Abstract

In addition to somatic mutations, germline genetic predisposition to hematologic malignancies is currently emerging as an area attracting high research interest. In this study, we investigated genetic alterations in Korean acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ALL) patients using targeted gene panel sequencing. To this end, a gene panel consisting of 81 genes that are known to be associated with 23 predisposition syndromes was investigated. In addition to sequence variants, gene-level copy number variations (CNVs) were investigated as well. We identified 197 somatic sequence variants and 223 somatic CNVs. The IKZF1 alteration was found to have an adverse effect on overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) in childhood ALL. We found recurrent somatic alterations in Korean ALL patients similar to previous studies on both prevalence and prognostic impact. Six patients were found to be carriers of variants in six genes associated with primary immunodeficiency disorder (PID). Of the 81 genes associated with 23 predisposition syndromes, this study found only one predisposition germline mutation (TP53) (1.1%). Altogether, our study demonstrated a low probability of germline mutation predisposition to ALL in Korean ALL patients.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Cancer, Genetics, Molecular biology, Biomarkers, Diseases, Molecular medicine, Oncology, Pathogenesis

Introduction

B-cell precursor and T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL, T-ALL) are two of the most common malignancies in children. ALL can be classified by genetic alterations, which are highly various and heterogeneous. Chromosome aneuploidy, structural alterations and rearrangements, copy number variations (CNVs), and sequence mutations all contribute to leukemogenesis. In 2016, the fourth edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid and myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia included new provision entities of ALL: BCR-ABL1-like (or Ph-like) ALL, iAMP21 (intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21), and early T-cell precursor ALL (ETP-ALL)1.

BCR-ABL1-like ALL is a high-risk form of ALL with its peak incidence in young adults. IKZF1 deletions, mutations of JAK-STAT and RAS signaling genes (NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, NF1, etc.), and structural rearrangements (CRLF2, ABL-class tyrosine kinase genes, JAK2, EPOR, etc.) have been identified in this group2. iAMP21 accounts for about 2% of ALL in older children, and it is associated with a number of adverse outcomes3. In iAMP21, three or more additional copies of RUNX1 (AML1) are observed on chromosome 21 in metaphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). ETP-ALL is defined as CD1a−, CD8−, CD5− (dim), and positive for one or more stem-cell or myeloid antigens. Genetic alterations in ETP are somewhat different than those in non-ETP, and FLT3, DNMT3A, and WT1 mutations are more often found in ETP than in non-ETP4, 5.

In addition to somatic mutations, germline genetic predisposition to hematologic malignancies has emerged as an area of research interest. Genes found to be associated with predisposition to myeloid malignancy have been included in the WHO classification, “Myeloid neoplasms with germ line predisposition”1; this category includes CEBPA, DDX41, RUNX1, ANKRD26, ETV6, GATA2, and others. A number of syndromes, such as bone marrow failure syndrome and telomere biology disorders, are also included in that category. One early study estimated that childhood leukemia with hereditary genetic causes accounted for 2.6% of all cancers6. Down syndrome (DS) is the most common underlying genetic predisposition for ALL6, 7. There are a number of other syndromes that also increase susceptibility to ALL, such as Li Fraumeni (TP53), Bloom syndrome (BLM), Wiskott Aldrich syndrome (WAS), ataxia telangiectasia (ATM), and Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBN)8. A germline mutation of PAX5 is highly susceptible to the development of B-ALL9.

Some genes associated with ALL are found to have both germline and somatic mutations. For example, PAX5, ETV6, TP53, and IKZF1 are known to have important somatic alterations, and germline mutations of those genes also cause susceptibility to ALL. Further, somatic and germline mutations of those genes can be found at the same time in leukemic samples9, 10. Therefore, upon initial ALL diagnosis, discrimination between somatic and germline mutations is a crucial aspect of accurately classifying ALL patient genetic subtypes/risk groups and detecting predisposition genes.

In this study, we used extensive gene panel sequencing to investigate genetic alterations (both somatic and germline) in Korean ALL patients; we also evaluated the clinical significance of recurrent somatic mutations and germline predisposition mutations in Korean ALL patients.

Results

Patients

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all 93 enrolled Korean ALL patients that are examined in this study. We enrolled 65 pediatric (< 20 years old) ALL patients and 28 adult ALL patients; this population included 12 T-ALL patients (seven children, five adults).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 93 ALL patients.

| Childhood | Adult | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 35 | 10 |

| Female | 30 | 18 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| B-ALL, NOS | 25 | 8 |

| B-ALL with t(9;22)(q34.1;q11.2); BCR-ABL1 | 2 | 11 |

| B-ALL with t(v;11q23.3); KMT2A rearranged | 4 | 1 |

| B-ALL with t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1); ETV6-RUNX1 | 9 | |

| B-ALL with hyperdiploidy | 16 | 1 |

| B-ALL with t(1;19)(q23;p13.3); TCF3-PBX1 | 2 | 2 |

| T-ALL | 5 | 5 |

| Early T-cell precursor acute leukemia | 2 | |

| Cytogenetic risk group (B-ALL) | ||

| Good | 26 | 2 |

| Intermediate | 26 | 9 |

| High | 6 | 12 |

| 65 | 28 | |

(1) good risk—ETV6-RUNX1 and high hyperdiploidy (51–65 chromosomes); (2) intermediate risk—TCF3-PBX1, IGH translocations, B-other (none of these established abnormalities); (3) high risk—BCR-ABL1, KMT2A translocations, near haploidy (30–39 chromosomes), low hypodiploidy (less than 30 chromosomes), iAMP21, TCF3-HLF.

B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 was the most common form of adult B-ALL (11/23). B-ALL, hyperdiploidy and B-ALL, and NOS were the most common forms of childhood B-ALL (41/58). B-ALL with t(12;21)(p13.2;q22.1); ETV6-RUNX1 and B-ALL with t(v;11q23.3); KMT2A rearrangement respectively occurred in nine patients and four patients. The immunophenotyping results indicate that two adults with T-ALL were diagnosed with early T-cell precursor acute leukemia.

B-ALL was divided into three risk groups based on the classifications presented in a previous study11: (1) Good risk; ETV6-RUNX1 and high hyperdiploidy (51–65 chromosomes); (2) Intermediate risk; TCF3-PBX1, IGH translocations and B-other (none of these established abnormalities); and (3) High risk; BCR-ABL1, KMT2A translocations, near haploidy (30–39 chromosomes), low hypodiploidy (less than 30 chromosomes), iAMP21, and TCF3-HLF.

Germline sequence variants among 23 syndrome-associated genes

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants

Only one TP53 variant was identified (Table 2). The TP53 NM_000546.5: c.733G > A variant was identified in a B-ALL, NOS patient. The TP53 NM_000546.5: c.733G > A variant has previously been reported in Li-Fraumeni syndrome patients (multiple cancers, including breast cancer, liver cancer, and lung cancer)12.

Table 2.

Germline pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants identified in Korean ALL patients.

| Patients | Sex/age | Diagnosis | Gene | Accession | Nucleotide | Amino acid | %Variant | dbSNP | Syndrome | Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL0009 | Female/51 | B-ALL, NOS | TP53 | NM_000546.5 | c.733G > A | p.Gly245Ser | 40.3 | rs28934575 | Li-Fraumeni syndrome | Autosomal dominant |

| ALL0067 | Male/18 | B-ALL, NOS | CASP10* | NM_032977.3 | – | – | – | – | Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, type II | Autosomal dominant |

*Exonic deletion, exon 6-exon 9.

Germline copy number variants

Only one patient (male, 18 years old, B-ALL-NOS) had a known CNV, CASP10 (deletion of exon 6-exon 9 which contained the CASc domain, as shown in Supplemental Fig. S1, Table 2). This same CNV was previously found in a patient with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis with incomplete penetrance13. CASP10 is a causative gene for autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) type IIa, and its mutation hot spot is the protease domain (CASc) with missense mutation. However, our patient with the CASP10 CNV has no clinical symptoms consistent with ALPS.

PID-associated germline sequence variants

Five PID-associated gene variants were identified in five patients (Supplement Table S1). All these variants were heterozygous autosomal recessive (AR) PID associated variants. Three variants (IL12RB1, CTC1, and LPIN2) have yet to be published, while the other variants (TYK2 and LIG4) were known variants.

Overall somatic alteration of B-ALL and T-ALL

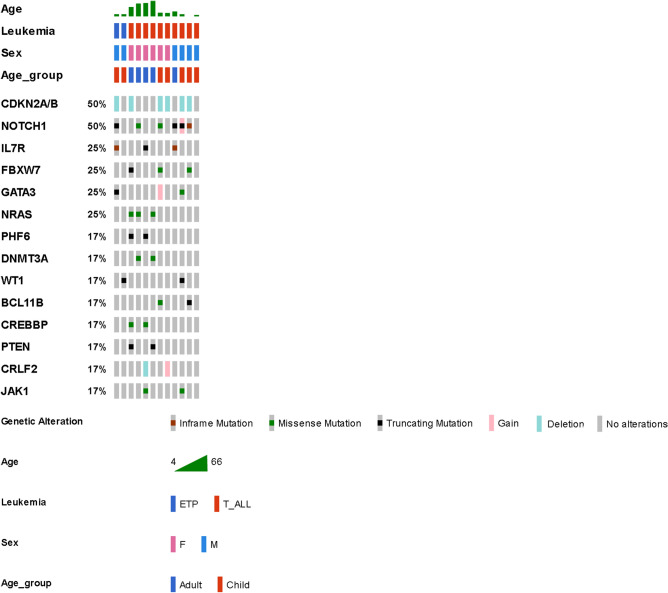

The most common genetic alterations are shown in Fig. 1 (T-ALL) and Fig. 2 (B-ALL). The most common genetic alterations of T-ALL were NOTCH1 (50%), CDKN2A/B (50%), IL7R (25%), FBXW7 (25%), GATA3 (25%), and NRAS (25%). The most common genetic lesions in T-ALL were NOTCH (58%), Chromatin structure modifiers and epigenetic regulators (58%), and the cell cycle/p53 signaling pathway (58%) (Supplement Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

Most common genetic alterations in T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL) and ETP (Early T-cell Precursor Acute Leukemia). Only ≥ two patients with gene-alterations are shown in the figure. Data were analyzed by OncoPrinter (cBioPortal Version 1.14.0, Gao et al., Sci. Signal. 2013 and Cerami et al., Cancer Discov. 2012). Truncating mutations (nonsense, frameshift deletion, frameshift insertion, splice site); inframe (inframe deletion, inframe insertion).

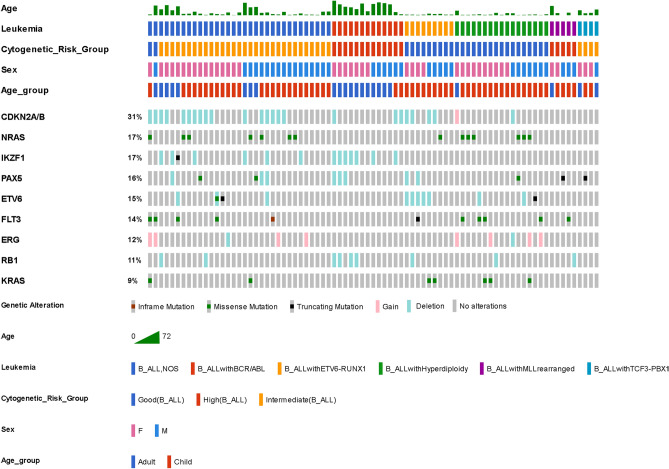

Figure 2.

Most common genetic alterations in B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL). Only ≥ seven patients with gene-alterations are shown in the figure. Data were analyzed by OncoPrinter (cBioPortal Version 1.14.0, Gao et al., Sci. Signal. 2013 and Cerami et al., Cancer Discov. 2012). Truncating mutations (nonsense, frameshift deletion, frameshift insertion, splice site); inframe (inframe deletion, inframe insertion).

The most common (> 10%) genetic alterations of B-ALL were CDKN2A/B (31%), NRAS (17%), IKZF1 (17%), PAX5 (16%), ETV6 (15%), FLT3 (14%), ERG (12%), and RB1 (11%). The most common genetic lesions in B-ALL were symphoid development and differentiation (49%), the cell cycle/p53 signaling pathway (42%), and the RAS pathway (36%) (Supplement Fig. S3).

Somatic sequence variants

We identified 197 variants after excluding synonymous variants (Supplement Table S2). NOTCH1 (50%), FBXW7 (25%), IL7R (25%), NRAS (25%), DNMT3A (17%), PHF6 (17%), and GATA3 (17%) were the most common sequence variants in B-ALL (Supplement Fig. S5). Meanwhile, NRAS (17%), FLT3 (14%), KRAS (9%), SETD2 (7%), PAX5 (6%), and CREBBP (6%) were the most common sequence variants in B-ALL (Supplement Fig. S5).

Lollipop plots of the variants are shown in Supplemental Fig. S6. All NRAS variants were previously reported variants (COSMIC database, Supplement Table S2) or the same codon variant (p.Gly12Asp/Ser, p.Gly13Asp/Val, p.Gln61Arg/Lys). All KRAS variants were also previously reported variants or the same codon variant (p.Gly12Asp/Ser, p.Gly13Asp, p.Leu23Arg, p.Ala146Val/Thr). Most of the FLT3 variants were known variants (previously found in hematologic malignancies, p.Asp835Asn/Tyr, p.Leu576Gln, p.Asn676Lys, et al.). About 50% of the PAX5 variants were also recurrent variants (p.Val26Gly, p.Ala322ArgfsTer19, p.Val26Gly).

Five of the nine NOTCH1 variants were known variants that had been found in hematologic malignancies (p.Arg1598Pro, p.Gln2503Ter, p.Glu2460Ter, p.Leu1585Gln, p.Phe1592Ser). Three of the four FBXW7 variants were known variants that were found in hematologic malignancies (p.Arg465His, p.Arg479Gln, p.Arg465His). Most of SETD2 were novel variants with no obvious hot spot mutations (seven of the eleven variants were frameshift or non-sense), as in the previous study14. The CREBBP variants were commonly found (4/8) in the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain with missense mutations, consistent with the results of a previous study15. Most of the PTPN11variants (4/5) were found in the Src homology 2 domain (SH2 domain, N-SH2 and C-SH), which are predominant region of mutation in hematologic diseases16.

Somatic copy number variants

We found a total of 223 somatic CNV. CDKN2A/B (50%), CRLF2 (17%), GATA3 (8%), CSF2RA (8%), and BCOR (8%) were the most common CNV in T-ALL (Supplement Fig. S7). CDKN2A/B (31%), IKZF1 (16%), ETV6 (12%), ERG (12%), and RB1 (11%) were the most common CNV in B-ALL (Supplement Fig. S8).

Fifteen B-ALL patients had an IKZF1 alteration (Table 3). Seven patients had B-ALL with t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); BCR-ABL1. Six B-ALL, NOS patients had an IKZF1 gene deletion. Seven of thirteen B-ALL with t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); BCR-ABL1 patients had an IKZF1 deletion (54%). Three of thirteen B-ALL with t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); BCR-ABL1 patients had a PAX5 deletion (23%).

Table 3.

IKZF1 alteration cases.

| Patients | Sex | Age group | Diagnosis | Bone marrow transplant | IKZF1 | PAX5 | Relapse | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL0003 | Female | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | – | Deletion | Deletion | – | – |

| ALL0004 | Female | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | – | Deletion | Deletion | – | Expired |

| ALL0010 | Female | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | Allogenic | Deletion | – | – | – |

| ALL0011 | Male | Adult | B-ALL, NOS | – | Deletion | – | Yes | Expired |

| ALL0024 | Female | Child | B-ALL, NOS | – | Deletion | – | Yes | – |

| ALL0026 | Male | Child | B-ALL, NOS | Allogenic | Deletion | – | Yes | Expired |

| ALL0028 | Female | Adult | B-ALL, NOS | Allogenic | Deletion | – | Yes | Expired |

| ALL0047 | Male | Child | Early T-cell precursor acute leukemia | Allogenic | Missense mutation | – | Yes | Expired |

| ALL0049 | Female | Adult | B-ALL, NOS | Allogenic | Deletion | Deletion | – | – |

| ALL0051 | Male | Child | B-ALL, NOS | – | Deletion | Deletion | – | – |

| ALL0062 | Male | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | – | Deletion | – | – | – |

| ALL0064 | Female | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | Allogenic | Deletion | – | – | – |

| ALL0065 | Female | Adult | B-ALL, NOS | Allogenic | Frameshift mutation | – | – | – |

| ALL0069 | Male | Child | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | Allogenic | Deletion | – | – | – |

| ALL0083 | Female | Adult | B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 | – | Deletion | Deletion | – | – |

CDKN2A/B by NGS and FISH

FISH for CDKN2A/B was performed upon the initial diagnosis of ALL. We compared the CDKN2A/B results between the FISH and NGS CNVs analyses. The overall agreement rate for CDKN2A/B was 83.7% (Table 4). Nine cases were positive for CDKN2A/B deletion according to NGS, but negative by FISH. Meanwhile, six cases were normal by NGS analysis, but deletion/duplication was confirmed by FISH.

Table 4.

Comparison of FISH and NGS results for CDKN2A/B deletion/duplication.

| NGS (next generation sequencing) results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion | Duplication | Normal | Total | |

| FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) results | ||||

| Deletion | 20 | 1 | 21 | |

| Duplication | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| Normal | 9 | 56 | 65 | |

| Not tested | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 30 | 1 | 62 | 93 |

Agreement rate: 83.7%.

Clinical effects of genetic alteration

Overall survival and relapse-free survival

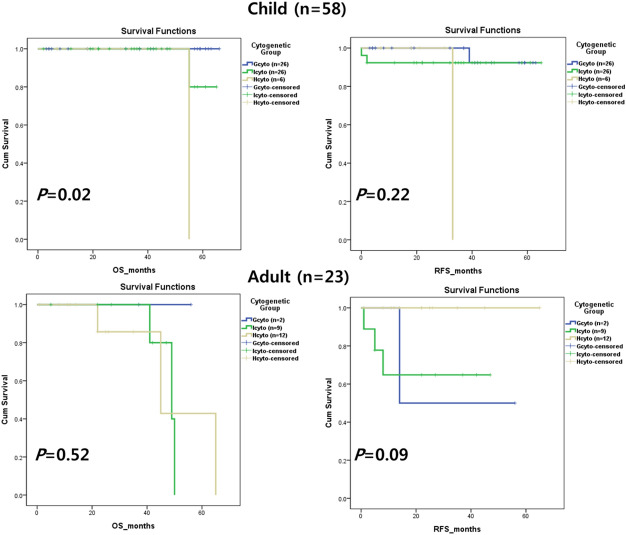

Overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) are shown by cytogenetic groups in Fig. 3. There were statistically significant differences in OS and RFS in childhood ALL, but not in adult ALL.

Figure 3.

Clinical outcomes by cytogenetic group. Overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) were both found to be statistically significant (P < 0.5) in child B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL). RFS was statistically significant in adult B-ALL. Child B-ALL were classified into good cytogenetic (Gcyto, n = 26), intermediate cytogenetic (Icyto, n = 26), and high cytogenetic risk (Hcyto, n = 6) groups. Adult B-ALL were classified into Gcyto (n = 2), Icyto (n = 9), and Hcyto (n = 12) groups.

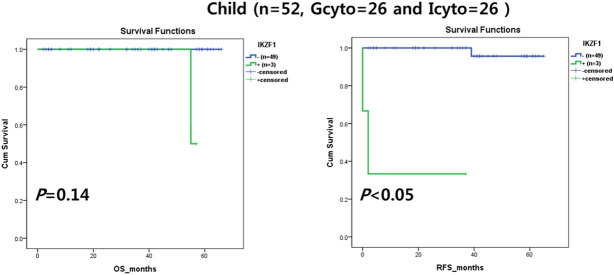

Clinical impact of IKZF1

IKZF1 alteration had adverse effects on OS and RFS only in childhood ALL (Fig. 4). No other genes had a consistent clinical effect in childhood or adult ALL (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Clinical outcomes by IKZF1 alteration. IKZF1 alteration had a prognostic impact on overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) in child B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL), particularly in the good cytogenetic (Gcyto) and intermediate cytogenetic risk (Icyto) groups. Child B-ALL were classified into Gcyto (n = 26) and Icyto (n = 26) groups.

Discussion

NGS technology has been applied to a number of hematologic diseases. Many gene panels and several methods have been used to detect not only sequence variants, but also large gene deletions and duplications or gene fusions15–19. In this study, we found a significant agreement rate between NGS and FISH for CDKN2A/B CNV detection. We also found significant IKZF1 deletions using an NGS CNV analysis. A presumed diagnosis of BCR-ABL1-like ALL can be enabled using an NGS CNV analysis to test for genetic alterations in IKZF1 and JAK1/JAK2 because the former (68%) and latter (55% among patients with CRFL2 rearrangement) are more prevalent in BCR-ABL1-like ALL than in other B-ALL sub-types2. Although we did not perform gene expression profiling and FISH, or RT-PCR for alterations commonly found in BCR-ABL1-like ALL, we found seven cases with IKZF1 alterations in non-ALL with BCR-ABL, and these showed adverse clinical effects. We assume that the seven non-ALL patients with BCR-ABL1 and an IKZF1 alteration are likely BCR-ABL1-like ALL.

In B-ALL, the most common pathogenic pathways are RAS signaling (~ 48%, NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, FLT3, NF1, etc.) and Lymphoid development/differentiation (18–80%, PAX5, IKZF1, EBF1, etc.)2, 20, 21, and we found a similar distribution of genetic changes in this study (42% RAS signaling and 49% Lymphoid development/differentiation variants were identified). The deletion of IKZF1 (~ 41.4%), CDKN2A/B (~ 36.9%), and PAX5 (~ 25.5%) are most common in overall B-ALL21, 22. IKZF1 deletion has a poor prognostic effect and is more frequent (60–90%) in B-ALL with BCR-ABL1 or high risk non-BCR-ABL1 ALL (~ 30%) than other B-ALL subtype, as shown in our results2, 11, 22, 23. Consistent with previous studies, our study showed that IKZF1 deletion was more frequent in the adult high-risk cytogenetic group (6/12, 50%) than in the overall B-ALL group (13/81, 16%). This high prevalence of IKZF1 deletion in the adult high-risk cytogenetic group might have occurred because most cases (11/12) were ALL with BCR-ABL1.

In T-ALL, we found recurrent somatic sequence variants and CNVs similar to those reported in previous studies4, 5. The sequence variants of NOTCH1 (~ 50%), PHF6 (~ 20%), JAK3-IL7R (~ 30%), and FBXW7 (~ 18%) are common mutations in T-ALL4, 5, 22–24. CDKN2A/B deletion (50%, 6/12) is most common, as shown in previous studies (50–70%)22, 23. Although only two cases of ETP were enrolled in this study, the identified variants were among the recurrent genes in T-ALL or ETP (FLT3, WT1, NOTCH1, and IL7R)4, 5. There is a need for more ETP cases to reveal the genetic alterations in T-ALL among Koreans.

Skin fibroblasts are the only recommended control sample for germline mutations, because peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow can be contaminated with leukemic cells, while other samples, such as saliva or buccal swab, can be also contaminated with PB. Further, clonal hematopoiesis can be observed in ~ 10% of the healthy population, and this rate increases with age25. However, a skin biopsy is an invasive procedure, and as a result, such samples are not readily available. We therefore used CR-state bone marrow slides (acquired to test for residual leukemic cells) as the control for germline mutations. No apparent leukemic samples were obtained in our review of bone marrow morphology, or in the FISH, chromosome, flow-cytometry, and RT-PCR results. The variant allele fraction (VAF) and public population databases were used as filtering tools26. Germline variants can have a VAF of > 33%, even in tumor samples26; variants within that range have a high possibility of germline origin. Some presumably somatic variants registered in public databases, such as the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP), the 1000 Genomes Project, the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database, and the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), may be of germline origin. We double checked the germline variants in both CR and leukemic samples. True germline variants (identified in CR samples) were also identified in paired leukemic samples with similar VAF. By contrast, true somatic variants (identified in leukemic samples) were either not found, or were found with very low VAF (< 1%) in paired CR.

Various syndromes increase the risk of ALL, with variable penetrance and preference. DS is the most common genetic cause of childhood leukemia. In an analysis of the National Registry of childhood tumors in the United Kingdom, 131 of 142 leukemia patients with underlying genetic causes were DS patients6, and an analysis of approximately 18,000 European childhood ALL cases found that 2.4% of ALL patients also had DS7. Other genetic diseases with connections to ALL include ataxia telangiectasia, Nijmegen breakage syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, familial ALL, and Noonan syndrome7. Germline PAX5 and ETV6 mutations carry a high risk (high penetrance) of cancer, mainly ALL7, 9, 27; bloom syndrome and constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome also carry a moderate risk of ALL. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome is more associated with T-cell lineage leukemia and lymphoma than B-cell lineage28. However, this study found no pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants among the gene mutations (PAX5, ETV6, NF1, BLM, ATM, etc.) that have high penetrance for ALL7. This may be because we enrolled a relatively small number of unselected sporadic cases. Moriyama et al. reported that only 0.79% (35/4,405) of sporadic childhood ALL cases have a potentially pathogenic ETV6 variant26.

In this study, we did identify only one pathogenic variant (TP53) among 81 genes associated with 23 syndromes that are well known for their connection to hematologic malignancy. For example, Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53) is a well-known rare cancer syndrome. The most common cancers in patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome are solid cancers (such as breast cancer, lung cancer, and bladder cancer)12. However, a somatic TP53 alteration is strongly associated with low hypodiploidy ALL (~ 90%), disease relapse, and germline origin (~ 40%)29. Although hypodiploid ALL accounts for only 5% of childhood ALL cases, hypodiploid ALL patients should be tested for Li-Fraumeni syndrome because of its poor prognosis and the possibility of a germline TP53 mutation30.

We found germline copy number variation in CASP10. CASP10 is a causative gene for autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) type IIa, which is a very rare PID (primary immunodeficiency disorder). However, the association between exonic deletion of CASP10 and leukemia in our patient is unclear in this study. In a previous study, similar exonic deletion of CASP10 had only been found in a patient with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis with incomplete penetrance (healthy relative with the same CNV)13. In this case, we could not find any medical history associated with ALPS in our patient.

More than 300 distinct disorders and genes of PID have been classified by the International Union of Immunological Societies PID expert committee31. An increase in leukemia/lymphoma with PID (including ALPS) is well known and expected32. Although the mechanism of leukemogenesis in PID remains unclear, intrinsic (cancer predisposition parallel to the immunological defect) and extrinsic (chronic infections, inflammation, or loss of immunosurveillance) mechanisms have been proposed by Hauck et al.33. Notably, in this study, we identified five PID-associated sequence variants and one CNV. All these sequence variants were heterozygous autosomal recessive PID associated variants. Therefore, the association between these variants and leukemia in our patients is unclear. However, some studies have reported an increased risk of cancer in heterozygous carriers of autosomal recessive PID associated variants, heterozygous BLM (Bloom syndrome, AR) mutations, and heterozygous ATM (Ataxia-telangiectasia, AR) mutations34, 35. Moreover, Qin, N. et al. have reported a risk of subsequent cancer among long-term survivors of childhood cancer with germline pathogenic/likely pathogenic mutations (DNA repairs genes which are mostly included in PID-associated genes, such as BLM, FANCA, BRCA2 LIG4, NBN, etc.)36. Therefore, further studies should continue elucidating these uncertain significant variants of PID-associated variants.

Our study had several limitations. First, we enrolled a relatively small number of cases. Second, we did not use skin fibroblasts in our search for germline mutations. Third, we did not perform a familial study or any clinical or physical investigations of the identified germline variants.

Conclusion

We found recurrent somatic alterations in Korean ALL patients. Further, we identified the low probability of germline mutation predisposition in unselected sporadic Korean ALL patients. We also demonstrated the usefulness of NGS technology, which provides comprehensive genetic information.

Methods

Study population and samples

We selected paired initial-diagnosis and complete remission (CR) bone marrow samples from patients diagnosed with ALL at Samsung Medical Center from 2008 to 2012.

The Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center approved this study (IRB No. 2015-11-053), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

To detect germline mutations, we used bone marrow slides that were obtained when the patients were in CR. In total, 31 (33.3%) patients received allogenic stem cell transplantation. CR status bone marrow slides before allogenic stem cell transplantation were used to accurately detect patient germline mutations. The morphology, chromosome, FISH, and immunophenotyping results were reviewed, and bone marrow slides with no apparent residual leukemic cells were selected as control samples.

Conventional study

A chromosome study was conducted using a standard method, and the karyotypes are described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed to detect recurrent translocation (HemaVision kit, DNA Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). FLT-ITD mutation analyses (by fragment length polymorphism) and FISH for CDKN2A/B were performed as well.

Targeted gene sequencing

Gene panel

From a literature review, we selected 500 genes found to be significantly mutated in ALL (Supplement Table S5). Our gene panel17 included the following: cell cycle and p53 signaling pathway (ATM, CDKN1B, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, RB, TP53, etc.), chromatin structure modifiers and epigenetic regulators (ARID1A, BMI1, CHD1, CHD4, CHD9, CREBBP, CTCF, DNMT3A, EED, EP300, EZH2, KDM5C, KDM6A, KMT2A, KMT2C, KMT2D, NR3C1, PHF6, SETD2, SUZ12, WHSC1, etc.), JAK-STAT signaling pathway (CRLF2, IL2RB, IL7R, JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, PTPN2, SH2B3, STAT3, TYK2, etc.), DNA repair (MSH2, MSH6, ZFHX4, etc.), NOTCH pathway (FBXW7, NOTCH1, etc.), PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway (AKT2, PIK3CD, PIK3R1, PTEN, etc.), RAS pathway (BRAF, CBL, FLT3, KRAS, NF1, NRAS, PTPN11, etc.), and transcriptional processes (BCL11B, DNM2, ERG, GATA3, LMO2, MYB, RELN, TAL1, TBL1XR1, TLX1, TLX3, WT1, etc.).

Predisposition syndrome to hematologic malignancies

We included 23 well known predisposition syndromes (81 genes) in our next generation sequencing (NGS) panel: ataxia pancytopenia syndrome (SAMD9L), ataxia telangiectasia (ATM), Bloom syndrome (BLM), constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM), Diamond-Blackfan anemia (GATA1, RPL5, RPL11, RPL15, RPL23, RPL26, RPL27, RPL31, RPL35a, RPL36, RPS7, RPS10, RPS15, RPS17, RPS19,RPS24, RPS26, RPS27, RPS27A, RPS28, RPS29, and TSR2), dyskeratosis congenita (DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOP10, NHP2, TINF2, WRAP53, CTC1, RTEL1, ACD, PARN, and NAF1), familial acute myeloid leukemia (CEBPa), familial platelet disorder with propensity to myeloid malignancy (RUNX1), Fanconi anemia (FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, BRCA2, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCI, BRIP1, FANCL, FANCM, PALB2, RAD51C, SLX4, ERCC4, RAD51, BRCA1,UBE2T, XRCC2, and MAD2L2), GATA2-spectrum disorders (GATA2), Li Fraumeni (TP53), Ligase IV syndrome (LIG4), neurofibromatosis (NF1and SRP72), Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBN), Noonan syndrome (PTPN11), Noonan-like syndrome (CBL), severe congenital neutropenia 3 (DDX41 and HAX1), severe congenital neutropenia (ELANE), Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SBDS), susceptibility to ALL 3 (PAX5), thrombocytopenia 2 (ANKRD26), thrombocytopenia 5 (ETV6), and Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome (WAS).

Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted using previously described methods (Supplement Fig. S9)17. After sequencing, we aligned the reads to human genomic reference sequences (GRCh37) using the Burrows–Wheeler alignment tool. The Genome Analysis Tool Kit (Broad Institute) was used for variant calling. Pindel was used for crosscheck insertion and mutation deletion. All mutations were annotated using ANNOVAR and VEP software. Variants were further examined by visual inspection using the Integrative Genomic Viewer. Annotated variants were classified using automated algorithm software, DxSeq Analyzer (Dxome, Seoul, Korea), by applying the standards and guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology37. ExomeDepth (1.1.10), an R package, was used to detect exon- and gene-level CNVs in target regions, followed by visualization using a base-level read depth normalization algorithm implemented in a DxSeq Analyzer (Dxome, Seoul, Korea)17. To obtain reliable results, we used cutoff values for the average depth and % covered (30×) of 700× and 99%, respectively. The minimal reportable VAF was ≥ 1%.

Statistical analysis

Differences in survival according to mutation group were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier estimates. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed in PASW Statistics 20.0.

Ethics declarations

The Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center approved this study (IRB No. 2015-11-053), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Grant (NRF-2017R1D1A1B04028149) provided by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Republic of Korea.

Author contributions

S.Y., S.H. and S.T. designed the experiments; S.Y. and H.H. analyzed and interpreted the data; J.R., C.W., H.H., and S.H. supervised and coordinated the experiment; and S.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Seung-Tae Lee, Email: LEE.ST@yuhs.ac.

Sun-Hee Kim, Email: drsunnyhk@gmail.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-88449-4.

References

- 1.Arber DA, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts KG, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison CJ, et al. An international study of intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 (iAMP21): Cytogenetic characterization and outcome. Leukemia. 2014;28:1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain N, et al. Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ETP-ALL/LBL) in adolescents and adults: A high-risk subtype. Blood. 2016;127:1863–1869. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-661702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narod SA, Stiller C, Lenoir GM. An estimate of the heritable fraction of childhood cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1991;63:993–999. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kratz CP, Stanulla M, Cave H. Genetic predisposition to acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Overview on behalf of the I-BFM ALL Host Genetic Variation Working Group. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2016;59:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furutani E, Shimamura A. Germline genetic predisposition to hematologic malignancy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:1018–1028. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.8644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah S, et al. A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1226–1231. doi: 10.1038/ng.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feurstein S, Drazer MW, Godley LA. Genetic predisposition to leukemia and other hematologic malignancies. Semin. Oncol. 2016;43:598–608. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moorman AV. New and emerging prognostic and predictive genetic biomarkers in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101:407–416. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruijs MW, et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: Mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:421–428. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tadaki H, et al. Exonic deletion of CASP10 in a patient presenting with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but not with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type IIa. Int. J. Immunogenet. 2011;38:287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2011.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mar BG, et al. Mutations in epigenetic regulators including SETD2 are gained during relapse in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3469. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullighan CG, et al. CREBBP mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;471:235–239. doi: 10.1038/nature09727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentires-Alj M, et al. Activating mutations of the noonan syndrome-associated SHP2/PTPN11 gene in human solid tumors and adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Can. Res. 2004;64:8816–8820. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim B, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing can serve as an alternative to conventional tests in myeloid neoplasms. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0212228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim B, Kim S, Lee ST, Min YH, Choi JR. FLT3 Internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia is readily detectable in a single next-generation sequencing assay using the pindel algorithm. Ann. Lab. Med. 2019;39:327–329. doi: 10.3343/alm.2019.39.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy MA, et al. Implementation of an NGS-based sequencing and gene fusion panel for clinical screening of patients with suspected hematologic malignancies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019;103:178–189. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montano A, Forero-Castro M, Marchena-Mendoza D, Benito R, Hernandez-Rivas JM. New challenges in targeting signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia by NGS approaches: An update. Cancers. 2018 doi: 10.3390/cancers10040110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messina M, et al. Clinical significance of recurrent copy number aberrations in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia without recurrent fusion genes across age cohorts. Br. J. Haematol. 2017;178:583–587. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakral D, et al. Rapid identification of key copy number alterations in B- and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia by digital multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:871. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang Q, et al. Prognostic significance of copy number alterations detected by multi-link probe amplification of multiple genes in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:5359–5367. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vicente C, et al. Targeted sequencing identifies associations between IL7R-JAK mutations and epigenetic modulators in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100:1301–1310. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.130179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaiswal S, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yannakou CK, et al. Incidental detection of germline variants of potential clinical significance by massively parallel sequencing in haematological malignancies. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018;71:84–87. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriyama T, et al. Germline genetic variation in ETV6 and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A systematic genetic study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1659–1666. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ripperger T, Schlegelberger B. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma in the context of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2016;59:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmfeldt L, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:242–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian M, et al. TP53 Germline variations influence the predisposition and prognosis of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:591–599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bousfiha A, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2019 update of the IUIS phenotypical classification. J. Clin. Immunol. 2020;40:66–81. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00758-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayor PC, et al. Cancer in primary immunodeficiency diseases: Cancer incidence in the United States Immune Deficiency Network Registry. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;141:1028–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauck F, Voss R, Urban C, Seidel MG. Intrinsic and extrinsic causes of malignancies in patients with primary immunodeficiency disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;141:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Voer RM, et al. Deleterious germline BLM mutations and the risk for early-onset colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep14060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stankovic T, et al. ATM mutation in sporadic lymphoid tumors. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2002;43:1563–1571. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000002884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin N, et al. Pathogenic germline mutations in DNA repair genes in combination with cancer treatment exposures and risk of subsequent neoplasms among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:2728–2740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.