibata, D., Meade, C. D., & , Gwede, C. K. (2016). A community-based trial of educational interventions with fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening uptake among blacks in community settings. Cancer, 122, 3288–3296 10.1002/cncr.30207 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S. N., Christy, S. M., Chavarria, E. A., Abdulla, R., Sutton, S. K., Schmidt, A. R., Vadaparampil, S. T., Quinn, G. P., Simmons, V. N., Ufondu, C. B., Ravindra, C., Schultz, I., Roetzheim, R. G., Shibata, D., Meade, C. D., & , Gwede, C. K. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent, targeted, low-literacy educational intervention compared with a nontargeted intervention to boost colorectal cancer screening with fecal immunochemical testing in community clinics. Cancer, 123, 1390–1400 10.1002/cncr.30481 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, D. B., Brandon, T. H., Sutton, S. K., Meltzer, L. R., Hoehn, H. J., Meade, C. D., Jacobsen, P. B., McCaffrey, J. C., Haura, E. B., Lin, H. Y., & , Simmons, V. N. (2016). Smoking relapse-prevention intervention for cancer patients: Study design and baseline data from the surviving SmokeFree randomized controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 50, 84–89 10.1016/j.cct.2016.07.015 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak, C., Doak, L., & Root, J. (1985). Teaching patients with low literacy skills (2nd ed.). J.B. Lippincott Company. [Google Scholar]

- Doak, C., Doak, L., & Root, J. (1996). Learner verification and revision of materials (2nd ed.). Lippincott-Raven Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gwede, C. K., Sutton, S. K., Chavarria, E. A., Gutierrez, L., Abdulla, R., Christy, S. M., Lopez, D., Sanchez, J., & , Meade, C. D. (2019). A culturally and linguistically salient pilot intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening among Latinos receiving care in a federally qualified health center. Health Education Research, 34(3), 310–320 10.1093/her/cyz010 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J., & , Kelly, P. J. (2012). Imagined anatomy and other lessons from learner verification interviews with Mexican immigrant women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 41(6), E1–E12 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01410.x PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasting, M. L., Conley, C. C., Hoogland, A. I., Scherr, C. L., Kim, J., Thapa, R., Reblin, M., Meade, C. D., Lee, M. C., Pal, T., Quinn, G. P., & , Vadaparampil, S. T. (2019). A randomized controlled intervention to promote readiness to genetic counseling for breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 28(5), 980–988 10.1002/pon.5059 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskan, A., Arevalo, M., Gwede, C. K., Quinn, G. P., Noel-Thomas, S. A., Luque, J. S., Wells, K. J., & , Meade, C. D. (2012). Ethics of clear health communication: Applying the CLEAN Look approach to communicate biobanking information for cancer research. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(4, Suppl), 58–66 10.1353/hpu.2012.0192 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambe, S., Cantwell, N., Islam, F., Horvath, K., & , Jefferson, A. L. (2011). Perceptions, knowledge, incentives, and barriers of brain donation among African American elders enrolled in an Alzheimer's research program. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 28–38 10.1093/geront/gnq063 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque, J. S., Rivers, B. M., Gwede, C. K., Kambon, M., Green, B. L., & , Meade, C. D. (2011). Barbershop communications on prostate cancer screening using barber health advisers. American Journal of Men's Health, 5(2), 129–139 10.1177/1557988310365167 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. K., Conrad, M., Kuhns, L., Vargas, M., & , King, A. C. (2013). Project Exhale: Preliminary evaluation of a tailored smoking cessation treatment for HIV-positive African American smokers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(1), 22–32 10.1089/apc.2012.0253 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade, C. D. (2019). Community health education. In Nies M. A. & McEwen M. (Eds.), Community/public health nursing: promoting the health of populations (7th ed., pp. 123–158). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer, L. R., Meade, C. D., Díaz, D. B., Carrington, M. S., Brandon, T. H., Jacobsen, P. B., McCaffrey, J. C., Haura, E. B., & , Simmons, V. N. (2018). Development of a targeted smoking relapse-prevention intervention for cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education, 33(2), 440–447 10.1007/s13187-016-1089-z PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D., Kashal, P., Quinn, G. P., Sawczyn, K. K., & , Termuhlen, A. M. (2014). Development of a Spanish language fertility educational brochure for pediatric oncology families. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 27(4), 202–209 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.10.004 PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro, B., Díaz, D. R., Monsalve, L. M., Martínez, Ú., Meade, C. D., Meltzer, L. R., Brandon, K. O., Unrod, M., Brandon, T. H., & , Simmons, V. N. (2018). Systematic transcreation of self-help smoking cessation materials for Hispanic/Latino Smokers: Improving cultural relevance and acceptability. Journal of Health Communication, 23(4), 350–359 10.1080/10810730.2018.1448487 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, C. L., Bomboka, L., Nelson, A., Pal, T., & , Vadaparampil, S. T. (2017). Tracking the dissemination of a culturally targeted brochure to promote awareness of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among Black women. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(5), 805–811 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.026 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, C. L., Nam, K., Augusto, B., Kasting, M. L., Caldwell, M., Lee, M. C., Meade, C. D., Pal, T., Quinn, G. P., Vadaparampil, S. T. (2019). A framework for pilot testing health risk video narratives. Health Communication, 35(7), 832–841 10.1080/10410236.2019.1598612 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, S. J., Wolf, M. S., & Brach, C. (2013). The patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT) and user's guide. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/patient-education/pemat.html [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, V. N., Litvin, E. B., Patel, R. D., Jacobsen, P. B., McCaffrey, J. C., Bepler, G., Quinn, G. P., & , Brandon, T. H. (2009). Patient-provider communication and perspectives on smoking cessation and relapse in the oncology setting. Patient Education and Counseling, 77(3), 398–403 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.024 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . (n.d.). Healthy People 2030: Health communication. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/health-communication

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . (2004). Making health communication programs work: A planner's guide, pink book. http://www.cancer.gov/publications/health-communication/pink-book.pdf

- Vadaparampil, S. T., Malo, T. L., Nam, K. M., Nelson, A., de la Cruz, C. Z., & , Quinn, G. P. (2014). From observation to intervention: Development of a psychoeducational intervention to increase uptake of BRCA genetic counseling among high-risk breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(4), 709–719 10.1007/s13187-014-0643-9 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil, S. T., & , Pal, T. (2010). Updating and refining a study brochure for a cancer registry-based study of BRCA mutations among young African American breast cancer patients: Lessons learned. Journal of Community Genetics, 1(2), 63–71 10.1007/s12687-010-0010-4 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil, S. T., Quinn, G. P., Gjyshi, A., & , Pal, T. (2011). Development of a brochure for increasing awareness of inherited breast cancer in black women. Genetic Testing and Molecular Bio-markers, 15(1–2), 59–67 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0102 PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]