Abstract

The amyloid-β protein precursor is highly expressed in a subset of inhibitory neuron in the hippocampus, and inhibitory neurons have been suggested to play an important role in early Alzheimer’s disease plaque load. Here we investigated bouton dynamics in axons of hippocampal interneurons in two independent amyloidosis models. Short-term (24 h) amyloid-β (Aβ)-oligomer application to organotypic hippocampal slices slightly increased inhibitory bouton dynamics, but bouton density and dynamics were unchanged in hippocampus slices of young-adult AppNL - F - G-mice, in which Aβ levels are chronically elevated. These results indicate that loss or defective adaptation of inhibitory synapses are not a major contribution to Aβ-induced hyperexcitability.

Keywords: Amyloidosis models, hyperexcitability, inhibitory synapses, presynaptic boutons, structural plasticity, two-photon imaging

INTRODUCTION

Proper functioning of neuronal networks in the brain requires balanced excitation and inhibition [1]. One of the earliest hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the deregulation of this balance, resulting in hyperactive neuronal networks [2–8]. This is associated with an increased prevalence of epilepsy, both in AD transgenic models [2, 4, 8, 9] and in humans [10–13]. In the healthy brain, the inhibitory system can quickly adapt to changes in network activity [14–16]. A local increase in excitation can trigger the formation of inhibitory synapses [17], whereas reduced network activity causes a loss of inhibitory synapses [18]. These adaptations serve to maintain a balance between excitation and inhibition and keep neuronal networks functional, despite ongoing changes in network level [16]. Defects in the inhibitory system are linked to several brain diseases, including AD [19–21], but possible defects in the dynamic adaptation of the inhibitory system have not been addressed.

Altered activity has been reported in both excitatory cells [6, 7, 22] and inhibitory cells [3, 5, 23], and is often linked to elevated levels of amyloid-β (Aβ) [2, 3, 22]. Aβ is the cleavage product of the presynaptic amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP), which is highly expressed in the hippocampus [24, 25]. In particular, AβPP is enriched in Reelin- and CCK-expressing inhibitory neurons on the border of the stratum radiatum and stratum lacunosum-moleculare [25, 26]. Depleting BACE-1 in inhibitory neurons alleviated Aβ-plaque load in early phase of AD [25], suggesting that the Aβ production from interneurons contribute to early disease stages. AβPP is present in presynaptic terminals, where it helps to regulate presynaptic function [27–29]. The presynaptic terminals of inhibitory synapses (boutons) are key dynamic elements of the adaptation capacity of the inhibitory system. Inhibitory boutons can rapidly appear and disappear along the axon in response to changes in activity or molecular signals [14, 30–32]. Aβ toxicity has been reported to specifically induce presynaptic impairments [33–36], including at inhibitory synapses [21], but it is unknown if Aβ interferes with synaptic dynamics in inhibitory axons.

In this study we examined inhibitory synaptic dy-namics in two amyloidosis models in parallel. We used two-photon microscopy to examine the dynamics of inhibitory boutons in GFP-labeled inhibitory axons in organotypic hippocampal slices after short (24 h) Aβ exposure and we compared these with hippocampal slices of APP-KI mice [37], in which Aβ levels were chronically elevated. To visualize inhibitory axons we make use of GAD65-GFP mice, in which a subset of inhibitory neurons, substantially overlapping with AβPP-expressing interneurons [25], are labeled with GFP [38].

METHODS

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines for the welfare of experimental animals issued by the Federal Government of The Netherlands. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical Review Committee (DEC) of Utrecht University.

GAD65-GFP mice express GFP in a subset of GABAergic interneurons, mainly in dendritic innervating interneurons [38, 39]. The AppNL - G - F (APP-KI) mouse model is a second generation amyloidosis model with three mutations in the humanized App-gene without overexpression of the App-gene [37]. APP-KI mice were crossed with GAD65-GFP mice to visualize inhibitory axons and boutons. The APP-KI mice were kept homozygous and the GAD65-GFP mice were kept heterozygous. GAD65-GFP mice from a separate breeding line were used as controls.

Brain slices

Hippocampal organotypic slices were prepared from P6-7 old GAD65-GFP mice as described be-fore [17, 31]. In short, pups were decapitated and their brain were cooled. The hippocampus was extracted and slices of 400μm thickness were prepared. Slices were kept in an incubator until use, between DIV10–20. Both genders were used. Organotypic slice cultures were treated with synthetic Aβ oligomers (Crossbeta Biosciences, Utrecht) for 24 h at a concentration of 0.4μg/mL, as described before [21]. At this concentration, these Aβ oligomers are able to block LTP in vivo [40]. The oligomers used here have been obtained using recombinant full length amyloid-β 1–42 peptide as starting material and based on a protocol that is described before [41]. The Aβ oligomers are chemically stabilized and uniform in size, without monomers or fibrils [40]. Corresponding concentrations of the vehicle served as control treatment.

Acute hippocampal slices were prepared from APP-KI and GAD65-GFP transgenic mice as des-cribed before [21]. In short, mice were sedated and decapitated at the age of 8 to 14 weeks and their brains were extracted. The brain was quickly removed and cooled. Subsequently, coronal slices of 300μm thickness were made. Data from both genders were pooled.

Two-photon imaging experiments

Acute and organotypic hippocampal slices were transferred to an imaging chamber, where they were continuously perfused with carbogenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; in mM: 126 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2 2H2O, 1.3 MgCl2 7H2O, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 Na2H2Po4, 20 glucose, pH ∼7.3, ∼315 mOsm) at a maintained temperature of 30–33°C. Live time-lapse two-photon microscopy images were acquired using a Femtonics 2D two-photon laser scanning microscope with a Nikon CFI Apochromat 60×NIR water-immersion objective. GFP was excited with 910 nm laser light (Mai Tai Hp, Spectra Physics). Image stacks (93.5μm × 93.5μm in xy, 1124 × 1124 pixels) with a 0.5μm step size in z were acquired (range: 29–42 z-planes). During the experiment, minor misalignments due to drift was manually corrected. Organotypic hippocampal slices were imaged over 150 min (15 time points). Acute slices were imaged for only 100 min (10 time point), due to stronger bleaching of the GFP signal, but image quality was otherwise comparable to organo-typic slices. Bleaching was similar in acute slices from APP-KI and GAD65-GFP mice.

Analysis

The analysis of inhibitory bouton dynamics was performed using a custom analysis software tool [17]. 1 to 5 axons per image were analyzed semi-automatically, with the researcher blinded to the condition. Bouton dynamics are determined by monitoring the same axon over all time points and determining bouton occurrence over time. We categorized boutons as described before ([31], see also Supplementary Figure 1). Boutons are divided in persistent boutons, which are present during the entire imaging period and non-persistent boutons, which are present only in a subset of time points. Non-persistent boutons are further classified into 5 sub-groups, based on their dynamics in the baseline (first 5 time points) and second imaging period (remaining time points). New boutons are only present in the second period, but not during baseline. Lost boutons are present during baseline and no longer in the second period. Stabilizing boutons are non-persistent during baseline and persistent in the second period. Destabilizing boutons are persistent during baseline and non-persistent in the second period. Intermittent boutons are non-persistent during the entire imaging period. Bouton density was calculated as the number of boutons divided by the axon length. The average fraction of persistent boutons was calculated as the number of persistent boutons dived by the average total number of boutons over all time point.

Statistical analysis was performed in Prism (Gra-phpad software). We used the unpaired two-tailed t-test (t; parametric) or a Mann-Whitney (MW; nonparametric) to compare two groups. Normality was tested with the D’Agostino & Pearson test. Multiple comparisons for bouton subgroups were performed with a 2-way ANOVA test (bouton subgroup × treatment). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Significance is reported as *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01.

RESULTS

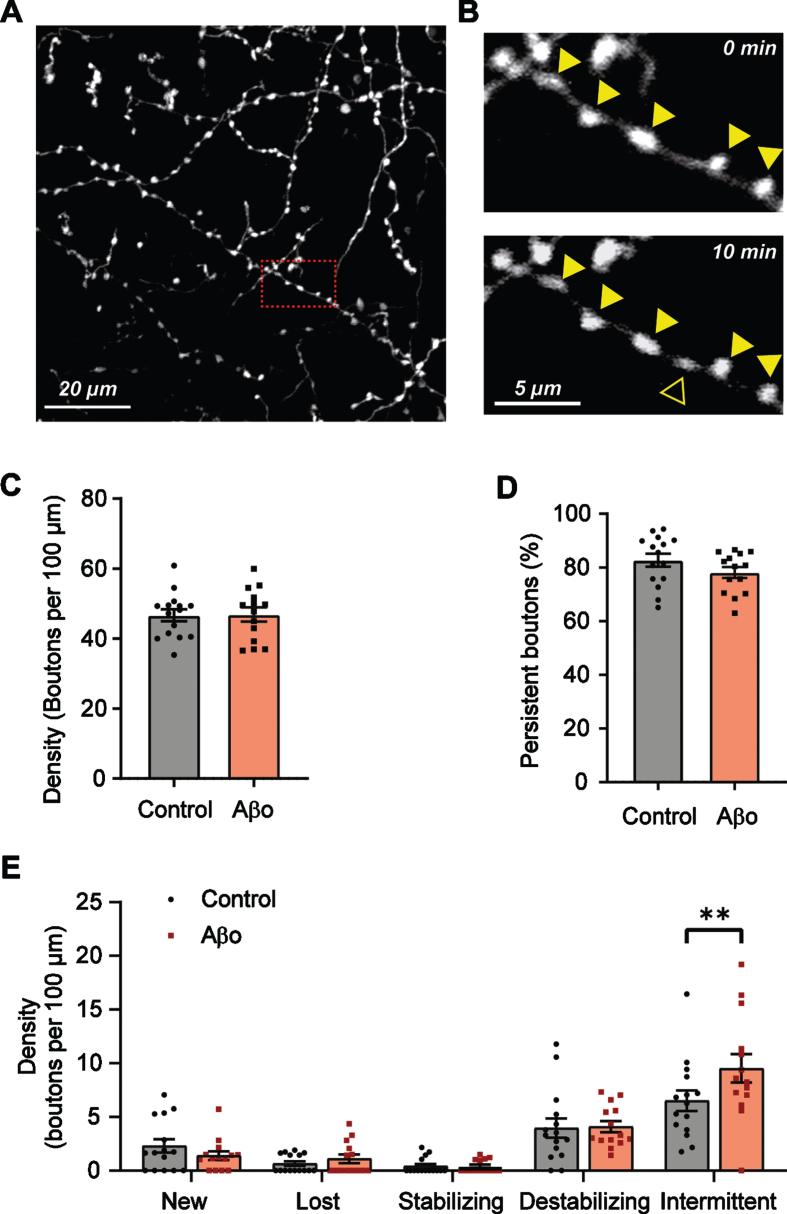

We performed two-photon time lapse imaging on GFP-labelled GABAergic axons in the CA1 area of organotypic slices of GAD65-GFP mice (Fig. 1A). In these mice, GFP-labelled interneurons are positive for CCK, reelin, and VIP, and do not express parvalbumin or somatostatin [38]. They partially overlap with AβPP expressing interneurons [25]. The slices were treated with control vehicle or 0.4μg/ml Aβ-oligomers for 24 h prior to live imaging. We monitored inhibitory axons and their boutons over time (10 time points with 10 min interval) and analyzed the appearance and disappearance of inhibitory boutons during the imaging period (Fig. 1B), as previously described [14, 30–32]. We distinguished two populations of boutons: persistent boutons which were present during the entire recording period, and non-persistent boutons which are present only in a subset of time points (see methods) [31]. 24 h Aβ treatment did not affect overall inhibitory bouton density (Fig. 1C). In control axons, 82.7%±2.3 of inhibitory boutons were persistent. After Aβ treatment, this was somewhat reduced to 78.1±2.0%(Fig. 1D), suggesting that inhibitory axons became slightly more dynamic after Aβ treatment. We further divided non-persistent bouton into five subgroups: new, lost, stabilizing, destabilizing, and intermittent boutons, based on their dynamics during the imaging period (see Methods and Supplementary Figure 1, [31]). The density of intermittent boutons was significantly increased in Aβ-oligomer treated slices (Fig. 1E), while the other subgroups remained unaffected. Together these results suggest that 24 h Aβ-oligomer treatment shifts inhibitory axons to a slightly more dynamic state.

Fig. 1.

Subtle increase in inhibitory bouton dynamics after 24 h Aβ oligomer treatment. A) Representative two-photon image of GFP-positive axons in the CA1 dendritic area of an hippocampal slice culture. B) Zoom-in (red box in A) of an inhibitory axon with boutons (closed triangles). A new bouton (open triangle) appears after 10 min. C) Average bouton density per 100μm of axon in Aβ-treated (Aβo) and control slices (t-test, p = 0.96). D) Percentage of persistent boutons (t-test, p = 0.16). E) Density of the different non-persistent bouton subgroups (see methods). Each data point represents one axon. Data from 3 independent experiments (2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc, left to right, p = 0.88, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.009), Bars plotted are mean±SEM; significance is indicated with **p≤0.01.

Bouton dynamics in a chronic model of amyloidosis

We wondered if a small increase in inhibitory bouton dynamics can lead to long-lasting changes in inhibitory synapses during chronic Aβ presence. We therefore repeated two-photon imaging of GFP-labelled inhibitory axons in slices from GAD65-GFP mice which were crossed with APP-KI mice, in which Aβ levels are chronically enhanced.

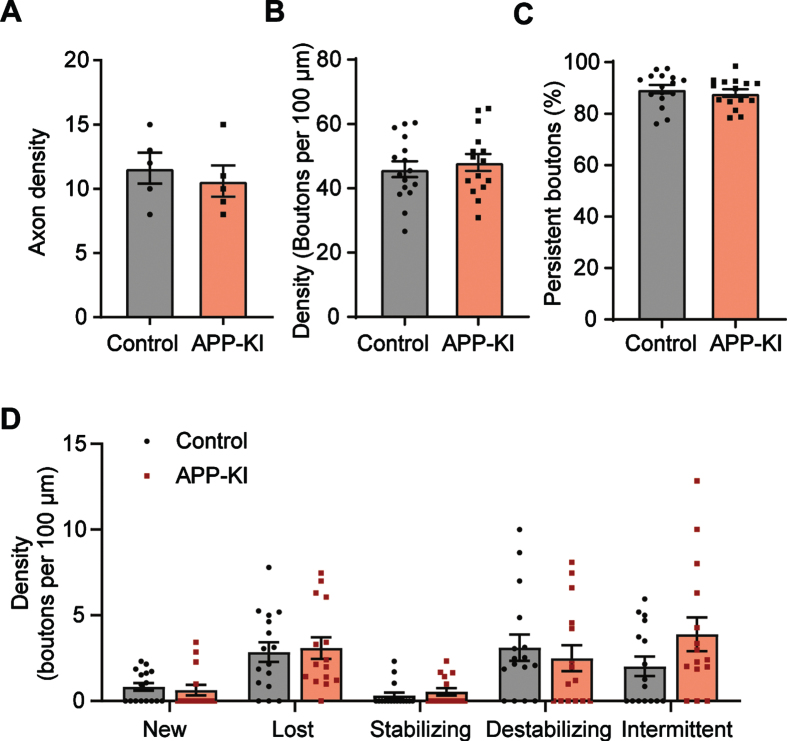

Acute slices were prepared from 8–14-week-old APP-KI and control mice, the age when the first plaques appear in APP-KI mice [25, 37]. First of all, there was no difference in the number of GFP-labelled axons in APP-KI and control slices (Fig. 2A), suggesting that chronic Aβ exposure did not lead to overall loss of GFP axons [3, 42]. This is consistent with a previous study in which axonal defects in somatostatin interneurons were only reported at a late stage, which appeared not directly related by Aβ toxicity [42]. The density of inhibitory boutons in GFP axons was similar in of APP-KI and control brain slices (Fig. 2B). Bouton densities were comparable in acute slices and organotypic slices, consistent with the notion that organotypic slices represent a mature network [43–45]. The fraction of persistent boutons was similar in APP-KI and control slices (Fig. 2C), suggesting that bouton dynamics were not affected by chronic Aβ exposure. Also when we analyzed the different bouton subgroups, no differences between APP-KI and control bouton dynamics were observed (Fig. 2D). Compared to organotypic cultures (Fig. 1E), acute slices showed a strong reduction in new and intermittent boutons, accompanied with an increase in lost boutons. This probably reflects a reduction in bouton formation and a loss of intermittent boutons in the acute slices. This resulted in a small reduction (7±2%) of overall bouton density at the end of the imaging period, but this was similar in control and AβPP slices. Together, this analysis indicates no difference in bouton number and dynamics in the APP-KI chronic amyloidosis model.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory boutons dynamics in brain slices from young APP-KI mice are normal. A) Density of GFP-positive axons in the total imaging volume (t-test p = 0.57). B) Average bouton density per 100μm of axon (t-test p = 0.56). C) Percentage of persistent boutons (t-test p = 0.49). D) Density of the different non-persistent bouton subgroups (see methods) (2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc, left to right, p = 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.95, 0.12). Each data point in B-D represents one axon. Data from 4 independent experiments. Bars plotted are mean±SEM.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used two-photon microscopy to examine the dynamics of inhibitory presynaptic boutons in two independent amyloidosis models of early AD. We found that Aβ exposure had only mild effects on inhibitory bouton dynamics. Aβ oligomer treatment in organotypic slices shifted inhibitory axons to a slightly more dynamic state, whereas chronic exposure to elevated Aβ levels in APP-KI mice did not affect inhibitory boutons dynamics.

It is previously reported that Aβ can induce impairments in release of neurotransmitter or peptides from presynaptic terminals [33–35], including at inhibitory synapses [21], but it is unknown if this will affect synaptic dynamics. Presynaptic defects may be specifically important in AβPP-expressing GABAergic neurons [25, 26], which axons are presumably exposed to the highest Aβ levels. We therefore imaged GFP-labeled inhibitory axons in GAD65-GFP slices, to maximize overlap with AβPP-expressing interneurons. We found that treating slices with 24 h of Aβ increased the number of intermittent boutons in GFP-labelled axons and displayed a trend towards a lower percentage of persistent bouton, suggesting a subtle destabilization of inhibition connections. A destabilization of inhibitory synapses can occur in response to a reduction in network activity [18, 46]. However, this explanation seems unlikely here as hypoactivity is only reported at later AD stages [2, 3, 23]. Acute Aβ exposure rather induces a mild hyperexcitability [2], and we have previously recorded an increased activity level in Aβ-treated slices [21].

As a second amyloidosis model, we utilized the APP-KI mice, which display an early build-up of Aβ [37, 47]. In hippocampal slices of these mice, we could not detect any changes in GFP-labeled axons or their boutons. It is possible that subtle differences in bouton dynamics in APP-KI slices have gone undetected, as inhibitory bouton dynamics were much reduced in acute slices compared to organotypic slices (compare Fig. 1E with 2D). We can also not exclude that a transient rearrangement of inhibitory synapses has occurred before the experimental age. Network rewiring in AD has been reported in fMRI studies [48, 49], but these were at later stage and not at the cellular level. However, cumulative effects were absent, as overall density of inhibitory axons and boutons was similar in APP-KI and control slices. It is currently not known if the Aβ mutation in APP-KI mice which accelerates oligomerization [50, 51] also affect other Aβ properties.

Together, our experiments suggest that elevated Aβ levels do not lead to rearrangement or loss of in-hibitory synapses. As we have only monitored a subset of inhibitory axons in these experiments, we cannot rule out specific impairments at other inhi-bitory synapses. However, we consider this unlikely as the current findings are in line with our previous observations that the density of inhibitory synapses is not affected by Aβ exposure, and that Aβ induces specific impairments in action potential driven GABA release [21]. Our study shows that short term application of Aβ induces only a subtle increase in inhibitory bouton dynamics, but we did not find any indications for a long-term effect on inhibitory bouton density after chronic exposure. Our study shows that Aβ-mediated impaired GABA release [21] is not accompanied by large changes in bouton stability or turnover. This could be interpreted as a failure of inhibitory axons to compensate for a reduction in neurotransmission. However, it could also indicate that bouton turnover is regulated independent of GABA release [46]. Either way, our results indicate that loss or defective adaptation of inhibitory synapses are not a major contribution to Aβ-induced hyperexcitability.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Alzheimer Nederland (WE.03-2016-04 and WE.03-2018-11). The authors thank Joris de Wit and Bart de Strooper for the AppNL - F - G/Gad65-GFP mouse line, Guus Scheefhals and Crossbeta Biosciences for the generous donation of the Aβ oligomers, and René van Dorland for excellent technical support.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ADR-200291.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O’Shea DJ, Sohal VS, Goshen I, Finkelstein J, Paz JT, Stehfest K, Fudim R, Ramakrishnan C, Huguenard JR, Hegemann P, Deisseroth K (2011) Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Busche MA, Chen X, Henning HA, Reichwald J, Staufenbiel M, Sakmann B, Konnerth A (2012) Critical role of soluble amyloid- for early hippocampal hyperactivity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 8740–8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu G-Q, Kreitzer A, Finkbeiner S, Noebels JL, Mucke L (2007) Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 55, 697–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Martinez-Losa M, Tracy TE, Ma K, Verret L, Clemente-Perez A, Khan AS, Cobos I, Ho K, Gan L, Mucke L, Alvarez-Dolado M, Palop JJ (2018) Nav1.1-Overexpressing interneuron transplants restore brain rhythms and cognition in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 98, 75–89.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Verret L, Mann EO, Hang GB, Barth AMI, Cobos I, Ho K, Devidze N, Masliah E, Kreitzer AC, Mody I, Mucke L, Palop JJ (2012) Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell 149, 708–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Sišková Z, Justus D, Kaneko H, Friedrichs D, Henneberg N, Beutel T, Pitsch J, Schoch S, Becker A, von der Kammer H, Remy S (2014) Dendritic structural degeneration is functionally linked to cellular hyperexcitability in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 84, 1023–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Hall AM, Throesch BT, Buckingham SC, Markwardt SJ, Peng Y, Wang Q, Hoffman DA, Roberson ED (2015) Tau-dependent Kv4.2 depletion and dendritic hyperexcitability in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 35, 6221–6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Minkeviciene R, Rheims S, Dobszay MB, Zilberter M, Hartikainen J, Fülöp L, Penke B, Zilberter Y, Harkany T, Pitkänen A, Tanila H (2009) Amyloid β-induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. J Neurosci 29, 3453–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L (2006) A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443, 768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Vossel KA, Ranasinghe KG, Beagle AJ, Mizuiri D, Honma SM, Dowling AF, Darwish SM, Van Berlo V, Barnes DE, Mantle M, Karydas AM, Coppola G, Roberson ED, Miller BL, Garcia PA, Kirsch HE, Mucke L, Nagarajan SS (2016) Incidence and impact of subclinical epileptiform activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 80, 858–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Irizarry MC, Jin S, He F, Emond JA, Raman R, Thomas RG, Sano M, Quinn JF, Tariot PN, Galasko DR, Ishihara LS, Weil JG, Aisen PS (2012) Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 69, 368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Vossel KA, Beagle AJ, Rabinovici GD, Shu H, Lee SE, Naasan G, Hegde M, Cornes SB, Henry ML, Nelson AB, Seeley WW, Geschwind MD, Gorno-Tempini ML, Shih T, Kirsch HE, Garcia PA, Miller BL, Mucke L (2013) Seizures and epileptiform activity in the early stages of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 70, 1158–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Scarmeas N, Honig LS, Choi H, Cantero J, Brandt J, Blacker D, Albert M, Amatniek JC, Marder K, Bell K, Hauser WA, Stern Y (2009) Seizures in Alzheimer disease: Who, when, and how common? Arch Neurol 66, 992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Frias CP, Wierenga CJ (2013) Activity-dependent adaptations in inhibitory axons. Front Cell Neurosci 7, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Herstel LJ, Wierenga CJ (2021) Network control through coordinated inhibition. Curr Opin Neurobiol 67, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Froemke RC (2015) Plasticity of cortical excitatory-inhibitory balance. Annu Rev Neurosci 38, 195–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Hu HY, Kruijssen DL, Frias CP, Rózsa B, Hoogenraad CC, Wierenga CJ (2019) Endocannabinoid signaling mediates local dendritic coordination between excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Cell Rep 27, 666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Keck T, Scheuss V, Jacobsen RI, Wierenga CJ, Eysel UT, Bonhoeffer T, Hübener M (2011) Loss of sensory input causes rapid structural changes of inhibitory neurons in adult mouse visual cortex. Neuron 71, 869–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Ambrad Giovannetti E, Fuhrmann M (2019) Unsupervised excitation: GABAergic dysfunctions in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 1707, 216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Palop JJ, Mucke L (2016) Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 777–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Ruiter M, Herstel LJ, Wierenga CJ (2020) Reduction of dendritic inhibition in CA1 pyramidal neurons in amyloidosis models of early Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 78, 951–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Zott B, Simon MM, Hong W, Unger F, Chen-Engerer H-J, Frosch MP, Sakmann B, Walsh DM, Konnerth A (2019) A vicious cycle of β amyloid-dependent neuronal hyperactivation. Science 365, 559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Hijazi S, Heistek TS, Scheltens P, Neumann U, Shimshek DR, Mansvelder HD, Smit AB, van Kesteren RE (2019) Early restoration of parvalbumin interneuron activity prevents memory loss and network hyperexcitability in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry 25, 3380–3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Del Turco D, Paul MH, Schlaudraff J, Hick M, Endres K, Müller UC, Deller T (2016) Region-specific differences in amyloid precursor protein expression in the mouse hippocampus. Front Mol Neurosci 9, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Rice HC, Marcassa G, Chrysidou I, Horré K, Young-Pearse TL, Müller UC, Saito T, Saido TC, Vassar R, De Wit J, De Strooper B (2020) Contribution of GABAergic interneurons to amyloid-β plaque pathology in an APP knock-in mouse model. Mol Neurodegener 15, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Wang B, Wang Z, Sun L, Yang XL, Li H, Cole AL, Rodriguez-rivera J, Lu H, Zheng H (2014) The amyloid precursor protein controls adult hippocampal neurogenesis through GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 34, 13314–13325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Laßek M, Weingarten J, Acker-Palmer A, Bajjalieh S, Muller U, Volknandt W (2014) Amyloid precursor protein knockout diminishes synaptic vesicle proteins at the presynaptic active zone in mouse brain. Curr Alzheimer Res 11, 971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Wang Z, Wang B, Yang L, Guo Q, Aithmitti N, Songyang Z, Zheng H (2009) Presynaptic and postsynaptic interaction of the amyloid precursor protein promotes peripheral and central synaptogenesis. J Neurosci 29, 10788–10801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Hick M, Herrmann U, Weyer SW, Mallm JP, Tschäpe JA, Borgers M, Mercken M, Roth FC, Draguhn A, Slomianka L, Wolfer DP, Korte M, Müller UC (2015) Acute function of secreted amyloid precursor protein fragment APPsα in synaptic plasticity. Acta Neuropathol 129, 21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Wierenga CJ, Becker N, Bonhoeffer T (2008) GABAergic synapses are formed without the involvement of dendritic protrusions. Nat Neurosci 11, 1044–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Frias CP, Liang J, Bresser T, Scheefhals L, van Kesteren M, Dorland van R, Hu HY, Bodzeta A, Van Bergen en Henegouwen PMP, Hoogenraad CC, Wierenga CJ (2019) Semaphorin4D induces inhibitory synapse formation by rapid stabilization of presynaptic boutons via MET co-activation. J Neurosci 39, 4221–4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Dobie FA, Craig AM (2011) Inhibitory synapse dynamics: Coordinated presynaptic and postsynaptic mobility and the major contribution of recycled vesicles to new synapse formation. J Neurosci 31, 10481–10493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Plá V, Barranco N, Pozas E, Aguado F (2017) Amyloid-β impairs vesicular secretion in neuronal and astrocyte peptidergic transmission. Front Mol Neurosci 10, 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. He Y, Wei M, Wu Y, Qin H, Li W, Ma X, Cheng J, Ren J, Shen Y, Chen Z, Sun B, Huang De F, Shen Y, Zhou YD (2019) Amyloid β oligomers suppress excitatory transmitter release via presynaptic depletion of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nat Commun 10, 1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Russell CL, Semerdjieva S, Empson RM, Austen BM, Beesley PW, Alifragis P (2012) Amyloid-β acts as a regulator of neurotransmitter release disrupting the interaction between synaptophysin and VAMP2. PLoS One 7, e43201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Hark TJ, Rao NR, Castillon C, Basta T, Smukowski S, Bao H, Upadhyay A, Bomba-Warczak E, Nomura T, O’toole ET, Morgan GP, Ali L, Saito T, Guillermier C, Saido TC, Steinhauser ML, Stowell MHB, Chapman ER, Contractor A, Savas JN (2021) Pulse-chase proteomics of the App knockin mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease reveals that synaptic dysfunction originates in presynaptic terminals. Cell Syst doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, Iwata N, Saido TC (2014) Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 17, 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Wierenga CJ, Müllner FE, Rinke I, Keck T, Stein V, Bonhoeffer T (2010) Molecular and electrophysiological characterization of GFP-expressing CA1 interneurons in GAD65-GFP mice. PLoS One 5, e15915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. López-Bendito G, Sturgess K, Erdélyi F, Szabó G, Molnár Z, Paulsen O (2004) Preferential origin and layer destination of GAD65-GFP cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex 14, 1122–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Tepper AW, de Boer EC, Hoogveld E, Vis JD, Schut IC, van Diggelen F, Vereyken IJ, Hoffmann M, Scheefhals GA (2015) Stable amyloid oligomers as tractable drug targets and versatile research tools in AD and PD. In AD/PD 2015: International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases, Nice. http://www.crossbeta.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/150305AT-Crossbeta-Poster-ADPD.pdf.

- [41]. Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Schmid LC, Mittag M, Poll S, Steffen J, Wagner J, Geis H-R, Schwarz I, Schmidt B, Schwarz MK, Remy S, Fuhrmann M (2016) Dysfunction of somatostatin-positive interneurons associated with memory deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Neuron 92, 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Bahr BA (1995) Long-term hippocampal slices: A model system for investigating synaptic mechanisms and pathologic processes. J Neurosci Res 42, 294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Mielke JG, Comas T, Woulfe J, Monette R, Chakravarthy B, Mealing GAR (2005) Cytoskeletal, synaptic, and nuclear protein changes associated with rat interface organotypic hippocampal slice culture development. Dev Brain Res 160, 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Muller D, Buchs PA, Stoppini L (1993) Time course of synaptic development in hippocampal organotypic cultures. Dev Brain Res 71, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Schuemann A, Klawiter A, Bonhoeffer T, Wierenga CJ (2013) Structural plasticity of GABAergic axons is regulated by network activity and GABAA receptor activation. Front Neural Circuits 7, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Sasaguri H, Nilsson P, Hashimoto S, Nagata K, Saito T, De Strooper B, Hardy J, Vassar R, Winblad B, Saido TC (2017) APP mouse models for Alzheimer’s disease preclinical studies. EMBO J 36, e201797397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Agosta F, Rocca MA, Pagani E, Absinta M, Magnani G, Marcone A, Falautano M, Comi G, Gorno-Tempini ML, Filippi M (2010) Sensorimotor network rewiring in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 31, 515–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Liu Z, Zhang Y, Yan H, Bai L, Dai R, Wei W, Zhong C, Xue T, Wang H, Feng Y, You Y, Zhang X, Tian J (2012) Altered topological patterns of brain networks in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state fMRI study. Psychiatry Res 202, 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Saido TC (2003) Dutch, Flemish, Italian, and Arctic mutations of APP and resistance of Aβ to physiologically relevant proteolytic degradation. Lancet 361, 1957–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Fan Z, McLean PJ, Hyman BT (2011) Characterization of oligomer formation of amyloid-β peptide using a split-luciferase complementation assay. J Biol Chem 286, 27081–27091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.