Abstract

Context.

Cancer prognosis data often come from clinical trials which exclude patients with acute illness.

Objectives.

For patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness hospitalization to 1) describe predictors of 60-day mortality and 2) compare documented decision-making for survivors and decedents.

Methods.

Investigators studied a consecutive prospective cohort of patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness hospitalization. Structured health record and obituary reviews provided data on 60-day mortality (outcome), demographics, health status, and treatment; logistic regression models identified mortality predictors.

Results.

Four hundred ninety-two patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness hospitalization had median age of 60.2 (51% female, 38% minority race/ethnicity); 156 (32%) died within 60 days, and median survival for decedents was 28 days. Nutritional insufficiency (odds rato [OR] 1.83), serum albumin (OR 2.15 per 1.0 g/dL), and hospital days (OR 1.04) were associated with mortality; age, gender, race, cancer, and acute illness type were not predictive.

On admission, 79% of patients had orders indicating Full Code. During 60-day follow-up, 42% of patients discussed goals of care. Documented goals of care discussions were more common for decedents than survivors (70% vs. 28%, P < 0.001), as were orders for do not resuscitate/do not intubate (68% vs. 24%, P < 0.001), stopping cancer-directed therapy (29% vs. 10%, P < 0.001), specialty Palliative Care (79% vs. 44%, P < 0.001), and Hospice (68% vs. 14%, P < 0.001).

Conclusion.

Acute illness hospitalization is a sentinel event in Stage IV cancer. Short-term mortality is high; nutritional decline increases risk. For patients with Stage IV cancer, acute illness hospitalization should trigger goals of care discussions.

Keywords: Stage IV cancer, prognosis, goals of care

Introduction

Palliative care enhances quality of life for patients with Stage IV cancer and aligns treatment with patients’ goals and preferences, thus reducing low-value treatment.1–5 As a result, the Institute of Medicine endorsed palliative care as essential to high-quality cancer care.6,7 In 2016, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) updated practice guidelines to recommend early integration of palliative care for patients with Stage IV cancer.8 ASCO quality measures endorsed by the National Quality Forum promote avoidance of late-life chemotherapy, and earlier Hospice referral-transitions dependent on goals of care decision-making.9

Prognostic awareness is essential for the transition to treatment focused on comfort and quality of life. Yet many patients-particularly those who are older, or who identify as minority race or ethnicity-expect chemotherapy to be curative for Stage IV cancer.10,11 Oncologists use information about prognosis to support timely communication about goals of care.12 Most evidence on cancer prognosis is derived from clinical trials or stage-specific cohorts, and these studies typically exclude patients with poor performance status or co-morbid acute illness.13 While there is a robust body of research on these outpatient populations, these studies do not generalize to the discussion of prognosis for a patient with Stage IV cancer compounded by acute illness requiring hospitalizations.14 Thus, little data are available to support prognostic awareness during the phase of illness when most major goals of care decisions are maded-as Stage IV disease progresses and superimposed acute illnesses become frequent.

To address this gap, we conducted a prospective cohort study of patients with Stage IV cancer who were hospitalized with acute illness to 1) describe predictors of 60-day mortality and 2) compare documented treatment decision-making for survivors and decedents.

Methods

We conducted a consecutive prospective cohort study of patients with Stage IV cancer who were hospitalized with acute illness. All procedures were reviewed by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board, Office of Human Research Ethics, which approved this study for a waiver of full review.

Setting/Subjects

The study site was a 950-bed public teaching hospital affiliated with a National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center. We prospectively identified consecutive patients who (1) had Stage IV cancer, (2) acute illness hospitalization on the Medical Oncology service from 6/2/2017 through 11/15/2018, and (3) were followed by an outpatient oncologist at the study institution defined by at least one appointment before the study period. Patients admitted for scheduled chemotherapy were excluded.

Data Collection and Measures

Data were collected by research staff via structured chart review of the inpatient and outpatient electronic health record (EHR) from hospital admission through 60 days postadmission. To ensure interrater reliability, three reviewers trained on data collection methods, and then abstracted data from the first 20 patients enrolled and compared results five charts at a time, adjudicating any discrepancies, until they achieved 100% interrater reliability. Decisions were logged to support consistent operational definitions of key variables. All data were entered in a structured REDCap database, and reviewers periodically re-assessed interrater reliability to prevent drift in operational definitions of abstracted variables.

Primary Outcome Measure.

The primary outcome was death during 60 days follow-up. Death and date of death were ascertained from EHR review and obituary searches. Obituary searches were conducted for the patient’s home state, including obituaries and funeral home or other notices of death. If there was no evidence of death, the patient was presumed alive. Investigators chose a 60-day time frame as plausible for mortality effects of acute illness superimposed on late-stage cancer.

Patient Characteristics.

Research staff abstracted data on patient age, gender, race and ethnicity, cancer type, acute illness causing hospitalization (categorized as acute medical illness, uncontrolled symptoms, failure to thrive, delirium, or other), and length of hospital stay (days). They measured prehospitalization comorbidities using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; range 0–37; higher scores indicate higher disease burden).15

Nutritional insufficiency was present if within three days of hospitalization, the EHR included diagnoses of failure to thrive, cachexia, malnutrition, or unplanned weight loss, defined as ≥5% of body weight in the last 30 days, ≥7% in the last 90 days, ≥10% in the last 180 days, or qualitative indication of “significant” unplanned weight loss. Research staff recorded serum albumin values if obtained within the first three days.

Documented Decision-Making.

Advance care planning (ACP) was operationalized as presence of a templated ACP note, written advance directives, or Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment directive. Goals of care discussions were present when a clinician documented communication with a patient or patient’s surrogate that included two key elements-1) discussion of prognosis or health status and 2) shared decision-making about broad goals or specific major treatment choices. For example, documented discussion of prognosis or health status could include information-sharing about cancer incurability, disease progression despite treatment, or life expectancy. Documented shared decision-making could include discussion of a choice between goals such as comfort or survival or discussion of specific treatment options such as stopping or continuing cancer-directed treatment.

Research staff collected additional descriptive data about treatment decisions. Specific treatment decisions included resuscitation orders, cancer-directed treatment, and hospice. They also described treatment plans as curative, primarily cancer-directed, mix of palliative and cancer-directed, or palliative.

Measures of Treatment Use.

Staff recorded treatment for pain or dyspnea. Access to specialty Palliative Care and Hospice was present when the EHR included encounters with specialty Palliative Care in hospital or clinic, or when a Hospice referral was made. Researchers also recorded intensive care unit use and cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts.

Analysis

Investigators described all variables in bivariate statistics, dichotomized by survivors and decedents at 60 days. Two-sample t-tests were used for continuous variables, and Chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables to test differences between survivors and decedents. Dates of death within the 60-day follow-up period were used to generate a Kaplan-Meier survival curve. To understand factors associated with 60-day survival vs. death, investigators ran multivariable logistic regression models with mortality as the dependent variable. Based on a conceptual framework from a review of factors that may be associated with mortality, multivariable models included age, gender, race, CCI (continuous), length of initial hospital stay (continuous), nutritional insufficiency (binary), and albumin value from the first three days of hospitalization; missing albumin values were imputed to the median. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval and P-values based on Wald Chi-squared tests were reported to justify the statistical significance. A P-value smaller than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patients With Stage IV Cancer and Acute Illness Hospitalization

During the 18.5 month study period, 492 patients with Stage IV cancer were hospitalized with acute illness (Table 1). Patients’ average age was 60.2 years, 51% were female and 38% identified as minority race or ethnicity. Cancer types were gastrointestinal (23%), genitourinary (19%), breast (18%), and lung (16%). Acute illness hospitalization was caused by infection or thromboembolic disease (54%) or uncontrolled cancer-related symptoms (34%). Patients had moderate levels of co-morbidity (CCI mean score 6.9, range 2–15) and nutritional insufficiency present for 46%. Patients were hospitalized an average of 5.2 days, and 33% were re-admitted during 60-day follow-up (0.53 hospitalizations per 60 person-days at risk).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Stage IV Cancer and Acute Illness Hospitalization

| Characteristic | Total n = 492 | Survivors n = 336 | Decedents n = 156 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 60.2 (21–93) | 59.6 (21–93) | 61.6 (22–90) | 0.112 |

| Female gender | 252 (51%) | 175 (52%) | 77 (49%) | 0.574 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 303 (62%) | 209 (63%) | 94 (61%) | 0.763 |

| Black | 143 (29%) | 96 (29%) | 47 (30%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 23 (5%) | 15 (5%) | 8 (5%) | |

| Asian | 9 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Other | 8 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (3%) | |

| Primary cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Gastrointestinal | 112 (23%) | 67 (20%) | 45 (29%) | 0.108 |

| Genitourinary | 91 (19%) | 62 (18%) | 29 (19%) | |

| Breast | 87 (18%) | 60 (18%) | 27 (17%) | |

| Lung | 80 (16%) | 53 (16%) | 27 (17%) | |

| Head and Neck | 53 (11%) | 42 (13%) | 11 (7%) | |

| Melanoma | 33 (7%) | 27 (8%) | 6 (4%) | |

| Neuro | 13 (3%) | 11 (3%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Other | 23 (5%) | 14 (4%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Primary reason for hospitalization | ||||

| Acute medical illness | 267 (54%) | 183 (54%) | 84 (54%) | 0.097 |

| Uncontrolled symptoms | 168 (34%) | 119 (35%) | 49 (31%) | |

| Failure to thrive | 35 (7%) | 17 (5%) | 18 (12%) | |

| Acute confusion/delirium | 21 (4%) | 16 (5%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Comorbidity (CCI) a, mean (range) | 6.9 (2–15) | 6.8 (2–15) | 7.1 (2–13) | 0.036 |

| Nutritional insufficiency diagnosed within three days of hospitalization | 226 (46%) | 135 (40%) | 91 (58%) | <0.001 |

| Malnutrition | 171 (35%) | 98 (29%) | 73 (47%) | <0.001 |

| Unplanned weight loss | 155 (32%) | 95 (28%) | 60 (38%) | 0.024 |

| Failure to thrive | 60 (12%) | 28 (8%) | 32 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Cachexia | 40 (8%) | 18 (5%) | 22 (14%) | 0.001 |

| Serum albumin level within three days of hospitalizationb, mean g/dL (range)c | 3.2 (1.2–5.4) | 3.3 (1.7–5.4) | 3.0 (1.2–4.5) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay, days mean (range) | 5.2 (0–57) | 4.6 (0–57) | 6.5 (1–48) | 0.002 |

| Deaths | 156 (32%) | |||

| Survival, days median (range) | 28 (3–60) | |||

CCI= Charleson Comorbidity Index; range 0–37; higher scores indicate higher disease burden.

Missing for 14% of patients.

A normal albumin range is 3.4 to 5.4 g per deciliter (g/dL).

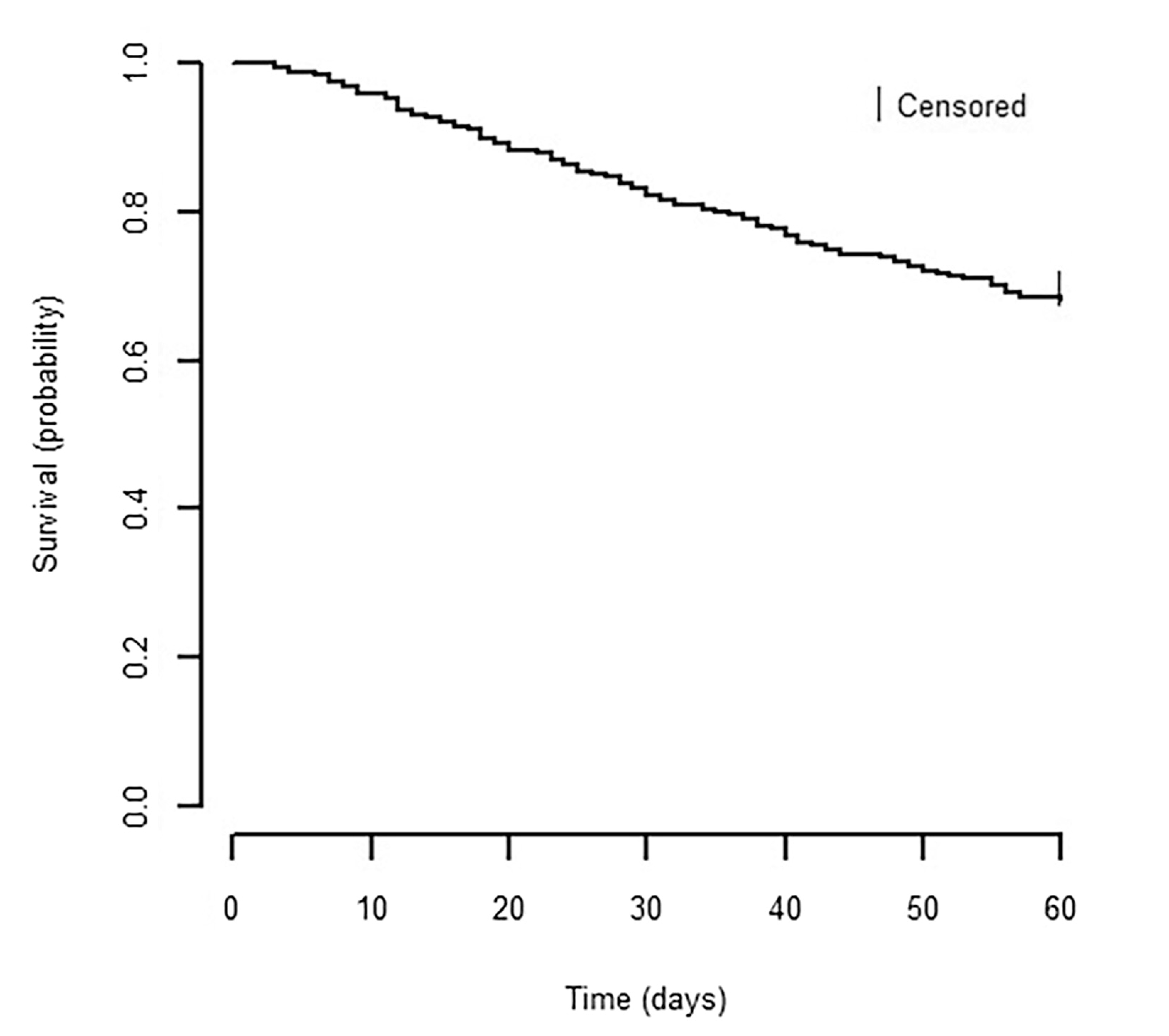

60-Day Mortality

Within 60 days of hospital admission, 32% (n = 156) of patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness died. Decedents lived a median of 28 days (range 3–60) after admission; deaths occurred throughout the follow-up period, and only 16 deaths occurred during initial hospitalization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness hospitalization. Probability of survival calculated from first day of hospital admission through 60 days postadmission. Number of patients at risk at indicated time points are shown below the x-axis.

Predictors of 60-Day Mortality

In bivariate comparisons, decedents had higher rates of co-morbidity (CCI 7.1 vs. 6.8, P = 0.036), nutritional insufficiency (58% vs. 40%, P < 0.001), lower serum albumin (3.0 vs. 3.3 g/dL, P < 0.001), and longer lengths of hospital stay (6.5 vs. 4.6 days, P = 0.002) (Table 1). Survivors and decedents showed no significant differences in age, gender, race/ ethnicity, primary cancer type, or reason for hospitalization.

In the multivariable model of 60-day mortality (Table 2), nutritional insufficiency was associated with twice the odds of 60-day mortality (40% vs. 58%, adjusted OR 1.83, P = 0.002). Each added day in initial hospital length of stay was marginally associated with mortality (OR 1.04, P = 0.012). A decrease in albumin of 1.0 g/dL was associated with a doubling of the odds of mortality (OR 2.15, P < 0.001). Age, gender, race/ethnicity, and co-morbidity were not predictive.

Table 2.

Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Stage 4 Solid-Tumor Cancer

| Variable | Coefficient (95% Confidence Interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome: mortality | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.538 |

| Female gender | 0.96 (0.64, 1.45) | 0.860 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black | 1.05 (0.66, 1.64) | 0.850 |

| Other | 1.46 (0.70, 3.07) | 0.313 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.29) | 0.119 |

| Nutritional Insufficiencya | 1.83 (1.22, 2.74) | 0.004 |

| Lower Albumin value (per 1.0 g/dL) | 2.15 (1.49, 3.12) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (per day) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 0.013 |

Nutritional insufficiency was defined as a diagnosis of any of the following within three days of hospital admission: failure to thrive, cachexia, malnutrition, or unplanned weight loss.

Documented Treatment Decision-Making

Clinicians documented goals of care discussions for 42% (Table 3). When prognosis was addressed, qualitative terms such as incurable and progressive were typical (32%). Prognosis of less than 6 months was noted for 26% of decedents. Documented goals of care discussions were more common for decedents than for survivors (70% vs. 28%, P < 0.001), as was any ACP (72% vs. 51%, P < 0.001). Goals of care discussions were usually in hospital, led by Palliative Care or inpatient oncology clinicians.

Table 3.

Patient Decision-Making and Treatment Use During 60-Day Follow-Up

| Decision-Making | Total n = 492 | Survivors n = 336 | Decedents n = 156 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician documented prognosis | ||||

| Not documented | 266 (54%) | 224 (67%) | 42 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Time frame estimated | 66 (14%) | 24 (7%) | 42 (27%) | |

| Incurable/progressive, no time frame | 157 (32%) | 86 (26%) | 71 (46%) | |

| Documented goals of care discussion | 206 (42%) | 96 (29%) | 110 (71%) | <0.001 |

| Two or more goals of care discussions | 95 (19%) | 40 (12%) | 55 (35%) | <0.001 |

| Any documented advance care planning | 285 (58%) | 173 (51%) | 112 (72%) | <0.001 |

| Setting of first goals of care discussion | ||||

| Initial hospitalization | 114 (23%) | 39 (12%) | 75 (48%) | <0.001 |

| Subsequent hospitalization/ED visit | 48 (10%) | 22 (7%) | 26 (17%) | |

| Outpatient setting | 44 (9%) | 35 (10%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Final code status | ||||

| Full | 295 (60%) | 247 (74%) | 48 (31%) | <0.001 |

| Limited | 8 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| DNR/DNI | 189 (38%) | 82 (24%) | 107 (68%) | |

| Initial treatment plan | ||||

| Curative | 6 (1%) | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.008 |

| Primarily cancer-directed | 390 (79%) | 276 (82%) | 114 (73%) | |

| Mix of palliative and cancer-directed | 95 (19%) | 54 (16%) | 41 (26%) | |

| Primarily palliative | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Final treatment plan | ||||

| Curative | 5 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Primarily cancer-directed | 239 (49%) | 221 (66%) | 20 (12%) | |

| Mix of palliative and cancer-directed | 100 (20%) | 74 (22%) | 26 (17%) | |

| Primarily palliative | 148 (30%) | 36 (11%) | 114 (72%) | |

| Decision-making cancer-directed therapy | ||||

| Decision to stop therapy | 81 (16%) | 35 (10%) | 46 (29%) | <0.001 |

| Decision to use therapy | 302 (61%) | 266 (79%) | 36 (23%) | |

| Not a treatment option | 18 (4%) | 9 (3%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Discussed but no decision | 82 (17%) | 21 (6%) | 61 (39%) | |

| Not discussed | 9 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (3%) | |

| ICU Transfer (% yes) | 61 (12%) | 27 (8%) | 34 (22%) | <0.001 |

| CPR attempted (% yes) | 5 (1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (3%) | 0.020 |

| Specialty PC Services | 270 (55%) | 147 (44%) | 123 (79%) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient PC | 157 (32%) | 78 (23%) | 79 (51%) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient palliative care | 97 (20%) | 79 (24%) | 18 (12%) | 0.002 |

| Hospice referral | 138 (28%) | 44 (13%) | 94 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Time to Hospice | 18.8 (1–61) | 27.4 (1–61) | 14.8 (1–51) | <0.001 |

ED = emergency department; DNR = do not resuscitate; DNI = do not intubate; ICU = intensive care unit; PC = palliative care; CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

At the time of hospital admission 79% of patients with Stage IV cancer had orders for Full Code status, and this did not differ for the survivor and decedent groups. However, during the 60-day follow-up period treatment orders for these groups differed, indicating a growing awareness of prognosis. Compared with patients who lived 60 days, patients who died were more likely to have do not resuscitate/do not intubate orders (68% vs. 24%, P < 0.001), transition to a palliative treatment plan (72% vs. 11%, P < 0.001), document stopping cancer-directed therapy (29% vs. 10%, P < 0.001), and elect Hospice (68% vs. 14%, P < 0.001). More decedents spent time in intensive care (22% vs. 8%, P < 0.001), accessed specialty Palliative Care services (79% vs. 44%, P < 0.001), and enrolled in Hospice (60% vs. 13%, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Acute illness hospitalization is a sentinel event for persons with Stage IV cancer. In this cohort of 492 patients with Stage IV cancer and acute illness hospitalization, 32% died within 60 days of admission. Though we anticipated mortality would peak during and just after acute illness hospitalization, we found a median survival of 28 days with most deaths occurring after discharge. This study addresses an important gap in prognostic information for patients with Stage IV cancer, because most research fails to address the effect of acute illness superimposed on chronic serious illness from cancer. Clinicians understand that a patient with advanced cancer and pneumonia is more seriously ill than a patient with advanced cancer alone, yet often treat the pneumonia as fully reversible rather than consider it as a complication of complex serious illness causing weakened immunity to infection. Because specialty palliative care teams continue to be more available in hospital than outpatient settings, our findings may encourage oncologists to consider referral.

Our findings are comparable to three other single site studies of prognosis for patients with cancer and acute illness hospitalization. Investigators at the University of Wisconsin studied all patients with solid organ cancer of any stage (87% had Stage IV disease) and acute illness hospitalization during a 3-month period in 2010. Patients had a median survival of 3.4 months, and one-third of patients died within 60 days.16 Investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital studied a prospective cohort of patients with advanced incurable cancer (n = 932) and acute hospitalizations; they reported a 90-day mortality rate of 43.1%, yet only 9.4% were discharged with hospice services.17,18 Finally, investigators at MD Anderson Center examined mortality for patients with Stage IV breast cancer and acute illness hospitalization and reported 40% (50/123 patients) died in hospital or within 14 days of discharge.19 Taken together, acute illness hospitalizations for patients with Stage IV cancer indicate a 20–40% risk of near-term mortality.

Given significant mortality risk, acute illness hospitalizations for patients with Stage IV cancer should trigger discussion of goals of care. This conclusion matches a recent prognostic study in which clinicians strongly endorsed goals of care discussions for cancer with a 30% risk of death within 6 months.20 When discussions are led with skill and compassion, they help patients and families develop prognostic awareness and prepare emotionally, spiritually, and practically for death.21 Goals of care discussions also support informed treatment decisions and goal-concordant care. While some patients may continue to prioritize life prolongation above other goals, others may prioritize comfort and quality of life. Prognostic awareness is essential to allow patients who prioritize these goals to choose a more palliative treatment plan. Earlier goals of care decision-making is encouraged by the Institute of Medicine and ASCO.6–8

One implication is a need for collaboration in the care of patients with Stage IV cancer. Evidence supports outpatient Palliative Care for patients with advanced stage disease and high symptom burden; this setting also facilitates collaboration with the primary Oncologist.2–4,22 However, hospitalizations become more common as Stage IV cancer is accompanied by nutritional decline and acute illness complications. In a prior quality improvement study, we found that when patients with Stage IV cancer experienced unplanned admissions, referral to Palliative Care resulted in increased frequency of goals of care discussions.23 A comprehensive model of early integrated oncology palliative care may be most effective if services are coordinated between outpatient and inpatient settings.24,25 Furthermore, any effective model must be efficient and minimize redundancy, given workforce shortages in Oncology and Palliative Care.26

As with any research, this study should be interpreted while taking into account the strengths and limitations of its design. Strengths include prospective and consecutive enrollment of a large cohort of patients; one limitation is that data are from a single center with a comprehensive cancer center and well-integrated palliative care. Evidence from more diverse settings would be needed to generalize the results. A second limitation is that ascertainment of death through EHR and obituary review may result in some underestimation. A third limitation is the lack of consistent EHR data on performance status, a variable likely to be predictive of mortality. Purposeful inclusion of performance status in future EHR builds could improve prognostication and attention to patients’ supportive care needs. Finally, data on goals of care discussions and decision-making is constrained to what clinicians decide to document. While documented decision-making is critical because other clinicians use it to guide treatment, patient interviews would yield another perspective. Clinicians likely document discussions more often when treatment goals change and thus our estimate may underrepresent the true frequency of such communication.

In conclusion, this cohort study found that one-third of patients with Stage IV cancer and hospitalization with acute illness died within 60 days of admission. Evidence from this study may be helpful to improve the frequency and timing of goals of care discussions in cancer care. Current evidence shows opportunities to improve communication about prognosis, goals of care, and treatment decision-making for this patient population. Acute illness hospitalizations may make prognosis more clear to clinicians and patients and should trigger enhanced goals of care communication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose with regard to this project and article. The authors alone are responsible for the conceptualization, execution, and/or drafting of this project and article.

Contributor Information

Laura C. Hanson, Division of Geriatric Medicine & Palliative Care Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Natalie C. Ernecoff, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Kathryn L. Wessell, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Feng-Chang Lin, Department of Biostatistics, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Matthew I. Milowsky, Division of Hematology and Oncology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Frances A. Collichio, Division of Hematology and Oncology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

William A. Wood, Division of Hematology and Oncology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Donald L. Rosenstein, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

References

- 1.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316: 2104–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh RB, Kirch RA, Smith TJ, Temel JS. Early specialty palliative careetranslating data in oncology into practice. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2347–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, Spence C, Iwasaki K. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrell BR, Smith TJ, Levit L, Balogh E. Improving the quality of cancer care: implications for palliative care. J Palliat Med 2014;17:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ASCO Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Reporting Registry. Available from https://practice.asco.org/sites/default/files/drupalfiles/QCDR-2019-Measure-Summary.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 10.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennes IT, Temel JS, Hoedt C, Meilleur A, Lamont EB. Predictors of newly diagnosed cancer patients’ understanding of the goals of their care at initiation of chemotherapy. Cancer 2013;119:691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan M, Temel JS, Wright AA, Bernacki R, Selvaggi K, Balboni T. Predicting life expectancy in patients with advanced incurable cancer: a review. J Support Oncol 2013;11:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109:djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salpeter SR, Malter DS, Luo EJ, Lin AY, Stuart B. Systematic review of cancer presentations with a median survival of six months or less. J Palliat Med 2012;15:175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J chronic Dis 1987;40: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocque GB, Barnett AE, Illig LC, et al. Inpatient hospitalization of oncology patients: are we missing an opportunity for end-of-life care? J Oncol Pract 2013;9:51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Moran SM, et al. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2017;123:4720–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lage DE, Nipp RD, D’Arpino SM, et al. Predictors of Posthospital transitions of care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin JA, Parkes A, El-Jawahri A, et al. Retrospective evaluation of palliative care and hospice utilization in hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer. Palliat Med 2016;30:854–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh RB, Manz C, Chivers C, et al. Machine learning approaches to predict 6-month mortality among patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1915997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Back AL. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med 2013;16: 894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas TH, Jackson VA, Carlson H, et al. Communication differences between oncologists and palliative care clinicians: a qualitative analysis of early, integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2019;22: 41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson LC, Collichio F, Bernard SA, et al. Integrating palliative and oncology care for patients with advanced cancer: a quality improvement intervention. J Palliat Med 2017; 20:1366–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e588–e653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015; 13:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]