Abstract

Background:

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a severe and life-threatening form of alcohol-associated liver disease. Only a minority of heavy drinkers acquires AH, suggesting a genetic basis for the susceptibility to and severity of AH.

Methods:

A cohort consisting of 211 patients with AH and 176 heavy drinking controls was genotyped for five variants in five candidate genes that previously had been associated with chronic liver diseases: rs738409 in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), rs72613567 in hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13), rs58542926 in transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), rs641738 in membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7 (MBOAT7), and the copy number variant in the haptoglobin (HP) gene. We tested the effects of individual variants and the combined/interacting effects of variants on AH risk and severity.

Results:

We found significant associations between AH risk and the risk alleles of rs738409 (P=0.0081) and HP (P=0.0371), but not rs72613567 (P=0.3132), rs58542926 (P=0.2180), nor rs641738 (P=0.7630), after adjusting for patient’s age and sex. A multiple regression model indicated that PNPLA3 rs738409:G [OR=1.59 (95% CI: 1.15–2.22), P=0.0055] and HP*2 [OR=1.38 (95% CI: 1.04–1.82), P=0.0245] combined and adjusted for age and sex also had a large influence on AH risk among heavy drinkers. In the entire cohort, variants in PNPLA3 and HP were associated with increased total bilirubin and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, two measures of AH severity. The HSD17B13 rs72613567:AA allele was not found to reduce risk of AH in patients carrying the G allele of PNPLA3 rs738409 (P=0.0921).

Conclusion:

The current study demonstrates that PNPLA3 and HP genetic variants increase AH risk and are associated with total bilirubin and MELD score, surrogates of AH severity.

Keywords: Alcoholic liver disease, genetic risk, haptoglobin, HSD17B13, PNPLA3

Introduction

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) has a spectrum of hepatic phenotypes that are the result of acute or chronic alcohol overconsumption (Crabb et al., 2020). Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a severe phenotype of ALD, characterized by liver inflammation, progression to cirrhosis, and a high mortality rate (Gao and Bataller, 2011, Liangpunsakul et al., 2016). A clinical diagnosis of AH is based on a specific alcohol consumption pattern, and aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels, among other criteria (Crabb et al., 2020, Liangpunsakul et al., 2016). Despite similar levels of heavy alcohol consumption, only some individuals develop AH, suggesting a genetic basis for the predisposition to and severity of AH, which thus far is poorly understood (Sozio et al., 2010).

We have previously performed a pilot genome-wide analysis of AH to identify genetic variants associated with AH (Beaudoin et al., 2017). The loss-of-function G allele of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs738409 in the gene encoding for patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) showed an association signal with AH (Liangpunsakul et al., 2016), albeit not at genome-wide significance (Beaudoin et al., 2017). Other studies have demonstrated that the rs738409:G allele is associated with increased mortality due to severe AH (Atkinson et al., 2017), and susceptibility to steatosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Romeo et al., 2008), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (Guichelaar et al., 2013), ALD and clinically evident alcoholic cirrhosis (Tian et al., 2010).

Other genetic variants have been described recently to influence the risk for and severity of liver disease. A recent genome-wide association study revealed that a splice donor variant (rs72613567:dupA) in the gene encoding for the hepatic lipid droplet-associated hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) is associated with chronic liver disease (Abul-Husn et al., 2018). The rs72613567:AA allele was associated with lower levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and decreased risk of ALD in patients of European descent (Abul-Husn et al., 2018). The rs72613567:AA allele was also found to be associated with reduced risk of NASH, alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Abul-Husn et al., 2018, Stickel et al., 2020). Furthermore, the T alleles of transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2) and rs641738 in membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7 (MBOAT7) have been identified as risk loci for alcohol-related cirrhosis, NAFLD, and other (chronic) liver diseases (Buch et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2019, Helsley et al., 2019). However, it is unknown whether these variants modulate the risk and severity of AH.

Finally, since oxidative stress is implicated in the pathogenesis of AH and other ALDs (Zima and Kalousova, 2005, Ambade and Mandrekar, 2012), variants in genes with roles in the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may influence AH. Haptoglobin (HP) is an acute-phase plasma glycoprotein that binds to free hemoglobin, resulting in a reduction of hemoglobin-mediated ROS production (Bertaggia et al., 2014). The two major alleles of the HP gene (*1 and *2) result in different phenotypes, with the *2 allele resulting in inferior antioxidant protection compared to the *1 allele. Genetic variation in the HP gene has been associated with differences in antioxidant activity and certain disease phenotypes, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus (Tseng et al., 2004), and outcome of vitamin E treatment in NASH (Banini et al., 2019). Association of AH risk with HP genetic variation has not previously been studied.

In the current study, the individual roles of genetic variants in PNPLA3, HSD17B13, TM6SF2, MBOAT7 and HP, as well as their combined/interacting effects, are assessed in modulating the risk and markers of AH severity. The analysis provides novel insights into the effects of these five important genetic polymorphisms on AH risk and surrogates of severity.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohort

AH patients (n = 211) and heavy drinking controls (n = 176) were recruited from Indiana University, Mayo Clinic, and Virginia Commonwealth University, and enrolled into the prospective Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment (TREAT) study (NCT02172898; registered at ClinicalTrials.gov). A local institutional review board at each site approved the study protocol. Enrolled subjects provided informed consent, after which demographic information, medical history and blood samples were collected. AH was defined based on previously published clinical, biochemical and histological criteria (Liangpunsakul et al., 2016) and consistent with a recent consensus definition proposed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortium Investigators (Crabb et al., 2016). This definition is based on history of heavy alcohol consumption (defined as >40 g/day on average in women and >60 g/day on average for men for a minimum of 6 months and within the 6 weeks prior to study enrollment), clinical evaluation and appropriate laboratory testing (as defined as total bilirubin >3 mg/dL and AST >50 U/L). When the diagnosis of AH remained in question, a liver biopsy (if clinically feasible and the subject had no contra-indications) was required. Heavy drinking controls were selected based on extensive alcohol consumption (similar to patients with AH) determined by the total number of drinks in the past 30 days [Timeline Followback (TLFB)] and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), while having blood AST and ALT <50 U/L, total bilirubin <1 mg/dL, and platelet count >140,000 cells/mm3. Physical examinations were performed on heavy drinking controls to exclude evidence for substantial ALD (e.g., ascites), but these subjects did not undergo procedures such as abdominal ultrasound or elastography.

Variant Genotyping

DNA samples from the TREAT consortium were used to genotype variants in the HP, PNPLA3 HSD17B13, TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 genes. HP protein is encoded by a polymorphic gene with two main alleles (HP*1 and HP*2). The sequences of HP*1 and HP*2 are similar with the main exception that HP*2 contains a 1.7 kb copy number variant due to a tandem two-exon segment alteration (Langlois and Delanghe, 1996, Boettger et al., 2016). The utilized TaqMan assay for HP genotyping is based on sequence-specific differences between the HP*1 and HP*2 alleles. The allelic discrimination assay is a multiplexed (one primer/probe pair per reaction), end-point (data is collected at the end of the PCR process) assay. Allelic discrimination was performed using TaqMan probes (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) as described in Renner, et al with some modifications (Renner et al., 2016). In brief, the FAM fluorescent reporter dye corresponds to a site in HP*2 intron 4, and the VIC fluorescent reporter dye corresponds to identical sites in HP*1 intron 4 and HP*2 intron 6. The genotype of each sample is determined by the fluorescence levels of the reporter dyes, and samples of the same genotype cluster together when plotted. Each reaction contains 5 μL 2X TaqMan Universal PCR Mastermix, No AmpErase UNG, 3.875 μL water, 0.125 μL 80X Assay Mix, and 1 μL sample DNA. Eight controls were included on each 96-well plate: two no-template controls, two replicate heterozygous samples and two replicates of each of the homozygous samples. Because genotyping is determined by endpoint reading, the PCR was carried out in standard Applied Biosystems thermocyclers (AB2720, SimpliAmp and Veriti, ThermoFisher). The PCR products were analyzed in an ABI PRISM® 7300 Sequence Detection System (SDS) instrument (ThermoFisher). SDS Software 1.3.1 was used to convert the raw data to pure dye components and to plot the results of the allelic discrimination on a scatter plot of Allele X versus Allele Y.

Three SNPs including PNPLA3 (rs738409, C>G), an Ile to Met substitution, TM6SF2 (rs58542926, C>T), a Glu to Lys substitution, and MBOAT7/TMC4 (rs641738, C>T), a Glu to Gly substitution, were genotyped using TaqMan probes for allelic discrimination (ThermoFisher). The genotyping protocol is similar as described above and details have been published previously (Hendershot et al., 2009). The rs72613567 SNP in the HSD17B13 gene is an insertion variant (A/AA) near the donor splice site of exon 6, predicted to result in a splice donor variant with altered function. Genotyping was performed using a modified single nucleotide extension reaction, with allele detection by mass spectrometry (Sequenom MassARRAY® System; Sequenom, San Diego, CA) (Xuei et al., 2006, Wetherill et al., 2008, Gabriel et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis

The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables (e.g., sex, allele frequencies, genotype counts) between groups. The generalized linear model was used for comparison of continuous variables (e.g., hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine) between groups. The logistic regression model was employed to evaluate whether multiple genotypes adjusted for each other influence the risk for AH among heavy drinkers. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were calculated to show the association between AH risk and genotypes.

Statistical tests were performed in SAS version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc. (Cary, NC), GraphPad Prism version 8.2.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA), or R: A language and environment for statistical computing version 3.6.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

The characteristics of the cohort consisting of 211 patients with AH and 176 heavy drinking controls are shown in Table 1. Age (AH: 46.3 ± 10.9 years; control: 44.5 ± 12.2 years), body mass index (AH: 29.3 ± 7.7 kg/m2; control: 28.6 ± 6.8 kg/m2), percent males (AH: 59.2%; control: 62.5%), and percent Caucasians (AH: 88.6%; control: 84.1%) were balanced between AH and control groups (P > 0.05). Among Caucasians (reporting one race only), 4 individuals (1.2%) identified as “Hispanic or Latino”. The remaining clinical measures and laboratory tests frequently used for characterization of ALD patients, with the exception of creatinine, were significantly different between the two groups. In patients with AH, 126 (59.7%) had severe AH with Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score >20. Complications of liver disease (ascites, encephalopathy or varices) were present in 99 (78.6%) patients with severe AH. Cirrhosis was histologically confirmed in 8 of 26 patients who underwent liver biopsy.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with alcoholic hepatitis (AH) and heavy drinking controls without hepatitis.

| Variables | AH Cases (n = 211) | Controls (n = 176) | P-value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.3 ± 10.9 | 44.5 ± 12.2 | 0.1088 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 7.7 | 28.6 ± 6.8 | 0.3813 |

| Men, n (%) | 125 (59.2%) | 110 (62.5%) | 0.5134 |

| Race, Caucasian, n (%) | 187 (88.6%) | 148 (84.1%) | 0.1927 |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | 7 (3.3%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.1912 |

| WBC (x103 cells/mm3) | 11.6 ± 7.8 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | <.0001* |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.2 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 2.1 | <.0001* |

| Platelet counts (x103 cells/mm3) | 145.8 ± 84.1 | 238.8 ± 72.7 | <.0001* |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 14.2 ± 11.4 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | <.0001* |

| INR | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | <.0001* |

| AST (U/L) | 137.2 ± 80.7 | 27.8 ± 9.0 | <.0001* |

| ALT (U/L) | 62.0 ± 61.6 | 26.6 ± 11.9 | <.0001* |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 188.9 ± 134.1 | 75.5 ± 30.6 | <.0001* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | <.0001* |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | <.0001* |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.0291 |

| MELD Score | 22.6 ± 7.2 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | <.0001* |

| Total drinks in the past 30 days (TLFB) | 258.7 ± 237.3 | 382.4 ± 286.9 | <.0001* |

| AUDIT score | 24.0 ± 8.7 | 27.7 ± 7.5 | <.0001* |

Asterisks denote statistical significance at α = 0.05 using a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell; INR, international normalized ratio; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; TLFB, Timeline Followback; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Distribution of Allele and Genotype Frequency in AH and Controls

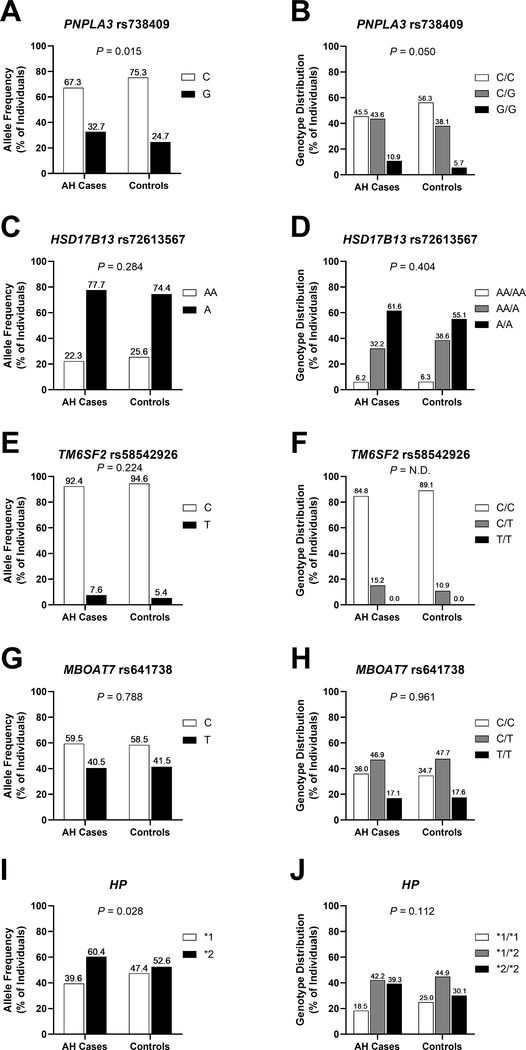

While the allele frequencies of HSD17B13 (rs72613567, P = 0.284), TM6SF2 (rs58542926, P = 0.224) and MBOAT7 (rs641738, P = 0.788) did not show significant relationships with AH among heavy drinkers, the allele frequencies of HP (P = 0.028) and PNPLA3 (rs738409, P = 0.015) did (Figure 1). With respect to genotype counts, neither HSD17B13 (rs72613567, P = 0.404), TM6SF2 (rs58542926, P = N.D.), MBOAT7 (rs641738, P = 0.961) nor HP (P = 0.112) showed a significant association with the case/control status, while PNPLA3 (rs738409, P = 0.050) demonstrated a relationship with AH among heavy drinkers at nominal significance.

Figure 1. Allele frequencies (A, C, E, G, I) and genotype distributions (B, D, F, H, J) of rs738409 (PNPLA3), rs72613567 (HSD17B13), rs58542926 (TM6SF2), rs641738 (MBOAT7) and HP in patients with AH (n = 211) and heavy drinking controls (n = 176).

Chi-squared tests were performed to derive P-values. AH, alcoholic hepatitis; HP, haptoglobin; HSD17B13, hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13; MBOAT7, membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7; N.D., not determined; PNPLA3: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; TM6SF2, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2.

Variants Modifying the Risk of AH

Multivariate logistic regression models after adjusting for patient’s age and sex showed increased risk for AH with the G allele of PNPLA3 rs738409 [OR=1.55 (95% CI: 1.12–2.16), P = 0.0081] and the *2 allele of HP [OR=1.34 (95% CI: 1.02–1.77), P = 0.0371] (Table 2, multivariate models I & V, respectively). No effect on the risk of AH was observed with either the A allele of HSD17B13 rs72613567 [OR=1.18 (95% CI: 0.85–1.65), P = 0.3132], the T allele of TM6SF2 rs58542926 [OR=1.47 (95% CI: 0.80–2.75), P = 0.2180], or the T allele of MBOAT7 rs641738 [OR=0.96 (95% CI: 0.72–1.27), P = 0.7630] as the only independent variable (Table 2, multivariate models II-IV). A multivariate model in which the risk alleles of both PNPLA3 and HP were combined and adjusted for patient’s age and sex revealed slightly larger effects of these two variants on the risk for AH compared to each variant alone [PNPLA3 rs738409 G allele, OR=1.59 (95% CI: 1.15–2.22), P = 0.0055; HP *2 allele, OR=1.38 (95% CI: 1.04–1.82), P = 0.0245] (Table 2, multivariate model VI). All other models in which one of the five loci were combined with another variant and adjusted for patient’s age and sex showed no significant effect of both variants in influencing AH risk among heavy drinkers.

Table 2.

Results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression models of candidate gene variants modulating the risk of alcoholic hepatitis among heavy drinkers.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) a | P-value b |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate Models | ||

| PNPLA3 (rs738409) | 1.48 (1.08–2.05) | 0.0157* |

| HSD17B13 (rs72613567) | 1.19 (0.86–1.66) | 0.2920 |

| TM6SF2 (rs58542926) | 1.48 (0.81–2.75) | 0.2090 |

| MBOAT7 (rs641738) | 0.96 (0.72–1.28) | 0.7900 |

| HP | 1.34 (1.02–1.76) | 0.0378* |

| age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.1099 |

| sex | 0.87 (0.58–1.32) | 0.5139 |

| Multivariate Model I | ||

| PNPLA3 (rs738409) | 1.55 (1.12–2.16) | 0.0081* |

| age | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.0438* |

| sex | 0.85 (0.56–1.29) | 0.4551 |

| Multivariate Model II | ||

| HSD17B13 (rs72613567) | 1.18 (0.85–1.65) | 0.3132 |

| age | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.0989 |

| sex | 0.85 (0.56–1.29) | 0.4500 |

| Multivariate Model III | ||

| TM6SF2 (rs58542926) | 1.47 (0.80–2.75) | 0.2180 |

| age | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.1190 |

| sex | 0.81 (0.54–1.23) | 0.3330 |

| Multivariate Model IV | ||

| MBOAT7 (rs641738) | 0.96 (0.72–1.27) | 0.7630 |

| age | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.0960 |

| sex | 0.84 (0.56–1.27) | 0.4190 |

| Multivariate Model V | ||

| HP | 1.34 (1.02–1.77) | 0.0371* |

| age | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.0855 |

| sex | 0.87 (0.57–1.32) | 0.5045 |

| Multivariate Model VI | ||

| PNPLA3 (rs738409) | 1.59 (1.15–2.22) | 0.0055* |

| HP | 1.38 (1.04–1.82) | 0.0245* |

| age | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.0364* |

| sex | 0.88 (0.58–1.34) | 0.5456 |

| Multivariate Model VII | ||

| PNPLA3 (rs738409) | 1.59 (1.15–2.22) | 0.0148* |

| HSD17B13 (rs72613567) | 1.10 (0.78–1.56) | 0.0864 |

| PNPLA3 x HSD17B13 | - | 0.0921 |

| age | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.0504 |

| sex | 0.86 (0.56–1.31) | 0.4781 |

The Odds Ratios (ORs) and Confidence Intervals (CIs) for PNPLA3, HSD17B13, TM6SF2, MBOAT7, HP and age as predictors of alcoholic hepatitis among heavy drinkers correspond to a one unit increase of rs738409 G, rs72613567 A, rs58542926 T, rs641738 T

2 alleles and one year increase of age, respectively. Sex used females as the reference group.

Asterisks denote statistical significance at α = 0.05. HP, haptoglobin; HSD17B13, hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13; MBOAT7, membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7; PNPLA3, patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; TM6SF2, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2.

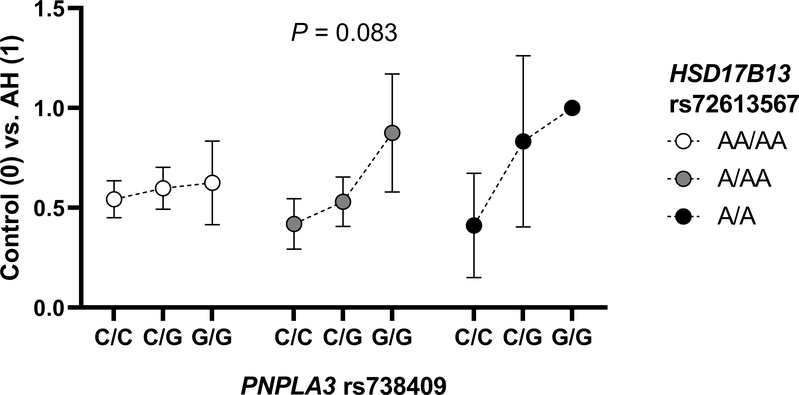

Influence of Interaction of Variants on Risk of AH

Since an interaction between PNPLA3 rs738409 and HSD17B13 rs72613567 was found previously in chronic liver disease (Abul-Husn et al., 2018), the interactive relationship between these two variants was examined in the current study. When evaluating the association between PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and risk of AH among heavy drinkers with each HSD17B13 rs72613567 genotype, no significant effect was noted with the AA allele of HSD17B13 rs72613567 on the risk of AH conferred by the G allele of PNPLA3 rs738409 (P = 0.0921) (Table 2, multivariate model VII; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Relationship between PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype and risk of AH among heavy drinkers with each HSD17B13 rs72613567 genotype.

The y-axis represents the ratio of AH cases to controls for each of the nine PNPLA3 rs738409 and HSD17B13 rs72613567 combined genotypes. The presented P-value corresponds to the interaction term between PNPLA3 rs738409 and HSD17B13 rs72613567 in a logistic regression model (Table 2, multivariate model VII). Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. AH, alcoholic hepatitis; HSD17B13, hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13, PNPLA3: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3.

Variants Modifying Measures of AH Severity and Mortality

Analysis of association of genotype with disease severity [including total bilirubin, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, international normalized ratio (INR), and MELD score showed associations of PNPLA3 rs738409 genotype with total bilirubin, INR and MELD score among AH patients and all subjects (Table 3). Additional trends of genotype-disease severity association were observed for TM6SF2 rs58542926 and HP with ALT, total bilirubin and/or MELD score, among all subjects.

Table 3.

Association of PNPLA3 (rs738409), HSD17B13 (rs72613567), TM6SF2 (rs58542926), MBOAT7 (rs641738), and HP genotypes with disease severity, including total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, international normalized ratio (INR), and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score.

| Genotype | Variables | Cases | Control | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C/C (n = 96) | C/G (n = 92) | G/G (n = 23) | P-value | C/C (n = 99) | C/G (n = 67) | G/G (n = 10) | P-value | C/C (n = 195) | C/G (n = 159) | G/G (n = 33) | P-value | ||

| PNPLA3 (rs738409) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 12.5 ± 10.3 | 14.6 ± 11.5 | 19.3 ± 14.1 | 0.0346 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8400 | 6.4 ± 9.4 | 8.7 ± 11.2 | 13.6 ± 14.6 | 0.0011* |

| AST (U/L) | 146.3 ± 92.5 | 123.7 ± 61.8 | 153.5 ± 89.6 | 0.0928 | 27.1 ± 9.0 | 29.0 ± 8.7 | 26.3 ± 10.6 | 0.3674 | 85.8 ± 88.3 | 83.8 ± 66.5 | 114.9 ± 95.2 | 0.1215 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 66.2 ± 71.3 | 55.7 ± 48.2 | 69.4 ± 65.9 | 0.4220 | 26.2 ± 10.6 | 27.1 ± 13.7 | 26.4 ± 11.5 | 0.8822 | 45.9 ± 54.3 | 43.7 ± 40.2 | 56.4 ± 58.6 | 0.4046 | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 202.7 ± 154.7 | 181.6 ± 123.1 | 160.7 ± 60.6 | 0.3167 | 76.9 ± 34.5 | 74.3 ± 23.8 | 69.9 ± 31.4 | 0.7277 | 138.9 ± 127.7 | 136.8 ± 108.8 | 133.2 ± 67.8 | 0.9619 | |

| INR | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.0454 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.0620 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.0014* | |

| MELD Score | 20.7 ± 6.0 | 23.5 ± 7.1 | 26.9 ± 9.7 | 0.0002* | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 1.1^ | 0.8158 | 13.9 ± 8.1 | 16.8 ± 9.9 | 21.5 ± 11.8 | <.0001* | |

| Genotype | Variables | AA/AA (n = 13) | AA/A (n = 68) | A/A (n = 130) | P-value | AA/AA (n = 11) | AA/A (n = 68) | A/A (n = 97) | P-value | AA/AA (n = 24) | AA/A (n = 136) | A/A (n = 227) | P-value |

| HSD17B13 (rs72613567) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 18.8 ± 13.9 | 13.9 ± 11.3 | 13.8 ± 11.2 | 0.3209 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.1864 | 10.4 ± 13.7 | 7.2 ± 10.4 | 8.2 ± 10.7 | 0.3763 |

| AST (U/L) | 155.3 ± 87.1 | 144.6 ± 77.6 | 131.5 ± 81.7 | 0.3946 | 26.1 ± 8.5 | 27.9 ± 8.5 | 27.9 ± 9.4 | 0.8095 | 96.1 ± 91.2 | 86.3 ± 80.3 | 87.3 ± 80.5 | 0.8597 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 67.7 ± 51.6 | 70.9 ± 75.2 | 56.7 ± 54.0 | 0.2864 | 26.9 ± 9.6 | 27.9 ± 13.4 | 25.6 ± 10.9 | 0.4547 | 49.0 ± 43.1 | 49.4 ± 58.0 | 43.4 ± 44.2 | 0.5038 | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 220.0 ± 122.0 | 187.5 ± 109.1 | 186.6 ± 146.9 | 0.6909 | 77.4 ± 16.9 | 75.3 ± 27.3 | 75.5 ± 34.1 | 0.9784 | 154.6 ± 114.7 | 131.4 ± 97.2 | 139.4 ± 126.1 | 0.6200 | |

| INR | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.1856 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.8249 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.1282 | |

| MELD Score | 23.2 ± 8.1 | 21.5 ± 6.6 | 23.1 ± 7.4 | 0.3515 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 0.2108 | 16.0 ± 10.4 | 14.5 ± 8.8 | 16.5 ± 9.7 | 0.1604 | |

| Genotype | Variables | C/C (n = 178) | C/T (n = 32) | T/T (n = 0) | P-value | C/C (n = 156) | C/T (n = 19) | T/T (n = 0) | P-value | C/C (n = 334) | C/T (n = 51) | T/T (n = 0) | P-value |

| TM6SF2 (rs58542926) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 14.4 ± 11.2 | 12.9 ± 12.7 | N/A | 0.7852 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | N/A | 0.3035 | 8.0 ± 10.7 | 8.3 ± 11.7 | N/A | 0.9741 |

| AST (U/L) | 134.0 ± 82.9 | 156.8 ± 65.1 | N/A | 0.3409 | 27.7 ± 8.7 | 29.6 ± 10.6 | N/A | 0.6824 | 84.3 ± 80.7 | 109.4 ± 80.8 | N/A | 0.1206 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 58.8 ± 57.1 | 79.9 ± 81.9 | N/A | 0.2055 | 26.1 ± 10.4 | 31.2 ± 20.4 | N/A | 0.2062 | 43.5 ± 45.3 | 61.8 ± 69.8 | N/A | 0.0490 | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 190.5 ± 140.6 | 182.3 ± 93.7 | N/A | 0.9520 | 76.3 ± 30.6 | 66.3 ± 26.8 | N/A | 0.4056 | 137.3 ± 119.3 | 139.1 ± 94.4 | N/A | 0.9947 | |

| INR | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | N/A | 0.0803 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | N/A | 0.8308 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | N/A | 0.7806 | |

| MELD Score | 23.1 ± 7.2 | 20.1 ± 6.7 | N/A | 0.0885 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.3 | N/A | 0.8657 | 15.8 ± 9.7 | 15.5 ± 8.2 | N/A | 0.9826 | |

| Genotype | Variables | C/C (n = 76) | C/T (n = 99) | T/T (n = 36) | P-value | C/C (n = 61) | C/T (n = 84) | T/T (n = 31) | P-value | C/C (n = 137) | C/T (n = 183) | T/T (n = 67) | P-value |

| MBOAT7 (rs641738) | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 15.2 ± 11.4 | 13.6 ± 11.0 | 13.6 ± 12.7 | 0.6091 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7665 | 8.7 ± 11.2 | 7.6 ± 10.4 | 7.6 ± 11.4 | 0.6536 |

| AST (U/L) | 134.8 ± 80.7 | 138.8 ± 85.1 | 138.0 ± 69.2 | 0.9474 | 27.7 ± 8.8 | 28.3 ± 9.6 | 26.8 ± 7.7 | 0.7183 | 87.1 ± 80.5 | 88.1 ± 83.6 | 86.6 ± 75.5 | 0.9895 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 66.7 ± 75.4 | 59.2 ± 55.2 | 59.6 ± 44.4 | 0.7055 | 27.4 ± 13.9 | 25.9 ± 10.6 | 26.6 ± 11.3 | 0.7418 | 49.2 ± 60.1 | 43.9 ± 44.3 | 44.3 ± 37.1 | 0.6129 | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 178.1 ± 106.5 | 194.3 ± 156.7 | 197.3 ± 120.0 | 0.6738 | 72.0 ± 22.8 | 81.5 ± 37.1 | 66.0 ± 19.6 | 0.0311 | 130.9 ± 96.3 | 142.5 ± 130.5 | 137.6 ± 110.7 | 0.6748 | |

| INR | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.7920 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9152 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.9311 | |

| MELD Score | 23.7 ± 7.6 | 22.0 ± 6.8 | 21.8 ± 7.4 | 0.2176 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | 7.3 ± 2.0 | 7.3 ± 2.6 | 0.8677 | 16.3 ± 10.2 | 15.4 ± 9.0 | 15.4 ± 9.3 | 0.6449 | |

| Genotype | Variables | *1/*1 (n = 39) | *1/*2 (n = 89) | *2/*2 (n = 83) | P-value | *1/*1 (n = 44) | *1/*2 (n = 79) | *2/*2 (n = 53) | P-value | *1/*1 (n = 83) | *1/*2 (n = 168) | *2/*2 (n = 136) | P-value |

| HP | Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 11.2 ± 9.8 | 14.4 ± 11.2 | 15.3 ± 12.2 | 0.1834 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.1672 | 5.5 ± 8.5 | 7.9 ± 10.7 | 9.5 ± 12.0 | 0.0319 |

| AST (U/L) | 140.9 ± 92.7 | 142.4 ± 85.1 | 129.9 ± 69.5 | 0.5683 | 26.7 ± 8.3 | 28.0 ± 9.5 | 28.4 ± 8.8 | 0.6358 | 80.4 ± 85.5 | 88.6 ± 84.5 | 90.3 ± 73.7 | 0.6591 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 70.9 ± 96.3 | 60.1 ± 43.9 | 59.8 ± 57.4 | 0.6063 | 26.2 ± 15.6 | 26.2 ± 10.4 | 27.3 ± 10.5 | 0.8582 | 47.2 ± 70.2 | 44.2 ± 36.8 | 47.1 ± 48.0 | 0.8410 | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 193.8 ± 116.0 | 195.6 ± 168.7 | 179.6 ± 95.5 | 0.7162 | 73.2 ± 26.1 | 76.8 ± 36.2 | 75.6 ± 25.1 | 0.8277 | 129.9 ± 101.3 | 140.1 ± 138.7 | 139.1 ± 91.5 | 0.7917 | |

| INR | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.2162 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.3706 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.0569 | |

| MELD Score | 20.6 ± 8.9 | 23.0 ± 6.6 | 23.1 ± 6.8 | 0.1742 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 7.6 ± 2.8 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 0.0992 | 13.5 ± 9.3 | 15.9 ± 9.3 | 16.8 ± 9.6 | 0.0393 | |

Bolded text indicates P-values < 0.05; asterisks denote statistical significance at α = 0.05 using a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Two heavy drinking controls were excluded from this particular MELD calculation. Both of these subjects had normal ALT, AST, platelets and bilirubin and no evidence for liver disease by physical examination at enrollment, but evidence of kidney disease (creatinine: 2.3 mg/dL) was found in one subject, and spuriously elevated INR (2.2) in another. HP, haptoglobin; HSD17B13, hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13; MBOAT7, membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7; N/A, not applicable; PNPLA3, patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; TM6SF2, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2.

Among all individuals in our study (n = 387), 52 subjects (13.4%) died within a year of study enrollment, 50 of which were AH patients (i.e., 23.7% of 211 AH patients died within a year of study enrollment). No statistically significant differences in mortality rate between genotypes were observed for the five genetic variants in this cohort (Supporting Table 1). Most of the deaths (66%) in our study occurred in the first 90 days after enrollment. A multivariate analysis for mortality was conducted to evaluate effects of factors, other than the PNPLA3 variant, that may impact mortality at 3 and 12 months, such as MELD, age and sex, and relapse to drinking (Supporting Tables 2 and 3). Our findings remained unchanged: The PNPLA3 variant was still not associated with the 3- or 12-month mortality after adjusting for these factors, but the MELD score was. Relapse to drinking was independently associated with 12-month survival in our study.

Discussion

A genetic basis for AH susceptibility has been hypothesized, with potential roles for a variety of genes and individual variants. Based on associations with other liver diseases, variants in the candidate genes PNPLA3, HSD17B13, TM6SF2, MBOAT7 and HP with adjustment for age and sex were analyzed in the current study as potential modulators of AH risk and measures of severity. Here we show PNPLA3 rs738409:G and HP *2 alleles are associated with increased risk of AH and with increased total bilirubin and MELD score, surrogates of AH severity.

Although the association between PNPLA3 rs738409 and AH risk is not novel, to our knowledge, no prior study found an association between PNPLA3 rs738409 and measures of AH severity. While the role of genetic variants in HSD17B13, TM6SF2, MBOAT7 and/or HP had been studied in other liver diseases including alcoholic cirrhosis and NASH, this study evaluated their effects on risk and surrogates of AH severity. Another novel aspect is that we looked not only at the individual genetic variant effect but also at the combined/interacting effects of these gene variants in modulating AH risk and measures of severity and reported novel effects for the combination of PNPLA3 with HP variants on risk of AH.

We found an association between PNPLA3 rs738409 and AH risk (P = 1.5 × 10−2), but the relationship was not as strong as one might expect based on the observed associations of rs738409 risk allele G with other chronic liver diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (P = 5.9 × 10−10) (Romeo et al., 2008) and clinically evident alcoholic cirrhosis (P = 1.7 × 10−10) (Tian et al., 2010). The relatively small sample size in our study may partially explain this observation. However, the strong association of PNPLA3 genotype with MELD score in AH cases (P = 0.0002) indicates that PNPLA3 is likely a major driver of AH severity. Indeed, a steady and significant increase in MELD score was observed both in AH cases and the cohort as a whole for PNPLA3 genotypes from C/C to C/G to G/G. In line with this observation, a recent meta-analysis indicated that the G allele of PNPLA3 is a risk factor for cirrhosis in patients with ALD (Schwantes-An et al., 2020). Interestingly, in the STOPAH randomized controlled trial of patients with severe AH who received therapy with prednisolone or pentoxifylline with reported short-term improvement in mortality with prednisolone, no association between PNPLA3 genotype and disease severity as gauged by MELD was observed (Atkinson et al., 2017). The PNPLA3 variant was associated with baseline MELD in our study but not in the STOPAH study, probably because of enrollment of patients with severe AH in STOPAH, whereas our study included all comers with AH (mild, moderate or severe). The same study demonstrated, as in our study, a lack of PNPLA3 genotype impact on 90-day survival of AH patients, but showed a significant association of the G/G genotype with an increase in mortality at day 450. In contrast, in our cohort which included severe and non-severe AH patients, we did not find an association between PNPLA3 genotype and mortality during the first 12 months after AH diagnosis even after controlling for relapse to drinking, MELD, age and sex. These discordant findings may be due to differences in populations studied, cohort sizes, and duration of follow up.

HP was also found to be associated with AH risk, despite that HP is not clearly established as a risk factor of chronic liver disease. In addition to an association with outcome of vitamin E treatment in NASH (Banini et al., 2019), relationships between HP genotype and diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease have been identified (Blum et al., 2010). HP protein binds to free hemoglobin, has antioxidant activity, and is primarily produced in the liver, but its specific function in the liver is unclear. Obtaining data on haptoglobin levels, oxidative stress and iron metabolism in the context of AH may be useful in order to elucidate the mechanistic role of HP in increasing risk for AH among heavy drinkers. Our observation in the current study that the combination of PNPLA3 rs738409:G and HP*2 (adjusted for each other) has a larger effect on AH risk compared to only one of the two variants by themselves, particularly when this relationship is further adjusted for age and sex, warrants further investigation. The G allele of the hepatic lipid droplet-associated PNPLA3, which predisposes to hepatic triglyceride accumulation, fibrosis and inflammation, and the *2 allele of HP, which has inferior antioxidant activity, may together exacerbate the risk of AH. If validated in other studies, AH patients with these genetic variant combinations may be observed closer for development of more severe AH. While the effects of HSD17B13, TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 on risk of NAFLD and other liver diseases had been observed in other studies, we did not observe an effect for the studied variants of these genes in our study. The lack of association of these gene variants with AH risk or markers of AH severity may be due to the relatively small size of our cohort.

No significant independent association was found between AH risk and the analyzed HSD17B13 variant, despite the recent observations that HSD17B13 was associated with liver enzyme concentrations, risk of ALD, alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Abul-Husn et al., 2018, Stickel et al., 2020). In addition, Abul-Husn, et al. reported an interaction between HSD17B13 rs72613567 and PNPLA3 rs738409 in association analyses with chronic liver diseases, using a sample size for analysis that was >42,500 subjects (Abul-Husn et al., 2018). Specifically, a protective role for HSD17B13 rs72613567:AA was observed in patients carrying the G allele of PNPLA3 rs738409. While an interaction between HSD17B13 rs72613567 and PNPLA3 rs738409 was evident in the analysis of serum levels of AST and ALT in chronic liver disease (Abul-Husn et al., 2018), in our present analysis of AH patients using a smaller sample size no significant interaction between these two variants was observed.

Given the strength of association between HP and AH noted in the current study, it may be surprising that an association between this variant and other alcohol-associated diseases such as alcohol-related cirrhosis has not been reported in multiple GWA studies and meta-analyses (Buch et al., 2015, Schwantes-An et al., 2020, Innes et al., 2020). In these studies, novel association signals were identified between alcohol-related cirrhosis and variants in TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 (Buch et al., 2015), mitochondrial amidoxime reducing component 1 gene (MARC1) and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U like 1 gene (HNRNPUL1) (Innes et al., 2020), and Fas Associated Factor family member 2 (FAF2) (Schwantes-An et al., 2020), while verifying previously identified variants such as rs738409 in PNPLA3. However, it appears that no association with the HP variant was identified. There are several possible reasons for this discrepant finding: 1) The phenotypes studied are different; acute AH in our study vs alcohol-associated cirrhosis in the GWA studies and meta-analyses reported; 2) While SNPs (e.g., the variants in PNPLA3, TM6SF2, MBOAT7) and short indels (e.g., the insertion variant in HSD17B13) are routinely analyzed in GWA studies, the study of large copy number variants (CNVs; e.g., the studied HP variant is a 1.7 kb CNV) is inherently more complex and troublesome. Although advances have been made in microarray-based CNV genotyping, the reproducibility and validation of CNV calling remain a challenge (Pinto et al., 2011, Haraksingh et al., 2017). The utilization of a customized, multiplexed allelic discrimination assay (Renner et al., 2016) in this candidate gene study was able to find an association signal; 3) Differences in data curation and analysis could also lead to different association findings between studies. For instance, variants may be excluded from the analysis when the missing genotyping rate is above a certain threshold (e.g., >1%), or when the SNP missing rate is associated with case/control status (Beaudoin et al., 2017); 4) The use of multiple different microarrays can result in the possibility that variants such as the HP CNV or surrogate SNPs were included on some microarrays, but not on others (Buch et al., 2015); 5) Phenotypes collected at different times and sites, and in different populations can result in batch effects and more noise. While our association study using candidate gene markers is more limited in scope compared with a GWAS, it has its own advantages, such as the ability to detect an association in a relatively small sample size.

The recruitment of patients that satisfy clinical, biochemical or histological criteria associated with AH, as well as the recruitment of heavy drinking subjects lacking AH is challenging. To date, both of these factors have prevented the recruitment of the substantial numbers of enrolled individuals seen in some human genetic studies. Although the sample size in our analysis is a recognized limitation, studies on AH are scarce, and the current study provides new insights into the genetics underlying AH. Additional, worthwhile opportunities to evaluate genetic risk factors of AH in future, larger studies may include the analysis of genetic variants in the multitude of pathways related to inflammation, a key characteristic of AH.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that PNPLA3 and HP gene variants increase AH risk and are associated with total bilirubin and MELD score, surrogates of AH severity. The impact of these and other genetic variants will need to be investigated in future larger studies in order to advance the understanding of the role of genetic factors in AH development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers 5U01AA021883-04, 5U01AA021891-04, 5U01AA021788-04 and 5U01AA021840-04 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (for the TREAT Consortium) and F31DK120196 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (for JJB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Beaudoin, Dr. Liang, Ms. Tang and Dr. Banini declare no conflicts. Dr. Shah has no conflicts relevant to this work to disclose. Dr. Sanyal: None for this project. Dr. Sanyal is President of Sanyal Biotechnology and has stock options in Genfit, Akarna, Tiziana, Indalo, Durect Inversago and Galmed. He has served as a consultant to Astra Zeneca, Nitto Denko, Conatus, Nimbus, Salix, Tobira, Takeda, Janssen, Gilead, Terns, Birdrock, Merck, Valeant, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Hemoshear, Zafgen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Exhalenz and Genfit. He has been an unpaid consultant to Intercept, Echosens, Immuron, Galectin, Fractyl, Syntlogic, Affimune, Chemomab, Zydus, Nordic Bioscience, Albireo, Prosciento, Surrozen. His institution has received grant support from Gilead, Salix, Tobira, Bristol Myers, Shire, Intercept, Merck, Astra Zeneca, Malinckrodt, Cumberland and Novartis. He receives royalties from Elsevier and UptoDate. Dr. Chalasani had paid consulting activities with following companies in last 12 months: Abbvie, Shire, NuSirt, Afimmune, Axovant, Allergan, Madrigal, Coherus, Siemens, and Genentech. He has received research support from Lilly, Galectin, Gilead, Exact Sciences, and Cumberland. Dr. Gawrieh: Nothing relevant to this work. Consulting: TransMedics, research grant support: Cirius, Galmed, Viking and Zydus.

List of Abbreviations:

- AH

alcoholic hepatitis

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUDIT

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- BMI

body mass index

- HP

haptoglobin

- HSD17B13

hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MBOAT7

membrane bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 7

- MELD

Model for End-stage Liver Disease

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PNPLA3

patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3

- TLFB

Timeline Followback

- TM6SF2

transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2

- TREAT

Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment

- WBC

white blood cell

References

- Abul-Husn NS, Cheng X, Li AH, Xin Y, Schurmann C, Stevis P, Liu Y, Kozlitina J, Stender S, Wood GC, Stepanchick AN, Still MD, McCarthy S, O’Dushlaine C, Packer JS, Balasubramanian S, Gosalia N, Esopi D, Kim SY, Mukherjee S, Lopez AE, Fuller ED, Penn J, Chu X, Luo JZ, Mirshahi UL, Carey DJ, Still CD, Feldman MD, Small A, Damrauer SM, Rader DJ, Zambrowicz B, Olson W, Murphy AJ, Borecki IB, Shuldiner AR, Reid JG, Overton JD, Yancopoulos GD, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC, Gottesman O, Teslovich TM, Baras A, Mirshahi T, Gromada J, Dewey FE (2018) A Protein-Truncating HSD17B13 Variant and Protection from Chronic Liver Disease. N Engl J Med 378:1096–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambade A, Mandrekar P (2012) Oxidative stress and inflammation: essential partners in alcoholic liver disease. Int J Hepatol 2012:853175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson SR, Way MJ, McQuillin A, Morgan MY, Thursz MR (2017) Homozygosity for rs738409:G in PNPLA3 is associated with increased mortality following an episode of severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 67:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banini BA, Cazanave SC, Yates KP, Asgharpour A, Vincent R, Mirshahi F, Le P, Contos MJ, Tonascia J, Chalasani NP, Kowdley KV, McCullough AJ, Behling CA, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE, Sanyal AJ, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research N (2019) Haptoglobin 2 Allele is Associated With Histologic Response to Vitamin E in Subjects With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 53:750–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin JJ, Long N, Liangpunsakul S, Puri P, Kamath PS, Shah V, Sanyal AJ, Crabb DW, Chalasani NP, Urban TJ, Consortium T (2017) An exploratory genome-wide analysis of genetic risk for alcoholic hepatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 52:1263–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertaggia E, Scabia G, Dalise S, Lo Verso F, Santini F, Vitti P, Chisari C, Sandri M, Maffei M (2014) Haptoglobin is required to prevent oxidative stress and muscle atrophy. PLoS One 9:e100745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum S, Vardi M, Brown JB, Russell A, Milman U, Shapira C, Levy NS, Miller-Lotan R, Asleh R, Levy AP (2010) Vitamin E reduces cardiovascular disease in individuals with diabetes mellitus and the haptoglobin 2–2 genotype. Pharmacogenomics 11:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettger LM, Salem RM, Handsaker RE, Peloso GM, Kathiresan S, Hirschhorn JN, McCarroll SA (2016) Recurring exon deletions in the HP (haptoglobin) gene contribute to lower blood cholesterol levels. Nat Genet 48:359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch S, Stickel F, Trepo E, Way M, Herrmann A, Nischalke HD, Brosch M, Rosendahl J, Berg T, Ridinger M, Rietschel M, McQuillin A, Frank J, Kiefer F, Schreiber S, Lieb W, Soyka M, Semmo N, Aigner E, Datz C, Schmelz R, Bruckner S, Zeissig S, Stephan AM, Wodarz N, Deviere J, Clumeck N, Sarrazin C, Lammert F, Gustot T, Deltenre P, Volzke H, Lerch MM, Mayerle J, Eyer F, Schafmayer C, Cichon S, Nothen MM, Nothnagel M, Ellinghaus D, Huse K, Franke A, Zopf S, Hellerbrand C, Moreno C, Franchimont D, Morgan MY, Hampe J (2015) A genome-wide association study confirms PNPLA3 and identifies TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 as risk loci for alcohol-related cirrhosis. Nat Genet 47:1443–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhou P, De L, Li B, Su S (2019) The roles of transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 rs58542926 polymorphism in chronic liver disease: A meta-analysis of 24,147 subjects. Mol Genet Genomic Med 7:e824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, Kamath PS, Lucey M, Mathurin P, McClain C, McCullough A, Mitchell MC, Morgan TR, Nagy L, Radaeva S, Sanyal A, Shah V, Szabo G, Consortia NAH (2016) Standard Definitions and Common Data Elements for Clinical Trials in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis: Recommendation From the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology 150:785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, Mellinger JL, Lucey MR (2020) Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 71:306–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D (2009) SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Curr Protoc Hum Genet Chapter 2:Unit 2 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Bataller R (2011) Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 141:1572–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guichelaar MM, Gawrieh S, Olivier M, Viker K, Krishnan A, Sanderson S, Malinchoc M, Watt KD, Swain JM, Sarr M, Charlton MR (2013) Interactions of allelic variance of PNPLA3 with nongenetic factors in predicting nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and nonhepatic complications of severe obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21:1935–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraksingh RR, Abyzov A, Urban AE (2017) Comprehensive performance comparison of high-resolution array platforms for genome-wide Copy Number Variation (CNV) analysis in humans. BMC Genomics 18:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsley RN, Varadharajan V, Brown AL, Gromovsky AD, Schugar RC, Ramachandiran I, Fung K, Kabbany MN, Banerjee R, Neumann CK, Finney C, Pathak P, Orabi D, Osborn LJ, Massey W, Zhang R, Kadam A, Sansbury BE, Pan C, Sacks J, Lee RG, Crooke RM, Graham MJ, Lemieux ME, Gogonea V, Kirwan JP, Allende DS, Civelek M, Fox PL, Rudel LL, Lusis AJ, Spite M, Brown JM (2019) Obesity-linked suppression of membrane-bound O-acyltransferase 7 (MBOAT7) drives non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Collins SE, George WH, Wall TL, McCarthy DM, Liang T, Larimer ME (2009) Associations of ALDH2 and ADH1B genotypes with alcohol-related phenotypes in Asian young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes H, Buch S, Hutchinson S, Guha IN, Morling JR, Barnes E, Irving W, Forrest E, Pedergnana V, Goldberg D, Aspinall E, Barclay S, Hayes PC, Dillon J, Nischalke HD, Lutz P, Spengler U, Fischer J, Berg T, Brosch M, Eyer F, Datz C, Mueller S, Peccerella T, Deltenre P, Marot A, Soyka M, McQuillin A, Morgan MY, Hampe J, Stickel F (2020) Genome-Wide Association Study for Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis Identifies Risk Loci in MARC1 and HNRNPUL1. Gastroenterology 159:1276–1289 e1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois MR, Delanghe JR (1996) Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin Chem 42:1589–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liangpunsakul S, Puri P, Shah VH, Kamath P, Sanyal A, Urban T, Ren X, Katz B, Radaeva S, Chalasani N, Crabb DW, Translational R, Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment C (2016) Effects of Age, Sex, Body Weight, and Quantity of Alcohol Consumption on Occurrence and Severity of Alcoholic Hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 14:1831–1838 e1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Darvishi K, Shi X, Rajan D, Rigler D, Fitzgerald T, Lionel AC, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Macdonald JR, Mills R, Prasad A, Noonan K, Gribble S, Prigmore E, Donahoe PK, Smith RS, Park JH, Hurles ME, Carter NP, Lee C, Scherer SW, Feuk L (2011) Comprehensive assessment of array-based platforms and calling algorithms for detection of copy number variants. Nat Biotechnol 29:512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner W, Jahrbacher R, Marx-Neuhold E, Tischler S, Zulus B (2016) A novel exonuclease (TaqMan) assay for rapid haptoglobin genotyping. Clin Chem Lab Med 54:781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, Boerwinkle E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2008) Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 40:1461–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwantes-An TH, Darlay R, Mathurin P, Masson S, Liangpunsakul S, Mueller S, Aithal GP, Eyer F, Gleeson D, Thompson A, Muellhaupt B, Stickel F, Soyka M, Goldman D, Liang T, Lumeng L, Pirmohamed M, Nalpas B, Jacquet JM, Moirand R, Nahon P, Naveau S, Perney P, Botwin G, Haber PS, Seitz HK, Day CP, Foroud TM, Daly AK, Cordell HJ, Whitfield JB, Morgan TR, Seth D, Genom ALCC (2020) Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis on alcohol-related liver cirrhosis identifies novel genetic risk factors. Hepatology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozio MS, Liangpunsakul S, Crabb D (2010) The role of lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. Semin Liver Dis 30:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickel F, Lutz P, Buch S, Nischalke HD, Silva I, Rausch V, Fischer J, Weiss KH, Gotthardt D, Rosendahl J, Marot A, Elamly M, Krawczyk M, Casper M, Lammert F, Buckley TWM, McQuillin A, Spengler U, Eyer F, Vogel A, Marhenke S, von Felden J, Wege H, Sharma R, Atkinson S, Franke A, Nehring S, Moser V, Schafmayer C, Spahr L, Lackner C, Stauber RE, Canbay A, Link A, Valenti L, Grove JI, Aithal GP, Marquardt JU, Fateen W, Zopf S, Dufour JF, Trebicka J, Datz C, Deltenre P, Mueller S, Berg T, Hampe J, Morgan MY (2020) Genetic Variation in HSD17B13 Reduces the Risk of Developing Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Alcohol Misusers. Hepatology 72:88–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA (2010) Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet 42:21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CF, Lin CC, Huang HY, Liu HC, Mao SJ (2004) Antioxidant role of human haptoglobin. Proteomics 4:2221–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill L, Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V, Xuei X, Liang T, Dick DM, Kramer J, Nurnberger JI Jr., Tischfield JA, Porjesz B, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T (2008) Neuropeptide Y receptor genes are associated with alcohol dependence, alcohol withdrawal phenotypes, and cocaine dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32:2031–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuei X, Dick D, Flury-Wetherill L, Tian HJ, Agrawal A, Bierut L, Goate A, Bucholz K, Schuckit M, Nurnberger J Jr., Tischfield J, Kuperman S, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Foroud T, Edenberg HJ (2006) Association of the kappa-opioid system with alcohol dependence. Mol Psychiatry 11:1016–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima T, Kalousova M (2005) Oxidative stress and signal transduction pathways in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:110S–115S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.