Abstract

The treatment of hyperphosphatemia remains challenging in patients receiving hemodialysis. This phase 1b study assessed safety and efficacy of EOS789, a novel pan-inhibitor of phosphate transport (NaPi-2b, PiT-1, PiT-2) on intestinal phosphate absorption in patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis therapy. Two cross-over, randomized order studies of identical design (ten patients each) compared daily EOS789 50 mg to placebo with meals and daily EOS789 100 mg vs EOS789 100 mg plus 1600 mg sevelamer with meals. Patients ate a controlled diet of 900 mg phosphate daily for two weeks and began EOS789 on day four. On day ten, a phosphate absorption testing protocol was performed during the intradialytic period. Intestinal fractional phosphate absorption was determined by kinetic modeling of serum data following oral and intravenous doses of 33Phosphate (33P). The results demonstrated no study drug related serious adverse events. Fractional phosphate absorption was 0.53 (95% confidence interval: 0.39,0.67) for placebo vs. 0.49 (0.35,0.63) for 50 mg EOS789; and 0.40 (0.29,0.50) for 100 mg EOS789 vs. 0.36 (0.26,0.47) for 100 mg EOS789 plus 1600 mg sevelamer (all not significantly different). The fractional phosphate absorption trended lower in six patients who completed both studies with EOS789 100 mg compared with placebo. Thus, in this phase 1b study, EOS789 was safe and well tolerated. Importantly, the use of 33 P as a sensitive and direct measure of intestinal phosphate absorption allows specific testing of drug efficacy. The effectiveness of EOS789 needs to be evaluated in future phase 2 and phase 3 studies.

Keywords: hemodialysis, intestine, phosphorus absorption, phosphorus radiotracer, sodium-phosphate cotransporters

Hyperphosphatemia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease.1–3 Furthermore, elevated phosphorus/phosphate (P) directly induces vascular calcification and secondary hyperparathyroidism4 and indirectly induces left ventricular hypertrophy mediated through fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).5–7 These adverse effects of hyperphosphatemia have led to the administration of P binders to reduce serum P levels in patients undergoing dialysis. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study indicated that 88% of patients undergoing dialysis are prescribed binders, and yet the average P level remains above target.8 Furthermore, in that same study, 45% of patients admitted to nonadherence to the binders.9 Therefore, alternative treatments to lower P are needed.

In patients with CKD, dietary P intake affects serum P level, and P bioavailability varies by food source.10–12 Although 24-hour urine studies have been considered surrogates of intestinal P absorption, we have shown from a secondary analysis of metabolic balance studies in CKD patients consuming a consistent controlled P diet that 24-hour urine P was unrelated to net intestinal P absorption from balance. Rather, 24-hour urine P was inversely related to whole-body P balance.13 Thus, even in moderate CKD patients who still produce urine, the use of 24-hour urine P as a biomarker of intestinal P absorption may not be accurate. In patients undergoing dialysis, where urine output is negligible, serum P has been used to study drug efficacy. However, the removal of P with dialysis, the rebound of serum P after dialysis, diurnal variability of serum P levels, and bone turnover with uptake and release of P vary among patients, and thus serum P is nonspecific in relation to intestinal absorption. To overcome these limitations, we adapted the direct and sensitive criterion-standard dual isotopic tracer that uses both 32P and 33P isotopes.14,15 We used oral and i.v. doses of 33P radiotracer to assess intestinal fractional P absorption after an oral dose, followed by compartmental changes and total body removal with the i.v. dose. This approach parallels our previous work in intestinal calcium absorption in patients with CKD.16

Intestinal P absorption includes both active (transcellular) and passive (paracellular) absorption. As recently reviewed, the major known and most studied intestinal P transporter is the sodium-P cotransporter NaPi-2b (SLC34).17 Studies in mice with CKD show that knocking out this transporter reduces hyperphosphatemia and bone loss.18,19 However, an NaPi-2b inhibitor, ASP3325, did not show efficacy in inhibiting P transport in human healthy subjects and in patients undergoing dialysis.20 Recent studies have also demonstrated the presence of both PiT-1 and PiT-2 (SLC20) in intestinal segments in humans,21 but their relative contribution to active P transport is unclear.22,23 Thus, it is possible that inhibition of PiT-1/2 may be required to significantly reduce active intestinal P transport in humans instead of inhibition of NaPi-2b alone.

EOS789 is a novel inhibitor of NaPi-2b, PiT-1, and PiT-2. EOS78924 inhibited sodium-dependent P uptake in in vitro cultured cells and inhibited sodium-dependent P uptake in brush border membrane vesicles prepared from rat small intestine. EOS789 inhibited intestinal P absorption in healthy rats in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, EOS789 given to hyperphosphatemic rats reduced serum concentrations of P, FGF23, and intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) in a dose-dependent manner.24 In phase 1 healthy human volunteer studies, there was a dose-dependent increase in P content of feces with doses administered safely up to 100 mg 3 times per day (t.i.d.) (N. Hisada et al., unpublished data, 2019). Side-effects included gastrointestinal symptoms as well as a reversible skin rash observed only at the highest dose. The observed efficacy in the healthy volunteer study provided the basis for testing in patients undergoing hemodialysis. The starting dose for this study of 50 mg t.i.d. was selected to provide a slightly lower dose than the maximal safe dose with pharmacodynamic activity data in the healthy volunteer study.

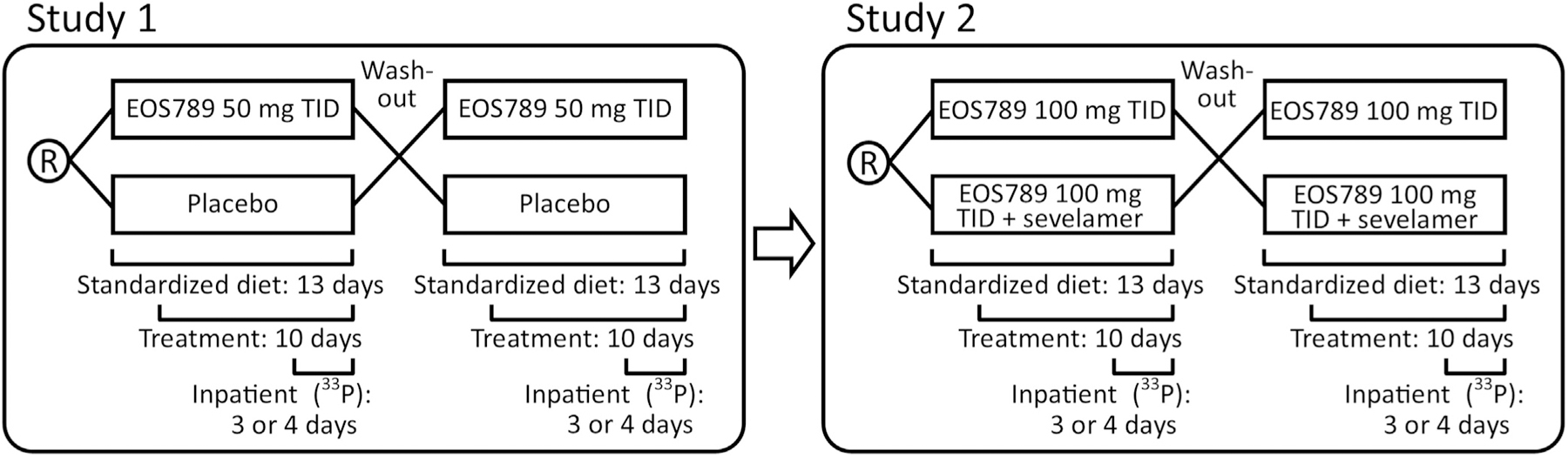

We report the use of this dual-33P radiotracer method in 2 phase 1b random-order crossover studies of identical design conducted in 10 patients per study with hyperphosphatemia receiving hemodialysis 3 times weekly (Figure 1). The first study (study 1) was a double-blinded study comparing 50 mg EOS789, a pan-phosphate transport inhibitor, and placebo t.i.d. with meals. The second study (study 2) was unblinded and compared 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. with and without 1600 mg sevelamer carbonate t.i.d. with meals. The primary end points were the safety of EOS789 and the drug’s efficacy in reducing intestinal P absorption as measured directly with the use of a radioisotope.

Figure 1 |. Schematic of study design.

Each study consisted of 2 sequences (arms) of 13–14 days duration with a 2-week wash-out between sequences. During the sequence, subjects had the study diet for the entire duration and the study drug began on day 4. The subjects were hospitalized in the Clinical Research Center on day 9 (first sequence for pharmacokinetics) or day 10 (second sequence) of each study. Patients underwent hemodialysis before admission and as the final event during the admission such that all of 33P studies were done between dialysis treatments.

RESULTS

Safety analyses

The number of patients who reported at least 1 adverse effect (AE), and the number of events for all four arms is presented in Table 1. Serious AEs occurred in 1 of 13 patients (7.7%; 2 events: lung abscess and osteomyelitis) treated with 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. and in 2 of 12 patients (16.7%; 3 events: cellulitis and heat stroke in 1 patient and bacteremia in 1 patient) treated with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug occurred in 1 of 13 patients (7.7%; 1 event: gastroenteritis) treated with 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. and in 1 of 12 patients (8.3%; 1 event: bacteremia) treated with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. The principle investigator (blinded to allocation) evaluated the available clinical information and determined a potential causal relationship with the study drug for all of the serious AEs. A detailed list of AEs by organ system is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1 |.

Adverse events (AEs)

| Arm | Patients with ≥1 AE, n (%) | Overall AEs, n | Patients with AEs considered related to EOS789, n (%) | AEs considered possibly related to EOS789, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 placebo (n = 13) | 7 (53.8) | 9 | 2 (15.4) | 2 (restless legs syndrome, abnormal liver function tests) |

| Study 1 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. (n = 13) | 6 (46.2) | 12 | 1 (7.7) | 1 (asthenia) |

| Study 2 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. (n = 12) | 6 (50.0) | 10 | 1 (8.3) | 3 (nausea, diarrhea, headache) |

| Study 2 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. + 1600 mg sevelamer carbonate t.i.d. (n = 11) | 7 (63.6) | 9 | 4 (36.4) | 4 (nausea, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, right bundle branch block) |

Efficacy analyses

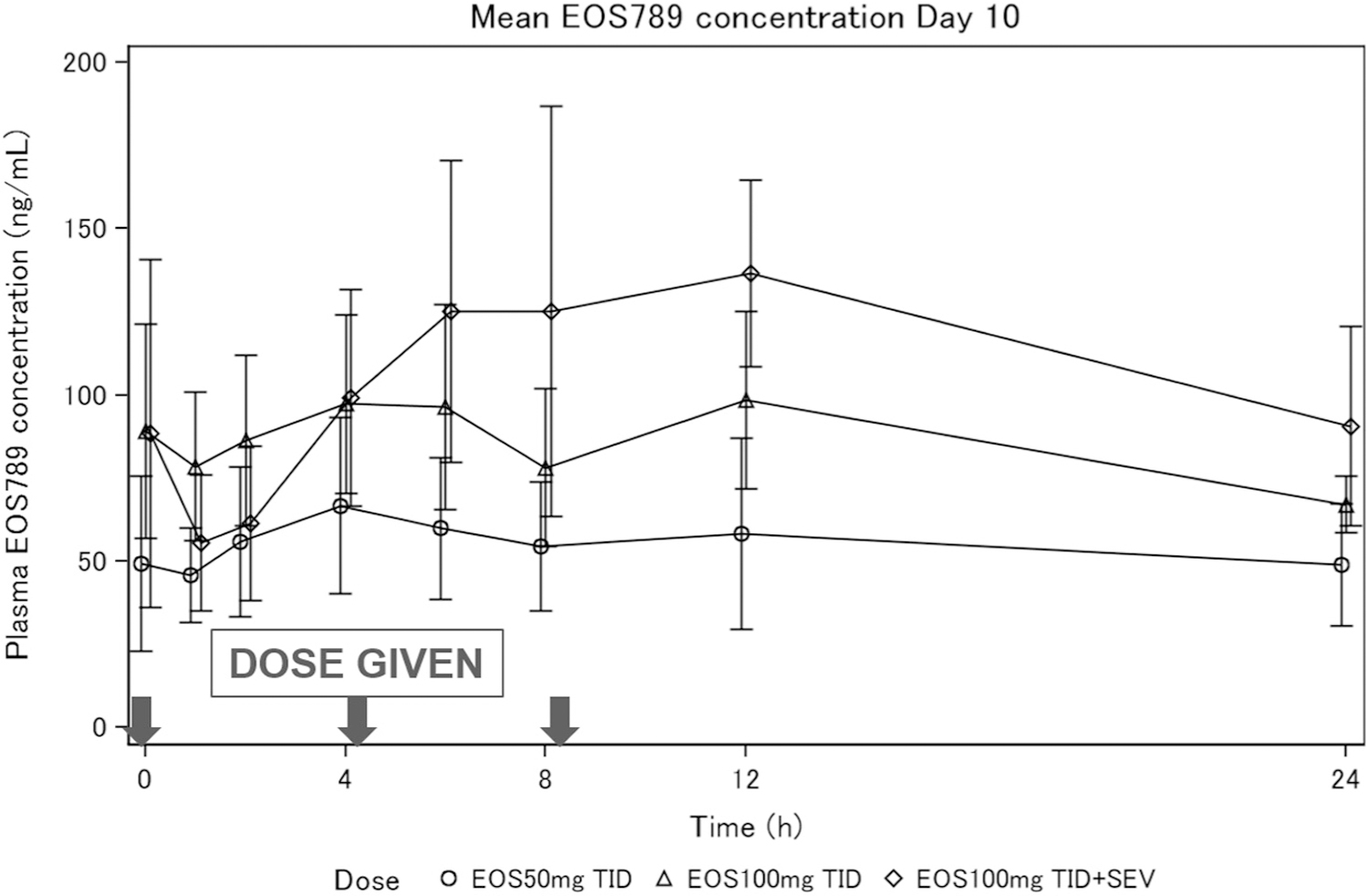

The demographics and baseline laboratory tests are presented in Table 2 and the patient allocation information in Supplementary Figure S1. Six patients completed both study 1 and study 2. The mean compliance rate of placebo/EOS789 treatments was a pill count of 95%–97%. The percentage of patients with treatment compliance by pill count ≥80% in each group was 91.7%–100.0%. The pharmacokinetic levels for EOS789 as a composite and by dose are shown in Figure 2 and individual patient curves in Supplemental Figure S2. The maximum concentration and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve were estimated with the plasma concentration profile, which was conducted for the period of 3 doses over 24 hours, corresponding to dosing at 0, 4, and 8 hours. The maximum concentrations for 50 mg t.i.d., 100 mg t.i.d., and 100 mg t.i.d. + sevelamer carbonate were 76.2 ± 24.2, 121 ± 20.3, and 188 ± 23.7 ng/ml, respectively; and means ± SDs of the areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve from time 0 to 24 hours were 1190 ± 387, 1900 ± 342, and 2560 ± 119 h‧ng/ml, respectively. The drug is highly protein bound (99.6% in humans), and therefore the removal rate with dialysis was negligible.

Table 2 |.

Subject Demographics and Baseline Biochemistries

| Baseline subject characteristics | Study 1 (n = 10) | Study 2 (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 52.3 ± 10.0 (median 52.0, range 41–69) | 56.7 ± 14.3 (median 55.0, range 38–85) |

| Age group, yr | ||

| 30–39 | 0 | 1 (10.0) |

| 40–49 | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| 50–59 | 4 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| 60–69 | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| >70 | 0 | 2 (20.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Female | 6 (60.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non–Hispanic or Latino | 10 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) |

| Race | ||

| Black or African American | 8 (80.0) | 9 (90.0) |

| White | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.4 ± 10.8 (median 28.0, range 20.7–53.3) | 32.0 ± 9.5 (median 30.2, range 20.6–52.5) |

| Tobacco use history | ||

| Never | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) |

| Current | 3 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) |

| Previous | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Dialysis vintage, yr | 5.24 ± 4.37 | 3.48 ± 2.27 |

| On VDRA | 9 (90.0) | 9 (90.0) |

| On calcimimetic | 3 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Serum P, mg/dl | ||

| Screening | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 1.1 |

| After binder washout | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 2.1 |

| After 3 days diet, baseline (before drug treatment)—first arm | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.8 |

| Baseline serum Ca, mg/dl | 8.9 ± 0.98 | 9.5 ± 0.9 |

| Baseline serum intact PTH, pg/ml | 529 ± 604 (median 398) | 354 ± 228 (median 339) |

| Baseline C-terminal FGF23 (RU/ml) | 37,085 ± 40,633 (median 15,781) | 30,888 ± 40,794 (median 14,941) |

| Baseline 1,25-vitamin D, pg/ml (reference ranges: male 18–64 pg/ml, female 18–78 pg/L) | 27.1 ± 13.9a range <8 to 51 | 35.7 ± 21a range <8 to 83 |

FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; PTH, parathyroid hormone; VDRA = vitamin D receptor analog.

For values <8, the number 8 was used to calculate the mean ± SD.

Values are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Figure 2 |. Pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses of EOS789.

Mean ± SD plasma EOS789 concentration at steady state (on day 10). PK sampling points were before morning dose and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours after. Doses were given at 0, 4, and 8 hours. Only the first sequence was used for the PK sampling, with n = 5–7 per group. Individual PK curves for each dose are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. SEV, sevelamer carbonate.

Mean [SEM] intestinal fractional P absorption in study 1 was 0.53 [0.06] (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–0.67) for placebo and was 0.49 [0.06] (95% CI 0.35–0.63) for 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. (difference of −0.04, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.10; P = 0.52) (Figure 3a), and in study 2 was 0.40 [0.05] (95% CI 0.29–0.50) for 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. and 0.36 [0.05] (95% CI 0.26–0.47) for 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. + sevelamer carbonate (difference of −0.03, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.06; P = 0.45) (Figure 3b). Cross-over period and randomized order effects were tested in the analysis of variance models and were not significant for either study 1 or study 2. The addition of potential confounders as covariates of peak plasma P, predialysis plasma P, or pre-post dialysis plasma P drop did not alter the nonsignificant results. In a preplanned secondary analysis of the 6 patients who completed both study 1 and study 2, intestinal fractional P absorption was lower with 100 mg EOS789 (0.44 [0.07]; 95% CI 0.29–0.59) compared with placebo (0.63 [0.07]; 95% CI 0.48–0.79) (difference of −0.19, 95% CI −0.365 to −0.03; nominal P = 0.028) and trended lower compared with 50 mg EOS789 (0.55 [0.07]; 95% CI 0.40–0.70) (difference of −0.11, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.05; P = 0.165) (Figure 4). There was not a significant relationship in the 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels and fractional P absorption when all treatments were considered (n = 19; r2 = 0.16; P = 0.09) (Supplementary Figure S3A). However, there was a strong correlation between the 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels and intestinal fractional P absorption in the patients from study 1 in the placebo arm (n = 9 owing to insufficient blood sample in 1 patient; r2 = 0.64; P = 0.009) (Supplementary Figure S3B).

Figure 3 |. Intestinal fractional P absorption by 33P.

Fractional P absorption in individual patients in (a) study 1 (comparing placebo vs. 50 mg EOS789 3 times per day [t.i.d.] with meals) and (b) study 2 (comparing 100 mg EOS789 vs. 100 mg EOS789 with sevelamer t.i.d. with meals). Each line represents 1 patient, EOS789–50 = 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d.; EOS789–100 = 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d.; EOS789–100 + Sev. = 100 mg EOS789 + 1600 mg sevelamer carbonate t.i.d.

Figure 4 |. Dose efficacy of EOS789 in intestinal fractional P absorption.

In a planned secondary analysis, data from the 6 patients who completed both studies were analyzed to generate a dose response comparing placebo, 50 mg EOS789 3 times per day (t.i.d.) and 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. There was a significant difference between placebo and EOS789–100 (P = 0.028).

The mean ± SD change from baseline to day 13 in serum P following treatment was −1.00 mg/dL [1.31] with placebo versus −1.28 ± 1.21 mg/dL with 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. in study 1 (difference of −0.3, 95% CI −1.03 to 0.38; P = 0.32), and −1.46 ± 1.34 mg/dL with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. versus −2.71 ± 1.73 mg/dL with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. + sevelamer carbonate in study 2 (difference of −1.47, 95% CI −2.07 to −0.87; P < 0.001). The majority of study participants did not have daily fecal excretion during the inpatient stay, limiting our evaluation of fecal data over the short 2-day collection period. However, available data show that accumulated fecal excretion of P (n = 8) trended lower in the subjects treated with 50 mg EOS789 t.i.d. compared with placebo by −279 mg/d (95% CI −883 to 324, means [SEs] 581 [200] and 860 [183] mg/d, respectively; P = 0.33). In study 2, accumulated fecal excretion of P (n = 6) trended lower in the subjects treated with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. + sevelamer carbonate compared with 100 mg EOS7789 t.i.d. alone by−226 mg/d (95% CI −549 to 97, means [SEs] 552 [92] and 777 [112] mg/d, respectively; P = 0.15). Urine collection was too sparse to evaluate or include in the absorption model. In study 1, there were no significant differences in serum P, corrected Ca, Ca × P, intact PTH, or C-terminal FGF23. In study 2, 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. + sevelamer carbonate lowered serum P, Ca × P, and serum intact PTH compared with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. alone (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2).

DISCUSSION

EOS789, an NaPi-2b, PiT-1, and PiT-2 inhibitor, was shown to be safe and well tolerated in patients undergoing hemodialysis. We elected to start at the lowest possible dose of 50 mg t.i.d. in this phase 1b study because the primary end point was safety and patients undergoing dialysis have many comorbidities. That dose was not effective compared with placebo in reducing intestinal P absorption. However, a preplanned secondary analysis of the 6 patients who were enrolled in both studies showed a nominally significant reduction in intestinal P absorption with 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. compared with placebo. Additional studies are required at higher doses of EOS789 and with more patients to determine efficacy.

Interestingly, intestinal P absorption in patients receiving 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. without versus with 1600 mg sevelamer t.i.d. was not different. However, serum P was lower at day 13 and fecal P was greater with the addition of sevelamer. Unfortunately, we did not have a treatment arm with sevelamer alone, making interpretation of this finding difficult. In humans, the relative proportion of passive absorption versus active transport is difficult to study. Larsson et al. found that an NaPi-2b inhibitor, ASP3325, was effective in lowering P in rodents but did not alter urine or fecal P excretion in healthy humans.20 In contrast, EOS789 in phase 1 studies in healthy individuals increased fecal P by 13.4–209 mg/d at the doses investigated (N. Hisada et al., unpublished data, 2019). This would suggest that pan-inhibition of NaPi-2b, PiT-1, and PiT-2 may be required. Paracellular absorption is also important in humans, as tenapanor, a gastrointestinal sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3) inhibitor that decreases paracellular P permeability and thus absorption,25 lowered serum P in dialysis patients.26 Interestingly, we did find a relationship between 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels and intestinal P absorption in the placebo arm, but not when all treatments were considered. However, given the interindividual variability in intestinal P absorption, and that most patients achieved normal levels with pharmacologic therapy of doxercalciferol, the role of vitamin D in intestinal transport as assessed in this methodology needs to be tested by prospectively assessing absorption before and after calcitriol administration.

In the present study, we demonstrated that the use of 33P radiotracer can be used in patients on hemodialysis to directly measure intestinal P absorption. Isotope techniques were used frequently in the 1960s and ‘70s,27 but have been sparsely used since owing to challenges including expense, subject burden, and radioactivity exposure. An accepted criterion-standard dual-isotope method for fractional P absorption requires use of both the low-energy beta-emitter 33P and the high-energy 32P, which is more hazardous. We adapted our previously published 45Ca radiotracer technique to 33P, where we mimicked a dual-isotope method using 33P for both the oral dose and the i.v. dose, staggering these by a day to differentiate between the oral and i.v. administrations in the specimens. After the measurement of 33P in serum following the oral administration, any residual 33P before the i.v. 33P administration is included in the model. All subsequent radioactivity counts in samples are considered to be from the i.v. 33P administration. This approach is possible because after 1 day, the detectable oral 33P dose remaining is an order of magnitude lower than the radioactivity counts assessed following the i.v. 33P dose (Figure 5). By containing the absorption test during the interdialytic period, we were able to account for i.v. clearance of the isotope for each subject individually to estimate intestinal fractional P absorption, despite differences in dialysis among patients and potential dialytic clearance.

Figure 5 |. Example of assessment of intestinal fractional P absorption with the use of a single isotope.

33P was used to assess fractional P absorption. Staggering the oral and i.v. 33P isotope administration by 1 day allows for the use of this single low-energy beta-emitter isotope. Kinetic modeling of the 33P radioactivity counts by liquid scintillation counting of plasma samples allows for calculation of intestinal fractional P absorption. dpm = disintegrations per minute.

A rigorous criterion-standard dual-isotope study would administer 2 isotopes on the same day and measure both isotopes from the same samples. Farrington et al.14 used oral 32P and i.v. 33P in patients with severe nondialysis CKD (creatinine clearance of 6 ± 4 ml/min), control subjects, and transplant recipients. They found that an initial rapid phase of intestinal absorption was completed by ~3 hours, but absorption continued at a slower rate through 7.5 hours, and that fractional absorption calculated from data through 24 hours was not different than calculations based on data only through 7.5 hours. As shown in our Figure 5, we allowed for 25 hours between the oral and i.v. doses of 33P, in which, based on the results reported by Farrington et al.,14 the absorption of the oral 33P isotope should have been completed. And although the oral 33P radioactivity counts were not back to baseline (similarly to observations by Farrington et al.), as described above, they were >10-fold less than the radioactivity counts following the i.v. 33P dose. Thus, this order of magnitude difference between oral and i.v. 33P radioactivity counts and the minimal additional absorption between 7.5 and 24 hours, as described by Farrington et al., allows for the use of this single-isotope modified absorption testing protocol. Furthermore, the criterion-standard dual-isotope method for P requires the use of 32P, which is more hazardous and less acceptable now for human use, so even a validation study of our single-isotope method against the dual-isotope method would be a challenge regarding acceptable risk to patients. Wiegmann and Kaye15 performed balance studies in hemodialysis patients with the use of a single isotope (32P) given 2 weeks apart, first by i.v., then by oral administration. In that study, 45Ca was also used, which precluded use of concurrent administration of 33P, which has similar energy peaks by scintillation counting. We surmise that the long duration between the i.v. and oral administrations was because the more hazardous 32P was used; thus, the longer duration spaced out the radioactivity exposures to the patients. However, this long duration between i.v. and oral isotope administrations is not ideal for assessing fractional absorption, because of lack of steady state over that time owing to a variety of predictable as well as unknown changing conditions, e.g., dialytic removal and fluctuating dietary intake.

A strength of our study was the controlled diet designed to provide consistent amounts of macronutrients and key micronutrients daily and evenly by meal. Our rotating 3-daycycle menu introduced some variation, which is a limitation in contrast to providing the exact same meals every day. However, use of cycle-menus are standard in controlled feeding and balance studies in humans to enhance participant recruitment and retention into these already burdensome studies. The menus were designed to be consistent in macronutrients and key micronutrient and even similar in proportion of animal and plant sources of protein, which can affect P bioavailability. In addition, the same menu was given during the P absorption study in the Indiana University Clinical Research Center (CRC) on both the oral 33P and i.v. 33P dose days. Additional limitations of our study were the sparse stool collections over the 2-day inpatient period, which precluded use of stool data in the kinetic model or measurement of stool P as a secondary measure of absorption, and that the 2-day absorption test period is not long enough for estimation of the slow turnover pools in the kinetic model (e.g., bone turnover), which would require a longer full metabolic balance study.

It is important to emphasize the multiple variables affecting serum P in patients on dialysis. Although many dialysis patients are anuric, some patients, especially those on peritoneal dialysis, retain residual renal function. Wang et al. demonstrated that anuric patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis had elevated serum P levels nearly twice as often as patients with residual renal function.28 The removal of P with dialysis varies considerably and is affected by blood flow, dialysis duration, predialysis serum P, PTH level, and ultrafiltration volume.29,30 Traditional thrice-weekly hemodialysis leads to a rebound of serum P from extracellular stores, including bone, after dialysis but the timing of that rebound varies.31–33 Recent studies demonstrated that hemodiafiltration, compared with hemodialysis, leads to greater removal of P owing to the expanded ultrafiltration34 and that nocturnal, compared with intermittent, dialysis removes more P.35 Increased bicarbonate dialysate may affect P removal,36 and flux of P out of bone may also vary depending on the bone turnover.29 Finally, even in dialysis patients there is diurnal variation in serum P levels, complicating predialysis measures across multiple dialysis shifts.20 Thus, studying P homeostasis in dialysis patients is very difficult, and direct assessment with the use of oral and i.v. 33P radiotracer as demonstrated in the present study is a way to confirm true drug efficacy at the intended target site of the intestine.

In summary, we present promising data for safety of a novel pan-inhibitor of sodium-phosphate cotransport in patients undergoing hemodialysis with the use of a novel technique of oral and i.v. 33P radiotracer kinetic modeling. Future studies are required to determine efficacy of higher doses of EOS789, the role of EOS789 with diets of differing P content, and the potential mechanisms by which intestinal P absorption varies in patients with CKD. In addition, long term safety studies are needed to assess any adverse effects of pan-phosphate transporter inhibition.

METHODS

Study design

Two phase 1b random-order crossover studies of identical design were conducted in patients with hyperphosphatemia receiving hemodialysis thrice weekly (NCT02965053; Indiana University Institutional Review Board approval 1608100544). The first study (study 1) was a double-blinded study comparing 50 mg EOS789 versus placebo t.i.d. with meals. The second study (study 2) was unblinded and compared 100 mg EOS789 t.i.d. with versus without 1600 mg sevelamer carbonate t.i.d. with meals. Twelve to 14 patients were recruited in each study to have a final number of 10 patients per study with all measurements from both treatments available for efficacy analyses. The first patient was consented in May 2017, and the last intervention for study 2 was in July 2018. See Supplementary Figure S1 for enrollment information. The primary end point for both study 1 and study 2 was safety and determined by adverse events and safety laboratory tests. Secondary efficacy end points for both studies were differences between the 2 treatments in (i) intestinal fractional P absorption, (ii) serum P, serum Ca, serum Ca × P, serum intact PTH, and serum C-terminal FGF23 at day 13, and (iii) accumulated fecal excretion of P from day 11 to 13. Plasma concentration and pharmacokinetics of EOS789 were determined in the first crossover session of each study before the 33P dosing (n = 6). The study schema is shown in Figure 1.

The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is detailed in Supplementary Table S3. In brief, patients were 18 years of age or older, on P binders, and on thrice-weekly hemodialysis for at least 3 months with no change in dialysis prescription or CKD–mineral and bone disorder drug treatments in the preceding 4 weeks. After informed consent, patients stopped their P binders for 15–19 days and underwent screening laboratory tests before dialysis. Those with serum P ≥7.0 mg/dL were eligible for the study and on day 1 began the controlled study diet of 900 mg/d P. The study diet was designed by a registered dietitian bionutritionist using ProNutra software (Viocare, Princeton, NJ). The diet consisted of a 3-day cycle menu, with assurance that patients had the same diet during the oral and i.v. 33P administration during each arm of each study while in the CRC. Meal composites were prepared, homogenized, and sent for analysis of minerals (Ca, P, Mg, Na, K) by means of inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry and protein content by means of the Dumas method (Covance Laboratories, Madison, WI). Nutrient content of each meal of the 3-day cycle menu is presented in Supplementary Table S4. All study meals were prepared in a metabolic kitchen, with ingredients weighed to 0.1 g accuracy and precision. For days 1–9, patients received their study diets as pack-out meals. Diet began on day 1, and on day 4 subjects underwent a prerandomization visit for baseline blood biochemistries. Those with serum P <10 mg/dL and increase in serum P by ≥0.5 mg/dL were randomized 1:1 by the Indiana University Investigational Pharmacy to receive the study drug (50 mg EOS789 or placebo in study 1, and 100 mg EOS789 with or without 1600 mg sevelamer carbonate in study 2). Patients continued the diet for a total of 13–14 days and the study drug for 10 days.

After 7 days of study drug, on day 10 of each treatment, patients were admitted to the CRC for pharmacokinetic testing. On day 11, blood was drawn and patients underwent their regular hemodialysis treatment. On returning to the CRC, they began the 33P absorption test protocol (see below). On day 13, patients had their final 33P blood drawn before dialysis and were discharged home. On day 28, subjects had a follow-up safety visit to either begin the second sequential treatment or complete the study. Thus, wash-out between the 2 arms was 28 days, chosen to account for more than 5 half-lives of the study drug. Pill counts were used to assess study drug compliance, and uneaten diet was estimated from returned checklists or review of the meal tray when in the CRC. Electrocardiography was performed in both studies, and echocardiography in study 2 for safety purposes. No changes in dialysis prescription (other than ultrafiltration) occurred during each study. Adverse events were monitored by a safety committee.

Biochemistries

Serum Ca, P, and other safety biochemistries were analyzed in the Indiana University Pathology Laboratories. Intact PTH was measured by means of Alpco Intact PTH ELISA (1–84), and C-terminal FGF23 was measured by Quidel Corp. human FGF-23 (Cterminal) ELISA Kit. 1,25(OH)2-Vitamin D levels were measured at baseline of each period by extraction/liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Intestinal fractional P absorption

Intestinal fractional P absorption was determined from oral and i.v. administration of 33P radiotracer. The method used mimicked the double-isotope method with the use of a single isotope by administering the oral isotope on the first day and the i.v. isotope on the second day. On day 11 after dialysis, baseline blood was drawn, then 10 μCi 33P (33P-orthophosphate; Perkin Elmer) was administered orally with lunch (which contained ~300 mg P) followed by 6 hours of blood draw (time points 15 and 30 min and 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, and 6 h after administration of 33P). Patients were asked to void urine and defecate before the oral administration of 33P. The 24-hour post–oral 33P blood sample was obtained on day 12 before the i.v. 33P administration. On day 12, 10 μCi 33P was then given i.v. (1 hour after lunch, or 25 hours after oral 33P), after a baseline blood draw (time point 0, before i.v. 33P), followed by 6 hours of blood draws at time points 15 and 30 minutes and 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, and 6 hours after administration of i.v. 33P). On day 13, the final, 24-hour post–i.v. dose blood sample for 33P was collected. During the 48-hour inpatient study, all feces and urine (if patient was not anuric) were collected. Fecal samples were homogenized, ashed in a muffle furnace (Thermolyne Sybron Type 30400; Dubuque, IA), and diluted with 2% nitric acid for mineral analysis (Optima 4300DV; Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT).16 Urine samples were acidified with 1% (vol./vol.) concentrated hydrogen chloride at the time of aliquotting, and diluted with 2% nitric acid for mineral analysis by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. 33P activity was measured in serum, urine, and feces by liquid scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 2910 TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). 33P tracer data in serum (% of dose/ml) and total P in serum (mg/dl) were used for kinetic modeling to determine fractional P absorption. Urine and fecal 33P and total P data were obtained in some patients over the 48 hours but were too sparse to be included in the modeling results. The 33P data were analyzed by means of compartmental modeling with the use of general equation–solving software (WinSAAM) with the percentage absorption calculated as the fraction of P moving into blood versus moving down the intestinal tract (Supplementary Figure S4). The model structure was determined from previous studies in healthy humans37; an example of the serum 33P curves following oral and intravenous 33P administration is shown in Figure 5.

Statistical analyses

This was a pilot study with a goal of having 10 patients complete both arms in each study to assess safety and efficacy of phosphorus absorption, with 12–14 patients recruited to ensure 10 completions. This sample size provided 80% power to detect AEs of true proportion of 16.7%. The safety population was defined as the 14 (study 1) and 12 (study 2) patients who received any study treatment and had at least 1 safety assessment visit. Safety was determined by the summary of AEs, vital signs, clinical laboratory tests, electrocardiograms, and echocardiograms. AEs were summarized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system. Drug relatedness was assessed by the principal investigator (who was blinded to treatment allocation) after reviewing all of the data available from each event. Efficacy analyses were conducted only on the patients that had complete data sets (n = 10 for each study). Demographic and baseline characteristics and exposure to study treatment were summarized by treatment for each study. The efficacy outcomes of interest were analyzed by means of an analysis of variance mixed model for crossover designs with the use of SAS software (v9.4; Cary, NC) with fixed effects for order, period, and treatment and random effects for subject nested within order. In exploratory analyses, peak plasma P, predialysis P, and pre-post dialysis drop in plasma P were examined as covariates in the analysis of variance models of treatment differences in intestinal fractional P absorption. In a secondary analysis, data from subjects who completed both study 1 and study 2 (n = 6) were analyzed for differences in intestinal fractional P absorption among placebo, 50 mg EOS789, and 100 mg EOS789 by means of an analysis of variance mixed model with fixed effects for treatment and random effects for subject. Two-sided statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

The pharmacokinetic analyses calculated individual and mean plasma EOS789 concentration versus time data were tabulated and plotted by dose level. The plasma pharmacokinetics of EOS789 was summarized by estimating total exposure (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) and maximum concentration. Calculation of EOS789 removal ratio during a single hemodialysis session was performed. All plasma samples for the pharmacokinetics analyses were collected only for the first treatment arm in each study.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. CONSORT diagram of recruitment.

Figure S2. Individual pharmacokinetic dose curves.

Figure S3. Relationship of vitamin D to phosphorus absorption. (A) 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels versus percentage phosphorus absorption in first period of each study. (B) 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels versus percentage phosphorus absorption of placebo arm in study 1 only.

Figure S4. Kinetic model.

Table S1. Numbers of patients with adverse events by event and period (safety population).

Table S2. Biochemical measures: serum P, Ca, Ca × P, intact PTH, and FGF23 at day 13.

Table S3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table S4. Study diets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was presented at the 2019 American Society of Nephrology meeting. This study was funded by Chugai. We thank the patients, dietitians, and nurses of the clinical research center, Indiana University Radiation Safety, Indiana University Health Investigational Pharmacy, and Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute, for their support. We also thank Dr. Athos Gianella-Borradori (Chugai at the time of the study) for comments.

DISCLOSURE

SMM receives consulting fees from Amgen and Ardelyx and grant support from Chugai (for this study) and Keryx/Akebia. All grants were paid directly to Indiana University. NH, TK, YO, NF, YM, and JS are employees of Chugai. This publication was made possible with partial salary support of KMHG (principal investigator) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K01DK102864 and partial salary support of ERS and the CRC from NIH grant UL1TR002529 (principal investigator, A. Shekhar).

Footnotes

DATA STATEMENT

The research data are held by Chugai Pharmaceuticals. The data sharing policy is available on the company website (www.chugai-pharm.co.jp/english/profile/rd/ctds_request.html).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kestenbaum B Mineral metabolism disorders in chronic kidney disease. JAMA. 2011;305:1138–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, et al. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15: 2208–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer SC, Hayen A, Macaskill P, et al. Serum levels of phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and calcium and risks of death and cardiovascular disease in individuals with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen NX, Moe SM. Pathophysiology of vascular calcification. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodelo-Haad C, Rodriguez-Ortiz ME, Martin-Malo A, et al. Phosphate control in reducing FGF23 levels in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kates DM, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL. Evidence that serum phosphate is independently associated with serum PTH in patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Floege J, Kim J, Ireland E, et al. Serum iPTH, calcium and phosphate, and the risk of mortality in a European haemodialysis population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1948–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopes AA, Tong L, Thumma J, et al. Phosphate binder use and mortality among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): evaluation of possible confounding by nutritional status. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fissell RB, Karaboyas A, Bieber BA, et al. Phosphate binder pill burden, patient-reported non-adherence, and mineral bone disorder markers: findings from the DOPPS. Hemodial Int. 2016;20:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA, et al. Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karp H, Ekholm P, Kemi V, et al. Differences among total and in vitro digestible phosphorus content of plant foods and beverages. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karp H, Ekholm P, Kemi V, et al. Differences among total and in vitro digestible phosphorus content of meat and milk products. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stremke ER, McCabe LD, McCabe GP, et al. Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus as a biomarker of dietary phosphorus intake and absorption in CKD: a secondary analysis from a controlled diet balance study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1002–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrington K, Mohammed MN, Newman SP, et al. Comparison of radioisotope methods for the measurement of phosphate absorption in normal subjects and in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Sci (Lond). 1981;60:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiegmann TB, Kaye M. Malabsorption of calcium and phosphate in chronic renal failure: 32P and 45Ca studies in dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 1990;34:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill KM, Martin BR, Wastney ME, et al. Oral calcium carbonate affects calcium but not phosphorus balance in stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;83:959–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks J The role of SLC34A2 in intestinal phosphate absorption and phosphate homeostasis. Pflugers Arch. 2019;471:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiavi SC, Tang W, Bracken C, et al. Npt2b deletion attenuates hyperphosphatemia associated with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23: 1691–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabbagh Y, O’Brien SP, Song W, et al. Intestinal Npt2b plays a major role in phosphate absorption and homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20: 2348–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson TE, Kameoka C, Nakajo I, et al. NPT-IIb inhibition does not improve hyperphosphatemia in CKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichida Y, Hosokawa N, Takemoto R, et al. Significant species differences in intestinal phosphate absorption between dogs, rats, and monkeys. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2020;66:60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Candeal E, Caldas YA, Guillen N, et al. Intestinal phosphate absorption is mediated by multiple transport systems in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G355–G366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candeal E, Caldas YA, Guillen N, et al. Na+-independent phosphate transport in Caco2BBE cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C1113–C1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuboi Y, Ohtomo S, Ichida Y, et al. EOS789, a novel pan-phosphate transporter inhibitor of multi-phosphate transporters, is effective for the treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder. Kidney Int. 2020;98:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King AJ, Siegel M, He Y, et al. Inhibition of sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 in the gastrointestinal tract by tenapanor reduces paracellular phosphate permeability. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Block GA, Rosenbaum DP, Yan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenapanor in patients with hyperphosphatemia receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a randomized phase 3 trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30: 641–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leggett RW. Proposed biokinetic model for phosphorus. J Radiol Prot. 2014;34:417–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang AY, Woo J, Sea MM, et al. Hyperphosphatemia in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients with and without residual kidney function: what are the implications? Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:712–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias RM, Alvares VRC, Moyses RMA. Phosphate removal during conventional hemodialysis: a decades-old misconception. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rafik H, Aatif T, El Kabbaj D. The impact of blood flow rate on dialysis dose and phosphate removal in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugisaki H, Onohara M, Kunitomo T. Dynamic behavior of plasma phosphate in chronic dialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1982;28:302–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minutolo R, Bellizzi V, Cioffi M, et al. Postdialytic rebound of serum phosphorus: pathogenetic and clinical insights. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viaene L, Meijers B, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. daytime rhythm and treatment-related fluctuations of serum phosphorus concentration in dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Svara F, Lopot F, Valkovsky I, et al. Phosphorus removal in low-flux hemodialysis, high-flux hemodialysis, and hemodiafiltration. ASAIO J. 2016;62:176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zupancic T, Ponikvar R, Gubensek J, et al. Phosphate removal during long nocturnal hemodialysis/hemodiafiltration: a study with total dialysate collection. Ther Apher Dial. 2016;20:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertocchio JP, Mohajer M, Gaha K, et al. Modifications to bicarbonate conductivity: a way to increase phosphate removal during hemodialysis? Proof of concept. Hemodial Int. 2016;20: 601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill Gallant KM, Choi MS, Stremke ER, et al. Evaluation of a radiophosphorus meethod for intestinal phosphorus absorption assessment in humans. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. CONSORT diagram of recruitment.

Figure S2. Individual pharmacokinetic dose curves.

Figure S3. Relationship of vitamin D to phosphorus absorption. (A) 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels versus percentage phosphorus absorption in first period of each study. (B) 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D levels versus percentage phosphorus absorption of placebo arm in study 1 only.

Figure S4. Kinetic model.

Table S1. Numbers of patients with adverse events by event and period (safety population).

Table S2. Biochemical measures: serum P, Ca, Ca × P, intact PTH, and FGF23 at day 13.

Table S3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table S4. Study diets.