Abstract

Background:

Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGlu5) plays an important role in excessive alcohol use. The mGlu5 negative allosteric modulator (NAM) 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP) has been shown to reduce binge drinking in male mice, but less is known about its effect on female mice. The mGlu5/Homer2/Erk2 signaling pathway has been implicated in binge drinking. Here, we sought to determine whether sex difference exists in the effect of MPEP on binge drinking, and whether it relates to changes in the mGlu5/Homer2/Erk2 signaling.

Methods:

We measured the dose-response effect of MPEP on alcohol consumption in male and female mice using the Drinking in the Dark (DID) paradigm to assess potential sex differences. To rule out possible confounds of MPEP on locomotion, we measured effects of MPEP on locomotor activity and drinking simultaneously during DID. Lastly, to test whether MPEP- induced changes in alcohol consumption were related to any changes in Homer2 or Erk2 expression, qPCR was performed using brain tissue acquired from mice that had undergone seven days of DID.

Results:

30 mg/kg MPEP reduced binge alcohol consumption across female and male mice. No sex differences were found for the dose-response relationship. Locomotor activity did not mediate effects of MPEP on alcohol intake, but activity correlated with alcohol intake independent of MPEP. MPEP did not change bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST) or nucleus accumbens mRNA expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in mice with reduced drinking due to MPEP, relative to saline. A positive relationship between alcohol intake and Homer2 expression in the BNST was found.

Conclusions:

MPEP lowered alcohol consumption during DID in male and female C57BL/6 mice without changes in Homer2/Erk2 expression. Locomotor activity did not mediate effects of MPEP on alcohol intake, but it did correlate with alcohol intake. Alcohol intake during DID predicted BNST Homer2 expression. These data provide support for mGlu5 regulation of alcohol consumption across sexes.

Keywords: AUD, MPEP, mGlu5, Sex Differences, C57BL/6

Introduction

Excessive alcohol use is detrimental to individuals, families, and communities, and causes a severe burden of disease, disability and death worldwide (Lim et al., 2012; WHO, 2018). Alcohol use disorder (AUD) refers to a pattern of alcohol use characterized by excessive consumption, inability to stop and a cluster of symptoms including withdrawal, tolerance, and craving. Binge drinking, typically defined as 5 or more alcoholic drinks for males or 4 or more for females on the same occasion at least 1 day in the past month, is particularly problematic (NIAAA, 2004). Although rates of AUD are greater among men (12.4%) than women (4.9%) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), lower body weights, different alcohol metabolism, and greater sensitivity to adverse health effects likely contribute to more severe biopsychosocial consequences in heavy- and binge-drinking women (Thomasson, 1995; Keyes et al, 2008). Approximately 11.4 % of adult women binge drink on average 3 times a month with 6 drinks per binge; the rate goes up to 18% in women of child-bearing age (i.e., ages 18–44 years) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; 2015). Yet, women are often underrepresented in alcohol research. Even though numerous animal models have been developed, the majority of these studies have used mostly male rodents. Together, this highlights the need for inclusive studies investigating mechanisms of AUD.

Much evidence supports the role of the glutamatergic system in alcoholism. Mechanisms of imbalanced glutamate homeostasis have focused on disruptions in connections between prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) that lead to long-lasting drug-seeking behaviors (Kalivas, 2009). Chronic alcohol abuse produces a hyperglutamatergic state that is hypothesized to contribute to alcohol withdrawal and relapse (Koob, 2003). Pharmacological blockade of glutamate signaling is a promising direction in AUD medication development (Olive 2009; Holmes et al., 2013), with metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) being attractive targets. Negative allosteric modulation (NAM) of mGlu5 suppresses various alcohol-related behaviors in rodents including self-administration, withdrawal and reinstatement (Hodge, 2006; Backstrom, 2004; Schroeder, 2008). Hence, a better understanding of the mechanism of mGlu5 NAMs actions is warranted.

One widely used rodent model for binge drinking is “Drinking in the Dark” (DID; Rhodes et al., 2005). 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP) treatment decreases DID alcohol drinking in male mice, but it remains unknown whether the same effect exists in females (Gupta et al., 2008, Cozzoli et al., 2012). It is well-established that binge drinking alters expression of mGlu5-related signaling cascades, which can be regionally sexually divergent (Cozzoli, 2016; Finn et al., 2018). Alcohol intake increases Homer2 expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), NAc, and the amygdala (Campbell et al., 2019; Cozzoli, 2012, 2014a; Szumlinski et al., 2008) and sex differences after binge drinking were reported for this key mGlu5 scaffolding protein (Finn et al., 2018). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) regulation can increase Homer-mGlu5 interactions (Mao and Wang, 2016) and binge drinking changes its expression in the BNST as well as the NAc (Campbell et al., 2019; Finn et al., 2018). Since the mGlu5/Homer2/Erk signaling pathway has been implicated in binge drinking (Campbell et al., 2019), it is important to determine if sexually divergent mechanisms are a factor.

Given the importance of mGluRs in addiction, and the mitigating effect that mGlu5 NAMs have on alcohol drinking behaviors, blockade of these receptors likely causes changes in the expression of mGluR-related genes. MPEP treatment can block cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior and the development of alcohol-induced sensitization, both of which were associated with increased Erk phosphorylation (Schroeder et al., 2008; Stevenson et al., 2019). A transcriptional profiling study suggested that many biological processes altered by MPEP were related to Erk-associated signaling pathways (Gass and Olive, 2018). Yet, few studies have directly tested whether effects of MPEP on alcohol intake are associated with changes in Homer2 and/or Erk2 expression. Furthermore, studies focusing on expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in binge drinking and, critically, sex differences could help elucidate mechanisms of mGlu5 NAMs potential therapeutic actions.

In the present study we used the DID paradigm to assay binge alcohol drinking in male and female mice and MPEP to inhibit mGlu5 signaling. We tested whether: (i) there are sex differences in the dose response for effects of MPEP on alcohol consumption during DID; (ii) MPEP alters Homer2 or Erk2 expression in BNST or NAc in mice with reduced drinking due to MPEP; and whether (iii) changes in these signaling pathways are sexually dimorphic.

Materials and Methods

Animals and General Husbandry

The animals used in this study were male and female C57BL/6NCrl mice purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Strain Code #027) at seven weeks of age. Upon delivery, mice were singly housed with food ad libitum. Water was provided ad libitum via a water bottle except for during the Drinking in the Dark (DID) sessions. The housing room was maintained in a reverse 12-hr dark/light cycle (lights on at 8:00 PM, lights off at 8:00 AM). Animals were given at least one week to habituate to the facility before starting the DID paradigm. All procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs and Drinking Solutions

A 20% ethanol drinking solution for the DID experiments was made with 200 proof ethanol diluted with tap water (v/v) and used within 24 hrs. MPEP (Tocris, Cat. No. 1212, Minneapolis, MN) was dissolved in saline and injected i.p. at 10 ml/kg body weight. A range of doses from 0–30 mg/kg MPEP were used in these studies, based on effective doses of MPEP for reducing drinking in previous studies without having effects on water intake (Gupta et al., 2008).

Drinking in the Dark (DID)

A modified 4-hr version of the previously established DID procedure (Rhodes et al., 2005) was used. Three hrs into the dark cycle, the water bottle was removed from each home cage and replaced by a graduated sipper tube containing 20% ethanol solution. The sipper tubes remained in place for four hrs and volume measurements were taken at zero, two, and four hrs. Volumes were read without removing the sipper tubes from the cages. To control for spillage, an empty cage was set up during every DID session. A sipper tube was put in the cage and volumes were read to ensure the daily spillage was minimal. At the end of the session, the sipper tubes were removed, and water bottles were replaced. Animals were habituated to saline injections before starting DID. Animals also received a saline injection just prior to each DID session to control for the effect of injection itself, except for on the drug testing days when mice received MPEP injections.

Experiment 1: Dose-response for the effect of MPEP on alcohol consumption in DID

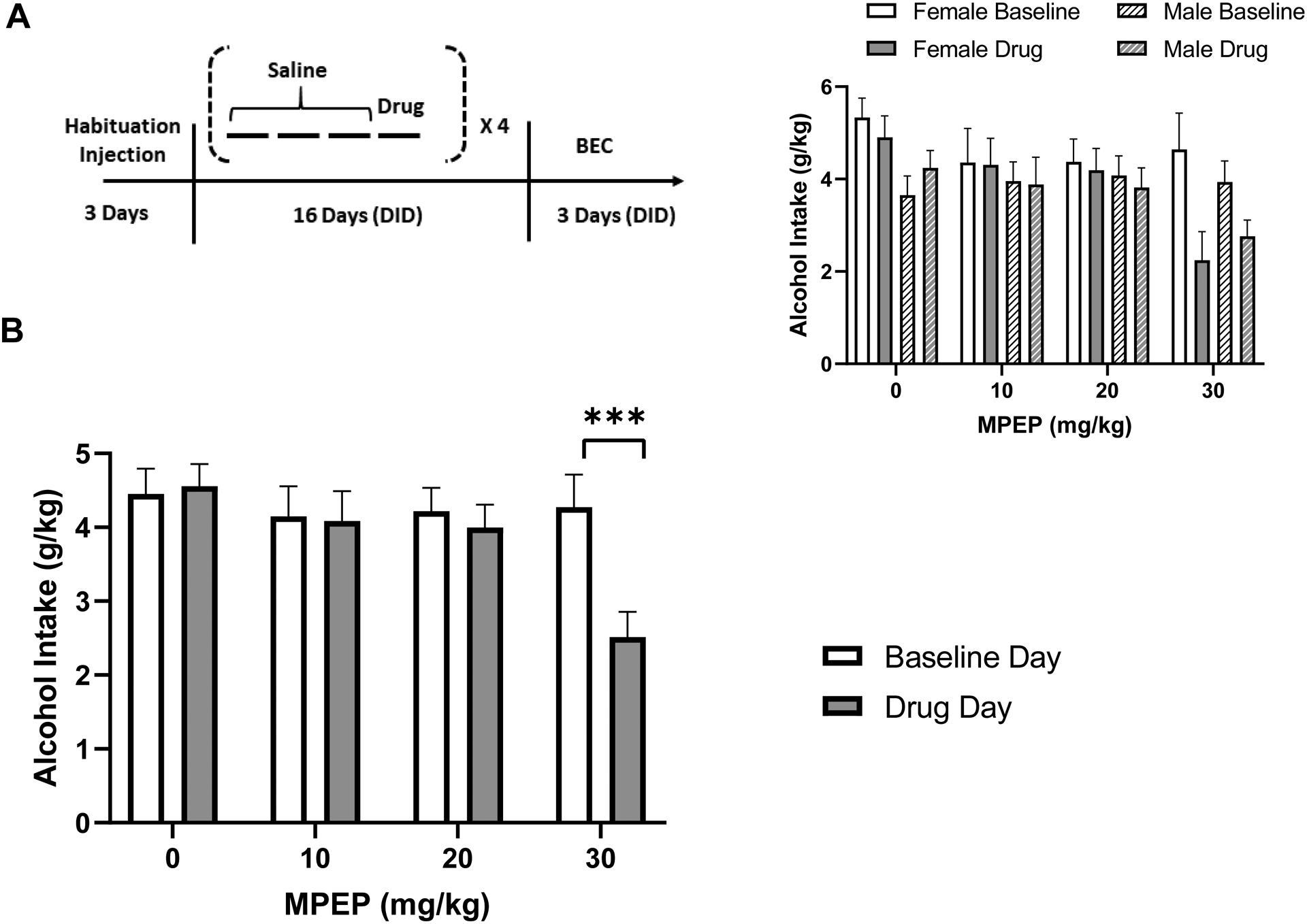

First, we assessed the putative sex- and dose-dependent effects of MPEP on binge alcohol consumption in DID. A within-subject design was used with a total of 23 mice (n = 12 males and 11 females). Animals were habituated to saline injections once daily for three days before starting DID to mitigate effects of injection stressor on alcohol intake (see Fig 1A). In addition to saline injections on each of the preceding three days of DID, every fourth day of DID mice received an injection of MPEP immediately prior to the session. 0, 10, 20, and 30 mg/kg MPEP were tested with the sequence of injections counterbalanced with a Latin-Square design. After the completion of the final MPEP dose the animals continued on DID for three days to test for blood ethanol concentrations (see below).

Fig. 1:

30 mg/kg MPEP reduced alcohol intake in both males and females. (A) Experiment 1 timeline. Animals received three days of habituation injections before starting DID. “Saline” indicates that animals received a saline injection just prior to DID. “Drug” indicates that every fourth day of DID (days four, eight, 12 and 16), animals received an injection of MPEP before DID. Blood ethanol concentration was tested on day 18 or 19 of DID. (B) Alcohol intake (g/kg) in four hrs on the baseline day (with saline injections) versus drug day. MPEP reduced alcohol intake only at 30 mg/kg. Inset: Males and females shown separately. *** p ≤ 0.001. n = 12 males and 11 females.

Experiment 2: Effects of MPEP on locomotion and alcohol consumption

Next, in order to test whether locomotion mediates effects of 30 mg/kg MPEP on drinking, locomotion was measured simultaneously with DID sessions. Forty-six experimentally naïve mice were used in a between-subject design (n = 11–12/sex/drug group) counterbalanced across six cohorts. Animals were habituated to saline injections once daily for three days inside the locomotion testing room prior to DID testing. Animals underwent four days of DID and received saline injections on the first three days and either MPEP (30 mg/kg) or saline injections on the fourth day. Alcohol intake and locomotion were measured during all four DID sessions.

Experiment 3: Effects of MPEP on Homer2 and Erk2 in alcohol drinking animals

Next, we tested whether MPEP alters Homer2 and Erk2 expression in BNST and NAc in animals with MPEP-induced reductions in drinking. A between-subject design was used with 49 experimentally naïve mice (n = 25 females and 24 males; 12–13/sex/drug group). This experiment was carried out in two cohorts with groups counterbalanced across cohorts. Animals were habituated to saline injections once daily for seven days before starting on DID (see Fig 2A). Mice underwent a total of seven days of DID and received saline injections on the first six days and either MPEP (30 mg/kg) or saline injections on the seventh day. The number of days was based on previous reports that used alcohol exposures sufficient to cause changes in expression level of target genes and also sensitive to putative MPEP effects (Cozzoli et al., 2016; Finn et al., 2018). Upon completion of the behavioral experiment, a subset of animals was then selected for qPCR experiments based on: (i) matched alcohol drinking between MPEP and control groups; and (ii) reduced alcohol drinking compared to previous day in the MPEP group. This design aimed to control for the different alcohol consumption between two treatment groups caused by MPEP administration.

Fig. 2:

MPEP did not affect locomotor activity during DID. (A) Experiment 2 timeline. Animals received three days of habituation injections before starting DID. “Saline” indicates that animals received a saline injection just prior to the DID and locomotion session. “Drug” indicates that animals received either saline or MPEP injection just prior to session start. (B) Alcohol intake (g/kg) in four hrs on baseline day versus drug day: animals that received MPEP injection had lower alcohol intake compared to baseline day. (C) Locomotion during DID baseline day versus drug day. (D) Relationship between locomotion and alcohol intake during DID. **p<0.01, versus respective baseline day. n = 11–12/sex/drug group (female control: 12, female MPEP: 12, male control: 11, male MPEP: 11).

Sample Collection

Animals from Experiment 3 were decapitated immediately following the final DID session. Brains were removed, dissected, put on ice, and then sectioned (1 mm thick) using a mouse brain coronal matrix. Punches of BNST and NAc (shell and core together) tissue from both hemispheres were taken with an 18-gauge blunt needle. The coordinates of the brain regions were based on the mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Punches were aimed to center approximately around 1.4 mm AP, ±0.6 mm ML, and −4.3 mm DV for NAc and 0 mm AP, ±0.75 mm ML, and −4.1 mm DV for BNST. Samples were put immediately on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

RNA isolation and purification were conducted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA samples were then transcribed into cDNA with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primers used in this study were (from 5’ to 3’): for Homer2, forward: GGGTCAATCTGGAAGACGTG, Reverse: CGCGTCGACTAGTACGGG (Barua et al., 2014); for Erk2, forward: GGTTGTTCCCAAATGCTGACT, Reverse: CAACTTCAATCCTCTTGTGAGGG (Alcantara et al., 2014). All samples were run in triplicates with GAPDH as the internal control protein. The threshold cycle (Ct) values were obtained and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). All qPCR results were normalized to each female control group.

Locomotor Activity

Locomotor activity was assessed with an infrared photobeam activity system (Med Associates, Inc., St. Albans VT). Every test day, mice were taken into the locomotion testing room and their home cages were placed inside a grid of infrared beams to track activity. Injections were given just prior to each session. Movements were measured based on the number of beams broken, with the unit of locomotion defined as two consecutive beams broken. There were 16 beams in total that were spaced 2.54 centimeters apart.

Blood Ethanol Concentration

Blood ethanol concentration (BEC) was measured in a subset of animals from Experiment 1 at 2–3 days after the last drug test day to confirm their alcohol intake. Blood samples were taken from the retro-orbital sinus immediately after the session. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000×g at 4°C for 10 min to obtain plasma supernatants. The ethanol content of the plasma supernatant was analyzed with an established colorimetric method (Prencipe et al., 1987). Briefly, samples and ethanol standards were diluted with BEC reagent (100 mM KH2PO4; 100 mM K2HPO4; 0.7 mM 4-aminoantopyrine; 1.7 mM chromotropic acid disodium salt; 50 mg/L EDTA; 50 mL/L triton X-100) and added to a 96-well plate. A mixed solution of horseradish peroxidase (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and alcohol oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was then added to each well to start the reaction. The plate was read at approximately 600 nm one hr later.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 8 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) and SPSS 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data are presented as the mean plus or minus the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Outliers were checked using a ROUT method with a maximum false discovery rate of 1%. Alcohol intake, locomotion, and gene expression were assessed using ANOVAs: dose × condition × sex for Experiment 1; drug group × condition × sex for Experiments 2 and 3; and sex × group for Experiment 2, where the ‘condition’ factor refers to the drug day or the previous day as a baseline. Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to resolve the significant interactions. To investigate the relationship between locomotion and alcohol intake and the relationship between alcohol intake and gene expression, multiple linear regression was used with locomotion/alcohol intake, sex, group as independent factors and alcohol intake/gene expression as dependent factors. Additional terms such as the sex × locomotion interaction and the sex × group interaction were added in alternative models to check for model improvement using F tests, but none were identified. Alpha was set to 0.05.

Results

Experiment 1: 30 mg/kg MPEP reduced alcohol intake in both male and female mice

A dose-response experiment using both male and female mice was carried out to investigate potential sex differences in the effect of MPEP on alcohol consumption (Fig. 1A). The mixed-effects ANOVA identified a main effect of dose (F3,63 = 6.203; p< 0.001), a main effect of condition (F1,21 = 7.778; p< 0.05), and a dose × condition interaction (F3,63 = 6.325; p< 0.001). Post hoc tests indicated that MPEP reduced alcohol intake on the drug day compared to baseline day across males and females at the 30 mg/kg (p< 0.005) but not at the 10 or 20 mg/kg doses (Fig. 1B). No effects of sex were identified (Fig. 1B, inset). A mixed-effects ANOVA assessing the effect of each MPEP dose relative to the 0 mg/kg test day, as opposed to the prior baseline day, also identified a main effect of dose (F3,63 = 16.09; p< 0.0001), confirming the result. BEC was measured after the dose-response was finished to confirm intake (mean = 57.55 ± 12.17 mg/dl) which was lower than that typically observed in C57BL6/J mice, in accordance with the literature regarding N versus J substrain alcohol preference and consumption (Mulligan et al., 2008; Ramachandra et al., 2007). A significant correlation was found between alcohol intake and BEC (Pearson r2 = 0.5883, p< 0.001), indicating that measurements were reflective of true intake. In summary, 30 mg/kg MPEP was the only dose tested that reduced alcohol intake, regardless of sex.

Experiment 2: MPEP did not affect locomotor activity during DID

Next, we examined the effect of 30 mg/kg MPEP on locomotor activity during DID to test if locomotor activity accounted for the effect of MPEP on drinking (Fig. 2). First, we confirmed the effect of 30 mg/kg MPEP on alcohol intake across sexes (drug group × condition interaction: F1,42 = 7.038; p< 0.05; post hoc test: p<.01) (Fig. 2B). A main effect of sex (F1,42 = 7.518; p< 0.01) indicated higher intake in females overall. Locomotor activity was assessed during the DID sessions (Fig. 2C). No main effects or interactions with drug group were found, indicating that 30 mg/kg MPEP did not change locomotor activity during DID. A main effect of sex (F1,41 =12.96; p< 0.001) was identified, driven by higher locomotion in female mice. Next, to investigate the relationship between locomotion and alcohol intake, a Spearman correlation was carried out and a significant correlation was found (r = 0.5601, p<0.0001) (Fig. 2D). Despite the appearance of an outlier, it was not detected according to the criteria, and removing it did not substantially affect the relationship (r = 0.5344, p<0.0005). To confirm that this relationship was not due to pooling, a multiple linear regression with sex and drug group as nuisance predictors were carried out. The regression revealed that drug group (t = −2.482; p< 0.05) and locomotor activity (t = 3.497; p< 0.005) significantly predicted drinking. In summary, MPEP did not affect locomotor activity during DID, but drug group and locomotor activity each significantly predicted drinking.

Experiment 3: MPEP did not change the expression of Homer2 or Erk2 in BNST and NAc in mice with MPEP-induced reductions in drinking

Lastly, we investigated the ability of MPEP to alter the expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in BNST and NAc to test if changes in expression of these genes may track with effects of MPEP on drinking (Fig. 3). The mixed-effects ANOVA for alcohol intake revealed a main effect of condition (F1,45 = 6.547; p< 0.05) and a dose × condition interaction (F1,45 = 8.584; p< 0.01) (Fig. 3B). The post hoc test confirmed that 30 mg/kg MPEP again reduced alcohol intake across sexes (p< 0.001). Then, we measured Homer2 and Erk2 expression in NAc. No effects of drug group or sex were identified (p’s>.25) (Fig. 3E, G). Next, we examined the BNST. Homer2 and Erk2 expression in BNST also did not reveal any effects of drug group or sex (p’s>.25) (Fig. 3F, H). Interactions between sex and group were not significant for either Homer2 (F1,26 = 1.935; p = 0.176) or Erk2 (F1,26 = 2.843; p = 0.1038) expression in BNST. These negative findings were not due to frontloading of alcohol consumption, as a further analysis splitting the consumption into two-hr bins revealed that mice drank more during the second two hrs than the first two in the final session, after which tissue was collected (t = 4.525; p<.0005). Overall, these results indicated that MPEP did not change the expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in the BNST or NAc in mice with reduced drinking due to MPEP.

Fig. 3:

MPEP did not change the expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in BNST and NAc in mice with MPEP-induced reductions in drinking. (A) Experiment 3 timeline. Animals received seven days of habituation injections before starting DID. Animals received a saline injection on the first six days of DID and either a saline or MPEP injection on the seventh day just prior to session start. (B) Alcohol intake (g/kg) in the DID session baseline day versus drug day: animals that received MPEP had lower alcohol intake compared to the baseline day. Schematic of tissue punch locations for (C) NAc and (D) BNST. Adapted from the mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). (E)-(H) Target gene expression, control versus MPEP in both males and females. ***p<0.001, versus respective baseline day. For alcohol consumption in Panel B: n = 12–13/sex/drug group (female control: 12, female MPEP: 13, male control: 12, male MPEP: 12). For gene expression in Panels E-H: n = 8 for all groups except for BNST female control and BNST male control, for which n = 7.

Alcohol intake during DID predicted BNST Homer2 expression

Finally, we investigated the relationship between alcohol intake and Homer2 and Erk2 gene expression in BNST and NAc (Fig. 4). A multiple linear regression revealed a significant effect of alcohol intake on BNST Homer2 expression (t = 2.572; p< 0.05) (Fig. 4C), whereas no significant effect of alcohol intake was found on NAc Homer2 (Fig. 4A), NAc Erk2 (Fig. 4B), or BNST Erk2 (Fig. 4D) expression.

Fig. 4:

Alcohol intake during DID predicted BNST Homer2 expression, but not NAc Homer2, NAc Erk2 or BNST Erk2. (A)-(D) Relationship between alcohol intake and target gene expression (collapsed across four groups of animals, control and MPEP in both males and female mice). n = 8 for all groups except for BNST female control and BNST male control, for which n = 7.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effect of mGlu5 negative allosteric modulation on alcohol consumption and tested whether changes in Homer2/Erk2 are associated with this effect. First, we performed a dose-response experiment testing the effect of mGlu5 negative allosteric modulation on DID alcohol consumption in male and female mice. MPEP at 30 mg/kg significantly reduced drinking in mice but no dose-dependent difference between the sexes was found. Next, locomotor assessments during DID sessions suggested that effects of MPEP on alcohol consumption were not attributable to alterations of locomotor activity. Furthermore, Homer2 and Erk2 mRNA levels in BNST and NAc were not altered by MPEP in alcohol drinking animals compared to saline-injected control animals, which does not support a relationship between effects of MPEP on alcohol consumption and these signaling genes. Overall, we found that MPEP lowers alcohol consumption across male and female mice, with no changes found in the Homer2/Erk2 pathway in these select brain regions.

Dose-response of MPEP on binge drinking behavior

First, a dose-response experiment was carried out to test if MPEP changes binge alcohol consumption in both male and female C57BL/6 mice. Among the four doses tested, only 30 mg/kg MPEP, the highest dose tested, lowered the alcohol intake across sexes. This result is consistent with previous findings in male mice (Gupta et al., 2008) and further supports the role for mGlu5 negative allosteric modulation of short term alcohol consumption. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of off target effects of MPEP, which have been reported in humans and rats but at concentrations that exceed the expected brain levels in the present studies (Cosford et al., 2003), and which appear to be somewhat species-dependent; for example, effects of MPEP on NMDAR activity have been observed in rat, but not mouse, cortical culture (Cosford et al., 2003; Lea et al., 2005; Lea and Faden, 2006; O’Leary et al., 2000). Future studies should confirm these findings using a more selective mGlu5 NAM such as MTEP, and should further investigate off target effects of MPEP in mice. No sex differences were identified between doses, suggesting that previous studies testing effects of mGlu5 NAMs on alcohol consumption using only male animals may generalize to females. In contrast to a previous study in males, 20 mg/kg MPEP did not reduce alcohol consumption (Gupta et al., 2008). This discrepancy is likely due to methodological differences such as the DID schedule or the use of a Latin-Square design. Overall, we found that 30 mg/kg MPEP, but not lower doses, decreased binge alcohol intake across sexes.

Locomotor effect of MPEP

After establishing the effective dose of MPEP that lowered drinking, we sought to determine whether MPEP affects locomotor activity during DID, which could confound the reduced drinking effect. Even though many studies have tested MPEP’s locomotor effects, it is unknown how MPEP affects locomotor activity during alcohol drinking (Mcgeehan et al., 2004; Halberstadt et al., 2011; Kinney et al, 2003). In order to test if there is a locomotor effect caused by MPEP that mediates the decrease in alcohol intake, we monitored alcohol intake and locomotor activity simultaneously during DID. While alcohol intake was lowered in mice that received MPEP treatment, there was no change in locomotor activity during this time period. Female mice exhibited higher locomotor activity rates than male mice, but no other sex differences were found. There lacks a consensus in the literature regarding the effect of MPEP on locomotor activity. Some work has shown that locomotion was not changed by 30 mg/kg MPEP (Mcgeehan et al., 2004), while others reported increased locomotion induced by this dose of MPEP (Halberstadt et al., 2011; Sharko and Hodge, 2008). Interestingly, when administered prior to an alcohol injection, as opposed to voluntary consumption as in the present study, 30 mg/kg MPEP has been reported to further reduce 2 g/kg ethanol-induced locomotor suppression (Sharko and Hodge, 2008). These differences are likely related to dose and mode of administration of alcohol. Our results may support 30 mg/kg MPEP having no locomotor effect, although we did not test the effect of MPEP in the absence of alcohol.

Surprisingly, we found that locomotor activity during DID positively correlated with alcohol intake. It has been proposed that some strains of rodents that have high alcohol intake often have high activity levels as well, though no definitive relationship was found (Belknap et al., 1993). Novelty/stress-induced locomotion has been suggested as a predictor of ethanol’s rewarding effects, evidenced by the ability of locomotion to predict future ethanol place-preference conditioning in female mice (Nocjar et al., 1999). A similar relationship was found between novelty-induced locomotor activity and cocaine addiction, which indicates that this phenomenon might be generalizable to other drugs of abuse (Arenas et al, 2014). Future work could test locomotion before exposing animals to alcohol to determine whether individual differences in baseline locomotion predict future binge drinking behavior. Such data would be relevant for determining if locomotor activity is useful as a biomarker for excessive alcohol use in animal models of binge drinking. In summary, locomotor activity did not mediate the mitigating effect of MPEP on alcohol consumption in male or female mice, and locomotor activity during DID correlated with alcohol intake.

Homer2 and Erk2 in binge drinking

Next, we tested the hypothesis that when MPEP lowers alcohol intake, MPEP alters Homer2 and/or Erk2 expression. This hypothesis was based on a growing body of evidence supporting the role of the Homer2/Erk2 pathway in binge drinking (Agoglia, 2015; Campbell et al., 2019; Szumlinski et al., 2008) and the notion that MPEP likely changes these genes. Mice that reduced alcohol consumption following MPEP injection did not have different mRNA expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in the BNST or NAc relative to animals that received saline but had matched alcohol intake. No sex effect was revealed either. This result aligns with a previous study in which brain tissue of NAc was collected after 30 days of withdrawal from alcohol from female mice that were repeatedly given MTEP during binge drinking sessions (Cozzoli, 2014b). No effects of MTEP on Homer2 and Erk2 were found in this study either. Future work could manipulate expression of these genes directly or examine other brain regions and protein levels as well as Erk phosphorylation, which has been implicated in several alcohol-related behaviors, including binge drinking (Agoglia, 2015). Future studies could further elucidate this point by including water drinking control groups. Overall, these findings suggest that MPEP may not reduce Homer2 or Erk expression in BNST and NAc in animals with MPEP-induced reductions in drinking.

Interestingly, alcohol intake during DID significantly correlated with BNST Homer2 expression. This finding is consistent with previous work that identified upregulated Homer2 protein expression in BNST of DID animals compared to water-drinking controls (Campbell et al., 2019). Our study builds on this finding, revealing a positive relationship between alcohol intake and Homer2 gene expression. This result indicates that greater alcohol intake is related to higher Homer2 expression, which suggests the sensitivity of Homer2 expression to the level of alcohol consumption. This finding supports the role of BNST Homer2 in excessive alcohol use. However, we did not find any relationship between alcohol intake and NAc Homer2. Despite the well-established role of the Homer2 gene in NAc, the previous literature regarding how alcohol consumption affects Homer2 expression has reported contradictory results. Both lowered and increased NAc Homer2 expression caused by alcohol consumption have been reported in male mice, while unchanged expression was observed in females (Cozzoli et al., 2016; Finn et al., 2018). However, reports of Homer2 protein levels are more consistent across studies (Cozzoli et al., 2009; Cozzoli et al., 2012; Beckley et al., 2016), suggesting that discrepancies between studies regarding gene expression could be due to time course. Overall, our data emphasizes the role for BNST Homer2 in alcohol consumption.

As for the relationship between alcohol consumption and Erk2 levels, binge drinking has been shown to reduce NAc Erk2 mRNA in male and female mice, whereas Erk2 protein phosphorylation in BNST was increased in males (Campbell et al., 2019; Finn et al., 2018; Beckley et al., 2016). Yet we did not detect any relationship between alcohol intake and Erk2 expression, consistent with a lack of change in overall protein levels in previous work (Campbell et al., 2019). Differences in binge drinking paradigms and durations likely contribute to the discrepancies between studies, in addition to the inability to assess phosphorylation state in qPCR studies. Future studies could use models of alcohol intake on an extended timeframe to assess whether gene expression is differentially altered after long term alcohol exposure. In summary, our data suggests that Erk2 mRNA expression was not sensitive to alcohol intake in the BNST or NAc. Future work focused on Erk2 regulation could examine protein levels as well as phosphorylation states in other brain regions.

Conclusion

In summary, MPEP attenuated alcohol drinking at a dose of 30 mg/kg across male and female C57BL/6 mice. This finding further supports the role of mGlu5 in binge drinking behaviors and the potential for mGlu5 NAMs as therapeutics in both females and males with AUD. Locomotor activity did not mediate effects of MPEP on alcohol intake but correlated with alcohol intake independent of MPEP. MPEP did not change the mRNA expression of Homer2 and Erk2 in the BNST or NAc in mice with reduced drinking due to MPEP, relative to animals that received saline, suggesting that MPEP may not alter Homer2 and Erk2 expression when reducing alcohol consumption. Alcohol intake during DID predicted BNST Homer2 expression. Overall, these results suggest that MPEP lowers binge drinking across male and female mice, but we did not find evidence of MPEP-related changes in the Homer2/Erk2 pathway. Future studies could investigate other glutamatergic genes to elucidate mechanisms underlying the pharmacological effects of mGlu5 NAMs on binge alcohol consumption. Female subjects warrant inclusion in studies that examine the role of sex in the pathophysiology of AUD.

Funding information:

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA012870). Additional support from the Charles B.G. Murphy Fund, and the State of CT Department of Mental Health Services. GH was supported by The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China. SLT was supported by TL1 TR001864 and T32 MH014276. This publication does not express the view of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services or the State of Connecticut. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Accessibility Statement: Data are available upon request from the authors.

References

- Agoglia AE, Sharko AC, Psilos KE, Holstein SE, Reid GT, Hodge CW, 2015. Alcohol Alters the Activation of ERK1/2, a Functional Regulator of Binge Alcohol Drinking in Adult C57BL/6J Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 39, 463–475. 10.1111/acer.12645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara LF, Warren BL, Parise EM, Iñiguez SD, Bolaños-Guzmán CA, 2014. Effects of psychotropic drugs on second messenger signaling and preference for nicotine in juvenile male mice. Psychopharmacology 231, 1479–1492. 10.1007/s00213-014-3434-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. ed. American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas MC, Daza-Losada M, Vidal-Infer A, Aguilar MA, Miñarro J, Rodríguez-Arias M, 2014. Capacity of novelty-induced locomotor activity and the hole-board test to predict sensitivity to the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. Physiology & Behavior 133, 152–160. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström P, Bachteler D, Koch S, Hyytiä P, Spanagel R, 2004. mGluR5 Antagonist MPEP Reduces Ethanol-Seeking and Relapse Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 921–928. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua S, Kuizon S, Chadman KK, Flory MJ, Brown W, Junaid MA, 2014. Single-base resolution of mouse offspring brain methylome reveals epigenome modifications caused by gestational folic acid. Epigenetics & Chromatin 7, 3. 10.1186/1756-8935-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckley JT, Laguesse S, Phamluong K, Morisot N, Wegner SA, Ron D, 2016. The First Alcohol Drink Triggers mTORC1-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity in Nucleus Accumbens Dopamine D1 Receptor Neurons. J. Neurosci 36, 701–713. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2254-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Young ER, 1993. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology 112, 503–510. 10.1007/BF02244901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RR, Domingo RD, Williams AR, Wroten MG, McGregor HA, Waltermire RS, Greentree DI, Goulding SP, Thompson AB, Lee KM, Quadir SG, Jimenez Chavez CL, Coelho MA, Gould AT, von Jonquieres G, Klugmann M, Worley PF, Kippin TE, Szumlinski KK, 2019. Increased Alcohol-Drinking Induced by Manipulations of mGlu5 Phosphorylation within the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis. J. Neurosci 39, 2745–2761. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1909-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking Among Women of Childbearing Age — United States, 2011–2013 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6437a3.htm (accessed 12.6.20).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. Vital Signs: Binge Drinking Prevalence, Frequency, and Intensity Among Adults — United States, 2010 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6101a4.htm (accessed 12.6.20). [PubMed]

- Cosford NDP, Tehrani L, Roppe J, Schweiger E, Smith ND, Anderson J, Bristow L, Brodkin J, Jiang X, McDonald I, Rao S, Washburn M, Varney MA, 2003. 3-[(2-Methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]-pyridine: a potent and highly selective metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptor antagonist with anxiolytic activity. J. Med. Chem 46, 204–206. 10.1021/jm025570j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli DK, Courson J, Caruana AL, Miller BW, Greentree DI, Thompson AB, Wroten MG, Zhang P-W, Xiao B, Hu J-H, Klugmann M, Metten P, Worley PF, Crabbe JC, Szumlinski KK, 2012. Nucleus Accumbens mGluR5-Associated Signaling Regulates Binge Alcohol Drinking Under Drinking-in-the-Dark Procedures. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 36, 1623–1633. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01776.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli DK, Courson J, Wroten MG, Greentree DI, Lum EN, Campbell RR, Thompson AB, Maliniak D, Worley PF, Jonquieres G, Klugmann M, Finn DA, Szumlinski KK, 2014a. Binge Alcohol Drinking by Mice Requires Intact Group1 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Signaling Within the Central Nucleus of the Amygdale. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 435–444. 10.1038/npp.2013.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli DK, Goulding SP, Zhang PW, Xiao B, Hu J-H, Ary AW, Obara I, Rahn A, Abou-Ziab H, Tyrrel B, Marini C, Yoneyama N, Metten P, Snelling C, Dehoff MH, Crabbe JC, Finn DA, Klugmann M, Worley PF, Szumlinski KK, 2009. Binge Drinking Upregulates Accumbens mGluR5–Homer2–PI3K Signaling: Functional Implications for Alcoholism. J. Neurosci 29, 8655–8668. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5900-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli DK, Kaufman MN, Nipper MA, Hashimoto JG, Wiren KM, Finn DA, 2016. Functional regulation of PI3K-associated signaling in the accumbens by binge alcohol drinking in male but not female mice. Neuropharmacology 105, 164–174. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzoli DK, Strong-Kaufman MN, Tanchuck MA, Hashimoto JG, Wiren KM, Finn DA, 2014b. The Effect of mGluR5 Antagonism During Binge Drinking on Subsequent Ethanol Intake in C57BL/6J Mice: Sex- and Age-Induced Differences. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 38, 730–738. 10.1111/acer.12292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Hashimoto JG, Cozzoli DK, Helms ML, Nipper MA, Kaufman MN, Wiren KM, Guizzetti M, 2018. Binge Ethanol Drinking Produces Sexually Divergent and Distinct Changes in Nucleus Accumbens Signaling Cascades and Pathways in Adult C57BL/6J Mice. Front Genet 9, 325. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Olive MF, 2008. Transcriptional profiling of the rat frontal cortex following administration of the mGlu5 receptor antagonists MPEP and MTEP. Eur. J. Pharmacol 584, 253–262. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Syed YM, Revis AA, Miller SA, Martinez M, Cohn KA, Demeyer MR, Patel KY, Brzezinska WJ, Rhodes JS, 2008. Acute Effects of Acamprosate and MPEP on Ethanol Drinking-in-the-Dark in Male C57BL/6J Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 32, 1992–1998. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AL, Lehmann-Masten VD, Geyer MA, Powell SB, 2011. Interactive effects of mGlu5 and 5-HT2A receptors on locomotor activity in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 215, 81–92. 10.1007/s00213-010-2115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Miles MF, Sharko AC, Stevenson RA, Hillmann JR, Lepoutre V, Besheer J, Schroeder JP, 2006. The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP selectively inhibits the onset and maintenance of ethanol self-administration in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 183, 429–438. 10.1007/s00213-005-0217-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Spanagel R, Krystal JH, 2013. Glutamatergic targets for new alcohol medications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 229, 539–554. 10.1007/s00213-013-3226-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, 2009. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10, 561–572. 10.1038/nrn2515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS, 2008. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 93, 21–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney GG, Burno M, Campbell UC, Hernandez LM, Rodriguez D, Bristow LJ, Conn PJ, 2003. Metabotropic Glutamate Subtype 5 Receptors Modulate Locomotor Activity and Sensorimotor Gating in Rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306, 116–123. 10.1124/jpet.103.048702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, 2003. Alcoholism: allostasis and beyond. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 27, 232–243. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057122.36127.C2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea PM, Faden AI, 2006. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Subtype 5 Antagonists MPEP and MTEP. CNS Drug Rev. 12, 149–166. 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00149.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea PM, Movsesyan VA, Faden AI, 2005. Neuroprotective activity of the mGluR5 antagonists MPEP and MTEP against acute excitotoxicity differs and does not reflect actions at mGluR5 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol 145, 527–534. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, AlMazroa MA, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, Chafe Z, Charlson F, Chen H, Chen JS, Cheng AT-A, Child JC, Cohen A, Colson KE, Cowie BC, Darby S, Darling S, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dentener F, Des Jarlais DC, Devries K, Dherani M, Ding EL, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Edmond K, Ali SE, Engell RE, Erwin PJ, Fahimi S, Falder G, Farzadfar F, Ferrari A, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Fowkes FGR, Freedman G, Freeman MK, Gakidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannucci E, Gmel G, Graham K, Grainger R, Grant B, Gunnell D, Gutierrez HR, Hall W, Hoek HW, Hogan A, Hosgood HD, Hoy D, Hu H, Hubbell BJ, Hutchings SJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacklyn GL, Jasrasaria R, Jonas JB, Kan H, Kanis JA, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Khang Y-H, Khatibzadeh S, Khoo J-P, Kok C, Laden F, Lalloo R, Lan Q, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Li Y, Lin JK, Lipshultz SE, London S, Lozano R, Lu Y, Mak J, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Marcenes W, March L, Marks R, Martin R, McGale P, McGrath J, Mehta S, Memish ZA, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Micha R, Michaud C, Mishra V, Hanafiah KM, Mokdad AA, Morawska L, Mozaffarian D, Murphy T, Naghavi M, Neal B, Nelson PK, Nolla JM, Norman R, Olives C, Omer SB, Orchard J, Osborne R, Ostro B, Page A, Pandey KD, Parry CD, Passmore E, Patra J, Pearce N, Pelizzari PM, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pope D, Pope CA, Powles J, Rao M, Razavi H, Rehfuess EA, Rehm JT, Ritz B, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Romieu I, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Roy A, Rushton L, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Sapkota A, Seedat S, Shi P, Shield K, Shivakoti R, Singh GM, Sleet DA, Smith E, Smith KR, Stapelberg NJ, Steenland K, Stöckl H, Stovner LJ, Straif K, Straney L, Thurston GD, Tran JH, Van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Veerman JL, Vijayakumar L, Weintraub R, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams W, Wilson N, Woolf AD, Yip P, Zielinski JM, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, 2012. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380, 2224–2260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L-M, Wang JQ, 2016. Synaptically Localized Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases: Local Substrates and Regulation. Mol Neurobiol 53, 6309–6315. 10.1007/s12035-015-9535-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgeehan AJ, Janak PH, Olive MF, 2004. Effect of the mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) on the acute locomotor stimulant properties of cocaine, D-amphetamine, and the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 174, 266–273. 10.1007/s00213-003-1733-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan MK, Ponomarev I, Boehm SL, Owen JA, Levin PS, Berman AE, Blednov YA, Crabbe JC, Williams RW, Miles MF, Bergeson SE, 2008. Alcohol trait and transcriptional genomic analysis of C57BL/6 substrains. Genes, Brain and Behavior 7, 677–689. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocjar C, Middaugh LD, Tavernetti M, 1999. Ethanol Consumption and Place-Preference Conditioning in the Alcohol-Preferring C57BL/6 Mouse: Relationship with Motor Activity Patterns. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 23, 683–692. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DM, Movsesyan V, Vicini S, Faden AI, 2000. Selective mGluR5 antagonists MPEP and SIB-1893 decrease NMDA or glutamate-mediated neuronal toxicity through actions that reflect NMDA receptor antagonism. Br. J. Pharmacol 131, 1429–1437. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, 2009. Metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands as potential therapeutics for addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2, 83–98. 10.2174/1874473710902010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ, 2001. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prencipe L, Iaccheri E, Manzati C, 1987. Enzymic ethanol assay: a new colorimetric method based on measurement of hydrogen peroxide. Clinical Chemistry 33, 486–489. 10.1093/clinchem/33.4.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra V, Phuc S, Franco AC, Gonzales RA, 2007. Ethanol Preference Is Inversely Correlated With Ethanol-Induced Dopamine Release in 2 Substrains of C57BL/6 Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 31, 1669–1676. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK,Finn DA, Crabbe JC, 2005. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiology & Behavior 84, 53–63. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ, 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3, 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JP, Spanos M, Stevenson JR, Besheer J, Salling M, Hodge CW, 2008. Cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior is associated with increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation in specific limbic brain regions: blockade by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropharmacology 55, 546–554. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharko AC, Hodge CW, 2008. Differential modulation of ethanol-induced sedation and hypnosis by metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32, 67–76. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00554.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RA, Hoffman JL, Maldonado-Devincci AM, Faccidomo S, Hodge CW, 2019. MGluR5 activity is required for the induction of ethanol behavioral sensitization and associated changes in ERK MAP kinase phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens shell and lateral habenula. Behav. Brain Res 367, 19–27. 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Ary AW, Lominac KD, 2008. Homers regulate drug-induced neuroplasticity: Implications for addiction. Biochemical Pharmacology, Addiction Special Issue 75, 112–133. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson HR, Beard JD, Li T-K, 1995. ADH2 Gene Polymorphisms Are Determinants of Alcohol Pharmacokinetics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 19, 1494–1499. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Management of Substance Abuse Team, 2018. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018.