Abstract

To estimate the impact on emergency attendance for stroke and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the pandemic of COVID-19 in Beijing, China. Based on 17,123 and 8693 emergency attendance for stroke and AMI, an interrupted time-series (ITS) study was conducted. Since 01/24/2020, the top two levels of regulations on major public health have been implemented in Beijing. This study covered from 03/01/2018 to 06/03/2020, including 19 weeks of lockdown period and 99 weeks before. A segmented Poisson regression model was used to estimate the immediate change and the monthly change in the secular trend of the emergency attendance rates. The emergency attendance rates of stroke and AMI cut in half at the beginning of the lockdown period, with 52.1% (95% CI 45.8% to 57.7%) and 63.1% (95% CI 56.1% to 63.1%) immediate decreases for stroke and AMI, respectively. Then during the lockdown period, 7.0% (95% CI 2.5%, 11.6%) and 16.1% (95% CI 9.5, 23.1) increases per month in the secular trends of emergency attendance rates were shown for stroke and AMI, respectively. Though the accelerated increasing rates, there were estimated 1335 and 747 patients with stroke and AMI without seeking emergency medical aid during the lockdown, respectively. The emergency attendance for stroke and AMI cut in half at the beginning of the pandemic then had gradual restoration thereafter. The results hint the need for more engagement and communications with all stakeholders to reduce the negative impact on CVD emergency medical services during the crisis.

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11239-021-02385-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Emergency attendance, Stroke, Acute myocardial infarction, Pandemic, COVID-19

Highlights

The impact on emergency attendance for stroke and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the pandemic of COVID-19 remains to be evaluated.

The emergency attendance for stroke and AMI cut in half at the beginning of the pandemic then had gradual restoration thereafter.

Though the gradual restoration, there were estimated 1335 and 747 patients with stroke and AMI without seeking for emergency medical aid during the pandemic in Beijing.

More engagement and communications with all stakeholders are needed to reduce the negative impact on cardiovascular emergency medical services during the crisis.

Introduction

The pandemic of coronavirus disease in 2019 (COVID-19) spread over 200 countries is still ongoing [1]. It has caused a major crisis to the whole health care system, which has been reorganized to cope with the enormous increase of critically ill patients. In the meantime, hospital attendance for cardiovascular conditions was reported to have decreased precipitously. Reports from Spain, Italy, France, the US, and China showed a reduction of 10% to 70% in hospital admission for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [2–8], though the COVID-19 may probably increase CVD risks as a result of endothelial injury, hypercoagulable status, and systemic inflammatory [9–11]. Most of these reports described the changes at an early stage of this crisis by comparing the admissions in the pandemic with the parallel period during the previous year, without considering the secular trend, meteorological, and other confounders in CVD hospital admissions. According to previous reports, temporal trends existed in the rates of hospital admissions for CVD, especially in developing countries, the hospital admission for CVD continued increasing [12–15]. Besides, meteorological and air pollution factors also affect CVD hospital attendance [16–18]. Therefore, the actual reduction in the hospital admissions for CVD needs to be estimated more precisely during the pandemic, with considering these confounders.

In China, the outbreak of COVID-19 spread rapidly at the beginning of this year. Rapid and strict regulations were implemented to contain the spread [19]. The government launched the first-level response to major public health from January to April in 30 provinces and launched the second-level response thereafter until the beginning of June. Due to the aggressive measures, the outbreak has been slowed down [20]. On the other hand, series guidelines were released to deliver uninterrupted effective care for stroke and AMI during the pandemic [21–23]. Based on a relatively complete lockdown period, in this study, we aimed to estimate the impact on the emergency attendance for stroke and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Beijing, not only the immediate changes at the beginning of the pandemic but also the secular change during the pandemic, accounting for the temporal trend, meteorological, air pollution, and other confounders. The results will provide information on the influence on emergency medical services for CVD during the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

An interrupted time-series (ITS) design was used to estimate the changes in the emergency attendance for stroke and AMI during the whole lockdown period. ITS is valuable for evaluating population-level health interventions over a clearly defined time [24–26]. Based on the design, a time series of emergency admissions rates with the underlying trend before the lockdown period was first estimated. Then, under the hypothetical scenario without the pandemic and regulations, the admission rates were further predicted and were used to compare with the actual rates during the lockdown period. Aggressive disease control measures according to the top two levels of responses to major public health in Beijing lasted from January 24th to early June. The observational period in this study covered 118 weeks from 03/01/2018 to 06/03/2020, including 19 weeks of lockdown period and 99 weeks before. Variables that may influence the attendance besides the pandemic regulations were also accounted for, including the secular trend, seasonality, meteorological factors [27], air pollution [28], and the number of public holidays.

Data collection

The daily number of emergency attendance for stroke and AMI was obtained from the Beijing Emergency Care Database. This database was constructed from 2018 to connect the emergency medical services (EMS) system and the emergency departments in all secondary and tertiary hospitals in Beijing, keeping track of all the records for stroke and AMI in emergency departments, which covered all the residents (about 20 million) in Beijing. The main variables in this database include symptoms at disease onset, hospital arrival time, hospital information, workflows during the treatment, disease diagnosis at discharge, and so on. In this study, stroke was defined as a primary diagnosis of ICD-10 (international classification of disease, 10th version) code I60-I64 at discharge, and AMI was defined as a primary diagnosis of ICD-10 code of I21 at discharge. To be noted, stroke patients obtained from the database during the pandemic were all not infected with COVID-19, as all the COVID-19 cases were strictly quarantined and treated in the designated hospitals.

The daily average temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%) were collected from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System (http://data.cma.cn/). The daily particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5) concentrations (µg/m3) was collected from Beijing Municipal Ecology and Environment Bureau (http://sthjj.beijing.gov.cn/). Data of all sentinel monitoring stations around Beijing were averaged for daily average temperature, relative humidity, and PM2.5 concentrations. The Chinese public holidays (New Year’s Day, Spring Festival, Qingming Festival, Labor Day, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-autumn Festival, National Day) were released by the General Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China (http://english.www.gov.cn).

Statistical analysis

The emergency attendance rates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for stroke and AMI were first calculated and reported as age- and sex- standardized rates using the residents in the sixth demographic census in Beijing. Then using the ITS design, a segmented Poisson regression model was developed to test whether the emergency attendance rate changed at the beginning and during the lockdown period [29]. All the variables were set up on a weekly basis. The response variable was the weekly number of stroke or AMI emergency department admissions. The population size for the permanent residents from the sixth demographic census in Beijing was included as an offset variable. A binary variable was included in the model, with the value of 1 indicating the lockdown period and 0 before. A linear predictor for the time was included in the model to quantify the underline secular trends. A Fourier series of sine and cosine terms of time was also modeled and included in the model accounting for the seasonality [24]. The number of public holidays in each week, the mean temperature, relative humidity, and PM2.5 concentrations were was also adjusted as penalized splines with the degree of freedom of 4. The immediate decreases and the monthly changes in the secular trend of emergency attendance rates were calculated by the coefficient of the binary indicator of the lockdown period and its interaction term with time, respectively. The absolute number of reduced emergency attendance was calculated using the actual attendance and the predicted number without the pandemic and the regulations.

The analyses were stratified by different age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years), sex (females and males), and disease subtypes (stroke: ischemic stroke (IS) and hemorrhagic stroke (HS); AMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and un-STEMI). The heterogeneity of changes between subgroups was tested by Cochran's Q-test. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by including a spline-based smooth temporal trend in the model to capture a nonlinear temporal trend. All analyses were conducted in R (V.3.6.3) [30].

Results

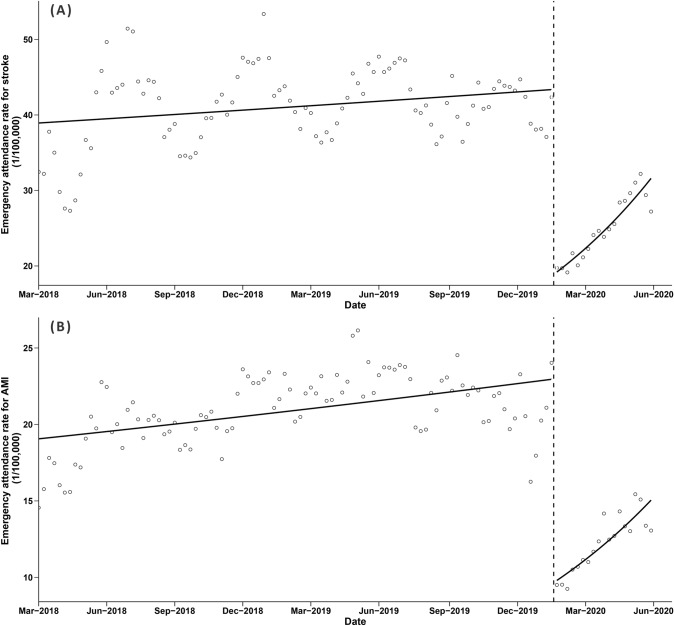

During the observational period, there were 17,123 and 8,693 emergency attendance for stroke and AMI in Beijing, respectively. The annual emergency attendance rates (1/100,000) for stroke and AMI were 40.3 (95% CI 39.4, 41.2), and 20.5 (95% CI 19.8, 21.1), respectively. More attendance occurred in males and those aged ≥ 65 years for both conditions (Table 1). Increasing secular trends were observed for both conditions before and during the lockdown period (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Annual emergency attendance rate for stroke and AMI in Beijing from Mar. 2018 to Jun. 2020

| Stroke | AMI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of attendance | Annual attendance rate (1/100,000, 95% CI) | Number of attendance | Annual attendance rate (1/100,000, 95% CI) | |

| Overall | 17,123 | 40.3 (39.4, 41.2) | 8693 | 20.5 (19.8, 21.1) |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 years | 8277 | 21.3 (20.7, 22.0) | 5428 | 14.0 (13.5, 14.6) |

| ≥ 65 years | 8845 | 238.9 (231.6, 246.3) | 3262 | 88.1 (83.7, 92.7) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 5514 | 26.8 (25.8, 27.9) | 1864 | 9.1 (8.5, 9.7) |

| Male | 11,609 | 52.9 (51.5, 54.3) | 6829 | 31.1 (30.0, 32.2) |

AMI acute myocardial infarction

Fig. 1.

Emergency attendance rate for stroke and AMI before and after the lockdown period from Mar. 2018 to Jun. 2020. AMI acute myocardial infarction. Vertical dashed line: Jan 24th, 2020, when the lockdown period began. Solid lines: time trend. Hollow dots: emergency attendance rates. Panel a: stroke. Panel b: AMI

Changes in emergency attendance rate

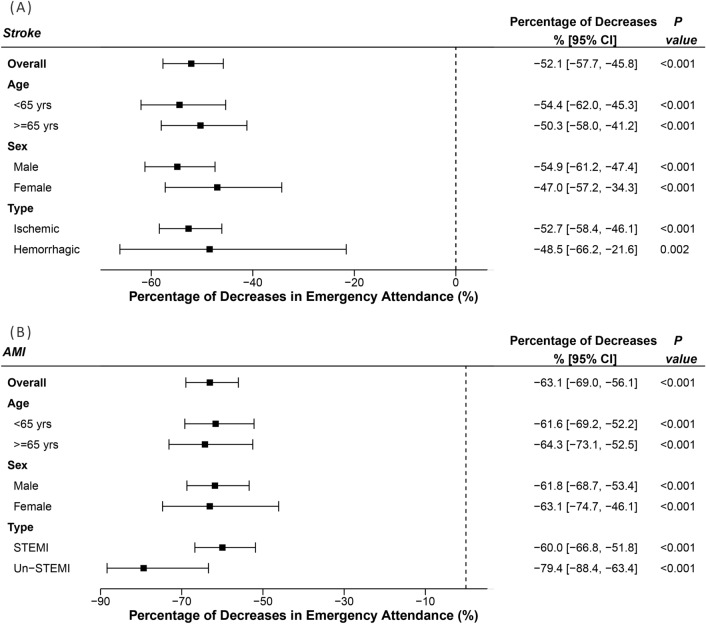

Remarkable immediate decreases in emergency attendance rates of these two conditions were seen at the point when the lockdown period began (Fig. 1). It was estimated that there were 52.1% (95% CI 45.8% to 57.7%) and 63.1% (95% CI 56.1% to 63.1%) immediate decreases in the emergency attendance rates for stroke and AMI, respectively (both P < 0.001, Figs. 1, 2). The decreases in different age and sex subgroups were similar, for both stroke and AMI (all P > 0.05, Fig. 2). For different disease types, there were similar decreases in IS compared with HS, while there were about 20% more decreases in un-STEMI compared with STEMI, though the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.528). The results in the sensitivity analysis didn’t change much (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Immediate decreases in emergency attendance rates of stroke and AMI at the beginning of the lockdown period. AMI acute myocardial infarction. Panel a: stroke. Panel b: AMI

During the lockdown period, significant increases were observed in the secular trends compared with the pre-lockdown period. There were 7.0% (95% CI 2.5%, 11.6%) and 16.1% (95% CI 9.5, 23.1) increases per month in the secular trends of emergency attendance rates for stroke and AMI, respectively. The secular changes in all different subgroups were similar (all P > 0.05, Table 2). Results from sensitivity analysis didn’t change much (Table S2).

Table 2.

Monthly increases in secular trends of emergency attendance rates for stroke and AMI during the lockdown period

| Stroke | AMI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly secular increases (95% CI) | P-value | Monthly secular increases (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Overall | 7.0 (2.5, 11.6) | 0.002 | 16.1 (9.5, 23.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 years | 10.6 (4.0, 17.7) | 0.001 | 13.9 (5.9, 22.5) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 65 years | 4.2 (− 1.6, 10.5) | 0.161 | 18.9 (8.0, 30.9) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2.9 (− 4.2, 10.5) | 0.439 | 28.2 (12.5, 46.2) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 9.4 (3.8, 15.2) | 0.001 | 12.9 (5.7, 20.6) | < 0.001 |

AMI acute myocardial infarction

Reductions in the number of emergency attendance

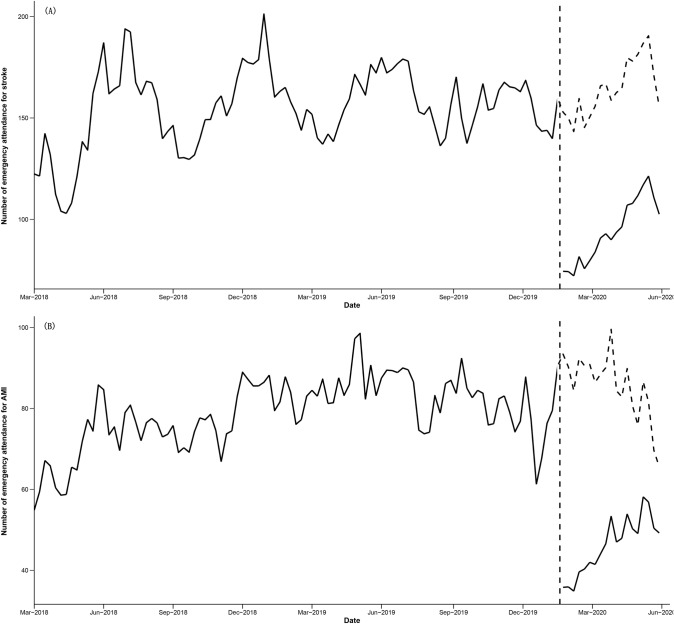

There would have much more emergency attendance for stroke and AMI without the pandemic and regulations (the dashed lines compared with the solid lines in Fig. 3). It was estimated that there were 1,335 and 747 patients with stroke and AMI didn’t seek emergency medical aid during the lockdown period, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Reductions in the number of emergency attendance for stroke and AMI during the lockdown period. AMI acute myocardial infarction. Vertical dashed line: Jan 24th, 2020, when the lockdown period began. Solid lines: actual number of emergency attendance. Dashed lines: counterfactual number of emergency attendance without the pandemic. Panel a: stroke. Panel b: AMI

Discussions

Based on the records from the EMS system and the emergency department of all secondary and tertiary hospitals in Beijing, we found that the emergency attendance rates for stroke and AMI decreased by more than a half at the beginning of the pandemic. Several reasons may contribute to the decreased utilization of healthcare services. One important reason may be the concerns from patients and their families about the in-hospital cross-infection of COVID-19 [3]. Besides, during the lockdown period with strict regulations for social distancing, people were encouraged to postponed un-urgent medical procedures. Thus, because of a lack of medical knowledge, patients with mild to moderate symptoms may prefer to choose not to go to the hospital. Another reason for the decrease may be that the change of lifestyle in the lockdown period may reduce the risk of these two conditions, such as better medication adherence. Reductions in hospital admissions for CVD during the pandemic were reported in different countries with varying degrees from 10 to 70% [3–8, 31]. However, data from the UK didn’t show significant changes in emergency ambulance services for stroke and heart attack [32]. The differences between studies come from the disparities in study designs, the local infection rate of COVID-19, the local regulations to contain the pandemic, the public attitude to the pandemic, and so on.

The results showed consistent immediate decreases in different age and sex subgroups. For different disease types, there were similar decreases in IS and HS, while about 20% more decreases occurred in un-STEMI than STEMI, though the difference was not significant. We don’t know the exact reasons for the differences. Further studies are needed to test the hypothesis of whether there were consistent decreases in different disease types and seek for possible reasons. Due to the sharp immediate decreases, the decreases may not be only restricted to those with mild symptoms, but also may exist in patients with different severities of symptoms.

According to the results, significant increases were observed in the secular trends of rates during the lockdown compared with the pre-lockdown period. There were 7.0% and 16.1% increases per month for stroke and AMI, respectively, indicating gradual restoration in the CVD emergency medical services. The incidence of stroke and AMI would not diminish during the pandemic and effective rapid medical care for these two life-threatening conditions is paramount to gain maximal functional recovery. To deliver timely and effective care for stroke and AMI, series guidelines for stroke and AMI hyperacute management during the pandemic were recommended [21–23, 33, 34]. Physicians from different hospitals continue to share treatment experiences [1, 22, 23, 35, 36]. Partly due to these efforts, gradual restoration in the CVD emergency medical services showed in the results. Most importantly, the infectious rate of COVID-19 in the study population decreased steadily and was under control [20]. Medical services as well as other social activities had recovery gradually. The public attitude changed as the pandemic prolonged and the probability of patients going to hospital continue increasing. Despite these improvements, the sharp immediate decreases when the pandemic began should make an alert to both medical and patent organizations emphasizing the need for acute medical services for conditions, especially for life-threatening conditions, even in this special lockdown period. Educations on the importance of rapid therapy for stroke and AMI in the general population, especially in high-risk populations, should be strengthened. As the pandemic is continuing, an enhanced effort by all the stakeholders is needed to maintain the order of the medical service together.

Even with the increases in the secular trend, there were absolute reductions for the number of emergency attendance, that there were 1000 and 800 patients with stroke and AMI didn’t seek emergency medical services during the pandemic. For stroke and AMI, even patients with mild symptoms will benefit a lot from timely treatment. Therefore, the decrease in emergency attendance may be a sign of increasing complications and deaths from CVD in the long run and need consistent evaluation. The whole society should prepare for the potential increase in the disease burden of CVD.

Our study has strengths. First, during the study period, the outbreak of COVID-19 in China was significantly slowed down and was largely under control. After the study period, the regulation lowered down and the social order is recovering. Thus, the results described a whole picture of the change in emergency attendance for stroke and AMI during a relatively complete lockdown period, providing valuable information, especially for regions where the outbreak is still going on. Besides, not the same as most existing reports, the reductions estimated in this study were accounted for the secular trend and other confounders, such as meteorological and air pollution factors, which makes the estimations more precise. Limitations also exist in the study. First, the estimation will be more precise with a longer observational period. However, the database used in this study was just set up in 2018, and no earlier emergency attendance can be obtained. Despite this, the large number of emergency attendances in the whole region helped to get reliable estimates. The results from the sensitivity analysis also support the main results. Besides, the study setting was in Beijing, where no more than 500 COVID-19 cases happened during the whole lockdown period with a relatively lower infection rate of COVID-19. Also, the most strict regulations were conducted during the lockdown period. Results interpreted to other regions should be cautious.

In conclusion, the emergency attendance for stroke and AMI cut in half at the beginning of the pandemic then had gradual restoration thereafter. The results hint the need for more engagement and communications with all stakeholders to reduce the negative impact on CVD emergency medical services during the crisis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Information 1 (DOCX 23 kb)

Author contributions

Conceptualization, YW, FC, YW, YL, and HS; Data curation, YW, ZS and YZ; Formal analysis, YW; Funding acquisition, YW and HS; Methodology, YW and WF; Project administration, YW, YL, and HS; Resources, ZS, YZ, YS, YL and HS; Supervision, YW, YL, and HS; Validation, FC; Visualization, YW; Writing—original draft, YW; Writing—review & editing, YW, FC, ZS, YZ, YS, WF, YW, YL, and HS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research, Grant Number: 2020-2-2014; Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Number: 81703291.

Data availability

The data supported this work can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that they have no conflict of interest..

Ethical approval

This work is approved by the Ethnic Committee of Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yiqun Wu and Fei Chen have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuping Wang, Email: wangyuping01@sina.cn.

Ying Liu, Email: 13901124008@139.com.

Haiqing Song, Email: songhq@xwhosp.org.

References

- 1.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of "alarming levels" of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2020;368:m1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leira EC, Russman AN, Biller J, Brown DL, Bushnell CD, Caso V, Chamorro A, Creutzfeldt CJ, Cruz-Flores S, Elkind MSV, Fayad P, Froehler MT, Goldstein LB, Gonzales NR, Kaskie B, Khatri P, Livesay S, Liebeskind DS, Majersik JJ, Moheet A, Romano JG, Sanossian N, Sansing LH, Silver B, Simpkins AN, Smith W, Tirschwell DL, Wang DZ, Yavagal DR, Worrall BB. Preserving stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic: potential issues and solutions. Neurology. 2020;95(3):124–133. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J, Li H, Kung D, Fisher M, Shen Y, Liu R. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on stroke care and potential solutions. Stroke. 2020;51(7):1996–2001. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.120.030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudilosso S, Laredo C, Vera V, Vargas M, Renú A, Llull L, Obach V, Amaro S, Urra X, Torres F, Jiménez-Fàbrega FX, Chamorro Á. Acute stroke care is at risk in the era of COVID-19: experience at a comprehensive stroke center in barcelona. Stroke. 2020;51(7):1991–1995. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.120.030329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pop R, Quenardelle V, Hasiu A, Mihoc D, Sellal F, Dugay MH, Lebedinsky PA, Schluck E, La Porta A, Courtois S, Gheoca R, Wolff V, Beaujeux R. Impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on acute stroke pathways—Insights from the Alsace region in France. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(9):1783–1787. doi: 10.1111/ene.14316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kansagra AP, Goyal MS, Hamilton S, Albers GW. Collateral effect of Covid-19 on stroke evaluation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):400–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2014816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sylaja PN, Srivastava MVP, Shah S, Bhatia R, Khurana D, Sharma A, Pandian JD, Kalia K, Sarmah D, Nair SS, Yavagal DR, Bhattacharya P. The SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and challenges in stroke care in India. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1473(1):3–10. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Filippo O, D'Ascenzo F, Angelini F, Bocchino PP, Conrotto F, Saglietto A, Secco GG, Campo G, Gallone G, Verardi R, Gaido L, Iannaccone M, Galvani M, Ugo F, Barbero U, Infantino V, Olivotti L, Mennuni M, Gili S, Infusino F, Vercellino M, Zucchetti O, Casella G, Giammaria M, Boccuzzi G, Tolomeo P, Doronzo B, Senatore G, Grosso Marra W, Rognoni A, Trabattoni D, Franchin L, Borin A, Bruno F, Galluzzo A, Gambino A, Nicolino A, Truffa Giachet A, Sardella G, Fedele F, Monticone S, Montefusco A, Omedè P, Pennone M, Patti G, Mancone M, De Ferrari GM. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1):88–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonardi M, Padovani A, McArthur JC. Neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19: a review and a call for action. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1573–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09896-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Violi F, Pastori D, Cangemi R, Pignatelli P, Loffredo L. Hypercoagulation and antithrombotic treatment in coronavirus 2019: a new challenge. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(6):949–956. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boukhris M, Hillani A, Moroni F, Annabi MS, Addad F, Ribeiro MH, Mansour S, Zhao X, Ybarra LF, Abbate A, Vilca LM, Azzalini L. Cardiovascular implications of the COVID-19 pandemic: a global perspective. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(7):1068–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds K, Go AS, Leong TK, Boudreau DM, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Fortmann SP, Goldberg RJ, Gurwitz JH, Magid DJ, Margolis KL, McNeal CJ, Newton KM, Novotny R, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Rosamond WD, Smith DH, VanWormer JJ, Vupputuri S, Waring SC, Williams MS, Sidney S. Trends in incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction in the cardiovascular research network (CVRN) Am J Med. 2017;130(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Wilkins E, Townsend N. Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart. 2016;102(24):1945–1952. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, Wu Y, Wang M, Wang Z, Wang S, Wang J, Wu J, Wu T, Chang C, Hu Y. Impact of a comprehensive tobacco control policy package on acute myocardial infarction and stroke hospital admissions in Beijing, China: interrupted time series study. Tob Control. 2020 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchis-Gomar F, Perez-Quilis C, Leischik R, Lucia A. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(13):256. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen K, Breitner S, Wolf K, Hampel R, Meisinger C, Heier M, von Scheidt W, Kuch B, Peters A, Schneider A. Temporal variations in the triggering of myocardial infarction by air temperature in Augsburg, Germany, 1987–2014. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(20):1600–1608. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claeys MJ, Rajagopalan S, Nawrot TS, Brook RD. Climate and environmental triggers of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(13):955–960. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng RD, Chang HH, Bell ML, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, Dominici F. Coarse particulate matter air pollution and hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases among Medicare patients. JAMA. 2008;299(18):2172–2179. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Yang J, Yang W, Wang C, Bärnighausen T. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):764–766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan A, Liu L, Wang C, Guo H, Hao X, Wang Q, Huang J, He N, Yu H, Lin X, Wei S, Wu T. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1915–1923. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing ZC, Zhu HD, Yan XW, Chai WZ, Zhang S. Recommendations from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital for the management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1791–1794. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He Y, Hong T, Wang M, Jiao L, Ge Y, Haacke EM, Li T, Hongqi Z. Prevention and control of COVID-19 in neurointerventional surgery: expert consensus from the Chinese Federation of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology (CFITN) and the International Society for Neurovascular Disease (ISNVD) J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(7):658–663. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Chen Y, Li Z, Wang D, Wang Y. Providing uninterrupted care during COVID-19 pandemic: experience from Beijing Tiantan Hospital. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(2):180–184. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rashidian A, Joudaki H, Khodayari-Moez E, Omranikhoo H, Geraili B, Arab M. The impact of rural health system reform on hospitalization rates in the Islamic Republic of Iran: an interrupted time series. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(12):942–949. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.111708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medeiros de Figueiredo A, Daponte Codina A, Moreira Marculino Figueiredo DC, Saez M, Cabrera León A. Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 incidence and mortality in China: an interrupted time series study. Bull World Health Organ. 2020 doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.256701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian Y, Liu H, Si Y, Cao Y, Song J, Li M, Wu Y, Wang X, Xiang X, Juan J, Chen L, Wei C, Gao P, Hu Y. Association between temperature variability and daily hospital admissions for cause-specific cardiovascular disease in urban China: a national time-series study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(1):e1002738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ab Manan N, Noor Aizuddin A, Hod R. Effect of air pollution and hospital admission: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(4):670–678. doi: 10.29024/aogh.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kontopantelis E, Doran T, Springate DA, Buchan I, Reeves D. Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h2750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Team RC . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markus HS, Brainin M. COVID-19 and stroke-A global World Stroke Organization perspective. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(4):361–364. doi: 10.1177/1747493020923472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes JL, Brake S, Docherty M, Lilford R, Watson S. Emergency ambulance services for heart attack and stroke during UK's COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):e93–e94. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31031-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AHA/ASA Stroke Council Leadership Temporary emergency guidance to US stroke centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51(6):1910–1912. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.120.030023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goyal M, Ospel JM, Southerland AM, Wira C, Amin-Hanjani S, Fraser JF, Panagos P. Prehospital triage of acute stroke patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2263–2267. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.120.030340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baracchini C, Pieroni A, Kneihsl M, Azevedo E, Diomedi M, Pascazio L, Wojczal J, Lucas C, Bartels E, Bornstein NM, Csiba L, Valdueza J, Tsvigoulis G, Malojcic B. Practice recommendations for the neurovascular ultrasound investigations of acute stroke patients in the setting of COVID-19 pandemic: an expert consensus from the European Society of Neurosonology and Cerebral Hemodynamics. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27(9):1776–1780. doi: 10.1111/ene.14334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer D, Meyer BC, Rapp KS, Modir R, Agrawal K, Hailey L, Mortin M, Lane R, Ranasinghe T, Sorace B, von Kleist TD, Perrinez E, Nabulsi M, Hemmen T. A stroke care model at an academic, comprehensive stroke center during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(8):104927. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information 1 (DOCX 23 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data supported this work can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.