Abstract

Mitochondria play an important role in controlling oocyte developmental competence. Our previous studies showed that glycine (Gly) can regulate mitochondrial function and improve oocyte maturation in vitro. However, the mechanisms by which Gly affects mitochondrial function during oocyte maturation in vitro have not been fully investigated. In this study, we induced a mitochondrial damage model in oocytes with the Bcl-2-specific antagonist ABT-199. We investigated whether Gly could reverse the mitochondrial dysfunction caused by ABT-199 exposure and whether it is related to calcium regulation. Our results showed that ABT-199 inhibited cumulus expansion, decreased the oocyte maturation rate and the intracellular glutathione (GSH) level, caused mitochondrial dysfunction, which was confirmed by decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and the expression of mitochondrial function-related genes PGC-1α, and increased reactiveoxygenspecies (ROS) levelsand the expression of apoptosis-associated genes Bax, Caspase-3, and Cyto C.More importantly, ABT-199-treated oocytes showed an increase in the intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) and had impaired cortical type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R1) distribution. Nevertheless, treatment with Gly significantly ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis, and Gly also regulated [Ca2+]i levels and IP3R1 cellular distribution, which further protects oocyte maturation in ABT-199-induced porcine oocytes.Taken together, our results indicate that Gly has a protective action against ABT-199-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in porcine oocytes.

Keywords: apoptosis, calcium, glycine, mitochondria, oocyte, oxidative stress

Introduction

Mitochondria are essential organelles because they supply oocytes with metabolic energy in the form of adenosine-5’ -triphosphate (ATP) generated by the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.In addition, they play pivotal roles in controlling oocyte developmental competence by regulating calcium (Ca2+) signaling, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and apoptosis induction. Some studies on oocytes and embryos from pigs (Brevini, 2005), cattle, and mice have indicated that mitochondria have key roles in shaping developmental competence.

The normal mitochondrial structure is crucial for the maintenance of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), which is the driving force behind ATP production and mitochondrial homeostasis. In mammals, the integrity of the mitochondrial outer membrane and ΔΨmis under the control of Bcl-2 family members and has a direct relationship to the apoptotic process (Ola et al., 2011).Bcl-2 is the founding member of the Bcl-2 protein family, and it must continually inhibit the function of Bax and Bak to ensure mitochondrial integrity and survival in healthy cells (Chipuk and Green, 2008). When the integrity of the mitochondrial outer membrane is damaged, proapoptotic factors are released from Bcl-2 and induce the oligomerization of Bax and Bak on the mitochondrial outer membrane (Antignani and Youle, 2006; Chipuk and Green, 2008). Mitochondria release soluble Cytochrome c (Cyto C)proteins from the intermembrane space to initiate caspase activation in the cytosol and thus apoptosis (Vaux, 2011).

Alternatively, defects in the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane can, therefore, cause calcium imbalance, and the abnormal increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ can also activate apoptosis factors of the Bcl-2 family and promote apoptosis. When stress causes microenvironmental changes, Ca2+ is released from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) and ryanodine receptor channels, thereby provoking Ca2+ signaling. Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload in oocytes results in increased ROS production, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, lowered ΔΨm, matrix swelling, and subsequent release of various apoptotic factors, including Cyto C, Caspases, or the activated Bcl-2 family, that lead to cellular apoptosis (Kim et al., 2008; Robker, 2012), which critically affects mitochondrial function (Decuypere et al., 2011). These channels accumulate in mitochondrial-associated membranes, which associate with the mitochondrial outer membrane. In contrast, ABT-199, a selective Bcl-2 inhibitor that induces apoptosis, causes loss of ΔΨm, which actively participates in programmed cell death (Chen et al., 2019).

Glycine (Gly) has the highest content of amino acids in the oviduct fluid, uterine fluid, and follicular fluid during dioestrus in sows by biochemical analysis. Gly plays an important role in the development of oocytes. However, when suffering external stimulation or stress, the synthesis of Gly in vivo cannot meet the metabolic needs of the body and requires exogenous supply. Our previous studies showed that Gly, a component of glutathione (GSH), plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial function in the in vitro maturation (IVM) of oocytes by decreasing ROS levels and increasing mitochondrial ΔΨm, ATP concentration, and Bcl-2 gene expression to reduce apoptosis (Li et al., 2018). Numerous other studies have confirmed that exogenous Gly supplementation can significantly increase the efficiency of IVM and in vitro fertilization (IVF) (Xia et al., 1995; Redel et al., 2016). Some studies believe that the effect of Gly on oocyte maturation depends on the synthesis of the antioxidant GSH (Wang et al., 2014a). Other studies suggest that Gly plays a protective role by maintaining the high physiological osmotic pressure of oocytes and embryos in vivo and in vitro (Miyoshi and Mizobe, 2014; Redel et al., 2016). In addition, some researchers still suggest that the protective effect of Gly is achieved by attenuating Ca2+ overload (Van den Eynden, 2009).

However, whether the effect of Gly on mitochondrial damage during oocyte maturation in vitro is related to the regulation of calcium level remains unknown. In the present study, we investigated whether Gly could reverse the mitochondrial dysfunction induced by exposure to the Bcl-2-specific antagonist ABT-199 and whether it is related to calcium regulation.

Materials and Methods

All procedures involving animal care and use standards were based upon the Guide for the Care and Use of Agricultural Animals in Research and Teaching, and humane slaughter practices followed the guidelines stated in the regulations on the administration of pig slaughtering of China.

Oocyte collection and IVM of oocytes

The ovaries were collected from a local slaughterhouse and transported to the laboratory within 2 h at 25 to 35 °C in 0.9% saline (w/v). Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from follicles with a diameter of 3 to 6 mm with an 18-gauge needle attached to a 20 mL disposable syringe. High-quality COCs were selected and washed three times in Tyrode’s lactate (TL)-HEPES-PVA (polyvinyl alcohol, 0.1%).Approximately, 80 COCs were placed into 500 μL IVM medium containing NCSU-37 medium supplemented with 10 IU/mL pregnant mare serum gonadotropin and 10 IU/mL human chorionic gonadotropin and incubated for 42 h at 38.5 °C under 5% CO2 in 95% humidified air for IVM. Treatments consisted of control media supplemented with 5 µM ABT-199 (Beyotime, GDC-0199) with or without two different concentrations of Gly for 42 h, namely the control (Control) group, 5 µM ABT-199 (ABT-199) group, 5 µM ABT-199 + 6 mM Gly (ABT+6 mM Gly) group, and 5 µM ABT-199 + 12 mM Gly (ABT+12 mM Gly) group were included. The oocyte maturation rate was calculated after 42 h.

Measurement of cumulus cell expansion degree

Cumulus cell expansion was measured directly under an inverted microscope (ix70, Olympus). The vertical as well as the horizontal diameter of mature COCs cumulus cells in all groups were measured, and 30 cells were measured in each group. In addition, the cumulus cells were denuded by gentle pipetting with 0.1% hyaluronidase; the first polar body extrusion served as a marker of nuclear maturation; and mature oocytes were collected for subsequent experiments.

Measurement of intracellular GSH and ROS levels in oocytes

The intracellular GSH and ROS levels of oocytes at the metaphase II (MII) stage were measured by CellTracker Blue CMF2HC (4-chloromethyl-6,8-difluoro-7-hydroxycoumarin; Invitrogen) and H2DCFDA (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) fluorescence assays. The intracellular GSH level is shown as blue fluorescence, and the ROS level is shown as green fluorescence. Briefly, oocytes from different groups were incubated (in the dark) in PBS–PVA containing 10 µM CMF2HC and 10 µM H2DCFDA for 20 min at 38.5 °C, washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS)–PVA, and fluorescence was observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with ultraviolet (UV) filters.Fluorescence intensities of the oocytes were analyzed using ImageJ software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The experiment was replicated three times with a group of 15 oocytes in each replicate.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i levels

The intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) level was detected by immunostaining as described in a previous report (Wang et al., 2017). Briefly, oocytes were incubated in the presence of 5 µM Fluo-3/AM (Beyotime) for 40 min at 38.5 °C and washed three times with PBS–PVA (without Ca2+). The oocytes were placed on slides containing antifade polyvinylpyrrolidone mounting medium. Then, the oocytes were observed under an Olympus fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensities of oocytes were analyzed using ImageJ software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence pixel values within a constant area from 25 different cytoplasmic regions were measured with background fluorescence values subtracted from the final values.

Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential in oocytes

The ΔΨm was analyzed by a Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Detection Kit with MitoTracker Red Chloromethyl-X-rosamine (CMXRos).Mature denuded oocytes were selected and washed in PBS–PVA three times. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, oocytes were stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos for 15 min at 38.5 °C and washed three times with PBS–PVA. Images of each oocyte were captured using an Olympus fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of oocytes was analyzed by ImageJ software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of Caspase-3 activity and apoptosis

Caspase-3 activity and apoptosis were detected by immunostaining using Caspase-3 Activity and Apoptosis Detection Kit for Live Cell (Beyotime) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Caspase-3 activity is shown as green fluorescence combined with GreenNuc Caspase-3 substrate, and the apoptosis is shown as red fluorescence by Annexin-V-mCherry. Then, the oocytes were observed under an Olympus fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence intensities of oocytes were analyzed using ImageJ software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence

Matured oocytes in different groups were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature (RT). After three washes in PBS–PVA for 5 min each, MII oocytes were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, blocked in blocking solution PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at RT, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with IP3 Receptor I Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Invitrogen, PA1901) diluted 1:200 in blocking solution.After three washes in PBS–PVA for 5 min each, oocytes were labeled with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Superclonal™ Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Invitrogen, A27034) diluted 1:500 in blocking solution for 45 min at RT in the dark. Samples were incubated with 10 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 10 min at 37 °C to label DNA. Stained oocytes were mounted beneath a coverslip using antifade mounting medium to retard photobleaching. The IP3R1 distribution patterns were analyzed using laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP5). Images were obtained using a digital camera (NIKON), and the mean gray values of fluorescence were measured using ImageJ software after background subtraction.

Quantitative real-time PCR

For the gene expression study, isolated denuded matured oocytes derived from 30 COCs from each group were separately sampled using a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. All samples were washed three times with PBS–PVA and stored at −80 °C until RNA was extracted. Total RNA was extracted using the Arcturus PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, KIT0204, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of extracted RNA was measured using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara, RR047AA) was used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA). The CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System was used for real-time PCR. Each 20 μL PCR sample contained 2 μL cDNA, 1 μL forward and reverse primers, 10 μL TB green premix ex Taq II (TLi RNaseH plus) (2×) (Takara), and 6 μL RNase-free dH2O. The amplification process consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 30 s. Specific primer sequences (Table 1) were designed using the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database.Relative gene expression levels were analyzed using the 2-∆∆CT method, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the internal control gene. For convenient comparison, the mean expression level of each gene was normalized to the Control group.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time-PCR

| Genes | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Product length, bp |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F: GATGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTGAAC | 153 |

| R: TGGGTGGAATCATACTGGAACA | ||

| Bax | F: CCGAAATGTTTGCTGACG | 232 |

| R: AGCCGATCTCGAAGGAAGT | ||

| Bcl-2 | F:ACCTGAATGACCACCTAGAGC | 281 |

| R:TCCGACTGAAGAGCGAAC | ||

| Caspase-3 | F:TTGGACTGTGGGATTGAGACG | 165 |

| R:CGCTGCACAAAGTGACTGGA | ||

| Cyto C | F:CTGCGAGTGGTGGATTGT | 222 |

| R:ATGCCTTTGTTCTTGTTGG | ||

| PGC-1α | F: TTCCGTATCACCACCCAAAT | 137 |

| R: ATCTACTGCCTGGGGACCTT |

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The data were analyzed using univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test using IBM-SPSS 23.0 statistical software. Percentage data (e.g., rates of immature, degeneration, and MII) were arcsine-transformed before analysis to ensure homogeneity of variance. Differences in gene expression were compared by Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of Gly on cumulus expansion and maturation efficiency of porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

Based on preliminary results, 5 µM ABT-199 was selected as the final concentration group of the Bcl-2 inhibitor, and 6 mM Gly and 12 mM Gly were added as the rescue groups. We investigated the cumulus expansion and meiotic maturation of COCs by measuring the expansion diameter of cumulus cells and calculated the rates of degradation and maturation by microscopy. Poor expansion and a low rate of maturation were evident in COCs cultured in the presence of ABT-199. The diameter of COCs was measured and recorded after IVM, as shown in Figure 1. As expected, the cumulus expansion diameter of the ABT-199 group was lower than that of the Control group and ABT+12 mM Gly group (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences among the ABT+6 mM Gly group and the other groups.

Figure 1.

Effectof Gly on cumulus expansion of porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. Measurement of cumulus cell expansion in COCs after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. (A) The morphology of COCs matured in vitro. (B) The vertical and horizontal diameters of mature COC cumulus cells were measured in all groups and are presented as the mean ± SEM, n = 3 experimental replicates with more than 30 COCs per treatment group. Bar = 200 μm. Different letters (a, b) above bars show significant differences (P < 0.05).

Similar results were obtained for the oocyte maturation rate and death rate. The maturation rate of the ABT-199 group was lower than that of the Control group and ABT+12 mM Gly group (56.43 ± 2.63 vs. 68.65 ± 3.07, 67.09 ± 3.77, P < 0.05). There were no differences among the ABT+6 mM Gly group (P > 0.05). The death rate of the ABT-199 group was higher than the Control group (P < 0.05), but rescue groups were not significantly different among the ABT-199 group and Control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of Gly on maturation of porcine oocytes in vitro treated with ABT-199

| Group | Oocytes examined | Immature, % | Degeneration, % | MII, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 300 | 15.02 ± 5.55 | 16.32 ± 3.95a | 68.65 ± 3.07a |

| ABT-199 | 331 | 16.33 ± 3.01 | 27.23 ± 3.13b | 56.43 ± 2.63b |

| ABT+6 mM Gly | 325 | 14.30 ± 3.28 | 20.35 ± 1.19ab | 65.33 ± 2.10ab |

| ABT+12 mM Gly | 307 | 9.71 ± 3.29 | 23.16 ± 4.21ab | 67.09 ± 3.77a |

a,bValues with different superscripts in the same column were significantly different (P < 0.05).

These results suggest that the significantly reduced cumulus expansion and maturation efficiency of porcine oocytes in 5 µM ABT-199-treated COCs wererestored by 12 mM Gly treatment.

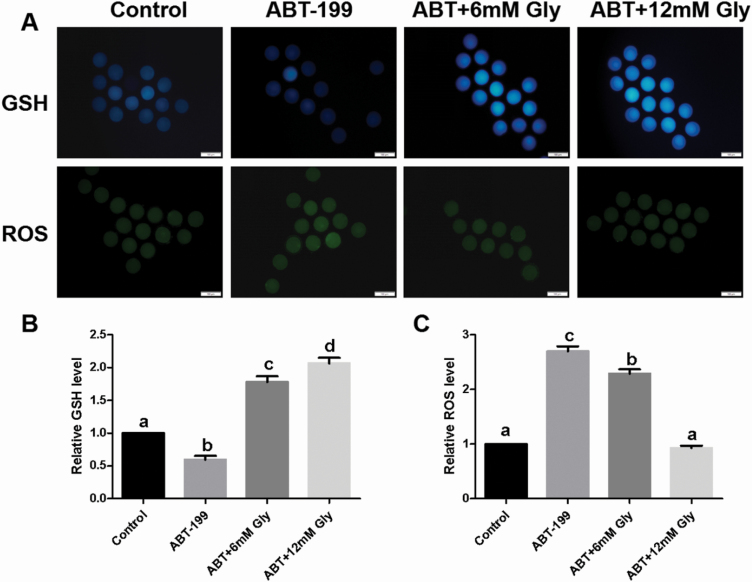

Effect of Gly on GSH and ROS levels in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

Mitochondrial dysfunction generally induces oxidative stress, and we detected the GSH and ROS levels in porcine oocytes after ABT-199 treatment and Gly supplementation. The results in Figure 2 show that the GSH level of the 5 µM ABT-199 group was lower than that of the Control group (P < 0.05). However, when Gly was added to IVM culture medium, the level of GSH in oocytes increased significantly. Consistent with this finding, the levels of ROS in the 5 µM ABT-199 group were higher than those in the Control group (P < 0.05). However, adding 6 mM Gly to IVM culture medium reduced the ROS level of oocytes, and, after 12 mM Gly treatment, the ROS level of oocytes was not significantly different from that of the Control group.

Figure 2.

Effect of Gly on GSH and ROS levels in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. (A) Immunofluorescent staining of GSH and ROS in MII porcine oocytes after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. Blue, GSH; green, ROS. Bar = 200 µm. (B-C) Fluorescence intensity analysis of the GSH and ROS signals by ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters (a–d) above bars show significant differences (P < 0.05).

Effect of Gly on mitochondrial function in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

The results showed that the ΔΨm of the ABT-199 group was lower than that of the Control group (P < 0.05). However, the ΔΨm level was restored after adding 12 mM Gly (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Gly on mitochondrial ΔΨm inporcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. (A) MitoTracker Red CMXRos signals in MII porcine oocytes after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. Red, MitoTracker Red CMXRos; blue, DNA. Bar = 200 µm. (B) Fluorescence intensity analysis of the MitoTracker Red CMXRos signal by ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters (a and b) above bars show significant differences (P < 0.05).

In addition, the mRNA expression of genes associated with mitochondrial function of mature oocytes was evaluated. As shown in Figure 7A, PGC-1α was decreased in oocytes treated with ABT-199 compared with the control (P < 0.05); after Gly treatment, the mRNA expression of mitochondrial function-related genes was ameliorated. These results indicate the protective role of Gly on ABT-199-induced mitochondrial function.

Figure 7.

Effect of Gly on mitochondrial function and apoptosis in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. (A) The relative mRNA expression of mitochondrial function-related genes after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. (B, C) The relative mRNA expression of apoptosis-related genes after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation.

Effect of Gly on Ca2+ levels in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

Calcium is distributed throughout the cytoplasm in MII oocytes. The results of the fluorescence probe Fluo-3AM (5 µM) showed that the level of Ca2+ in the ABT-199 group was higher than that in the Control group (P < 0.05). In the 12 mM Gly-treated group, the free Ca2+ in oocytes was not significantly different from that in the Control group but was lower than that in the ABT-199-treated group. Therefore, the addition of 12 mM Gly effectively alleviated the ABT-199-induced increase in free Ca2+ levels in oocytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of Gly on Ca2+ levels in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. (A) The [Ca2+]i in MII porcine oocytes was detected by immunostaining with 5 μM Fluo-3/AM after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. (B) Fluorescence intensity analysis of the Fluo-3AM signal by ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters (a–c) above bars show significant differences (P < 0.05).

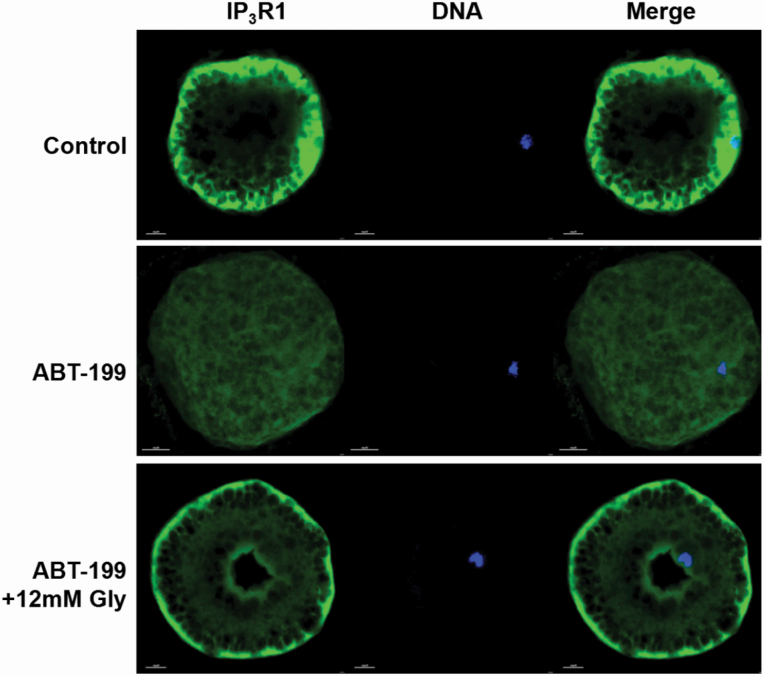

Effect of Gly on IP3R1 cellular distribution in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

We examined whether the inactivation of Bcl-2 might affect IP3R1 localization. A total of 25 oocytes were analyzed in each group. Normally, IP3R1 was distributed in the cortex (Figure 5, Control group). Nevertheless, oocyte maturation in the presence of ABT-199 prevented IP3R1 cortical formation. Here, we show that the mitochondrial damage induced by ABT-199 prevented IP3R1 cortical redistribution, as oocytes that matured in the presence of ABT-199 were devoid of IP3R1 cortical clusters. IP3R1 was evenly distributed in the cytoplasm rather than accumulated in the cortex. After Gly treatment, IP3R1 was redistributed into the cortex after IVM. The frequency of the cortical distribution pattern in the Control and ABT+12 mM Gly groups after IVM was not significant (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of Gly on IP3R1 cellular distribution in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. IP3R1 cellular distribution pattern after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. IP3R1 (green), DNA (blue), and merged images in MII oocytes.

Effect of Gly on apoptosis in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199

We examined Caspase-3 activity and Annexin-V signals in different groups. As shown in Figure 6A, very weak Caspase-3 and Annexin-V fluorescence signals originated in Control and Gly groups oocytes. However, the ABT-199-inhibited oocytes showed clear positive Caspase-3 and Annexin-V signals, indicating the occurrence of apoptosis. The Caspase-3 activities and Annexin-V fluorescence intensity were all higher in the ABT-199 treatment group oocytes than the Control or 12 mM Gly -treated group oocytes (P < 0.05, Figure 6B and C).

Figure 6.

Effect of Gly on apoptosis in porcine oocytes treated with ABT-199. (A) The Caspase-3 activities and Annexin-V signals in MII porcine oocytes after ABT-199 treatment or Gly supplementation. Green, GreenNuc Caspase-3 substrate; Red, Annexin-V-mCherry. Bar = 20 µm. (B) Fluorescence intensity analysis of the Caspase-3 activities by ImageJ software. (C) Fluorescence intensity analysis of the Annexin-V signals by ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different letters (a and b) above bars show significant differences (P < 0.05).

In addition, the mRNA expression of genes associated with apoptosis of mature oocytes was evaluated, as shown in Figure 7B, C. Bax, Caspase-3, and Cyto C were increased, and Bcl-2 was decreased in oocytes treated with ABT-199 compared with the Control group (P < 0.05); after Gly treatment, the mRNA expression of apoptotic genes was ameliorated. These results indicate the protective role of Gly on ABT-199-induced apoptosis.

Discussion

In this study, we explored whether inhibiting Bcl-2 activity affected porcine oocyte maturation and disrupted mitochondrial function, which disturbed the ROS level and increased intracellular calcium levels. In addition, we first investigated the role of Gly in reducing mitochondrial damage induced by exposure to the Bcl-2-specific antagonist ABT-199 during the IVM process of porcine oocytes. We explored the possible causes of porcine oocyte maturation defects after ABT-199 and reported that Gly can reduce the defects induced by ABT-199 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of ABT-199 exposure and Gly treatment on porcine oocytes maturation.

Bcl-2 is a critical control point on mitochondria that regulates apoptosis. Its role in inhibiting Cyto C release from mitochondria has been previously demonstrated. Previous studies have shown that the Bcl-2 inhibitor ABT-199 causes loss of ΔΨm, which actively participates in programmed cell death. PGC-1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Recent reports have suggested that mitochondrial biogenesis is triggered by increased expression of PGC-1α. Our results also showed that ABT-199 decreased the level of ΔΨm and the expression of the mitochondrial-related gene PGC-1α. Notably, after Gly treatment, ΔΨm and the expression of PGC-1α were significantly upregulated. Next, we explored the apoptosis of ABT-199-exposed oocytes. Exposure to the Bcl-2-specific antagonist ABT-199 decreased the expression of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 and increased the expression of the apoptosis-related genes Bax, Caspase-3, and Cyto C. Gly treatment greatly increased the expression of Bcl-2 in oocytes. The results showed that Gly could regulate mitochondrial function and apoptosis, which was similar to our previous results (Li et al., 2018).

To study the role of Gly in mitochondrial damage in the IVM process of porcine oocytes, we investigated the changes in oocyte development after ABT-199 exposure and Gly treatment in the IVM medium. Our results show that Bcl-2 inhibition affects mitochondrial function and has negative effects on cumulus cell expansion and oocyte maturation efficiency. Supplementing Gly in IVM medium improves the meiotic maturation rate and cumulus cell expansion in maturing COCs by regulating mitochondrial function. Our results indicate that Gly administration restored meiotic maturation, mitochondrial function, and apoptosis, indicating that Gly is a potential candidate to improve oocyte maturation in ABT-199-exposed oocytes. Similarly, other studies have reported that Gly protects oocyte mitochondrial homeostasis and improves blastocyst development in mice (Zander-Fox et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2016).

Recent findings indicate that the action of Gly is mediated in part due to its ability to regulate Ca2+ changes. MII oocyte Ca2+ is located throughout the oocyte, and the dynamic change in [Ca2+] i levels regulates the meiosis of oocytes. The imbalance of intracellular calcium homeostasis can not only affect the developmental potential of oocytes but also induce the apoptosis of oocytes (Zhang et al., 2010). Mitochondrial physiology is sensitive to Ca2+ changes, and abnormal increases in Ca2+, even a tiny change, could lead to subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction and oocyte apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2017). The study found that when a high level of Ca2+ carrier was added to the culture medium, it caused cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of rat, pig, and bovine oocytes (Tripathi and Chaube, 2012). The mechanism of apoptosis may be related to mitochondrial dysfunction caused by an imbalance in Ca2+ homeostasis. Indeed, our results showed that [Ca2+] i was increased in oocytes after ABT-199 treatment. When oocytes were matured in the presence of ABT-199, Ca2+ fluorescence intensity was significantly higher than the Control group, indicating interference of ABT-199 on oocyte Ca2+ homeostasis. The higher [Ca2+] i levels in oocytes induced by ABT-199 could be responsible for the low porcine oocyte maturation ability. There have been reports on Bcl-2 inhibition by inducing the mitochondrial stress response, which amplifies the programmed cell death pathway by regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels (Rong et al., 2008, 2009). When Gly was added to IVM medium, the [Ca2+] i level returned to the Control group level. Several studies have shown that the protective effect of Gly is achieved by reducing intracellular Ca2+ overload in many types of cells (Qu et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2014b). These results support the hypothesis that Gly reverses mitochondrial damage caused by ABT-199 and improves the developmental competence of oocytes by regulating [Ca2+]i

The mitochondrial dysfunction induced by Bcl-2 inhibition is associated with oxidative stress. Previous studies demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction can induce an increase in ROS, leading to oxidative stress and damage to cells (Bhatti et al., 2017). Therefore, we detected ROS levels after inhibiting Bcl-2, and the results indicated that ABT-199 treatment caused increased ROS levels and induced oxidative stress in porcine oocytes. In addition, ROS and calcium signals can be mutually regulated; ROS can regulate intracellular Ca2+ levels; and high levels of intracellular Ca2+ are stimulated, leading to increased ROS levels (Gordeeva et al., 2003; Görlach et al., 2015). Our study showed similar results: increased intracellular Ca2+ levels were accompanied by an increase in ROS. Furthermore, the increased ROS and intracellular Ca2+ levels further damage mitochondrial function, resulting in the release of proapoptotic factors, such as Bax, Caspase-3, and Cyto C. Gly is the main component of GSH and can promote the synthesis of GSH in vivo. Several studies have shown that the protective effect of Gly is related to the synthesis of GSH. Our previous study also confirmed that Gly treatment had a beneficial effect on in vitro oocyte maturation and subsequent blastocyst development by decreasing ROS levels to reduce apoptosis. In the present study, we measured the intracellular GSH and ROS levels in MII oocytes, and the results showed that Gly treatment reversed the decrease in GSH levels and increase in ROS levels caused by ABT-199. Studies on other types of cells, such as hepatic parenchymal cells (Qu et al., 2002), endothelial cells (Yamashina et al., 2001), nonneuronal cells (Van den Eynden, 2009), neutrophils, and Kupffer cells (Wheeler et al., 2000), have shown that the cytoprotective effect of Gly is achieved by inhibiting intracellular Ca2+ overload. Our research also demonstrates that Gly blocks the increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels caused by ABT-199.

During oocyte maturation, the capacity of IP3R1s to mediate oocyte Ca2+ release is essential for cellular functions (Fissore, 2019). Recently, antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins were reported to modulate Ca2+ gating of IP3R in the ER, resulting in enhanced cellular bioenergetics and death resistance (Monaco et al., 2013). Targeting the Bcl-2- IP3R interaction induced apoptosis (Rong et al., 2008). To assess whether the increased [Ca2+]i and activated apoptosis in porcine oocytes were influenced by IP3R1, we detected the cellular distribution and localization pattern of IP3R1.Our studies showed that ABT-199 disrupts Ca2+ release by affecting IP3R1 cellular distribution and cortical cluster formation during oocyte maturation. This localization pattern was similar to previous reports in mice (Ito, 2008); however, it is contrary to a study on the localization of IP3R1 in porcine oocytes (Sathanawongs et al., 2015). Whether the reported inability of oocytes matured in the presence of ABT-199 to mount normal [Ca2+]i levels is due to the absence of cortical clusters remains to be determined. The direct interaction between antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and IP3R and the regulation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins on IP3R channel activity have been confirmed by different studies (Chen et al., 2004; Rong et al., 2008). Some studies have reported that Bcl-2 inhibits the activity of IP3R by combining the Bcl-2 homology (BH) 4 domain and IP3R functional regulatory domain, further inhibiting the apoptosis Ca2+ signal mediated by IP3R (Rong et al., 2009; Monaco et al., 2013). However, whether Gly inhibiting apoptosis Ca2+ signaling is related to IP3R1 has not been reported. We examined whether there was a difference in the localization of IP3R1 after Gly treatment in MII pig oocytes. The results showed that Gly restored the cellular distribution and cortical cluster formation of IP3R1 and reversed the impact of ABT-199 on IP3R1. Our findings verified the effects of Gly on IP3R1 cellular distribution in porcine oocytes for the first time. The results also indicated that Gly inhibits the increase of [Ca2+]i induced by ABT-199, which may be related to the regulation of IP3R1 cellular distribution and cortical cluster formation in porcine oocytes.

In summary, our results demonstrate that ABT-199 treatment causes mitochondrial dysfunction and induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in porcine oocytes. Treatment with Gly significantly ameliorates mitochondrial function and apoptosis, and Gly also regulated [Ca2+]i levels and IP3R1 cellular distribution. Collectively, these results show the protective effects of Gly against defects in mitochondrial dysfunction caused by ABT-199 during porcine meiotic oocyte maturation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31902162); Jilin Scientific and Technological Development Programme (20190103149JH). We thank Yifeng Yang, Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences at Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, for his invaluable help with immunofluorescence experiments.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ΔΨm

mitochondrial membrane potential

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular free calcium concentration

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CMF2HC

4-chloromethyl-6.8-difluoro-7-hydroxycoumarin

- COCs

cumulus–oocyte complexes

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- Gly

glycine

- GSH

glutathione

- H2DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- IP3R

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- IP3R1

type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

- IVM

in vitro maturation

- MII

metaphase II

- PGC-1α

PPARγ coactivator-1α

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Antignani, A., and Youle R. J.. . 2006. How do Bax and Bak lead to permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, J. S., Bhatti G. K., and Reddy P. H.. . 2017. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders – a step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 1863(5). doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevini, A. L. T., R. Vassena, C. Francisci, and F. Gandolfi. 2005. Role of adenosine triphosphate, active mitochondria, and microtubules in the acquisition of developmental competence of parthenogenetically activated pig oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 72:1218– 1223. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.038141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.-Y.,, et al. 2016. Glycine increases preimplantation development of mouse oocytes following vitrification at the germinal vesicle stage. Sci. Rep. 6:37262. doi: 10.1038/srep37262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.,, et al. 2004. Bcl-2 functionally interacts with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors to regulate calcium release from the ER in response to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166(2):193–203. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-S1-P135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., C. Glytsou, H. Zhou, S. Narang, D. E. Reyna, A. Lopez, T. Sakellaropoulos, Y. Gong, A. Kloetgen, Y. S. Yap, E. Wang, E. Gavathiotis, A. Tsirigos, R. Tibes, and I. Aifantis. 2019. Targeting mitochondrial structure sensitizes acute myeloid leukemia to venetoclax treatment. Cancer Discov. 9(7):CD-19-0117. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk, J. E., and Green D. R.. . 2008. How do BCL-2 proteins induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization? Trends Cell Biol. 18:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere, J.-P.,, et al. 2011. The IP(3) receptor–mitochondria connection in apoptosis and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fissore, T. W. R. A. 2019. Constitutive IP3R1-mediated Ca2+ release reduces Ca2+ store content and stimulates mitochondrial metabolism in mouse GV oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 132(3):jcs225441. doi: 10.1242/jcs.225441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordeeva, A. V., Zvyagilskaya R. A., and Labas Y. A.. . 2003. Cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and calcium in living cells. Biochemistry (Mosc). 68:1077–1080. doi: 10.1023/A:1026398310003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlach, A., Bertram K., Hudecova S., and Krizanova O.. . 2015. Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 6:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, J. 2008. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 1, a widespread Ca2+ channel, is a novel substrate of polo-like kinase 1 in eggs. Dev. Biol. 320:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I., Xu W., and Reed J. C.. . 2008. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7:1013–1030. doi: 10.1038/nrd2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Q. Guo, Y. M. Wang, Z. Y. Li, J. D. Kang, X. J. Yin, and X. Zheng. 2018. Glycine treatment enhances developmental potential of porcine oocytes and early embryos by inhibiting apoptosis. J. Anim. Sci. 96(6):2427–2437. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi, K., and Mizobe Y.. . 2014. Osmolarity- and stage-dependent effects of glycine on parthenogenetic development of pig oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 60:349–354. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2013-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, G., Vervliet T., and Akl H.. . 2013. The selective BH4-domain biology of Bcl-2-family members: IP3Rs and beyond. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70:1171–1183. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1118-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ola, M. S., Nawaz M., and Ahsan H.. . 2011. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 351:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0709-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W., Ikejima K., Zhong Z., Waalkes M. P., and Thurman R. G.. . 2002. Glycine blocks the increase in intracellular free Ca2+ due to vasoactive mediators in hepatic parenchymal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 283(6):G1249–1256. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00197.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redel, B. K.,, et al. 2016. Glycine supplementation in vitro enhances porcine preimplantation embryo cell number and decreases apoptosis but does not lead to live births. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 83:246–258. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker, R. L. 2012. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in cumulus-oocyte complexes impairs pentraxin-3 secretion, mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and embryo development. Mol. Endocrinol. 26(4):562–73. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Y.-P.,, et al. 2008. Targeting Bcl-2-IP3 receptor interaction to reverse Bcl-2s inhibition of apoptotic calcium signals. Mol. Cell 31:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Y.-P., G. Bultynck, A. S. Aromolaran, F. Zhong, J. B. Parys, H. De Smedt, G. A. Mignery, H. L. Roderick, M. D. Bootman, and C. W. Distelhorst.. 2009. The BH4 domain of Bcl-2 inhibits ER calcium release and apoptosis by binding the regulatory and coupling domain of the IP3 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14397–14402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907555106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathanawongs, A., K. Fujiwara, T. Kato, M. Hirose, M. Kamoshita, R. J. Wojcikiewicz, J. B. Parys, J. Ito, and N. Kashiwazaki. . 2015. The effect of M-phase stage-dependent kinase inhibitors on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 1 (IP3R1) expression and localization in pig oocytes. Anim. Sci. J. 86(2):138–47. doi: 10.1111/asj.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, A., and Chaube S. K.. . 2012. High cytosolic free calcium level signals apoptosis through mitochondria-caspase mediated pathway in rat eggs cultured in vitro. Apoptosis 17(5):439–48. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0702-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eynden, J. 2009. Glycine and glycine receptor signalling in non-neuronal cells. Front Mol. Neurosci. 2:9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.009.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux, D. L. 2011. Apoptogenic factors released from mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813(4):546–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., D. Zhaolai, Z. Wu, G. Lin, S. Jia, S. Hu, S. Dahanayaka, and G. Wu.. 2014a. Glycine is a nutritionally essential amino acid for maximal growth of milk-fed young pigs. Amino Acids 46:2037–2045. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1758-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.,, et al. 2014b. Glycine stimulates protein synthesis and inhibits oxidative stress in pig small intestinal epithelial cells. J. Nutr. 144(10):1540–1548. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.194001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N., H.-S. Hao, C.-Y. Li, Y.-H. Zhao, H.-Y. Wang, C.-L. Yan, W.-H. Du, D. Wang, Y. Liu, Y.-W. Pang, H.-B. Zhu, and X. M. Zhao. . 2017. Calcium ion regulation by BAPTA-AM and ruthenium red improved the fertilisation capacity and developmental ability of vitrified bovine oocytes. Sci. Rep. 7(1):10652. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10907-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, M. D., Stachlewitz R. F., Yamashina S., Ikejima K., and Thurman R. G.. . 2000. Glycine-gated chloride channels in neutrophils attenuate calcium influx and superoxide production. FASEB J. 14:476–484. doi: 10.1078/S0171-9335(04)70024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, P., Rutledge J., and Armstrong D. T.. . 1995. Expression of glycine cleavage system and effect of glycine on in vitro maturation, fertilization and early embryonic development in pigs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 38:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0378-4320(94)01345-M [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashina, S., Konno A., Wheeler M. D., Rusyn I., and Thurman R. G.. . 2001. Endothelial cells contain a glycine-gated chloride channel. Nutr. Cancer 40(2):197–204. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC402_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander-Fox, D., Cashman K. S., and Lane M.. . 2013. The presence of 1 mM glycine in vitrification solutions protects oocyte mitochondrial homeostasis and improves blastocyst development. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 30(1):107–116. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9898-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. X., X. P. Li, S. C. Sun, X. H. Shen, X. S. Cui, and N. H. Kim. 2010. Involvement of ER–calreticulin–Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of porcine oocyte meiotic maturation and maternal gene expression. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 77(5):462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.,, et al. 2017. Enriched endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions result in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in oocytes from obese mice. J. Anim. Biotechnol. 8:62. doi: 10.1186/s40104-017-0195-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]