Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a leading cause of hospital readmissions. There is great interest in approaches to efficiently predict emerging HF-readmissions in the community setting. We investigate the possibility of leveraging streaming telemonitored vital signs data alongside readily accessible patient profile information for predicting evolving 30-day HF-related readmission risk. We acquired data within a non-randomized controlled study that enrolled 150 HF patients over a 1–year post-discharge telemonitoring and telesupport programme. Using the sequential data and associated ground truth readmission outcomes, we developed a recurrent neural network model for dynamic risk prediction. The model detects emerging readmissions with sensitivity > 71%, specificity > 75%, AUROC ~80%. We characterize model performance in relation to telesupport based nurse assessments, and demonstrate strong sensitivity improvements. Our approach enables early stratification of high-risk patients and could enable adaptive targeting of care resources for managing patients with the most urgent needs at any given time.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a highly prevalent chronic condition affecting ~40m worldwide [1,2]. In many countries, HF is a leading cause for hospital admissions, with 30-day readmission rates in the 25% range [3]. As such, the condition poses huge resource burdens on healthcare systems, incurs heavy costs on payers, and impacts patient quality of life[2,3]. To cater to these pressures, policy and clinical bodies have attempted to implement both incentive oriented approaches and support oriented approaches [4,5]. Both of these have had some signs of success, but also some challenges that could be mitigated by leveraging data and analytics more effectively.

First, reimbursement policies have been revised to incentivize or penalize hospitals based on HF readmission rates [4]. As such, both health systems and payers have had increasing interest in data-driven models to predict readmission risk and improve management. This has spurred development of many HF readmission risk prediction models [6-9]. Typically, these models employ administrative claims data, aggregate features, unstructured data or specific clinically relevant components from electronic health record (EHR) systems. However, as most of these models use EHR, they predict the risk at discharge [10]. Some models attempt to dynamically predict evolution of the readmission risk across admission, inpatient (IP) stay, and discharge by employing logistic regression based on statistical features (e.g., in [7]) or deep learning based on time series sequences [6]. However, these models are limited as they lack visibility over the crucial evolution of the patient’s state following hospital discharge in the days immediately preceding a readmission.

Second, clinical societies and care delivery systems have instituted guidelines for patient support, education and treatment optimization in case management and post-discharge settings [11,12]. Some studies have demonstrated that these efforts reduce readmissions and improve outcomes. However, many of these support and optimization programmes are highly resource-intensive, requiring large investments from already stretched case management, integrated care, nursing, allied health and/or community care professionals for home-based follow-ups. As a result, it remains difficult to scale these efforts across large patient groups or entire healthcare systems. One way to address this challenge could be to identify the subset of patients with highest propensity (or risk) for unscheduled hospital utilization, and then proactively target (allocate with priority) the limited support and intervention resources to these strata of patients.

To address the above challenges, a few studies have analyzed invasive measurements, surveys, and telemonitoring (TM) measures to assess evolving patient states in the post-discharge community setting [13–16]. In particular, telemedicine programmes offer a non-invasive framework for remote daily monitoring of physiological signs (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, body weight) in the home setting. But these approaches have remained impractical for widespread adoption and exhibit high numbers of false negatives and positives [17,18]. One recent study used data from a disposable non-invasive multisensor patch placed on the chest within a machine learning framework to predict HF hospitalization, but clinical efficacy is yet to be established [19]. Overall, limited works have used easily obtained home-based vital signs in the context of a patient’s clinical evolution for risk stratification. Further, studies that position these approaches within care delivery and implementation workflows are also limited.

Here, we report 30-day HF readmission risk prediction using a longitudinal sequence of vital signs data alongside readily accessible patient profile information acquired across a sequence of hospital visits and home-based telehealth assessments. We acquire data within a non-randomized controlled post-discharge telehealth management programme that comprised regular telemonitoring by patients and telesupport by professional nurses. We develop a recurrent neural network model to distill complex relations hidden in sequential data, account for the full data trajectory, and dynamically predict evolving 30-day HF readmission risk at each observation day in both inpatient and home settings. Importantly, our approach learns from the evolution of patient state across hospital visits and home assessments, and dynamically updates predictions whenever new recordings are available. We evaluate the model’s ability to detect emerging post-discharge utilization events. Further, we provide detailed characterizations of model performance in relation to nurse assessments based on symptoms information obtained via person-centered telesupport. Finally, we suggest possibilities for timely patient stratification and decision support to augment efficiency and efficacy of current post-discharge care management workflows.

Study Design

The data was acquired within a non-randomized controlled study aimed at leveraging telehealth services (telemonitoring and telesupport) to reduce and manage heart failure readmissions.

Study Site and Setting:

The study was conducted at the Changi General Hospital (CGH), Singapore. CGH is a 1000- bed tertiary acute hospital serving a 1 million population in Singapore, and is equipped with a specialist cardiology department and a dedicated health management unit (HMU) staffed by professionally trained nurse telecarers.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

The study targeted heart failure patients older than 21 years with life expectancy of more than 1-year and ability to use the remote monitoring technology platform. Patients with comorbidities of end-stage renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or coronary artery disease with need for bypass grafting were excluded. Further details on inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in [12].

Enrollment and Consent:

Research coordinators within the CGH cardiology team recruited patients at point of discharge from a heart failure related hospitalization, and enrolled them into a post-discharge telehealth management program [12]. A total of 150 patients were enrolled between November 2014-March 2017. All patients provided informed consent for participation in the programme and use of anonymized versions of their data for research.

Study Procedures:

Study procedures included telemonitoring, telesupport, and clinical data collation, conducted as part of routine care delivery and post-discharge follow-up service provision for all patients [12]. Telemonitoring entailed daily self-measurement of 3 vital signs: (a) blood pressure (BP), (b) heart rate (HR), and (c) body weight. Measurement devices (the Philips Motiva Continua BlueTooth scale and A&D UA-767PBT-C blood pressure device) were issued to patients as part of the programme. The recorded vital signs were wirelessly transmitted to a back-end platform to be monitored by HMU nurses. Telesupport comprised HMU nurse-initiated phone calls that followed a structured script to focus on assessment of worsening HF symptoms. Nurses offering the telesupport had access to the patients’ full medical history and recommendations. Recordings of the telesupport calls, and subsequent nurse’ notes and follow-up actions were collated. Additionally, the study team collated sociodemographic data, inpatient and emergency department utilization data, inpatient vital signs recordings, diagnosis and comorbidity information, and other data providing information on the patient’s HF profile through the study period. Each patient was observed for at least 1 year. Compliance to the telemonitoring and telesupport programmes was also tracked.

Ethics Approvals and Related Procedures:

The use of the retrospective data collected in the above study for purposes of this research on readmission risk prediction was approved by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (Protocol 1556561515). To maintain confidentiality and adhere to terms of consent, an independent trusted third party within the hospital anonymized all retrospective data for analyses and model development.

Cohort Characteristics for Analyses and Modeling:

For the purposes of analysis and model development, we considered patients who (a) had more than 1 recorded inpatient episode during the study period, and (b) submitted at least 1 home-based vital signs records between inpatient visits. This subset is termed as the ‘analysis cohort’. The first criterion enables definition of the outcomes (ground truth labels) for risk prediction and the second criterion ensures the necessary features for modeling dynamic evolution of risk in the home setting. Among the study cohort of 150 patients, 129 fulfilled the first criterion. Of these 129 patients, 117 fulfilled the second criterion. Hence, the final analysis cohort comprised a total of 117 patients (72 male, 45 female) with an average age of 65.69 (SD: 12.65), across a range of ethnic groups (46% Chinese, 33% Malay, and 8% Indian, 2% Eurasian and 11% others).

Overview of Data and Prediction Task

Figure 1 illustrates the longitudinal data accrued over sequential inpatient and home stays and the associated readmission outcomes. We consider a given patient P on some observation day D (during the observation period) at some point in the patient care journey. Input on day D is a sequence of data features comprising fixed patient information, the history of vital signs, and the history of administrative and clinical data from inpatient episodes up to and including day D (Figure 1, green). Output on day D is a binary outcome indicating whether or not there was an actualized HF-related readmission within the next 30 days from D. Both inputs and outputs evolve as the patient progresses through the hospital-to-home continuum.

Figure 1:

Illustration of data and prediction task. (A) Transition across hospital-to-home setting. (B) Longitudinal data accumulated across a sequence of hospital inpatient visits and home stays. Combinations of fixed features (gray), episodic features (light red for inpatient episodes), and high-resolution features (red inpatient, blue home) accrue based on the care setting. For high-resolution features, days with no records are indicated in light blue. (C) The 30D HF readmission outcome or “label” as a function of days. The prediction task is to map data sequences from (B) in green to the label at last observed day in that sequence from (C). A few days are provided as illustrative examples.

The prediction task is to automatically map the input sequences (study data features) to the output ground truth “label” (associated readmission outcomes): The input-output pair for patient P on day D is defined as . The sequential modeling objective is to learn a model M such that L = M(F) based on input-output pairs recorded across patients and observation days.

Data Extraction and Preparation

For each patient in the analysis cohort, we extracted four types of data for modeling. First, fixed features: demographic information (age, race, gender) and number of HF admissions in the 1 year before start of the programme (Figure 1B). Second, episodic features for each inpatient visit: hospital utilization data (length of stay), primary diagnosis codes (categorized as HF vs. non-HF), comorbidity information (number of comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index), functional NYHA status and prescription records. Third, inpatient vital sign recordings (heart rate, blood pressure and weight) based on regular clinical monitoring during the inpatient stay. Fourth, home vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure and weight) based on daily self-monitoring by patients during their home stays between inpatient visits. The first three types of data were extracted from the EHR systems while the fourth was extracted from the HMU systems. As the hospital visits are fewer and farther apart, we note that majority of the longitudinal records are home-based vital signs.

We crosslinked the four types of data, and constructed a time series capturing the temporal evolution of the above features. Figure 1B provides an illustration. First, for the fixed features, we repeat the records for every day of the observation period (Figure 1B gray). Second, for the episodic features, we capture the daily evolution during the inpatient stay (e.g., length of stay on first day of the inpatient episode would be 1, and on third day of the inpatient episode would be 3). We preprocess the prescription records to one-hot encoded format indicating whether any 1 of 4 therapeutic classes (Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists, Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors) were prescribed [6]. We carry forward the episodic features as of discharge date for the subsequent home stay period (Figure 1B light red to light pink). Finally, for the inpatient and home vitals, we include the available records on any observation day if at least one vital sign was recorded on that day (Figure 1B red and blue). For observation days with no vital sign recordings, we consider this as a “No Record” day (Figure 1B light blue).

Separately from data extracted and prepared for modeling, the telesupport and clinical data collated were utilized for comparative evaluations (as described in the relevant Results sections).

Feature Representation

For each patient P in the analysis cohort, we represent the data recorded on a series of time-ordered IP days and home days as a feature matrix , where T is the number of observation days (before the last inpatient visit) and Q is the number of features. For patient P, on any given day D, the feature sequence is , a D×Q matrix of features with history up to and including day D. Patient P has T such multivariate time-series sequences, one for each observation day. We do not consider observation days within and beyond the last IP visit as we do not have records of outcomes after the last IP visit.

To deal with the variable length sequences, we perform zero-padding and include masking features which indicate when length padding was performed. For “No Record” days, we account for the time elapsed between available samples with an additional feature that at day D indicates the time gap between D and the preceding day when observations available. For cases when we have multiple readings for any vital sign feature on any observation day, we condense by considering only the median value of all available readings (per vital sign) on that day. For any observation days with at least one vital signs record, but missing values for any other vital signs features, we impute the missing values with median of available corresponding records (for that patient). For observation days with missing values for any of the episodic features, we impute the missing values by propagating the last valid observation forward.

Following the above feature representation steps, we normalize the vital signs to the scale of [0,1] and standardize other fixed and episodic features to Z-scores. All categorical features are one-hot encoded.

Clinical Outcomes (“Labels”)

We define the clinical outcome of interest on any given day as the occurrence (or non-occurrence) of an HF-related readmission within the next 30-day horizon. The outcome evolves with the patient’s clinical state over the observation period and hence informs the sequential modeling. Per machine learning parlance, we also refer to this as ground truth “label”. For patient P, on observation day D, the outcome is denoted as , a binary indicator variable. We extracted the outcomes based on the dates of hospital visits and the diagnosis information associated with each hospital visit (heart failure related or not). We considered a hospital admission as HF-related if the primary diagnosis code (as per the International Classification of Diseases) was one of 8 relevant ICD-10 codes: T.I110, T.I130, T.I500, T.I501, T.I509, T.I2511, T.I420, and T.I48.

At each observation day D for patient P, the label is:

1: if there is any HF-related IP readmission within the next 30 days of D

1: if D is within the first half of any HF-related IP stay

0: Otherwise:

Our labeling scheme was clinically validated by health service research experts and cardiologists for relevance to the envisioned study objectives.

We illustrate the labeling scheme with some examples:

D If D corresponds to a day when patient P is at home and the patient has an HF-related inpatient episode at D+16 days, the is 1 indicating a high risk of readmission.

If patient P has HF-related inpatient episode on days 20-25, , and are 1 but and are 0. The assumption here is that within an HF-related inpatient episode, the days closer to admission are high risk but days closer to discharge are low risk.

If D corresponds to a day when patient P is at home and the patient has a non-HF-related inpatient episode at D+25, the is 0 indicating low risk of HF-readmission.

Dynamic Readmission Risk Prediction with Recurrent Neural Networks

Sequence Data:

Following the above steps, for each patient, we obtain multiple data sequences of different lengths. Each sequence is associated with a binary 30-day readmission outcome (Figure 1). We note that the distribution of sequences across outcome classes is highly imbalanced: 89.83% of sequences are associated with no-readmission or “0” class (23416 sequences) and only 10.17% of sequences are associated with the readmission or “1” class (2650 sequences). There was no statistical difference between the age, gender, race and length of hospital stay characteristics between sequences associated with no-readmission vs. with readmission classes (Wilcoxon test, p=0.94).

Dynamics of Modeling Task:

The modeling task on day D is to use sequential observations until (and including) day D to predict HF-related readmission risk within the next 30 days [D to D + 30]. This is intrinsically a dynamic task wherein (a) there is a need to account for the history or evolution trajectory leading up to current day D and (b) there is a need to dynamically update the prediction at the next day D+1 with new feature recordings.

Model Design:

Recurrent neural networks are well-suited for such dynamic prediction tasks based on sequential time-series datasets. In particular, long short-term memory (LSTM) neural networks have been employed to learn complex temporal correlations from longitudinal clinical time-series data [20]. For our task, we implemented an established bidirectional LSTM modeling framework. The bidirectional nature of the model is to take into account both historic and evolving dependencies in a sequence.

Implementation Details:

The model comprises an LSTM with 2 layers, followed by a dropout layer with probability of 0.5. Next is a fully-connected layer, followed by another dropout layer with probability of 0.5. Finally, a non-linear activation function using Softmax is applied for classification. The objective function is defined using cross-entropy loss function and l2-norm regularization. To address the imbalance in outcome classes, the training samples were weighted inversely to the class ratios for the loss calculation. For model training, we used Adam optimization [21] with the learning rate of 0.001 to optimize the weights while the gradient is computed using backpropagation over time. In addition to L2-regularization, use of dropout layers helps to avoid overfitting [22].

Experiments:

We trained, validated, and tested models following a stratified 3-fold cross-validation scheme at patient level (60% train, 7% validation, and 33% test). Thus, in each fold on average, the train set consisted of 15328 (SD: 667) samples from 70 patients (60%), validation set consisted of 2050 (SD: 210) samples from 8 patients (7%), and the test set consisted of 8689 (SD: 634) samples from 39 patients (33%). The cross-validation scheme ensures the model and performance results are not specific to the training:testing split. The training and validation are done with a batch-size of 64 for 100 epochs. In each fold, we chose the final model based on the validation performance. We ensured that there is no overlap between the data (and subset of patients) used to train the model and the data (and patient subset) used to test the performance of the model. We ran experiments on NVIDIA-SMI 418.56, python 3.7.

Compliance to Home-Based Telemonitoring

In order to provide intuition for the data characteristics and inform better interpretation of performance, we first present statistics on compliance to the telemonitoring programme (Figure 2). We observe that the 117 patients in the analysis cohort had on average 188.32 (SD: 134.64) days of vital signs records at home with a range of 2 to 413 days. Most patients tend to have either very low or very high numbers of telemonitoring observation days (Figure 2A). Further, a vast majority of the patients have less than 10 missing values for most vital signs (first bin, Figure 2B).

Figure 2:

Compliance to telemonitoring (TM). Normalized histograms of (A) average number of days with at least 1 TM vital signs recording. (B) number of missing vital signs.

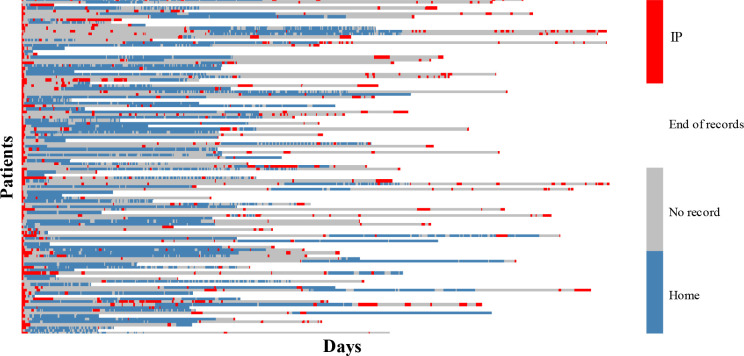

Figure 3 is a heatmap of the longitudinal vital signs data across patients and days. We align the start of recordings across patients as day 0. All patients start with an index inpatient episode before enrolment in the study. Each row shows all available records for one patient. For a given patient (row), red denotes days at which any subset of inpatient vitals are recorded, blue denotes days at which any subset of home vitals are recorded, gray denotes days within the observation period with no records, and white denotes the days after the end of observation period for that patient. We observe that different patients have different levels of compliance to the telemonitoring programme across days, different patterns of inpatient readmission, and different observation periods. This attests to the real-world diversity of our study cohort and data, and suggests that the results could be relevant to practical settings.

Figure 3:

Longitudinal evolution of vital signs records. Each row stands for one patient. Red cells show the IP visits and blue cells show TM days at home. The start of the records across patients is aligned by shifting and the length of longitudinal data across patients is different. The gray cells between red and blue show that no record is available while the white cells after the last blue/red in each row show the end of records for that patient.

Performance Evaluation

For sequences in the held-out testing sets, we quantitatively evaluated the model prediction against the ground truth outcome or “label”. Specifically, we characterized performance based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), the true positive rate or sensitivity, the true negative rate or specificity, and the F1-score. For each performance metric, we computed average and standard deviations across the test sets of the 3 folds.

Results: Dynamic Risk Prediction vs. Traditional Approaches

To evaluate the degree to which dynamic risk prediction based on sequential data impacts the model performance, we compared performance of the proposed LSTM approach to that of two traditional static modeling approaches (Logistic Regression or LR and Multi-layer Perceptron or MLP). For each of the methods, we employed the same data for the same prediction task at the same days. We also used the same inverse weighting (based on class ratios) for the loss calculation for all three methods, and report the best case results for LR and MLP− to ensure fair comparison.

As the LR and MLP models cannot learn with sequential data, we trained them to predict the risk on day D using all features at day D; and the summary statistics (mean and standard deviation) of the numerical features from days 1 to D-1. For the MLP, we used a 2 layer perceptron which contains 64 and 32 hidden units respectively on each layer with ReLU activations and chose the final model based on the validation performance.

Table 1 shows the 30D HF-related readmission risk prediction performance using the proposed LSTM model, LR model, and MLP model. Based on the results, LSTM outperforms the MLP and LR in terms of both sensitivity and specificity, and hence offers up to 3-4% gain in AUROC and F1-score. We note that LSTM offers a sensitivity increase of 7.53% and 1.35% over MLP and LR, respectively. Importantly, LSTM performance is more robust – as indicated by the smaller standard deviation (i.e., smaller variations) across folds. As the LSTM, LR and MLP models are all essentially minimizing the conditional log-likelihood for binary classification, we infer that the LSTM performance improvement may come primarily from the additional information contained in the sequential data trajectory. In other words, as the LSTM learns from entire data sequences, the increased performance suggests that the sequential trajectory of features provides additional predictive power.

Table 1.

30D readmission risk prediction results using LSTM, LR, and MLP. All numbers are in %, and reported as mean (standard deviation).

| AUROC % | Sensitivity % | F1-score % | Specificity % | |

| LSTM | 79.54 (4.50) | 71.05 (0.69) | 79.36 (4.80) | 75.18(6.05) |

| LR | 77.66 (3.25) | 69.70 (4.22) | 76.17 (8.06) | 70.71 (10.86) |

| MLP | 75.11 (2.62) | 63.52 (6.41) | 76.48 (4.11) | 71.95 (6.06) |

Results: Detection of Emerging 30D Readmissions

Next, we evaluate how dynamic readmission risk prediction based on telemonitoring data performs vis-à-vis person-centered telesupport approaches.

On the one hand, dynamic readmission risk prediction provides a data-driven means to detect emerging 30D HF readmissions. On the other hand, telesupport calls provide professional nurse telecarers a means to ascertain if a patient has concerning signs of HF decompensation and to advise patient to visit the hospital for urgent clinical intervention. For the latter, we regard a nurse’ advise to visit the hospital as an indicator of likely emerging readmission. For the telesupport calls considered, a certified HMU nurse who was blinded to the outcomes reviewed the source documents and verified the advise provided following each call.

We compared sensitivity and specificity of (a) dynamic readmission risk prediction based on telemonitoring data and (b) telesupport programme based detection of emerging readmission events. In each case, we evaluated performance on those observation days D’ when patients were at home, recorded telemonitoring vitals and received a telesupport call (i.e., days with risk assessment by both approaches). All metrics are calculated in relation to ground truth outcomes (“labels”). In order to provide visibility on performance in relation to when the next readmission occurs, we breakdown performance metrics based on ground truth outcomes in the 30D, 14D, and 7D horizon following the day of risk assessment D’.

Table 2 provides the results. We observe that the telesupport programme is highly specific (over 98%) with very limited false positives. On the other hand, the dynamic risk prediction based on telemonitoring provides greater sensitivity (up to 65%). These results hold independently of the horizon for the ground truth outcome.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity of risk prediction based on telemonitoring data and telesupport approaches for varying prediction-horizons.

| 30D | 14D | 7D | ||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Telemonitoring based Risk Prediction (LSTM) | 62.10 | 75.26 | 64.52 | 70.40 | 65.12 | 67.77 |

| Telesupport based Event Detection | 6.32 | 99.47 | 6.45 | 98.65 | 9.30 | 98.76 |

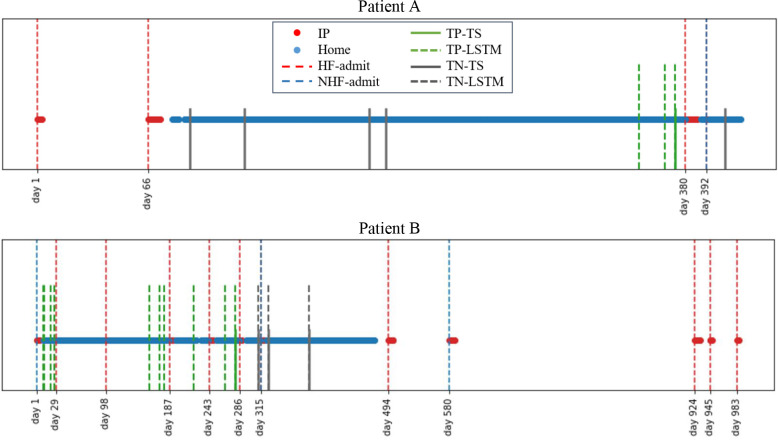

Figure 4 illustrates the performance of the 2 approaches against the ground truth outcomes trajectories for 2 patients. We note that the plots do not include all data-driven prediction days, rather only highlight days with both telemonitoring-based risk prediction and telesupport calls. For Patient A, the data-driven risk prediction approach flagged emerging risks earlier than the telesupport approach. However, the telesupport approach is highly specific in flagging true negatives. Patient B has several HF-related readmissions, but in many cases the telemonitoring data-driven risk prediction approach showed greater sensitivity for detecting the emerging readmission than the telesupport programme with concurrence only building up very close to one of the HF-readmissions. Further, as the telemonitoring data-driven approach predicts risks for 30 day HF-readmissions, it often detects emerging events earlier than it is feasible with the telesupport approach.

Figure 4.

Example cases. The red dots show IP records and blue dots show home-based records. The vertical red dash lines show HF admits while blue ones show non-HF (NHF) admits. The green and gray solid lines indicate true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) results by the telesupport (TS) programme. The green and gray dashed lines indicate TP and TN results with dynamic risk prediction (LSTM) based on telemonitoring data. Overlapping solid and dashed lines suggest concurrence between the two approaches.

These results suggest that the dynamic risk prediction model based on telemonitoring data could provide greater sensitivity and earlier identification of emerging HF-readmissions. This could allow the nursing and clinical teams the requisite time to reach out and stabilize the patient before deterioration to point of needing readmission. Yet, the dynamic risk prediction model may lead to false positives - hence the specificity of the telesupport calls in filtering out the false positives would be essential to assign appropriate follow-up actions. The complementary nature of the two approaches suggests that the best practice may involve using the dynamic risk prediction model to augment and direct the telesupport calls in a manner that is most time and resource-efficient for any given patient’s clnical needs.

Sensitivity to Type of Vital Signs and Frequency of Monitoring

Practical applicability of the above results could depend on patients complying to a regular home-based telemonitoring programme. Hence, we evaluated the sensitivity of the results to the type of vital signs and the frequency of monitoring. First, we re-trained models for cases when one of the three vital signs (BP, HR and weight) was entirely excluded from the feature sequences, and re-evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of dynamic risk prediction. Results (Table 3 column 2, 3, 4 vs. column 1) show that removal of BP, HR and weight reduce the sensitivity by 2.04%, 5.91% and 8.53% respectively. This suggests that weight and HR telemonitoring may be more important than BP for detection of emerging events. Second, we investigated the effectiveness of less frequent telemonitoring of vital signs. We retrained the models with only alternate days of telemonitoring during periods of continuous daily home monitoring, and re-evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of dynamic risk prediction. Results (Table 3 last column) show that reducing telemonitoring frequency to alternate days does not significantly impact the performance. In all cases, the AUROC remained above 78%. These results suggest that our approach is applicable in cases with reduction in types and frequency of vital signs monitoring. This offers conveniences that could encourage greater adoption.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity of 30D Readmission Risk Prediction with Varying Types and Frequency of Vital Signs Monitoring. All numbers are in % and the numbers in parentheses are SD values.

| All TM Days | Alternate TM Days | ||||

| All Features | No BP | No HR | No Weight | All Features | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 71.05 (0.69) | 69.01 (1.80) | 65.14 (4.21) | 62.52 (2.21) | 70.00 (2.27) |

| Specificity (%) | 75.18(6.05) | 73.34 (0.28) | 74.02 (4.79) | 72.21 (2.80) | 73.81 (6.36) |

Discussion

Our study investigated dynamic prediction of heart failure readmission risk based on longitudinal but non-invasive telemonitoring of vital signs and easily accessible heart failure profile information. Results demonstrate AUROC and F1 scores of 80%, and sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 75%, and suggest that remote monitoring in the community setting could enable automated, accurate, and sensitive prediction of 30-day HF-readmissions. Importantly, our method offers greater sensitivity for earlier detection of emerging readmission events than structured telesupport based post-discharge care programmes. As such, it offers the ability to augment current clinical or telehealth assessments of evolving heart failure status.

As such, our approach offers the exciting potential to proactively identify patients with high chance of HF-readmission in the community setting. This ability to flag high-risk patients up to 30 days before readmission could allow sufficient time for healthcare providers to assess and escalate the management plan, and to stabilize the patient at the primary care level before readmission becomes warranted.

Further, stratification of high-risk patients with more immediate needs could help to better target the telesupport efforts and enable more efficient use of limited community care resources. Current protocols assign community care professionals based on planned protocols that may not be targeted to the patients with the most intensive and immediate needs. In contrast, our home-based stratification approach would enable adaptive prioritization for timely yet efficient targeting of telesupport/community care to patients who need it when they need it.

Our vital signs telemonitoring approach is highly suitable for translation to home or community settings. First, unlike previous approaches that require administrative or clinical features only found in complex EHR systems, our approach relies on a carefully selected set of heart failure profile and vital signs features (demographics, history, functional state and prescriptions) that patients can readily access at home or community settings. Second, we showed the predictive value in a cohort with wide variations in compliance to vital signs telemonitoring, and demonstrated that performance is robust even with further reduction in the number of vital signs or frequency of monitoring.

Our results should be considered in the context of some limitations. The study was retrospective and non-randomized, and future expansions to blinded prospective studies could provide more evidence on impact measures and outcomes. While we employed cross-validation to reduce dependence of results on a fortuitous test set, the class imbalance does introduce dependence on the cross-validation setup. This could be addressed in future work that expands the study to larger multi-center cohorts.

This study provides insights into approaches to improve HF management and reduce readmissions by leveraging vital signs data from telemonitoring programmes. We now aim to work out the crucial clinical and telehealth workflow integration aspect to translate our findings to better decision support and patient self-management.

Acknowledgements:

Research efforts were supported by funding and infrastructure for Digital Health and Deep Learning from the Institute for Infocomm Research (I2R), Science and Engineering Research Council, A*STAR, Singapore (Grant Nos SSF A1718g0045, SSF A1818g0044, IAF H19/01/a0/023). The telehealth data acquisition was funded by the Economic Development Board (EDB), Singapore Living Lab Fund and Philips Electronics Hospital to Home Pilot Project (EDB grant S14-1035-RF-LLF H and W). The authors would like to acknowledge Royal Philips,

Singapore for their support in design and setup of the telemonitoring programme and for providing the platform for telemonitoring data extraction. The authors would also like to acknowledge valuable inputs from Oh Ying Zi and Teo Zhenwei at the CGH Department of Cardiology, insightful discussions with Nancy. F. Chen and Liu Zhengyuan at I2R, data extraction assistance from Ang C Yan (CGH Health Management Unit), recruitment assistance from CGH Case Management, and support for the study from the CGH Integrated Care Department.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Braunwald E. The war against heart failure: the Lancet lecture. Lancet. 2014;28(385(9970)):812–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Apr;63(12):1123–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allam A, Nagy M, Thoma G, Krauthammer M. Neural networks versus Logistic regression for 30 days all-cause readmission prediction. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45685-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The Prevention of Hospital Readmissions in Heart Failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashfaq A, Sant’Anna A, Lingman M, Nowaczyk S. Readmission prediction using deep learning on electronic health records. J Biomed Inform. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Jiang W, Siddiqui S, Barnes S, Barouch LA, Korley F, Martinez DA, et al. Readmission Risk Trajectories for Patients With Heart Failure Using a Dynamic Prediction Approach: Retrospective Study. JMIR Med informatics. 2019 Sep;7(4):e14756. doi: 10.2196/14756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao C, Ma T, Dieng AB, Blei DM, Wang F. Readmission prediction via deep contextual embedding of clinical concepts. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philbin EF, DiSalvo TG. Prediction of hospital readmission for heart failure: development of a simple risk score based on administrative data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 May;33(6):1560–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Chetrit E, Chen-Shuali C, Zimran E, Munter G, Nesher G. A simplified scoring tool for prediction of readmission in elderly patients hospitalized in internal medicine departments. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012. [PubMed]

- 11.Sulieman L, Fabbri D, Wang F, Hu J, Malin BA. Predicting Negative Events: Using Post-Discharge Data to Detect High-Risk Patients. AMIA. Annu Symp proceedings AMIA Symp. 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Leng Chow W, Aung CYK, Tong SC, Goh GS, Lee S, MacDonald MR, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring- enhanced support over structured telephone support in reducing heart failure-related healthcare utilization in a multi-ethnic Asian setting. J Telemed Telecare. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhang J, Goode KM, Cuddihy PE, Cleland JGF. Predicting hospitalization due to worsening heart failure using daily weight measurement: analysis of the Trans-European Network-Home-Care Management System (TEN-HMS) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009 Apr;11(4):420–7. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radhakrishna K, Bowles K, Zettek-Sumner A. Contributors to frequent telehealth alerts including false alerts for patients with heart failure: a mixed methods exploration. Appl Clin Inform. 2013 Oct 9;4(4):465–75. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2013-06-RA-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortara A, Pinna GD, Johnson P, Maestri R, Capomolla S, La Rovere MT, et al. Home telemonitoring in heart failure patients: the HHH study (Home or Hospital in Heart Failure) Eur J Heart Fail. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kohn MS, Haggard J, Kreindler J, Birkeland K, Kedan I, Zimmer R, et al. Implementation of a Home Monitoring System for Heart Failure Patients: A Feasibility Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(3):e46–e46. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apakama DU, Slovis BH. Using Data Science to Predict Readmissions in Heart Failure. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2019;7(4):175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bashi N, Karunanithi M, Fatehi F, Ding H, Walters D. Remote Monitoring of Patients With Heart Failure: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Jan;19(1):e18. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stehlik J, Schmalfuss C, Bozkurt B, Nativi-Nicolau J, Wegerich S, Rose K, et al. Continous Wearable Monitoring Analytics Predict Heart Failure Decompensation: THE LINK-HF Multi-Center Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Harutyunyan H, Khachatrian H, Kale DC, Ver Steeg G, Galstyan A. Multitask learning and benchmarking with clinical time series data. Sci Data. 2019;6(1):96. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingma DP, Ba J. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) CA, USA: San Diego; 2015. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J Mach Learn Res. 2014 Jun 1;15:1929–58. [Google Scholar]