Abstract

Background

In spring 2020, U.S. universities closed campuses to limit the transmission of COVID‐19, resulting in an abrupt change in residence, reductions in social interaction, and in many cases, movement away from a heavy drinking culture. The present mixed‐methods study explores COVID‐19‐related changes in college student drinking. We characterize concomitant changes in social and location drinking contexts and describe reasons attributed to changes in drinking.

Methods

We conducted two studies of the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on drinking behavior, drinking context, and reasons for both increases and decreases in consumption among college students. Study 1 (qualitative) included 18 heavy‐drinking college students (M age = 20.2; 56% female) who completed semi‐structured interviews. Study 2 (quantitative) included 312 current and former college students who reported use of alcohol and cannabis (M age = 21.3; 62% female) and who completed an online survey.

Results

In both studies, COVID‐19‐related increases in drinking frequency were accompanied by decreases in quantity, heavy drinking, and drunkenness. Yet, in Study 2, although heavier drinkers reduced their drinking, among non‐heavy drinkers several indices of consumption increased or remained stable . Both studies also provided evidence of reductions in social drinking with friends and roommates and at parties and increased drinking with family. Participants confirmed that their drinking decreased due to reduced social opportunities and/or settings, limited access to alcohol, and reasons related to health and self‐discipline. Increases were attributed to greater opportunity (more time) and boredom and to a lesser extent, lower perceived risk of harm and to cope with distress.

Conclusion

This study documents COVID‐19‐related changes in drinking among college student drinkers that were attributable to changes in context, particularly a shift away from heavy drinking with peers to lighter drinking with family. Given the continued threat of COVID‐19, it is imperative for researchers, administrators, and parents to understand these trends as they may have lasting effects on college student drinking behaviors.

Keywords: COVID, Pandemic, Alcohol, Context, College

This mixed‐method study explored COVID‐19‐related changes in college student drinking using a combination of interviews (n=18) and online surveys (n=312). Increases in drinking frequency were accompanied by decreases in quantity, heavy drinking, and drunkenness, especially among heavier drinkers. Drinking reductions were attributable to changes in context, particularly shifts from social drinking with peers to lighter drinking with family; participants also reported changes in access, opportunity, and risk of harm. These COVID‐19‐related changes may have lasting effects on college student drinking.

In 2020, the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) spread rapidly across the world, with 99 million confirmed cases worldwide and 25 million in the United States as of January 2021 (Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center, 2021). In March 2020, the threat of COVID‐19 prompted U.S. universities to limit the disease’s transmission by closing campus for the semester, postponing campus events, and ultimately shifting to fully remote instruction (Sahu, 2020). These university closings led to changes in living situation that, coupled with social distancing measures, impacted level of stress, reduced social interaction, and led to poorer mental health (Elmer et al., 2020). College students left a relatively insular campus environment characterized by academic rigor and social interaction, and in many cases, heavy drinking.

Macrolevel investigations of COVID‐19‐related changes on drinking indicate that off‐premise outlet (liquor stores) and online alcohol purchases increased, while on‐premise outlet (restaurants, bars) purchases substantially declined (Nielsen, 2020). Epidemiological findings on COVID‐19‐related drinking changes are mixed, showing both increases and decreases in use (Avery et al., 2020; Holmes, 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Rolland et al., 2020). Research with adolescents tends to support declines in heaviness of alcohol use but increases in drinking frequency (Dumas et al., 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2020). Declines in heavy and problem drinking were particularly evident among Australian drinkers aged 18 to 25 (Callinan et al. 2020). Among college students specifically, the limited work to date has indicated decreases in average number of drinks consumed/week after lockdown in a sample of Belgian students (Bollen et al., 2021) and increases in both frequency and quantity of alcohol use in the United States (Lechner et al., 2020). Drinking increased particularly for those students in Russia and Belarus under quarantine/self‐isolation conditions (Gritsenko et al., 2020). Those who reported drinking greater quantities during the pandemic were previously heavier drinkers (Holmes, 2020; Weerakoon et al., 2020).

Understanding COVID‐19‐related Changes in Alcohol Involvement

We draw from recent COVID‐19 work as well as the broader literature on motives/reasons for drinking to inform our understanding of COVID‐related change in drinking behavior.

Distress

One risk factor that may prompt COVID‐19‐related increases in drinking is increased psychological distress (Jackson et al., 2020; Rehm et al., 2020). Emerging studies show associations between anxiety, depression, and psychological distress with drinking during the pandemic among college students (Gritsenko et al., 2020; Lechner et al., 2020), adolescents (Dumas et al., 2020), and adults (Avary et al., 2020; Callinan et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2020; Rolland et al., 2020). Social isolation and reduced social support may lead to increased drinking (Lechner et al., 2020; Wardell et al., 2020) and endanger attempts at sobriety (The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2020). Indeed, motives to drink to reduce distress or negative affect (coping motives) were associated with increased alcohol consumption relative to pre‐COVID levels in adults (Wardell et al., 2020) and Belgian college students (Bollen et al., 2021).

Access/Opportunity

Reductions in drinking may be a function of reduced availability of alcohol due to on‐premise outlet closures and fewer social sources of alcohol (Rehm et al., 2020). At the same time, drinking may increase due to reduced “opportunity costs” associated with use; that is, there is a shift in the relative value of immediate reinforcement from drinking vs. costs of substance use such as interpersonal or academic problems (Acuff et al., 2020). For example, remote learning and job loss may increase free time, remove the need for sober drivers, and reduce consequences of visible hangover symptoms; job loss may likewise increase free time and reduce responsibilities, although it may result in less disposable income for purchasing alcohol. Alcohol use also may increase due to constraints on rewarding alternatives to alcohol use especially alternative activities that are incompatible with substance use, such as school clubs and team sports (Acuff et al., 2020). In the only study on reasons for COVID‐related changes in substance (cannabis) use behavior, self‐reported reductions were attributed to decreased availability and fewer opportunities for social interaction, and increases were attributed to more time, fewer responsibilities, and boredom (Chu et al, 2020).

Change in Context

A departure from a social context where alcohol is commonly available or consumed may actually be protective for college students, who tend to drink in social situations. Young adult drinking typically occurs in social settings such as parties (Beck et al., ,2008, 2013; Lipperman‐Kreda et al., 2015), in public settings (Keough et al., 2015; Kypri et al., 2007), and rarely alone (Simons et al., 2005), and drinking typically takes place in groups of friends (Baer, 2002; Beck et al., 2008). College students are more likely to drink in high quantities when with peers (Thrul et al., 2017) and often affiliate with heavily‐drinking peer networks that include close friends who serve as “drinking buddies” (Lau‐Barraco and Linden, 2014; Reifman et al., 2006). Thus, it is possible that declines in college student drinking, especially excessive drinking, would be observed following campus closure due to reduced social interaction. Indeed, in a Belgian college student sample, drinking for social reasons was associated with COVID‐related changes in alcohol consumption, although this depended on type of drinker: Social motives were associated with lower consumption during lockdown among heavy drinkers but higher consumption among lighter drinkers (Bollen et al., 2021).

A study conducted in a sample of Canadian high school students characterizing COVID‐19‐related changes in the social context of drinking (Dumas et al., 2020) indicated heavy drinking declined but engagement in solitary drinking and drinking with parents increased between the 3 weeks before and since the COVID‐19 crisis, consistent with college student heavy drinking as a socially motivated behavior. In contrast, drinking frequency was higher when drinking with parents versus alone or with friends. Our group recently demonstrated that moving from living with peers to parents following COVID‐related campus closure was associated with reductions in quantity and frequency of consumption (White et al., 2020a,b). The present work builds on this earlier study by examining additional indices of drinking and providing a much more comprehensive examination of context, both physical and social, as well as examining reasons for changes in drinking.

Cognitive Reasons for Change

We draw from literature on reasons for limiting or abstaining drinking (RALD; Epler et al., 2009) to identify additional putative reasons for COVID‐related drinking change. Specifically, we explore whether drinking changes are associated with reasons related to upbringing (e.g., family disapproval, rules against drinking), need for self‐control, or risk of harm (e.g., drinking is bad for my health).

Overview

We used a mixed‐methods approach to explore COVID‐19‐related changes in college student drinking, using data gathered from 2 existing studies of U.S. college student drinkers. Study 1 involved qualitative data (individual interviews) among heavy episodic drinkers, and Study 2 involved quantitative data (retrospective online surveys) among drinkers. We characterized social and location contexts of drinking prior to campus closure (“preclosure”) compared to following campus closure (“postclosure”). Self‐reported reasons examined for COVID‐related drinking change beyond change in context included access/opportunity, coping with distress, and cognitive reasons for limiting or abstaining drinking, including those related to upbringing, self‐control, and risk of harm. By using 2 separate samples and methodological approaches, we attempted to obtain a comprehensive understanding of COVID‐19‐related changes in drinking. In both samples, we considered frequency and quantity of alcohol use; in the quantitative sample, we examined whether changes in use were more pronounced in preclosure heavier users. Additionally, in both samples, we characterized COVID‐19‐related changes in contexts.

Study 1 Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants (n = 18, 56% women, ages 18 to 25) were recruited for a pilot study examining feasibility and acceptability of a mobile intervention for heavy drinking (Merrill et al., 2021). Students were recruited from a private institution located in an urban setting in the Northeastern United States, where 94% of students are enrolled full‐time. All first‐year students and 74% of the entire undergraduate population live on campus, and the student body is racially/ethnically diverse (42% White). Undergraduate students who were weekly heavy episodic drinkers (HED; 4+[women]/5+[men] drinks in a single sitting) over the past month and had at least 1 past‐month negative consequence1 were enrolled. Baseline descriptives are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information

| Study 1 (N = 18) (Qualitative) | Study 2 (N = 312) (Quantitative) | |

|---|---|---|

| n/% or Mean (SD) | ||

| Age |

20.2 (1.20) range 18‐22 |

21.3 (0.82) range 19‐26 |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Male | 8 (44%) | 115 (38%) |

| Female | 10 (56%) | 191 (62%) |

| Gender Identity (check all) | ||

| Male only | 8 (44%) | 116 (37%) |

| Female only | 8 (44%) | 191 (61%) |

| Nonbinary a | 2 (12%) | 5 (2%) |

| Year in School b | ||

| First year | 4 (22%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sophomore | 5 (28%) | 2 (1%) |

| Junior | 4 (22%) | 124 (41%) |

| Senior | 5 (28%) | 156 (56%) |

| >Senior | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1 (6%) | 40 (13%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 12 (67%) | 205 (67%) |

| Asian | 5 (28%) | 39 (13%) |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 12 (4%) |

| Multiracial | 0 (0%) | 27 (9%) |

| Other | 1 (6%) | 22 (7%) |

| Drinking Behavior c | ||

| Average drinks on typical drinking day d | 5.08 (1.83) | 3.78 (2.25) |

| Peak drinks on typical drinking day d | 9.31 (2.87) | 4.46 (3.14) |

| Total drinks on a typical week | 15.44 (7.20) | 10.95 (9.74) |

| HED days in past 30 days | 6.56 (3.18) | |

| Days drunk in past 30 days | 3.48 (0.92) | |

The nonbinary category includes genderqueer, trans male/trans man; trans female/trans woman; and fluid male/female.

For Study 2 participants, prevalence based on the 281 still in school.

Study 2 values are from the preclosure assessment.

Single item assessed at baseline in Study 1.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Procedures

Beginning March 10, 2020, participants were recruited using advertisements on and around campus and in the university’s morning email. A total of 219 interested participants completed an online screener; 43 were eligible, and the first 25 of those were invited to participate (to achieve our target sample of 18 to 20). Eighteen participants enrolled in the study and completed videoconference‐based study orientation sessions in small groups, between March 20 and 23, 20202. This session included (i) completion of informed consent, sent via an online form, (ii) an online baseline survey assessing demographics and past‐month drinking behavior, and (iii) training and practice on the use of a daily survey and feedback tool. Participants were informed that the goal of the study was not an attempt to change their drinking behavior, but that we simply sought feedback on how best to refine our intervention prototype during ongoing development. Participants received a $25 gift card for completing the baseline session. Next, daily surveys and mobile‐delivered personalized feedback reports were administered for 28 days (March 30 to April 26, 2020)3. However, the daily data and feedback reports were not of focus in the present study.

Relevant to the present study, following completion of the 28‐day intervention participants completed a 45‐min individual interview via videoconference. The primary goal was to get feedback on the intervention feasibility and suggestions for improving its implementation (not as an outcome evaluation of intervention efficacy); however, questions on the impact of COVID‐19 (see Measures) were added for the present investigation. Interviews took place between April 27 and 30, 2020, approximately 6 weeks after campus closure. All 18 participants completed the interview and were entered into a raffle for a $100 gift card.

Measures

At baseline, participants completed self‐report measures of demographics and drinking behavior. After presentation of standard drink definitions, past 30‐day alcohol use was assessed with 3 items for descriptives: typical drinks per drinking day, peak drinks, and number of HED days. Additionally, participants completed a weekly grid (Daily Drinking Questionnaire; DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) entering number of standard drinks for each day in typical week, used to calculate drinks per week.

The majority of postintervention interviews were delivered by 2 trained graduate students, with the minority delivered by the second author. Interviews began with reminders that interviewers were not judging the participant’s drinking behavior and that students could choose to refuse to answer any question. Interviews were semistructured, beginning with a focus on how COVID‐19 had impacted participants. This included the following key questions (and follow‐up probes): (i) What impact has the COVID‐19 pandemic had on your daily life? (ii) How have any of these changes impacted your drinking? (iii) How has the context of your drinking, such as who you’re drinking with or where you drink, changed due to any of these changes? (iv) How, if at all, have your reasons for drinking changed due to any of these other changes? The remainder of the interview centered on establishing acceptability of the mobile intervention, and was not relevant for the present investigation (e.g., What kinds of reactions did you have to viewing your feedback?).

Qualitative Analyses

Each interview was transcribed verbatim. The initial coding structure was developed directly from the interview agenda; a deductive code represented each key question area (i) impacts on daily life; (ii) change in drinking behavior; (iii) reasons for drinking. One coder did a first pass at coding, a process during which 3 additional subcodes under “impacts on daily life” emerged (inductively) and were added to the codebook. These included (1.1) change in living situation, (1.2) change in social life, and (1.3) psychological impact. The first coder went back to apply these emergent codes to previously coded transcripts. Subsequently, a second coder independently coded the data using the final codebook. The 2 coders then met to resolve discrepancies, bringing codes into 100% agreement. Prior to resolving discrepancies, rate of agreement was 92% (i.e., passages coded identically by the 2 coders). Next, we took an “applied thematic analysis” approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Guest et al., 2011). This entailed reviewing all transcript passages within each code, and writing summaries of these codes to describe the most commonly reported experiences. As such, the raw transcript data that had been organized topically (by code) became the themes reported in our results and Table 2. The 2 coders ultimately agreed upon all final themes.

Table 2.

Qualitative Themes and Representative Quotes

| Representative Quotes | ID, sex |

|---|---|

| Theme 1 Students’ drinking frequency increased, while their drinking quantity decreased | |

| Instead of like drinking a lot, like multiple drinks on the weekend, I’ll have like one drink per night. I’ll like have a beer with dinner, instead of like 4 mixed drinks before I go to a party or like at a party – so it’s definitely changed – It’s been more spaced out and more low key – I definitely haven’t been getting drunk. | 1018, female |

| I’m doing more like one beer a night…. It’s more casual now and less with the intention of getting drunk. More like, “I have a few beers in the fridge, so I’m going to have a beer”. So it feels more distributed than the high concentration drinking nights of the semester. There is nothing really to be drinking for now I guess. | 1005, male |

| I definitely drink a lot less now than I did before. At school, I drink as a social thing. At home, there’s no reason for me to drink. Occasionally I would have a drink with my parents, but that’s all the drinking I did. | 1003, female |

| It’s definitely changed my drinking habits. I still will like occasionally have something to drink but it definitely was less often. Probably on a night that I’m going out, it would be about 8 or 9 drinks, but that would be spread out over a couple of hours – some at the pregame and some at the party. Whereas now it’s probably like 4 or 5. | 1012, male |

| Theme 2: The type of alcohol students consumed changed, from hard liquor to wine and/or beer. | |

| I’m drinking a lot less hard alcohol and more wine and beer. | 1004, female |

| …less hard alcohol for sure. Definitely more wine and beer. I think because normally I would drink more shots of liquor and hard alcohol at like outdoor gathering functions and because those aren’t really available anymore, I just have more at home where I drink more casually, slowly, more with just like eating dinner. | 1010, male |

| My drinking changed a little bit in terms of the type of alcohol I was using, especially since I focused more on drinking wine. I have been sort of re‐evaluating my drinking and sort of seeing what kind of substitutes I can be using for the things I was doing before, and found that wine was something I really enjoyed and so I probably had a couple of glasses every day with dinner and stuff. Before, with parties and things and going out a lot more, it was beer and hard liquor were much more common, but now it’s a lot less. Before, wine was more like for a personal moment or something that’s only saved for special occasions and beer or liquor would be a lot more common, but I think that transition from those two types of alcohol to more so wine during dinner. | 1011, male |

| Theme 3: A main contributor to changes in drinking behavior is a decrease in in‐person social interaction and different contexts of drinking. | |

| I like to drink when I go out dancing and so that’s definitely changed. I also think much more of my drinking at home is more like casual – I’m like making dinner and I have some wine or I’m doing homework and I have a cider. Or the other circumstance would be like being on Facetime with friends and having like a Zoom party, but I’m not…it’s much calmer and that changes. Also like the desire to be intoxicated is less. There still like is that element but because I’m alone, it’s changed. | 1017, female |

| Now with COVID‐19, it’s sort of been similar that I drink on the weekends, but it’s a different kind of drinking because it’s with a couple of friends rather than a large group or an actual party, so it’s more relaxed. I have maybe 2 people over on the weekends now…It’s less as well definitely. Even if the time spans the same, I still have fewer drinks. | 1007, male |

| As a first‐year at college, I would say the large majority of my drinking is social drinking. With that limited social activity, that’s not happening. That’s been the limiting agent in my drinking behavior. If I do drink [now] it’s with a meal. Then it’s 1‐2 beverages, which is not what it would be at school. | 1009, male |

| I would say I drink a lot more at [school] just because I’m surrounded by people, like a social event where I would (a) drink more and (b) drink more heavily | 1016, female |

| Theme 4: Another contributor to changes in drinking behavior is a change in living situation, particularly a move off campus and home with parents | |

| I’m not comfortable drinking around my mom at least not anything past a single glass of wine so that’s definitely changed it. | 1017, female |

| I would also drink less because there’s no big incentive to drinking at home. It’s also harder to get alcohol at home. | 1002, female |

| I have relocated from my off‐campus apartment to my parents’ house. Only one person in my family drinks alcohol at all, so there’s really not a lot of it in the house and I didn’t bring any with me… [at school] I have alcohol on hand, I have a large bottle of vodka on hand I can pour from whenever I feel like it. But here, unless I go out and buy beer for instance, there just won’t be any…Additionally, since only one person in the house drinks there is sort of a reverse social pressure. Moralizing aside, you don’t want to be the only drunk person. And the one person in the house who drinks is very moderate, only one or two drinks with dinner. I would say my pattern has also shifted to more or less exclusively one or two beers with dinner. | 1006, non‐binary female |

| [My parents] are fine with drinking, but obviously like they wouldn’t want me to be like super, super drunk, but they’re OK with me having a couple drinks. I still see my girlfriend, and like on weekends we’ll maybe have some wine or some mixed drinks or something but it’s usually not very much since we have to be at one of our houses, even if our parents are asleep, they could wake up so we can’t get like blasted. | 1012, male |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Study 1 Results

Descriptives

Across 28 daily surveys prior to interviews, we observed 169 drinking events (34% of days assessed). Participants consumed an average of 2.33 (SD = 0.81) drinks per drinking day. In contrast, at baseline (1 week after campus closed, when participants reported typical past‐month drinking), they reported typical consumption of 5.08 (SD = 1.03) drinks per day. Most participants (n = 13, 72%) had moved back home with parents upon campus closing due to COVID‐19, 3 remained in off‐campus housing, and 2 moved in with someone other than parents.

Qualitative Themes

Four primary themes emerged (Table 2). First, students’ drinking frequency increased, while quantity decreased. There was consensus among participants that the number of drinking days per week had increased following COVID‐related closure. However, they indicated heavy drinking was much more typical when back at school, with friends; and accordingly, they were less likely to get intoxicated since leaving campus. Several participants described a pattern of consuming a single drink with dinner, which was not characteristic of their preclosure drinking behavior. Theme 2 suggested the type of alcohol consumed changed from hard liquor to wine and/or beer. While reasons for this change were not thoroughly revealed, some alluded to drinking with family during meals, where they consumed what was offered and/or available.

The remaining 2 themes help to understand why drinking changed. Theme 3 suggested a main contributor to changes in drinking behavior was a decrease in in‐person social interaction and changes in drinking contexts. Instead of large parties, participants described drinking in small gatherings, via online meetings with friends, or with family. Theme 4 indicated another contributor was a change in living situation, particularly a move off campus to home with parents. Some described it was less acceptable to drink heavily around parents, or there was less of a desire to drink to intoxication at home.

Study 2 Materials and Methods

Participants

The Study 2 sample was taken from a larger study on simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use among college students enrolled in fall 2017 (White et al., 2019). The larger study included full‐time students from 3 state universities (2 in Northeastern United States and 1 in the Northwest), age 18 to 24 years, who reported past‐year alcohol and cannabis use. Schools A and C are located in an urban environment and School B in a suburban environment; the percent of undergraduates who were full‐time ranged from 83% to 88% across the schools, with 37.5% White at School A, 44.1% at School C, and 76.5% at School B.

Procedures

Freshmen or sophomores in the larger study who indicated willingness to be contacted for future studies were eligible to participate in the present study. On May 25, 2020, participants were sent email and text invitations to participate in an online survey about the impact of COVID‐19. The last survey was completed on June 9, 2020. For the 3 main universities included, campuses closed between March 9 and March 16, 2020. A total of 473 students were invited. Of these, 312 (66% of those invited; 71% of 439 with valid email addresses) responded. Analyses comparing these 312 to the 161 who did not respond revealed no significant differences in demographic characteristics or past 3‐month alcohol or cannabis use frequency collected at baseline in the larger study. The majority of the sample were still enrolled at the same school as at baseline (80.1%); 10.3% were enrolled at another school; 9.6% were no longer in school.

Measures

Alcohol use

Participants completed the DDQ (Collins et al., 1985) with reference to “a typical week before your campus was closed” (referred to here as preclosure) and “a typical week since your campus was closed” (postclosure). From this, we created 4 summary measures of pre‐ and postclosure drinking: total number of days drinking, total number of drinks per week, maximum number of drinks in any 1 day that week, and average number of drinks per drinking day. Frequency of getting drunk was a single item (never [1] to every time [5]). Type of alcohol consumed included beer, liquor (mixed drinks, shots), and wine or champagne (check all that apply), coded 1 for yes and 0 for no for each type consumed. Preclosure HED status was calculated from DDQ data. Participants who reported 1 or more HED day (4+/5+ drinks per occasion for females/males) were coded as HED; those with zero were coded as non‐HED. This latter group included those who did not report drinking preclosure (n = 18).

Context

Social context was assessed using the item “When you use/used alcohol, who do/did you drink with?” with the following response options (check all that apply): Nobody/alone; Romantic partner; Roommate/Housemate; Friend/Acquaintance; Parent/Caregiver; Sibling; Other Family member; Stranger. Participants also indicated the degree to which they drink with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) currently vs. before campus closed on a 5‐point scale (Much Less to Much More Frequently), with options for never drink with parent(s) and not applicable (do not have parent/caregiver).

Location context was assessed using the item “When you use/used alcohol, where do/did you drink?” with the following response options (check all that apply): your house/dorm/residence hall; someone else's house; party; bar, nightclub, pub, or restaurant; outdoors (park, beach, etc.).

Reasons for Change in Drinking

Participants were asked whether their drinking frequency and quantity had decreased, remained the same, or increased since campus closure. Among participants who reported a postclosure decrease in frequency (n = 125) or quantity (n = 148), and participants who reported a postclosure increase in frequency (n = 118) or quantity (n = 80), we probed reasons for the decrease or increase (check all that apply). We examined reasons for frequency separately from quantity to capture specificity (e.g., “do not want to drink” vs. “do not want to be drunk”). Given the lack of standard measures of reasons for changing drinking behavior and the unique circumstances COVID‐19 presented, a checklist of reasons was developed by the authors based on constructs in the drinking motives literature (Cooper et al. 2016), research on limiting or abstaining from drinking (Epler et al., 2009), and COVID‐related work by Acuff and colleagues (2020). Reasons fell into 6 broad categories (context, access/opportunity, coping with distress, upbringing, self‐control, and risk of harm); see Tables 5 and 6 for a full listing.

Table 5.

Reasons for Decreases in Alcohol Consumption in Study 2

| Reason | Decrease in Frequency (n = 125) | Decrease in Quantity (n = 148) |

|---|---|---|

| Context a | 88.8% | 83.8% |

| Reduced social opportunities b | 88.8% | 80.4% |

| Heavy drinking is not part of the culture where I am currently living | – f | 23.6% |

| Access/opportunity a | 36.0% | 29.7% |

| I have limited access to alcohol | 23.2% | 19.6% |

| I don't have the time | 11.2% | 8.1% |

| Financial reasons | 7.2% | 8.1% |

| Upbringing a | 21.6% | 38.5% |

| Rules at home prohibit/limit drinking c | 14.4% | 16.2% |

| Don’t want to drink in front of parents d | 9.6% | 33.8% |

| I have to hide my drinking | 9.6% | 8.1% |

| Don’t want to drink in front of siblings e | 8.8% | 14.9% |

| Self‐control a | 41.6% | 38.5% |

| I'm trying to be more disciplined about what I consume | 26.4% | 23.0% |

| I have decided to use this opportunity to drink less | 22.4% | 18.2% |

| It makes me feel out of control and there is already too much in my life that I cannot control now | 5.6% | 6.1% |

| I am drinking more frequently, so trying to drink less when I do drink | – f | 6.1% |

| Risk of harm a | 40.0% | 34.5% |

| I'm trying to stay as healthy as possible | 38.4% | 33.8% |

| Alcohol interferes with my sleep | 4.8% | 4.0% |

Domain percentages equal percentage of all participants who endorsed any reason within that domain.

Frequency: “Drinking is a social activity for me and there have been few social opportunities”; Quantity: “It feels odd to drink a lot at home/outside of a social situation

Frequency: “I am not allowed to drink at home”; Quantity: “Rules at home prohibit/limit drinking”

Frequency: “My parents/caregivers are not aware that I drink”; Quantity: “I don't want to be drunk in front of my parents”

Frequency: “I do not want to drink in front of my siblings”; Quantity: “I do not want to be drunk in front of my siblings”

No corresponding item for frequency, given the nature of the item.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Table 6.

Reasons for Increases in Alcohol Consumption in the Study 2 Sample

| Reason | Increase in Frequency (n = 118) | Increase in Quantity (n = 80) |

|---|---|---|

| Context a | 78.8% a | 82.5% |

| It's something fun to do when connecting with friends and/or family virtually | 66.1% | 63.8% |

| The people around me are drinking | 46.6% | 48.8% |

| Heavy drinking is part of the culture where I currently live | – b | 17.5% |

| Access/opportunity a | 98.3% | 93.8% |

| As a result of boredom | 89.0% | 82.5% |

| I have more time to relax and enjoy a drink | 80.0% | 75.0% |

| I don't know what else to do | 33.9% | 36.2% |

| Coping with distress a | 45.8% | 45.0% |

| It helps me deal with stressful situations | 30.5% | 33.8% |

| It helps me get through difficult times | 21.2% | 21.2% |

| It helps me to sleep better | 11.9% | 15.0% |

| I just need it/crave it | 5.1% | 5.0% |

| It makes me feel more in control | 1.7% | 6.2% |

| Risk of harm a | 31.4% | 31.2% |

| The potential consequences of drinking don't feel as severe | 31.4% | 31.2% |

Domain percentages equal percentage of all participants who endorsed any reason within that domain.

No corresponding item for frequency, given the nature of the item.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Analytic Plan

We conducted generalized estimating equations (GEE) (Liang and Zeger, 1986) to examine change in alcohol outcomes and context by including time (preclosure/postclosure) as the predictor. We examined whether pre–post closure‐related changes in drinking varied as a function of HED status by adding an interaction between HED status and time. Count outcomes (e.g., days drinking; total number of drinks) were handled with negative binomial models, and binary (yes/no) outcomes (e.g., consume any liquor; consume any wine; drink with a roommate; drink at home) were modeled with a logit link.4

Study 2 Results

Pre–post Closure Drinking

Change in Consumption

As shown in Table 3 (Column 1, Full Sample), postclosure declines in alcohol consumption were evident for all indices with the exception of days drink/typical week (slight increase). GEE models confirmed all alcohol consumption measures changed significantly from pre‐ to postclosure (see Table S1 for all model estimates). On average, drinking frequency increased (IRR = 1.09), whereas there was a decline in measures of quantity (IRR = 0.86), heaviness (IRR = 0.70 and IRR = 0.75 for maximum drinks and drinks per drinking day, respectively), and drunkenness (IRR = 0.66). Use of liquor specifically significantly decreased from pre‐ to postclosure (OR = 0.27).

Table 3.

Drinking Behavior at Preclosure and Postclosure in Study 2

| Full sample (n = 312) | No HED a (n = 144) | HED (n = 167) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclosure | Postclosure | Preclosure | Postclosure | Preclosure | Postclosure | |

| Days drink/typical week | 2.81 | 3.07* | 2.00 | 2.53** | 3.50 | 3.52 ns |

| # drinks/typical week | 10.95 | 9.44** | 4.03 | 5.42** | 16.91 | 12.95** |

| Max drinks per day/typical week | 4.46 | 3.13*** | 1.85 | 1.92 ns | 6.70 | 4.17*** |

| Average drinks per drinking day/typical week | 3.40 | 2.81*** | 1.57 | 1.47 ns | 4.97 | 2.97*** |

| Frequency drunk b | 3.48 | 2.73*** | 2.89 | 2.41*** | 3.93 | 2.98*** |

| Beer (ref = no) | 73% | 78% ns | 71% | 79% ns | 74% | 77% ns |

| Liquor (ref = no) | 87% | 64%*** | 81% | 67%** | 91% | 62%*** |

| Wine (ref = no) | 64% | 68% ns | 61% | 62% ns | 66% | 72% ns |

Significance of tests for pre–post change is indicated in asterisks: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

ns = not significant.

The No HED group includes nondrinkers as well as non‐HED drinkers. One participant had a missing value for the sex variable and was not assigned a HED status variable because it was computed based on sex.

Frequency of getting drunk while drinking alcohol ranged from never (1) to every time (5).

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Interaction between Change in Drinking Behaviors and HED Status

Each pre–post effect on drinking described above was qualified by a significant interaction between time and HED status (see Table S2), with the greatest effects for drunkenness (IRR = 0.42), quantity (IRR = 0.57), and maximum drinks (IRR = 0.60). Liquor showed significant HED status differences in pre–post closure use (OR = 0.35). Within each HED status group (Table 3, Columns 2 and 3), the only drinking index that decreased significantly from preclosure to postclosure for non‐HED participants was frequency drunk. All indices from the DDQ remained stable (maximum drinks/typical week and drinks per drinking day) or significantly increased (days drink/typical week and number of drinks/typical week). Frequency of being drunk and use of liquor also declined significantly within the non‐HED group. In contrast, all drinking indices except days drink/typical week (which remained stable) significantly decreased for the HED group; unlike the non‐HED group, no drinking behaviors increased.

Pre–post Closure Drinking Context

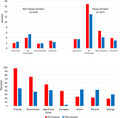

Table 4 shows endorsement of drinking contexts preclosure (Column 1) and postclosure (Column 2) and patterns of change in context: change away from a preclosure context; stable context; change to a new context postclosure (right 3 columns).

Table 4.

Drinking Context Prior to Campus Closing (Preclosure) and Since Campus Closed (Postclosure) in Study 2 (N = 297)

| Preclosure | Postclosure |

% Δ away from context c |

% stable context d |

% Δ to new context e |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social context a | |||||

| Friends | 97.6% | 49.5% | 49% | 51% | 0.7% |

| Roommate | 75.8% | 37.0% | 42% | 55% | 3% |

| Significant Other | 55.6% | 41.1% | 20% | 75% | 5% |

| Stranger | 39.4% | 3.0% | 37% | 63% | 0% |

| Alone | 24.2% | 43.1% | 5% | 71% | 24% |

| Parents | 21.6% | 41.8% | 5% | 69% | 26% |

| Siblings | 18.9% | 30.3% | 7% | 75% | 18% |

| Other family member | 18.2% | 16.5% | 8% | 85% | 7% |

| Total number of contexts |

3.51 (1.61) range: 0 to 8 |

2.68 (1.48) range: 0 to 8 |

Mean change = −0.83 (1.58) range: −6 to 3 |

||

| Location b | |||||

| Others’ home | 87.9% | 33.7% | 57% | 40% | 3% |

| House/home | 86.9% | 83.5% | 12% | 79% | 9% |

| Party | 85.5% | 6.7% | 79% | 21% | 0.3% |

| Bar/restaurant | 79.1% | 5.0% | 75% | 25% | 0.6% |

| Outdoors (park, beach, etc.) | 39.4% | 29.6% | 22% | 66% | 12% |

| Total number of locations |

3.79 (1.14) range: 0 to 5 |

1.58 (1.06) range: 0 to 5 |

Mean change= −2.20 (1.35) range: −5 to 2 |

||

Social context: “When you use alcohol, who did/do you drink with?”

Location: “When you use alcohol, where did/do you drink?”

% Δ away from context corresponds to those that endorsed that context preclosure but not postclosure.

% stable context corresponds to those that endorsed that context preclosure and postclosure.

% Δ to new context corresponds to those that those that endorsed that context postclosure but not preclosure.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Social Context

The most highly endorsed preclosure social context was drinking with a friend/acquaintance, endorsed by nearly all participants. Postclosure, this was reduced by half (49% changed context). Roommates (45%) and strangers (37%) also showed large changes, with many participants no longer drinking in these contexts. In contrast, there was more movement toward drinking alone, with parents, and with siblings. On average, participants reported less variability in social contexts postclosure, going from 3.5 contexts preclosure to 2.7 postclosure.

Of the 195 respondents who drank with a parent/caregiver postclosure, 41.0% reported drinking more frequently with them than before (5.1% much more frequently); 43.1% about the same as before, and 15.8% less frequently than before (9.7% much less frequently).

Location Context

Preclosure, there were high rates of drinking across all contexts, whereas the dominant location for drinking postclosure was house/dorm; this was not a change from preclosure (79% reported this context both pre‐ and postclosure). There were reductions for all other contexts, with the greatest changes being party (79% no longer drinking in that context), bar/restaurant (75% reduction), and others’ home (57% reduction). On average, participants reported less variability in location context postclosure, moving from 3.8 contexts preclosure to 1.6 postclosure.

Reasons for Change

Tables 5 and 6 shows endorsement rates for reasons for decreasing and increasing alcohol use, organized by the 6 broad categories (context, access/opportunity, coping with distress, upbringing, self‐control, and risk of harm). By far, the most prominent perceived reason for a decline in drinking was a change away from a social setting, with “reduced social opportunities/settings” endorsed by 89% (frequency)/80% (quantity). Self‐control reasons for drinking reduction (e.g., trying to be more disciplined about drinking) were also highly endorsed (roughly 40% for declines in both frequency and quantity). Reduced access/opportunity (particularly “limited access to alcohol”) was reported by about one‐third of the sample. Upbringing‐related reasons for decreases in drinking (e.g., house rules limiting alcohol use) were more strongly endorsed for quantity (38%) than frequency (22%). Risk of harm was also indicated by a large number of participants, especially with respect to trying to maintain health (38%/34%).

Increased opportunity was a reason endorsed by virtually all participants who reported increases in alcohol intake, with boredom (89%/82%) and leisure time (80%/75%) highly endorsed. Social context again featured prominently as a reason for COVID‐related drinking increases, including seeking virtual social interactions with friends and family (66%/64%) and social environment favoring alcohol use (47%/49%). About one‐third of the increasers reported increased drinking due to stressful situations, and one‐third perceived reduced consequences of postclosure drinking.

Discussion

A mix of qualitative and quantitative methods was used to obtain a well‐rounded understanding of both how and why drinking behavior changed for the college student drinkers studied here as a result of a dramatic change in life circumstances (e.g., required campus departures) due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Results from 2 studies with unique samples and unique approaches to data collection and analysis were complementary and revealed several key findings. There was convergent evidence of downward changes in drinking quantities attributable to changes in social contexts and drinking locations. Reductions in drinking also reflected reduced access, family disapproval of or rules against drinking, desire for self‐control, and risk of harm. At the same time, increases in drinking were attributed to boredom, increased time, and both social and coping motives for use. Each of the key findings, and their implications, is discussed below.

Changes in Drinking Behavior

In Study 1, which included qualitative interviews with heavy‐drinking students from a private, 4‐year, urban university, participants consistently reported that following COVID‐19‐related campus departures, they drank more often, but less per occasion. An important caveat to these findings are that qualitative data on change in drinking due to COVID‐related factors were collected following exposure to a brief intervention involving daily self‐monitoring and personalized feedback. While participants attributed changes in their drinking to new living situations and fewer social opportunities, a plausible alternative explanation is that change was due to participation in this intervention pilot, and misattributed to these other factors.

Nonetheless, these qualitative data were corroborated, to an extent, by the survey data in Study 2. Specifically, when collapsing across the entire sample of heavy and nonheavy drinkers, drinking frequency increased, while all measures of quantity as well as frequency of drunkenness decreased.

Interaction tests in Study 2 revealed that changes differed for HED vs. non‐HED drinkers, with changes in frequency outcomes pronounced for the non‐HED drinkers. Specifically, those who did not report HED preclosure showed significant increases in drinking frequency, but decreases in frequency of intoxication. Findings for non‐HED drinkers were more nuanced for quantity; some indicators remained stable (maximum drinks, drinks per drinking day), while drinks per week increased. This pattern of results suggests that the increase in drinks per week for non‐HED drinkers was a function of more drinking days, rather than more drinks on any given occasion. In contrast, while the majority of drinking indices significantly decreased for those who reported HED preclosure, drinking frequency remained stable. This is at odds with what the heavy drinkers in the qualitative sample described, which may be due to either the different measurement approaches (a general reflection on change in the qualitative interviews vs. completion of 2 weekly grids assessing pre–post drinking), differences between the universities from which these students were drawn, or other characteristics of the samples. It is also inconsistent with studies with adult samples showing heavier drinkers were more likely to report increases in pandemic‐specific drinking than non‐HED drinkers (Holmes, 2020; Weerakoon et al., 2020). Taking the findings from both our samples together, results suggest that on the one hand, COVID‐19 departures from campus may have been protective for heavier drinkers, resulting in drinking behavior that is less risky. On the other hand, while non‐HED drinkers reported a lower frequency of being drunk, they consumed more total drinks per week (due to more days drinking) than they did preclosure.

Increases in both quantity and frequency following the announcement of campus closing were also observed in a lighter drinking college student sample (Lechner et al., 2020). There was a substantial reduction in number of drinks in the week after compared to the week preceding lockdown in a heavier drinking college sample (Bollen et al., 2021), although it is difficult to disentangle frequency and quantity in a measure of units per week. Notably, while the upward changes in drinking for light drinkers and downward changes for heavy drinkers may suggest “regression to the mean,” the heavier drinkers still drank more heavily than the non‐HED drinkers postclosure. Nonetheless, the increases for lighter drinkers in the Lechner and colleagues (2020) study as well as Study 2 could have important implications; it is possible that these previously light drinkers may establish new and potentially problematic drinking patterns that carry forward as they progress through young adulthood.

Findings from both studies also suggested a decrease in consumption of liquor. This change was most notable among the HED drinkers in Study 2, where liquor consumption decreased from 91% to 62%. There was evidence in Study 1 that beer and wine were more commonly consumed postclosure; however, a statistically significant difference was not observed in Study 2. The consistently observed decrease in liquor consumption is likely a function of changes in students’ drinking contexts. For example, students previously living on campus may have found liquor easier to conceal to avoid sanctions from their university. It may have also served as a cheap way to reach intoxication quickly, often characteristic of “pregaming” (Ogeil et al., 2016), when students were still drinking in their typical social situations. In Study 1, many participants described the shift to drinking with family at dinner, during which time liquor either may not be available/offered, or may not be seen as socially acceptable. It is yet unknown whether the shift away from liquor will maintain once students return to campuses. If so, this may represent a positive change, given risks (e.g., blackouts) associated with rapidly rising blood alcohol concentrations that can occur upon taking “shots” (Labrie et al., 2011; Mochrie et al., 2019; Newman and Abramson, 1942) and as liquor, compared to beer or wine, consumption leads to experiencing more negative consequences (Stevens et al., 2020).

Understanding COVID‐related Changes in Drinking

Reductions in Alcohol Use

On average, both samples of college student drinkers reported a decline in heavy drinking due to COVID‐19. Findings consistently supported concomitant movement away from social drinking contexts. Study 1 qualitative data suggested that a main contributor to reductions in drinking behavior was a decrease in in‐person social interaction and a shift to different drinking locations. Participants noted they were no longer attending large parties and instead drinking in small gatherings, via online interactions with friends, or only with family. Study 2 quantitative findings likewise revealed decreases in the extent to which students were drinking with friends, roommates, and strangers and demonstrated that drinking at parties was far reduced, as was drinking in bars/restaurants and other people’s homes. The present study finding that the most common reason for downward shifts in heavy drinking was reduced social opportunities and/or settings is also consistent with a recent study (Chu et al., 2020) showing that one of the primary reasons for COVID‐related decreases in cannabis use was fewer opportunities for social interaction. It is also consistent with the broader college student literature demonstrating that college students consume more alcohol on days when they spend more time socializing (Finlay et al., 2012). Additionally, students were drinking in both fewer different social contexts and locations; this is important because research supports a prospective association between number of social and physical contexts in which alcohol is consumed and heavy drinking/alcohol problems (Connor et al. 2014; White et al., 2020a,b). Thus, reductions in social contexts are an important contributor to reductions in heavy drinking.

The qualitative data indicated that another contributor to a decline in drinking was a change in living situation, particularly a move home with parents. Some described that it was less acceptable to drink heavily around parents, or that there was less of a desire to drink to intoxication at home, suggesting that this move may explain changes in frequency of drunkenness in particular. Our findings are consistent with a study of mandated college students for whom reduced drinking during the summer months was explained by living with parents during that time (Miller et al., 2016) and expand upon a recent study using the same data as Study 2 that indicated that a move away from living with peers to parents was associated with greater decreases in quantity and frequency relative to those who remained living with parents or peers (White et al., 2020a,b), also highlighting the importance of physical context. As noted in Epler and colleagues (2009), as college students individuate from their families, they are less likely to maintain strong convictions about the unacceptability of drinking alcohol; it stands to reason that when students return home, they are again faced with these proscriptions or norms against heavy drinking.

Although 92% of participants in Study 2 reported it was easy to obtain alcohol during the pandemic, some reported reductions in drinking due to limited access to alcohol, which also may be a function of their changed living situation. Participants may be able to secure (any) alcohol but not at quantities desired. Chu and colleagues (2020) also showed that a primary reason for decreasing cannabis use was decreased availability. Participants also strongly endorsed reducing both quantity and frequency of drinking to remain healthy, although it is not clear whether this was specific to COVID‐19‐related health concerns or simply a time where participants sought to make positive life changes. This is consistent with work indicating that college students desiring to abstain from drinking or limit the amount of alcohol consumed do so in part to minimize risk of harm (Epler et al., 2009). Some participants noted a desire to be more disciplined, which also parallels self‐control reasons for limiting or abstaining drinking among college students. In line with our findings, 1 recent study conducted in the UK also found that attempts to cut down on drinking increased among some high‐risk drinkers during lockdown (Jackson et al., 2020).

Increases in Alcohol Use

Although, on average, declines in drinking were observed, particularly among the heavier drinkers and for measures of drinking quantity, some participants reported drinking either more frequently or larger quantities. Some of these increases reflected social contexts that are likely unique to the pandemic; for example, “virtual” social drinking (e.g., Zoom happy hours) was cited as 1 reason for increased use. Although a change in social context was frequently cited as a reason for drinking reductions, there was still a sizable portion of the Study 2 sample that indicated drinking more frequently (although not necessarily more heavily) with their parents than before. The increase in drinking with parents and siblings in both samples is noteworthy, with important implications. Siblings may have served as drinking companions in the absence of one’s typical friends (Maggs, 2020). The nature of the pandemic also may have resulted in shifts in parent drinking as well (e.g., due to stress or changes in routine; Rodriguez et al., 2020) and/or parental permissiveness of drinking (e.g., granting exceptions to typical rules). Even if alcohol use is moderate and relatively benign in home situations, parental provision of alcohol, modeling of frequent drinking, and perceived approval of drinking could have lasting effects on students’ drinking behaviors upon returning to school, given known impacts of parental permissiveness on college student drinking (Mallett et al., 2019; Varvil‐Weld et al., 2012).

More frequent solitary drinking was reported by Study 2 participants. It is possible that a shift toward drinking alone may be one that is simply practical, due to quarantine guidelines. It might also reflect situations where the individual was engaging in drinking using a virtual platform, although Dumas and colleagues (2020) showed in a sample of adolescents that using substances alone was more frequently endorsed than using with friends in a virtual context. Establishing a solitary drinking pattern during the pandemic could be particularly concerning down the road, given the impacts of drinking alone on problematic drinking (Skrzynski and Creswell, 2020). Although other work suggests that motives to drink to reduce distress are associated with increased postclosure drinking in college students (Bollen et al., 2021), only about one‐third of the Study 2 sample who increased their drinking indicated drinking more to deal with stressful situations or get through difficult times. This fits with our understanding of college student drinkers, who are more frequently motivated by positive than negative affect (Howard et al., 2015) and tend more to endorse social and enhancement than coping motives (Kuntsche et al., 2006).

Increased opportunity to drink alcohol was a clear trigger of increased drinking frequency and quantity. Our findings are consistent with research demonstrating links of boredom (Biolcati et al., 2016) and lack of alternate reinforcers (Acuff et al., 2019) with alcohol consumption in youth, as articulated in a recent review of substance use during COVID‐19 (Acuff et al., 2020). Aside from campus departure, a major change in students’ lives due to COVID‐19 has been restrictions on typical activities that occupy time (e.g., sports, travel) that may serve as alternate reinforcers to drinking (Daly and Robinson, 2020). We also replicate findings by Chu et al (2020) that more time, boredom, and fewer responsibilities were among top reasons for increasing cannabis use. Along with fewer responsibilities is the perception that there is lower risk of harm (in the form of reduced consequences) during this time, which was endorsed by about one‐third of those who increased. It will be essential for college student drinkers to find productive ways to occupy the extra free time they may have, given that, as of January 2021, the United States is still dealing with the pandemic and associated social distancing guidelines. In recent months, young adult adherence to COVID‐19 public health measures, including social distancing, has been low (Suffoletto et al., 2020). Anecdotal reports suggest that informal social contacts are responsible for much of the recent disease transmission; whether these increased social interactions (perhaps due to quarantine fatigue) also are also associated with increased rates of drinking needs to be investigated.

Limitations and Conclusions

Despite strengths associated with the use of mixed methods to gain an understanding of COVID‐19 related changes in drinking from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives, there were several limitations. First, both studies relied on recall of behavior prior to COVID‐19 and only provide snapshots in time of the first few months of the pandemic in the United States not allowing a full picture of how things may have continued to progress (or will progress). Second, the qualitative study was conducted with participants who had recently interacted with a personalized feedback intervention for alcohol use. The manner in which this intervention (vs. COVID‐19 and related changes) impacted students’ drinking behavior is unclear, as the collection of outcome data was not a goal of the pilot. Nonetheless, participants enrolled in the intervention pilot were informed that the goal of their participation was simply to provide feedback on the prototype version of the mobile platform at follow‐up, and not to change their behavior. Further, during their interviews (all conducted within 4 days of completing their 28‐day pilot), participants explicitly attributed behavioral changes to COVID‐19 and not to the intervention.

The Study 1 sample was small, yet not uncharacteristic of those seen in qualitative work (Vasileiou et al., 2018). Moreover, the redundancy in data across these 18 participants suggested that we likely reached saturation (Morse, 1995; Morse, 2015) for the themes described here. As evidence, there were multiple illustrative quotes for each quote (beyond those included in Table 2), and coders ensured that final themes adequately characterized the entire data set (rather than just a few individuals). As such, additional interviews would be unlikely to reveal much new information regarding the themes included here. Nonetheless, we did not reach saturation with respect to whether any specific motives for drinking had changed from pre‐ to postclosure, despite asking participants a question about this. A larger qualitative sample may have been necessary to answer this particular research question more rigorously.

Additionally, our findings do not generalize to college students with characteristics that differ from those studied here. Study 1 participants came from a single, private university, and were required to be heavy drinkers. Study 2 participants represented 3 universities, but were required to report past‐year alcohol and cannabis use at baseline. Further, although the Study 2 sample contained a small portion (10%) of noncollege students, our findings are not generalizable to noncollege young adults. In addition, as reported in White and colleagues (2020a,b), the majority of the Study 2 sample (86%) did not live with their parents prior to campus closure, which is slightly higher than the national average (78%) (American College Health Association, 2020); this may be due to the sample being predominately upper‐classmen. Further, many students had the means to return to the parental home on short notice. Context‐related reasons for change also may not generalize to students in other countries.

Despite these limitations, this paper offers a novel and rigorous examination of COVID‐19‐related alcohol use–related changes in college student drinkers that goes beyond (albeit well‐informed) speculation (Clay and Parker, 2020; Marsden et al., 2020). It is critical for researchers, administrators, and parents that pandemic‐related changes in college student drinking patterns and contexts are not only documented but that the reasons behind such changes are well understood.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1. Changes in perceived drinking behaviors pre‐ vs. post‐closure in Study 2.

Table S2. Heavy episodic drinking status as a moderator of drinking behavior changes over time in Study 2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA040880, MPIs: Jackson and White; T32 DA016184, PI: Rohsenow).

Footnotes

Included nauseated/vomited, rude/obnoxious, neglect school‐related obligations, hurt or injured yourself by accident, behaved aggressively, embarrassed yourself, forgot what you did, hangover, drunk driving, regretted romantic/sexual experience.

Students received an email from the campus president on March 12, 2020, indicating that classes would be canceled starting March 16 and to vacate on‐campus or university‐owned properties as soon as possible (by March 22), to complete their semester from home or an alternative location away from campus beginning March 30.

Text messages were sent to participants’ mobile phones twice daily with a link to the online survey assessing prior day alcohol use, engagement in high‐risk behaviors (e.g., pregaming), use of protective behavioral strategies, and negative alcohol consequences. If prior day drinking was endorsed, personalized feedback reports were presented via mobile phone. Feedback reports began with a summary of drinks consumed relative to one’s drinking goal established at baseline. Next, participants chose 1 topic for further feedback: (1) blood alcohol concentration (BAC; calculation of estimated BAC from the prior night, information on factors that influence BAC, effects corresponding to estimated BAC in the typical drinker); (2) high‐risk behaviors (e.g., information on the risk of pregaming); (3) personalized normative feedback (comparison of last night’s drinking to peer norms); (4) consequences (contrasting those reported the night before with consequences the participant indicated at baseline they would like to avoid); and (5) protective behavioral strategies (used, suggested for future use). Participants were compensated based on weekly compliance with surveys.

Results of supplemental analyses that included age as a covariate were virtually identical to the original models; thus, age was not included as a covariate for parsimony.

References

- Acuff SF, Dennhardt AA, Murphy CCJ, Murphy JG (2019) Measurement of substance‐free reinforcement in addiction: a systematic review. Clin Psych Review 70:79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Tucker JA, Murphy JG (2020) Behavioral economics of substance use: understanding and reducing harmful use during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 10.1037/pha0000431. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association (2020) American College Health Association‐National College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2019. American College Health Association, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Avery AR, Tsang S, Seto EYW, Duncan GE (2020) Stress, anxiety, and change in alcohol use during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Findings among adult twin pairs. Front Psychiatry 11:571084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS (2002) Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. J Stud Alcohol 1986:40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE, Wish ED (2008) Social context of drinking and alcohol problems among college students. Am J Health Behav 32:420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Arria AM (2013) Social contexts of drinking and subsequent alcohol use disorder among college students. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 39:38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati R, Passini S, Mancini G (2016) “I cannot stand the boredom”. Binge drinking expectancies in adolescence. Addict Behav Reports 3:70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen Z, Pabst A, Creupelandt C, Fontesse S, Lannoy S, Pinon N, Maurage P (2021) Prior drinking motives predict alcohol consumption during the COVID‐19 lockdown: a cross‐sectional online survey among Belgian college students. Addict Behav 115:106772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Callinan S, Smit K, Mojica‐Perez Y, D'Aquino S, Moore D, Kuntsche E (2020) Shifts in alcohol consumption during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Early indications from Australia. Addiction. 10.1111/add.15275. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu L‐H, Wallace EC, Jaffe AE, Ramirez JJ (2020) Changes in late adolescent marijuana use during the covid‐19 outbreak vary as a function of typical use [Poster presentation]. Research Society on Marijuana 4th Annual Meeting, Virtual due to COVID.

- Clay JM, Parker MO (2020) Alcohol use and misuse during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a potential public health crisis? Lancet Public Heal 5:e259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA (1985) Social determinants of alcohol consumption. The effects of social interaction and model status on the self‐administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol 53:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J, Cousins K, Samaranayaka A, Kypri K (2014) Situational and contextual factors that increase the risk of harm when students drink: Case‐control and case‐crossover investigation. Drug Alcohol Rev 33:401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S (2016) Motivational Models of Substance Use: A Review of Theory and Research on Motives for Using Alcohol, Marijuana, and Tobacco, The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders, Vol. 1, pp 375–420.Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Robinson E (2020) Problem drinking before and during the COVID‐19 crisis in US and UK adults: Evidence from two population‐based longitudinal studies. medRxiv 2020.06.25.20139022.

- The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2020) Drinking alone: COVID‐19, lockdown, and alcohol‐related harm. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 5:625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM (2020) What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID‐19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic‐related predictors. J Adolesc Heal 67:354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer T, Mepham K, Stadtfeld C (2020) Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID‐19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One 15: e0236337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epler AJ, Sher KJ, Piasecki TM (2009) Reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking: a developmental perspective. Psychol Addict Behav 23:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, Ram N, Maggs JL, Caldwell LL (2012) Leisure activities, the social weekend, and alcohol use: evidence from a daily study of first‐year college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73:250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritsenko V, Skugarevsky O, Konstantinov V, Gritsenko V, Skugarevsky O, Konstantinov V, Khamenka N, Marinova T, Reznik A, Isralowitz R (2020) COVID 19 fear, stress, anxiety, and substance use among Russian and Belarusian university students [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 21]. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020: 1–7. 10.1007/s11469-020-00330-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE (2011) Applied Thematic Analysis. CA, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes L (2020) Drinking During Lockdown: Headline Findings. Available at: https://alcoholchange.org.uk/blog/2020/covid19‐drinking‐during‐lockdown‐headline‐findings Accessed August 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Patrick ME, Maggs JL (2015) College student affect and heavy drinking: Variable associations across days, semesters, and people. Psych Addict Behav 29:430–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Garnett C, Shahab L, Oldham M, Brown J. (2020) Association of the Covid‐19 lockdown with smoking, drinking, and attempts to quit in England: an analysis of 2019‐2020 data. medRxiv 2020.05.25.20112656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center (2021) COVID‐19 Data in Motion: Monday, January 4, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/Downloaded January 4, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O’Connor RM, Sherry SB, Stewart SH (2015) Context counts: Solitary drinking explains the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol‐related problems in undergraduates. Addict Behav 42:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R (2006) Who drinks and why? A review of socio‐demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav 31:1844–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Maclennan B, Langley JD (2007) Intoxication by drinking location: a web‐based diary study in a New Zealand university community. Addict Behav 32:2586–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie JW, Hummer J, Kenney S, Lac A, Pedersen E (2011) Identifying factors that increase the likelihood for alcohol‐induced blackouts in the prepartying context. Subst Use Misuse 46:992–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau‐Barraco C, Linden AN (2014) Drinking buddies: Who are they and when do they matter? Addict Res Theory 22:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner WV, Laurene KR, Patel S, Anderson M, Grega C, Kenne DR (2020) Changes in alcohol use as a function of psychological distress and social support following COVID‐19 related University closings. Addictive Behaviors 110:106527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL (1986) Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lipperman‐Kreda S, Mair CF, Bersamin M, Gruenewald PJ, Grube JW (2015) Who drinks where: youth selection of drinking contexts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:716–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL (2020) Adolescent life in the early days of the pandemic: less and more substance use. J Adolesc Heal 67:307–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Reavy R, Russell M, Cleveland MJ, Hultgren B, Larimer ME, Geisner IM, Hospital M (2019) An examination of parental permissiveness of alcohol use and monitoring, and their association with emerging adult drinking outcomes across college. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42:758–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden J, Darke S, Hall W, Hickman M, Holmes J, Humphreys K, Neale J, Tucker J, West R (2020) Mitigating and learning from the impact of COVID‐19 infection on addictive disorders. Addiction 115:1007–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Fogle S, Boyle HK, Barnett NP, Carey KB (2021) Piloting the Alcohol Feedback, Reflection, and Morning Evaluation (A‐FRAME) Program: A Smartphone‐delivered Alcohol Intervention. 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/71041

- Miller MB, Merrill JE, Yurasek AM, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B (2016) Summer versus school‐year alcohol use among mandated college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 77:51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochrie KD, Ellis JE, Whited MC (2019) Does it matter what we drink? Beverage type preference predicts specific alcohol‐related negative consequences among college students. Subst Use Misuse 54:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (1995) The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res 5:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2015) Data were saturated …. Qual Health Res 25:587–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman HW, Abramson M (1942) Some factors influencing the intoxicating effect of alcoholic beverages. Q J Stud Alcohol 3:351–370. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz CL, Green M, Benzeval M, Campbell D, Craig P, Demou E, Leyland AH, Pearce A, Thomson RM, Whitley E, Katikireddi SV (2020) Mental health and health behaviours before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown: Longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. medRxiv 2020.06.21.20136820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nielsen (2020) Rebalancing the “COVID ‐19 Effect” on Alcohol Sales. Available at: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2020/rebalancing‐the‐covid‐19‐effect‐on‐alcohol‐sales/ Accessed August 20, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Ogeil RP, Lloyd B, Lam T, Lenton S, Burns L, Aiken A, Gilmore W, Chikritzhs T, Mattick R, Allsop S, Lubman DI (2016) Pre‐drinking behavior of young heavy drinkers. Subst Use Misuse 51:1297–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Kilian C, Ferreira‐Borges C, Jernigan D, Monteiro M, Parry CDH, Sanchez ZM, Manthey J (2020) Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: Implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 39:301–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Watson WK, McCourt A (2006) Social networks and college drinking: Probing processes of social influence and selection. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 32:820–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Litt DM, Stewart SH (2020) Drinking to cope with the pandemic: the unique associations of COVID‐19‐related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict Behav 110:106532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland B, Haesebaert F, Zante E, Benyamina A, Haesebaert J, Franck N (2020) Global changes and factors of increase in caloric/salty food intake, screen use, and substance use during the early COVID‐19 containment phase in the general population in France: survey study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 6:e19630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu P (2020) Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus 12:e7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]